Zastrozzi

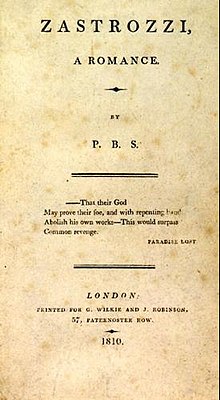

Title page from first edition | |

| Author | Percy Bysshe Shelley |

|---|---|

| Published | George Wilkie and John Robinson, 1810 |

| Pages | 119 (2002 edition) |

| ISBN | 9781843910299 |

| OCLC | 50614788 |

Zastrozzi: A Romance is a Gothic novel by Percy Bysshe Shelley first published in 1810 in London by George Wilkie and John Robinson anonymously, with only the initials of the author's name, as "by P.B.S.". The first of Shelley's two early Gothic novellas, the other being St. Irvyne, outlines his atheistic worldview through the villain Zastrozzi[1] and touches upon his earliest thoughts on irresponsible self-indulgence and violent revenge. An 1810 reviewer wrote that the main character "Zastrozzi is one of the most savage and improbable demons that ever issued from a diseased brain".

Shelley wrote Zastrozzi at the age of seventeen[2] while attending his last year at Eton College,[3] though it was not published until later in 1810 while he was attending University College, Oxford.[4] The novella was Shelley's first published prose work.

In 1986, the novel was released as part of the Oxford World's Classics series by Oxford University. Nicole Berry translated the novel in a French edition in 1999. A German translation by Manfred Pfister was published in 2007.

Major characters

- Pietro Zastrozzi, an outlaw who seeks revenge against Verezzi, his half-brother

- Verezzi, Il Conte, imprisoned by Zastrozzi

- Julia, La Marchesa de Strobazzo, intended wife of Verezzi

- Matilda, the Contessa di Laurentini, seduces Verezzi in plan devised by Zastrozzi

- Bernardo, servant to Zastrozzi

- Ugo, servant to Zastrozzi

- Ferdinand Zeilnitz, servant to Matilda

- Bianca, servant to Zastrozzi

- Claudine, old woman in Passau, shelters Verezzi

- The Monk

- The Inquisitor

- The Superior, a judge

Epigraph

The epigraph on the title page of the novel is from Paradise Lost (1667) by John Milton, Book II, 368–371:

—That their God

May prove their foe, and with repenting hand

Abolish his own works—This would surpass

Common revenge.

– Paradise Lost.

Plot

Pietro Zastrozzi, an outlaw, and his two servants, Bernardo and Ugo, disguised in masks, abduct Verezzi from the inn near Munich where he lives and take him to a cavern hideout. Verezzi is locked in a room with an iron door. Chains are placed around his waist and limbs and he is attached to the wall.

Verezzi is able to escape and to flee his abductors, running away to Passau in Lower Bavaria. Claudine, an elderly woman, allows Verezzi to stay at her cottage. Verezzi saves Matilda from jumping off of a bridge. She befriends him. Matilda seeks to persuade Verezzi to marry her. Verezzi, however, is in love with Julia. Matilda provides lodging for Verezzi at her castle or mansion estate near Venice. Her tireless efforts to seduce him are unsuccessful.

Zastrozzi concocts a plan to torture and to torment Verezzi. He spreads a false rumour that Julia has died, exclaiming to Matilda: "Would Julia of Strobazzo's heart was reeking on my dagger!" Verezzi is convinced that Julia is dead. Distraught and emotionally shattered, he then relents and offers to marry Matilda.

The truth is revealed that Julia is still alive. Verezzi is so distressed at his betrayal that he kills himself. Matilda kills Julia in retaliation. Zastrozzi and Matilda are arrested for murder. Matilda repents. Zastrozzi, however, remains defiant before an inquisition. He is tried, convicted, and sentenced to death.

