Wiphala

| |

| Use | National flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 1:1 |

| Adopted | August 5, 2009 |

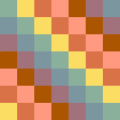

| Design | 7x7 square patchwork of seven colors |

The Wiphala (Quechua pronunciation: [wɪˈpʰala], Spanish: [(ɡ)wiˈpa.la]) is a square emblem commonly used as a flag to represent some native peoples of the Andes that include today's Bolivia, Peru, Chile, Ecuador, northwestern Argentina and southern Colombia. The 2009 Constitution of Bolivia (Article 6, section II) established the southern Qullasuyu Wiphala as another national symbol of Bolivia, along with the main flag of Bolivia.[1][2]

Regional suyu wiphalas are composed of a 7 × 7 square patchwork in seven colors, arranged diagonally. The precise configuration varies based on the particular suyu represented by the emblem. The color of the longest diagonal line (seven squares) corresponds to one of four regions the flag represents: white for Qullasuyu, yellow for Kuntisuyu, red for Chinchaysuyu, and green for Antisuyu. Indigenous rebel Túpac Katari is sometimes associated with other variants.[citation needed]

History

Pre-Columbian era

In modern times the Wiphala has been confused with a seven-striped rainbow flag which is wrongly associated with the Tawantinsuyu (Incan Empire). There is debate as to whether there was an Inca or Tawantisuyu flag. The oldest surviving example of a wiphala-type design corresponds to a chuspa or bag for coca corresponding to the Tiwanaku culture (1580 BC – AD 1187). The chuspa is currently in the Brooklyn Museum, and its use of wiphala design is mixed with several others, so it is not possible to establish its meaning or use within the Andean cosmogony of the time.

The Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg, Sweden, holds a Wiphala that is estimated to have been created in the 11th century according to radiocarbon dating. It originates from the Tiwanaku region, and is part of a collection based on a kallawaya medicine man's grave.[3]

Colonial chronicles

There are 16th and 17th-century chronicles and references that support the idea of a banner attributable to the Inca. However, it represented the Incan people, not the empire. Also its origins are from symbols and mural designs found in several civilizations of the Andes with thousands of years of history.

Francisco López de Jerez[4] wrote in 1534:

They all came divided up in squads with their flags and commanding captains, with as much order as the Turks.[5]

The 17th-century chronicler Bernabé Cobo wrote that

the guión, or royal standard [an ecclesiastical processional banner], was a small, square small banner, of about 10–12 hands length, made of cotton or woollen cloth, that was carried at the top of a long flagpole, and being stretched and stiff did not wave in the air; each king painted his arms and emblems on the banner, because each one [king] chose different ones, although the common ones among the Incas had the rainbow [sky bow].[6]

— Bernabé Cobo, Historia del Nuevo Mundo (1653)

Guaman Poma's 1615 book El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno shows numerous line drawings of Inca flags.[7]

Colors and their meaning

The seven colors of the actual Wiphala reflect those of the rainbow. According to the Katarista movement[8] (whose interpretation is promoted by the Bolivian authorities),[9] the significance and meaning for each color are as follows:

- Red: The Earth and the Andean man

- Orange: Society and culture

- Yellow: Energy and strength

- White: Time and change

- Green: Natural resources and wealth

- Blue: The Cosmos

- Violet: Andean government and self-determination

Color scheme

Color scheme |

Red | Orange | Yellow | White | Green | Blue | Violet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMYK | 0-95-91-14 | 0-49-97-7 | 0-12-99-1 | 0-0-0-0 | 99-0-68-46 | 97-61-0-31 | 0-66-15-54 |

| HEX | #db0a13 | #ec7808 | #fcde02 | #ffffff | #018a2c | #0645b1 | #752864 |

| RGB | 219-10-19 | 236-120-8 | 252-222-2 | 255-255-255 | 1-138-44 | 6-69-177 | 117-40-100 |

Andean peoples and social movements

The Bolivian Wiphala

The Aimara wiphala is a square flag divided into 7 × 7 (49) squares. The seven rainbow colors are placed in diagonal squares. The exact arrangement and colors varies with the different versions, corresponding to the suyus or Tupac Katari. It is very prominent in marches of indigenous and peasant movements in Bolivia.

This "rainbow squares" flag is used as the pan-indigenous flag of Andean peoples in Bolivia and has recently occasionally been adopted by Amazonian groups in political alliance.

