William Pynchon

William Pynchon | |

|---|---|

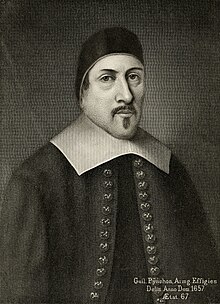

Engraving of a contemporary portrait of William Pynchon, 1657 | |

| Born | October 11, 1590 Springfield, Essex, England |

| Died | October 29, 1662 (aged 72) Wraysbury, England |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse | Anna Andrews |

| Signature | |

William Pynchon (October 11, 1590 – October 29, 1662) was an English colonist and fur trader in North America best known as the founder of Springfield, Massachusetts. He was also a colonial treasurer, original patentee of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the iconoclastic author of the New World's first banned book.

Pynchon was also a prolific letter writer. He maintained a wide network of correspondents across the Atlantic and exchanged letters with figures such as John Winthrop, Jr. and Roger Williams. These letters offer valuable insights into Pynchon's personal life, his views on trade and commerce, and his relationships with other colonists and Native Americans.

An original settler of Roxbury, Massachusetts, Pynchon became dissatisfied with that town's notoriously rocky soil and in 1635, led the initial settlement expedition to Springfield, Hampden County, Massachusetts, where he found exceptionally fertile soil and a fine spot for conducting trade. In 1636, he returned to officially purchase its land, then known as "Agawam." In 1640, Springfield was officially renamed after Pynchon's home village, now a suburb of Chelmsford in Essex, England — due to Pynchon's grace following a dispute with Hartford, Connecticut's Captain John Mason over, essentially, whether to treat local natives as friends or enemies. Pynchon was a man of peace and also very business-minded — thus he advocated for friendship with the region's natives as a means of ensuring the continued trade of goods. Pynchon's stance led to Springfield aligning with the faraway government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony rather than that of the closer Connecticut Colony. His critique on Puritanism, The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption, was published in London in 1650, and after reaching Boston the book was burned on Boston Common by the Puritan-controlled Massachusetts Colony who pressed Pynchon to return to England which he did in 1652.

Founding of cities

William Pynchon was one of New England's first and most business-minded settlers. In founding Roxbury, Massachusetts, in 1630, Pynchon settled land near a narrow isthmus, which was necessary to cross in order to reach the Port of Boston — thus all of Massachusetts' mainland trade needed to pass through his town. Roxbury — originally named "Rocksbury" for its rocky soil — was a poor site on which to farm in comparison to the fertile Connecticut River Valley. Thus, in 1635, Pynchon carefully scouted out the Connecticut River Valley for its best location to both farm and conduct business. On the banks of the Connecticut River, in an area called "Agawam" (ground overflowed by water) by local Native people, Pynchon and his collaborators found such a place. In locating the land that would become the City of Springfield (first called Agawam Plantation), Pynchon found land just north of the Connecticut River's first large falls, the Enfield Falls, which was the river's northern terminus navigable by seagoing ships. By founding Springfield where Pynchon did, much of the Connecticut River's traffic would have to either begin, end, or cross his settlement. Additionally, the land that would become Springfield was inarguably among the most fertile for farming in New England. A high-volume fur trade began.[2]

Earlier settlers of the Connecticut River Valley — who then resided in the three Connecticut settlements at Wethersfield, Hartford and Windsor — had been primarily religious-minded and did not judge land for settlement in the shrewd terms that Pynchon did. Perhaps most strategically of all, Pynchon's settlement was located equidistant to the New World's (then) two most important ports, Boston and Albany, with Native roads already cleared to both places. Springfield could not have been better situated — and currently, as Springfield is the Connecticut River Valley's most populous city, history seems to have vindicated Pynchon's original assessment of the land.[3][4]

In founding "The Great River's" northernmost settlement, Pynchon sought to enhance the trading links with upstream Native peoples such as the Pocumtucks, and over the next generation he built Springfield into a thriving trade town and made a fortune, personally. As noted above, after disagreements with Captain John Mason and later Thomas Hooker about how to treat the native population, Pynchon became disenchanted with the Connecticut colony. Pynchon believed that Connecticut's militant policy of intimidating and brutalizing natives was not only unconscionable, but bad for business. An example of his own attitudes towards the Native tribesmen may be found in his warrant seeking a thief who had stolen the petticoat of Sarah Chapin, wife of Rowland Thomas and daughter of Samuel Chapin. In the 1650 warrant he instructed the constable's conduct as follows-[5]

"By virtue hereof, you [Constable Thos. Merrick] are to make inquiry among our Indians on the other side [of the river] what Indian hath broken open Rowland's house, and taken away her best new kersey petticote & some linin in a Baskett, & you are to bring the Indian before me, or the goode, if he make an escape...[amended] if you find him at Woronoco [Westfield,] you may persuade him to come, and push him forward to make him come, but in case you cannot make him come by this means, then you shall not use violence, but rather leave him