Zastrozzi confesses that he sought revenge against Verezzi because Verezzi's father had deserted his mother, Olivia, who died young, destitute, and in poverty. Zastrozzi blamed his father for the death of his mother, who died before she was thirty. Zastrozzi sought revenge against not only his own father, whom he murdered, but also against "his progeny for ever", his son Verezzi. Verezzi and Zastrozzi had the same father. By murdering his own father, Zastrozzi only killed his corporeal body. By manipulating Verezzi into committing suicide, however, Zastrozzi confessed that his objective was to achieve the eternal damnation of Verezzi's soul based on the proscription of the Christian religion against suicide. Zastrozzi, an outspoken atheist, goes to his death on the rack rejecting and renouncing religion and morality "with a wild convulsive laugh of exulting revenge".[5]

Reception

The Gentleman's Magazine, regarded as the first literary magazine, published a favourable review of Zastrozzi in 1810: "A short, but well-told tale of horror, and, if we do not mistake, not from an ordinary pen. The story is so artfully conducted that the reader cannot easily anticipate the denouement." The Critical Review, a conservative journal with a "reactionary aesthetic agenda", on the other hand, called the main character Zastrozzi "one of the most savage and improbable demons that ever issued from a diseased brain." The reviewer dismissed the novella: "We know not when we have felt so much indignation as in the perusal of this execrable production. The author of it cannot be too severely reprobated. Not all his 'scintillated eyes,' his 'battling emotions,' his 'frigorific torpidity of despair'... ought to save him from infamy, and his volume from the flames."[6]

Zastrozzi was republished in 1839 in The Romancist and Novelist's Library: The Best Works of the Best Authors, Volume 1, No. 10, published in London by John Clements.[7]

The novel contains psychological and autobiographical components. Eustace Chesser, in Shelley and Zastrozzi (1965), analysed the novella as a complex psychological thriller: "When I first came across Zastrozzi I was immediately struck by its resemblance to the dream material with which every psychoanalyst is familiar. It was not a story told with the detachment of a professional writer for the entertainment of the public. Whatever the conscious intention of the young Shelley, he was in fact, writing for himself. He was opening the floodgates of the unconscious and allowing its fantasies to pour out unrestrainedly. He was betraying, unwittingly, the emotional problems that agitated his adolescent mind."[8]

Real experiences and actual people were projected on fictional events and characters. Subconscious conflicts are resolved in the writing process. Patrick Bridgwater, in Kafka, Gothic and Fairytale (2003), argued that the novella anticipated Franz Kafka's work in the twentieth century.[9]

Stylistically, the novella reveals several flaws. The most striking flaw is missing chapters, although some critics and editors[6] have argued that Shelley intended this omission as a prank. At about one hundred pages, Zastrozzi is shorter than novel-length, which prevents a more thorough and complete development of the characters. In the middle sections of the novella, moreover, there is not enough variation in the setting.[6] There is a primary focus on Verezzi and Matilda at the exclusion of the other characters and at the expense of the plot development. Shelley also experiments with word selection and structure which tends to slow down the flow of the story.[6]

Adaptations

In 1977, Canadian playwright George F. Walker wrote a successful play adaptation called "Zastrozzi, The Master of Discipline" based on the Shelley novella. The play was based on a plot summary of Shelley's work, but in and of itself was something "rather different from the novel," in the author's words. The play has repeatedly been revived and was part of the 2009 season of the Stratford Shakespeare Festival.[10] Walker's play retains all the major characters of the Shelley novella, the core plot, and the moral and ethical issues relating to revenge and retribution and atheism. The play has been in continuous production worldwide since it was published in 1977.

In 1986, Channel Four Films in Britain produced a four-part television mini-series of the Shelley novella as Zastrozzi, A Romance, adapted and directed by David G. Hopkins and produced by Lindsey C. Vickers and David Lascelles, shown on Channel Four. The series was also shown on American television on PBS in a version by WNET on the "Channel Crossings" program.[11] Mark McGann played Verezzi, Tilda Swinton played Julia, Hilary Trott played Matilda, Max Wall was the Priest, while Zastrozzi was played by newcomer Geff Francis. The production consisted of four 52-minute episodes. In 1990, Jeremy Isaacs named the dramatisation of Zastrozzi as one of the 10 programmes of which he was most proud during his tenure as Channel 4's chief executive.[12]

The entire four-part miniseries Zastrozzi, A Romance was released on DVD on two discs on 8 October 2018 in the UK.

