Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve

| Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve | |

|---|---|

Mount St. Elias, the second highest mountain of both the United States and Canada | |

The location of Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve within Alaska | |

| Location | Chugach Census Area, Copper River Census Area, Southeast Fairbanks Census Area and Yakutat City and Borough, Alaska, United States |

| Nearest city | Copper Center, Alaska |

| Coordinates | 61°26′06″N 142°57′13″W / 61.43500°N 142.95361°W |

| Area | 13,175,799 acres (53,320.57 km2) 8,323,147.59 acres (33,682.5833 km2) (Park only) 4,852,652.14 acres (19,637.9865 km2) (preserve only)[2] |

| Established | December 2, 1980 (park & preserve) December 1, 1978 (national monument) |

| Visitors | 79,450 (in 2018)[3] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | www |

| Part of | Kluane / Wrangell-St. Elias / Glacier Bay / Tatshenshini-Alsek |

| Criteria | Natural: (vii), (viii), (ix), (x) |

| Reference | 72ter |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Extensions | 1992, 1994 |

Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve is a United States national park and preserve in south central Alaska. The park, the largest in the United States, covers the Wrangell Mountains and a large portion of the Saint Elias Mountains, which include most of the highest peaks in the United States and Canada, yet are within 10 miles (16 km) of tidewater, one of the highest reliefs in the world. The park's high point is Mount Saint Elias at 18,008 feet (5,489 m), the second tallest mountain in both the United States and Canada. The park has been shaped by the competing forces of volcanism and glaciation, with its tall mountains uplifted by plate tectonics. Mount Wrangell and Mount Churchill are among major volcanos in these ranges. The park's glacial features include Malaspina Glacier, the largest piedmont glacier in North America, Hubbard Glacier, the longest tidewater glacier in Alaska, and Nabesna Glacier, the world's longest valley glacier. The Bagley Icefield covers much of the park's interior, which includes 60% of the permanently ice-covered terrain in Alaska. At the center of the park and preserve, the boomtown of Kennecott exploited one of the world's richest deposits of copper from 1903 to 1938. The abandoned mine buildings and mills comprise a National Historic Landmark district.

The park and preserve were established in 1980 by the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act,[4] following its designation as Wrangell–St. Elias National Monument on December 1, 1978, by President Jimmy Carter using the Antiquities Act, pending final legislation to resolve the allotment of public lands in Alaska. The protected areas are included in an International Biosphere Reserve and are part of the Kluane/Wrangell–St. Elias/Glacier Bay/Tatshenshini-Alsek UNESCO World Heritage Site, which includes the Canada's Kluane National Park and Reserve to the east and Glacier Bay National Park to the south.

The park and preserve form the largest area managed by the National Park Service with a total of 13,175,799.07 acres (20,587.19 sq mi; 53,320.57 km2), an expanse larger than nine U.S. states and around the same size as Croatia.[5] 8,323,147.59 acres (13,004.92 sq mi; 33,682.58 km2) are designated as the national park, and the remaining 4,852,652.14 acres (7,582.27 sq mi; 19,637.99 km2) are designated as the preserve; the chief distinction between park and preserve lands is that sport hunting is prohibited in the park and permitted in the preserve. The area designated as the national park alone is larger than the 47 smallest American national parks (out of 63) combined. In addition, about two-thirds of the park and preserve are designated as the largest single wilderness in the United States.

Park purpose

As stated in the foundation document:[6]

The purpose of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve is to maintain the natural scenic beauty of the diverse geologic, glacial, and riparian dominated landscapes, and to protect the attendant wildlife populations and their habitats; to ensure continued access for a wide range of wilderness-based recreational opportunities; to provide continued opportunities for subsistence use.

Geography

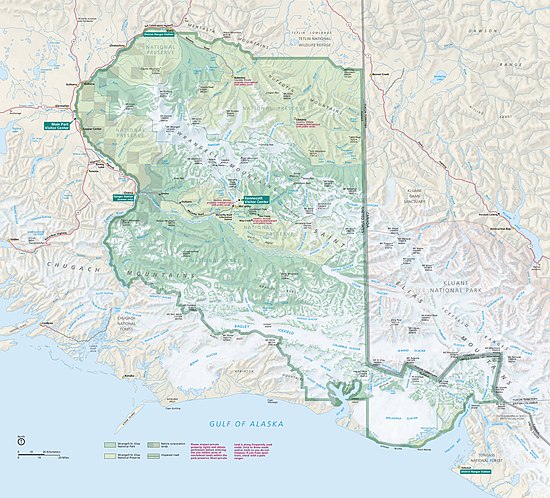

Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve includes the entire Wrangell range, the western portion of the Saint Elias Mountains and the eastern portion of the Chugach Mountains. Lesser ranges in the park or preserve include the Nutzotin Mountains, which are an extension of the Alaska Range, the Granite Range and the Robinson Mountains. Broad rivers run in glacial valleys between the ranges, including the Chitina River, Chisana River and the Nabesna River. All but the Chisana and Nabesna are tributaries to the Copper River, which flows along the western margin of the park and which has its headwaters within the park, at the Copper Glacier. The park includes dozens of glaciers and icefields. The Bagley Icefield covers portions of the St. Elias and Chugach ranges, and Malaspina Glacier covers most of the southeastern extension of the park, with Hubbard Glacier at the park's extreme eastern boundary, the largest tidewater glacier in North America.[7] The eastern boundary of the park is Alaska's border with Canada, where it is adjoined by Kluane National Park and Reserve.

