Totem pole

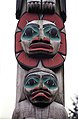

Totem poles (Haida: gyáaʼaang)[1] are monumental carvings found in western Canada and the northwestern United States. They are a type of Northwest Coast art, consisting of poles, posts or pillars, carved with symbols or figures. They are usually made from large trees, mostly western red cedar, by First Nations and Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast including northern Northwest Coast Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian communities in Southeast Alaska and British Columbia, Kwakwaka'wakw and Nuu-chah-nulth communities in southern British Columbia, and the Coast Salish communities in Washington and British Columbia.[1]

The word totem derives from the Algonquian word odoodem [oˈtuːtɛm] meaning "(his) kinship group". The carvings may symbolize or commemorate ancestors, cultural beliefs that recount familiar legends, clan lineages, or notable events. The poles may also serve as functional architectural features, welcome signs for village visitors, mortuary vessels for the remains of deceased ancestors, or as a means to publicly ridicule someone. They may embody a historical narrative of significance to the people carving and installing the pole. Given the complexity and symbolic meanings of these various carvings, their placement and importance lies in the observer's knowledge and connection to the meanings of the figures and the culture in which they are embedded. Contrary to common misconception, they are not worshipped or the subject of spiritual practice.[2][3][4]

History

Totem poles serve as important illustrations of family lineage and the cultural heritage of the Indigenous peoples in the islands and coastal areas of North America's Pacific Northwest, especially British Columbia, Canada, and coastal areas of Washington and southeastern Alaska in the United States. Families of traditional carvers come from the Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl), Nuxalk (Bella Coola), and Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), among others.[5][6] The poles are typically carved from the highly rot-resistant trunks of Thuja plicata trees (popularly known as giant cedar or western red cedar), which eventually decay in the moist, rainy climate of the coastal Pacific Northwest. Because of the region's climate and the nature of the materials used to make the poles, few examples carved before 1900 remain. Noteworthy examples, some dating as far back as 1880, include those at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, the Museum of Anthropology at UBC in Vancouver, the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, and the Totem Heritage Center in Ketchikan, Alaska.

Totem poles are the largest, but not the only, objects that coastal Pacific Northwest natives use to depict spiritual reverence, family legends, sacred beings and culturally important animals, people, or historical events. The freestanding poles seen by the region's first European explorers were likely preceded by a long history of decorative carving. Stylistic features of these poles were borrowed from earlier, smaller prototypes, or from the interior support posts of house beams.[7][8]

Although 18th-century accounts of European explorers traveling along the coast indicate that decorated interior and exterior house posts existed prior to 1800, the posts were smaller and fewer in number than in subsequent decades. Prior to the 19th century, the lack of efficient carving tools, along with sufficient wealth and leisure time to devote to the craft, delayed the development of elaborately carved, freestanding poles.[9] Before iron and steel arrived in the area, artists used tools made of stone, shells, or beaver teeth for carving. The process was slow and laborious; axes were unknown. By the late eighteenth century, the use of metal cutting tools enabled more complex carvings and increased production of totem poles.[7] The tall monumental poles appearing in front of homes in coastal villages probably did not appear until after the beginning of the nineteenth century.[9]

Eddie Malin has proposed that totem poles progressed from house posts, funerary containers, and memorial markers into symbols of clan and family wealth and prestige. He argues that the Haida people of the islands of Haida Gwaii originated carving of the poles, and that the practice spread outward to the Tsimshian and Tlingit, and then down the coast to the Indigenous people of British Columbia and northern Washington.[10] Malin's theory is supported by the photographic documentation of the Pacific Northwest coast's cultural history and the more sophisticated designs of the Haida poles.

Accounts from the 1700s describe and illustrate carved poles and timber homes along the coast of the Pacific Northwest.[11][12] By the early nineteenth century, widespread importation of iron and steel tools from Great Britain, the United States, and elsewhere led to easier and more rapid production of carved wooden goods, including poles.[13]

In the 19th century, American and European trade and settlement initially led to the growth of totem-pole carving, but United States and Canadian policies and practices of acculturation and assimilation caused a decline in the development of Alaska Native and First Nations cultures and their crafts, and sharply reduced totem-pole production by the end of the century. Between 1830 and 1880, the maritime fur trade, mining, and fisheries gave rise to an accumulation of wealth among the coastal peoples.[14][15] Much of it was spent and distributed in lavish potlatch celebrations, frequently associated with the construction and erection of totem poles.[16] The monumental poles commissioned by wealthy family leaders to represent their social status and the importance of their families and clans.[17] In the 1880s and 1890s, tourists, collectors, scientists and naturalist interested in Indigenous culture collected and photographed totem poles and other artifacts, many of which were put on display at expositions such as the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the 1893 World's Columbia Exposition in Chicago, Illinois.[18]

