Adler (locomotive)

| Adler | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Replica of Adler (1935, rebuilt 2007) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two replicas in existence, one of them serviceable | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Adler (German for "Eagle") was the first locomotive that was successfully used commercially for the rail transport of passengers and goods in Germany. The railway vehicle was designed and built in 1835 by the British railway pioneers George and Robert Stephenson in the English city of Newcastle. It was delivered to the Bavarian Ludwig Railway (Bayerische Ludwigsbahn) for service between Nuremberg and Fürth. It ran officially for the first time there on 7 December 1835. The Adler was a steam locomotive of the Patentee type with a wheel arrangement of 2-2-2 (Whyte notation) or 1A1 (UIC classification). The Adler was equipped with a tender of type 2 T 2. It had a sister locomotive, the Pfeil.

History

[edit]Earlier locomotives in Germany

[edit]The Adler is often cited as the very first locomotive used by a railway company on German soil, but as early as 1816 a serviceable steam locomotive was designed by the Royal Prussian Steelworks (Königlich Preußische Eisengießerei) in Berlin. During a trial run this so-called Krigar locomotive hauled one railway wagon with a payload of 8,000 German pounds (about 4.48 tonnes or 4.41 long tons or 4.94 short tons). But this vehicle was never used commercially.[1][2] Nevertheless, the Adler was undoubtedly the first successfully operated locomotive in regular use in Germany.

Origin

[edit]

During the construction of the Bavarian Ludwig Railway, founded by Georg Zacharias Platner, the search for a suitable locomotive started in England.

The first letter of enquiry was sent via the London company, Suse und Libeth, to Robert Stephenson & Co. and Braithwaite & Ericsson. The locomotive was to be able to pull a weight of ten tonnes (9.8 long tons; 11 short tons) and cover the distance between Nuremberg and Fürth in a time of eight to ten minutes. Carriages were heated with charcoal. Stephenson replied that a locomotive of the same build class as those on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, with four wheels and a weight of between seven point five and eight tonnes (7.4 and 7.9 long tons; 8.3 and 8.8 short tons), could be supplied. A lighter engine would not have the necessary power of adhesion and would be more expensive than a heavier engine. In any case, on 16 June 1833, Johannes Scharrer asked for a quote for two locomotives with a weight of 6.5 tonnes (6.4 long tons; 7.2 short tons) and the necessary package of accessories. Stephenson quoted a cost of about £1,800. The German company, Holmes and Rolandson from Unterkochen near Aalen, offered a steam locomotive with a power of between two and six horsepower (1.5 and 4.5 kW) at a price of 4,500 Gulden. Negotiations with Holmes and Rolandson stalled, and this avenue of enquiry was dropped.

A further bid came from Josef Reaullaux located in Eschweiler, near Aachen. At the end of April, Platner and Mainberger from Nuremberg were in Neuwied near Cologne. There they wanted to award a contract for the railway track. On 28 April they travelled to Cologne to meet with a friend of Platner called Consul Bartls. Bartls told them about the Belgian engineering works of Cockerill in Liège.

As a result, Platner and Mainberger travelled to Liège. There they discovered that Cockerill had not yet built a locomotive, though they did find Stephenson was in Brussels at that time. They reached Brussels on 1 May and stayed in a guesthouse in Flanders, where Stephenson and several of his engineers were staying. Stephenson wanted to be present at the opening of the railway line from Brussels to Mechelen which was scheduled for 5 May. On 3 May, both parties signed a letter of intent. Stephenson wanted to deliver a locomotive of the Patentee type with six wheels and a weight of about 6 tonnes (5.9 long tons; 6.6 short tons) for a price of between £750 and £800. On 15 May 1835 the new locomotive was ordered from Stephenson's locomotive works in Newcastle upon Tyne to those specifications. Furthermore, a tender for a bogie passenger coach and a goods wagon were ordered. Later it turned out that the locomotive would cost about £900 instead of the sum quoted in Brussels. Stephenson originally promised in Brussels that the locomotive would be delivered by the end of July to Rotterdam[3]

