Oology

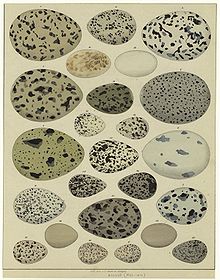

Oology (/oʊˈɒlədʒi/;[1] also oölogy) is a branch of ornithology studying bird eggs, nests and breeding behaviour. The word is derived from the Greek oion, meaning egg. Oology can also refer to the hobby of collecting wild birds' eggs, sometimes called egg collecting, birdnesting or egging, which is now illegal in many jurisdictions.[2]

History

[edit]As a science

[edit]

Oology became increasingly popular in Britain and the United States during the 1800s. Observing birds from afar was difficult because high-quality binoculars were not readily available.[2] Thus it was often more practical to shoot the birds or collect their eggs. While the collection of the eggs of wild birds by amateurs was considered a respectable scientific pursuit in the 19th century and early 20th century,[3] from the mid 20th century onwards it was increasingly regarded as being a hobby rather than a scientific discipline.

In the 1960s, the naturalist Derek Ratcliffe compared peregrine falcon eggs from historical collections with more recent egg-shell samples, and was able to demonstrate a decline in shell thickness.[4] This was found to cause the link between the use by farmers of pesticides such as DDT and dieldrin, and the decline of British populations of birds of prey.

As a hobby

[edit]Egg collecting was still popular in the early 20th century, even as its scientific value became less prominent. Egg collectors built large collections and traded with one another. Frequently, collectors would go to extreme lengths to obtain eggs of rare birds. For example, Charles Bendire was willing to have his teeth broken to remove a rare egg that became stuck in his mouth. He had placed the egg in his mouth while climbing down a tree.[2]

In 1922, the British Oological Association was founded by Baron Rothschild, a prominent naturalist, and the Reverend Francis Jourdain; the group was renamed the Jourdain Society after Jourdain's death in 1940. Rothschild and Jourdain founded it as a breakaway group after egg collecting by members of the British Ornithologists' Union was denounced by Earl Buxton at a meeting of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.[5]

Poaching laws

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United Kingdom and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2015) |

In the UK

[edit]Legislation, such as the Protection of Birds Act 1954 and Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 in the United Kingdom, has made it impossible to collect wild birds' eggs legally. In the United Kingdom, it is only legal to possess a wild-bird's egg if it was taken before 1954, or with a permit for scientific research; selling wild birds' eggs, regardless of their age, is illegal.[6]

However, the practice of egg collecting, or egging, continues as an underground or illegal activity in the UK and elsewhere.[4][7] In the 1980s and 1990s, the fines allowed by the law were only a moderate deterrent to some egg collectors.[4] However, the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 allowed for six months' imprisonment for the possession of the eggs of wild birds[6] and, since it came into force, a number of individuals have been imprisoned, both for possessing and for attempting to buy egg collections.[4] The Jourdain Society continued to meet although membership dwindled after 1994, when a dinner of the society was raided by police, assisted by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). This resulted in six members being convicted and fined.[5]

Despite this, some of those who engage in egg collecting show considerable recidivism in their activity. One, Colin Watson, was convicted six times before he fell to his death in 2006, while attempting to climb to a nest high up in a tree.[8] While the threat of imprisonment after 2000 encouraged some to give up egg collecting,[4] others were not deterred. One individual has been convicted ten times[9] and imprisoned twice.[10] As recently as 2018, a man was imprisoned for amassing a collection of 5000 eggs,[11] after previously being imprisoned in 2005.[12] Another man was convicted of possessing 200 eggs in 2021.[13]

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds has been particularly active in fighting illegal egg collection and maintains an investigative unit that collects intelligence on egg collectors and assists police in mounting prosecutions on them, in addition to investigating other wildlife crimes.[5] At one point, RSPB staff were being trained by soldiers from the Brigade of Gurkhas in camouflage skills and in surveillance, map and radio techniques, to better enable them to guard nests of rare birds.[14]

In the United Kingdom, to avoid the possibility of prosecution, owners of old egg collections must retain sufficient proof to show, on the balance of probabilities, that the eggs pre-date 1981. However owners of genuinely old collections are unlikely to face prosecution as experienced investigators and prosecutors are able to distinguish them from recently collected eggs.[15] It is illegal to sell a collection, regardless of the eggs' age, so old collections may only be disposed of by giving the eggs away or by destroying them. Museums are reluctant to accept donations of collections without reliable collection data (i.e. date and place that they were collected) that gives them scientific value. Also, museums no longer put egg collections on public display.[16]

In the US

[edit]In the United States, the collection and possession of wild bird eggs is also restricted, and in some cases is a criminal act. Depending on the species, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act,[17] the Lacey Act,[18] the Endangered Species Act,[19] or other laws may apply.

Collecting

[edit]Methods

[edit]When collecting eggs, normally the whole clutch of eggs is taken. Because eggs will rot if the contents are left inside, they must be "blown" to remove the contents. Although collectors will take eggs at all stages of incubation, freshly laid eggs are much easier to blow, usually through a small, inconspicuous hole drilled with a specialized drill through the side of the eggshell. Egg blowing is also done with domestic bird's eggs for the hobby of egg decorating.

