Glen Affric

| Glen Affric National Nature Reserve | |

|---|---|

Pinewoods at Loch Beinn a' Mheadhoin | |

| Location | Cannich, Highland, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 57°14′09″N 5°09′12″W / 57.23596°N 5.15327°W |

| Area | 145 km2 (56 sq mi)[2] |

| Designation | NatureScot |

| Established | 2002[3] |

| Operator | Forestry and Land Scotland |

| Glen Affric National Nature Reserve | |

Glen Affric (Scottish Gaelic: Gleann Afraig)[4] is a glen south-west of the village of Cannich in the Highland region of Scotland, some 15 miles (25 kilometres) west of Loch Ness. The River Affric runs along its length, passing through Loch Affric and Loch Beinn a' Mheadhoin. A minor public road reaches as far as the end of Loch Beinn a' Mheadhoin, but beyond that point only rough tracks and footpaths continue along the glen.[5]

Often described as the most beautiful glen in Scotland, Glen Affric contains the third largest area of ancient Caledonian pinewoods in Scotland, as well as lochs, moorland and mountains.[6] The area is a Caledonian Forest Reserve,[7] a national scenic area and a national nature reserve, as well as holding several other conservation designations.[8]

The forests and open landscapes of the glen, and the mountains on either side, are a popular destination for hikers, climbers and mountain bikers.[9]

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Glen Affric is listed in the Caledonian Pinewood Inventory,[7] and contains the third largest area of ancient Caledonian pinewoods in Scotland.[6] Due to the importance of this woodland it has been classified as a national nature reserve since 2002, and holds several other conservation designations.[8] The pinewood consists predominantly of Scots pine, but also includes broadleaved species such as birch, rowan, aspen, willows and alder. The forest floor hosts many plant species typically found in Scotland's pinewoods, including creeping ladies tresses, lesser twayblade, twinflower, and four species of wintergreen. Many nationally rare or scarce species of lichens grow on the trees of Glen Affric.[10]

Scots pine trees first colonised the area after the last Ice Age, 10,000 to 8,000 years ago. Currently the oldest trees in the area are the gnarled "granny" pines that are the survivors of generations of felling. Although felling ceased many years ago, regrowth was hampered by unnaturally high populations of sheep and deer, and in the early 1950s the Forestry Commission found that very few of the remaining pines were less than 100 years old.[11] Initially the Commission, which was tasked with increasing the total amount of tree cover without reference to the species used, reforested the area with non-native species such as Sitka spruce and lodgepole pine, as well as Scots pine from local seed stocks. Since the 1980s management priorities have changed, and non-native conifers have been felled and removed from the glen, alongside the removal of other non-native trees such as rhododendron. Some commercial forestry continues in order to maintain forest cover and to benefit local people financially, and considerable areas of non-native conifers are expected to remain in the forest over the next few decades.[12][13]

Forestry and Land Scotland (successor body to the Forestry Commission) aims to encourage regrowth of the pinewood by reducing deer numbers, thus minimising the use of fencing, which can injure black grouse and capercaillie which collide with the wires.[14] The long-term aim is to provide a network of forest habitats, with corridors of new forest linking existing woodland, interspersed with open areas. Management of the reserve also seeks to establish a 'treeline transition zone', in which there is a more gradual transition between woodland and mountain heath with an intermediate zone of shorter, more twisted trees and low-growing shrubs.[13] At the western end of the glen the National Trust for Scotland aims to encourage the growth of other tree species such as birch and rowan to complement the pinewood lower down the glen.[15] The charity Trees for Life have also planted extensively in Glen Affric, in areas once grazed by deer. They own a bothy at Athnamulloch, by the edge of Loch Affric, that is used to house volunteers.[16]

After nearly seventy years of management to encourage restoration of the area, biodiversity has improved and Glen Affric now supports birds such as black grouse, capercaillie, crested tit and Scottish crossbill, as well as raptor species such as ospreys and golden eagles. Glen Affric is also home to Scottish wildcats and otters. The bogs and lochs of the glen provide a habitat for many species of dragonfly, including the rare brilliant emerald.[11][10][17]