Different units of measurement were used in Nuremberg and England; the English foot and the Bavarian foot were different. The track gauge was predefined to be the same as that of the Stockton and Darlington Railway which was 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in). Stephenson persisted with this gauge which meant the existing track had to be relaid, because its track gauge was too narrow by 5⁄8 inch (16 mm). The delivery of the locomotive to Nuremberg, together with all its spares comprising over 100 individual components in 19 boxes with a total weight of 177 long hundredweight (19,800 lb; 9,000 kg), came to a cost of £1,140/19/3.[a] The boxes were shipped late, on 3 September 1835, on the ship Zoar from London to Rotterdam. The freight rate from Rotterdam to Cologne was 700 francs, from Cologne to Offenbach am Main 507 South German gulden and 9 kreuzer and from Offenbach to Nuremberg 653 gulden and 11 kreuzer. The board of directors of the Bavarian Ludwig Railway wanted the purchase to be exempted from import duty. The locomotive was declared as an item of a formerly unknown product which was to be used by factories in the Bavarian interior. After several difficulties the Ministry of Finance approved the tax-free import with Johann Wilhelm Spaeth as the recipient of the consignment.[4]

The transport boxes containing the locomotive were shipped by the barge van Hees (owned by its captain, van Hees) and pulled upriver by the steamboat Hercules on the Rhine until it reached Cologne.[5] As the waterline in the Rhine was low, Captain van Hees had to use horses to pull the barge instead of the steamboat, as originally planned.[4] On 7 October, the train of barges reached Cologne; the remaining distance to Nuremberg had to be covered by road because the Main was too shallow to be navigable by barge. The transport on land was disrupted by a strike of the freight forwarders in Offenbach am Main, and a different freight forwarder had to be ordered. On 26 October 1835 the transport reached Nuremberg. The steam engine was assembled in the workshops of the Johann Wilhelm Spaeth engineering works, with the assembly being observed by Stephenson's engineer William Wilson, who had travelled with the locomotive to Nuremberg. They used the help of the technical teacher Bauer and local carpenters.

On 10 November 1835, the board of directors of the Bavarian Ludwig Railway expressed their hope that the locomotive would be serviceable soon.[4] The locomotive was a symbol for power, daringness and rapidity.[6]

Both bogies delivered by Robert Stephenson & Co. turned out as too heavy for use at Nuremberg. The German constructor Paul Camille von Denis had planned that the railway wagons should be pulled either from the steam locomotive, or from horses, making a lighter construction necessary. Several companies built the wagons:

- the bogies were produced by Späth, Gemeiner und Manhard;

- the wooden coachwork were delivered by the wheelwright Stahl from Nuremberg.

As these companies were used to capacity with different orders three bogies and 16 wheels were produced by the company Stein in Lohr near Aschaffenburg. Denis threatened these companies that he would place future orders in England if they would not work faster. At the end of August 1835 the first wagon was completed. In the second half of October that year, further wagons were nearing completion, with nine wagons produced before the opening of the Bavarian Ludwig Railway. The wagons consisted of two wagons for third class passengers, four for second class and three for first class. On 21 October 1835, the first test run with one horse-pulled wagon took place. Denis had constructed a brake for the wagons which was tested at this opportunity. The wagon could be stopped in each situation without any effort by the horse.

On 16 November, the first test run of the steam locomotive from Nuremberg to Fürth and back again was accomplished. Due to the cold weather that day, the speed was reduced. Three days later, five fully occupied wagons were transported on the track in 12 to 13 minutes. On the way back the brakes and also boarding and disembarking of the passengers were tested. During the following tests it was discovered that, if wood was burned in the locomotive, the sparks which came out of its chimney singed the clothing of the passengers. The passengers' participation in the test run cost 36 kreuzer each, and the revenues from this were donated to the welfare of the poor.[4]