Similarities to Frankenstein

There are similarities between Zastrozzi and Frankenstein in terms of imagery, style, themes, plot structure and character development. Phillip Wade noted how the allusions to John Milton's Paradise Lost are present in both novels:[13]

"Shelley's earlier characterization of Zastrozzi with his 'lofty stature' and 'dignified mein and dauntless composure' clearly owed much to Milton's Satan, as did that of Wolfstein in St. Irvyne, described as having a 'towering and majestic form' and 'expressive and regular features ... pregnant with a look as if woe had beat to earth a mind whose native and unconfined energies had aspired to heaven.' In this second romance Shelley had also pictured a character 'whose proportions, gigantic and deformed, were seemingly blackened by the inerasable traces of the thunderbolts of God.' This kind of description, so patently imitative of Milton's characterization of Satan, is as evident in Frankenstein as it is in Shelley's juvenile romances."

He described a scene in Zastrozzi that is repeated in Frankenstein:

"To give an example: in Zastrozzi there is a scene played in a conventional Alpine setting. A lightning storm, properly terrifying, rattles from crag to crag. And there Matilda: 'Contemplated the tempest which raged around her. The battling elements paused, an uninterrupted silence, deep, dreadful as the silence of the tomb, succeeded. Matilda heard a noise -- footsteps were distinguishable, and looking up, a flash of lightning disclosed to her view the towering form of Zastrozzi. His gigantic figure was again involved in pitchy darkness, as the momentary lightning receded. A peal of crashing thunder again madly rattled over the zenith, and a scintillating flash announced Zastrozzi's approach, as he stood before Matilda.'

He found that the "identical" scene is replicated in Frankenstein:[14]

"The identical scene occurs in Frankenstein, with Victor Frankenstein finding himself in the Alps during an electrical storm: 'I watched the storm, so beautiful yet terrific ... This noble war in the sky elevated my spirits; I clasped my hands, and exclaimed aloud, "William, dear angel! this is thy funeral, this is thy dirge!' As I said these words, I perceived in the gloom a figure ... A flash of lightning illuminated the object, and discovered its shape plainly to me, its gigantic stature ... instantly informed me it was the wretch, the filthy demon, to whom I had given life.'"

He concluded that both books show Shelley's use of Miltonic themes:

"Granted, storm scenes are not unusual in Romantic literature; one need only recall Byron's Childe Harold. But the Miltonic image of a titanic Satan silhouetted by fires in the pitchy blackness of Hell bears the unmistakable mark of Shelley's influence."

Stephen C. Behrendt noted that the plan for getting revenge upon God in Zastrozzi, as referenced in the epigraph, "anticipates the guerilla warfare that the Creature will wage on Victor Frankenstein":

"Speaking to the assembly of fallen angels in Hell, Beelzebub is proposing a means of achieving revenge against God. His plan calls for attacking God by sabotaging the creatures most dear to him, Adam and Eve, so that an angry and regretful God will condemn them to destruction, a scheme that anticipates the guerilla warfare that the Creature will wage on Victor Frankenstein in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein."[15]

Jonathan Glance compared the dream in Frankenstein with that in Zastrozzi: "The final and closest analogue to Victor Frankenstein's dream occurs in Percy Shelley's Zastrozzi (1810)." Matilda's reaction is described: "At one point she imagined that Verezzi, consenting to their union, presented her his hand: that at her touch the flesh crumbled from it, and, a shrieking spectre, he fled from her view".[16]

Shelley's later prose fiction

In 1811, Shelley wrote a follow-up novella to Zastrozzi called St. Irvyne; or, The Rosicrucian, A Romance, about an alchemist who sought to impart the secret of immortality, published by John Joseph Stockdale, at 41 Pall Mall, in London, which relied more on the supernatural than did Zastrozzi, which was imbued with Romantic realism.