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, before the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978, the practice of Indigenous religion was outlawed, and traditional Indigenous cultural practices were also strongly discouraged by Christian missionaries. This included the carving of totem poles. Missionaries urged converts to cease production and destroy existing poles. Nearly all totem-pole-making had ceased by 1901.[19] Carving of monumental and mortuary poles continued in some, more remote villages as late as 1905; however, as the original sites were abandoned, the poles and timber homes were left to decay and vandalism.[20]

Beginning in the late 1930s, a combination of cultural, linguistic, and artistic revivals, along with scholarly interest and the continuing fascination and support of an educated and empathetic public, led to a renewal and extension of this artistic tradition.[18] In 1938 the United States Forest Service began a program to reconstruct and preserve the old poles, salvaging about 200, roughly one-third of those known to be standing at the end of the 19th century.[20] With renewed interest in Indigenous arts and traditions in the 1960s and 1970s, freshly carved totem poles were erected up and down the coast, while related artistic production was introduced in many new and traditional media, ranging from tourist trinkets to masterful works in wood, stone, blown and etched glass, and other traditional and non-traditional media.[18]

In June 2022 during the biennial Celebration festival in Juneau, Alaska, the Sealaska Heritage Institute unveiled the first 360-degree totem pole in Alaska: the 6.7-metre-tall (22 ft) Sealaska Cultural Values Totem Pole.[21][22] The structure, carved out of a 600-year-old cedar tree, "represents all three tribes of Southeast Alaska — Lingít, Haida and Tsimshian."[23]

Meaning and purpose

Totem poles can symbolize characters and events in mythology, or convey the experiences of recent ancestors and living people.[6] Some of these characters may appear as stylistic representations of objects in nature, while others are more realistically carved. Pole carvings may include animals, fish, plants, insects, and humans, or they may represent supernatural beings such as the Thunderbird. Some symbolize beings that can transform themselves into another form, appearing as combinations of animals or part-animal/part-human forms. Consistent use of a specific character over time, with some slight variations in carving style, helped develop similarities among these shared symbols that allowed people to recognize one from another. For example, the raven is symbolized by a long, straight beak, while the eagle's beak is curved, and a beaver is depicted with two large front teeth, a piece of wood held in his front paws, and a paddle-shaped tail.[24][25]

The meanings of the designs on totem poles are as varied as the cultures that make them. Some poles celebrate cultural beliefs that may recount familiar legends, clan lineages, or notable events, while others are mostly artistic. Animals and other characters carved on the pole are typically used as symbols to represent characters or events in a story; however, some may reference the moiety of the pole's owner,[26] or simply fill up empty space on the pole.[27] Depictions of thrusting tongues and linked tongues may symbolize socio-political power.[28]

The carved figures interlock one above the other to create the overall design, which may rise to a height of 60 ft (18 m) or more. Smaller carvings may be positioned in vacant spaces, or they may be tucked inside the ears or hang out of the mouths of the pole's larger figures.[29][30]

Some of the figures on the poles constitute symbolic reminders of quarrels, murders, debts, and other unpleasant occurrences about which the Native Americans prefer to remain silent... The most widely known tales, like those of the exploits of Raven and of Kats who married the bear woman, are familiar to almost every native of the area. Carvings which symbolize these tales are sufficiently conventionalized to be readily recognizable even by persons whose lineage did not recount them as their own legendary history.[31]

People from cultures that do not carve totem poles often assume that the linear representation of the figures places the most importance on the highest figure, an idea that became pervasive in the dominant culture after it entered into mainstream parlance by the 1930s with the phrase "low man on the totem pole"[32] (and as the title of a bestselling 1941 humor book by H. Allen Smith). However, Native sources either reject the linear component altogether, or reverse the hierarchy, with the most important representations on the bottom, bearing the weight of all the other figures, or at eye-level with the viewer to heighten their significance.[33] Many poles have no vertical arrangement at all, consisting of a lone figure atop an undecorated column.

Types

There are six basic types of upright, pole carvings that are commonly referred to as "totem poles"; not all involve the carving of what may be considered "totem" figures: house frontal poles, interior house posts, mortuary poles, memorial poles, welcome poles, and the ridicule or shame pole.[34]

House frontal poles

This type of pole, usually 20 to 40 ft (6 to 12 m) tall[35] is the most decorative. Its carvings tell the story of the family, clan or village who own them. These poles are also known as heraldic, crest, or family poles. Poles of this type are placed outside the clan house of the most important village leaders. Often, watchman figures are carved at the top of the pole to protect the pole owner's family and the village. Another type of house frontal pole is the entrance or doorway pole, which is attached to the center front of the home and includes an oval-shaped opening through the base that serves as the entrance to the clan house.[36]