On the southeast the park is bounded by Yakutat Bay, Tongass National Forest and the Gulf of Alaska. The remainder of the southern boundary follows the crest of the Chugach Mountains, adjoining Chugach National Forest. The western boundary is the Copper River, and the northern boundary follows the Mentasta Mountains and borders Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge.[8]

Mount St. Elias is situated on the border between Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Kluane National Park and Reserve. At 18,008 feet (5,489 m), it is the second-highest mountain in both Canada and the United States. Nine of the 16 highest peaks on U.S. soil are located in the park, along with North America's largest subpolar icefield, glaciers, rivers, an active volcano, and the historic Kennecott copper mines.[9] Both the St. Elias and Wrangell ranges have seen volcanic activity. The St. Elias volcanoes are considered extinct, but some of the volcanoes of the Wrangell Range have been active in Holocene time. Ten separate volcanoes have been documented in the western Wrangell Range, of which Mount Blackburn is the highest and Mount Wrangell is the most recently active.[10]

Nearly 66 percent of park and preserve land is designated as wilderness:[11] at 9,078,675 acres (3,674,009 ha), the Wrangell–St. Elias Wilderness is the largest designated wilderness in the United States.[4]

The park region is divided between national park lands, which only allow subsistence hunting by local rural residents, and preserve lands, which allow sport hunting by the general public. Preserve lands include the Chitina valley north of the river, two parts of the Copper River valley east of the river, most of the Chisana and Nabesna valleys, and lands along Yakutat Bay.[8]

The park is accessible by highway from Anchorage; two rough gravel roads (the McCarthy Road and the Nabesna Road) wind through the park which makes portions of the interior accessible for backcountry camping and hiking.[12] Chartered aircraft also fly into the park.[12] Wrangell–St. Elias received 79,450 visitors in 2018.[3] The park area includes a few small settlements. Nabesna and Chisana are in the northern part of the park. Kennicott and McCarthy are relatively close together in the center of the park, with a few smaller settlements nearby and along the 60-mile (97 km) McCarthy Road. Chitina serves as a gateway community where the McCarthy Road meets the Edgerton Highway along the Copper River. The McCarthy Road and the Nabesna Road are the only significant roads in the park.[8]

Activities

Access to the park is open all year, and most of the park facilities are open from May to September, although some locations open as late as the end of May and close in mid-August. The main visitor center remains open on weekdays in the winter.[13]

The Edgerton Highway runs along the valley of the Copper River on the western margin of the park. The headquarters and visitor center are at mile 106.8 near Copper Center. Road access to the park's interior is along the Nabesna Road and the McCarthy Road. The abandoned mining town of Kennecott can be accessed by footbridge from a continuation of the McCarthy road. Backcountry access is available by air taxi services.[14]

The Kendesnii campground on the Nabesna Road is the only Park Service-managed campground in the park. There are a number of private campgrounds and lodgings on the McCarthy and Nabesna roads, and there are fourteen public-use cabins. Most of these cabins are accessible only by air.[15] A few are accessible by road near the Slana Ranger Station, and most are associated with airstrips.[16] Backcountry camping is allowed without a permit. There are few established and maintained trails in the park.[17]

Mountain biking is mainly limited to roads due to prevailing boggy conditions in the summer.[18] On the other hand, float trips on the rivers are a popular way to see the park on the Copper, Nizina, Kennicott and Chitina rivers.[19] Because the park and preserve include some of the highest peaks in North America, they are a popular destination for mountain climbing. Of the 70 tallest mountains in Alaska, 35 are in the park, including seven of the top ten peaks.[20] Climbing these peaks is technically demanding, and requires expeditions to access remote and dangerous terrain.[21]

In addition to the Copper Center visitor center, the park maintains a visitor center at Kennecott and an information station at Mile 59 on the McCarthy Road. There are ranger stations at Slana on the Nabesna Road, in Chitina at the end of the Edgerton Highway, and in Yakutat.[22] The Yakutat ranger station is shared with Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve.[23] The park has three improved airstrips, at McCarthy, May Creek and Chisana, with a number of unimproved strips scattered around the park.[24] Air taxis provide sightseeing services and visitor transportation within the park, based in Glennallen, Chitina, Nabesna, and McCarthy.[25] Air taxis provide access to sea kayak tours that operate in the vicinity of Icy Bay.[26] Farther east on the park's coast, cruise ships are frequent visitors to Hubbard Glacier in Yakutat Bay.[27]

Sport hunting and trapping are allowed only within the preserve lands. Subsistence hunting by local residents is permitted in both the park and preserve. Hunting is managed jointly by the National Park Service, and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, which issues hunting licenses. The use of off-road vehicles (ORVs) is restricted to specific routes and permits are required to use ORVs in the preserve.[28]

Geology

The southern part of Alaska is composed of a series of terranes that have been pushed against the North American landmass by the action of plate tectonics. The Pacific Plate moves northwestward relative to the North American Plate at about 2 inches (5.1 cm) to 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) per year,[29] meeting the continental landmass in the Gulf of Alaska. The Pacific Plate subducts under the Alaskan landmass, compressing the continental rocks and giving rise to a series of mountain ranges. Terranes or island arcs carried on the surface of the Pacific Plate are carried against the Alaskan landmass and are themselves compressed and folded, but are not fully carried into the Earth's interior. As a result, a series of terranes, collectively known as the Wrangellia composite terrane, have been pushed against the south coast of Alaska, followed by the Southern Margin composite terrane to the south of the Border Ranges fault system.[30] A byproduct of the subduction process is the formation of volcanoes at some distance inland from the subduction zone.[31] At present the Yakutat Terrane is being pushed under material of similar density, resulting in uplift and a combination of accretion and subduction. Nearly all of Alaska is composed of a series of terranes that have been pushed against North America.[32] The coastal region is seismically active with frequent large earthquakes. Major quakes occurred in 1899 (four between magnitudes 7 and 8) and 1958 (7.7), followed by the 1964 Alaska earthquake (9.2). The 1979 St. Elias earthquake reached magnitude 7.9.[33][34]

Six terranes and one sedimentary belt have been documented in Wrangell–St. Elias. From north to south, and oldest to youngest, they are the Windy or Yukon-Tanana (180 million years ago), Gravina-Nutzotin Belt (120 MYa), Wrangellia, Alexander, Chugach (previously assembled elsewhere, then accreted as the Wrangellia composite terrane 110-67 MYa), Prince William (50MYa) and Yakutat terranes (beginning 26 MYa).[35] The Wrangellian rocks include fossiliferous sedimentary rocks interspersed with volcanic rocks.[36]