Construction and bodywork

[edit]Locomotive

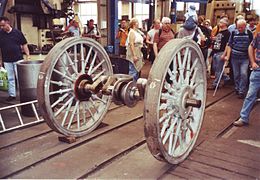

[edit]The Adler was built on a wooden framework which was covered with sheet metal. Both wet steam driven cylinders were placed horizontally inside the frame and drove the driving wheelset which was placed in the middle of the three axles. The driving wheels had no wheel flange, so the locomotive could be operated on small radius curves. The forged spokes were rivetted to the rim. The original wheels were made of cast iron and were encircled with a forged tyre made of wrought iron. The original wheels made of brittle cast iron were replaced later through wheels made of wrought iron. The hollow spokes had a core made of wood to make them more flexible to cushion unevenness of the track. All wheels of the locomotive were unbraked. A mechanical railway brake braked both wheels of the tender on the right side where the fireman was located. There was a fixed connection between the locomotive and the tender. The buffers were made of wood. The horseshoe-shaped water box surrounded the coal stored in the tender. At first coke was burned in the firebox, later bituminous coal was used.[7][8]

Railway coaches

[edit]The passenger wagons had the same bodies that were used for horse-drawn carriages. They were mounted on a bogie made of iron. The shape of coupé-carriages with two axles and three separated compartments in line was the archetype for the first German railway wagons. Specific bogies for passenger coaches were first developed in 1842 by the Great Western Railway. All wagons were painted in yellow which was the colour of stagecoaches at that time. The third class wagons originally had no roof, three compartments with eight to ten seats and the entrances had no doors. The second class wagons had originally a roof made of canvas, had doors, unglazed windows and curtains originally made of silk later made of leather. All wagons were of the same width but from the cheapest to the most expensive class the number of seats in one line were reduced by one. The first class wagons were lined with a precious blue foulard, had windows made of glass, the door handles gilded and all metal fittings were made of brass. The second class wagon No 8 which still exists was rebuilt between 1838 and 1846, it has a length of 5,740 mm (18 ft 10 in), a weight of about 5 t (4.9 long tons; 5.5 short tons) and has 24 seats.

Operation and retirement

[edit]

On 7 December 1835 the Adler, driven by William Wilson, ran for the first time on the 6.05 kilometres long track of the Ludwigsbahn[9] in nine minutes. 200 guests of honour were on the train and 26-year-old Northumbrian William Wilson was in the cab. In time intervals of two hours two more test runs were made. The locomotive was in use with up to nine wagons with 192 passengers as a maximum. In normal use it drove at a maximum speed of 28 km/h because the locomotive should be preserved. The normal run time was about 14 minutes. Demonstration trial could be done at a maximum speed of 65 km/h. In most cases horses were used as working animals instead of the steam locomotive. Because the coal was first very expensive most services were done as a horsecar. Goods were transported additionally to the passengers beginning from the year 1839. One of the first goods which were transported were beer barrels and cattle. In 1845 there was a considerable transport of goods.

After running successfully for twenty-two years the Adler was now the weakest locomotive on the European continent. Moreover, the coal of newer steam engines was much more efficient until then. The locomotive was used in Nuremberg as a stationary steam engine. It was scrapped in 1855, and in 1858 the railway company sold the locomotive with the tender but minus its wheels and further accessories to the iron dealer Mr. Director Riedinger located in Augsburg.[10] A probably unique photograph of the Adler taken around 1851, and probably the only one in existence, is in the Nuremberg city archives (Stadtarchiv Nürnberg).[11] However, neither the age of the photograph is documented definitely nor is known if the picture shows the original locomotive or only a model. The second class passenger wagon No 8, built in 1835 and rebuilt between 1838 and 1846, was preserved because Ludwig I of Bavaria is supposed to have travelled in it.

Replicas

[edit]Serviceable replica of 1935

[edit]

In 1925, the establishment of the Nuremberg Transport Museum was planned. It was decided that the Adler, which had been scrapped in 1855, should be reconstructed. The exact plans from that era were lost. Only one engraving from the time of the historical Adler provided information. In 1929 these plans were halted by the Great Depression.