House posts

These interior poles, typically 7 to 10 ft (2 to 3 m) in height, are usually shorter than exterior poles.[35] The interior posts support the roof beam of a clan house and include a large notch at the top, where the beam can rest.[36] A clan house may have two to four or more house posts, depending on the cultural group who built it. Carvings on these poles, like those of the house frontal poles, are often used as a storytelling device and help tell the story of the owners' family history.[37][38] House posts were carved by the Coast Salish and were more common than the free-standing totem poles seen in Northern cultural groups.[39]

Mortuary pole

The rarest type of pole carving is a mortuary structure that incorporates grave boxes with carved supporting poles. It may include a recessed back to hold the grave box. These are among the tallest and most prominent poles, reaching 50 to 70 ft (15 to 21 m) in height.[37] The Haida and Tlingit people erect mortuary poles at the death of important individuals in the community. These poles may have a single figure carved at the top, which may depict the clan's crest, but carvings usually cover its entire length. Ashes or the body of the deceased person are placed in the upper portion of the pole.[38]

Memorial pole

This type of pole, which usually stands in front of a clan house, is erected about a year after a person has died. The clan chief's memorial pole may be raised at the center of the village.[37] The pole's purpose is to honor the deceased person and identify the relative who is taking over as his successor within the clan and the community. Traditionally, the memorial pole has one carved figure at the top, but an additional figure may also be added at the bottom of the pole.[38]

Memorial poles may also commemorate an event. For example, several memorial totem poles were erected by the Tlingits in honor of Abraham Lincoln, one of which was relocated to Saxman, Alaska, in 1938.[40] The Lincoln pole at Saxman commemorates the end of hostilities between two rival Tlingit clans and symbolizes the hope for peace and prosperity following the American occupation of the Alaskan territory.[41] The story begins in 1868, when the United States government built a customs house and fort on Tongass Island and left the US revenue cutter Lincoln to patrol the area. After American soldiers at the fort and aboard the Lincoln provided protection to the Tongass group against its rival, the Kagwantans, the Tongass group commissioned the Lincoln pole to commemorate the event.[42][43]

Welcome pole

Carved by the Kwakwaka'wakw (Kwakiutl), Salish and Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people, most of the poles include large carvings of human figures, some as tall as 40 ft (12 m).[44][45] Welcome poles are placed at the edge of a stream or saltwater beach to welcome guests to the community, or possibly to intimidate strangers.[38][46][47]

Shame/ridicule pole

Poles used for public ridicule are usually called shame poles, and were created to embarrass individuals or groups for their unpaid debts or when they did something wrong.[38][48] The poles are often placed in prominent locations and removed after the debt is paid or the wrong is corrected. Shame pole carvings represent the person being shamed.[38][49]

One famous shame pole is the Seward Pole at the Saxman Totem Park in Saxman, Alaska. Originally carved in the c. 1885, the pole shamed former U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward for his "lack of recognition of Indigenous peoples at an early point in Alaska’s U.S. history," as well as not reciprocating the generosity of his Tlingit hosts following an 1869 potlatch given in his honor.[50] The figure's red-painted nose and ears may symbolize drunkenness or Seward's stinginess.[51][52] In the 1940s, a second iteration of the pole was built by Tlingit men enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps; according to the Alaska Historical Society, the United States government was unaware that the pole's intent was to shame Seward until after the completion of the project.[50] In 2014, this second pole began to fall apart; a renewed version was carved in 2017 by local Tlingit artist Stephen Jackson, who combined political caricature with Northwest Coast style.[50]

Another example of the shame pole is the Three Frogs pole on Chief Shakes Island, at Wrangell, Alaska. This pole was erected by Chief Shakes to shame the Kiks.ádi clan into repaying a debt incurred for the support of three Kiks.ádi women who were allegedly cohabiting with three slaves in Shakes's household. When the Kiks.ádi leaders refused to pay support for the women, Shakes commissioned a pole with carvings of three frogs, which represented the crest of the Kiks.ádi clan. It is not known if the debt was ever repaid.[53] The pole stands next to the Chief Shakes Tribal House in Wrangell. The pole's unique crossbar shape has become popularly associated with the town of Wrangell, and continues to be used as part of the Wrangell Sentinel newspaper's masthead.[54]