The principal fictional prose writings of Shelley are Zastrozzi, St. Irvyne, The Assassins, A Fragment of a Romance (1814), an unfinished novella about a morality-driven sect of zealots determined to kill the tyrants and oppressive dictators in the world, The Coliseum[17] (1817), Una Favola (A Fable), written in Italian in 1819, and The Elysian Fields: A Lucianic Fragment (1818), which presents fictional fantasy with political commentary.[18] The chapbooks Wolfstein; or, The Mysterious Bandit (1822) and Wolfstein, the Murderer; or, The Secrets of a Robber's Cave (1830) were condensed versions of St. Irvyne. A True Story was attributed to him from the 1820 Indicator by Leigh Hunt, which is similar to the poem The Sunset (1816). Shelley also wrote the preface and contributed at least 4,000–5,000 words to the Gothic novel Frankenstein (1818) by his wife Mary Shelley.[19] There is a continuing debate about how much he wrote of the novel. In 2008, he was given co-writer or collaborator status in publications of the novel from Random House, Oxford University Press, and University of Chicago Press.[20][21][22][23]

References

- ^ Percy Bysshe Shelley, Academy of American Poets

- ^ Early Shelley: Vulgarisms, Politics, and Fractals, Romantic Circles

- ^ Sandy, Mark (7 July 2001). "Percy Bysshe Shelley". The Literary Encyclopedia. The Literary Dictionary Company. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- ^ Percy Bysshe Shelley Biography, Poem of Quotes.com

- ^ Zastrozzi by Percy Bysshe Shelley. The University of Adelaide, Australia.

- ^ a b c d Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Zastrozzi: A Romance; St. Irvyne, or, The Rosicrucian: A Romance. Edited, with an Introduction and Notes by Stepehen C. Behrendt. Peterborough, Ontario, Canada: Broadview Press, 2002

- ^ The Romancist, and Novelist's Library: The Best Works of the Best Authors, Volume 1, No. 10, 1839, page 145.

- ^ Chesser, Eustace. Shelley and Zastrozzi: Self-Revelation of a Neurotic. London: Gregg/Archive, 1965. Eustace Chesser: "The story itself had the incoherence of a dream because that is just what it was – a day dream in which our conscious conflicts were worked out in disguise."

- ^ Bridgwater, Patrick. Kafka, Gothic and Fairytale. NY: Rodopi, 2003. Patrick Bridgwater: "Zastrozzi is more interesting than it is generally allowed: ... it comes into its own when considered side by side with Kafka's work."

- ^ Stratford Festival. Past Productions. 2009. Zastrozzi.

- ^ O'Connor, John J. "TV View: 'Channel Crossings' Brings Sense of Surprise", 2 November 1986, New York Times. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Furse, John. "David Hopkins: Filmmaker with a passion for all things independent," The Guardian, 15 June 2004. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Wade, Phillip. "Shelley and the Miltonic Element in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein." Milton and the Romantics, 2 (December 1976), 23-25. A scene from Zastrozzi is re-invoked in Frankenstein.

- ^ Mary Shelley's Reading. Romantic Circles. She read Zastrozzi in 1814.

- ^ Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Zastrozzi and St. Irvyne. Edited by Stephen C. Behrendt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986, p. 59.

- ^ Glance, Jonathan. (1996). "'Beyond the Usual Bounds of Reverie'? Another Look at the Dreams in Frankenstein." Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, 7.4: 30–47.

- ^ Binfield, Kevin. "May they be divided never: Ethics, History, and the Rhetorical Imagination in Shelley's The Coliseum," Keats Shelley Journal, 46, 1997, pages 125-147.

- ^ Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Shelley's Prose: Or, The Trumpet of a Prophecy. Edited, with an Introduction and Notes by David Lee Clark. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1954.

