Arisaid

An arisaid[1][2][3] (Scottish Gaelic: earasaid[4] or arasaid[4]) is a draped garment historically worn in Scotland in the 17th and 18th century (and probably earlier) as part of traditional female Highland dress. It was worn as a dress – a long, feminine version of the masculine belted plaid – or as an unbelted wrap. An earasaid might be brightly coloured[5] or made of lachdann (dun or undyed) wool.[6] Some colours were more expensive than others.[2] The garment might be single-coloured, striped,[6] or tartan[5] – especially of black, blue, and red stripes on white.[1] White-based earasaid tartans influenced later dance and sometimes dress tartans, as well as household-item tartans in a style called "barred blanket" tartan.

Overview

[edit]In cut, it was a large rectangle, longer than the wearer was tall, and wider than the wearer's waist circumference. The bottom edge was ankle length and the top edge, when not being used as a hood, might hang cape-like behind. The width might be pleated until it wrapped around the waist, and the pleats held under a belt. In this case, the cloth below the belt hung like a skirt; the cloth above the belt might be pinned or pulled over the head. The plaid could also be worn unbelted; and it seems it was also later worn at waist-width .

Near the beginning of the 18th century, Martin Martin gave a description of traditional women's clothing (i.e. dating at least well into the 17th century) in the Western Islands, including the earasaid and its brooches and buckles.[7]

The ancient dress wore by the women, and which is yet wore by some of the vulgar, called arisad, is a white plaid, having a few small stripes of black, blue and red; it reached from the neck to the heels, and was tied before on the breast with a buckle of silver or brass, according to the quality of the person. I have seen some of the former of an hundred marks value; it was broad as any ordinary pewter plate, the whole curiously engraven with various animals etc. There was a lesser buckle which was wore in the middle of the larger, and above two ounces weight; it had in the centre a large piece of crystal, or some finer stone, and this was set all around with several finer stones of a lesser size. The plaid being pleated all round, was tied with a belt below the breast; the belt was of leather, and several pieces of silver intermixed with the leather like a chain. The lower end of the belt has a piece of plate about eight inches long, and three in breadth, curiously engraven; the end of which was adorned with fine stones, or pieces of red coral. They wore sleeves of scarlet cloth, closed at the end as men's vests, with gold lace round them, having plate buttons with fine stones. The head dress was a fine kerchief of linen strait (tight) about the head, hanging down the back taper-wise; a large lock of hair hangs down their cheeks above their breast, the lower end tied with a knot of ribbands.

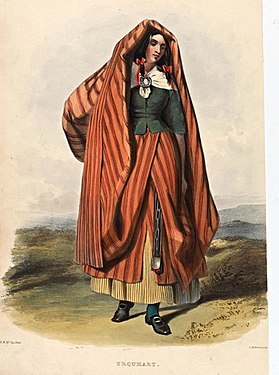

The 1845 illustration is a reconstruction based on this description, then a century and a half old. Somewhat older drawings from life do not show details of the garment:[2]

-

Scottish officer's wife in Flanders, 1743, in an ankle-length unbelted arisaid, pinned with a small fastening at the throat, worn over a bodice and possibly a skirt, with a headcloth and bonnet

-

Highland soldier's family, 1754; the woman wears a belted arisaid, apparently bloused and pinned on one shoulder, and she also appears to have tailored sleeves.

-

"Urquhart", by R. R. McIan, from James Logan's The Clans of the Scottish Highlands, 1845; this reconstruction is from a written description of ~150 years earlier

-

"Sinclair", another reconstruction from The Clans of the Scottish Highlands, 1845

Descriptions of women's plaids

[edit]

One early (early 19th century) dictionary definition of earasaid describes it, in the past tense, as full-length and worn without underclothing.[2] Martin Martin describes it a full-length and worn over a sleeved top. Later descriptions (notably Burt) use the word plaid to describe, at first, wraps that cover the whole body, and then garments that cover only from head to waist. Poorer people are described as wearing full-length blankets.

The Ladies dress as in England, with this Difference, that when they go abroad, from the highest to the loweft, they wear a Plaid, which cover Half of the Face, and all their Body. In Spain, Flanders, and Holland, you know the Women go all to Church and Market, with a black Mantle over their Heads and Body: But these in Scotland are all strip'd with Green, Scarlet, and other Colours, and most of them lin'd with Silk ; which in the Middle of a Church, on a Sunday, looks like a Parterre de Fleurs.

— John Macky, A Journey through Scotland, written 1722, published 1729[8]

The Minister here in Scotland would have the Ladies come to Kirk in their Plaids, which hide any loose Dress, and their Faces, too, if they would be persuaded, in order to prevent the wandering Thoughts of young Fellows, and perhaps some young old ones too; for the Minister looks upon a well-dressed Woman to be an Object unfit to be seen in the Time of Divine Service, especially if she be handsome.