In 1942, the U.S. Forest Service commissioned a pole to commemorate Alexander Baranof, the Russian governor and Russian American Company manager, as a civilian works project. The pole's original intent was to commemorate a peace treaty between the Russians and Tlingits that the governor helped broker in 1805. George Benson, a Sitka carver and craftsman, created the original design. The completed version originally stood in Totem Square in downtown Sitka, Alaska.[55][56] When Benson and other Sitka carvers were not available to do the work, the U.S. Forest Service had CCC workers carve the pole in Wrangell, Alaska. Because Sitka and Wrangell native groups were rivals, it has been argued that the Wrangell carvers may have altered Benson's original design.[56][57] For unknown reasons, the Wrangell carvers depicted the Baranov figure without clothes.[58] Following a Sitka Tribe of Alaska-sponsored removal ceremony, the pole was lowered due to safety concerns on October 20, 2010, using funds from the Alaska Dept. of Health and Social Services. The Sitka Sentinel reported that while standing, it was "said to be the most photographed totem [pole] in Alaska".[55] The pole was re-erected in Totem Square in 2011.[59]

On March 24, 2007, a shame pole was erected in Cordova, Alaska, that includes the inverted and distorted face of former Exxon CEO Lee Raymond. The pole represents the unpaid debt of $5 billion in punitive damages that a federal court in Anchorage, Alaska, determined Exxon owes for its role in causing the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound.[60][61]

Totem poles outside of original context

Some poles from the Pacific Northwest have been moved to other locations for display out of their original context.[62]

In 1903 Alaska's district governor, John Green Brady, collected fifteen Tlingit and Haida totem poles for public displays from villages in southeastern Alaska.[63][64] At the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (the world's fair held in Saint Louis, Missouri, in 1904), fourteen of them were initially installed outside the Alaska pavilion at the fair; the other one, which had broken in transit, was repaired and installed at the fair's Esquimau Village.[65] Thirteen of these poles were returned to Alaska, where they were eventually installed in the Sitka National Historical Park. The other two poles were sold; one pole from the Alaska pavilion went to the Milwaukee Public Museum and the pole from the Esquimau Village was sold and then given to industrialist David M. Parry, who installed it on his estate in what became known as the Golden Hill neighborhood of Indianapolis, Indiana.[66] Although the remains of the original pole at Golden Hill no longer exist, a replica was raised on April 13, 1996, on the front lawn of The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis.[67] Approximately two years later, the replica was moved inside the museum, and in 2005, it was installed in a new atrium after completion of a museum expansion project.[68]

Indian New Deal

The Indian New Deal of the 1930s strongly promoted native arts and crafts in the United States, and in the totem pole they discovered an art that was widely appreciated by white society. In Alaska the Indian Division of the Civilian Conservation Corps restored old totem poles, copied those beyond repair, and carved new ones. The Indian Arts and Crafts Board, a U.S. federal government agency, facilitated their sale to the general public. The project was lucrative, but anthropologists complained that it stripped the natives of their traditional culture and stripped away the meaning of the totem poles.[69][70]

Another example occurred in 1938, when the U.S. Forest Service began a totem pole restoration program in Alaska.[71] Poles were removed from their original places as funerary and crest poles to be copied or repaired and then placed in parks based on English and French garden designs to demystify their meaning for tourists.[72]

In England at the side of Virginia Water Lake, in the south of Windsor Great Park, there is a 100-foot-tall (30 m) Canadian totem pole that was given to Queen Elizabeth II to commemorate the centenary of British Columbia. In Seattle, Washington, a Tlingit funerary totem pole was raised in Pioneer Square in 1899, after being taken from an Alaskan village.[73] In addition, the totem pole collections in Vancouver's Stanley Park, Victoria's Thunderbird Park, and the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia were removed from their original locations around British Columbia.[74] In Stanley Park, the original Skedans Mortuary Pole has been returned to Haida Gwaii and is now replaced by a replica. In the late 1980s, the remaining carved poles were sent to various museums for preservation, with the park board commissioning and loaning replacement carvings.[74][75]

Construction and maintenance

After the tree to be used for the totem pole is selected, it is cut down and moved to the carving site, where the bark and outer layer of wood (sapwood) is removed. Next, the side of the tree to be carved is chosen and the back half of the tree is removed. The center of the log is hollowed out to make it lighter and to keep it from cracking.[76] Early tools used to carve totem poles were made of stone, shell, or bone, but beginning in the late 1700s, the use of iron tools made the carving work faster and easier. In the early days, the basic design for figures may have been painted on the wood to guide the carvers, but today's carvers use paper patterns as outlines for their designs. Carvers use chain saws to make the rough shapes and cuts, while adzes and chisels are used to chop the wood. Carvers use knives and other woodworking tools to add the finer details. When the carving is complete, paint is added to enhance specific details of the figures.[76]

Raising a totem pole is rarely done using modern methods, even for poles installed in modern settings. Most artists use a traditional method followed by a pole-raising ceremony. The traditional method calls for a deep trench to be dug. One end of the pole is placed at the bottom of the trench; the other end is supported at an upward angle by a wooden scaffold. Hundreds of strong men haul the pole upright into its footing, while others steady the pole from side ropes and brace it with cross beams. Once the pole is upright, the trench is filled with rocks and dirt. After the raising is completed, the carver, the carver's assistants, and others invited to attend the event perform a celebratory dance next to the pole. A community potlatch celebration typically follows the pole raising to commemorate the event.[77]

