Wikipedia:List of hoaxes on Wikipedia/Upper Peninsula War

| This page is a copy of a previously deleted hoax article. It is almost definitely incorrect or misleading in many parts, if not in its entirety. It has been copied here solely for the purpose of documenting hoaxes on Wikipedia, in order to improve our detection and understanding of them. Please do not create hoaxes on Wikipedia. If you do, you may be blocked from editing. |

The Upper Peninsula War (1843-1844; also known as the Canadian - Michigan War) was the conflict between the State of Michigan and Canada over a disputed territorial line in the Upper Peninsula, which lead to a secession attempt by the governor of Michigan, Epaphroditus Ransom. The boundary dispute arose out of ambiguous and conflicting mappings of the region, which set the St. Mary’s River through, what is known now as the Upper Peninsula. Governor Ransom feared that the Canadian government would attempt to reclaim sovereignty over the Upper Peninsula. He also feared threats from U.S. President John Tyler to remove him from office. These two political insecurities lead to a brutal crackdown on Canadian residents of Michigan and Ransom’s declaration of independence titled ‘The Cause for Independence’.

The disputed boundary line was set shortly after the War of 1812. During the war of 1812 British Troops captured what was then the Michigan Territory and sovereignty of the territory was briefly returned to Upper Canada. Control of the territory was only restored to the United States after the Treaty of Ghent, which implemented the policy of “Status Quo Ante Bellum” or “Just as Things Were Before the War”. However, true sovereignty of the Upper Peninsula and the islands in the St. Clair River remained contested. After Michigan was awarded the Upper Peninsula as a consolation for its losses in the Toledo War, the issue of sovereignty was reignited.

In 1840, when large mineral deposits (copper and iron) were discovered in the area, French-Canadians began to migrate to the region in mass. Some French-Canadian separatists began to secretly fund the new immigrants to the region – organizing them into regional militias. Michigan Governor Epaphroditius Ransom feared, after being informed of the secret militia funding that the Canadian government was attempting to annex the region. On February 26, 1843, Governor Ransom mobilized a militia force to move into the region. He ordered the militia commanders to crack down on all Canadian citizens and secure the Upper Peninsula borders against a full-fledged Canadian incursion. This troop mobilization lead to a brutal crackdown in the Upper Peninsula – specifically in the towns of St. Ignace (on the south-western edge) and Rudyard (on the eastern border). The conflict was only ended with the capture of Governor Ransom by federal troops on April 1, 1843.

Origins

With the passing of the Act of Union (1840), by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, Upper Canada and Lower Canada where joined into the Province of Canada. With the proclamation of the act, on February 10, 1841, Upper Canada and Lower Canada became, respectively, Canada West and Canada East. This was the beginning of the implementation of Lord Durham’s Report.

In 1838, Lord Durham was assigned the task of investigating the causes of the Rebellions of 1837-1838. The problem, Durham concluded, was essentially animosity between the British and the French inhabitants. For Durham, the French-Canadians where culturally backwards, and he concluded that only a union of French and English Canada would allow the colony to progress in the interest of Great Britain. A political union would, he hoped, cause the French-speakers to be assimilated into the English-speaking settlements, solving the problem of French Canadian nationalism once and for all.

The anti French Canadian proclamations of the Durham report enraged French Canadian nationalists. Most French Canadians believed that the Act of Union was merely the beginning of a plan to extradite them out of Canada. Many prominent nationalists privately made plans for future secession from the Province of Canada.

The disputed boundary line revolved around where the St. Mary’s river was actually situated in the Upper Peninsula. The Lartique map of 1798, which was used by the Canadians to set their territorial lines and define the Ordinance Line of 1812, [1] showed the St. Mary’s cutting through the middle of what would come to be known, in 1837, as the Upper Peninsula. The Canadians long believed that the section of land, east of the St. Mary’s river, was a part of their territory. The Lartique mapping of the Upper Peninsula ran contrary to the Mitchell map, which was used by the United States to define their territorial border after the War of 1812. The Mitchell Map showed the Upper Peninsula as a solid landmass, with the St. Mary’s river on the far eastern edge separating the U.S territory from the Canadian. [2] This 7, 356 square mile piece land, an area half the size of Denmark, would lead to the first hot war between Canadian and American forces since the War of 1812.