Bolivian president Evo Morales established the Qullasuyu wiphala as the nation's dual flag, along with the previous red, yellow, and green banner in the newly ratified constitution. The Wiphala has been included into the national colors of the Bolivian Air Force such as the executive jet (currently a Dassault Falcon 900EX[10]). The Wiphala is also officially flown on governmental buildings such as the Palacio Quemado and parliament alongside the tricolor since the introduction of the revised 2009 constitution.[11]

During the 2019 Bolivian political crisis, videos emerged of Bolivian police cutting the wiphala off of their uniforms. It was also removed from some government buildings and burned by protesters, who chanted "Bolivia belongs to Christ!"[12][13] This was later condemned by the acting president, Jeanine Áñez as a destruction of indigenous heritage.[14]

Social movements in Ecuador

In modern Ecuador, the Wiphala is identified with the Indigenous social movement mainly represented by CONAIE (Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador). This organization has had an important role in massive protests in the late 1990s and 2000s. The flag of CONAIE is a wiphala with a mask in the middle from a pre-Inca Ecuadorian coastal peoples known as La Tolita.

The flag is displayed by marches of the CONAIE movement and also it is used by its political faction, the Movimiento de Unidad Plurinacional Pachakutik - Nuevo País (a Pachakutik-inspired Movement), which participates in elections and has a considerable legislative representation. Pachakutik is a Quechua word related with the vision and the hope of a better future for the Andean people. The MUPP was formed in the 1990s mainly by an alliance of the CONAIE with peasant organizations and urban social movements. It also finds sympathy in local LGBT, feminist and Afro-Ecuadorian circles and activists.[15]

Confusion with flag of Cusco

The Wiphala has been confused with the seven-striped rainbow design flag, the current official banner of the Peruvian city of Cusco, where it is commonly displayed in government buildings and in the main square.[16] This rainbow flag is sometimes displayed as a symbol of the Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu), although Peruvian historiographers and the Peruvian Congress have stated that the empire never had a flag.[17][18] While the wiphala is an emblem related principally to the Aymara people, the Inca had their origins with the Quechua people.

Others

-

Tupac Katari (alternate)

See also

References

- ^ "Bandera indígena boliviana es incluida como símbolo patrio en nueva Constitución", October 21, 2008, United Press International.

- ^ Republic of Bolivia, [Text of the proposed] Nueva Constitución Política del Estado, 2007.

- ^ "Carlotta – Objekt". Collections.smvk.se. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ^ Francisco López de Jerez, Verdadera relacion de la conquista del Peru y provincia de Cuzco, llamada la Nueva Castilla, 1534.

- ^ "... todos venían repartidos en sus escuadras con sus banderas y capitanes que los mandan, con tanto concierto como turcos".

- ^ ... el guión o estandarte real era una banderilla cuadrada y pequeña, de diez o doce palmos de ruedo, hecha de lienzo de algodón o de lana, iba puesta en el remate de una asta larga, tendida y tiesa, sin que ondease al aire, y en ella pintaba cada rey sus armas y divisas, porque cada uno las escogía diferentes, aunque las generales de los Incas eran el arco celeste."

- ^ Guaman Poma, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, (1615/1616), pp. 256, 286, 344, 346, 400, 434, 1077, this pagination corresponds to the Det Kongelige Bibliotek search engine pagination of the book. Additionally Poma shows both well drafted European flags and coats of arms on pp. 373, 515, 558, 1077. On pages 83, 167–171 Poma uses a European heraldic graphic convention, a shield, to place certain totems related to Inca leaders. There is no evidence of linear (Wiphala-like) patchwork.

- ^ "Emblema Nacional del Pusinsuyo = Tawantinsuyo" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-10-05.

- ^ "Wiphala | Ministerio de Defensa del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia". www.mindef.gob.bo. Archived from the original on 2022-03-19. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- ^ "Photos: Dassault Falcon 900EX Aircraft Pictures". Airliners.net. 2010-10-24. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ^ "Por decreto, el Ejecutivo fija dos fechas fechas de fundación del país". eju.tv. 2010-01-28. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ^ Prashad, Vijay (November 13, 2019). "A Bolivian crisis". The Hindu – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ "When the US Supports It, It's Not a Coup". Common Dreams.

- ^ "Jeanine Añez instruye que junto a la sagrada tricolor se mantenga la wiphala". eju.tv. 12 November 2019.

- ^ Inca empire#Organization of the empire

- ^ "revista.serindigena.cl – Wiphala, Símbolo de la Nación Andina". Archived from the original on 2007-08-10. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ "Bandera Gay o Bandera del Tahuantinsuyo Terra.com". Archived from the original on 2012-11-27. Retrieved 2015-08-21.

- ^ "La Bandera del Tahuantisuyo" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

External links

- Wiphala Emblems

- Emblema Nacional del Pusinsuyo = Tawantinsuyo

- History of Wiphala

- "Guaman Poma – El Primer Nueva Crónica Y Buen Gobierno" – A high-quality digital version of the Corónica, scanned from the original manuscript. Has numerous line drawings that illustrate both Inca flags and Spanish flags.