Totem poles are typically not well maintained after their installation and the potlatch celebration. The poles usually last from 60 to 80 years; only a few have stood longer than 75 years, and even fewer have reached 100 years of age.[20] Once the wood rots so badly that the pole begins to lean and pose a threat to passersby, it is either destroyed or pushed over and removed. Older poles typically fall over during the winter storms that batter the coast. The owners of a collapsed pole may commission a new one to replace it.[24]

Cultural property

Each culture typically has complex rules and customs regarding the traditional designs represented on poles. The designs are generally considered the property of a particular clan or family group of traditional carvers, and this ownership of the designs may not be transferred to the person who has commissioned the carvings. There have been protests when those who have not been trained in the traditional carving methods, cultural meanings and protocol, have made "fake totem poles" for what could be considered crass public display and commercial purposes.[78] The misappropriation of coastal Pacific Northwest culture by the art and tourist trinket market has resulted in production of cheap imitations of totem poles executed with little or no knowledge of their complex stylistic conventions or cultural significance. These include imitations made for commercial and even comedic use in venues that serve alcohol, and in other settings that are insensitive or outright offensive to the sacred nature of some of the carvings.[78]

In the early 1990s, the Haisla First Nation of the Pacific Northwest began a lengthy struggle to repatriate the Gʼpsgolox totem pole from Sweden's Museum of Ethnography.[79][80] Their successful efforts were documented in Gil Cardinal's National Film Board of Canada documentary, Totem: The Return of the G'psgolox Pole.[81]

In October 2015, a Tlingit totem pole was returned from Hawaii to Alaska after being taken from a village by Hollywood actor John Barrymore in 1931.[82]

Gallery

-

Totem poles in front of homes in Alert Bay, British Columbia in the 1900s

-

Totem poles in Skidegate, 26 July 1878

-

A totem pole in Totem Park, Victoria, British Columbia

-

From Totem Park, Victoria, British Columbia

-

The K'alyaan Totem Pole of the Tlingit Kiks.ádi Clan, erected at Sitka National Historical Park to commemorate the lives lost in the 1804 Battle of Sitka

-

From Saxman Totem Park, Ketchikan, Alaska

-

From Saxman Totem Park, Ketchikan, Alaska

-

From Brockton Point, Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia

-

Replica of G'psgolox Pole. A gift from the Haisla First Nation to the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm, Sweden.

-

US 50th Infantry Regiment Coat of arms with a totem pole arrangement of a US American eagle and a Russian Bear (signifying transfer of ownership of Alaska from Russia to United States)

-

Kwakwaka'wakw House Post at the American Museum of Natural History

-

House post at the Museum of Anthropology at UBC

-

Haida totem pole. Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver, BC

-

Kwakwaka'wakw totem pole on Notre Dame Island in Montreal

-

Totem poles at Ye Olde Curiosity Shop

-

1928 Emily Carr painting, Kitwancool

-

Totem pole by Lelooska, Don Morse Smith (non-Native[83]) at Denver Museum of Nature and Science

-

The Kayung totem pole in 1884

-

The Kayung totem pole at the British Museum

-

Totem poles at the Canadian Museum of History

-

Totem pole at Chapultepec

Examples

The title of "The World's Tallest Totem Pole" is or has at one time been claimed by several coastal towns of North America's Pacific Northwest.[84] Disputes over which is genuinely the tallest depends on factors such the number of logs used in construction or the affiliation of the carver. Competitions to make the tallest pole remain prevalent, although it is becoming more difficult to procure trees of sufficient height. The tallest poles include those in:

- Alert Bay, British Columbia—173 feet (53 m), Kwakwaka'wakw. This pole is composed of two or three pieces.[84]

- McKinleyville, California—160 feet (49 m), carved from a single redwood tree by Ernest Pierson and John Nelson.

- Kalama, Washington—149 feet (45 m), carved from a single pole by Lelooska.[84]

- Kake, Alaska—132 feet (40 m), single log carving,[84] Tlingit

- Victoria, British Columbia (Beacon Hill Park)—127.7 feet (38.9 m), raised in 1956,[84] Kwakwaka'wakw, carved by Mungo Martin with Henry Hunt and David Martin.

- Tacoma, Washington (Fireman's Park)—105 feet (32 m), carved by Alaska Natives in 1903.[84]

- Vancouver, British Columbia (Maritime Museum) —100 feet (30 m), Kwakwaka'wakw, carved by Mungo Martin with Henry Hunt and David Martin.