In 2019 an elm tree in Glen Affric, christened the "Last Ent of Affric" was named Scotland's Tree of the Year by the Woodland Trust.[18]

History

[edit]

Glen Affric, also written Glenaffric,[19] was part of the lands of the Clan Chisholm and the Clan Fraser of Lovat from the 15th to the mid 19th centuries. By the early 15th century, Lord Lovat had passed the lands to his son Thomas who in turn passed it on to his son, William, who was recorded in Burke's Landed Gentry Scotland as William Fraser, first Laird of Guisachan.[20][21] In 1579, Thomas Chisholm, Laird of Strathglass, was imprisoned for being a Catholic.[22] By the 18th century, the title deeds of Glen Affric had been a source of feuding, with the Battle of Glen Affric taking place in 1721.[23]

Dudley Marjoribanks, later Lord Tweedmouth was a rich Liberal MP who took a long lease on shooting rights over much of Glen Affric in 1846 and, by 1856, had acquired ownership of the Glen Affric Estate from "Laird Fraser" whose family had built the original Guisachan Georgian manor house around 1755.[24][25][26] The estate held over 13,000 hectares (32,000 acres) at the time of its transference from the Clan Chisholm to Lord Tweedmouth.[27][28] By the 1860s, Lord Tweedmouth, as the new laird, had much enlarged the house,[29] using Scottish architect Alexander Reid who designed many buildings on Tweedmouth's vast Glen Affric Estate, including an entire village—Tomich—and the Glen Affric Hunting Lodge,[30] described in appearance as "castle-like".[31] Tweedmouth had enjoyed shooting rights over much of Glen Affric since 1846, and, following his acquisition of the estate he initiated the first breed of golden retrievers at kennels near Guisachan House. He put the retrievers to good use at the shooting parties he hosted when at Glen Affric Lodge. The retrievers were sent to other estates when, for some months of the years 1870–71, he leased the Glen Affric Estate to Lord Grosvenor.[32][33][34]

In 1894 Edward Marjoribanks, 2nd Baron Tweedmouth had inherited the Glenaffric and Guisachan estates from his father. His wife, the Baroness Tweedmouth, was born Lady Fanny Spencer-Churchill, the daughter of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, and died at Glen Affric Lodge in 1904.[35] Known in the highlands as the Lady of Glenaffric and Guisachan, she was reported to be a "lover of the golden retriever dog".[36]

The Duke and Duchess of York are reported in The Graphic, 25 September 1897 to have visited the Guisachan Estate in Strathglass, including Glen Affric Lodge. Lady Tweedmouth's nephew Winston Churchill also came to visit the estate in 1901, and amused himself learning how to drive a car in the grounds.[37][38][39]

Clan Marjoribanks' ownership ended with Edward’s son, Dudley Churchill Marjoribanks, who became 3rd Lord Tweedmouth in 1909. He and his wife had two daughters, but no male heir. For the next few years, until 1918, the estate was owned by the family of Newton Wallop, 6th Earl of Portsmouth (1856–1917).[40] Marmaduke Furness, 1st Viscount Furness owned the estate throughout the 1920s and 30s.[41] The entire property, then consisting of 22,000 acres (8,900 ha), had been sold by 1936 to a Mr Hunter. It was he who resold the Glen Affric deer forest to the west and a large area of grazing land to the Forestry Commission.[42][43]

Lady Islington acquired the Guisachan portion of the estate in 1939 but let the property go to ruin. In 1962 the Guisachan estate was bought by a descendant of the Frasers of Gortuleg. In 1990, this later generation laird wrote a booklet concerning his Fraser ancestors who had once owned Guisachan—Guisachan, A History by Donald Fraser.[33][44][45][46]

Provost Robert Wotherspoon was recorded as owning Glen Affric Estate in 1951, having purchased it in 1944 and selling the "majority of its ground to the Forestry Commission" in 1948.[47][48] His son, Iain Wotherspoon was listed as living at Glen Affric Lodge in 1958.[49]

Glen Affric tartan

[edit]

