Kid Icarus: Uprising

| Kid Icarus: Uprising | |

|---|---|

Box art | |

| Developer(s) |

|

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Masahiro Sakurai |

| Producer(s) | Yoshihiro Matsushima |

| Writer(s) | Masahiro Sakurai |

| Composer(s) | |

| Series | Kid Icarus |

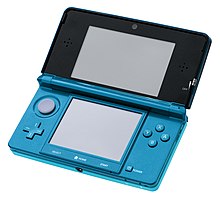

| Platform(s) | Nintendo 3DS |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Third-person shooter, rail shooter |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

Kid Icarus: Uprising[b] is a third-person shooter video game developed by Project Sora and published by Nintendo for the Nintendo 3DS. Released worldwide in March 2012, it is the third installment in the Kid Icarus franchise, the first to be released since Kid Icarus: Of Myths and Monsters in 1991, and the first worldwide release since the original NES game in 1986. It is also the only video game Project Sora made before shutting down in mid-2012.

Kid Icarus: Uprising takes place in a setting based loosely around Greek mythology. The main protagonist is the angel Pit, servant to the Goddess of Light, Palutena. When the Goddess of Darkness Medusa returns to destroy humanity, Pit goes on missions first against her, then against the forces of Hades, the Lord of the Underworld and the source behind Medusa's return. During gameplay, the player controls Pit during airborne rail shooter segments and ground-based third-person shooter segments. In addition to the single-player campaign, various collectable and unlockable items can be obtained, and several multiplayer modes are available for up to six players.

Masahiro Sakurai created Uprising after receiving a request from Satoru Iwata to create a launch title for the then in-development Nintendo 3DS. Development began in 2009, but faced multiple difficulties, such as lack of access to the hardware in its early stages, balancing its many elements, and issues with its control scheme. Sakurai was responsible for writing the story, which retained the lighthearted tone of the first Kid Icarus game while having uninterrupted gameplay. A team of composers worked on the music, including Motoi Sakuraba, Yuzo Koshiro, and Yasunori Mitsuda.

Since release, Uprising has sold over a million copies worldwide and received mainly positive reviews; praise was given to the story, characters, dialogue, graphics, music, and gameplay, although the control scheme was frequently criticized. Elements from the game are prominently featured in the Super Smash Bros. series from its fourth installment onwards.

Gameplay

[edit]Kid Icarus: Uprising is a third-person shooter where players control of the angel Pit during his missions for Palutena, the Goddess of Light. Gameplay is divided into aerial-based rail shooter segments and ground-based segments that feature both linear paths and free-roaming areas. The game's difficulty, or Intensity, is determined by betting hearts in the Fiend's Cauldron before beginning each mission. The difficulty ranges from the very easy "0.0" to the highly difficult "9.0". Pit's combat abilities are divided between long-range attacks using gun-like weapons, and close-quarters melee attacks. During missions, defeating enemies grants the player hearts, the game's currency, which is used to increase difficulty by laying bets against the player's own performance.[1][2] As the game progresses, Pit gains access to weapons separated into nine types, each with unique advantages and disadvantages: bows, bracer-like claws, blades (a combination of a sword and a gun), clubs, orbitars (twin orbs hovering near Pit), staffs, arms (a weapon that fits around his wrist), palms (magical tattoos covering Pit's arm), and cannons. Once equipped, weapons can be tested in the game's Practice Range.[1][3] Using the 3DS' StreetPass network, players can share weapons with other players in the form of Weapon Gems.[4] Other players can pay hearts to convert the gem into a weapon.[1][4] Hearts can be spent to upgrade weapons or fuse Weapon Gems, and gained by dismantling unwanted weapons or converting Weapon Gems.[1]

Each chapter begins with an aerial battle, consisting of an on-rails shooter segment, with Pit being guided along a predetermined path. During these stages, the player moves Pit with the Circle Pad, aims with either the 3DS' stylus or face buttons, and fires with the L button. Not firing for a time allows the player to fire a powerful Charge Shot, which kills several enemies at once. Once on the ground, players control Pit as he traverses through the level, which features more open spaces and hidden areas unlocked when playing on certain difficulties. Pit can either shoot enemies from a distance or attack them up close with melee attacks, while also performing various moves to dodge enemy attacks. The main controls are carried over from aerial segments, but their assigned actions alter slightly. When an enemy strikes Pit, his health bar is depleted, and can be replenished with items scattered throughout levels. If sufficiently damaged, the health bar vanishes and Crisis Mode is activated: this will either end naturally or ended by fully replenishing health with a "Drink of the Gods" item. During Crisis Mode, healing items don't take effect until it ends and Pit will die if he gets hit again, but he can withstand at least one hit before entering Crisis Mode. If Pit is defeated, the player is given the option to continue, but some Hearts are lost from the Fiend's Cauldron and the difficulty is lowered. Completing a level without dying grants additional rewards. In ground-based levels, Pit can take control of various vehicles for short stretches, gaining special attacks unique to each vehicle type. Each stage ends in a ground-based boss battle. Pit has the ability to sprint during ground-based gameplay, but sprinting for too long uses up his stamina and leaves him vulnerable to attack.[1][2]

