alt attribute

| HTML |

|---|

| Comparisons |

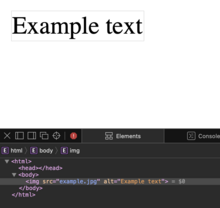

The alt attribute is the HTML attribute used in HTML and XHTML documents to specify alternative text (alt text) that is to be displayed in place of an element that cannot be rendered. The alt attribute is used for short descriptions, with longer descriptions using the longdesc attribute. The standards organization for the World Wide Web, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), recommends that every image displayed through HTML have an alt attribute, though the alt attribute does not need to contain text. The lack of proper alt attributes on website images has led to several accessibility-related lawsuits.

The alt attribute is used to increase accessibility and user friendliness, including for blind internet users who rely on special software for web browsing. The use of the alt attribute for images displayed within HTML is part of W3C's Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). Screen readers and text-based web browsers read the alt attribute in place of the image. The text within the alt attribute substitutes the image when copy-pasted as text and makes images more machine-readable, which improves search engine optimization (SEO).

History

[edit]The attribute was first introduced in the HTML 1.2 draft in 1993 to provide support for text-based browsers.[1] In HTML 4.01, which was released in 1999, the attribute was made to be a requirement for the img and area tags.[2] It is optional for the input tag and the deprecated applet tag.[3]

Internet Explorer 7 and earlier render text in alt attributes as tooltip text, which is not compliant with the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C)'s HTML standards.[4] This behavior led many web developers to misuse the alt attribute when they wished to display tooltips containing additional information about images, instead of using the title attribute that was intended for that use.[5][6] As of Internet Explorer 8, released in 2009, alt attributes no longer render as tooltips on Internet Explorer.[7]

Usage

[edit]

The text in the alt attribute is used to replace the image when the image cannot be loaded, without changing the intended meaning of the page's contents.[8] The W3C's web content accessibility guidelines state that the alt attribute is used to convey the meaning and intent of the image, rather than being a literal description of the image itself.[9] For example, an alt attribute for an image of an institution's logo should convey that it is the institution's logo rather than describing details of what the logo looks like.[10][11] The alt attribute is intended to be used for short and concise descriptions of the image. Longer descriptions can be given using the longdesc attribute, which provides more detailed information and complements but does not replace the alt attribute.[2]

A screen reader such as Orca will read out the alt text in place of the image.[12] A text-based web browser such as Lynx will display the alt text instead of the image (or will display the value attribute if the image is a clickable button).[13] A graphical browser typically will display only the image, and will display the alt text only if the user views the image's properties, or has configured the browser not to display images, or if the browser was unable to retrieve or to decode the image.[14]

The use of descriptions in the alt attribute improves search engine optimization and allows image-specific search engines, such as Google Images, to search for and display relevant images that are used on websites in search results.[15] For non-image search results, the text within the alt attribute is read by search engines the same way that regular text on the page is read.[16]

The W3C recommends that images that convey no information, but are purely decorative, be specified in CSS rather than in the HTML markup. If decorative images are rendered using HTML that do not add to the content and provide no additional information, then the W3C recommends that a blank alt attribute be included in the form of alt="".[17] This makes the page more navigable for users of screen readers or non-graphical browsers by skipping over images that do not convey any meaning. If no alt attribute has been supplied, then browsers that cannot display the image will not overlook the image but instead will read or display the URL or another identifying marker.[18] This creates ambiguity since the user is generally unable to determine from a bare reading of a URL if the image is relevant to the text or if it is a purely decorative element of the webpage.[19] A 2021 Google Lighthouse audit showed that 27% of alt text attributes audited were empty, despite the fact that the majority of those images were non-decorative informational images.[20]

Lawsuits

[edit]There have been many lawsuits over website accessibility and the lack of proper alt attributes on websites.[18] Maguire v Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games was a 2000 lawsuit in which a blind man in Australia sued the Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games because their website www.olympics.com was not accessible to him because of the lack of alt attributes on images.[21] The Australian Human Rights Commission ruled that the website had discriminated against him for failing to conform to accessibility standards that enable blind individuals to navigate websites.[22] During the lawsuit, the Australian commonwealth, state and territory governments issued a joint statement through the Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy that they were adopting the W3C's accessibility guidelines for all .gov.au websites.[23]