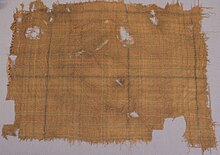

In April 2023, a fragment of cloth known as the "Glen Affric tartan" went on display at the V&A Dundee museum, on loan from the Scottish Tartans Authority. The tartan, which measures 55 cm × 42 cm (22 in × 17 in), contains faded colours including green, brown, red, and yellow. Discovered in the early 1980s in a peat bog near Glen Affric, it is dated to approximately 1500–1600 AD making it Scotland's "oldest-known true tartan", having been preserved in the bog for over 400 years.[50][51]

In January 2024, a group of tartan experts announced that they had recreated the tartan, with the assistance of dye analysis, carbon-14 dating and a detailed study of the original cloth fragment.[52]

Current ownership

[edit]

Most of the glen was bought by the Forestry Commission in 1951. Although the House of Commons recorded that the Commission was considering returning at least some of its Glen Affric landholdings to private ownership in the early 1980s,[53][54][55] the majority of the glen continues to form part of Scotland's National Forest Estate. The Forestry Commission's successor body, Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS), is the largest single landowner in Glen Affric, holding 176 square kilometres (68 sq mi) of the lower and central parts of the glen.[56][57]

The National Trust for Scotland has owned the 37 km2 (14 sq mi)[58] West Affric Estate,[59] which covers the upper part of the glen,[57] since 1993.[60]

As of 2019 the main private landowner is the North Affric Estate with 36 km2 (14 sq mi) of land on the north side of Loch Affric centred on the baronial Affric Lodge.[57][61][45][31] Since 2008 this land has been held by David Matthews, father-in-law of Pippa Middleton.[62][21][42]

The Guisachan area of Glen Affric, which lies to the south of the main glen, is also in private hands, now forming three separate estates. Wester Guisachan Estate covers 38 km2 (15 sq mi) of land to the south of Loch Affric,[63] whilst the Hilton & Guisachan Estates, owned by Alexander Grigg, lies further east and covers 17 km2 (6.6 sq mi).[64] The final portion of the Guisachan Estate, which is in the ownership of Nigel Fraser, consists of 7 km2 (2.7 sq mi) at the very east of the glen. In this area lies the Conservation village of Tomich.

As with all land in Scotland, there is a right of responsible access to most of the land in the glen for pursuits such as walking, cycling, horse-riding and wild camping. These rights apply regardless of whether the land is in public or private ownership, provided access is exercised in accordance with the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.[65]

Tourism

[edit]

Glen Affric is popular with hillwalkers, as it provides access to many Munros and Corbetts. The north side of the glen forms a ridge with eight Munro summits, including the highest peak north of the Great Glen, Càrn Eige 1,183 m (3,881 ft).[66] The three Munros at the western end of this ridge, Sgùrr nan Ceathreamhnan 1,151 m (3,776 ft), Mullach na Dheireagain 982 m (3,222 ft) and An Socach 921 m (3,022 ft), are amongst the remotest hills in Scotland, and are often climbed from the Scottish Youth Hostels Association hostel at Alltbeithe.[66] The hostel is only open in the summer, and can only be reached by foot or by mountain bike via routes of between 10 and 13 km (6.2 and 8.1 mi) starting from lower down Glen Affric or from the A87 at Loch Cluanie or Morvich. The dormitories are unheated and hostellers are required to bring a sleeping bag, and to carry out all rubbish.[67] Three miles (five kilometres) east of the hostel is the Strawberry Cottage mountaineering hut, maintained by the An Teallach Mountaineering Club, described by The Scotsman as "one of the best-equipped huts in the country".[68] Glen Affric is also the starting point for routes to the summits of Munros to the south and west of the glen, although these can also be accessed from the Kintail area.[66] Corbetts accessible from Glen Affric include Sgùrr Gaorsaic, Càrn a' Choire Ghairbh and Aonach Shasuinn.[69]

The Affric Kintail Way is a 70 km (43 mi) long route from Drumnadrochit on the shore of Loch Ness to Morvich in Kintail via Glen Urquhart and Glen Affric. The route is suitable for both walkers and mountain bikers, and can usually be walked in four days.[70][71]