Uprising supports both local and online multiplayer. Along with the game's single-player story mode, the game also features multiplayer for up to six players locally or via Wi-Fi. Players can compete in team-based cooperative matches or free-for-all melees using standard fighter characters. In the team-based mode, named Light vs. Dark, each team has a health meter that depletes when a player is defeated. The value of the player's weapon determines how far the meter depletes after death, and the player whose death depletes the meter completely will become their team's angel, a more powerful character who represents the team. The match ends when the other team's angel is defeated.[4] In addition to normal ways of playing, Uprising comes bundled with a 3DS stand for the platform for ease of play.[2] Augmented Reality (AR) Cards are collectible and can be used as part of a card contest. Using the 3DS' outer camera, the AR Cards produce "Idols" (representations of characters from Uprising): by lining up the back edges of two AR Cards and selecting the "Fight" option, Idols appear from the cards and battle each other, with the winner being determined by its statistics.[1][5]

Synopsis

[edit]Kid Icarus: Uprising takes place in a world loosely based on Greek mythology, and is set twenty-five years after the events of the first game. Pit, an angel serving the Goddess of Light Palutena, is sent on missions against the Goddess of Darkness Medusa, who threatens to destroy humanity. During his missions, Pit fights Medusa's servant Twinbellows, defeats her commander Dark Lord Gaol with the help of a human mercenary named Magnus, then confronts the Goddess of Calamity Pandora so as to destroy the Mirror of Truth. In the process, the Mirror spawns a doppelgänger called Dark Pit, who absorbs the defeated Pandora's powers and departs. With help from the God of Oceans Poseidon, Pit defeats Medusas's final commander Thanatos. He then retrieves powerful weapons known as the Three Sacred Treasures and uses them to defeat Medusa. When defeated, it is revealed that Medusa was merely a resurrected puppet ruler hiding the true antagonist: Hades, Lord of the Underworld. Hades, by spreading a rumor about a "wish seed" guarded by the Phoenix, provokes war among humanity so as to claim their souls. This war prompts the Nature Goddess Viridi to attack them and Hades' army. Pit and Palutena work against both Viridi and Hades, during the course of which a military base called the Lunar Sanctum is destroyed, releasing an unknown creature.

The deities' ongoing battles prompt an alien race called the Aurum to invade Earth for its resources. The warring deities unite against the threat, and the Sun God Pyrrhon sacrifices himself to banish the Aurum to the far side of the galaxy. Events then move forward three years, when Pit is trapped inside a ring with no clear memory of what happened. Using hosts to make his way to a ruined city, he meets up with Magnus, who reveals that Palutena's army has turned against humanity and that Pit's body is attacking humans. Using Magnus' body, Pit defeats his body and repossesses it. Viridi then flies him to Palutena's capital of Skyworld, which has been reduced to ruins. Viridi reveals that the Lunar Sanctum was a prison holding the Chaos Kin, a soul-devouring creature that escaped when Pit destroyed the base. The Chaos Kin has possessed Palutena and caused her to become deranged. After obtaining the Lightning Chariot, Pit breaks through the defensive barrier around Skyworld's capital and defeats Palutena. The Chaos Kin then steals her soul, and both Pit and Dark Pit follow the Chaos Kin into its dimension to retrieve it. To save Dark Pit from a final attack by the defeated Chaos Kin, Pit overuses his flight powers, burning his wings and nearly killing himself.

Dark Pit takes Pit to the Rewind Spring so time can be reversed for Pit's body. Upon arrival, Pandora's essence escapes from Dark Pit and uses the Spring to restore her body before being defeated by Dark Pit. Pit is restored by the Spring, while the loss of Pandora's powers leaves Dark Pit unable to fly on his own. Now restored, Pit attempts to destroy Hades with the Three Sacred Treasures, but Hades easily destroys them and attempts to eat Pit. After escaping from Hades' insides, Pit is guided by Palutena to the home of the Forge God Dyntos, who fashions a new Great Sacred Treasure after Pit proves himself in multiple trials. Launching a fresh assault, Pit succeeds in injuring Hades, but the Great Sacred Treasure is badly damaged, leaving only its cannon intact. Hades attempts to launch a final attack, but a revived Medusa injures him further before being killed by Hades for defying him. This enables Palutena to supercharge the cannon, and Pit uses it to destroy Hades' body, saving the world. In a post-credits scene, the disembodied Hades states he will likely return in another twenty-five years.