To celebrate the centenary of the railways in Germany in 1935, a replica of the Adler was built beginning from 1933 by the Deutsche Reichsbahn in the Kaiserslautern repair shop (Ausbesserungswerk), which was largely true to the original. The original idea of the President of the Reichsbahn Julius Dorpmüller and the members of his staff was to use the Adler-replica as an instrument of propaganda for the "new era" in the city of the Reichsparteitag Nuremberg. They planned to contrast the Adler with modern gigantic steam locomotives like the high-speed DRG Class 05. For the realisation of the replica they used the results of the planning in 1925. Besides of different technical data the replica differed from the original with thicker boiler casing and additional cross bracings and spokes wheels made of steel.[12] The replica attained an average speed of 33.7 km/h in tests on an 81 kilometre stretch of line. The route had gradients of between 1:110 and 1:140. From 14 July until 13 October 1935, visitors could travel with the reconstructed Adler-train on a track length of two kilometres on the area of the centenary exhibition in Nuremberg. On the driving cab were also the President of the Deutsche Reichsbahn Julius Dorpmüller and the Gauleiter of Franconia Julius Streicher. The Adler-replica was in use after that in 1936 at the Cannstatter Wasen in Stuttgart and during the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. During the 100-years-jubilee of the first Prussian railway in 1938 the Adler-train was in service between Berlin and Potsdam. After this event the Adler-train was sent to the Nuremberg Transport Museum.

In 1950, the Adler-train was displayed by the Deutsche Bundesbahn on a street transport vehicle for rolling stock during a parade of the 900-years-jubilee of Nuremberg.[13]

For the 125th anniversary of the railway in Germany the Adler-train was in service on the track of the tram between Nuremberg (Plärrer place) and Fürth Hauptbahnhof. The inner sides of the wheels were needed to turned of for operating on the tram track.[14]

In 1984, it was rebuilt for the 150th anniversary by the Deutsche Bundesbahn in the Offenburg repair shop. The inner sides of the wheels which were turned of in 1960 for driving on a tram track had to welded again. The steam boiler was checked under notice of current safety regulations. The Adler was displayed on the great jubilee exhibition in Nuremberg and took part of numerous events in west Germany like for example in Hamburg, Konstanz and Munich. On 22 May 1984 it was used for public tours between Nürnberg Hauptbahnhof and Nuremberg East.[15]

The locomotive was out of service from 1985 until 1999. For the planned services in 1999, it had to be refurbished during several months. On 16 September 1999, the Federal Railway Authority gave the approval of operation.[16] For the 100th anniversary of the Bavarian Railway Museum and the successor Nuremberg Transport Museum in 1999 the Adler-train was in service at three Sundays in October and took part in the great parade of rolling stock at the Nuremberg classification yard. In the following years the Adler-train was used for several classic railway tours in Germany.[17] It stood in the Nuremberg Transport Museum until 2005 when it was damaged by fire.[18]

The still-working Adler replica was one of many engines that were badly damaged when a fire broke in the museum's roundhouse at the Nuremberg West locomotive depot on 17 October 2005. Nevertheless, the management of the Deutsche Bahn decided to restore it. The wreck was lifted from the ruins of the roundhouse on 7 November by a mobile crane in a four-hour operation by a recovery gang from the Preßnitz Valley Railway and taken by special low-loader to the Meiningen Steam Locomotive Works. It was discovered that the boiler at least, thanks to its being full of water, was relatively undamaged, although its entire wooden cladding had been burnt and many plates had melted, and it could therefore be used for the reconstruction in 2007.