- ^ Robinson, Charles E. "Percy Bysshe Shelley's Text(s) in Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's Frankenstein", in The Neglected Shelley edited by Alan M. Weinberg and Timothy Webb.London and New York: Routledge, 2015, pp. 117–136.

- ^ Rosner, Victoria. "Co-Creating a Monster." The Huffington Post, 29 September 2009. "Random House recently published a new edition of the novel Frankenstein with a surprising change: Mary Shelley is no longer identified as the novel's sole author. Instead, the cover reads 'Mary Shelley (with Percy Shelley).'"

- ^ Shelley, Mary, with Percy Shelley. The Original Frankenstein. Edited and with an Introduction by Charles E. Robinson. Oxford: The Bodleian Library, 2008. ISBN 1-85124-396-8 ISBN 978-1851243969

- ^ Murray, E.B. "Shelley's Contribution to Mary's Frankenstein," Keats-Shelley Memorial Bulletin, 29 (1978), 50-68.

- ^ Rieger, James, edited, with variant readings, an Introduction, and, Notes by. Frankenstein, Or the Modern Prometheus: The 1818 Text. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1982. Rieger concluded that Percy Bysshe Shelley's contributions are significant enough to regard him as a "minor collaborator": "His assistance at every point in the book's manufacture was so extensive that one hardly knows whether to regard him as editor or minor collaborator. ... Percy Bysshe Shelley worked on Frankenstein at every stage, from the earliest drafts through the printer's proofs, with Mary's final 'carte blanche to make what alterations you please.' ... We know that he was more than an editor. Should we grant him the status of minor collaborator?"

Sources

- Cameron, Kenneth Neill (1950). The Young Shelley: Genesis of a Radical. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-374-91255-6.

- Lauritsen, John. The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein. Dorchester, MA: Pagan Press, 2007.

- de Hart, Scott D. Shelly Unbound: Discovering Frankenstein's True Creator. Port Townsend, WA, U.S.: Feral House, 2013. Also as Shelley Unbound: Uncovering Frankenstein's True Creator.

- Chesser, Eustace. Shelley and Zastrozzi: Self-Revelation of a Neurotic. London: Gregg/Archive, 1965. Eustace Chesser: "The story itself had the incoherence of a dream because that is just what it was – a day dream in which our conscious conflicts were worked out in disguise."

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Zastrozzi. With a foreword by Germaine Greer. London: Hesperus Press, 2002. Germaine Greer: "The whole novel treats a love that still dare not speak its name, the love of a juvenile for adult women."

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Zastrozzi: A Romance; St. Irvyne, or, The Rosicrucian: A Romance. Edited, with an Introduction and Notes by Stepehen C. Behrendt. Peterborough, Ont., Canada: Broadview Press, 2002.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Zastrozzi and St. Irvyne. (The World's Classics). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. The Prose Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Edited by Harry Buxton Forman, 8 volumes. London: Reeves and Turner, 1880.

- Rajan, Tilottama. "Promethean Narrative: Overdetermined Form in Shelley's Gothic Fiction." Shelley: Poet and Legislator of the World, ed. Betty T. Bennett and Stuart Curran (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 240–52, 308–9.

- Zimansky, Curt R. (1981). "Zastrozzi and The Bravo of Venice: Another Shelley Borrowing." Keats-Shelley Journal, 30, pp. 15–17.

- Frosch, Thomas R. Shelley and the Romantic Imagination: A Psychological Study. University of Delaware Press, 2007.

- Bridgwater, Patrick. Kafka, Gothic and Fairytale. Rodopi, 2003. Patrick Bridgwater: "Zastrozzi is more interesting than it is generally allowed: ... it comes into its own when considered side by side with Kafka's work."

- Hughes, A.M.D. (1912). Shelley's Zastrozzi and St. Irvyne. Modern Language Review.

- Hughes, A.M.D. The Nascent Mind of Shelley. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1947.

- Seed, David. (1984). "Mystery and Monodrama in Shelley's Zastrozzi." Dutch Quarterly Review, 14.i, pp. 1–17.

- Day, Aidan. Romanticism. NY: Routledge, 1996.