The Alaskan coast reached an approximation of its modern configuration about 50 million years ago, with the complete subduction of the now-vanished Kula Plate under North America.[33] The present subduction of the Pacific Plate in southern Alaska has been going on for about 26 million years. The oldest volcanoes in Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve are about 26 million years old, near the Alaska-Yukon Territory border in the St. Elias Range. Activity has moved north and west from that area.[10]

Volcanic activity

The majority of the volcanoes in the Wrangell volcanic field lie at the western end of the Wrangell Mountains. The western Wrangell volcanoes are unusual for subduction-related volcanoes, in their generally non-explosive nature. The majority of the volcanoes are unusually large shield volcanoes that built to their present size quickly from voluminous flows of andesite lavas which erupted from multiple centers.[37] Their growth is associated with the arrival of the Yakutat terrane, with considerable activity until about 200,000 years ago, when movement along the Denali-Totchunda and Fairweather faults began to accommodate some of the Pacific Plate's motion. For that reason, very large magmatic flows are regarded as unlikely in the present day. The majority of the Wrangell volcanoes are shield volcanoes with large collapse calderas at their summits. All but Mount Wrangell have been modified by glaciers to sharper, steeper relief than the gentle, rounded forms that characterize young shield volcanoes. The shield volcanoes are surrounded by cinder cones that formed after the main volcano.[38]

The ten highest summits in the Wrangell Mountains are all of volcanic origin, and several are among the most voluminous volcanoes in the world. Mount Wrangell is the only Wrangell volcano considered active.[38] Wrangell measures 14,163 feet (4,317 m) in height. It was built by a series of large lava flows from 600,000 to 200,000 years ago. Three comparatively modest eruptive episodes were reported in 1784, 1884–85 and 1900. The gently sloping dome features an ice-filled summit caldera measuring 3.6 miles (5.8 km) by 2.5 miles (4.0 km). Three craters containing fumaroles produce a steam plume that can be visible on calm, clear days. The summit produces occasional phreatic eruptions that can coat the ice with ash. During the 1980s the summit's heat flux was sufficient to melt 100 million cubic metres (3.5×109 cu ft) of ice and form a small crater lake. That activity has subsided since 1986 and ice has accumulated since. The last large eruption of magma from Wrangell is estimated to have been about 50,000 to 100,000 years ago. The summit caldera is estimated to have collapsed between 200,000 and 50,000 years ago. 13,009-foot (3,965 m) Mount Zanetti is a large cinder cone on Wrangell's northwest flank, estimated to be less than 25,000 years old.[39][40]

Mount Drum is the westernmost Wrangell volcano. 12,010 feet (3,660 m) high, it dominates the local landscape more than much higher mountains. Mount Drum is either a shield volcano or a stratovolcano that has been extensively eroded by glacial activity, preceded by explosive activity about 250,000–150,000 years ago that destroyed a summit that may have once measured 14,000 to 16,000 feet (4,300 to 4,900 m). These eruptions generated extensive mudflows, and represent the last activity at Mount Drum. Mount Drum supports at least eleven glaciers that flow from its summit icefield.[41]

Mount Sanford is the tallest of the western Wrangell volcanoes at 16,237 feet (4,949 m), the 13th highest peak in North America. It is a complex shield volcano that first formed about 900,000 years ago. The latest eruption is estimated to have been between 320,000 and 100,000 years ago. Like Drum, Sanford has a large icefield above 8,000 feet (2,400 m) that feeds a series of glaciers.[42] Capital Mountain is located near Mount Sanford, but is much smaller at 7,731 feet (2,356 m) in height. It is a shield volcano, about 10 miles (16 km) in diameter. Its summit has collapsed to form a caldera roughly 2.5 miles (4.0 km) in diameter. Its last activity was about a million years ago, and it has been deeply eroded by glacial activity.[43] Tanada Peak is an older and larger neighbor of Capital Mountain, 9,358 feet (2,852 m) tall with a 4-mile (6.4 km) by 5-mile (8.0 km) summit caldera. The shield volcano last erupted 900,000 years ago and has been dissected by glaciers.[44] The Skookum Creek Volcano is a volcanic center that has been heavily eroded. It was active between 3.2 million and 2 million years ago. 7,125 feet (2,172 m) high at its highest point, the old shield volcano has been severely eroded. Its caldera is surrounded by a series of dacite and rhyolite domes. Mount Jarvis is a shield volcano. 13,421 feet (4,091 m) high, with one or more indistinct summit calderas. It is covered with ice and erupted between 1.7 million and 1 million years ago.[45] Mount Blackburn is at 16,390 feet (5,000 m) the highest point in the Wrangells, the 12th highest peak in North America, and the oldest volcano in the range. It is a shield volcano with a filled caldera that was active between 4.2 million and 3.4 million years ago. Mount Blackburn is ice-covered and is the source of Kennicott Glacier and Nabesna Glacier, among others.[45] The Boomerang volcano is a very small shield volcano, only rising 3,949 feet (1,204 m). It is at least one million years old and is overlaid by deposits from Capital Mountain.[46] Mount Gordon is a cinder cone, one of the largest in the Wrangells at 9,040 feet (2,760 m).[47]

Several hot springs or mud volcanoes in the vicinity of Mount Drum produce warm brackish water charged with carbon dioxide. The largest are called Shrub, Upper Klawasi and Lower Klawasi. Their deposits of hydrothermally-altered mud have built cones 150 to 300 feet (46 to 91 m) high and 8,000 feet (2,400 m) in diameter.[40][48]