Shorter waymarked trails are provided in the lower parts of the glen, taking walkers to viewpoints and attractions such as the waterfalls at Plodda and the Dog Falls.[72]

Hydro-electric scheme

[edit]

The glen is part of the Affric/Beauly hydroelectric scheme, constructed by the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board. Loch Mullardoch, in the neighbouring Glen Cannich, is dammed, and a 5 km (3.1 mi) tunnel carries water to Loch Beinn a' Mheadhoin, which has also been dammed. From there, another tunnel takes water to Fasnakyle power station, near Cannich. As the rivers in this scheme are important for Atlantic salmon, flow in the rivers is kept above agreed levels. The dam at Loch Beinn a' Mheadhoin has a Borland fish ladder to allow salmon to pass.[73]

Conservation designations

[edit]In addition to being a national nature reserve, Glen Affric is a Caledonian Forest Reserve,[7] a National Scenic Area,[74] and a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).[75] The NNR is classified as a Category II protected area by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[1] Much of the area forms part of a European Union Special Protection Area for golden eagles,[76] and is also classified as an EU Special Area of Conservation.[17]

Glen Affric was proposed for inclusion in a national park by the Ramsay committee, set up following the Second World War to consider the issue of national parks in Scotland,[77] and in 2013 the Scottish Campaign for National Parks listed the area as one of seven deemed suitable for national park status,[78] however as of 2019 no national park designation has occurred. In September 2016 Roseanna Cunningham, the Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform, told the Scottish Parliament that the Scottish Government had no plans to designate new national parks in Scotland and instead planned to focus on the two existing national parks.[79]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Glen Affric". Protected Planet. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "Glen Affric NNR". NatureScot. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Glen Affric – Setting the Scene". Scottish Natural Heritage. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Forestry Commission 2013" (PDF). Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba. 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ Ordnance Survey 1:50000 Landranger Sheet 25, Glen Carron and Glen Affric.

- ^ a b "The special qualities of the National Scenic Areas" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "Caledonian Pinewood Inventory". Forestry Commission Scotland. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Sitelink – Map Search". NatureScot. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Humphreys, Rob; Reid, Donald (12 July 2012). The Great Glen Rough Guides Snapshot Scotland (includes Fort William, Glen Coe, Culloden, Inverness and Loch Ness). Rough Guides. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4093-6581-5.

- ^ a b "Glen Affric SSSI Citation". Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Glen Affric – Wood of Ages". Scottish Natural Heritage. 18 November 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Glen Affric Land Management Plan Vision and Summary" (PDF). Forestry and Land Scotland. July 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Glen Affric – Return of the native". Scottish Natural Heritage. 17 November 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Glen Affric – Managing for diversity". Scottish Natural Heritage. 18 November 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "West Affric Estate". National Trust for Scotland. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Planting a vision". The Guardian. 23 October 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Strathglass Complex SAC". NatureScot. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "The 'Last Ent of Affric' is Scotland's Tree of the Year 2019". Forestry and Land Scotland. 23 October 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "Scottish Register of Tartans – Glenaffric Fragment". The Scottish Government – National Records of Scotland, H.M. General Register House. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "Burke's Landed Gentry Scotland". Burke’s Peerage. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ a b Gibson, Rob (2014). Highland Cowboys: From the Hills of Scotland to the American Wild West. Luath Press Ltd. pp. Maps. ISBN 9781909912960.

- ^ "Our Lady and St Bean's Church, Marydale – Strathglass 'Pestered With Popery' & Knockfin". Parish of St Mary, Beauly. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Macrae, A. (1976). "History of the Clan Macrae". Gateway Press. p. 93. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

..... Duncan had valuable papers on his person at the time, and among them the title deeds of Affric.

- ^ "Glen Affric Map Guide" (PDF). Forestry Commission Scotland. p. 2. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

Lord Tweedmouth, a rich brewer and Liberal Member of Parliament bought this area from Laird Fraser in 1856...

- ^ "Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, Volume 54". Inverness Gaelic Society – 1987. 1987. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

.. (he) first rented and then, as Lord Tweedmouth, bought Guisachan and the whole of Knockfin and Glenaffric.

- ^ Gray, Bob (February 2013). "Glen Affric Weekend, 9–10th June 2012" (PDF). Glasgow Natural History Society Newsletter: 6. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ^ The Deer Stalking Grounds of Great Britain and Ireland. Hollis and Carter. 1960.

In 1913, Millais listed no less than eight forests in this area belonging to the Chisholms: Affric (32,000 acres), Benula (20,000 acres), Erchless (8,000 acres), Fasnakyle (25,000 acres), Glencannich (13,000 acres), Knockfin (8,000 acres), ...

- ^ "Glen Affric". 2019 Forestry and Land Scotland. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

Sir Dudley Coutts Marjoribanks, the first Lord Tweedmouth, was a rich Liberal MP who took a long lease on shooting rights over much of Glen Affric in 1846, paying £3,000 per year for the privilege: about £130,000 in today's money

- ^ "DSA Building/Design Report – Guisachan House". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "DSA Building/Design Report – Glen Affric Lodge – (1860-c1871) Architects – A & W Reid". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ a b Campbell, Kieran (29 October 2014). "Inside world's most exclusive holiday retreats – (Glen Affric Estate)". The Australian.

- ^ "Highlands' own little piece of Eden". The Scotsman. 8 January 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Strathglass". Strathglass Marketing. Strathglass Marketing Group. 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Morphet, M. N. (2011). "Golden Retrievers ~ Research Into the First Century in the Show Ring" (PDF). Tweedsmouth Publishing. pp. 62–3. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Mack, Ann (17 May 2017). "History repeats itself with the two Lady Glen Affrics". Press and Journal. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Melhuish, A. (1876). "Fanny Octavia Louisa (née Spencer-Churchill)". London National Portrait Gallery. A.J. (Arthur James) Melhuish. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Strong-Boag, Veronica (2015). Liberal Hearts and Coronets: The Lives and Times of Ishbel Marjoribanks Gordon and John Campbell Gordon, the Aberdeens. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442626027. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ Weir, Tom (2016). Tom Weir – Men of the Trees. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

A Glen With Connections: Fate, however, had something in store for a young man who came here to visit his aunt, wife of the second Lord Tweedmouth. Her name was Lady Fanny Spencer Churchill, and the name of her nephew who came in 1901 was Winston, who amused himself learning how to drive a car in these grounds.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Long, Phil; Palmer, Nicola J. (2008). Royal Tourism: Excursions Around Monarchy. Channel View Publications. p. 76. ISBN 9781845410803.

- ^ "The Earl and Countess Portsmouth have arrived at in the heart of Glen Affric, which Lord Portsmouth bought from Lord Tweedmouth some..." Aberdeen Press and Journal. Aberdeenshire, Scotland. 7 August 1911. Retrieved 6 August 2019 – via Genes Reunited.

The Earl and Countess Portsmouth have arrived at Guisachan in the heart of Glen Affric, which Lord Portsmouth bought from Lord Tweedmouth some years ago. They motored from ...

- ^ Pearson, H. (27 February 2018). The Marrying Americans. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 9781787209572. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ a b Rutland, Tom; Rutland, Sarah. "Breed History – The Day We Met Dileas". Golden Retriever Club of America. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Pepper, Jeffrey G. (2012). Golden Retriever. i5 Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 9781621870340.

- ^ "The Frasers of Guisachan". Bernard Poulin & Bernard Poulin. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Glen Affric, In a Nutshell". böetic. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Welcome to the Friends of Guisachan". Friends of Guisachan. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ The Deer Stalking Grounds of Great Britain and Ireland. Hollis and Carter. 1960.

(page 120) - Glen Affric was one of the Chisholm's forests until 1944 when it was purchased by Provost Robert Wotherspoon. Subsequently, in 1948 he had sold the majority of its ground to the Forestry Commission being granted by the commission a lease of the sporting and grazing rights which lease was to be continued in favour of his family.

- ^ "Is Forestry a Growing Investment?". Country Life: 160. 1984. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

The recent sale of the 25,000-acre Glen Affric Estate, near Inverness, is by far the largest by the [Forestry] Commission. ... a solicitor, Ian Wotherspoon, whose father [Provost Robert Wotherspoon] owned it until 1951.