The before-mentioned Writer of a "Journey through Scotland," has borrowed a Thought from the Tatler or Spectator, I do not remember which of them.

Speaking of the Ladies' Plaids, he says — "They are striped with Green, Scarlet, and other Colours, which, in the Middle of a Church on a Sunday, look like a Parterre de Fleurs.'" Instead of striped he should have said chequered, but that would not so well agree with his Flowers ; and I must ask Leave to differ from him in the Simile, for at first I thought it a very odd sight ; and as to outward Appearance, more fit to be compared with an Assembly of Harlequins than a Bed of Tulips.

The Plaid is the Undress of the Ladies; and to a genteel Woman, who adjusts it with a good Air, it is a becoming Veil. But as I am pretty sure you never saw one of them in England, I shall employ a few Words to describe it to you. It is made of Silk or fine Worsted, chequered with various lively colours, two Breadths wide, and three Yards in Length; it is brought over the Head, and may hide or discover the Face according to the Wearer's Fancy or Occasion; it reaches to the Waist behind; one corner falls as low as the Ankle on one side; and the other Part, in Folds, hangs down from the opposite arm.

— Burt's Letters from the North of Scotland, 1754[9]

Some of these [peat] Carts are led by Women, who are generally bare-foot, with a Blanket for the covering of their Bodies, and in cold or wet Weather they bring it quite over them. At other times they wear a Piece of Linen upon their Heads, made up like a Napkin-Cap in an inn, only not tied at top, but hanging down behind....

When they [female servants] go Abroad, they wear a Blanket over their Heads, as the poor Women do, something like the Pictures you may have seen of some bare-footed Order among the Romish Priests.

And the same Blanket that serves them for a Mantle by day, is made a Part of their bedding at Night, which is generally generally spread upon the floor; this, I think, they call a Shakedown.

— Burt's Letters from the North of Scotland, 1754[9]

The women's dress is the kirch, or a white piece of linnen, pinned over the foreheads of thofe that are married, and round the hind part of the head, falling behind over their necks. The single women wear only a ribband round their head, which they call a snood. The tanac or plaid, hangs over their shoulders, and is fastened before with a brotche; but in bad weather is drawn over their heads: I have also observed during divine service, that they keep drawing it forward in proportion as their attention increases; insomuch as to conceal at last: their whole face, as if it was to exclude every external object that might interrupt their devotion. In the county of Breadalbane, many wear, when in high dress, a great pleated stocking of an enormous length, called offan. In other respects, their dress resembles that of women of the same rank in England.

— Thomas Pennant, A Tour in Scotland, 1769[10]

Historical example

[edit]Christina Young spun, dyed, and wove a surviving tartan plaid; it has the year "1726" and the maker's initials stitched into the edge;[11] it dates from before Highland dress was banned (though the ban did not apply to women, anyway). A reconstruction in the Scottish Tartans Museum is displayed worn as an earasaid, although there is some doubt as to whether this is accurate.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Banks, Jeffrey; de la Chapelle, Doria (2007). Tartan: Romancing the Plaid. New York: Rizzoli. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8478-2982-8.

- ^ a b c d e MacDonald, Peter Eslea (2016). "Musings on the Arisaid and other female dress" (PDF). ScottishTartans.co.uk.

- ^ Tuckett, Sally (2016). "Reassessing the romance: Tartan as a popular commodity, c.1770–1830" (PDF). Scottish Historical Review. 95 (2): 3. doi:10.3366/shr.2016.0295.

- ^ a b "Earasaid Archived 2016-04-13 at the Wayback Machine" at Dwelly's Gaelic Dictionary

- ^ a b "The usual habit of both sexes is the pladd; the women's much finer, the colours more lively, and the square much larger than the men's, and put me in the mind of the ancient Picts. This serves them for a veil and covers both head and body." William Sachceverell, of the Isle of Mull, in 1688; quoted in A chronological list of tartan-related source texts

- ^ a b "Women's Dress". TartansAuthority.com. Scottish Tartans Authority. 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2023. Quoting: Logan, James; MacIan, Robert Ronald (1845–47). Clans of the Scottish Highlands. London: Ackermann & Co.

The arisaid was usually of lachdan, or of a saffron hue, but it was also striped, with various colours according to taste.

- ^ Martin, Description of the Western Islands of Scotland, (1703), pp. 208–209: quoted in Robertson, ed., Inventaires de la Royne Desscosse, Bannatyne Club, (1863) p. lxviii footnote.

- ^ "John Macky (Macky, John, -1726) - The Online Books Page". OnlineBooks.Library.UPenn.edu. University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ a b Burt, Edward (29 June 1876). "Burt's letters from the north of Scotland; with facsimiles of the original engravings". Edinburgh : W. Paterson – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Pennant, Thomas (29 June 1772). "A tour in Scotland, 1769". London : Printed for B. White at Horace's Head – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Tartan Details". Scottish Register of Tartans. National Records of Scotland.