In the United States, there have been several high-profile lawsuits involving the lack of alt attributes on images that cite a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).[24] The United States Department of Justice gives the lack of alt attributes as an example of a barrier to website accessibility.[25] National Federation of the Blind v. Target Corp. was a 2006 class-action lawsuit that alleged that Target.com violated the ADA because the images did not use alt attributes.[26] This lawsuit set a legal precedent in the United States for website accessibility and compliance with the ADA.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ Berners-Lee, Tim; Connolly, Daniel (June 1993). "Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) Internet Draft version 1.2". IETF IIIR Working Group. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ a b "13 Objects, Images, and Applets". World Wide Web Consortium. 24 December 1999. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2005.

- ^ Hazaël-Massieux, Dominique (20 November 2002). "Use the alt attribute to describe the function of each visual". World Wide Web Consortium. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Why doesn't Mozilla display my alt tooltips?". MDN Web Docs. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Flavell, A.J. "Use of ALT texts in IMGs". www.htmlhelp.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ W3C HTML WG (24 December 1999). "7.4.3 The title attribute". HTML 4.01 Specification. W3C. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "What's New in Internet Explorer 8 – Accessibility and ARIA". MSDN. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "HTMLImageElement.alt". Mozilla. Archived from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Using alt attributes on img elements". World Wide Web Consortium. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ "Logo Alt Text". University of South Carolina. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Montti, Roger (1 November 2022). "Google Explains Alt Text for Logos & Buttons". Search Engine Journal. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Hofmann, Frank; Beckert, Axel (2021). "Text Art: Rendering images as text". Linux Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Lynx Users Guide v2.8.9". lynx.invisible-island.net. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ "Image ALT Text". Pennsylvania State University. 6 October 2014. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Google Images best practices". Google Developers. 20 September 2022. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Southern, Matt G. (22 March 2022). "Google: Alt Text Only A Factor For Image Search". Search Engine Journal. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Embedded content – HTML 5". W3C. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ a b Solovieva, Tatiana I.; Bock, Jeremy M. (2014). "Monitoring for Accessibility and University Websites: Meeting the Needs of People with Disabilities". Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability. 27 (2): 113–127. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022 – via Education Resources Information Center.

- ^ Curl, Angela L.; Bowers, Deborah D. (23 April 2009). "A Longitudinal Study of Website Accessibility: Have Social Work Education Websites Become More Accessible?". Journal of Technology in Human Services. 27 (2): 93–105. doi:10.1080/15228830902749229. hdl:2374.MIA/5279. S2CID 143667951. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Tait, Alex; Davis, Scott; Niyi-Awosusi, Olu; Wilhelm, Gary; Dixon, Carlie (30 November 2021). "Part II Chapter 9 – Accessibility". Web Almanac by HTTParchive.org. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ White, Caroline (2 November 2000). "Battle to be equal". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Barkham, Patrick (30 August 2000). "Website 'discriminated against blind'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Seventh Ministerial meeting of the Online Council – Media release". Australian Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy. 30 June 2000. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Alex H.; Fresneda, Jorge E.; Anderson, Rolph E. (September 2020). "What retailers need to understand about website inaccessibility and disabled consumers: Challenges and opportunities". Journal of Consumer Affairs. 54 (3): 854–889. doi:10.1111/joca.12307. ISSN 0022-0078. S2CID 225771708.

- ^ "Guidance on Web Accessibility and the ADA". ADA.gov. 18 March 2022. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Daniels, Linda Markus (13 September 2006). "Websites for the Blind: Is This The Next 'Year 2000 Compliant' Requirement?". WRAL-TV. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Frank, Jonathan (January 2008). "Web Accessibility for the Blind: Corporate Social Responsibility or Litigation Avoidance?". Proceedings of the 41st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS 2008). Waikoloa, HI: IEEE. p. 284. doi:10.1109/HICSS.2008.497. S2CID 16280255. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2022.