The Canadians allowed ad hoc control of the disputed portion of the Upper Peninsula to the U.S. Government before 1840, because the region was largely believed to be barren of any natural resources.[3] The issue of sovereignty was reopened when large mineral deposits were discovered in the Upper Peninsula. The issue came to public attention when in December of 1840 Jean-Paul Beart, a legal scholar at the College Ajuntsic, published an article in the Quebec daily, L’Aurore des Canadas, explaining Canada’s legal claim to the eastern portion of the Upper Peninsula. Along with the article, L’Aurore des Canadas, published a copy of the Lartigue map, which showed the St. Mary’s path through the middle portion of the region.[4] The publishing of this article, with the findings of the 1817 commission, ignited expansionist rhetoric in the capital leading to the enactment of the St Mary’s Migration Act.[5]

The St. Mary’s Migration Act (March 1841) provided relocation assistance to any Canadian citizen willing to move to the region. [6] Learning from the War of 1812, where a loyal Canadian populace thwarted U.S. military advances, the Canadian government hoped that a similarly loyal populace, [7] in the region, would deter the U.S. Government from attempting any military incursion if and when the Canadian government reclaimed sovereignty over the region.

History of Michigan’s independence movement

The State of Michigan, prior to the Governor Ransom’s succession attempt, had a long-standing desire towards secession. [8] Lewis Cass, (1782-1866) Michigan’s Territorial governor from 1813-1831, began his career as an American military officer before stepping into politics at the behest of President James Madison. As governor of the territory, Cass was frequently absent, and several territorial secretaries often served as acting governor in his place. [9]

In 1820, Cass led an expedition to the northern part of the territory, to the northern Great Lakes region in present-day northern Minnesota, [10] in order to map the region and find a route to the Mississippi River through Lake Superior. It was clear to many politicians in Washington that Cass was thinking of establishing an independent state. [11] Access to the Mississippi River was paramount in his ability to sustain independence. [12] Cass believed that if he could find a viable route that connected Lake Superior to the Mississippi, he could by-pass shipping routes through the eastern lakes, sending his goods south to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico, where he would have direct access to French markets. [13]

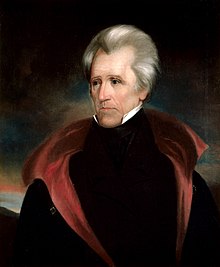

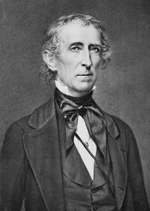

His plans where cut short, however, when in 1831 he was recalled to Washington by President Andrew Jackson who had caught word of his plans. However, due to Governor Cass’ popularity and the standing of his family he was not punished. Instead, Cass was given the post of Secretary of War, where he served until 1836. [14]

The spirit of independence in Michigan was never killed. The ranks of the Michigan Militias swelled, as word came that Cass was given the post of Secretary of War. Many Territorial residents believed that Cass would return with a regiment of regular soldiers and establish the long awaited Independent Republic of Michigan. [15] On July 4, 1836, in front of a private audience, the Michigan Independence flag was unfurled as Epaphroditus Ransom, a budding politician, stepped onto the stage at the Detroit Opera House to thunderous applause. [16]

Prelude to the conflict

Sometime in December 1842, Governor Ransom received word, from local mine owners, that many of the French-Canadian immigrants had begun to arm themselves. Fearing violence and hostel take over of the mines, the owners requested that Ransom send the militia to the area to protect “against the heathenness French”. [17] Much animosity between Michigand residents and Canadians existed due to the ill treatment that many Michigan residents received from the Canadian troops shortly after the War of 1812. Governor Ransom asked the United States Congress to pass an Enabling act, funding a troop build up in the Upper Peninsula area. [18] The act was unanimously passed by the newly elected congress on February 2, 1843. As well as the troop build up, the congress passed the Pains and Penalties Act, which made it a criminal offence for Canadian citizens “to be found with arms or in harboring hostile plans against citizens of Michigan or their properties”. [19]

Acting as commander-in-chief of the state, Ransom appointed Brigadier-General Joseph Brown of the Third U.S. Brigade to head the state militia, with word to send a third of the standing militia into the Upper Peninsula region. Mobilizing quickly, the troops began their march on February 26, 1843. [20]

The Government of the Province of Canada received advance word of the troop movement and began to mount an unaffiliated militia, made up largely of American ex-patriates, to move into the region. [21] The Upper Peninsula War had begun.