The thickest totem pole ever carved to date is in Duncan, British Columbia. Carved by Richard Hunt in 1988 in the Kwakwaka'wakw style, and measuring over 6 feet (1.8 m) in diameter, it represents Cedar Man transforming into his human form.[85]

Notable collections of totem poles on display include these sites:

- Alaska State Museum, Juneau, Alaska[86]

- American Museum of Natural History, New York City, New York

- Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Seattle[87]

- Canadian Museum of History, Hull area of Gatineau, Quebec

- Duncan, British Columbia, the City of Totems

- Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site, Haida Gwaii, British Columbia

- Haida Heritage Centre, Skidegate, British Columbia

- 'Ksan, near Hazelton, British Columbia

- Museum of Anthropology at UBC, Vancouver, British Columbia

- Nisga'a and Haida Crest Poles of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto

- Nisga'a Museum, in Laxgalts'ap, British Columbia

- Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, British Columbia

- Saxman Totem Park, Saxman, Alaska[88]

- Sitka National Historical Park, Sitka, Alaska[89]

- Stanley Park (Brockton Point), Vancouver, British Columbia

- Totem Bight State Historical Park, Ketchikan, Alaska

- Thunderbird Park, Victoria, British Columbia[90]

- Totem Heritage Center, Ketchikan, Alaska[91]

See also

- Huabiao

- Jangseung

- Crest (heraldry)

- Stele

- Roofed pole

- Irminsul

- Tiki

- Chemamull

- Serge (religious)

- Conservation and restoration of totem poles

Notes

- ^ a b Wright, Robin K. (n.d.). "Totem Poles: Heraldic Columns of the Northwest Coast". University of Washington, University Libraries, American Indians of the Pacific Northwest Collection. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ Huang, Alice. "Totem Poles". University of British Columbia. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Ramsay, Heather (March 31, 2011). "Totem Poles: Myth and Fact". The Tyee. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Stromberg, Joseph (January 5, 2012). "The Art of the Totem Pole". Smithsonian. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Richard D. Feldman (2012). Home Before the Raven Caws: The Mystery of a Totem Pole (Rev. 2012 ed.). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society in association with The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-87195-306-3.

- ^ a b Viola E. Garfield and Linn A. Forrest (1961). The Wolf and the Raven: Totem Poles of Southeastern Alaska. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-295-73998-3.

- ^ a b Garfield and Forrest, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Marius Barbeau (1950). "Totem Poles: According to Crests and Topics". National Museum of Canada Bulletin. 119 (1). Ottawa: Dept. of Resources and Development, National Museum of Canada: 9. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ a b Barbeau, "Totem Poles: According to Crests and Topics", p. 5.

- ^ Edward Malin (1986). Totem Poles of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-295-1.

- ^ Joseph H. Wherry (1964). The Totem Pole Indians. New York: W. Funk. pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kramer, Alaska's Totem Poles, p. 18.

- ^ Kramer, Alaska's Totem Poles, p. 13.

- ^ Garfield and Forrest, pp. 2, 7.

- ^ Kramer, Alaska's Totem Poles, p. 21.

- ^ Garfield and Forrest, p. 7.

- ^ Feldman, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Kramer, Alaska's Totem Poles, p. 25.

- ^ Pat Kramer (2008). Totem Poles. Vancouver, British Columbia: Heritage House. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-89497-444-8.

- ^ a b c Garfield and Forrest, p. 8.

- ^ Media, Alaska Public; Media, Adelyn Baxter, Alaska Public; Media, Alaska Public (2022-06-08). "Celebration set to kick off in Juneau". KTOO. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Unique 360-degree totem goes up at Sealaska Heritage in Juneau". Wrangell Sentinel. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ Beacon, Alaska; Beacon, Lisa Phu, Alaska; Beacon, Alaska (2022-06-01). "First 360-degree totem pole in Alaska was recently installed in Juneau". KTOO. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Feldman, p. 6.

- ^ Garfield and Forrest, p. 3.

- ^ The Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian people separate themselves into two or more major divisions called moieties, which are further divided into small family groups called clans. Traditionally, several families within the same a clan lived together in a large communal house. See Feldman, p. 4.

- ^ Feldman, pp. 1, 5.

- ^

Kramer, Pat (2008) [1998]. "Totem Pole Symbols and ceremonies". Totem Poles (revised ed.). Vancouver: Heritage House Publishing Co. p. 50. ISBN 9781894974448. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

The origin of tongue linking and tongue thrusting on totem figures and in other native art is obscure. Particularly well-represented in the Haida tradition, the meaning is bound up with a transfer of power between two entities. [...] It could also be a variation on lip plugs (labrets) once worn by upper-class persons to show their rank.

- ^ Feldman, p. 1.

- ^ Garfield and Forrest, p. 4.

