Yoknapatawpha County

Yoknapatawpha County (/jɒknəpəˈtɔːfə/) is a fictional Mississippi county created by the American author William Faulkner, largely based on and inspired by Lafayette County, Mississippi, and its county seat of Oxford (which Faulkner renamed "Jefferson"). Faulkner often referred to Yoknapatawpha County as "my apocryphal county".[1][2][3]

Overview

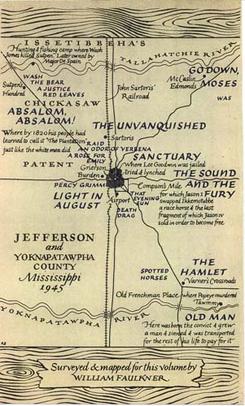

From Sartoris (1929) onwards, Faulkner set all but three of his novels in the county, as well as over 50 of his stories (the three later novels which were set elsewhere were Pylon, The Wild Palms, and A Fable).[4] Absalom, Absalom! includes a map of Yoknapatawpha County drawn by Faulkner.[5]

The word Yoknapatawpha is derived from two Chickasaw words—Yocona and petopha, meaning "split land." Faulkner said to a University of Virginia audience that the compound means "water flows slow through flat land." Yoknapatawpha was the original name for the actual Yocona River, a tributary of the Tallahatchie which runs through the southern part of Lafayette County. The first mention of the county, in Flags in the Dust (originally published as Sartoris), refers to it as "Yocona County."[6]

The area was originally Chickasaw land. European settlement started around the year 1800. Prior to the American Civil War, the county consisted of several large plantations. By family surname, they were: Grenier in the southeast, McCaslin in the northeast, Sutpen in the northwest, and Compson and Sartoris in the immediate vicinity of Jefferson. Later, the county became mostly small farms. By 1936, the population was 15,611, of which 6,298 were white and 9,313 were black.[7]

Richard Reed has presented a detailed chronological analysis of Yoknapatawpha County.[4] Charles S. Aiken has examined Faulkner's incorporation of real-life historical and geographical details into the overall presentation of the county.[8] Aiken has further discussed the parallels of Yoknapatawpha County with the real-life Lafayette County, and also the representation of the "Upland South" and the "Lowland South" in Yoknapatawpha.[9]

Faulkner's imaginary county has inspired at least one other Mississippi author to follow his lead: Jesmyn Ward, who is the only woman to win the National Book Award twice for fiction.[10] She drew upon Faulkner for Bois Sauvage, where she placed her three novels.[11]

See also

References

- ^ "Faulkner at Virginia: Transcript of audio recording wfaudio01_1". faulkner.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ McCrum, Robert (2014-10-06). "The 100 best novels: No 55 – As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (1930)". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ Meriwether, James B. (1970). "The Novel Faulkner Never Wrote: His Golden Book or Doomsday Book". American Literature. 42 (1): 93–96. doi:10.2307/2924385. ISSN 0002-9831.

- ^ a b Reed, Richard (Fall 1974). "The Role of Chronology in Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha Fiction". The Southern Literary Journal. 7 (1): 24–48. JSTOR 20077502.

- ^ Hamblin, Robert. "Faulkner's Map of Yoknapatawpha: The End of Absalom, Absalom!". Center for Faulkner Studies.

- ^ "Doctor Lucius Quintus Peabody, eighty-seven years old, ... had practiced medicine in Yocona county when a doctor's equipment consisted of a saw and a gallon of whisky and a satchel of calomel...." Flags in the Dust (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), pp. 94-95.

- ^ Faulkner, William (1936). "Yoknapatawpha, in Absalom ! Absalom !".

- ^ Aiken, Charles S. (January 1977). "Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County: Geographical Fact into Fiction". Geographical Review. 67 (1): 1–21. doi:10.2307/213600. JSTOR 213600.

- ^ Aiken, Charles S. (July 1979). "Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County: A Place in the American South". Geographical Review. 69 (3): 331–48. doi:10.2307/214889. JSTOR 214889.

- ^ Canfield, David. "Jesmyn Ward Wins National Book Award for 'Sing, Unburied, Sing'". The New York Times. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ Begley, Sarah. "Jesmyn Ward, Heir to Faulkner, Probes the Specter of Race In the South". Time. Retrieved December 13, 2018.