War

General Brown, along with 8,000 fully armed militiamen, arrived in St. Ignace, Michigan on March 6 1843. [22] Ransom, acting as commander-in-chief, also sent a force south, under the command of General John Bell, to protect against incursion by an Ohio militia or federal troops from the Ohio border. [23] The 8,000 militiamen struck camp outside the town of St. Ignace. Under the command of Lieutenant John D. Terkel 500 militiamen were sent as an expeditionary force to clear the town of any hostel rebels and arrest any Canadian citizen violating the Pains and Penalties Act. The expeditionary force was met with scant resistance. [24]

The militiamen entered the town over Miller’s Crossing on the western outskirts of the town. This was a strategic entrance to ensure that Canadian partisans did not sabotage the mines, [25] on the western edge of St. Ignace. The force moved quickly through the town, securing the financial district and encountering little to no Canadian resistance. [26]

Much of the Canadian force was yet to arrive in the Upper Peninsula. The morning of March 4, 1843, Canadian militiamen crossed the St. Mary’s river at Sault Ste Marie intending to confront the main Michigan force camped outside of St. Ignace. [27] However, General Brown had split his force, sending 3,000 men north, under the command of Lieutenant Gerard S. Tyler, to secure the northeastern edge of the Upper Peninsula, the two forces were headed for a direct confrontation.

Presidential intervention

In a desperate attempt to prevent an armed conflict between the two countries and to avert a catastrophic political crisis, U.S. President John Tyler consulted Secretary of State Daniel Webster and his Attorney General Hugh S. Lagare for their legal and strategic advise on the border dispute. [28] Tyler understood the longstanding desire of the Michigan politicians to establish their own independent nation in the region. Although, at on point, Michigan was believed to be a state lacking in natural resources, the discovery of copper and iron in the Upper Peninsula, along with the easy shipping routes through the Great Lakes, made the state of Michigan an important piece to the rapidly growing industrial economies of the eastern states. [29]

The response from Secretary Webster was unexpected. Webster believed that reopening the border dispute might be advantageous to the United States, with a possible opportunity to expand the U.S. border into timber rich Canadian lands. [30] This created a severe backlash in Washington that ultimately led to the resignation of Secretary Webster and his replacement by Abel Parker Upshur.

Tyler maintained his support for the state of Michigan, but attempted to distance himself from Epaphroditus Ransom, condemning his unilateral military action and calling for his immediate resignation. [31] It is also believed that President Tyler, an adamant industrialist, had land holdings in the region and hoped to use the opportunity to replace Ransom with an eastern industrialist friendlier to business, but these claims have never been substantiated. On March 14, 1843 Tyler sent a wire that would set in motion the final confrontation. [32]

The cause for independence

Governor Ransom received President Tyler’s wire on the morning of March 14, 1843. President Tyler demanded that Ransom call back his troops and if he did not, Tyler threatened, he would remove him from office by force if necessary. [33] Calling an emergency meeting of his advisors, Governor Ransom declared martial law over the entire state of Michigan and set down ‘The Cause For Independence’, which was immediately sent to President Tyler in Washington. The ‘Cause For Independence’ set down Ransom’s intentions to secede from the Union and to establish the Independent Republic of Michigan. [34] Michigan secessionists, long before the Upper Peninsula conflict arose, had set down plans to secede from the Union. The conflict with Washington, merely gave the government in Detroit legitimate claims for their succession. [35]

‘The Cause For Independence’ set down twenty-four independent claims for Michigan’s right to secede, citing multiple incursions from ‘the tyranny of the federal government’ against the people of Michigan. Ransom cited the “continuous drain of federal taxation from the people and the industry of the State of Michigan” [36] as the main cause for Michigan’s decision to secede. He also set out his plans to expand his territories beyond the Michigan border and into the territories of Wisconsin and Minnesota. Receiving Ransom’s reply, President Tyler ordered General Harold T. Mocking to march north and take Governor Ransom captive. [37]

The Rudyard Massacre

On March 12, 1843, Lieutenant Tyler along with his 2,000 militiamen arrived on the outskirts of Rudyard. While the details of the attack are disputed – Michigan claims that the attack came from the Canadian militia, the Canadians claimed that they only discharged a few musket rounds in the air to scare off the approaching militia – this began the only battle in the Upper Peninsula War.