- ^ Scottish Birds. Edinburgh : Scottish Ornithologists' Club. 1958. LCCN 64028211.

... of the Forestry Commission and Mr Iain Wotherspoon, Glen Affric Lodge.

- ^ "Scotland's oldest tartan discovered by Scottish Tartans Authority". V&A Dundee. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

The Glen Affric tartan, which measures around 55cm by 43cm is due to go on display for the first time at V&A Dundee's Tartan exhibition opening on Saturday 1 April [2023]. New scientific research has revealed a piece of tartan found in a peat bog in Glen Affric around forty years ago can be dated to circa 1500-1600 AD, making it the oldest known surviving specimen of true tartan in Scotland.

- ^ Killgrove, Kristina (1 April 2023). "Oldest Scottish tartan ever found was preserved in a bog for over 400 years". Live Science. Future US. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Moloney, Charlie (22 January 2024). "Oldest known Scottish tartan 'brought back to life' for people to wear". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "Parliamentary Debates (Hansard): House of Commons Official report". 50. H.M. Stationery Office. 1983. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

House of Commons Official report Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. [Mr. Archy Kirkwood] crystalised in a recent properly carried out lobby... the market to take over to such an extent that more assets are having to be sold such as Glenelg, and Glen Affric, without proper consultation? ...

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Country Life, Volume 175". Country Life, Limited, 1984: 160. 1984. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

The recent sale of the 25,000-acre Glen Affric Estate, near Inverness, is by far the largest by the [Forestry] Commission.

- ^ "New Scientist". Reed Business Information. 10 November 1983. p. 426. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

..urge the Secretary of State for Scotland to prevent the Forestry Commission from returning 35,000 acres of Glen Affric to private ownership....once back in private hands, Affric could be sold off by the previous owners, the Wotherspoon family, to Arab sheikhs or Dutch speculators, who have denied the public access ...

- ^ "Restoring native woodland in Glen Affric". Forestry Commission Scotland. 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "Property Search". Who Owns Scotland. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ "Property Page: West Affric Estate". Who Owns Scotland. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ West Affric - on homepage of NTS access-date= 8 August 2021

- ^ National Trust for Scotland 2017 Guide, p. 97.

- ^ "Property Page: North Affric Estate". Who Owns Scotland. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Ramage, I. (22 July 2016). "Pippa could be Lady of Glen". The Press and Journal (Inverness, Highlands and Islands). Retrieved 31 August 2019.

...[Pippa] Middleton is marrying James Matthews, the eldest son of David Matthews, the Laird of the glorious Glen Affric Estate...

- ^ "Property Page: Wester Guisachan Estate". Who Owns Scotland. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Property Page: Hilton & Guisachan Estate". Who Owns Scotland. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Scottish Outdoor Access Code" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ a b c D. Bennet & R. Anderson. The Munros: Scottish Mountaineering Club Hillwalkers Guide, pp. 178–195. Published 2016.

- ^ "Glen Affric Youth Hostel". Scottish Youth Hostels Association. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Back to Glen Affric for an easy lochside walk". The Scotsman. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ R. Milne & H Brown. The Corbetts and Other Scottish Hills – Scottish Mountaineering Club Hillwalkers' Guide, pp. 182–185. Published 2002.

- ^ "About The Affric Kintail Way". Strathglass Marketing Group. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Route Overview". Strathglass Marketing Group. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Glen Affric Map and Guide" (PDF). Forestry Commission Scotland. March 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Power From the Glens" (PDF). Scottish and Southern Energy. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ "Glen Affric NSA". NatureScot. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Glen Affric SSSI". NatureScot. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Glen Affric to Strathconon SPA". NatureScot. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "History Leading to the Cairngorms National Park". Cairngorms National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Unfinished Business a national parks strategy for scotland" (PDF). Scottish Campaign for National Parks. March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "Scottish Government "short sighted" over snub to national park for Galloway". Dumfries and Galloway – What's Going On. 16 September 2016. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.