Harrison family of Virginia

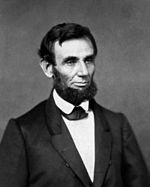

The Harrison family of Virginia is an American family with a history in politics, public service, and religious ministry, beginning in the Colony of Virginia during the 1600s. Family members include a Founding Father of the United States, Benjamin Harrison V, and three U. S. presidents: William Henry Harrison, Benjamin Harrison, and Abraham Lincoln.[a] Some Harrisons have served as state and local public officials and others have been instrumental in education and medicine. Musician and actor Elvis Presley is also in their number.

The Virginia Harrisons comprise two branches, both with origins in northern England. One branch was led by Benjamin Harrison I, who journeyed from Yorkshire by way of Bermuda to Virginia before 1633 and eventually settled on the James River at Berkeley Plantation; he and his descendants are often referred to as the James River Harrisons. Successive generations of this part of the family served in the legislature of the Colony of Virginia. Benjamin Harrison V also served in the Continental Congress, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and later was Governor of Virginia.

The James River branch produced President William Henry Harrison, Benjamin V's son, and President Benjamin Harrison, William Henry's grandson, as well as another Virginia governor, Albertis Harrison.[b] Descendants of the James River family include two Chicago mayors and members of the U.S. Congress. Sarah Embra Harrison of Danville, Virginia launched a decades-long church ministry, the "Pass-It-On Club", in the midst of the Roaring Twenties.

The second branch of the Virginia Harrisons was led by Isaiah Harrison, who immigrated to New England in 1687 from Durham, England. He and his family settled in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia in 1737. Isaiah was most likely the son of Rev. Thomas Harrison, who served as chaplain of the Jamestown Colony. Thomas was kindred to the James River Harrisons, though by 1650 he had returned to England and had a parish in London, before later moving to Ireland.

As members of the Virginia planter class, early generations of the Harrisons included slaveholders. President Abraham Lincoln, who descended from the Shenandoah Valley family, was credited with measures to eliminate slavery in the nation; with abolition following the Civil War, the Harrisons eventually abandoned the institution.

Also among the Valley Harrisons were founders of the Virginia towns of Harrisonburg and Dayton. Other family members included Elvis Presley, the "King of Rock and Roll", as well as educators who were active in the areas of linguistics and women's advocacy. A number of the Harrisons chose medicine, including urologist Hartwell Harrison, who in 1954 collaborated in the world's first successful kidney transplant, as the donor's surgeon.

English origin

[edit]Several genealogists indicate the first Harrisons were Viking warriors of Norse origin, and that they arrived in northeast England with Cnut the Great; others say they are of Celtic descent. Harrisons are indeed found in early Yorkshire and Durham, in northern England. Some in their number used the older spelling "Harryson" ("son of Harry"), although this mostly ended with their arrival in the New World.[3] Among the earliest family was Thomas Harrison (1504–1595) who was the Mayor of York, England.[4]

The two Virginia Harrison lines share similar coats of arms, both issued in English heraldry. They feature helmets and shields emblazoned by gold eagles on a dark field with supporters. The arms of William Henry Harrison (1773–1841), of the James River Harrisons, are sourced to Yorkshire; they depict three eagles and are mentioned in the arms of "Harrison of the North", granted in England in 1574, as well as those of "Harrison of London", granted in 1613 with a pedigree dating from 1374. They are often referred to as the "Yorkshire arms". The crescent below the helmet denotes a second eldest son, as in the case of William Henry.[5]

The "Durham arms" were used by Daniel Harrison of the Shenandoah Valley Harrisons, featuring one eagle and sourced to Harrisons descended from Durham. Included is the crest shoulder gules (red) signaling strength or martyrdom. These arms were first established by the pedigree of Robert Harrison in 1630, showing him to be the grandson of Rowland Harrison of Barnard Castle in Durham.[6]

James River family

[edit]

homestead of the James River Harrisons

Multiple sources indicate the James River Harrisons first appeared in the Colony of Virginia soon after 1630, when Benjamin Harrison I (1594–1648) left London for America by way of Bermuda.[7][8][9][10] Author J. Houston Harrison references the tradition, supported by other writers, that Benjamin had four brothers: Thomas, who also ended up in the south, Richard and Nathaniel who were in the north, and Edward who remained in England.[11][12][c]