Development

[edit]After completing work on Super Smash Bros. Brawl for the Wii, Masahiro Sakurai was taken out for a meal by Nintendo's then-president Satoru Iwata in July 2008. During their meal, Iwata asked Sakurai to develop a launch title for the Nintendo 3DS. The platform was still in early development at the time, with Sakurai being the first person outside of the company to learn of its existence. On his way home, Sakurai was faced with both ideas and problems: Sora Ltd., which had developed Super Smash Bros. Brawl, had been drastically reduced in size as most of the game's staff had been either from other Nintendo teams or outsourced.[6] While he had the option of creating an easy-to-develop port for the system, Sakurai decided to create a game around the third-person shooter genre, which was unpopular in Japan yet seemed suited to the planned 3D effects of the 3DS. At this point, the project was still an original game. In later conversations with Iwata, Sakurai decided to use an existing Nintendo IP as the game's basis. This was inspired by feedback received from players of Super Smash Bros. Brawl that many members of its character roster had not been in an original game for some time. After a positive response from Iwata at the suggestion, Sakurai ran through the possible franchises. One of the franchises under consideration by Sakurai was Star Fox, but he felt that there were some restrictions in implementing the planned gameplay features within the Star Fox setting.[7] He ultimately decided to use Kid Icarus due to its long absence from the gaming market and continued popularity in the West. He also decided upon him due to his involvement with the character through Super Smash Bros. Brawl. Once he had chosen a possible series, he conceived the basic sequence of five-minute aerial segments, ground-based combat, and bosses at the end of chapters. After submitting his plan, Sakurai was given the go-ahead to develop the game.[8] Uprising was the first Kid Icarus game to be developed since the Western-exclusive 1991 Game Boy title Kid Icarus: Of Myths and Monsters, and the first to be planned for Japan since the original Kid Icarus in 1986.[9][10]

Sakurai took responsibility for writing the game's story and script himself.[11] With video game stories, Sakurai believes that developers lack an ability to balance story-based gameplay hindrances with the prerequisite of victory over enemies. To this end, he was obsessed with striking that balance with Uprising, and so wrote the entire story script himself. He did this so he could write a story that "jibed" with the flow and style of gameplay. The characters' roles and personalities were shaped by their roles in the game and the game structure itself. He also wanted the dialogue to mesh perfectly with the story and music: by writing the script himself, Sakurai was able to sidestep the necessity of explaining to another writer all the time. This also made fine tuning much easier for him.[11] While retaining the first game's Greek mythic influences, the mythology itself had no direct influence on the story of Uprising.[12] Sakurai also wanted to make sure that the game's Greek influence did not stray in the same direction as the God of War series.[13] For the main story, Sakurai avoided portraying a simple good versus evil situation; instead, he had the various factions coming into conflict due to clashing views rather than openly malicious intentions, with their overlapping conflicts creating escalating levels of chaos for players to experience. Rather than relying on standalone cutscenes, the majority of story dialogue was incorporated into gameplay. What cutscenes there were, were made as short as possible. Events after Chapter 6 were deliberately kept secret during the run-up to release so players would be taken by surprise by what they experienced. The character of Palutena, a damsel in distress in the original game, was reworked as Pit's partner and support. The original idea was for Pit to have a mascot character as his support, but was abandoned in favor of Palutena. Pit and Palutena's dialogue was influenced by the traditions of Japanese double acts.[7][13][14][15] Dark Pit was written as a mirror image of Pit rather than an evil twin.[15] A key element was retaining the humorous elements from the first game, such as anachronistic elements and silly enemy designs. This attitude, as observed by Sakurai, contrasted sharply with the weighty or grim character stories present in the greater majority of video games.[13][14] The story was originally three chapters longer than the final version, but these additional parts needed to be cut during early development.[13]

Design

[edit]

In November 2008, after Sakurai was given the go-ahead to develop Uprising, he rented out an office in Takadanobaba, a district of Tokyo. At this stage, due to the game's platform still being in early development, there were no development tools available for Sakurai to use. Between November and March 2009, Sakurai finalized his vision for the game.[8] During this period, to help design the game's settings and characters, Sakurai hired several outside illustrators to work on concept art: Toshio Noguchi, Akifumi Yamamoto and Masaki Hirooka. The art style was inspired by manga.[8][15][16] In January 2009, development studio Project Sora was established for Uprising's development. At its inception, it had a staff of 30. With the start of active recruitment in March, the game officially entered development: at the time, it was the very first game to be in development for the new platform.[8][17] During this early stage, due to the lack of platform specific development tools, the team were developing the game on Wii hardware and personal computers.[14] The changing specifications of the developing hardware resulted in multiple features undergoing major revisions.[15] This hardware instability led to a protracted development cycle: in the event, the team managed to fully utilize the platform's capabilities, doing detailed work on how many enemies they could show on the screen at any one time. Debugging also took a long time due to the size and variability of gameplay built into Uprising.[18]