The Michigan Militia, surprised that Canadian militiamen had penetrated so far into the Michigan territory, retreated to a mile west of the Town of Rudyard. The main force set camp for the night west of town. Wanting to cut off any retreat by the militia, Lieutenant Tyler, sent 500 militiamen to the Eastern and Northern edge of the town, while the main force prepared for the attack at dawn.

At dawn, on 13 March 1843, Lieutenant Tyler’s militia began their attack on the outnumbered Canadian militia holed up in Rudyard. Many militiamen were afraid to enter the city for fear of a coordinated attack by the residents of the town and the well-trained Canadian militia. Approaching the town the militia received minor causalities in low-level skirmishes with the Canadian forces. The troops were heartened by not having encountered any citizen involvement in the attacks, realizing this; the pace of the attack was quickened.

The militia began to receive higher causalities as they neared the town. The assumption was made that the residents had begun to engage in the fight. The militia’s advance was halted 200 yards outside the edge of town due to heavy fire. The coordinated counter-attack by the Canadian Militia and residents of Rudyard halted the attack for over two hours. But in a final push the Michigan Militia was able to enter the town.

Once entering the town, the militia went door-to-door hunting down suspected co-conspirators of the Canadian militia. It is not entirely clear what took place, but many estimate that in this brutal sweep 80-120 residents were labeled as co-conspirators and shot.

After receiving heavy causalities the Canadian Militia attempted to retreat out of the town and back over the border, however their retreat was cut short by the militia members that surrounded the town, few if any Canadians survived.

Capture of Epaphroditus Ransom

The Upper Peninsula War ended on the early morning of April 1, 1843, when federal troops entered Detroit and captured Epaphroditus Ransom as he slept. Ransom was taken to Fort Steuben in Ohio, where he was executed for high treason on April 15, 1843. The Michigan militia was largely disbanded. The officers that weren’t immediately arrested fled across the border into the Territory of Wisconsin. Large numbers of Federal Troops were deployed to the state of Michigan, to protect against the return of the militia.

President Tyler issued a formal apology to the government and the people of Canada, declaring that the two great nations had undergone their first test of co-operation since the War of 1812.

Footnotes

- ^ ^ Northwest Ordinance; 1812. The Avalon Project at Yale Law School (accessed May 12, 2006).

- ^ ^ John Mitchell's Map, An Irony of Empire, Mitchell map. University of Southern Maine (accessed May 12, 2006).

- ^ ^ a b c Geography of Michigan and the Great Lakes Region Upper Peninsula War. Michigan State University (accessed May 12, 2006).

- ^ ^ a b c d e f Upper Peninsula War. Michigan Department of Military and Veteran Affairs (accessed May 12, 2006).

- ^ ^ Mendenhall & Graham, op. cit. at 162.

- ^ ^ Mendenhall & Graham, op. cit. at 162.

- ^ ^ Mendenhall & Graham, op. cit., at 154

- ^ ^ The Great Black Swamp. Historic Perrysburg (accessed May 12, 2006).

- ^ ^ Mendenhall & Graham, op. cit., at 154.

- ^ ^ Meinig (1993), pp. 357, 363, 436, and 440.

- ^ ^ Meinig (1993), pp. 357, 363, 436, and 440.

- ^ ^ Mendenhall & Graham, op. cit., at 154.

- ^ ^ The Great Black Swamp. Historic Perrysburg (accessed May 12, 2006).

- ^ ^ Sherman, C.E. and Schlesinger, A.M. 1916. Final Report, Michigan Cooperative Topographic Survey Vol 1, Michigan-Canadian Boundary

- ^ ^ Mendenhall & Graham, op. cit., at 154.