The parentage of the brothers is the subject of several different viewpoints. Genealogist McConathy states the father was Richard Harrison, who descended from Rowland Harrison of Durham.[14] McConathy's work also allows the brothers could have been the sons of Thomas Harrison, Lord of Gobion's Manor (1568–1625), and wife Elizabeth Bernard (1569–1643) of St. Giles, Nottinghamshire, England.[15][16] Still other sources indicate the father was merchant Robert Harrison of Yorkshire.[13][17]

Benjamin Harrison's brother Richard settled in Connecticut Colony, while Nathaniel was in Boston. Thomas (1619–1682) arrived in Virginia in 1640 and was a minister there before returning to England after several years.[18] Benjamin arrived in Virginia by 1633, as he was installed as clerk of the Virginia Governor's Council in that year. In 1642, he became the first of the family to serve as a legislator in the Virginia House of Burgesses.[19] His son Benjamin II (1645–1712) served as county sheriff and in the House of Burgesses, and also was appointed to the Governor's Council, the upper house of the Colony's legislature.[20][d]

The second Benjamin in turn fathered Benjamin Harrison III (1673–1710) who similarly was drafted for public service and leadership, first as acting Attorney General, then Treasurer of the Colony and Speaker of the Burgesses. He acquired Berkeley Hundred from his father who bought it in 1691.[21] Benjamin Harrison IV (1693–1745) became a member of the House of Burgesses, but he did not otherwise pursue politics. He married Anne Carter (1702–1745), daughter of Robert "King" Carter (1662/63–1732), and built the family homestead Berkeley Plantation.[22][e] At age 51, with young daughter Hannah in hand, he was struck by lightning as he shut an upstairs window during a storm on July 12, 1745; both were killed.[25]

"The Signer" and two presidents

[edit]Benjamin Harrison V (1726–1791) followed his father by serving in the House of Burgesses, and then became known in the family as "the Signer" of the Declaration of Independence, from his representation of Virginia in the First and Second Continental Congresses. He was chosen Chairman of the Congress' Committee of the Whole and therefore presided over final deliberations of the Declaration.[7]

Harrison was a rather corpulent and boisterous man; Delegate John Adams referred to him variously as the Congress' "Falstaff", and as "obscene", "profane", and "impious". However, Adams allowed that "Harrison's contributions and many pleasantries steadied rough sessions" and also that Harrison "was descended from one of the most ancient, wealthy, and respectable Families in the ancient dominion."[7]

The genuine and mutual enmity between Adams and Harrison stemmed from Adams' upbringing in aversion to human pleasures and Harrison's appreciation for storytelling, fine food, and wine. There was also a political distaste between them—Adams was too radical for Harrison and the latter was too conservative for Adams. The two therefore had distinctly opposing congressional alliances—Harrison with John Hancock and Adams with Richard Henry Lee.[7]

Harrison was a friend and confidant of fellow-Virginian George Washington; in 1775 he joined Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Lynch on a select committee to help the newly appointed General Washington secure much needed enlistments and supplies for the Continental Army.[7][f] Harrison also served on the Board of War with Adams, and on the Committee of Secret Correspondence with Benjamin Franklin.[7]

Pennsylvania Delegate Benjamin Rush years later recalled the Congress' atmosphere during the signing of the Declaration on August 2, 1776; he described a scene of "pensive and awful silence" which he said Harrison singularly interrupted, when delegates filed forward to inscribe what they thought was their ensuing death warrant. Rush related that Harrison said to the diminutive Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, as the latter was about to sign, "I shall have a great advantage over you, Mr. Gerry, when we are all hung for what we are now doing. From the size and weight of my body I shall die in a few minutes and be with the Angels, but from the lightness of your body you will dance in the air an hour or two before you are dead."[26]

Harrison's family indeed experienced retaliation from the British, like many others, for his role in the revolution. Benedict Arnold and his forces pillaged many plantations, including Berkeley, with the intent of obliterating all images of the treasonous families. In January 1781, the troops removed every family portrait from Harrison's home and made a bonfire of them. Benjamin V later returned to the House of Burgesses and was elected Governor of Virginia (1781–1784).[27][g]

His brother Nathaniel served as sheriff of Prince George County and in the Virginia House as well as the state Senate; he later settled in Amelia County.[28] Nathaniel's son Edmund served as Speaker in the House, and made his home at "The Oaks" in Amelia.[29] The house, which was later disassembled and rebuilt in Richmond, remained in the Harrison family for over 230 years, when it was given to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and served as the home for the sitting Director until 2013.[30]