The chief volcanoes in the St. Elias Range are Mount Bona and Mount Churchill. At 16,421 feet (5,005 m) and 15,638 feet (4,766 m), respectively, they are the highest and fourth-highest volcanoes in the United States and the fourth and seventh highest in North America,[49] and Bona is the tenth highest peak of any kind in North America. Churchill is often regarded as a subsidiary peak of Bona.[49] Both are ice-covered stratovolcanoes. Churchill is the source of the White River Ash. It erupted about 100 AD and 700 AD, spreading ash across much of Alaska and northwestern Canada.[40][49]

Glaciers and icefields

The mountain ranges of Wrangell–St. Elias account for 60 percent of glacial ice in Alaska, covering more than 1,700 square miles (4,400 km2). The glaciers have advanced and retreated repeatedly, reaching the sea and filling the valley of the Copper River. A glacial dam in the valley retained Lake Atna during the Wisconsin glaciation. Drainage of the lake has scoured the riverbed to bedrock above the Bremner River.[50] Several features are particularly notable. The Malaspina Glacier is the largest piedmont glacier in North America, Hubbard Glacier is at 75 miles (121 km) the longest tidewater glacier in Alaska, and the Nabesna Glacier is the world's longest valley glacier, at more than 53 miles (85 km).[51]

Glaciers in Wrangell–St. Elias are mostly in retreat. The Bagley Icefield has grown thinner and its glaciers have retreated, including portions feeding Malaspina Glacier, which is stagnant or retreating. Malaspina's west and east lobes filled Icy Bay and Yakutat Bay, respectively, about 1000 years ago, and Guyot, Yahtse and Tyndall Glaciers have individually retreated at the head of Icy Bay.[52] However, Hubbard Glacier advanced from 1894, closing Russell Fjord.[53][54]

Minerals

Five major mining districts were developed in Wrangell–St. Elias during the heyday of mining between the 1890s and 1960. Gold was found in the Bremner district in 1901, and in the Nizina area near Kennecott. Most of the gold from these areas was placer gold, obtained through hydraulic mining. Copper nuggets were found with the gold and were usually discarded as uneconomical to ship until roads were improved to the area. Other gold strikes were made in the Chisana district, with a minor stampede between 1913 and 1917 to the area by miners. During the 1930s lode ore was mined in the Nabesna district.[55]

The chief source of copper was the Kennecott lode next to the Kennicott Glacier. The copper sulfide ore assayed at 70% copper when first discovered, among the richest ever found. Total production amounted to more than 536,000 metric tons of copper and about 100 metric tons of silver. After the chalcocite ore was exhausted the mines worked malachite and azurite deposits embedded in hydrothermally-altered dolomite.[56] The copper is believed to have been dissolved in hot water moving through copper-rich Nikolai Greenstone, then redeposited in concentrated form in Chitistone Limestone through reaction with sulfide-rich waters in the limestone.[57] A number of other sites on the southern side of the Wrangells were investigated and prospected, and some even produced small amounts of ore, but none were commercially exploited.[58] Large, but low-grade deposits of nickel and molybdenum were investigated as late as the 1970s.[59]

History

Early history and exploration

Archeological evidence indicates that humans entered the Wrangell Mountains about 1000 AD. The Ahtna people settled in small groups along the course of the Copper River. A few Upper Tanana speakers settled along the Nabesna and Chisana Rivers. The Eyak people settled near the mouth of the Copper River on the Gulf of Alaska. Along the coast the Tlingit people dispersed, with some settling at Yakutat Bay.[60] The first Europeans in the area were Russian explorers and traders. Vitus Bering landed in the area in 1741. Fur traders followed. A permanent Russian trading post was established in 1793 by the Lebedev-Lastochkin Company at Port Etches on Hinchinbrook Island near the mouth of the Copper River. A competing post operated by the Shelikov Company was established in 1796 at Yakutat Bay. The Shelikov Company sent Dmitri Tarkhanov to explore the lower Copper River and to look for copper deposits, inspired by reports that the native peoples used implements and points made of pure copper.[61] Another exploration party in 1797 was killed by natives. Semyen Potochkin was more successful in 1798, reaching the mouth of the Chitina River and spending the winter with the Ahtna. In 1799 Konstantin Galaktionov reached the Tazlina River, but was wounded in an attack by the Ahtna. He was killed on a return trip in 1803. The Tlingit and Eyak attacked and destroyed the Russian post at Yakutat in 1805. It was not until 1819 that a party under Afanasii Klimovskii was sent to explore the Copper River again, reaching the upper portion of the river and establishing the Copper Fort trading post near Taral. A party that started from Taral in 1848 with the intention of reaching the Yukon River was killed by the Ahtna, ending Russian exploration.[62]

American interest in the area after Alaska's acquisition by the United States in 1867 was limited until gold was found in the Yukon Territory in the 1880s. George Holt was the first American known to have explored the lower Copper River, in 1882. In 1884 John Bremner prospected the lower river. The same year a U.S. Army party led by Lieutenant William Abercrombie attempted to explore the lower river, and found a passage to the country's interior over a glacier at the Valdez Arm. In 1885 Lieutenant Henry Tureman Allen fully explored the Copper and Chitina rivers, going on to cross the Alaska Range and enter the Yukon River system and eventually reaching the Bering Sea.[63] The Allen expedition also noted the use of copper by native peoples along the Copper River.[64] Several other expeditions explored the coastal regions in the late 1880s, and some attempted to climb the mountains. An 1891 expedition led by Yukon explorer Frederick Schwatka descended the Nizina, Chitina and Copper Rivers from the north.[65]

Mineral extraction

The discovery of gold in the Canadian Klondike brought prospectors to the region who discovered some gold along the Copper River. Explorers' reports of copper tools and copper nuggets caused the U.S. Geological Survey to send a geologist, Oscar Rohn, to look for the source. Rohn reported finding copper ore in Kennicott Glacier, but did not find the source. Shortly afterwards prospectors Jack Smith and Clarence Warner are said to have noticed a green spot on a hillside at what is now Kennecott, which proved to be a rich copper lode. Engineer Stephen Birch acquired the rights to the deposit and established the Alaska Copper and Coal Company in 1903 to mine it. Birch obtained cash from investors like J. P. Morgan and the Guggenheim family, who became known as the "Alaska Syndicate" and his venture became Kennecott Mines in 1906, eventually becoming the Kennecott Copper Corporation. The town was named after the glacier, but misspelled, so that "Kennicott" became "Kennecott."[66] Other copper deposits were found on the south side of the Wrangells at Bremner and Nizina. Smaller deposits of both gold and copper were found in the Nabesna area.[67]