Reconstruction in a serviceable state in 2007

[edit]

The reconstruction started on April 25, 2007, and was finished by October 8th 2007.[19][20] The metal-sheathed wooden frame was however so badly damaged, that it had to be completely built from scratch. A third-class wagon that had been stored at a different location and so had survived the fire, served as a template for the new coach-like wagons that were built by a Meiningen carpenter's shop. The cost ran to about a million euros, of which 200,000 euros was donated by the public.[21] The director of the DB Museum Nuremberg assuaged fears before the reconstruction began that the rebuilding work would not be able to replicate the details of the locomotive damaged by the fire and explained: "No compromises will be made!" It was even more accurately built by using historical drawings, so for example the reconstruction of the chimney damaged in the fire was not based on the 1935 replica, but on the original design. The biggest problem was the one-piece driving axle. This could not be made in the Meiningen works, so at short notice the company Grödlitzer Kurbelwelle Wildau GmbH was found which could carry out the work. For the frame of the locomotive between eight and twelve years seasoned wood from fraxinus-trees was used. This was flexible enough for vibrations by the power transmission during a run. The base frame of the tender was built from hard wood taken from oak-trees.[22]

On 23 November 2007 the restored Adler returned to display at the museum together with an old third class wagon from 1935 and two new ones from 2007 in a locomotive shed near the Nuremberg Transport Museum. In the museum the non-serviceable replica from 1950 is displayed and also the original second class 1835 built and 1838 and 1846 rebuilt passenger wagon No 8 of the Bavarian Ludwig Railway which has not been put on track again because of conservation reasons. On 26 April 2008 the replica was in use between Nuremberg and Fürth accompanied by German members of parliament of various parties, a member of the DB management board and the Bavarian minister-president, Beckstein. In May special runs in Nuremberg, Koblenz and Halle (Saale) were following during the summer. In April 2010 during the 175th anniversary of the railway in Germany the Adler was in use of the area of the DB Museum in Koblenz-Lützel. In May and June runs with visitors between Nürnberg Hauptbahnhof and Fürth Hauptbahnhof were made.

-

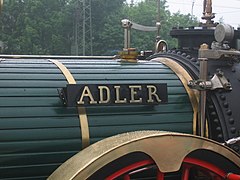

Name plate of the Adler replica

-

Driving axle, September 2006

-

Boiler and chimney, September 2006

-

View from front right, September 2007

-

Close-up from rear right, September 2007

-

burned locomotive frame made from wood of the 1935 replica, September 2007

-

Replica (1935) of a third class wagon which was a master for building new wagons, September 2007

-

New tender bodywork, September 2007

Non-serviceable replica of the 1950s

[edit]Another replica that, unlike the 1935 version, is not operational, was appointed by the advertising office of the Deutsche Bundesbahn and built during the 1950s at the Ausbesserungswerk in Munich-Freimann. This replica was used for public relations purpose on exhibitions and fairs. It is to be found as a display model in the Nuremberg Transport Museum.[23]

Further replicas and pictures

[edit]Since 1964 a 1:2 scale, motorised replica, the "Mini-Adler", had run at Nuremberg Zoo. It started in the vicinity of the entrance and shuttled to the children's zoo. In the course of the dolphin lagoon project this line had to be closed, but an extension or move of the route is planned.

The Görlitzer Oldtimer Parkeisenbahn uses a replica on a narrow gauge railway with a track gauge of 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in). This replica is in fact a diesel locomotive.

As part of the town's millennium celebrations "1000 years in Fürth" a bus was decorated with the Adler, and advertised an exhibition, at which donations for the reconstruction were collected.

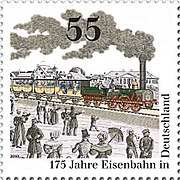

In the stamp-volumes of the Reichspost from 1935, the Deutsche Bundespost from 1960, the Deutsche Post of the GDR from 1960 and the Deutsche Bundespost from 1985 the Adler was appreciated to the jubilees of "100", "125", and "150" years of German railways. At the 175th anniversary in 2010 a 55 eurocent commemorative stamp with a picture of the Adler was issued by the Deutsche Post AG. Also a 10 Euro commemorative coin of the mint in Munich (D) with the following inscription on the edge Auf Vereinten Gleisen 1835 - 2010 (= On united tracks 1835 - 2010).

- Pictures of the Adler on German stamps and votive medals

-

Deutsche Bundespost, 1960

-

Deutsche Post AG, 2010

See also

[edit]Literature

[edit]- DB Museum Nürnberg, Jürgen Franzke (ed.): Der Adler - Deutschlands berühmteste Lokomotive (Objektgeschichten aus dem DB Museum, Band 2). Tümmel Verlag, Nuremberg, 2011, ISBN 978-3-940594-23-5.

- Garratt, Colin und Max Wade-Matthews: Dampf. Eurobooks Cyprus Limited, Limassol 2000. ISBN 3-89815-076-3.

- Hehl, Markus: Der "Adler" - Deutschlands erste Dampflokomotive. Verlagsgruppe Weltbild, Augsburg 2008.

- Heigl, Peter: Adler - Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg, June 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1.

- Herring, Peter: Die Geschichte der Eisenbahn. Coventgarden bei Doring Kindersley, Munich, 2001, ISBN 3-8310-9001-7.

- Hollingsworth, Brian und Arthur Cook: Das Handbuch der Lokomotiven. Bechtermünz/Weltbild, Augsburg, 1996. ISBN 3-86047-138-4.

- Mück, Wolfgang: Deutschlands erste Eisenbahn mit Dampfkraft. Die kgl. priv. Ludwigseisenbahn zwischen Nürnberg und Fürth. 2nd revised edn. Fürth, 1985, pp. 115–126. (Thesis at the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg 1968)

- Rebenstein, Georg: Stephenson's Locomotive auf der Ludwigs-Eisenbahn von Nuernberg nach Fuerth. Nürnberg 1836.

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For the meaning of this notation, see £sd § Writing conventions and pronunciations.

References

[edit]- ^ Bulletin Archived 2011-12-26 at the Wayback Machine about the Berlin steam locomotive that was to be used in a coal mine in the Saar (German)

- ^ Report on the Berlin steam engine, that was to have been used in a coal mine in the Saar (German) Archived 2012-02-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Markus Hehl: Der "Adler" – Deutschlands erste Dampflokomotive. Weltbild, Augsburg 2008, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d Wolfgang Mück. Deutschlands erste Eisenbahn mit Dampfkraft. Die kgl. priv. Ludwigseisenbahn zwischen Nürnberg und Fürth. Fürth 1985, p. 115–126.

- ^ Peter Heigl. Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, pp. 37–38

- ^ Peter Heigl. Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg, 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 30

- ^ Peter Heigl: Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 25–26.

- ^ Georg Rebenstein: Stephenson's Locomotive auf der Ludwigs-Eisenbahn von Nuernberg nach Fuerth. Nuremberg, 1836.

- ^ Ulrich Scheefold: 150 Jahre Eisenbahnen in Deutschland. Munich, 1985, p. 9.

- ^ Peter Heigl: Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 54.

- ^ Adler_home.html Der "Adler". Archived 2009-03-01 at the Wayback Machine auf: Nürnberg online.

- ^ Peter Heigl: Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 57–59.

- ^ Peter Heigl: Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 69.

- ^ Peter Heigl: Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 77 ff.

- ^ Peter Heigl: Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 99–123.

- ^ "Rückkehr des Adler". In: Eisenbahn-Revue International. Heft 11, Jahrgang 1999, ISSN 1421-2811, p. 456f.

- ^ Peter Heigl: Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 125

- ^ eisenbahn magazin 1/2008, p. 9

- ^ "Nürnberger News of 24.10.2007". Archived from the original on 2008-01-13. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ Adler_191007/ta.wissenschaft.diashow.Adler_191007.frameset.php Photo gallery on the subject "Adler wieder unter Dampf" ('Adler in steam again')[permanent dead link] Thüringer Allgemeinen newspaper of 24.10.2007

- ^ Reconstruction of the historic "Adler" train has started

- ^ Peter Heigl: Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 148.

- ^ Peter Heigl: Adler – Stationen einer Lokomotive im Laufe dreier Jahrhunderte. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-935719-55-1, p. 73.