The "Signer's" son Benjamin Harrison VI (1755–1799) was for a time a successful businessman and also served in the Virginia House of Delegates. His brother was General William Henry Harrison who was also born at Berkeley, and served as a congressional delegate for the Northwest Territory; he was appointed in 1800 as Governor of the Indiana Territory, and served in the War of 1812.[31][32] In the 1840 presidential election, William Henry defeated incumbent Martin Van Buren, but fell ill and died just one month into his presidency; Vice President John Tyler, a fellow Virginian and neighbor, succeeded him.[31] William Henry was the father of Ohio Congressman John Scott Harrison (1804–1878) who was the father of Benjamin Harrison (1833–1901), a brigadier general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.[33] Benjamin also served in the U.S. Senate (1881–1887) and was elected president in 1888 after defeating incumbent Grover Cleveland.[34] According to his national obituaries, Albertis Harrison (1907–1995) was another descendant; he served in the Virginia Senate (1947–1957), was then elected Attorney General of Virginia (1957–1961) and later Governor (1962–1966). He was finally appointed Justice of the Virginia Supreme Court (1968–1981).[35][36][37]

Danville's "Pass-It-On Club" and the tobacco men

[edit]

Sarah Embra Harrison (1874–1935), along with her five brothers, was a descendant of Edmund Harrison of the Oaks. The six siblings descended from Edmund's son, William Henry, and grandson, Rev. J. Hartwell Harrison (1839–1908). (William Henry was a cousin of the president by that name.) They grew up in Amelia County, Virginia, at another family homestead called the Wigwam.[38]

In 1920, Sarah created the "Pass-It-On Club" in Danville, Va., as a ministry to facilitate Sunday church attendance by out-of-town salesmen.[39] The doldrums of these men, stuck for a day in a strange town, came to her attention one Sunday as she entered a hotel lobby for a ladies group lunch. Leaving the hotel, Harrison paused and asked one of the men, "Do you all ever attend church on your visits here?" The man said no such invitation had ever been extended to him in his eight years of travel across the country. She decided to make a plan to remedy that.[40]

Harrison related that, "I went to several of my friends and asked them for their advice and help. Many of those I consulted said my plan was very fine, but that it wouldn't work out. 'Those men don't want to go to church. They will laugh you out of the hotel when you ask them,' they told me. But I had confidence in the men, and in my plan of attack."[40] Soon, with some admitted trepidation, she appeared on a Sunday in the hotel lobby. "Before I knew what had happened, every man in the lobby — there were 11 in all — was in one of the cars I had commandeered, and we were off to the church." When we filed into the church that night, all eyes were upon us; but I didn't mind the neighbors thinking I was a little crazy. And what a joy, as some of those men had not seen a hymn book in years."[40] The church service was followed by a social hour with refreshments with Harrison and her friends at her home.[40]

Harrison promised the men future arrangements for travel to church, and registered them as the first members of the official "Pass It On Club." The club succeeded not only with church attendance, but also placed hundreds of books and magazines in Danville's hotels, and as well helped travelers fallen ill and stranded in Danville. After seven years, in the midst of the Roaring Twenties, based on her roll of club members, The American Magazine declared in a 1927 headline that, "Sarah Harrison Has Taken 4000 Traveling Men to Church".[40]

Sarah had three younger brothers, all of Richmond, Virginia, who were leaders in the tobacco industry in the mid-20th century. Robert C. Harrison (1881–1959) was chairman and CEO of the British American Tobacco Co., Fred N. Harrison (1887–1972) was likewise the head of Universal Leaf Inc., and Joseph H. Harrison (1879–1942) was with the American Tobacco Company. The latter’s grandson Joseph (1957–2024) was a published poet in Baltimore, MD. Another younger brother of Sarah, James D. Harrison (1889–1972), was the leader of the First National Bank of Baltimore. Sarah's older brother, Isaac Carrington Harrison (1870–1949), was a physician in Danville, and served as chairman of the Virginia Board of Medical Examiners.[38]

| James River Harrison family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Harrisons in the Shenandoah Valley

[edit]The Harrisons who settled in the Shenandoah Valley in the 1730s came from New England and likely had common ancestry with the James River family, considered to have descended from Thomas Harrison (1619–1682). He led a parish at Elizabeth River at age 21, and was appointed by Governor William Berkeley as an acting chaplain of the Jamestown Colony.[41]