Development of the remote site required the construction of a railway 195 miles (314 km) long and costing $23.5 million at the time of its construction. The Copper River and Northwestern Railway (CR&NW) took five years to build, extending to Cordova on the coast. The towns of Chitina and McCarthy grew up on the line. The Kennecott mine employed surface mining, underground galleries, and, uniquely, mining in glacial ice to recover ore that had been scraped off the surface deposit by the Kennicott Glacier encased in ice.[68]

By the 1920s the highest-grade ore had been exhausted and the decline extended into the 1930s, until the Kennecott operation was finally shut down in 1938 after extracting over 4.5 million tons of ore, which yielded 600,000 tons of copper and 562,500 pounds (255,100 kg) of silver with a net profit of $100 million to the investors.[69]

Reports of oil and gas seeps in the vicinity of Cape Yakutaga and Controller Bay inspired petroleum exploration on the southern margin along the Gulf of Alaska. A small oilfield at Katalla produced oil from 1903 to 1933, when its refinery was destroyed by fire. The petroleum deposits were instrumental in the exclusion of the coast from Icy Bay to the Copper River delta from the future park. Coal seams were also noted near Kushtaka Lake.[70] A boom took place from 1974 to 1977 with the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System near the western margin of the future park. The boom was short-lived, and local residents returned to trapping, fishing and guiding hunters for their living.[71] Thirteen test wells were drilled offshore in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[70]

National park proposals

The first proposals for protected lands in the region came from the newly established U.S. Forest Service in 1908, but were not pursued.[72] Early studies of possible new Park Service units in Alaska took place in the 1930s and 1940s. The first study, entitled Alaska — Its Resources and Development was centered on the development of tourism in existing parks such as Denali (then called Mount McKinley National Park), despite a dissent from co-author Bob Marshall, who advocated strict preservation.[73] In 1939 Ernest Gruening, then Director of the Division of Territories and Island Possessions in the Department of the Interior and later governor of the Alaska Territory, proposed the establishment of a park in the Chitina Valley, to be called Panorama National Park or Alaska Regional National Park, together with Kennicott National Monument, a 900-square-mile (2,300 km2) area that was to include Kennicott Glacier and the Kennecott mine site.[72] Gruening was supported by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt declined to act, noting that there was no urgency, and citing his directive that all non-defense related measures be deferred to preparations for the looming World War II.[74]

A lukewarm assessment by Mount McKinley superintendent Frank Been in 1941 further diminished enthusiasm. However, Canada proposed a St. Elias Mountains International Park for the region in 1942, and established the Kluane Game Sanctuary in 1943 on its side of the border, which would eventually become Kluane National Park. These actions inspired the Interior Department to discuss a corresponding system of parks on the Alaska side, which would include what was then Glacier Bay National Monument, portions of the Wrangell and Chugach Mountains, and Malaspina and Bering Glaciers.[75]

In 1964, George B. Hartzog Jr., director of the National Park Service, initiated a new study entitled Operation Great Land, advocating the development and promotion of the existing Alaska parks.[73] Gruening, by then one of Alaska's senators, proposed a "National Park Highway" for the region in 1966.[75] Further action by the Park Service in the late 1960s resulted in a master plan and draft legislation. By 1969 Interior's Bureau of Outdoor Recreation proposed that the Bureau of Land Management oversee a 10.5-million-acre (42,000 km2) Wrangell Mountain Scenic Area. This management scheme was proposed to allow resource development in addition to preservation and recreation. Park Service reaction was hostile, but Secretary of the Interior and former Alaska governor Walter J. Hickel supported the idea. Despite the effort to preserve the possibility of resource development, Hickel's successor as governor, Keith Harvey Miller, opposed the proposed National Scenic Area on the grounds that it would pre-empt potential Alaska state land claims in the area.[76]

The 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) spurred new proposals for Alaska parks. As part of the process of divesting federal lands to the state of Alaska and to native corporations, the act required the withdrawal of 80 million acres (320,000 km2) of lands for conservation. The National Park Service responded with a proposal for a 15,000,000-acre (6,100,000 ha) Alaska National Park in the Wrangell Mountains region. Hickel's successor as Interior secretary Rogers Morton cut the proposed area to 9.3 million acres (3,800,000 ha), withdrawing the western Wrangell Mountains and excluding Mount Wrangell itself and Mount Sanford. Later amendments brought the proposed acreage back to 13.4 million acres (54,000 km2). A scaled-back park of 8,640,000 acres (3,500,000 ha) was proposed by Interior in 1973, together with a 5.5-million-acre (22,000 km2) Wrangell Mountain National Forest, getting a cold reception from both preservationists and developers. Competing bills were drafted during 1974 by both preservation and development interests with little advancement. In the same year the Park Service and Forest Service started a joint study for the Wrangell area and cooperated in glacier studies and in architectural surveys of the Kennecott mills.[77]

A variety of bills were introduced in Congress in 1976 with widely varying proposed acreage and levels of protection. None succeeded, but one bill proposed by conservation-oriented groups introduced the concept of national preserves, which would enjoy most of the protections associated with national parks, but which would allow hunting. In 1977 Representative Morris K. Udall introduced the first version of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) as H.R. 39, in which a 14-million-acre (57,000 km2) Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and a 1.8-million-acre (7,300 km2) Chisana National Preserve were proposed. Although supported by the Park Service, the bill was opposed by Alaska. A revised bill was proposed by the Interior Department, with 9.6 million acres (3,900,000 ha) in national park lands and 2.49 million acres (10,100 km2) in an adjoining preserve, both to be named Wrangell–St. Elias. Hearings in 1978 adjusted the areas, boundaries and relative proportions of park and preserve lands, with a view to allowing the hunting of Dall sheep in the Wrangell Mountains, and introducing a National Recreation Area to the north of the mountains.[78]