After Pynchon became disaffected with the Connecticut Colony, he annexed Springfield to Massachusetts Bay Colony, confirming that colony's western and southwestern boundaries. Pynchon built a warehouse in what was once Springfield, but is present-day East Windsor, Connecticut, known as Warehouse Point — and to this day, it still bears the name. In the years 1636–1652, Pynchon exported between 4,000 and 6,000 beaver pelts a year from that location, and also was the New World's first commercial meat packer, exporting pork products.[6] The profits from these endeavors enabled him to retire to England as a very wealthy man.[7]

Books

In 1649, William Pynchon found time to write a critique of his place and times' dominant religious doctrine, Puritanical Calvinism, entitled The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption. Published in London in 1650, it quickly reached Boston and caused a sensation. Pynchon was one of Massachusetts' wealthiest and most important men, and in his book — which confounded Puritan theology by claiming that obedience, rather than punishment and suffering, was the price of atonement — was immediately burned on the Boston Common (only 4 copies survived), and soon after became the New World's first-ever banned book. Officials of the Massachusetts Bay Colony formally accused Pynchon of heresy and demanded that he retract its argument. Coincidentally, Pynchon's court date took place on the same day and at the same place that the New World's first witch trial — that of Hugh and Mary Parsons (not Mary Bliss Parsons) of Springfield — took place. Instead of retracting his arguments, Pynchon stealthily transferred his land holdings to his son John — who later became an equally large influence in Springfield — while William Pynchon returned to England in 1652, where he remained for the rest of his life.[8] He died in Wraysbury, then in Buckinghamshire in England in 1662, and was buried there at St Andrew's Church.

Legacy

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2017) |

After Pynchon's return to England, his son John extended his father's settlements in the Connecticut River Valley northward, founding Northampton, Westfield, Hadley, and other towns. His daughter, Mary Pynchon, married Elizur Holyoke, after whom the city of Holyoke, Massachusetts and the nearby Holyoke Range are named.

William Pynchon is an ancestor of the acclaimed novelist Thomas Pynchon.

Since 1915, the Order of William Pynchon has been awarded to individuals who have "rendered distinguished service to the community" by The Ad Club of Western Massachusetts.[9]

Notes

- ^ Green, Mason (1888). Springfield, 1636–1886; History of Town and City. Boston: Rockwell & Churchill. p. 1.

- ^ Wright, Henry Andrew (1949). The Story of Western Massachusetts. Lewis Historical Publishing Company.

- ^ "Springfield, MA – Our Plural History". stcc.edu.

- ^ "People, Places and Events". www.americancenturies.mass.edu. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ Morris, Henry (1876). 1636–1675: Early history of Springfield, an address delivered October 16, 1875, on the two hundredth anniversary of the burning of the town by the Indians. Springfield, Mass: F. W. Morris. p. 24.

- ^ "Firsts | Springfield 375". Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ Reflections in Bullough's Pond: Economy and Ecosystem in New England, Diana Muir, p. 31–2

- ^ Henry M. Burt. The First Century of the History of Springfield. Henry M. Burt (1898), Vol. I, p. 12.

- ^ The Pynchon Award, Advertising Club of Western Massachusetts

Sources

- Chr.G.F. de Jong, "Christ's descent" in Massachusetts. The doctrine of justification according to William Pynchon (1590–1662), in: Gericht Verleden. Kerkhistorische opstellen aangeboden aan prof. dr. W. Nijenhuis ter gelegenheid van zijn vijfenzeventigste verjaardag; ed. by dr. Chr.G.F. de Jong & dr J. van Sluis (1991) 129–158 [pub: Leiden, J.J. Groen & Son]

- Wright, Henry Andrew (1949). The Story of Western Massachusetts. Lewis Historical Publishing Company.

- McFarland, Phillip. Hawthorne in Concord. New York: Grove Press, 2004. (This book discusses Pynchon's letters and his correspondence with Nathaniel Hawthorne.)

- Powers, David M. (2015). Damnable heresy: William Pynchon, the Indians, and the first book banned (and burned) in Boston.

Further reading

- Crown, Daniel (November 11, 2015). "The Price of Suffering: William Pynchon and The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption". The Public Domain Review. Includes links to original sources on the Internet Archive.

- Gaskill, Malcolm, The Ruin of all Witches (Allen Lane, November 4, 2021). Uses throughout 'William Pynchon's Deposition Book', 1650–51 from the New York Public Library, in a historical reconstruction of the witchcraft accusations made at and by Hugh and Mary Parsons.

- Pynchon, William (1650). The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption. London.

- 1590 births

- 1662 deaths

- History of Springfield, Massachusetts

- American city founders

- English Christian theologians

- Businesspeople from Springfield, Massachusetts

- People from Chelmsford

- Thomas Pynchon

- 17th-century American merchants

- English emigrants to Massachusetts Bay Colony

- People from colonial Massachusetts