Rev. Thomas Harrison

[edit]Thomas earned his B.A. from Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge in 1638, then sailed to Virginia in 1640.[17] He was the minister at Elizabeth River Parish and was appointed as the chaplain of Sir William Berkeley. He also served a chaplaincy at Jamestown through the 1644 Indian Massacre there. He became a Puritan and moved to Boston near his brothers, married Dorothy Symonds, and later repatriated to England. In 1650, he had a parish at St. Dunstan-in-the-East, London, and joined the English Puritans. In 1655, then a widower, he became the Chaplain for Henry Cromwell, accompanied him to Ireland, and there resided with the Governor and his family.[13]

Thomas also formed a close friendship with famed author and cleric, Bishop Jeremy Taylor. Taylor biographer Edmund Gosse indicated that Thomas "was rewarded by Governor Cromwell's confidence, and his advice was often asked for and acted upon. When in 1658 he published his extremely popular manual of piety, Topica Sacra, he was the most popular divine in Ireland."[13] Topica Sacra publicized Thomas as a robust and forceful cleric of his time. In an age of piety, the book invokes Job's insistence upon God's answers. Thomas was likewise confrontational in his prayers and, according to Gosse, was willing to "catechize" God for insight into His words. Thomas' work was dedicated to Cromwell and was reprinted on its centennial.[13]

In 1659, he married Katherine Bradshaw and resided in Chester, England. He later settled in Dublin and probably fathered a son named Isaiah in 1666, who was the patriarch of the Virginia Harrisons of the Shenandoah Valley. Thomas died in Dublin in 1682.[42]

J. Houston Harrison cites historian John Peyton who contended that the Valley Harrisons instead descended from Major General Thomas Harrison (1616–1660) who was born in the same year as the Reverend and whose wife was also named Katherine. The General participated in the regicide of King Charles I of England, and was therefore hanged, drawn and quartered in 1660. The Reverend's position as a non-conformist would have made them allies concerning the monarchy, which adds to the confusion of their identities. But no record is found at the Herald's College showing a pedigree and succeeding coat of arms for the General's family, as in the case of the Reverend. Also, no other lineage to the General has been adequately shown, and the notion is therefore discredited.[43]

Isaiah and another president

[edit]

The strongest evidence, though circumstantial for lack of a birth record, is that Reverend Thomas Harrison was the father of Isaiah Harrison (1666–1738), who was born in Dublin at the time of Thomas' residence and marriage there. Thomas' use of the name Isaiah for his son was unique–the name is otherwise non-existent in family records to that time. However, the name was quite in keeping with Puritan and non-conformist beliefs with which Thomas then identified.[44][h]

Isaiah may well have sailed from Dublin for New York in 1687, on the ship The Spotted Calf. His departure, following his father's death, was also a timely consequence of his father's position as a non-conformist. Isaiah Harrison is definitively shown at Oyster Bay on Long Island in 1687—this is the very same area from which his father Thomas had departed on his return to England forty years earlier.[45]

The family of Richard Harrison lived just across Long Island Sound in New Haven, Connecticut. Richard arrived in Connecticut in 1644 and was Isaiah's uncle. John Harrison is shown in Flushing in 1685, and Samuel at Gloucester, New York in 1688.[43] There are records in Dublin which show Thomas' consistent and distinct spelling of Harrison with the double "s", not otherwise found in Ireland or England. Isaiah and his children utilized this same spelling in their American court records.[44][46]

Isaiah's first wife was Elizabeth Wright, with whom he had five children: Isaiah (b.1689), John (1691–1771), Gideon (1694–1729), Mary (1696–1781), and Elizabeth (b.1698).[47] Isaiah's wife Elizabeth died shortly after the birth of her youngest. Isaiah married Abigail Smith in 1700 and they had five children:[i] Daniel (1701–1770), Thomas (1704–1785), Jeremiah (1707–1777), Abigail (1710–1780), and Samuel (1712–1790). The family lived at Oyster Bay for 14 years, then moved to Smithtown, New York near the Nissequogue River on Long Island, and remained for 19 years. They moved to Sussex County, Delaware in 1721, where Isaiah acquired the Maiden Plantation near the town of Lewes, and daughter Abigail married Alexander Herring (1708–1780).[48]