- Shepherd, Richard Herne, ed. The Prose Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley: From the Original Editions. London: Chatto and Windus, 1888.

- Crook, Nora and Derek Guiton. Shelley's Venomed Melody. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Bonca, Teddi Chichester. Shelley's Mirrors of Love: Narcissism, Sacrifice, and Sorority. NY: SUNY Press, 1999.

- Clark, Timothy. (1993). "Shelley's 'The Coliseum' and the Sublime." Durham University Journal, 225–235.

- Duffy, Cian. (2003). "Revolution or Reaction? Shelley's 'Assassins' and the Politics of Necessity." Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 52, pp. 77–93.

- Duffy, Cian. Shelley and the Revolutionary Sublime. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Clark, Timothy. Embodying Revolution: The Figure of the Poet in Shelley. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Kiley, Brendan. "Zastrozzi: Percy Shelley’s Murder-Revenge Camp." The Stranger, Seattle, WA, 28 October 2009.

- Barker, Jeremy M. "The Balagan's Zastrozzi Delivers Sex & Violence Without a Pesky Purpose." The Sun Break, 12 October 2009.

- "Zastrozzi and the Price of Passion." Viva Victoriana, 9 September 2009.

- Glance, Jonathan. (1996). "'Beyond the Usual Bounds of Reverie'? Another Look at the Dreams in Frankenstein." Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, 7.4: 30–47. "Mary Shelley's journal indicates she read ... not long before composing Frankenstein ... Zastrozzi in 1814." There are "analogous" dream images and themes in both works: "The final and closest analogue to Victor Frankenstein's dream occurs in Percy Shelley's Zastrozzi (1810)."

- Simpkins, Scott. "Encoding Masculinity in the Gothic Novel: Shelley's Zastrozzi." California Semiotic Circle Conference, January 1997, Berkeley, CA.

- Neilson, Dylan. "Zastrozzi: Master of Stage". The Gauntlet, 27 January 2005.

- Halliburton, David G. (Winter, 1967). "Shelley's 'Gothic' Novels." Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 16, pp. 39–49.

- "Shelley's Novels." The New York Times, 28 November 1886.

- Sigler, David. "The Act of Objectification in P.B. Shelley‟s Zastrozzi." International Conference on Romanticism (ICR), Towson University, Baltimore, MD, October 2007.

- Young, A. B. (1906). "Shelley and M.G. Lewis." Modern Language Review, 1: pp. 322–324.

- Rich, Frank. "Stage: Serban Directs 'Zastrozzi' at the Public." The New York Times, 18 January 1962.

- Simpkins, Scott. "Tricksterism in the Gothic Novel." The American Journal of Semiotics, 1 January 1997.

- Cottom, Daniel. "Gothic Pathologies: The Text, The Body and The Law." Studies in Romanticism, 22 December 2000.

- Hagopian, John V. (1955). "A Psychological Approach to Shelley's Poetry." American Imago, 12: 25–45.

- Livingston, Luther S. "First Books of Some English Authors: Percy Bysshe Shelley." The Bookman, XII, 4, December 1900.

- Lovecraft, H. P. "Supernatural Horror in Literature." The Recluse, No. 1 (1927), 23–59.

- Wade, Phillip. "Shelley and the Miltonic Element in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein." Milton and the Romantics, 2 (December 1976), 23–25. A scene from Zastrozzi is re-invoked in Frankenstein.

External links

Zastrozzi, A Romance public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Zastrozzi, A Romance public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Online edition of Zastrozzi on the Project Gutenberg website.

- The Prose Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Volume 1

- "A British Adaptation of Shelley's Zastrozzi", New York Times, 16 October 1986

- Zastrozzi, A Romance (1986) – UK television mini-series on IMDB.

- 1810 British novels

- British novellas

- British Gothic novels

- British horror novels

- British romance novels

- Books with atheism-related themes

- British mystery novels

- British crime novels

- British psychological novels

- Works by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Works published anonymously

- British novels adapted into television shows