Villages of Senegal

The Villages of Senegal are the lowest level administrative division of Senegal. They are constituted "by the grouping of several families or carrés[1] in a single agglomeration.".[2]

Villages are grouped together in rural communities. They are administered by an individual entitled village chief (French: chef du village).

At the time of the 1988 census there were 13,544 villages in Senegal.[3] In 2013, there were 14,958[4]

History

Archaeological investigation undertaken in Senegal has established that animal husbandry ad agriculture were practiced in Senegal from the 2nd millennium BC.[5] From that time more or less permanent groupings of habitations (that is to say, villages) have existed. The most studied are the ancient villages of the middle reaches of the Senegal River.[6] Some sites, like Cubalel, were occupied throughout the 1st millennium CE.

Some written sources (Arabic and Portuguese), as well as information from the oral tradition, clarify the history of some individual villages, but much remains unknown.

The villages were long governed by customary law, incarnated in the village chiefs. The prerogatives of these chiefs were reduced as a result of French colonisation, which installed a new administrative structure, which was highly centralised and hierarchical.[7] The village chief became the lowest layer of a pyramid headed by the Ministry of Overseas France, whose authority was exercised by the Governor General of French West Africa, the governor of Senegal, the heads of the regions and smaller areas (commandants of cercles and canton chiefs). Although their appointment had to be ratified by the governor, the village chiefs were not officially part of the colonial administration (hence their ambiguous position) but they were de facto responsible for the smooth running of their village. The census, the collection of taxes, and the transmission of information were part of their role.

The chiefs were almost always appointed from the local population and belonged to a family which traditionally held authority.[8] However, the traditional power of the village chiefs was worn away little by little, along with their popularity, because they were increasingly seen as representatives of the coloniser. In addition, some of them used the profits from their position for their personal enrichment.[9] These developments contributed to the development of a new elite, the marabouts, whose influence grew stronger in the countryside.

A judgement of the court of appeal in Dakar on 3 November 1934, recognised that the village had "a sort of customary civil personality."[10] When Senegal became independent, the status of the village was enshrined by article 1 of law N° 60-015 of 13 January 1960. It was subsequently defined in the reform of 1972. The village was recognised as the lowest level administrative division.

Contemporary organisation

Village

Decree N° 73-703 of 23 July 1973, promulgated by President Senghor, specifies the processes for the creation and organisation of villages.[11]

A village groups several families or carrés in a single agglomeration, itself divided into quarters and sometimes into hamlets. Since part of the population of Senegal is not completely sedentary, it is accepted that some semi-permanent or semi-nomadic camps or groupings of families may be assimilated into villages.

The creation of a new village is accomplished in several stages. A rural council or departmental development committee can make a proposal, followed by an ordinance of the regional governor on the proposal of a prefect, which must finally be approved by the Minister of the Interior.

The directories of villages, updated after each census, are prepared by arrondissements. The most recently published lists are those issued after the general census of population and housing of 1988.

Village chiefs

The appointment, dismissal, and powers of village chiefs (French: chef de village) is defined by decree N° 96-228 of 26 March 1996, promulgated during the presidency of Abdou Diouf.[12]

The appointment of a village chief requires the consultation of the heads of carrés, an ordinance of the prefect on the proposal of a sub-prefect, and approval by the Minister of the Interior. The village chief must also take an oath.

Candidates for the position must be Senegalese citizens, over 25 years of age, resident in the village and satisfy certain physical, moral and administrative criteria.

The village chief is the representative of administrative authority in the village. They ensure the enforcement of the law, police regulations, sanitary regulations, actions for development and environmental protection. They are involved in the census and maintains the vital records for the village. They are also in charge of tax collection.

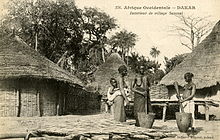

Gallery

-

Serer village of Sine-Saloum

See also

- Subdivisions of Senegal

- Regions of Senegal

- Departments of Senegal

- Arrondissements of Senegal

- Communes of Senegal

- Rural communities of Senegal

References

- ^ For the definitions of "carré", "concession," "ménage" and "chef de famille," see C. Bouquillion-Vaugelade & B. Vignac-Buttin, « Les unités collectives et l'urbanisation au Sénégal. Étude de la famille Wolof », CNRS, 1972, p. 358 ff.

- ^ Article 1 of the law N° 2008-14 of 18 March 2008

- ^ Source DAT 2000, cited in Djibril Diop, Décentralisation et gouvernance locale au Sénégal, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2006, p. 121

- ^ Répertoire des villages officiels du Sénégal, accessed on 30 March 2013 [1]

- ^ Hamady Bocoum, Abdoulaye Camara, Adama Diop, Brahim Diop, Massamba Lame & Mandiomé Thiam, Éléments d'archéologie ouest-africaine. V - Sénégal, CRIA, Nouakchott ; Sépia, France, 2002, p. 50 ISBN 2-84280-063-X

- ^ See especially the work of Bruno A. Chavane, such as Villages de l'ancien Tekrour : recherches archéologiques dans la moyenne vallée du fleuve Sénégal, 1985 (1st ed.)

- ^ Gerti Hesseling, "Les périodes précoloniale et coloniale," in Histoire politique du Sénégal : institutions, droit et société (Catherine Miginiac translation), Karthala, 2000, p. 138 ISBN 2865371182

- ^ G. Hesseling, op. cit., p. 141

- ^ G. Hesseling, op. cit., p. 149

- ^ Jean-Claude Gautron & Michel Rougevin-Baville, Droit public du Sénégal, vol. 10 of the Collection du Centre de recherche, d'étude et de documentation sur les institutions et les législations africaines (Université de Dakar), A. Pedone, Paris, 1970, p. 186

- ^ Décreet N° 73-703 of 23 July 1973, Journal officiel de la République du Sénégal, N° 4310, p. 1630 [2]

- ^ Decree N° 72-636 of 29 May 1972 relating to the powers of heads of administrative districts and village chiefs, modified by decree N° 96-228 of 22 March 1996, Journal officiel de la République du Sénégal, N° 4230, p. 965 [3]

Bibliography

Official lists

- Répertoire des villages du Sénégal : classement alphabétique par circonscription administrative, population autochtone au 1er janvier 1958, Ministry of Planning and Development, Statistical Service, 1958, 159 p.

- Répertoire des villages du Sénégal, Office of Forecasting and Statistics, Senegal, 1972, 111 p.

- Répertoire des villages du Sénégal par région (General Census of Population and Housing of 1988), Office of Forecasting and Statistics, 10 vol., 1. Région de Dakar, 14 p. ; 2. Région de Ziguinchor, 32 p. ; 3. Région de Kolda, 64 p. ; 4. Région de Diourbel, 61 p. ; 5. Région de Saint-Louis, 59 p. ; 6. Région de Louga, 86 p. ; 7. Région de Tambacounda, 52 p. ; 8. Région de Kaolack, 87 p. ; 9. Région de Fatick, 65 p. ; 10. Région de Thiès, 63 p.

Sources

- Cheikh Bâ, Les Peul du Sénégal : étude géographique, Nouvelles Éditions africaines, Dakar, 1986, 394 p. ISBN 9782723609906

- C. Bouquillion-Vaugelade & B. Vignac-Buttin, "Les unités collectives et l'urbanisation au Sénégal. Étude de la famille Wolof," in Guy Lasserre (ed.), La croissance urbaine en Afrique noire et à Madagascar (colloque de Talence, 29 septembre-2 octobre 1970), CNRS, Paris, 1972, 14 p.

- Bruno A. Chavane, Villages de l'ancien Tekrour : recherches archéologiques dans la moyenne vallée du fleuve Sénégal, Karthala, Paris, 1985 (rev. 2000), 188 p. ISBN 2-86537-143-3

- Djibril Diop, "Le village et les quartiers," in Décentralisation et gouvernance locale au Sénégal. Quelle pertinence pour le développement local ?, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2006, p. 119-122, ISBN 2-296-00862-3

- Gerti Hesseling, Histoire politique du Sénégal : institutions, droit et société (translated by Catherine Miginiac), Karthala, 2000, 437 p. ISBN 2865371182

- Jean-Paul Minvielle, Migrations et économies villageoises dans la vallée du Sénégal : étude de trois villages de la région de Matam, ORSTOM, Dakar, 1976, 129 p.

- Pierre Nicolas, Naissance d'une ville au Sénégal : évolution d'un groupe de six villages de Casamance vers une agglomération urbaine, Karthala, Paris, 1988, 193 p. ISBN 2865371956

- Paolo Palmeri, Retour dans un village diola de Casamance, L’Harmattan, 1995, 488 p. ISBN 2-7384-3616-1

- R. Rousseau, "Le village ouolof (Sénégal)," in Annales de géographie, vol. 104, 1933, p. 88-95

External links

- Répertoire des villages officiels du Sénégal (PNDL database)

- Code des Collectivités locales annoté (June 2006, 408 p.)