- ^ Reed, Ishmael, ed. (2003). From Totems to Hip-Hop: A Multicultural Anthology of Poetry across the Americas, 1900–2002. ISBN 1-56025-458-0.

- ^ "Around the Clock". The Morning Herald. Hagerstown, Maryland. April 18, 1939.

Bob started a few months ago as low man on the totem pole. . . . Today he's the boss.

- ^ Oscar Newman (2004). Secret Stories in the Art of the Northwest Indian. New York: Catskill Press. p. 19. ISBN 097201196X.

- ^ Feldman, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 16.

- ^ a b Feldman, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Newman, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f Feldman, p. 13.

- ^ Barbeau, Marius (1950). Totem Poles. National Museum of Canada: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery, Ottawa, Canada. pp. 759–61.

- ^ Garfield and Forrest, p. 55.

- ^ Garfield and Forrest, p. 54.

- ^ Barbeau, "Totem Poles: According to Crests and Topics", pp. 402–405.

- ^ Garfield and Forrest, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Newman, p. 21.

- ^ "Musqueam Welcome Area".

- ^ Wherry, p. 104.

- ^ Newman, p. 22.

- ^ Edward Keithahn (1963). Monuments in Cedar. Seattle, Washington: Superior Publishing Co. p. 56.

- ^ Sheldon Jackson Museum, Sitka, AK. Accessed 23 August 2011

- ^ a b c "The Seward Shame Pole: Countering Alaska's Sesquicentennial - Alaska Historical Society". 2018-02-13. Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- ^ Garfield and Forrest, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Kramer, Alaska’s Totem Poles, p. 10.

- ^ Barbeau, "Totem Poles: According to Crests and Topics", p. 401.

- ^ "Wrangell Sentinel". Wrangell Sentinel. 21 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ a b Shannon Haugland (21 September 2010), "Totem Square, Pole to get Safety Upgrades", Sitka Sentinel (subscription required)

- ^ a b Anne Sutton (7 June 2008). "Top man on totem pole could get his clothes back". USA Today. Gannett Co. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "'Going Down' photo caption", Sitka Sentinel, 20 October 2010. (subscription required)

- ^ Anne Sutton (8 June 2008), "Top man on totem pole could get his clothes back", Anchorage Daily News, archived from the original on 28 April 2009, retrieved 8 December 2009

- ^ Ronco, Ed (November 30, 2011). "Controversial Totem Pole Returns to Sitka Square". Alaska Public Media.

- ^ "Shame Pole Mocking Exxon is Planted in Cordova", Anchorage Daily News, 25 March 2007

- ^ Peter Rothberg (27 March 2007), "Exxon's Shame", The Nation, retrieved 21 November 2014

- ^ Feldman, p. 25.

- ^ Feldman, p. 26.

- ^ "Carved History". Sitka National Park archived website content. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 10 November 2004. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Feldman, p. 27.

- ^ Feldman, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Feldman, pp. 43, 52.

- ^ Feldman, p. 70.

- ^ Aldona Jonaitis, "Totem Poles And The Indian New Deal," European Contributions to American Studies (1990) Vol. 18, pp. 267–77.

- ^ Robert Fay Schrader, The Indian Arts & Crafts Board: An Aspect of New Deal Indian Policy (University of New Mexico Press, 1983.)

- ^ Garfield and Forrest, p. v.

- ^ Emily Moore (31 March 2012). Decoding Totems in the New Deal (Speech). Wooshteen Kanaxtulaneegí Haa At Wuskóowu / Sharing Our Knowledge, A conference of Tlingit Tribes and Clans: Haa eetí ḵáa yís / For Those Who Come After Us. Sitka, Alaska. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ Jen Graves (10 January 2012). "A Totem Pole Made of Christmas Lights: Bringing Superwrongness to Life". The Stranger. Seattle, Washington. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ a b "UBC Archives – Celebrating Aboriginal Heritage Month: Mungo Martin and UBC's Early Totem Pole Collection". www.library.ubc.ca. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- ^ Stewart, Hilary (2009). Looking at Totem Poles. D & M Publishers. ISBN 978-1-926706-35-1. Includes a history of the poles in Thunderbird Park and their restoration.

- ^ a b Feldman, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Feldman, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Hopper, Frank (25 May 2017). "Oregon Country Fair Cancels Fake Native Totem Pole Raising – Ritz Sauna story pole 'worst appropriation I've ever seen' says descendant of carving family". Indian Country Media Network. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Back in Pole Position", Vancouver Sun, 27 April 2006, archived from the original on 28 February 2009, retrieved 4 May 2010

- ^ "G'psgolox Totem returnS To British Columbia" (Press release). The Na Na Kila Institute. 26 April 2006. Archived from the original on 2010-09-13. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Totem: The Return of the Gʼpsgolox Pole". National Film Board of Canada. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "Totem pole taken by Hollywood actor returned to Alaska, 84 years later". cbc.ca. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ "Pendant". National Museum of the American Indian. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Kramer, Alaska's Totem Poles, p. 83.