Major research collections

[edit]- Natural History Museum (610,000 eggs), UK

- Delaware Museum of Natural History (520,000 eggs), US

- H. L. White Collection, Melbourne, Australia

- National Museum of Natural History (190,000 eggs), Washington DC, US

- Muséum de Toulouse (150,000 eggs), Toulouse France

- San Bernardino County Museum (41,000 clutches with 135,000 eggs)[2][20]

- Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology (190,000 clutches with >800,000 eggs), California, US

- Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History (formerly the Museum of Comparative Oology) (11,000 egg sets from 1,300 species), Santa Barbara, California, US

Oologists and egg collectors

[edit]- Charles Bendire

- Archibald James Campbell, author of Nests and Eggs of Australian Birds, Including the Geographical Distribution of the Species and Popular Observations Thereon (Sheffield England, Pawson & Brailsford, 1900) Reissued 1974, by Wren, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

- E. J. Court of Washington, DC[21]

- Charles Johnson Maynard, author of Eggs of North American Birds (Boston: DeWolfe, Fiske & Co., 1890)

- Francis Charles Robert Jourdain

- Colin Watson

Oology related publications

[edit]Numerous books, and at one point a journal, have been published on egg collecting and identification:[2]

- Thomas Mayo Brewer, (1814–80), an American ornithologist, wrote most of the biographical sketches in the History of North American Birds, by Baird, Brewer, and Ridgway (1874–84). He has been called "the father of American oölogy". He wrote North American Oölogy which was partially published in 1857.

- William Chapman Hewitson, Illustrations of Eggs of British Birds, (third edition, London, 1856).

- Archibald James Campbell, Nests and Eggs of Australian Birds: Embracing Papers On "Oology of Australian Birds," Read Before the Field Naturalists' Club of Victoria, Supplemented by Other Notes & Memoranda; Also, an Appendix of Several Outs - Nesting, Shooting Etc., (A. J. Campbell, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 1883) (Cover title: Oology of Australian Birds. Ferguson no. 7870)

- Oliver Davie, Nests and Eggs of North American Birds, (fifth edition, Columbus, 1898).

- Alfred Newton, Dictionary of Birds, (New York, 1893–96).

- Gentry, Thomas (1882). Nests and Eggs of Birds of the United States. Philadelphia.

In popular culture

[edit]- Chapter 7 of P.G. Wodehouse's novel The Pothunters describes a student's interest in hunting for the eggs of a water wagtail.

- A 2007 episode of Midsomer Murders "Birds of Prey" surrounds illegal oology.

- In 2017, Artist Andy Holden and father, ornithologist Peter Holden, staged a series of exhibitions titled Natural Selection, staged by Artangel,[22] which took place at Bristol Museum, Towner Gallery in Eastbourne, and Leeds Art Gallery, in which they explored the 'social history' of oology in Britain. The exhibition included a vast recreation of an illegal egg collection, as well as a film narrating the history of egg collecting in Britain.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Oology Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster". merriam-webster.com. [Merriam-Webster]. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Henderson, Carrol L (2007). Oology and Ralph's Talking Eggs. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 200. ISBN 978-0-292-71451-9.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 978.

- ^ a b c d e Barkham, Patrick (11 December 2006). "The egg snatchers". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ a b c Rubinstein, Julian (22 July 2013). "Operation Easter The hunt for illegal egg collectors". The New Yorker. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Egg Collecting". Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ George, Rose (3 June 2003). "Egg poachers at large". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Wainright, Martin (27 May 2006). "The day Britain's most notorious egg collector climbed his last tree". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Dimmer, Sam (2014-03-05). "No bird for Longford egg collector after court date". Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ George, Sally (3 January 2008). "Compulsion of prolific egg thief". BBC News. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Walsh, Peter (2018-11-27). "Man jailed and told to give his collection of 5,000 rare bird eggs to Natural History Museum". Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ "Norfolk man who illegally hoarded 5,000 rare eggs jailed". BBC News. 2018-11-27. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ "Wild birds' eggs theft: Huddersfield man sentenced". BBC News. 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ Brown, Paul (29 May 2002). "Soldiers train RSPB staff to combat egg thieves". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ "Old egg collections". Advice. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. 12 July 2004. Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Disposing of old egg collections". Advice. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. 30 January 2004. Archived from the original on 2016-03-16. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ "Lacey Act". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ John, Dingell (18 September 1973). "H.R.37 - 93rd Congress (1973-1974): Endangered Species Conservation Act". www.congress.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ "The Hatching of Oology at the County Museum". San Bernardino County Museum.

- ^ William Leon Dawson (March–April 1916). "The New Museum of Comparative Oology". The Condor. 18 (2). Cooper Ornithological Society: 68–74. doi:10.2307/1362747. JSTOR 1362747.

- ^ "Natural Selection". www.artangel.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- ^ Cumming, Laura (2017-09-10). "Andy Holden & Peter Holden: Natural Selection review – artfulness is egg-shaped". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

External links

[edit] Media related to Oology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Oology at Wikimedia Commons- Alberto Masi Egg Gallery

- Poached, a 2015 film documentary about illegal egg collecting

- The Oologist journal

- Morris, Francis Orpen (1853). A Natural History of the Nests and Eggs of British Birds.