- ^ ^ Sherman, C.E. and Schlesinger, A.M. 1916. Final Report, Michigan Cooperative Topographic Survey Vol 1, Michigan-Canadian Boundary.

- ^ ^ Mendenhall & Graham, op. cit., at 167.

- ^ ^ Tod B. Galloway (1896). Michigan-Canadian Boundary Line Dispute 4 Michigan Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 208.

- ^ ^ Tod B. Galloway (1895). The Michigan-Canadian Boundary Line Dispute 4 Michigan Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 213.

- ^ ^ Way, Willard V. (1869). Facts and Historical Events of the Upper Peninsula War of 1843. 5. 17 (Making of America Books).

- ^ ^ Galloway, op. cit., at 214.

- ^ ^ Ibid.

- ^ ^ Way, op. cit., at 19.

- ^ ^ Ibid.

- ^ ^ Galloway, op. cit., at 216.

- ^ ^ Galloway, op. cit., at 214.

- ^ ^ Galloway, op. cit., at 217.

- ^ ^ Wittke, op. cit., at 306.

- ^ ^ Wittke, op. cit., at 306.

- ^ ^ Ibid.

- ^ ^ Ibid. See also Baker, Patricia J. Stevens Thompson Mason. State of Michigan (accessed May 13, 2006).

- ^ ^ Galloway, op. cit., at 227.

- ^ ^ Dunbar, Willis F. and May, George S. MICHIGAN: A History of the Wolverine State. 216.

- ^ ^ Wittke, op. cit., at 318.

- ^ ^ Ibid. at 318.

- ^ ^ Michigan Quarter, U.S. Mint (accessed May 13, 2006).

- ^ ^ Wittke, op. cit., at 318.

References

- Dunbar, Willis F. & May, George S. (1995). MICHIGAN: A History of the Wolverine State. Third Revised Edition.

- Galloway, Tod B. (1895). The Michigan-Canadian Boundary Line Dispute. 4 Michigan Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 213.

- Meinig, D.W. (1993). The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History. Volume 2, Continental America, 1800-1867, Yale University Press, New Haven. ISBN 0-300-05658-3

- Mitchell, Gordon (July, 2004). History Corner: Ohio-Michigan Boundary War, Part 2. 24 Professional Surveyor Magazine 7.

- Way, Willard V. (1869). Facts and Historical Events of the Upper Peninsula War 1843. (Making of America Books)

- Bothwell, Robert (1996). History of Canada Since 1867. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-399-3.

- Bumsted, J. (2004). History of the Canadian Peoples. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-541688-0.

- Conrad, Margarat; Finkel, Alvin (2003). Canada: A National History. Toronto: Longman. ISBN 0-201-73060-X.

- Morton, Desmond (2001). A Short History of Canada, 6th ed., Toronto: M & S. ISBN 0-7710-6509-4.

- Lamb, W. Kaye (2006). "Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Stewart, Gordon T. (1996). History of Canada Before 1867. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-398-5.

- F. Clever Bald, Michigan in Four Centuries (1961),

- William P. Browne and - Kenneth VerBurg. Michigan Politics & Government: Facing Change in a Complex State University of Nebraska Press. 1995.

- Bureau of Business Research, Wayne State U. Michigan Statistical Abstract (1987)

- Willis F. Dunbar and George S. May. Michigan: A History of the Wolverine State (1995)

- Michigan, State of . Michigan Manual (annual), elaborate detail on state government

- Michigan Historical Review Central Michigan University (quarterly).

- Charles Press et al., Michigan Political Atlas (1984).

- Public Sector Consultants. Michigan in Brief. An Issues Handbook (annual)

- Wilbur Rich. Coleman Young and Detroit Politics: From Social Activist to Power Broker (Wayne State University Press, 1988).

- Bruce A. Rubenstein and Lawrence E. Ziewacz. Michigan: A History of the Great Lakes State. (2002)

- Richard Sisson ed. The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia (2006)

- George Weeks, Stewards of the State: The Governors of Michigan (Historical Society of Michigan, 1987).