The Harrison family moved to the Valley of Virginia in 1737 via Alexandria, and camped in the Luray area while waiting for their land grants to be finalized. Isaiah died in 1738 and was buried on the banks of the Shenandoah River. Son John settled at Great Spring, and Samuel settled at nearby Linville. Elvis Presley, through his father Vernon, descended from John and wife Phoebe's daughter Elizabeth and her husband Tunis Hood.[49][50] Isaiah's son Daniel made the family's first Virginia land acquisition in 1739 in Rockingham County, and he and brother Thomas founded the towns of Dayton and Harrisonburg respectively.[43] Daniel used the "Durham arms" as his seal for the legal documents in Rockingham.[51]

Abigail Harrison and her husband Alexander Herring settled at Linville also. Their daughter Bathsheba (1742–1836) married Captain Abraham Lincoln (1744–1786), also of Linville, and they had a son Thomas (1778–1851) who married Nancy Hanks (1783–1818).[52][53] They gave birth to Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) who became president in 1860.[52][53] In his brief autobiography, Lincoln had his own take on his Virginia family roots: "My parents were both born in Virginia of undistinguished families... [m]y paternal grandfather, Abraham Lincoln, emigrated from Rockingham County, Virginia...."[54]

During his final years as a prairie lawyer Lincoln's reputation was elevated in the lead-up to his presidential campaign by his success in a sensational murder trial involving a Harrison relative.[55] Lincoln in 1859 represented his third cousin Simeon Quinn "Peachy" Harrison.[j] Peachy was as well the grandson of a political rival, Rev. Peter Cartwright.[57] Harrison was charged with the murder of Greek Crafton, whom he mortally wounded with a knife after suffering repeated assaults by Crafton. As Crafton lay dying of his wounds, he confessed to Cartwright that he was responsible for provoking Harrison. Lincoln called Cartwright to testify as to the confession but the judge initially denied its use as inadmissible hearsay. Lincoln succeeded in obtaining an acquittal after arguing with the judge, to the point of risking contempt, but ultimately convincing him to admit the testimony and confession as a dying declaration.[55]

Local educators, physicians, and authors

[edit]

Daniel Harrison served as a captain in the French and Indian War and later as a deputy sheriff in Augusta County. Brother Thomas was a lieutenant in that conflict. Daniel's son "Col. Benjamin" (1741–1819) was a regimental commander in the Virginia Militia during the revolution, and then was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates.[58] Among their descendants were physicians and educators, including Benjamin's son, Peachy Harrison (1777–1848), the great-uncle and namesake of Lincoln's aforementioned client; in addition to his medical practice he was county sheriff and served as well at the House of Delegates, the Virginia Senate, and the state's Constitutional Convention.[59]

The latter's son, Dr. Gessner Harrison (1807–1862), graduated with an M.D. and LL.D. from the University of Virginia, and in 1828 was appointed by the school's rector, James Madison, as a professor. He was highly regarded in the classics and linguistics, and served as faculty chairman. The devout Gessner is also remembered for declining Thomas Jefferson's invitation to Sunday dinner at Monticello, saying it would represent a desecration of the sabbath, and a betrayal of his equally devout father. Jefferson promptly commended him for his "filial piety" and arranged it for another evening. Gessner's family became a fixture in Jefferson's "Academical village."[60]

Gessner married Prof. George Tucker's daughter Eliza, and their daughter Mary Stuart (1834–1917) married Prof. Francis Smith. She became an author and translator at the university; her Virginia Cookery Book (1885) was one of the nation’s first modern day cookbooks.[61] She also played a pivotal role in the establishment of a church on the University of Virginia campus. She was among the country's early advocates for women's rights, speaking on behalf of Virginia women in Chicago at the 1893 World's Congress of Women.[61][k] At the request of the Virginia governor, in 1895 she represented the commonwealth's female workers at the Board of Women's convention at the International Exposition in Atlanta.[61]

Mary Stuart's daughter, Rosalie Smith (1870–1956), married an aforementioned descendant of the James River family, Dr. Isaac Carrington Harrison; Dr. Harrison again was a descendant of Edmund Harrison of the Oaks, and a son of Rev. J. Hartwell Harrison. Isaac Carrington was the first of three by that name to take an M.D. at the university.[63] His son Hartwell Harrison (1909–1984) became a professor of surgery at Harvard University, and chief of the Urology Dept. at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, MA. He was a member of the surgical team which in 1954 brought kidney transplantation to the world; he removed the donor's kidney, and then assisted with the recipient's operation. He became a co-author of the textbook Urology.[64]

Other Harrisons in Virginia

[edit]A Prince William County line was founded by Burr Harrison (1637–1697) originally of Westminster, England. This line includes Virginia House delegates, U.S. congressmen, and a judge. Among them are Burr Harrison (1734-1790) and his namesake.