From the start, Uprising was meant to be distinct from the original Kid Icarus: while Kid Icarus was a platformer featuring horizontal and vertical movement from a side-scrolling perspective, Uprising shifted to being a fully 3D third-person shooter divided between airborne and ground-based segments in each chapter.[9] Much of the game's depth and scale came from Sakurai's own game design philosophy, along with the inclusion of various weapon types that opened up different strategic options.[19] The number of weapons available in-game was decided from an early stage, as Sakurai wanted solid goals for the development team so development would go smoothly.[12] The original Kid Icarus was notorious for its high difficulty, but this was an aspect Sakurai wanted to adjust so that casual gamers could also enjoy Uprising. For this reason, the Fiend's Cauldron was created as a user-controlled means of both setting difficulty and allowing players to challenge themselves by wagering resources against their performances.[14][18] The Fiend's Cauldron tied into the game's overall theme of "challenge".[13] The game's difficulty was one of the three key elements decided upon by Sakurai, alongside the music and lighthearted storyline.[9] The addition of the AR Card game was based on Sakurai's wish to fully utilize the 3DS's planned features, and was inspired by the trophy viewing option from Super Smash Bros. Brawl. Due to the volume of cards produced, the team needed to create a special system based on a colorbit, an ID recognition code along the bottom edge of a card. After consideration, it was decided to have the "Idol" displays able to fight each other, with battles revolving around a stat-based rock paper scissors mechanic. It also provided a means for players to measure the strength of characters without directly connecting their consoles.[14]

While the game featured fast-paced action and a high difficulty, its control scheme was designed to be relatively simple. This was because Sakurai had observed equivalent console games using all the buttons on a console's controller, creating a barrier for first-time players. To open up the game for newcomers while keeping gameplay depth, the team took the three basic controls and combined them with the game's structure.[9] In later interviews, Sakurai said that the team had great difficulty properly incorporating the control scheme into the game. Their initial goal was to fully utilize the 3DS's processing power, which left little room for incorporation of elements such as the Circle Pad Pro, which was created fairly late in the game's own development cycle. Due to the lack of space, providing independent analogue controls for left-handed players was impossible.[13][20] The inclusion of a stand for the system to help players properly experience Uprising as part of the game's package was requested by the team from an early stage.[15] A major element of the 3DS's design that influenced development was the touchscreen, used for aiming Pit's weapons. While similar touch-based aiming had been used for first-person shooters on the Nintendo DS, Sakurai was dissatisfied with the resulting experience, phrasing it as "like trying to steer with oars". With the 3DS's touchscreen, the team was able to create a more responsive experience similar to a computer mouse, creating the system of flicking the 3DS stylus to change camera and character direction. The team also attempted to tackle the ingrained problem of trying to move the character and camera while stereoscopic 3D was enabled.[7][18] The multiplayer functionality was decided upon from an early stage, with the main focus being on balancing it with the single-playing campaign. The design for weapon usage was inspired by fighter choices in Super Smash Bros. Brawl, contrasting with weapon systems from other equivalent Western shooters.[9][19]

Music

[edit]| New Light Mythology: Palutena's Mirror Original Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Motoi Sakuraba, Yuzo Koshiro, Masafumi Takada, Noriyuki Iwadare, Takahiro Nishi, and Yasunori Mitsuda | |

| Released | 21 August 2012 |

| Genre | Video game soundtrack |

| Length | 216:07 |

| Label | Sleigh Bells |

| Producer | Yasunori Mitsuda |

The music was composed by a team consisting of Motoi Sakuraba, Yuzo Koshiro, Masafumi Takada, Noriyuki Iwadare, Yasunori Mitsuda, and Takahiro Nishi. Nishi served as music director, while orchestration was handled by Mitsuda and his studio assistant Natsumi Kameoka. Early in the game's development, Sakurai and Nishi were in discussions about what the style of Uprising's music would be, and which composers to hire for it.[21] The composers were those who had contributed most prominently to Super Smash Bros. Brawl.[15] The music involved both live orchestral music, synthesized tracks, and tracks that combined both musical styles. The air battle themes were created to match the dialogue and action on-screen, which was stated early on to be an important goal. Another aspect of the music, as noted by Koshiro, was that it should stand out while not interfering with dialogue. Sakuraba and Koshiro were brought in fairly early, and thus encountered difficulties with creating their music. Sakuraba recalled that he needed to rewrite the opening theme multiple times after his first demo clashed with the footage he saw due to his not knowing much about the game's world. Takada came on board when there was an ample amount of footage, but was shocked when he saw gameplay from the game's fifth chapter and tried to create suitable music within Sakurai's guidelines.[21]