Alaska senator Mike Gravel threatened to filibuster the proposed ANILCA bill, effectively killing it. Following this blockage and with efforts on the part of Alaska authorities to claim lands that fell within the proposed protections, President Jimmy Carter invoked the Antiquities Act to proclaim 17 Alaskan national monuments, including 10,950,000 acres (4,430,000 ha) in Wrangell–St. Elias National Monument on December 1, 1978.[79][80]

The monument designation carried no dedicated funding for park development or operations, but did engender considerable hostility from Alaskans, who regarded the designation under the Antiquities Act as a federal land grab. The few Park Service personnel assigned to the area received threats, and a Park Service airplane was destroyed by fire in August 1979. Attitudes were sharply divided between white Alaskans, who were largely opposed to the park and felt that they were being forced out, and native Ahtnas, who were granted subsistence hunting rights and who expected to profit from tourism.[81]

National park and preserve

In January 1979, Udall introduced a modified version of H.R. 39. Following markup and negotiations between the House and Senate versions, the bill as modified by the Senate was approved by the House on November 12.[82] On December 2, 1980, the ANILCA bill was signed into law by Jimmy Carter, converting Wrangell–St. Elias to a national park and preserve with an initial area of 8,147,000 acres (3,297,000 ha) in the park and 4,171,000 acres (1,688,000 ha) in the preserve.[83] Boundaries between the park and preserve areas were drawn according to perceived values of scenery versus hunting potential In accordance with the legislation, the designated areas included 9,660,000 acres (3,910,000 ha) of wilderness, stipulated in a somewhat less restrictive manner than standard practice in the continental United States.[84]

Opposition to the park persisted after Congressional designation from some Alaskans, who resented federal government presence in general and National Park Service presence in particular. Vandalism persisted, with a ranger cabin burned and an airplane damaged, while others skirted regulations and voiced resentment of what, in their view, was an elitist attitude embodied in the park and the Park Service.[85] However, relations improved for a time, with local businesses promoting the park and working with the Park Service on tourism projects. Incidents continued, notably involving arson at a ranger station, and relations bottomed again in 1994 when the park superintendent Karen Wade testified before Congress for increased funding in a way that was perceived to confirm residents' suspicions about the Park Service, exacerbated by commentary from local newspapers that was wrongly attributed to Wade. This marked the high point of resentment against the park, as local residents began to take part in Park Service sponsored events.[86] Nevertheless, the 1979 designation of the region as a UNESCO World Heritage Site continued to be seen with suspicion. The John Birch Society claimed that the designation was part of a United Nations plan to assume control of the U.S. national park system.[87]

The state of Alaska proposed major improvements to the McCarthy Road in 1997, planning to pave it and add scenic turnouts and trailheads along its length[citation needed]. Although the road remains gravel, it has been widened and smoothed. Some rental car agencies continue to prohibit use of their vehicles on the McCarthy Road.[88]

Additional designations

The transborder park system Kluane / Wrangell–St. Elias / Glacier Bay / Tatshenshini-Alsek (comprising Wrangell–St. Elias and three other national and provincial parks) was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979 for the spectacular glacier and icefield landscapes as well as for the importance of grizzly bears, caribou and Dall sheep habitat.[4] 9,078,675 acres (3,674,009 ha) of the park and preserve were designated as the Wrangell–Saint Elias Wilderness upon the park's establishment in 1980,[89] the largest single wilderness area in the United States.[90]

Climate

The climate of the park's interior is dominated by long, cold winters in which temperatures may remain below freezing for five months. Nighttime low temperatures can sink to −50 °F (−46 °C) and daytime highs of 5 °F (−15 °C) to 7 °F (−14 °C) are usual. Summer lasts two months, June and July, bringing flowers and biting insects, with maximum temperatures of 80 °F (27 °C). Late summers can bring drizzle. It begins to get cool in August, and first snows fall in September. Conditions are more temperate along the coast, and the high mountains retain snow all year.[91]

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve encompasses the following three types;

1) Continental Subarctic - Cold Dry Summer (Dsc). Dsc climates are characterized by their coldest month averaging below 0 °C (32 °F), 1–3 months averaging above 10 °C (50 °F), at least three times as much precipitation in the wettest month of winter as in the driest month of summer, and driest month of summer receives less than 30 mm (1.2 in).

2) Subarctic With Cool Summers And Dry Winters (Dwc). Dwc climates are characterized by their coldest month averaging below 0 °C (32 °F), 1–3 months averaging above 10 °C (50 °F), and 70% or more of average annual precipitation received in the warmest six months.

3) Subarctic With Cool Summers And Year Around Rainfall (Dfc). Dfc climates are characterized by their coldest month averaging below 0 °C (32 °F), 1–3 months averaging above 10 °C (50 °F), and no significant precipitation difference between seasons.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the Plant Hardiness zone at the Kennecott Visitor Center (1985 ft / 605 m) is 3a with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of -37.8 °F (-38.8 °C).[92]

| Climate data for McCarthy, Alaska, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1984–2017 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 44 (7) |