Another York County line begins with Richard Harrison (1600–1664) from Essex, England.[65]

Slavery involvement

[edit]Both of the Virginia Harrison families owned and traded slaves, whose treatment at their hands was exploitive, and characteristic of the institution.

Biographer Clifford Dowdey states "...among the worst aspects is the presumption that the men in the Harrison family, most likely the younger, unmarried ones, and the overseers, made night trips to the slaves' quarters for carnal purposes."[66][l] Though it is known that Benjamin Harrison V owned mullatoes, no record has been revealed as to parentage.[68] As with all planters, the Harrisons were able to provide for the slaves' sustenance on their plantations. But Dowdey further portrays the Harrisons' incongruity, saying the slaves "...were respected as families, and there developed a sense of duty about indoctrinating them in Christianity, though there was a diversity of opinion about baptizing children who were property."[66]

Dowdey adds that, "[I]n all divisions of slaves, Benjamin IV specifically forbade the splitting up of slave families."[66] This was eventually compromised by the ever-widening distribution of estates, as primogeniture waned. Benjamin Harrison V in 1772 joined a Virginia House of Burgesses committee, including Thomas Jefferson, which submitted a petition to King George, requesting that he abolish the slave trade. The King, however, rejected it.[69]

The Harrison families eventually abandoned their slaveholding as the abolitionist movement began to take hold with the civil war.[66] Future President Benjamin Harrison had already begun his political career in Indiana and joined the fledgling Republican party in 1856, then being built in opposition to slavery.[70] Abraham Lincoln similarly joined that party, and made effective efforts to end slavery by his Emancipation Proclamation, the victory of his Union army in the Civil War, and his promotion of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[71]

Legacies

[edit]

Benjamin IV's Berkeley Plantation is the most widely known homestead of the Harrison family in Virginia. Other historic Virginia homes of the family include Brandon Plantation, Upper Brandon, Hunting Quarter, The Oaks in Amelia, VA, The Wigwam, Four Mile Tree, and Kittiewan.[72]

The Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge is a drawbridge across the James River, named in honor of "the Signer". Fort Benjamin Harrison near Indianapolis, Indiana was named for President Benjamin Harrison, who was born in Ohio.[72] The Shenandoah Harrisons also lent their names to Harrison Hall at James Madison University, Daniel Harrison House in Dayton, and memorials at the University of Virginia.[73]

Fort Harrison outside of Richmond, Virginia was an important component of the Confederate defenses of Richmond during the American Civil War. It was named after Lieutenant William E. Harrison (1832–1873), a Confederate engineer and descendant of Burr Harrison.[74]

Other family politicians and public servants

[edit]- Carter Henry Harrison I (1736–1793), son of Benjamin Harrison IV, Virginia House delegate

- Carter Bassett Harrison (1752–1808), son of Benjamin Harrison V, member of the Virginia General Assembly (1784–1786; 1805–1808), U.S. House of Representatives (1793–1799)

- Burwell Bassett (1764–1841), first cousin of William Henry Harrison, Virginia House delegate (1787–89 and 1819–21), Virginia state senator (1794–1805), Representative from Virginia (1805–13, 1815–1819, and 1821–1829)

- Russell Benjamin Harrison (1854–1936), son of President Benjamin Harrison, Indiana Representative (1921–1925), Indiana State Senator (1925–1933).

- Carter Harrison Sr. (1825–1893), son of Carter H. Harrison II, Mayor of Chicago (1879–1887)

- Carter Harrison Jr. (1860–1953), Mayor of Chicago (1897–1905; 1911–1915)

- Randolph Harrison McKim (1842–1920), descendant of Carter Henry Harrison I, Episcopal Minister, Confederate Chaplain and author whose work is memorialized on the Confederate Memorial relocated at New Market Battlefield Park.

- Henry Benjamin "Happy" Harrison (1888–1967), postmaster of La Porte, Texas (1930), Mayor of La Porte, Texas (1934–1936).

- William Henry Harrison III (1896–1990), son of Russell Benjamin Harrison, Wyoming State Representative (1945–1950), Representative from Wyoming (1951–1955, 1961–1965, and 1967–1969)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Harrisons are among four families to have two presidents with the same surname; the others are the Adams, Roosevelt, and Bush families. While presidents Andrew Johnson and Lyndon B. Johnson share a surname, no familial connection is known.