Iwadare was asked to create memorable melodies, but found creating suitable tracks difficult as many of his initial pieces were thrown out. For Kameoka, recording the live orchestral segments proved a time-consuming and difficult business: each element of a track was recorded separately, then mixed into a single track, then each orchestral element needed to be adjusted for speed and tone so they lined up correctly. According to Mitsuda, the live recording of music spanned seven full sessions, estimated by him as being the largest-scale musical production for a video game to that date. He was entirely dedicated to orchestration and recording for four months. Mitsuda was tasked with creating the music for the game's 2010 reveal trailer, which he knew was an important task as it would have an international audience. He estimated that around 150 people in total worked on the score throughout its creation.[21]

In separate commentary on selected tunes, Sakurai drew to particular tracks. Sakuraba's main theme was made notably different from earlier themes incorporated into the soundtrack, because he wanted Uprising to have an original theme to distinguish it from its predecessors: as it played in the main menu between missions, the team treated it as Palutena's theme tune. Koshiro composed "Magnus's Theme": the theme had two distinct versions based around the same motif, alongside incorporating one of Hirokazu Tanaka's original tracks for Kid Icarus. The theme for Dark Pit was composed by Western gun duels in mind, making heavy use of the acoustic guitar to give it a "Spanish flavor": multiple arrangements were created, including a version for use in multiplayer. Mitsuda was responsible for the "Boss Theme", and worked to make the music positive and encouraging as opposed to the more common "oppressive" boss tunes heard in games. Iwadare's "Space Pirate Theme", written for a faction of the Underworld Army, combined musical elements associated with both seafaring pirates and outer space. Iwadare also composed "Hades' Infernal Theme", which mixed choral, circus and "violent" elements to both symbolize Hades's contrasting attributes and distinguish him from Medusa.[22]

Koshiro's track, "Wrath of the Reset Bomb", used the motif associated with Viridi, which would be reused in multiple tracks. According to Sakurai, it was only intended to be used in one level, but he liked it so much that he made it the theme for Viridi's Forces of Nature. A track that went through multiple redrafts was "Aurum Island", the theme associated with the titular alien invaders: while every attempt made to create a theme ended up as a "techno-pop song", the tune underwent multiple adjustments so it would not clash with the rest of the soundtrack while retaining its form. "Lightning Chariot Base", due to the size of the level, was designed so players would notice its presence without growing tired of it. "Practice Arena", the tune for the pre-multiplayer training area, was designed by Takada to have a light, analogue feel; it was originally composed for a different unspecified area, but it was decided that it fitted well with the build-up to a multiplayer match.[22]

Selected music from the game was originally released in a promotional single CD by Club Nintendo.[23] A limited 3-CD official soundtrack album, New Light Mythology: Palutena's Mirror Original Soundtrack, was released through Mitsuda's record label Sleigh Bells on 21 August 2012.[24][25] The soundtrack received praise; Video Game Music Online writer Julius Acero gave it a perfect 5-star rating, calling it "the best modern Nintendo soundtrack, beating out the likes of The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword and even Super Smash Bros. Brawl". It also won the site's "Best Score award in the Eastern category".[25] Patrick Gann, writing for Original Sound Version, called it an "epic musical score", praising the developers for bringing together the composers to create the score.[26]

Release

[edit]In 2009, Sakurai was working on a new game through Project Sora.[17] Uprising was officially announced at Nintendo's E3 2010 conference immediately following the announcement of the Nintendo 3DS.[27] In an interview closer to release, Sakurai said that he had misgivings about Uprising being shown off at gaming expos since 2010 while it was still in an unfinished state.[12] The game suffered a delay that pushed its release into 2012,[28][29] ultimately released worldwide in March.[30][31][32][33] The game's box art was almost identical between its Japanese and English releases.[34]

