History of La Flèche

The history of La Flèche encompasses ancient and more recent events, with a particularly notable increase in occurrence in the modern era. Despite evidence of human habitation dating back to prehistoric, La Flèche was established relatively recently, around the year 1000. This period saw the construction of a fortress along the banks of the Loir, which would become a defining feature of the city's landscape. Its strategic location on a navigable waterway and at the crossroads of routes linking France's major western provinces resulted in its ownership by the Plantagenets, counts of Anjou, and kings of England, for some time. However, La Flèche was largely overlooked by its various lords at the end of the Middle Ages until Françoise d'Alençon retired there at the end of her life in 1537.

At the turn of the 17th century, La Flèche experienced a renewed surge in growth and prosperity, largely due to the favor and patronage of Henry IV, King of France, and Guillaume Fouquet de La Varenne. Under Fouquet's stewardship as the city's governor, La Flèche underwent significant modernization and emerged as a prominent administrative and judicial center. However, it was primarily the establishment of the Jesuit college in 1603 that marked the beginning of a period of great prosperity. One of its former students, Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière, played an important role in the spiritual renewal of La Flèche while also being one of the founders of the city of Montreal in Canada. In 1641 and then in 1653, hundreds of residents from La Flèche committed to founding a colony there.

La Flèche was marked by the passage of the Vendéens on two occasions during the Virée de Galerne in 1793. Following this, the area underwent a new development period when Napoleon I established the Prytanée National Military Academy there in 1808, utilizing the premises of the former college. The town was subsequently occupied by Prussian forces in 1815 and again in 1871. During the First World War, La Flèche suffered significant losses, with 339 of its residents killed.

Following the Second World War, La Flèche experienced a period of expansion through the annexation of two additional communes, while simultaneously maintaining a trajectory of economic growth. The conclusion of the 20th century saw the initiation of several substantial urban developments, including the expansion of the municipal administration building, the establishment of a bus station, and the refurbishment of the town center. These initiatives persisted into the 21st century with the construction of a recreational facility, a comprehensive sports complex, a new cinema, and the restoration of the Saint-Thomas church facades.

Occupation of the territory from Prehistory to the Early Middle Ages

[edit]

The archaeological record indicates that human occupation in La Flèche and its surrounding area dates back to the Neolithic period. This is evidenced by the discovery of numerous artifacts from this era, as well as several megaliths in the Loir Valley.[1][2] Among the discoveries were Campignian stone tools found near the area known as La Vallée, located to the north of the city.[cf 1] Another notable find is the menhir, or standing stone, called La Roche Voyer, which is situated within the commune, near the former Mélinais Abbey.[3][4] Despite these early indications of human activity, the region saw sparse settlement during this period. The town's development occurred much later, with only one trace of occupation during antiquity: a Gallo-Roman villa, or substantial farmhouse, on the site of the present-day Saint-Jacques district.[cf 2]

During this period, Cré, rather than La Flèche,[5] served as a crucial relay station for the cursus publicus, the Roman postal service, along the Roman road connecting Le Mans and Angers. Situated on the Champs Priory site, Cré provided a crossing point for the Loir via a ford.[cf 2] The occupation of Cré spanned a more extended period and was uninterrupted, with evidence of prehistoric settlement in the form of approximately fifteen Neolithic tools and indications of early Romanization,[cf 2] including the discovery of a Venus statuette, pottery shards, and Roman coins.[cf 1] Cré retained its significance through the Carolingian era, becoming the principal settlement of a condita (an administrative district) within a pagus (a county-like area)[6][7] and serving as the site of a mint in the seventh century.[cf 2]

Meanwhile, in La Flèche, the Gallo-Roman villa underwent a gradual transformation into a medieval village, with the establishment of a church on the site of the present-day Notre-Dame-des-Vertus chapel.[d 1] The early settlement of other peripheral areas of La Flèche has also been evidenced by the discovery, before World War II and again in 1990, of a set of thirteen Merovingian sarcophagi situated near the Grand-Ruigné hillside.[cf 3][Note 1]

From the founding of the city to the end of the Middle Ages

[edit]La Flèche was established shortly after the year 1000 and rapidly acquired a prominent position. In 1051,[cf 4] Jean de Beaugency, the younger son of Lancelin I, the lord of Beaugency, and Paula du Maine, the youngest daughter of Count Herbert I Wake-Dog,[9] sought a location in which to construct a castle within his domain of Fissa (fiscal land). He selected the area for his fortress, which was constructed on stilts, by fortifying several islands in the Loir at the site of the current Château des Carmes. Additionally, he built a bridge to redirect a portion of the commercial traffic from the medieval route connecting Blois to Angers, necessitating the payment of a toll by merchants utilizing the route. For this reason, Jean de Beaugency is regarded as the inaugural lord of La Flèche.[cf 2] The site rapidly acquired both strategic and commercial significance, situated on a navigable waterway and at the confluence of routes from Paris to Anjou and from Brittany to Touraine.[a 1] Moreover, Jean de Beaugency's position as a vassal to the Count of Anjou but related to the Counts of Maine through both his mother and his wife placed his territory at the center of disputes between the two counties.[b 1] In 1067, the army of La Flèche was referenced in the Chronicle of Saint-Aubin.[b 2]

In 1078, the town was besieged by the forces of Fulk IV, Count of Anjou, who was supported by Duke Hoël II of Brittany. Their objective was to oppose Jean de Beaugency's alliance with the Normans, who were considered enemies of the Anjou counts. William the Conqueror, King of England and Duke of Normandy, became involved in the conflict to defend his ally. However, open combat was averted through the intervention of several clergy members, including Bishop Odo of Bayeux, who facilitated a mediation process.[cf 5] The peace treaty was eventually concluded in an area near La Flèche, known as Blanche-Lande or Lande de la Bruère.[b 3][Note 2] This provisional cessation of hostilities did not fully reconcile the lord of La Flèche with Fulk IV of Anjou. In 1081[b 4] or 1087, the fortress was captured and burned.[cf 4] In that same year, Jean de Beaugency donated the chapel of his castle to the Benedictine monks of Saint-Aubin Abbey in Angers, as well as the church of Saint-Odon, located farther east in the neighboring parish of Sainte-Colombe.[10][cf 6]

His third son, Elias of La Flèche, succeeded him[cf 4] and became the first lord to bear the town's name. However, like most lords of that period, he only resided in the area a few days per year, as he moved between his various estates. The town's management and administration were delegated to seneschals, a role held by the Cleers family at La Flèche around the 12th century, for both Elias and his successors.[cf 4][b 5]

In 1093, Elias of La Flèche procured the county of Maine from his cousin Hugh V of Este. Additionally, he facilitated the town's expansion through the establishment of the Saint-Thomas church and priory in 1109, which was entrusted to the Benedictine monks of Saint-Aubin Abbey in Angers.[c 1] Upon his demise, he bequeathed only a daughter, Erembourg, who married Fulk V of Anjou, son of Fulk the Fat and future King of Jerusalem, circa 1110. This union definitively merged Maine with Anjou, including the seigneury of La Flèche. From that point onward, La Flèche remained under the control of the Plantagenet counts of Anjou, who also held the title of King of England. The town continued to flourish with the establishment of several religious institutions, including the Saint-André Priory, which was founded in 1171 by monks from Saint-Mesmin Abbey in Orléans. The monks were granted land by Henry II Plantagenet.[d 2] In 1180, Henry II, King of England, established Saint-Jean Abbey of Mélinais in the forest of the same name, located to the southeast of the town.[11] By the end of the 12th century,[b 6] the seigneury of La Flèche had passed to the Beaumont family, through Raoul VIII of Beaumont-au-Maine. However, the circumstances surrounding this succession remain unclear.[cf 4][a 2]

In 1224, La Flèche was elevated to the status of archpriesthood.[cf 6] In 1230, a few years later, King Louis IX of France stayed in La Flèche for two days while French troops, under orders from regent Blanche of Castile, marched on Brittany with the objective of ending the alliance between Duke Peter I and Henry III of England. Notably, Louis paid homage to the statue of Notre-Dame-du-Chef-du-Pont in the chapel of the same name, which is located at the entrance to the Carmes bridge over the Loir and adjoins the castle.[d 3] This modest, transept-less edifice had also been visited by Thomas Becket nearly a century earlier[c 2] and remained a significant pilgrimage site in the region. At the beginning of the 15th century, the clergy of Saint-Thomas organized a procession there during the Notre-Dame festivals.[cf 4]