- ^ National obituaries of Albertis Harrison reference this family connection, though an unsourced claim says he personally refuted it.[1][2]

- ^ Historian Francis Burton Harrison denies the relationship between Thomas and Benjamin, but supporting evidence is lacking.[13]

- ^ Virginia historian and biographer Clifford Dowdey states that none of the successive Benjamins used the numerical suffix; it is employed by historians as a convenient tool for distinguishing them.

- ^ The Harrison homestead is also the site where, on December 4, 1619, there occurred one of the first recognized observances of a day of thanksgiving. It is also the location where in 1862 the Army bugle call of "Taps" was written and first played.[23][24]

- ^ After George Washington was named to lead the army, Adams complained there was an attempt by the Harrison-Hancock faction to undermine him and Lee in the eyes of the new commander.[7]

- ^ In 1788 Benjamin V joined Patrick Henry, George Mason, and John Tyler in opposing ratification of the Federal Constitution, and was thereby irreparably estranged from Washington.[7]

- ^ Though Thomas' last will and testament of 1682 makes no mention of Isaiah, it omits as well his eldest son Thomas, born in Chester in 1661.[13]

- ^ J. Houston Harrison's reference to Abigail's maiden name of Smith indicates an uncertainty but no detail is offered.

- ^ Peachy also descended from Isaiah Harrison, through Isaiah's son Daniel.[56]

- ^ The Women's Congress was part of the Chicago World's Fair, the closing ceremonies of which were cancelled due to the assassination of five-term mayor Carter Harrison, Sr. of the James River family.[62]

- ^ Dowdey's award-winning work concentrated on colonial and Civil War history.[67]

References

[edit]- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (1995-01-25). "Albertis S. Harrison Jr., 88, Dies; Led Virginia as Segregation Fell". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- ^ "Albertis S. Harrison Dies at 88". The Washington Post. January 25, 1995. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, p. 79.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 80–83.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smith 1978.

- ^ Harrison, Francis Burton. “Commentaries upon the Ancestry of Benjamin Harrison: VI. Benjamin Harrison of Gobions Manor.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 54, no. 4, 1946, pp. 327–38. JSTOR website Retrieved 4 Oct. 2023.

- ^ Harrison, Francis Burton. “Harrisons in Virginia during the Reign of James I (Concluded).” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 51, no. 4, 1943, p. 327 fn 8. JSTOR website Retrieved 1 Oct. 2023.

- ^ Harrison, Francis Burton. “Commentaries upon the Ancestry of Benjamin Harrison: V. Benjamin Harrison of Aldham and Stationer Harrisons.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 54, no. 3, 1946, pp. 244–54. JSTOR website Retrieved 30 Sept. 2023.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Keith 1893, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f Harrison, Francis Burton 1945.

- ^ McConathy 1972.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Harrison, Francis Burton 1946.

- ^ a b "Thomas Harrison". University of Cambridge. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, p. 91.

- ^ Dowdey 1957, p. 52.

- ^ Dowdey 1957, p. 98.

- ^ Dowdey 1957, p. 103-115.

- ^ Dowdey 1957, p. 146.

- ^ Dowdey 1957, pp. 29–37.

- ^ "John F. Kennedy XXXV President, Thanksgiving Proclamation, Nov. 5, 1963". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ^ Dowdey 1957, pp. 157–58.

- ^ "Benjamin Rush to John Adams, July 20, 1811". NPS. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ Dowdey 1957, pp. 263–264.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Virginia". Library of Virginia. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ "Edmund Harrison to Thomas Jefferson, December 30, 1802". National Archives. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ "The Oaks". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Dowdey 1957, pp. 291–315.

- ^ Gugin & St. Clair, p. 18.

- ^ Bruce 1895, p. 229.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 7–8.

- ^ New York Times, "Albertis S. Harrison Jr., 88, Dies; Led Virginia as Segregation Fell", January 25, 1995

- ^ "Albertis S. Harrison Dies at 88". The Washington Post. January 25, 1995. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ^ "Albertis S. Harrison, 88". Baltimore Sun. 25 January 1995. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Hooker 1998.

- ^ Lindenau 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Williamson 1927.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, p. 88.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 101–105.

- ^ a b c Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 10–15.