The English version of Uprising was handled by Nintendo of America's localization department, Nintendo Treehouse.[35][36] Sakurai gave the localization team "a lot of leeway" for this part of development. Much of the original script's humor stemmed from the usage of Japanese conversational nuances, which would not have been organized properly into English. Because of this, adjustments needed to be made so that it was enjoyable for English speaking audiences.[35] The video game references were taken almost directly from the Japanese dub, with some adjustments so they resonated with the Western market. As with other localizations, the team avoided topical references so the scripts would take on a timeless feel.[36] The casting and recording director was Ginny McSwain.[37] Three prominent English cast members were Antony Del Rio who voiced Pit and Dark Pit, Ali Hillis who voiced Palutena, and Hynden Walch who voiced Viridi. The majority of voice recording was done separately, but half of the dialogue between Pit and Palutena was recorded by the two actors together before scheduling conflicts forced them to record their lines separately, responding to either voice clips of the other actors or the director reading lines.[38] The European version only included the English voices, as there was no room on the 3DS cartridge to include multiple voice tracks.[13]

To promote the game, Nintendo collaborated with multiple Japanese animation studios to create animated shorts based on the world and characters of Uprising. There were three shorts produced: the single-episode Medusa's Revenge by Studio 4°C, the two-part Palutena's Revolting Dinner by Shaft, and the three-part Thanatos Rising by Production I.G.[39] Sakurai supervised work on the animated shorts, but otherwise let the animators "do their own thing".[12] The shorts were streamed in Japan, Europe, and North America through the 3DS's Nintendo Video service in the week prior to the game's release in each region.[39][40][41] Limited packs of AR Cards were also produced by Nintendo in two series, including special packs featuring rare cards. Six random cards also came packaged with the game itself.[5][14][42]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 83/100[43] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| 1Up.com | B+[44] |

| Edge | 8/10[45] |

| Eurogamer | 9/10[46] |

| Famitsu | 40/40[47] |

| Game Informer | 7/10[48] |

| GameSpot | 8/10[49] |

| IGN | 8.5/10[50] |

| Nintendo Power | 9.5/10[51] |

| Nintendo World Report | 9.5/10[52] |

| Official Nintendo Magazine | 91%[53] |

Kid Icarus: Uprising received largely positive reviews from critics. On aggregate site Metacritic, the game scored 83/100 based on 75 critic reviews.[43] Famitsu gave the game a perfect score of 40 points. In its review, the magazine praised the attention to detail, flexibility, and general gameplay balance. It also positively noted the game's dialogue.[47] Marty Sliva, writing for 1Up.com, said that there was "a never-ending litany of things to love" about Uprising.[44] IGN's Richard George called Uprising "a fantastic game" despite its flaws.[50] Simon Parkin of Eurogamer said that "Kid Icarus: Uprising is a strong, pretty game turned into an essential one by way of its surrounding infrastructure".[46] GameSpot's Ashton Raze said that Uprising was a fun game when it hit its stride, calling it "a deep and satisfying shooter" despite its issues with control and character movement.[49] Neal Ronaghan of Nintendo World Report, while commenting on control issues, called Uprising an "amazing game" packed with content.[52]

Nintendo Power gave a positive review to the game.[51] Jeff Cork of Game Informer was more critical than other reviewers, saying that most other aspects of the game were let down badly by the control scheme.[48] Edge Magazine was positive overall, saying that fans of the original Kid Icarus would enjoy the game, praising the way it effectively combined elements from multiple genres.[45] Steve Hogarty of Official Nintendo Magazine recommended Uprising for hardcore gamers rather than casual gamers, saying that it felt deeper than equivalent home console games.[53] Opinions were generally positive on the lighthearted story, in-game dialogue, graphics, several aspects of gameplay, and its multiplayer options. However, a unanimous criticism was the control scheme, which was variously described as difficult or potentially damaging to players' hands, while also creating issues with moving Pit. There were also negative comments about the game's linear structure.[44][45][46][48][49][50][51][52][53]

During its first week on sale in Japan, Uprising reached the top of gaming charts with sales of 132,526 units. It also boosted sales of the 3DS to just over 67,000 from just under 26,000 the previous week.[54] By April, the game remained in the top five best-selling games with over 205,000 units sold.[55] Going into May, it was cited by Nintendo as a reason for increased profits, alongside other titles such as Fire Emblem Awakening.[56] As of December 2012, Uprising had sold just over 316,000 copies in Japan, becoming the 28th best-selling game of the year.[57] In North America, the game sold over 135,000 units, becoming one of the better-selling Nintendo products of the month.[58] In the UK, the game came in seventh place in the all-format gaming charts.[59] As of April 2013, the game has sold 1.18 million units, being the 10th best-selling title for the system at that time.[60]

Legacy

[edit]Despite speculation about a sequel for Uprising being developed, Masahiro Sakurai confirmed that there were no plans for a sequel to the game.[35] Upon being asked about a modern adaptation for the Nintendo Switch, he once again denied any possibilities, stating that it was difficult on a human resources level to maintain the development team as they were an ad hoc studio.[61][62] Uprising was the only game Project Sora ever produced; just four months after the game's release, the studio was closed with no explanation given for the closure,[63] while Sakurai and Sora Ltd. were beginning work on the next entry in the Super Smash Bros. series. Pit returned from Super Smash Bros. Brawl as a playable character in Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U, now sporting his slightly updated redesign from Uprising, while fellow Kid Icarus characters Palutena and Dark Pit joined the roster as playable newcomers.[64][65][66] The games' Classic Mode also incorporated a wager-based difficulty slider similar to the Fiend's Cauldron in Uprising,[67] and an Easter egg called Palutena's Guidance can be triggered that mirrors the dialogue from the original game. All of these elements were retained in the 2018 follow-up, Ultimate, for the Nintendo Switch.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Kid Icarus: Uprising Manual" (PDF). Nintendo. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Djordjevic, Marko (19 January 2012). "Kid Icarus' Last Stand". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Kid Icarus: Uprising Single Sheet Insert (PDF). Nintendo. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Romano, Sal (22 February 2012). "Kid Icarus: Uprising multiplayer detailed". Gematsu. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b "5 facts about Kid Icarus: Uprising AR Idol Cards". Nintendo UK. 11 May 2012. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ Gifford, Kevin (30 June 2010). "Masahiro Sakurai Discusses Kid Icarus: Uprising's Origins". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Narcisse, Evan (28 June 2010). "E3 2010: Masahiro Sakurai Makes Kid Icarus Fly Again on the Nintendo 3DS". Time. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Gifford, Kevin (14 July 2010). "More on The Making of Kid Icarus: Uprising". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Parish, Jeremy (7 September 2011). "Taking Flight: The Return of Kid Icarus". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Lucas M. (26 January 2011). "You Don't Know Kid Icarus". IGN. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b Gifford, Kevin (13 February 2013). "Kid Icarus creator: Stories in video games are 'honestly irksome to me'". Polygon. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d Loe, Casey (10 January 2012). "Kid Icarus: Uprising – Uprise and Shine". Nintendo Power. No. 275. Future US. pp. 34–42.

- ^ a b c d e f g Riley, Adam (19 June 2012). "Cubed3 Interview / Sakurai-san Talks Kid Icarus: Uprising (Nintendo 3DS)". Cubed3. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Iwata Asks: Kid Icarus Uprising". Nintendo. 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Causing an Uprising - Interview with Masahiro Sakurai". Nintendo Power. No. 279. Future US. 5 June 2012. pp. 20–22.

- ^ Project Sora (23 March 2012). Kid Icarus: Uprising (Nintendo 3DS). Nintendo. Scene: Credits.

- ^ a b Ashcraft, Brian (18 February 2009). "Smash Bros. Creator And Nintendo Announce New Title, New Company". Kotaku. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "Kid Icarus: Uprising interview: "We got rid of the level of difficulty", says Sakurai". GamesTM. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b Jenkins, David (26 March 2012). "Kid Icarus: Uprising interview – talking to Masahiro Sakurai". Metro. Archived from the original on 4 November 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ George, Richard (2 May 2012). "In Defense of Kid Icarus Uprising's Controls". IGN. Archived from the original on 3 August 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Schweitzer, Ben (28 June 2014). "Kid Icarus -Uprising- Original Soundtrack Commentary". Video Game Music Online. Archived from the original on 6 May 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Enjoy Some Tunes from Kid Icarus Uprising". Nintendo UK. 2012. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ Napolitano, Jason (13 August 2012). "Kid Icarus: Uprising OST available for special pre-order". Destructoid. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ "Shin Hikari Shinwa Palutena no Kagami Original Soundtrack". VDMdb. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ a b Acero, Julius (1 August 2012). "Kid Icarus -Uprising- Original Soundtrack". Video Game Music Online. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ Gann, Patrick (26 September 2012). "It Exists And It's Huge! Kid Icarus Uprising OST (Review)". Original Sound Version. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ Watts, Steve (15 June 2010). "E3 2010: Kid Icarus Uprising Announced for 3DS". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Sanchez, David (27 September 2011). "Kid Icarus Uprising Delayed". GameZone. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Gantayat, Anoop (20 January 2012). "Kid Icarus Uprising Goes Gold". Andriasang.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ 「新・光神話 パルテナの鏡」は2012年3月22日に発売決定。マルチプレイは3対3のチーム対戦,最大6人でのバトルロイヤルが可能. 4Gamer.net. 27 December 2011. Archived from the original on 4 October 2014.

- ^ Romano, Sal (13 December 2011). "Kid Icarus: Uprising release date set". Gematsu. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Orry, James (25 January 2012). "Kid Icarus: Uprising UK release confirmed for March 23". VideoGamer.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Kozanecki, James (25 March 2012). "AU Shippin' Out March 26–30: Kid Icarus: Uprising". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Romano, Sal (13 January 2012). "What's the difference between Kid Icarus: Uprising's U.S. and Japanese box arts?". Gematsu. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Drake, Audrey (9 May 2012). "No Sequel for Kid Icarus Uprising". IGN. Archived from the original on 22 November 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b Yip, Spencer (7 August 2013). "How Nintendo Made Mario & Luigi Funny And Other Tales From Treehouse". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ "Ginny McSwain - Resume". Ginny McSwain official website. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Madden, Orla (3 March 2013). "Interview: Meet Antony Del Rio - Voice Actor for Pit / Dark Pit". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Kid Icarus: Uprising - Watch Original 3D Animations". Kid Icarus: Uprising UK website. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ "Kid Icarus 3d Anime Videos". Nintendo Video. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ 『新・光神話 パルテナの鏡』、パルテナが主役のオリジナルアニメ「おいかけて」配信開始. Inside Games. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ "Kid Icarus: Upsing - Where To Find The AR Cards". Kid Icarus: Uprising US website. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Kid Icarus: Uprising". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ a b c Sliva, Marty (19 March 2012). "Kid Icarus Uprising Review: Stunning Despite Stumbling". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "Kid Icarus: Uprising review". Edge. 23 March 2012. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Parkin, Simon (19 March 2012). "Kid Icarus: Uprising Review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ a b 新・光神話 パルテナの鏡. Famitsu. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Cork, Jeff (19 March 2012). "Kid Icarus: Uprising - Poor Controls Ground Pit's Ambitious Return". Game Informer. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Ashton, Raze (23 March 2012). "Kid Icarus: Uprising Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015.

- ^ a b c George, Richard (19 March 2012). "Kid Icarus Uprising Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ a b c "Kid Icarus: Uprising – Here's Looking At You, Kid". Nintendo Power. No. 277. Future US. 4 April 2012. pp. 78–81.

- ^ a b c Ronaghan, Neal (19 March 2012). "Kid Icarus Uprising Review". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Hogarty, Steve (19 March 2012). "Kid Icarus Uprising review". Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ Leo, Jon (29 March 2012). "Big in Japan March 19–25: Kid Icarus: Uprising". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ Sahdev, Ishaan (11 April 2012). "This Week In Sales: Super Robot Taisen Launches, Kingdom Hearts Drops Like A Rock". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ Gantayat, Anoop (15 June 2012). "Nintendo Software Made the Most Money in May". Andriasang.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ Sahdev, Ishaan (25 January 2013). "The Top-30 Best-Selling Games In Japan In 2012 Were..." Siliconera. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ Goldfarb, Andrew (12 April 2012). "NPD: Mass Effect 3 Tops Charts". IGN. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ "FIFA Street fends off Raccoon City on UK Chart". GameSpot. 26 March 2012. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ Goldfarb, Andrew (24 April 2013). "How Many Copies Have Nintendo's Biggest Games Sold?". IGN. Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ "Sakurai doesn't think modern Kid Icarus: Uprising port would be possible". 8 December 2018. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ "A Kid Icarus: Uprising Sequel Would be "Difficult", Says Masahiro Sakurai". 22 March 2021. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ O'Brien, Lucy (11 July 2012). "Kid Icarus: Uprising Developer Closes". IGN. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ "Super Smash Bros Characters: Confirmed Character List For Smash Bros Wii U, Smash Bros 3DS". Digital Trends. 12 June 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Otero, Jose (10 June 2014). "E3 2014: Palutena Joins Super Smash Bros. 3DS, Wii U Roster". IGN. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Garratt, Patrick (11 September 2014). "Super Smash Bros. 3DS stream confirms new playable characters". VG247. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Sahdev, Ishaan (25 August 2014). "Changing The Difficulty In Super Smash Bros. Will Have Other Effects, Too". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

External links

[edit]- 2012 video games

- Augmented reality games

- Cooperative video games

- Cultural depictions of Medusa

- Fiction about deicide

- Fiction about sacrifices

- Kid Icarus

- Metafictional video games

- Multiplayer and single-player video games

- Nintendo 3DS eShop games

- Nintendo 3DS games

- Nintendo 3DS-only games

- Nintendo Network games

- Phoenixes in popular culture

- Rail shooters

- Self-reflexive video games

- Third-person shooters

- Video game sequels

- Video games about alien invasions

- Video games about cloning

- Video games directed by Masahiro Sakurai

- Video games scored by Masafumi Takada

- Video games scored by Motoi Sakuraba

- Video games scored by Noriyuki Iwadare

- Video games scored by Takahiro Nishi

- Video games scored by Yasunori Mitsuda

- Video games scored by Yuzo Koshiro