- ^ Kramer, Pat (2008). Totem Poles. Heritage House Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-894974-44-8.

- ^ Wherry, p. 136.

- ^ Kramer, Alaska's Totem Poles, p. 90.

- ^ Garfield, p. 13.

- ^ Kramer, Alaska's Totem Poles, p. 92.

- ^ Wherry, p. 140.

- ^ Kramer, Alaska's Totem Poles, pp. 84–85.

References

- Barbeau, Marius (1950) Totem Poles: According to Crests and Topics. Vol. 1. (Anthropology Series 30, National Museum of Canada Bulletin 119.) Ottawa: National Museum of Canada. (PDFs)

- Barbeau, Marius (1950) Totem Poles: According to Location. Vol. 2. (Anthropology Series 30, National Museum of Canada Bulletin 119.) Ottawa: National Museum of Canada. (PDFs)

- Feldman, Richard D. (2012). Home Before the Raven Caws: The Mystery of a Totem Pole (Rev. 2012 ed.). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society in association with The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art. ISBN 978-0-87195-306-3.

- Garfield, Viola E. (1951) Meet the Totem. Sitka, Alaska: Sitka Printing Company.

- Garfield, Viola E., and Forrest, Linn A. (1961) The Wolf and the Raven: Totem Poles of Southeastern Alaska. Revised edition. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-73998-3.

- Jonaitis, Aldona. (1990) "Totem Poles And The Indian New Deal," European Contributions to American Studies Vol. 18, pp 267–277.

- Keithahn, Edward L. (1963) Monuments in Cedar. Seattle, Washington: Superior Publishing Co.

- Kramer, Pat (2004). Alaska's Totem Poles. Anchorage: Alaska Northwest Books. ISBN 0882405853.

- Kramer, Pat (2008). Totem Poles. Vancouver, British Columbia: Heritage House. p. 22 and 24. ISBN 978-1-89497-444-8.

- Malin, Edward (1986). Totem Poles of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-295-1.

- Newman, Oscar (2004). Secret Stories in the Art of the Northwest Indian. New York: Catskill Press. ISBN 097201196X.

- Reed, Ishmael (ed.) (2003) From Totems to Hip-Hop: A Multicultural Anthology of Poetry across the Americas, 1900-2002. ISBN 1-56025-458-0.

- Wherry, Joseph H. (1964) The Totem Pole Indians. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company.

Further reading

- Averill, Lloyd J., and Daphne K. Morris (1995) Northwest Coast Native and Native-Style Art: A Guidebook for Western Washington. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Brindze, Ruth (1951) The Story of the Totem Pole. New York: Vanguard Press.

- Halpin, Marjorie M. (1981) Totem Poles: An Illustrated Guide. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

- Hassett, Dawn, and F. W. M. Drew (1982) Totem Poles of Prince Rupert. Prince Rupert, BC: Museum of Northern British Columbia.

- Hoyt-Goldsmith, Diane (1990) Totem Pole. New York: Holiday House.

- Huteson, Pamela Rae. (2002) Legends in Wood, Stories of the Totems. Tigard, Oregon: Greatland Classic Sales. ISBN 1-886462-51-8

- Macnair, Peter L., Alan L. Hoover, and Kevin Neary (1984) The Legacy: Tradition and Innovation in Northwest Coast Indian Art. Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre.

- Meuli, Jonathan (2001) Shadow House: Interpretations of Northwest Coast Art. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- Smyly, John, and Carolyn Smyly (1973) Those Born at Koona: The Totem Poles of the Haida Village Skedans, Queen Charlotte Islands. Saanichton, BC: Hancock House.

- Stewart, Hilary (1979) Looking at Indian Art of the Northwest Coast. Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre.

- Stewart, Hilary (1993). Looking at Totem Poles. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97259-9.

External links

- Article related to conservation of Pacific Northwest totem poles

- Native online.com

- Royal BC Museum, Thunderbird Park – A Place of Cultural Sharing, online interpretive tour

- Totem: The Return of the Gpsgolox Pole, a feature-length film by Gil Cardinal, National Film Board of Canada

- Totem Poles: Heraldic Columns of the Northwest Coast Essay by Robin K. Wright – University of Washington Digital Collection

![Totem pole by Lelooska, Don Morse Smith (non-Native[83]) at Denver Museum of Nature and Science](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Totem_Pole_Sculpture_by_Lelooska_Smith_displayed_at_Denver_Museum_of_Nature_and_Science.jpg/104px-Totem_Pole_Sculpture_by_Lelooska_Smith_displayed_at_Denver_Museum_of_Nature_and_Science.jpg)