54 (12) |

56 (13) |

71 (22) |

86 (30) |

90 (32) |

90 (32) |

86 (30) |

72 (22) |

75 (24) |

58 (14) |

56 (13) |

90 (32) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 6.0 (−14.4) |

20.7 (−6.3) |

32.9 (0.5) |

47.7 (8.7) |

62.2 (16.8) |

69.7 (20.9) |

71.4 (21.9) |

66.8 (19.3) |

55.5 (13.1) |

38.6 (3.7) |

17.3 (−8.2) |

9.2 (−12.7) |

41.5 (5.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | −1.6 (−18.7) |

9.7 (−12.4) |

18.2 (−7.7) |

34.6 (1.4) |

46.6 (8.1) |

54.3 (12.4) |

57.3 (14.1) |

53.5 (11.9) |

44.3 (6.8) |

29.4 (−1.4) |

9.7 (−12.4) |

2.3 (−16.5) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | −9.1 (−22.8) |

−1.3 (−18.5) |

3.5 (−15.8) |

21.6 (−5.8) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

38.9 (3.8) |

43.3 (6.3) |

40.2 (4.6) |

33.1 (0.6) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

2.0 (−16.7) |

−4.5 (−20.3) |

18.2 (−7.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −55 (−48) |

−49 (−45) |

−41 (−41) |

−21 (−29) |

−1 (−18) |

24 (−4) |

28 (−2) |

18 (−8) |

6 (−14) |

−22 (−30) |

−46 (−43) |

−50 (−46) |

−55 (−48) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.93 (24) |

1.11 (28) |

0.40 (10) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.93 (24) |

1.63 (41) |

2.45 (62) |

2.65 (67) |

2.56 (65) |

2.22 (56) |

1.45 (37) |

1.06 (27) |

17.70 (450) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 13.2 (34) |

7.9 (20) |

5.4 (14) |

2.5 (6.4) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.7 (6.9) |

9.4 (24) |

13.5 (34) |

11.3 (29) |

66.5 (169) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.7 | 7.1 | 4.7 | 2.8 | 7.0 | 11.3 | 14.0 | 16.4 | 15.4 | 11.2 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 118.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.8 | 6.6 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 5.2 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 46.7 |

| Source 1: NOAA[93] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: WRCC (extremes)[94] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

As the park and preserve cover an area larger than Switzerland, extending from the Gulf of Alaska to the Alaskan interior, with altitudes that vary from sea level to 19,000 feet (5,800 m), Wrangell–St. Elias has a wide variety of habitats. Much of the park is high mountain peaks covered with permanent ice, glaciers and icefields. Rivers occupy broad, flat glacial valleys and have constantly-changing braided riverbeds.[95] The environment can be divided into five major categories, apart from the relatively sterile glacial and riverbed areas: lowlands, wetlands, uplands, sub-alpine and alpine. Some of these environments are influenced and defined by the presence of permafrost, permanently frozen sub-soil.[96]

Plant communities

The lowland regions of the park border the Gulf of Alaska as well as the lower levels of the river valleys. Black spruce dominates areas of permafrost, with understories of alder, Labrador tea, willows and blueberry, with a variety of ground mosses.[96]

Wetlands can occur along the coast as well as the interior river basins. Permafrost regions are often marshy regions of muskeg. The wetland areas are primarily grassy, with sedges and small shrubs. Horsetails such as Equisetum palustre and spikerush are also found.[96]

The drier forested upland portions of the park are mostly interior boreal forest, or taiga. The distribution of tree species is determined by fire frequency and extent. The most abundant conifers in the forest are Black spruce and larger white spruce, with white spruce more prevalent in areas without permafrost. Black spruce are better adapted to fire conditions. Both quaking aspen and paper birch are common deciduous species that are among the first trees to grow following a fire.[97] They are followed by balsam poplar and eventually white spruce.[96]

Subalpine environments occur above the local tree line, which in Wrangell–St. Elias usually varies from 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) to 1,700 metres (5,600 ft). Plants are low and slow-growing shrubs, mainly graminoids and forbs.[96]

The alpine environment is variable according to the availability of water. It starts at a variable altitude from 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) in dry areas to 1,400 to 1,800 metres (4,600 to 5,900 ft) in wetter areas. Heaths and low-growing willows are common, along with forbs.[96]

Wildlife

Large, terrestrial mammals include the timber wolf, grizzly bear, black bear, and Mentasta and Chisana herds of caribou. Cougar (mountain lions) are considered possible, as the park may constitute the northernmost extent of their range, but none have been officially documented. Mountain goats, and roughly 13k Dall sheep—one of the densest populations on the continent—are found in the remote, montane areas. Moose, while not abundantly common in the region, may sometimes be observed in areas of dense willow growth.[98] A few Canadian wood bison have been established in two herds within the park, mostly in the Copper and Chitina River valleys.

The smaller mammals include the wolverine, North American beaver, Canadian lynx, porcupine, pine marten, river otters, red fox, some coyote, Arctic ground and flying squirrels, hoary marmot, weasels, ermine, snowshoe hare, several species of voles and mice, and pikas.[99] The waters along the coast host many migrating whales (including orcas, humpback and gray whales), resident Dall’s and harbor porpoises, harbor seals and California sea lions. The larger (and endangered) Steller sea lion may also be observed along the park’s coastal waters, in addition to the rare and over-hunted Alaskan sea otter.[100]

Twenty-one species of fish have been documented in fresh waters in the park. Differences in fish distribution depend on drainage: northern pike are not seen in the Copper River drainages, and no salmon species are seen in Yukon River drainages.[101] Large freshwater fish include Chinook, chum, coho, pink and sockeye salmon, as well as other salmonids such as lake trout, cutthroat trout, Dolly Varden, Arctic grayling and rainbow trout. Other fish include eulachon, burbot, round whitefish, northern pike, Pacific lamprey, lake chub and a variety of sculpins.[102]

About 93 species of birds inhabit Wrangell–St. Elias, though only 24 remain during the harsh winter. The most common birds include bald eagle, willow and rock ptarmigan, Canada jays, ravens, hermit thrushes, American robins, lesser yellowlegs, wandering tattler, hairy woodpeckers and northern flickers. Owls include the great horned, great gray, northern hawk and boreal owls.[103] Waterfowl includes trumpeter swan, common loon, northern pintail, mallards, and green-winged teal.