In 1386, during the Hundred Years' War, the English besieged and burned La Flèche Castle. The fortress was occupied by the English until 1418, during which time it was besieged on numerous occasions.[cf 4]

In 1431, a dispute arose between John II, Duke of Alençon, and his uncle, the Duke of Brittany, concerning the dowry of Mary of Brittany, the latter's mother. The matter in question pertained to the lack of a fully settled agreement regarding the aforementioned dowry. Subsequently, John II had the chancellor of the Duke of Brittany, Jean de Malestroit, arrested and held him prisoner at the Château de La Flèche and then at that of Pouancé.[b 7][12] In the subsequent years, the territory of La Flèche was elevated to the status of a barony. On September 10, 1453, John II of Alençon, the lord of the region, made a declaration to René of Anjou, outlining its various titles, rents, and properties.[b 8] His son, René of Alençon, established a Third Order Franciscan monastery in the area in 1484, followed by a Cordeliers convent four years later.[b 7]

Modern era

[edit]The Château-Neuf of Françoise d'Alençon

[edit]

Until the mid-16th century, La Flèche was a city that was largely ignored by its lords, who rarely or never resided there. Local historian Charles de Montzey characterized the city as "shrouded in obscurity" and "open to all comers."[a 1] Following the death of her husband in 1537, Françoise d'Alençon elected to take up residence in this lordship, which she had inherited from her parents and received as part of her dowry from her husband, Charles IV of Bourbon.[cf 7] At that time, the feudal Château de La Flèche, constructed on the Loir, was in a state of advanced deterioration and lacked comforts. Françoise d'Alençon transferred it to the religious congregation of the Carmelites (from which it derives its current name) and initiated the construction of a new residence, the Château-Neuf, situated at the location of the present Prytanée National Military, slightly north of the original castle, beyond the city walls. The architectural design was assigned to the renowned Jean Delespine, who oversaw its construction between 1539 and 1541.[e 1][a 3]

In 1543, she secured from the King of France, Francis I, the elevation of multiple baronies, including that of La Flèche, to a duchy-peerage, designated as the Duchy of Beaumont.[cf 7] She died in La Flèche in 1550, leaving her possessions to her son Antoine of Bourbon and his wife Jeanne d'Albret. The couple regularly resided there between February 1552 and May 1553, leading some local historians to posit the hypothesis that their son, the future King Henry IV of France, born on December 13, 1553, may have been conceived in La Flèche. Jules Clère, therefore, characterizes him as "Fléchois before being Béarnais."[a 4] Although this claim is largely based on anecdotal evidence, the "conception" of the future king is purported to have occurred at the Hôtel d'Ailly in Abbeville, where Antoine of Bourbon and Jeanne d'Albret stayed for an exact nine months before his birth.[cf 8][13] Henry IV subsequently demonstrated a distinct affinity for the town throughout his reign. During his youth, he also made brief visits there, notably in 1562 and 1576.[14][a 5]

In 1589, the year of his ascension to the throne, La Flèche was besieged by Lansac, a captain of the Catholic League. However, he was subsequently recaptured by the Marquis of Villaines a few days later.[d 4]

Henry IV and Fouquet de La Varenne, benefactors of La Flèche

[edit]The end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century saw a resurgence in the fortunes of the city. The ascension of Henry IV to the French throne permitted the seigneury of La Flèche, along with other territories belonging to the Duchy of Beaumont, to be incorporated into the Crown.[cf 4] Guillaume Fouquet de La Varenne, hailing from a bourgeois family in La Flèche, entered the service of Catherine of Bourbon, the sister of the future King Henry IV, in 1578. Two years later, he became the chamberlain of the future King of Navarre.[15] Until Henry IV's assassination in 1610, de La Varenne remained a close advisor and was involved in significant events during his reign.[15]

Lord of La Varenne, also known as La Garenne or Bois des Sars, located north of the city in the commune of Bousse, he assumed the role of governor of La Flèche and captain of its castle in 1589. From this date forward, he oversaw a series of beautification and transformation works, including the restoration of the fortifications between 1593 and 1596, the rebuilding of the bridge over the Loir between 1595 and 1600, the renovation of the market halls, and the commencement of street paving in 1597.[cf 9] He established tax-free fairs and granted the residents of La Flèche the right of "apetissement" on wines and beverages sold within the walls.[c 3] At an undetermined date, he became the first "engagiste" lord of La Flèche, and Sainte-Suzanne in September 1604. In 1616, he was created the First Marquis of La Varenne, and proceeded to construct a château in the city, which extended from the banks of the Loir to the current rue de la Tour d'Auvergne and Grande-Rue.[cf 9]

Meanwhile, in 1595, Henry IV signed the edict establishing a presidial seat at La Flèche, thereby centralizing cases for the lordships of Beaumont, Château-Gontier, Mamers, Sainte-Suzanne, and Le Lude, with the establishment of a provost court.[cf 9][c 3] From an administrative perspective, La Flèche's seneschaly was attached to Anjou, and the city was home to one of the province's sixteen salt warehouses. Additionally, it became the seat of an election encompassing over a hundred parishes.[Note 3][a 6] In 1598, the king made another brief visit to La Flèche to meet with Gabrielle d'Estrées.[cf 4] By 1600, the local population was estimated to be 3,000 inhabitants.[cf 10] La Flèche was a city with minimal commerce and industry, primarily sustained by numerous officials from administrative and judicial organizations.[a 7]

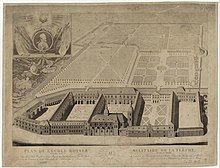

On September 3, 1603, the king signed the Edict of Rouen, which authorized the return of the Jesuits to France. He subsequently decided to give them his Château-Neuf in La Flèche, to establish a college there.[15] This was the foundation of the Royal College Henri-le-Grand, which soon gained considerable renown throughout the kingdom. Among the inaugural cohort of students at this nascent institution were the philosopher René Descartes, the first bishop of Quebec François de Montmorency-Laval, and the mathematician and philosopher Marin Mersenne.[17]

In 1607, Henry IV confirmed his attachment to the La Flèche college by issuing the Edict of Fontainebleau, which stipulated that his heart be placed in the college church after his death.[18] In the aftermath of the monarch's demise, Guillaume Fouquet de La Varenne drew Queen Marie de Medici's attention to the pledge made by Henry IV. Subsequently, the monarch's heart was placed in the care of the Jesuits and conveyed to La Flèche, where the procession commenced on the morning of June 4, 1610, with the Duke of Montbazon at the helm.[18] Subsequently, a ceremony was conducted at Saint-Thomas Church before the transfer of the heart to the Royal College. In June 1611, the Jesuit fathers organized the Henriade, a three-day festival featuring a play depicting France in mourning over the king's tomb, along with readings in prose or verse and a procession that maintained the memory of Henry IV in the town.[19] According to Henry IV's wishes, the heart of Marie de' Medici was added alongside that of her former husband in the Royal College chapel on April 12, 1643.[19]

Following the king's demise, the college continued to expand, reaching a maximum enrollment of 1,800 students by 1626.[e 2] In 1612, Marie de' Medici dispatched Father Étienne Martellange to La Flèche to supervise the conclusion of the church's construction, with costs borne by the royal treasury.[20] On September 3, 1614, the young Louis XIII and the regent visited La Flèche and were greeted at the College.[20] On this occasion, Guillaume Fouquet de La Varenne arranged a lavish celebration, including a ballet featuring 800 dancers at his château.[21]

In September 1615, the monarch enacted an edict that formalized the establishment of the municipality of La Flèche.[cf 9] The following year, the lands of La Varenne were incorporated into the municipality and elevated to the status of a marquisate.[15]

From La Flèche to Montreal, the work of Jérôme Le Royer de la Dauversière

[edit]

From its inception, the College hosted among its faculty Jesuit missionaries who had returned from New France, such as Énemond Massé, whose accounts held a particular fascination for students.[i 1] Jérôme Le Royer de la Dauversière was born in La Flèche in 1597 and attended the College until 1617. He then succeeded his father as tax receiver.[h 1] He was renowned for his piety and claimed to have received a mystical vision on February 2, 1630, while engaged in prayer before the statue of Notre-Dame-du-Chef-du-Pont in the old chapel of the Carmes Castle. He was inspired to found a religious hospital congregation dedicated to serving the poor and sick.[i 2] In the subsequent years, he encountered Marie de La Ferre, with whom he established the Hospitaller Sisters of St. Joseph in La Flèche on May 18, 1636.[h 2][i 3] He was financially supported by Pierre Chevrier and obtained the property of the Island of Montreal from Father Jean de Lauzon in 1640.[h 3] In the following year, he proceeded to establish the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, in collaboration with Jean-Jacques Olier and Pierre Chevrier. The objective of this endeavor was to found a fortified city in New France, to provide education to the indigenous population. During this period, he also met Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve in Paris, who expressed his willingness to join the project and provide financial support. Jérôme Le Royer subsequently initiated the process of recruiting individuals willing to undertake the journey.[h 4]

In July 1641, approximately fifty men set sail from Port Luneau in La Flèche for New France, via Nantes and La Rochelle, under the command of Maisonneuve. Many Hospitaller Sisters of Saint Joseph, including Jeanne Mance, accompanied the group to establish the Hôtel-Dieu of Montreal. Upon reaching Quebec, the colonists spent the winter there before embarking on their journey up the Saint Lawrence River. They reached the island of Montreal on May 17, 1642, and proceeded to establish the settlement of Ville-Marie.[h 5][i 4] In late 1651, Maisonneuve returned to France intending to recruit number of men to guarantee the long-term viability of the colony. Consequently, between March 23 and May 17, 1653, La Flèche witnessed the enlistment of over a hundred men for New France in what became known as the "Grand Recruitment."[h 6][cf 11] The majority of these men originated from La Flèche or neighboring villages. Of the 121 recruits from La Flèche, only 71 ultimately departed from Saint-Nazaire on June 20.[cf 11] Despite being recognized as one of the founders of Montreal, Jérôme Le Royer de la Dauversière, the driving force behind the project, never traveled to New France. Instead, he dedicated himself primarily to the advancement of his congregation.[i 5]

La Flèche from the 17th to the 18th century

[edit]

In 1620, La Flèche witnessed another royal visit. Louis XIII, who had ousted his mother from the regency three years earlier, led the royal army against her forces in an attempt to regain power with the support of several major nobles. The king and his army entered the town on August 4 and left on August 6, subsequently securing a decisive victory at the Battle of Ponts-de-Cé.[cf 4]

In the following year, the monarch bestowed the antiquated château on the Loir and its chapel, Notre-Dame-du-Chef-du-Pont, upon the Carmelite Fathers. This was done with the stipulation that the ruins on the Loir be cleared. The Carmelite Fathers' convent had previously been located on rue des Plantes. The Fathers subsequently obtained the requisite authorization to extend the chapel and construct new buildings to extend the convent, and to build a cloister over the old arches. The Carmelite Fathers' presence in La Flèche was motivated by Father Philippe Thibault's aspiration to facilitate the training of newly professed members, capitalizing on the Jesuits' presence in the city. The Carmelite Fathers, responsible for naming the castle, undertook a restoration project that enhanced its comfort, establishing it as one of the most notable residences in the area.[cf 4]

During this period, the town acquired a reputation for its piety, earning the sobriquet "Sainte-Flèche" on account of the numerous convents within its boundaries. From the 17th to the 18th century, La Flèche was home to approximately a dozen religious congregations, in addition to the Jesuits who administered the local college. By the late 17th century, the town had a population of approximately 300 male and female religious members.[cf 9] Among these, the Capuchins took up residence in La Flèche in 1635 at the behest of a prominent local figure, Jouy des Roches,[b 9] while the Visitandines established themselves in 1646 and founded a monastery that subsequently became the town's hospital following the French Revolution.[cf 12]

Throughout the seventeenth century, a series of conflicts emerged between the Jesuits and the lords of La Flèche.[22] In 1630, René I Fouquet de La Varenne, the second son of Guillaume and the second Marquis de La Varenne, initiated a conflict with the Jesuits. The dispute arose from his assertion of his right to fish in the moat of the College and his refusal to pay the Jesuits the 12,000 livres that his father had bequeathed to them. Due to the Jesuits' unyielding stance, René and his companions resorted to armed conflict, resulting in the closure of the College for several days. After four years of legal proceedings, the dispute was resolved when the Jesuits paid the marquis a thousand écus, marking the conclusion of the conflict, which came to be known as the "Frog War."[22]

There were also other significant occurrences during this period. Between 1648 and 1649, François de Vendôme, who was known as the "King of the Markets"[23] and was the grandson of Henry IV and Gabrielle d'Estrées, was concealed at the rectory of La Flèche by the parish priest Pierre Hamelin after he escaped from Vincennes Castle, where he had been imprisoned for five years due to his involvement in the 1643 Cabal of the Importants against Cardinal Mazarin.[c 4] In 1690, the town council established a citizens' militia to ensure the town's safety. To form it, the city was divided into four districts, each supplying a company of 100 men led by a captain, a lieutenant, and an ensign. The entire militia was commanded by a major and an aide-major, and it remained active until the French Revolution.[a 8]

Concurrently, the town's economic development proceeded apace. La Flèche occupied a strategic position at the intersection of a route connecting the Perche region to the Loire Valley via the Loir Valley. The town's trade was considerable, with shipments of wood from the Bercé Forest, building materials, and wines from Anjou.[24] By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the town population had reached 5,200.[25] The old wooden market halls were rebuilt in stone on two occasions, initially in 1737 and subsequently in 1772, to accommodate the town hall.[a 9] This initial construction was promoted by François de la Rüe du Can. He served as mayor from 1735 to 1745, a tenure marked by remarkable longevity and commendable actions in assisting those affected by the severe Loir River flood of 1740. His rapport with the townspeople was so strong that at the conclusion of his first term, they petitioned the king for his reappointment. In addition to this, François de la Rüe du Can was also ennobled in 1743.[a 10]

In 1762, following the expulsion of the Jesuit order from the kingdom, the College of La Flèche was temporarily closed, as were all other Jesuit institutions in France.[26] Facing the threat of closure, the College of La Flèche was saved from this fate by the municipality, which appointed a group of abbots to oversee its operations. Two years later, King Louis XV signed letters patent to establish a "Royal Military College" at the institution, which served as a preparatory cadet school for the Royal Military School at Champ de Mars. In 1776, the college became the "Royal and Academic College" when Louis XVI appointed the Doctrinarian Fathers to oversee its management.[cf 13]

Revolution and the First Empire

[edit]A town on the margins of the early Revolution

[edit]

In 1790, the French departments were established, and La Flèche, along with seventeen other parishes from the former province of Anjou, was incorporated into the Sarthe department.[d 5] The department was subdivided into nine districts, one of which was La Flèche. Two residents, Louis Rojou and François-Louis Rigault de Beauvais, were appointed as administrators of the department. The former was elected to the Sarthe Directory on July 21 of the same year, and then as Sarthe's deputy to the Legislative Assembly in September 1791.[27] Despite the town's peripheral position about major events and disturbances in the Revolution's early years, revolutionary ideas were relatively well-received in La Flèche.

A delegation from the town, comprising the surgeon Charles Boucher and a group of students from Henri IV College, was dispatched to Paris for the Festival of the Federation on July 14, 1790. During this period, the municipal council, under the leadership of Pierre de la Rüe du Can, encouraged residents to embrace the "new order of things."[27] The freedom of the press, enshrined in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, facilitated the proliferation of local and national newspapers, culminating in the advent of Les Affiches de La Flèche in early January 1791. The inaugural town newspaper, printed by Louis-Ignace de La Fosse, comprised eight pages and was published twice weekly. Despite its support for the Revolution, the publication maintained a relatively moderate tone and primarily served as a source of national news.[28] By the end of July 1791, a revolutionary club was established in La Flèche, a development that occurred later than in other main towns in the department. On September 8, the "People's Society of La Flèche" requested affiliation with that of Le Mans.[29]

Despite the emergence of counter-revolutionary disturbances in the rural areas surrounding La Flèche and southern Sarthe beginning in August 1791, the guillotine was only utilized on one occasion, on November 28, 1792, for the execution of a counterfeiter named Julien Rouillard.[27][cf 14]

The Vendéens in La Flèche (1793)

[edit]In 1793, the Vendée insurrection commenced in response to the mass conscription decree issued by the National Convention. The mobilization order was received in La Flèche on March 17.[30] On the following day, three companies of National Guards departed the city, comprising a total of 200 men who were armed with two bronze culverins from the Varenne castle. They joined the contingents from Lude and Baugé and proceeded towards Saumur, arriving on March 19.[30] After a brief one-month campaign, the National Guards returned to La Flèche. Subsequently, they were called upon once more to quell revolutionary unrest in the region, including in Mézeray on May 19 and in Brûlon on September 19.[27]

On June 24, five royalist horsemen, led by an individual identified as "Maignan", arrived in the town from Angers in the early morning hours. Armed with sabers, bearing a fleur-de-lis flag, and donning white cockades, they proceeded to the town hall and proclaimed the imminent arrival of 15,000 Vendéens. Subsequently, they proceeded to the detention center, which was situated in an annex of the Varenne castle. There, they liberated the sole prisoner and procured a horse from the college stables for him to join the procession.[30] Eyewitnesses, including surgeon Charles Boucher, reported that the initially stunned population of La Flèche subsequently became enthusiastic, with cries of "Long live the King" resounding throughout the city. The Tree of Liberty, planted in Revolution Square,[Note 4] was set on fire.[30] Later that day, municipal officers realized that they had made a mistake when a peddler from Angers informed them that he had not encountered any troops on his way. The Vendéens, who had taken refuge at the Hôtel du Lion d'Or,[Note 5] could escape before they were arrested.[30][27]

In September, the decision was made to terminate the La Flèche college's status as a military school. This entailed the destruction of the institution's principal emblems, paintings, and statues, which were perceived to evoke the Ancien Régime. A cobbler's workshop was established in its place to serve the army.[27] On September 24, Thirion, the commissioner in mission, ordered the burning of the hearts of Henry IV and Marie de' Medici, preserved in the Saint-Louis church. The ashes were collected by surgeon Charles Boucher and subsequently returned to the Prytanée military school in 1814 by his heirs. In a similar manner to the rest of France, La Flèche organized a Cult of Reason on November 10 in this same church, which was renamed the Temple of Reason.[27]

The inhabitants of La Flèche observed the passage of the Vendéens on two occasions during the Virée de Galerne. As the Vendéen army retreated across the Loire following the unsuccessful siege of Granville,[31] they entered La Flèche on November 30 without encountering any resistance. This was since the National Guards had dispersed and the local authorities had taken refuge in Thorée and Broc. For two days, the Vendéens seized goods from the city's stores and requisition supplies from residents. On December 2, the Vendéen troops departed for Angers.[30]

Due to the destruction of all bridges before Saumur by Convention orders, the Vendéens could not cross the Loire and were compelled to turn back. They then sought to reach Le Mans. On December 7, the Vendéens presented themselves before La Flèche, where they encountered a reinforced National Guard and 3,000 Republican troops from Le Mans, led by generals Chabot and Garnier de Saintes. To impede the Vendéens' advancement, the Carmes bridge was destroyed, with the defensive forces situated on the right bank of the Loir River. Following a two-hour engagement between the vanguard of the Vendéens and the Republican forces, La Rochejaquelein arrived at the city with the main army. He then directed the construction of a rudimentary crossing over the destroyed bridge, enabling 300 cavalrymen to ford the river downstream from the Bruère Mill and thereby gain a flanking position against the defenders. The Vendéens occupied the town, forcing the Republicans to retreat to Foulletourte. The wounded were relocated to Saint-Thomas Church. On the following day, the crossing of the Carmes bridge was restored. The Vendéens remained in La Flèche until December 10 to procure supplies, with looting becoming a pervasive phenomenon.[30] Upon their departure, Republican forces under General Westermann entered the town and pursued any remaining stragglers, some of whom were executed. The wounded and sick who were left behind in La Flèche were massacred. According to Republican generals, approximately 1,000 Vendéens died in La Flèche or its vicinity.[32] In the aftermath of the Vendéens' defeat in Le Mans on December 13 and subsequently in Savenay on December 23, the people of La Flèche endured a protracted period of hardship. The extensive looting that followed led to a state of famine, while a dysentery epidemic, introduced by the Vendéens and exacerbated by the decomposing corpses, spread rapidly.[30] On December 28, Garnier de Saintes dispatched grain to the La Flèche district to address the food shortage. Concurrently, Marat Roustel, the general prosecutor of Sarthe, initiated an investigation into the questionable conduct of local officials during the Vendéen incursion.[27]

From the reign of Terror to Napoleon's Coup d'État

[edit]

Joseph Panneau, a simple cobbler, was appointed mayor by Garnier de Saintes, a representative passing through La Flèche. Panneau was a staunch revolutionary who undertook a series of anti-religious actions, including the dismantling of crosses and the melting down of the bells of Saint-Thomas Church. He proceeded to target the College, stating, "It is no longer necessary for us to maintain this institution; it will be sold and demolished, and the land will be used for agricultural purposes."[a 11] On May 13, 1794, the College was ordered to be completely closed, despite objections from other municipal members. However, the premises did not remain unoccupied for an extended period. From September 1794 to November 1796,[27] a military hospital was established there, along with a cobbler's workshop in the historical paintings gallery, which is now the Prytanée library.[a 11] Panneau vacated the mayoral post shortly after the conclusion of the Terror, being succeeded by the former police lieutenant François-Louis Rigault de Beauvais.[a 11] In early December 1794, the National Guard of La Flèche was requisitioned by representative Génissieu for the purpose of combating the Chouan uprising.[27] A number of bands, including one led by Jean Châtelain, who was known as Tranquille, were active in the La Flèche region. On March 18, 1795, generals Leblay and Varrin, representing the armies stationed on the Brest and Cherbourg coasts, along with La Flèche's mayor, Rigault de Beauvais, signed a peace treaty with the primary Chouan leaders in the region. However, the subsequent resumption of unrest resulted in the town being attacked on April 2.[cf 15]

In 1799, the Republic's military reversals resulted in the formation of new levies and the enactment of the law on hostages, which prompted the Chouan leaders to resume their insurrectionary activities. Louis de Bourmont assumed command of the forces in Maine and directed François de La Motte-Mervé to enlist personnel from the La Flèche region, his hometown.[33] On September 2, a minor engagement occurred near the Pilletière castle, situated just north of La Flèche. The engagement involved a contingent of 400 royalist troops under the command of La Motte-Mervé and a detachment of 90 soldiers from La Flèche's mobile column. After several hours of combat, reinforcements arrived for the Republicans in the form of the National Guard, which prompted the royalists to withdraw without sustaining any losses.[33] For several days, the Republicans pursued La Motte-Mervé's forces along the Loir Valley, subsequently advancing north through Indre-et-Loire before returning to Sarthe and crossing the Loir at La Bruère on September 11.[33]

Meanwhile, a general uprising was being organized, with a simultaneous attack on major western towns by the royalists scheduled for October 15. Count Bourmont, with 4,000 men under his command, established a camp near La Flèche and contemplated an assault on the inadequately defended town. However, La Motte-Mervé dissuaded him, contending that such an attack would unnecessarily protract their advance toward the departmental capital. This intervention averted combat with the townspeople, although La Motte-Mervé was killed shortly thereafter in the Battle of Le Mans, where the town was captured by the Chouans.[33]

Following the 18 Brumaire coup, which saw the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, and the subsequent subsidence of unrest in the West, local administration began to take shape. La Flèche was designated a subprefecture of Sarthe under the law of 28 Pluviôse, Year VIII, which established the arrondissement divisions.[34]

Under the Empire: Establishment of the Prytanée Military School and Minor Chouannerie

[edit]

In a recent decree, Emperor Napoleon I has ordered the restoration of the Château de Fontainebleau for his personal use. Subsequently, the distinctive imperial academy is relocated to the Prytanée military school in Saint-Cyr. Consequently, the Prytanée must also relocate. The municipal authorities of La Flèche, aware of this undertaking, express their interest in hosting the establishment.[e 3] Mayor Charles-Auguste de Ravenel presents a historical and descriptive account of the Henri-IV college, concluding with a petition to the emperor, which is met with a favorable response. The decree establishing the Prytanée national military school was signed in Saint-Cloud on March 24, 1808, and the transfer was scheduled for June 1 of the same year.[e 3] General Bellavène, Inspector General of Military Schools, is charged with reporting on the material condition of the establishment and undertaking the most urgent repairs to accommodate the 240 students that the school will have at its opening on June 15.[e 3][e 4] In the initial period following its establishment, the Prytanée encountered significant financial challenges and a shortage of boarding students.[e 5] To address these shortcomings, Napoleon initially dispatches scholarship students from the Collège de la Marche in Paris, whose families had settled in the colonies, and subsequently, children from noble families in the territories that had been annexed by the Empire.[e 6] In 1812, an artillery school with an enrollment of 120 students is also incorporated into the Prytanée, thereby reinforcing the institution's prominence within the community.[e 6]

In 1813, Bernard de la Frégeolière, a leader of the Chouan movement, established two companies of approximately one hundred men in the regions of Sarthe and Maine-et-Loire. These companies, designated as the Nouveau-Nés, were clandestinely organized with the objective of uniting those who were resisting military conscription and impeding the collection of taxes. Those in support of the monarchy are experiencing a resurgence of optimism regarding its return. In response to these developments, the sub-prefect of La Flèche directs the National Guard to pursue the insurgents. At the beginning of 1814, a confrontation occurred in the village of Crosmières, a few kilometers from La Flèche, resulting in the death of eight National Guardsmen and one member of the Nouveau-Nés.[b 10][35] A few days later, Bernard de la Frégeolière was successful in securing the release of seven Nouveau-Nés who had been arrested in Sablé and imprisoned in La Flèche.[b 11]

The following year saw the return of Napoleon I during the Hundred Days, which marked the beginning of a new uprising in western France. This new uprising was known as the small chouannerie. General d'Andigné, who was in command of the royal army on the right bank of the Loire, proceeded to organize the various commands. The La Flèche district is the site of numerous clashes, with the local gendarmes particularly engaged with royalists in the Courcelles forest. These clashes result in the deaths of several of the royalists. Nevertheless, the town itself is not threatened; it is the town of Lude that is taken on June 9 by royalist troops under the leadership of General d'Ambrugeac and Bernard de la Frégeolière.[b 12] Following the emperor's second abdication on June 22, La Flèche is occupied for several weeks, from early July to August 2, by Prussian troops belonging to the 10th Hussar Regiment.[b 13]

The 19th century (1815-1914)

[edit]The city modernizes

[edit]

The appearance of the town underwent a notable transformation at the advent of the 19th century. The Choiseul-Praslin family, the heirs to the Château de la Varenne following the extinction of its last descendants, exhibited a striking lack of interest in the property and ultimately sold it to merchants.[a 7] The castle was entirely dismantled between 1818 and 1820, with its stones being repurposed for the construction of new residential buildings along the Grande Rue.[c 5] In 1827, restoration and extension work commenced on the Halle-au-Blé, which also housed the town hall. The project was completed twelve years later with the development of a small Italian-style theater on the first floor of the building.[a 12] In 1849, the ramparts that surrounded the town were dismantled.[b 14]

The modernization of La Flèche is a project that continues under the guidance of François-Théodore Latouche.[Note 6] Notable urban development projects are initiated and completed during this period. These include the reconstruction of the Carmes bridge, the completion of the development of the quays and the city center, and the opening of the "boulevard du Centre", which is now known as boulevard Latouche.[36] In 1857, a bronze statue of Henri IV, created by the sculptor Jean-Marie Bonnassieux, was erected at the center of the square that now bears his name.[c 4] The residents of La Flèche experienced a notable improvement in their quality of life with the advent of gas lighting in 1869, which was followed by the introduction of the telephone in 1897. On June 1, 1801, the inaugural ceremony for the city's first drinking water distribution network was held, presided over by President Émile Loubet.[f 1][cf 16] Concurrently, the city's boundaries expanded with the incorporation of the neighboring commune of Sainte-Colombe in 1866. This decision, which initially meets with considerable opposition, is partly motivated by the establishment of a railway station on the territory of this commune in 1863. Similarly, the neighborhoods of Beufferie and Bomieray, belonging to Sainte-Colombe, had long been regarded as suburbs of La Flèche, being separated from the town only by the Carmes bridge.[a 13][d 6]

On several occasions during the 19th century, the Prytanée, which had been renamed the "Royal Military School" during the Restoration, faced the threat of its complete dissolution. In June 1829, Deputy Eusèbe de Salverte proposed the abolition of military schools with the objective of allowing all French people to attain the rank of officer, rather than limiting this opportunity to students from these schools. He also recommended a significant reduction in the budget of the La Flèche establishment.[cf 13] The Prytanée was again the subject of debate in November 1830, when Corneille Lamandé, a deputy from Sarthe, defended the institution. However, the Minister of War of the nascent July monarchy, Marshal Gérard, proposed the suppression of the school in a report to democratize the recruitment of students from the special school of Saint-Cyr directly into the regiments. Nevertheless, the Royal Military College was re-established by ordinance on April 12, 1831. However, the institution continued to be the subject of recurrent attacks in the Chamber of Deputies. In order to maintain the institution, members of the municipal council of La Flèche take action and, in 1836, send each deputy a memorandum that presents the numerous and powerful considerations that should oppose the suppression of the College. While the establishment is retained, successive ministerial decisions during the July Monarchy reduce its budget. It is not until the early Second Empire that the school, renamed "Imperial Military Prytanée" by decree of May 23, 1853, appears definitively saved. Two months later, Marshal de Saint-Arnaud, Minister of War, visits the institution.[cf 13]

The "Prussians" in La Flèche in 1871

[edit]From the outset of the Franco-German War of 1870, an ambulance was established at the Prytanée to provide care for the wounded. The facility has the capacity to accommodate up to 670 military personnel.[e 7] Following the defeat of General Chanzy at Le Mans on January 11 and 12, 1871, the French and German positions became relatively fixed, with La Flèche situated at the limit of the German advance. The decision is made not to establish a permanent presence in the town due to concerns about the proximity of French troops under General Félix de Curten in nearby Durtal and Baugé. However, the town remains subject to frequent troop movements. On several occasions, the Germans engage in combat with the remaining francs-tireurs and mobile soldiers in the region, continuing until the armistice of January 28, or even beyond.[37][38]

The initial incursion into La Flèche is scheduled to commence on January 18. On that day, an infantry column commanded by Captain Hildebrand arrives with the objective of procuring hay and fresh horses. That same evening, the soldiers departed for Le Mans, with a portion of them spending the night on the heights of Saint-Germain-du-Val.[37] Three days later, a corps of 2,700 men from the 24th and 52nd Brandenburg regiments, under the command of the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg, entered the town. Communication with the outside world is suspended, while housing and food are requisitioned. Prussian soldiers dispatched on reconnaissance toward Bazouges and Clefs are subjected to fire from French francs-tireurs who have been ambushed. This prompts the general to construct three barricades to safeguard the town during the night.[37]

The German contingent commenced its withdrawal the following day but subsequently returned to La Flèche on January 24. A column of 1,500 men is positioned on the heights of Saint-Germain-du-Val, while an advance guard of cavalry is dispatched into the town to procure provisions. Simultaneously, a contingent of approximately fifty French troops, arriving from Durtal, enters La Flèche. The German cavalry withdrew from the area while apprehending the mayor, Philippe-Louis Grollier, two municipal councilors, and three members of the town hall staff as prisoners.[38] With the support of their artillery, the Germans were able to regain control of the situation. The town is subjected to a barrage of artillery fire, resulting in the mortal wounds of two individuals, including Second Lieutenant Richard, a Prytanée student who commands this detachment.[39][e 8] Subsequently, the Germans issued an ultimatum, threatening to burn the town if the French troops did not withdraw. This they did, ultimately.[38] The Germans continue their advance towards Bazouges, and for two days, fighting continues in the countryside south of La Flèche, around the road to Clefs and the woods of Petit-Ruigny. French soldiers, having sought refuge in various farms, are dislodged and suffer heavy losses. Four wounded French soldiers are also taken in and treated at the Château du Doussay, which has been converted into an ambulance facility.[37]

On the date of the armistice, January 28, shots were fired at the Prussians in the Boirie district. The evacuation of the city commenced on February 1. However, the resistance on January 24 resulted in a war contribution of 50 francs per inhabitant, amounting to a total of 350,000 francs. This figure was subsequently reduced following the mayor's appeals.[37]

La Flèche in the Belle Époque

[edit]

The railway reached La Flèche in 1871 with the inauguration of the Aubigné line, subsequently undergoing a substantial expansion in the early 20th century. As a result of the railway's arrival, the commune became a focal point for rail traffic, leading to the subsequent development of the station district on the left bank of the Loir. The five branches of this hub, which were managed by the Paris-Orléans company, proceeded towards Sablé, La Suze, Aubigné, Angers, and Baugé. In the years following the introduction of rail services, the decision was taken to construct a tramway line between Cérans-Foulletourte and La Flèche. This was intended to provide a direct link between Le Mans and the commune. This line was inaugurated on June 27, 1914, by the Sarthe Tramway Company.[f 2] Despite this, the city's economic prosperity remained relatively limited. At the beginning of the 20th century, economic activity was concentrated around the starch, shoe, and tannery industries.[40]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Prytanée had approximately 400 students and over a hundred officers, non-commissioned officers, teachers, and administrative personnel. However, the institution was confronted with a critical assessment from Deputy Flaminius Raiberti, who characterized it as a relic of the past. The school was staunchly defended by Fléchois Paul d'Estournelles de Constant, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1909, and Deputy Antoine Jourde, a former student of the school. Ultimately, the school was maintained.[f 3] The presence of the school, along with the barracks of La Tour-d'Auvergne, inaugurated in 1877, imbued the city with a distinct military character. A number of battalions were stationed at the facility, including a battalion of the 104th infantry regiment from 1898 to 1900 and the 3rd battalion of the 117th IR from 1900. From 1902 to 1907, the 2nd Battalion of the 102nd IR was stationed there.[f 4] Two local weekly newspapers contributed to the vibrancy of public life. L'Écho du Loir, established in 1847, espoused conservative and clerical perspectives, whereas Le Journal Fléchois, founded in 1878, adopted a republican, progressive, and secular editorial stance.[a 14]

As was the case in other regions of France, the Belle Époque period saw the emergence of a range of leisure activities in La Flèche, driven in part by the technological advancements of the late 19th century. The first cinematograph arrived in La Flèche in 1897, initiated by the Photographic Society of La Flèche, which organized two screenings. The first color films were shown in 1905 with the arrival of the "Color Cinematograph", which was touring Europe at the time. From November 1907, the Pathé cinematograph permanently settled in the city under the impetus of Louis Paris, who became its exclusive concessionaire.[f 5]

The development of sports is largely attributed to the field of gymnastics. In 1910, the city was home to two sporting societies: the Patriote Fléchoise, a secular society, and the Jeune Garde, which was affiliated with the Gymnastic and Sports Federation of French Patronages.[f 6] Concurrently, the Fléchois Cycling Union (UVF) was established in 1903. Initially, the organization held road races, but the following year saw the construction of a wooden velodrome on Belleborde Street, which proved a significant boon.[f 7][cf 17] The venue hosted regular meetings, which attracted renowned racers such as world champion Major Taylor. However, the UVF ceased to exist in 1910 due to poor financial management and a lack of profitability.[cf 18] The Fléchois Sports Union (USF) was subsequently established with the primary objective of organizing cycling events and foot races. Additionally, it initiated involvement in other sports,[f 7] a strategy also adopted by the Amical Sports Association (ASA), which was founded in 1907. The ASA encouraged athletics and was responsible for the formation of the inaugural Fléchois football team.[f 8] During this period, Fléchois cyclists achieved notable results among professionals, including a 16th-place finish in the 1908 Tour de France.[Note 7] They also played an active role in organizing various sporting events held in La Flèche.[cf 18] With the advent of aviation, the first aviation meeting was held on September 29, 1912, organized by the aviation school of Le Mans and the USF.[f 9]

Following the demise of its last proprietor, Émile Bertron-Auger, a general councilor, the Carmes Castle was placed on the market in 1906.[f 10][Note 8] On September 30, 1907, a property dealer acquired the property with the stipulation that it would be returned to the city of La Flèche should the city express interest. While awaiting the formal acquisition of the castle, the municipal council developed several plans for the utilization of the prospective new premises. Among these was the proposal to establish a public school for girls, which was ultimately rejected by the prefecture. The agreement pertaining to the purchase of the edifice was formally validated by elected officials on March 27, 1909. Thereafter, the decision was taken to transfer the town hall premises from the erstwhile Halle-au-Blé, with this relocation to commence in the following July.[f 10][a 15]

Contemporary era (1914 to present)

[edit]World War I

[edit]On Sunday, August 2, 1914, the day following the issuance of the general mobilization order, numerous residents of Flechoy gathered to witness the departure of the 117th infantry regiment's battalion, which had been stationed at the Gallieni barracks since 1907, by special train.[cf 19] Additionally, René Buquin, who had served as mayor of the commune since 1912, was also mobilized. He temporarily relinquished his duties to Commander André.[f 11] From the outset of the conflict, La Flèche provided shelter to numerous refugees from regions affected by combat operations, predominantly from northern France, the Somme, and Belgium. Some of these individuals were subsequently employed in the city's tanneries. A "Committee for Aid to the Wounded and Needy Franco-Belgian Families" was established to provide assistance to them.[cf 19]

In addition, several hospitals were constructed with the purpose of treating the wounded who were returning from the front. In addition to the hospital, provisional facilities were established at the Notre-Dame College and the Saint-Jacques and Sainte-Jeanne-d'Arc schools, with a collective capacity of nearly 400 beds.[cf 19] The city's barracks served as a temporary accommodation for troops from the 401st infantry regiment; however, La Flèche also functioned as a training center. In 1916, a total of 2,262 men were stationed there from the depots of the 54th, 124th, and 130th infantry regiments, as well as 1,390 soldiers who had been discharged from the classes of 1913 to 1917.[cf 19]

Due to its distance from the front lines, the city was spared direct combat, although food rationing measures were implemented.[cf 19] However, La Flèche suffered a significant loss of life during the conflict, with the deaths of 339 of its soldiers.[44] As was the case with all other French communes, a war memorial was erected in their honor in the years following the Great War. The memorial was inaugurated on May 27, 1923, in the presence of Marshal Foch.[f 12]

Interwar years

[edit]On the morning of March 1, 1919, the Château des Carmes, which served as the town hall, was devastated by a violent fire. The fire was caused by the overheating of a stove used in offices that had been occupied for several weeks by American soldiers. The advanced state of disrepair of the buildings contributed to the rapid spread of flames, which were further exacerbated by the presence of a strong wind, resulting in extensive damage. The estimated cost of the damage was approximately 280,000 gold francs, which was four times the price the city had paid for the building approximately ten years earlier. Following the fire, municipal services were temporarily relocated to the former town hall at the Halle-au-Blé, while the reconstruction of the castle did not commence until 1926 and was completed three years later. The new town hall premises were inaugurated before the end of the reconstruction works in November 1928.[a 16][f 13]

In the postwar period, the city continued to undergo modernization. The installation of a water supply system is completed, and the municipality proceeds with the provision of electricity, with the primary thoroughfares of the city being equipped by early 1923.[a 17] Concurrently, the use of automobiles is on the rise. In 1920, the bridge on the Boulevard de la République was inaugurated, thus becoming the second crossing point of the Loir in the city.[a 6] Conversely, the decline of the railway in La Flèche is documented as early as the 1930s. The Foulletourte-La Flèche tramway line was abolished on December 31, 1932, a mere eighteen years after its commissioning. In 1938, the La Flèche-Aubigné, La Flèche-Sablé, and La Flèche-Angers lines were also terminated.[f 14] Concurrently, the sector of road passenger transport experienced growth with the inauguration of the inaugural regular bus service, which connected to Le Mans in August 1931 and then to Baugé the following November. Over time, this service expanded to link with other major cities in the region, including Angers, Laval, and Tours.[f 15]

From a military standpoint, the decommissioned structures of the Tour d'Auvergne barracks were incorporated into the Prytanée in 1921 to accommodate the growing number of students. In 1944, these structures were renamed "Quartier Gallieni."[e 9]

The construction of the cycling stadium on the Angers road, initiated by Achille Germain at the beginning of 1922, gave a notable boost to both associative and sporting activities.[f 16] Despite the considerable number of events held at the facility, the company responsible for its management encountered financial difficulties, resulting in the closure of the stadium four years after its inauguration. The track was dismantled and relocated to Pontlieue, while the land was sold to private individuals and La Flèche Savings Bank, which constructed housing on the site.[f 17] A new stadium, which later became known as Stade Montréal, was established on land along the Loir at the beginning of 1929.[f 18]

La Flèche under occupation

[edit]On June 17, 1940, the city was subjected to an aerial bombardment by the German military. Approximately forty bombs were dropped by six low-flying aircraft between the La Boirie district and the train station. The bombing resulted in seven fatalities, primarily among military personnel, and caused considerable material destruction. Two days later, the German forces entered La Flèche and proceeded to establish an occupation force, installing the commandant's office in the town hall.[f 19] On June 21, the Luftwaffe established a provisional aerodrome for the transportation of equipment on land situated at the entrance to the city, in close proximity to the Tour d'Auvergne barracks. On the following day, German military personnel from the 615th Artillery Regiment arrived to assume garrison duties in La Flèche, where they remained for a period of eleven months.[f 20] A considerable number of buildings were requisitioned for the accommodation of occupants or the establishment of services. The soldiers' rest home, known as the "Soldatenheim", was established in a building on Grande-Rue, while the offices of the Todt organization, which were headquartered at the Château de Mervé in Luché-Pringé, were set up on Rue Saint-Jacques.[f 21]

In accordance with the German occupation plan, a significant number of French prisoners of war are detained in Germany. Consequently, in April 1942, there were 364 individuals from Fleury-sur-Loire among the prisoners. Moreover, in 1943, the STO, which had been established by the Vichy regime following the failure of the recruitment drive, resulted in the departure of 56 Fléchois to Germany.[f 22] As in other regions of France, the occupation entails the implementation of restrictive measures. Among the refugees who arrived in the city during the exodus of spring 1940 were Jewish families, who were subsequently deported. Among them is the wife of the sculptor Félix-Alexandre Desruelles, who is ultimately saved by the intervention of a notable Fléchois.[f 23][cf 20] A considerable number of Fléchois, whether of their own volition or under duress, were employed by the Germans in the region between 1940 and 1944.[f 24] A significant number of individuals are deployed at the Thorée military camp, which the Germans requisitioned in December 1943 to serve as a storage center for supplies and equipment. Russian prisoners, comprising both male and female individuals, were accommodated in a number of educational facilities within the city, in addition to the former chapel of Notre-Dame-du-Chef-du-Pont. They were subsequently deployed in Luché-Pringé, within the hamlet of Port des Roches, for restoring the departmental road and the establishment of mushroom farms excavated into the tuffeau. These were intended for the storage of ammunition.[45]

The advance of the German army compelled students and teachers to evacuate the Prytanée on May 16, 1940, resulting in a temporary relocation to Billom and subsequently to Valence.[46] In September 1942, the "Petit Prytanée", which encompasses classes from the sixth to the first, was exiled to Briançon. The "Grand Prytanée", which pertains to preparatory classes, returned to its Fléchois premises in October 1943, while the Petit Prytanée remained in Briançon until January 1944.[46]

In the context of the Occupation, the emergence of collaboration in La Flèche is marked by the establishment of a local section of the French Popular Party in 1942, as well as the formation of a branch of the Groupe Collaboration, which had up to sixty members in 1943 and organized a series of conferences. Among the most prominent collaborators in the city, Charles Métayer occupied the roles of district delegate of the Legion of French Volunteers and local chief of the French Militia. In June 1944, the latter's headquarters for the La Flèche district was established at his residence. Concurrently, resistance activity also develops. In response to Chauchet's initiative, small partisan groups are established in La Flèche and its surrounding areas. Their principal objective is to identify potential landing sites for paratroopers and to gather intelligence on the activities of the occupying forces. The information collected is conveyed to Colonel Clouet des Pesruches, proprietor of the Château de Turbilly, who subsequently transmits it to his son, a prominent figure in the Resistance known by the pseudonym Galilée. Raoul Chauchet is apprehended in October 1943, along with several members of the Hercule-Buckmaster network, and deported to Germany.[f 25]

Liberation and Post-War

[edit]On June 7, 1944, the day following the Normandy landings, La Flèche became the target of airstrikes conducted by Allied forces. These attacks occur with great frequency, nearly on a daily basis, and are primarily directed at the station and other transportation infrastructure. The transportation infrastructure is a primary target of the Allied airstrikes. The station is bombed on June 8 and 13, and again on July 4. On the evening of August 7, 1944, two railway workers from La Flèche, Lucien Chartier and André Moguedet, derailed a train in the Mélinais forest, on the La Flèche-Saumur line, which had thus far been spared from bombing. The Germans evacuated La Flèche on the night of August 7-8, setting fire to the supplies they were unable to remove. On August 9, the station was once again bombed by the Allies, while the city was definitively liberated on August 10, 1944, by the American army.[f 26]

The cessation of hostilities in the region is not immediate. On August 11, Lieutenant Paul Favre, an assistant professor at the Prytanée, is killed by German fire during an operation organized by Commander Tête, a doctor at the Prytanée, accompanied by several members of the FFI. The resistance fighters had been warned that the Germans were gathering in a wood located a few kilometers from the village of Thorée-les-Pins to destroy ammunition.[47]

On August 21, 1944, the Fléchois municipal council was dissolved and replaced by a provisional delegation, which assumed responsibility for communal affairs. This provisional delegation, comprising sixteen individuals, convened for the first time three days later and elected Dr. Jean Lhoste, who was then in deportation, as president. The provisional delegation proceeded to oversee the city's governance for a period of eight months, until the municipal elections held in April-May 1945.[g 1]

At the conclusion of the war, numerous cities offered their assistance to municipalities situated in regions that had been impacted by aerial bombardment. Consequently, La Flèche assumed the role of a war sponsor for the small town of Thury-Harcourt in Calvados, which had sustained extensive damage, with 80% of its buildings destroyed. The primary form of assistance provided was the shipment of furniture to residents whose homes had been completely devastated.[48]

The military camp of Thorée-les-Pins, established in 1939 in close proximity to the territory of La Flèche along the road leading to Le Lude, was repurposed on December 9, 1944.[49] The camp was initially designated PWE 22 under the administration of the American military forces and subsequently came under the control of the French army on July 6, 1945, assuming the designation PGA 402. The camp is composed of a set of five secondary camps, including one to four hangars, and is primarily a transit camp where German prisoners stay only a short time. The population of the camp increased to approximately 20,000 detainees at the beginning of 1945, reaching 40,000 prisoners by July of the following year, following the German surrender.[cf 21] The conditions of detention are harsh, and the lack of food leads to a relatively high mortality rate. According to documents maintained in the municipal archives of Thorée-les-Pins, 444 prisoners perished there between July 1945 and August 1946, including 432 deaths from July to November 1945.[cf 21][50]

From the end of the 20th century to the beginning of the 21st century

[edit]

The resurgence of industrial activity in France following the Liberation was not fully reflected in La Flèche until a relatively late point in time. The oldest tanneries and galoshes factories in La Flèche ceased operations in the early 1960s. However, the establishment of industrial zones in the north and south beginning in 1959 facilitated the establishment of new, efficient industries. In 1961, the Kalker industrial rubber company was established, followed by Cebal in 1966, which specialised in the production of metal food packaging, and the Brodard & Taupin printing company in 1967.[40] The establishment of the La Flèche Zoo, created in 1946 by naturalist Jacques Bouillault and which attracted nearly 400,000 visitors in 2018, contributed to the city's tourism development from the late 20th century to the early 21st century.[51] Meanwhile, the city's territorial expansion continued with the annexation of the municipalities of Verron and Saint-Germain-du-Val on January 1, 1965, a century after Sainte-Colombe.[g 2] In addition, several social housing apartment buildings were constructed in various neighborhoods of the city.[52]

In 1961, the municipality of La Flèche procured the 17-hectare Bouchevereau Castle estate, where the Ministry of National Education constructed a school complex comprising multiple facilities. The Bouchevereau school complex was erected in multiple phases over a period of six years and was inaugurated by Minister Edgar Faure on March 3, 1969.[d 7][53]

The cessation of passenger rail services on the La Flèche-Le Mans line in April 1970 signified the conclusion of rail transportation for passengers in La Flèche.[g 3] Nevertheless, in the realm of transportation, the construction of a bypass to the southwest of the city commenced in 1982 with the objective of alleviating traffic congestion in the city center. The construction of the new road necessitated the erection of a third bridge over the Loir, which was entrusted to a group of architects, including Michel Virlogeux, son of the mayor at the time.[40] The bypass was finally inaugurated on December 19, 1985, and was named Avenue Charles-de-Gaulle.[g 4]

The La Flèche area was subjected to a series of flooding incidents during the latter half of the 20th century, with one of the most notable occurring in early January 1961. The Loir reached a height of 2.5 meters on the bridge of the Carmes, and the flood persisted for an entire week, affecting more than 700 residences.[g 5] Two additional notable floods occurred in 1983 and 1984, prompting the authorities to seek external assistance in order to accelerate the implementation of protective measures for various neighborhoods within the municipality.[g 6] In 1989, the riverbed was deepened and its banks were reshaped at the level of the Republic Bridge in order to facilitate more efficient water flow. In 1993, a drainage structure was constructed beneath the former railway line, in close proximity to the level crossing in Balançon.[g 7] However, these works were unable to prevent the city from experiencing three additional significant floods within a relatively short period. In January 1995, the Loir reached a height of 2.40 meters, while it overflowed again in 2000 and 2001, causing considerable damage each time.[g 7] The floods of 1961, 1983, and 1995 brought the Loir to its highest recorded levels in La Flèche.[54]

Towards the conclusion of the 20th century, La Flèche initiated a program of urban renewal and aesthetic enhancement. The municipality initiated a series of substantial urban planning projects, including the expansion of the town hall between 1993 and 1994 by the Adrien Fainsilber firm, the construction of the bus station in 1997, and the renovation In 1999, the Grande Rue was renovated, followed by the renovation of Place Henri-IV the following year. Additionally, a floral campaign was initiated for the city, and a leisure center was developed by Lake Monnerie in 2000.[a 18][g 8] These initiatives persisted into the early 21st century, with the renovation of the facades of St. Thomas Church in 2010 and the restoration work on the Halle-au-Blé in 2012.[a 18] In 2018, the acquisition of a block of unsanitary buildings in the city center permitted the construction of a new cinema, with work extending into 2020.[55]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The initial discovery of a sarcophagus was made in 1939 by the proprietor of Château du Grand-Ruigny in a quarry. Based on her account, a team of archaeologists and historians, including Jean-Louis Destable, undertook an excavation of twelve additional sarcophagi from February 12 to 28, 1990, capitalizing on the construction of Avenue Charles-de-Gaulle. However, the Sarthe General Council and the La Flèche town hall declined to provide funding for an additional archaeological excavation program, and construction of the bypass proceeded.[8]

- ^ The land in question is situated within the boundaries of the Thorée-les-Pins municipality.

- ^ The election of La Flèche then extends over the territory of four current departments: it encompasses all the municipalities in the southwest of Sarthe, along a line from Saint-Denis-d'Orques and Joué-en-Charnie to La Chartre-sur-le-Loir. In addition, the parishes situated to the south of the Loir are included, as are thirteen parishes from Mayenne, extending from Sainte-Suzanne in the north to Saint-Brice in the south. Furthermore, nine parishes from Maine-et-Loire around Durtal and the parish of Chemillé in Indre-et-Loire are incorporated.[16]

- ^ This designation pertains to the existing Place de la Libération.

- ^ The hotel was situated within the structures that currently comprise the Saint-Jacques school.

- ^ Additionally, François-Théodore Latouche, who also served as a general councilor, held the office of mayor from 1852 to 1861.

- ^ At that time, two other amateur cyclists from La Flèche participated in the Tour de France. Albert Leroy was the first to participate in the Tour de France in 1904, while Alfred Vaidis, who was competing as an individual, placed 29th in the 1909 Tour de France.[41][42]

- ^ The Château des Carmes was sold as national property during the French Revolution and subsequently purchased in 1796 by François-René Bertron, the son of a peasant from the neighboring commune of Fougeré. Throughout the nineteenth century, his heirs amassed considerable wealth through textile trading, which enabled them to undertake numerous beautification projects for the castle. Upon the death of Émile Bertron-Auger, the castle's last occupant, in 1906, his heirs promptly initiated the liquidation of his assets.[43]

References

[edit]- Cahiers Fléchois

- ^ a b Destable, Jean-Louis (1982). "Recherches archéologiques en pays fléchois" [Archaeological research in the Fléchois region]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (4): 3–9.

- ^ a b c d e Destable, Jean-Louis (1979). "Éléments pouvant servir à l'histoire des origines de La Flèche et du pays fléchois" [Elements of interest in the history of the origins of La Flèche and the Fléchois region]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (1): 8–13.

- ^ Destable, Jean-Louis (1991). "La nécropole haut-médiévale du Grand-Ruigné à La Flèche" [The early medieval necropolis of Grand-Ruigné in La Flèche]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (12): 3–8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Schilte, Pierre (2002). "Notre-Dame du chef du pont, vestiges de la chapelle, métamorphoses de la statue" [Notre-Dame du chef du pont, remains of the chapel, metamorphoses of the statue]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (23): 64–77.

- ^ Lesur, Jean-Marc (2007). "Jean de Beaugency, premier seigneur de La Flèche : Esquisse de synthèse de nos connaissances" [Jean de Beaugency, first lord of La Flèche: Sketch of a synthesis of our knowledge]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (28): 31–36.

- ^ a b Lesur, Jean-Marc (2009). "La vie religieuse à La Flèche au Moyen-Âge" [Religious life in La Flèche in the Middle Ages]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (30): 5–10.

- ^ a b Schilte, Pierre (1979). "Le Château-Neuf de Françoise d'Alençon" [Françoise d'Alençon's Château-Neuf]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (1): 27–29.

- ^ de Dieuleveult, Alain (2016). "Une tradition dénoncée : la conception d'Henri IV" [A denounced tradition: the conception of Henri IV]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (37): 1–2.

- ^ a b c d e de Dieuleveult, Alain (2009). "Comment vivaient les Fléchois aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles" [How the people of Fléch lived in the 17th and 18th centuries]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (37): 13–58.

- ^ Termeau, Jacques (1988). "La population de La Flèche au XVIIe siècle" [The population of La Flèche in the 17th century]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (9): 13–22.

- ^ a b Rouleau, Robert (2003). "La formation de la « Grande Recrue » pour Montréal" [Training the “Grande Recrue” for Montreal]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (24): 51–70.

- ^ Schilte, Pierre (1979). "Le cloître de l'hôpital" [The hospital cloister]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (1): 30–33.

- ^ a b c de Dieuleveult, Alain (2017). "Menaces contre le Prytanée au XIXe siècle" [Threats to the Prytanée in the 19th century]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (38): 75–90.

- ^ de Dieuleveult, Alain (1982). "La guillotine de La Flèche" [The guillotine at La Flèche]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (4): 26–35.

- ^ Planson, Cyrille (2014). "Jean Châtelain dit général Tranquille, le chouan du Pays Fléchois" [Jean Châtelain, known as General Tranquille, the Chouan of the Pays Fléchois]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (35): 49–58.

- ^ "Mille ans d'histoire fléchoise en raccourci" [A thousand years of Fléchoise history in a nutshell]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (31): I–III. 2010.

- ^ Potron, Daniel (1982). "Le stade vélodrome fléchois" [The Fléchois velodrome stadium]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (4): 56–69.

- ^ a b Weecxsteen, Pierre (1991). "On l'appelait Germain de La Flèche" [They called him Germain de La Flèche]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (12): 101–144.

- ^ a b c d e Termeau, Jacques (1979). "Souvenirs et notes sur La Flèche pendant la Grande Guerre" [Recollections and notes on La Flèche during the Great War]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (1): 70–74.

- ^ Potron, Daniel (1991). "Un sculpteur parmi les réfugiés fléchois de la dernière guerre" [A sculptor among the Fléchois refugees of the last war]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (12): 145–149.

- ^ a b Potron, Daniel (1998). "Le « Camp de le faim » de Thorée" [The “Hunger Camp” at Thorée]. Cahiers Fléchois (in French) (19): 165–199.

- Alain de Dieuleveult et Michelle Sadoulet, Quatre siècles de municipalités pour La Flèche : 1615-2015, 2015.

- ^ a b de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 13

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 15

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 17

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, pp. 17–19

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 19

- ^ a b de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 23

- ^ a b de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 28

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, pp. 169–171

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, pp. 59–62

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, pp. 117–119

- ^ a b c de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, pp. 121–122

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 62

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, pp. 73–76

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 106

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, pp. 64–66

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 68

- ^ de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 138

- ^ a b de Dieuleveult & Sadoulet 2015, p. 151

- Charles de Montzey, Histoire de La Flèche et de ses seigneurs, 1877-1878.

- ^ Montzey 1878, p. 39, Vol. I

- ^ Montzey 1878, p. 13, Vol. I

- ^ Montzey 1878, pp. 35–37, Vol. I

- ^ Montzey 1878, p. 14, Vol. I

- ^ Montzey 1878, pp. 103–111, Vol. I