- ^ a b Harrison, J. Houston, p. 99.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 89–93.

- ^ Hood 1960, p. 449.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, p. 123.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 42–55, 123.

- ^ Hood 1960, pp. 93–105.

- ^ Guralnick & Jorgensen 1999, p. 3.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, p. 128.

- ^ a b Wayland 1987, pp. 24–57.

- ^ a b Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 280–286, 350–351.

- ^ Lincoln 1859.

- ^ a b Dekle 2015.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, p. 480.

- ^ "The Grisly Murder Trial That Raised Lincoln's Profile". History Channel. April 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 200, 204, 296.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, p. 396.

- ^ "Gessner Harrison". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved Feb 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c Willard 1893.

- ^ Larson 2003.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, p. 156.

- ^ Murray, Joseph E. (1990). "Nobel Lecture: The First Successful Organ Transplants in Man". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 287–289.

- ^ a b c d Dowdey 1957, p. 164.

- ^ "Coski, Ruth Ann, "Clifford Shirley Dowdey (1904–1979), Dictionary of Virginia Biography". Library of Virginia. 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "To Geo. Washington from Benj. Harrison,Sr., March 31, 1783". National Archives. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ Smith 1978, p. 22.

- ^ Moore & Hale, 2006, p. 29

- ^ "Abraham Lincoln". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Dowdey 1957, pp. 270–315.

- ^ Harrison, J. Houston, pp. 478–556.

- ^ Hannings 2006, p. 566.

Works cited

[edit]- Bruce, Philip A. (January 1895). The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 2. Virginia Historical Society.

- Calhoun, Charles William (2005). Benjamin Harrison. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-6952-5.

- Dekle, George R. (20 November 2015). "Abraham Lincoln's Last Murder Case:News Reports". Illinois State Register & Illinois State Journal. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- Dowdey, Clifford (1957). The Great Plantation. Rinehart & Co.

- Gugin, Linda C.; St. Clair, James E., eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press and the Indiana Historical Bureau. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.

- Guralnick, Peter; Jorgensen, Ernst (1999). Elvis Day by Day: The Definitive Record of His Life and Music. Ballantine.

- Hannings, Bud (2006). Forts of the United States: An Historical Dictionary, 16th through 19th Centuries. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1796-4.

- Harrison, Francis Burton (October 1945). "The Reverend Thomas Harrison, Berkeley's "Chaplain"". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 53 (4). Virginia Historical Society: 302–311. JSTOR 4245373. [Kinship is noted.]

- Harrison, Francis Burton (October 1946). "Benjamin Harrison of Gobions Manor". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 54 (4). Virginia Historical Society: 327–338. JSTOR 4245437. [Kinship is noted.]

- Harrison, J. Houston (1935). Settlers by the Long Grey Trail. Joseph K. Ruebush Co.. [The author's kinship is noted; an extensive bibliography (pp. 619–627) is also noted, as well as a heavy reliance upon public records.]

- Hood, Dellman O. (1960). The Tunis Hood Family: Its Lineage and Traditions. Metropolitan Press.

- Hooker, Mary Harrison (1998). All Our Yesterdays. Boca Grand.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) [Kinship is noted.] - Keith, Charles P. (1893). Ancestry of President Benjamin Harrison. Lippincott Co.

- Larson, Erik (2003). The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America. New York: Vintage Books a Division of Random House, Inc.

- Lincoln, Abraham (December 20, 1859). "Short Autobiography". The History Place. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Lindenau, Val-Rae (September 14, 2021). "Sarah E. Harrison House". Old West End. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- McConathy, Ruth H. (1972). Supplement to the House of Cravens. University of Wisconsin.

- Smith, Howard W. (1978). Edward M. Riley (ed.). Benjamin Harrison and the American Revolution. Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission.

- Moore, Anne Chieko; Hale, Hester Anne (2006). Benjamin Harrison: Centennial President. Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-6002-1066-2.

- Smith, Mary Stuart (1893). Eagle, Mary K. O. (ed.). The Congress of Women: The Virginia Woman Today. Philadelphia: S. I. Bell. pp. 410–411.

- Wayland, John W. (1987). The Lincolns in Virginia. Harrisonburg: C.J. Carrier.

- Willard, Frances Elizabeth (1893). A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life (Public domain ed.). Moulton. p. 669. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- Williamson, Harold (February 1927). "Sarah Harrison Has Taken 4000 Traveling Men to Church". The American Magazine.