See also

- List of national parks of the United States

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve

References

- ^ "Protected Area Profile for Wrangell-St. Elias from the World Database of Protected Areas". protectedplanet.net. UN World Conservation Monitoring Centre and the IUCN. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ "Listing of acreage – December 31, 2011" (XLSX). Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved March 8, 2012. (National Park Service Acreage Reports)

- ^ a b "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Wrangell-St. Elias 2011 Foundation Statement" (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 6, 16–17, 20–38. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ Hetter, Katia (August 25, 2016). "Highest, tallest, hottest: National park record-setters". CNN Travel. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ "Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve FOUNDATION STATEMENT" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Winkler, p. xi.

- ^ a b c "Wrangell-St. Elias National Park Map". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Wrangell St. Elias National Park & Preserve". National Parks Conservation Association. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Richter et al, pp. 8–10.

- ^ "The National Parks: Index 2009–2011". National Park Service. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ a b "Wrangell-Saint Elias: Directions". National Park Service. December 2, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ "Operating Hours and Seasons". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Things to do". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Camping & Lodging". Wrangell-St' Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Backcountry Cabins". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Hiking & Backpacking". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Mountain Biking". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "River Trips". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Highest Alaskan Summits". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Mountaineering". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Visitor Centers". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Yakutat Ranger Station". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Backcountry Airstrips and Cabins". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Flightseeing & Air Taxis". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Sea Kayaking in Icy Bay". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Choosing the Right Cruise for You". Frommer's Alaska. John Wiley and Sons. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Sport Hunting". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Winkler, p. 12.

- ^ Winkler, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Richter et al, pp. 3–7.

- ^ Winkler, p. 19.

- ^ a b Winkler, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Winkler, p. 69.

- ^ Winkler, p. 20.

- ^ Winkler, p. 40.

- ^ Winkler, p. 76.

- ^ a b Richter et al, pp. 7–12.

- ^ Richter et al, pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b c Winkler, p. 110.

- ^ Richter et al, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Richter et al, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Richter et al, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Richter et al, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Richter et al, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Richter et al, p. 25.

- ^ Richter et al, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Richter et al., p. 29.

- ^ a b c Richter et al, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Winkler, pp. 78, 81.

- ^ "Glaciers". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Winkler, pp. 80–83.

- ^ Winkler, p. 85.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 167–169.

- ^ Winkler, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Winkler, p. 90.

- ^ Winkler, p. 92.

- ^ Winkler, p. 94.

- ^ Winkler, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Winkler, p. 4.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Richter et al, p. 1.

- ^ Winkler, p. 5.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Winkler, p. 7.

- ^ Winkler, p. i.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Winkler, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Bleakley, p. 8.

- ^ a b Bleakley, p. 11.

- ^ a b Catton, Theodore. "A Fragile Beauty: An Administrative History of Kenai Fjords National Park" (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 25–27. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ Bleakley, p. 12.

- ^ a b Bleakley, p. 13.

- ^ Bleakley, p. 14.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 14–18.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Bleakley, p. 21.

- ^ Catton, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Bleakley, p. 27.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Bleakley, pp. 43–47.

- ^ Bleakley, p. 48.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ^ "The National Wilderness Preservation System". National Atlas of the United States. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Creation and Growth of the National Wilderness Preservation System". Wilderness.net. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Weather". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "MCCARTHY 3 SW, ALASKA (505757)". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Rivers and Streams". Wrangell-St, Elias National Park. Nationalwde124511235ervice. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Plant Communities of Wrangell-St. Elias". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Common Trees". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Simeone, William E. (August 2006). "Some Ethnographi and Historical Information on the Use of Large Land Mammals in the Copper River Basin" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Mammal List" (PDF). Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. 2003. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Mammals". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Fish". Wrangell-St. Elias National ark. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Freshwater Fishes" (PDF). Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Birds". Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

Bibliography

- Bleakley, Geoffrey T. (2002). Contested Ground: Administrative History of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve 1978–2001 (PDF). National Park Service.

- Eppinger, R. G., et al. (2000). Environmental geochemical studies of selected mineral deposits in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1619. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Richter, Donald H. Rosenkrans, Danny S.; Steigerwald, Margaret J. (1995). Guide to the Volcanoes of the Western Wrangell Mountains, Alaska—Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2072. Denver: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Winkler, G. R. (2000). A Geologic Guide to Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska : A Tectonic Collage of Northbound Terranes (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1616. Denver: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

External links

- Official website

of the National Park Service

of the National Park Service - Alaskan national parklands – National Park Service

- Wilderness.net: Wrangell–Saint Elias Wilderness

- World Heritage Site

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) documentation, filed under McCarthy, Valdez-Cordova Census Area, AK:

- HAER No. AK-9, "Green Butte Copper Company", 6 photos, 1 color transparency, 2 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. AK-9-A, "Green Butte Copper Company, Manager's House", 2 photos, 1 data page, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. AK-9-B, "Green Butte Copper Company, Bathhouse", 1 photo, 1 data page, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. AK-9-C, "Green Butte Copper Company, Bunkhouse", 3 photos, 1 data page, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. AK-9-D, "Green Butte Copper Company, Stables", 8 photos, 1 data page, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. AK-9-E, "Green Butte Copper Company, Tin Shed", 1 photo, 1 data page, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. AK-9-F, "Green Butte Copper Company, Tram Terminus", 1 photo, 1 data page, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. AK-9-G, "Green Butte Copper Company, Warehouse", 3 photos, 1 data page, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. AK-9-H, "Green Butte Copper Company, Portal Shed", 6 photos, 2 color transparencies, 2 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. AK-9-I, "Green Butte Copper Company, Covered Stairway", 2 photos, 1 color transparency, 2 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. AK-9-J, "Green Butte Copper Company, Bunkhouse (Upper Camp)", 7 photos, 1 color transparency, 2 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- IUCN Category II

- Alaska Range

- ANILCA establishments

- Archaeological sites in Alaska

- Protected areas of Chugach Census Area, Alaska

- Protected areas of Copper River Census Area, Alaska

- Protected areas of Southeast Fairbanks Census Area, Alaska

- Protected areas of Yakutat City and Borough, Alaska

- Saint Elias Mountains

- World Heritage Sites in the United States

- Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve