Rhodesia Information Centre

| Rhodesia Information Centre | |

|---|---|

The Rhodesia Information Centre's office in December 1972 | |

| Location | 9 Myrtle Street, Crows Nest, New South Wales[1] |

| Opened | 1966 (as the Rhodesian Information Service) |

| Closed | 1980 (as the Zimbabwe Information Centre) |

| Jurisdiction | Unaccredited representative office of Rhodesia in Australia, including propaganda functions |

The Rhodesia Information Centre (RIC), also known as the Rhodesian Information Centre,[2] the Rhodesia Information Service,[3] the Flame Lily Centre and the Zimbabwe Information Centre, represented the Rhodesian government in Australia from 1966 to 1980. As Australia did not recognise Rhodesia's independence, it operated on an unofficial basis.

Rhodesia's quasi-diplomatic presence in Australia was initially established in Melbourne during 1966 as the Rhodesian Information Service. This organisation closed the next year, and was replaced with the RIC in Sydney. The centre's activities included lobbying politicians, spreading propaganda supporting white minority rule in Rhodesia and advising Australian businesses on how they could evade the United Nations sanctions that had been imposed on the country. It collaborated with a far-right organisation and a pro-Rhodesia community organisation. These activities, and the centre's presence in Australia, violated United Nations Security Council resolutions, including some that specifically targeted it and the other Rhodesian diplomatic posts. The RIC had little impact, with Australian media coverage of the Rhodesian regime being almost entirely negative and the government's opposition to white minority rule in Rhodesia hardening over time.

While the centre was initially tolerated by the Australian government, its operations became controversial from the early 1970s. The RIC's role in disseminating propaganda was revealed in March 1972, but the government of the day chose to not take any substantive action in response. The Whitlam government that was in power from late 1972 to November 1975 unsuccessfully attempted to force the centre to close on several occasions, with the High Court ruling one of the attempts to have been illegal. In 1977 the Fraser government also attempted to close the RIC, but backed down in the face of a backbench revolt over the issue. The Zimbabwean government shut the centre in May 1980 after the end of white minority rule and later established an official embassy in Australia.

Background

[edit]Rhodesian independence

[edit]Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British colony in Africa which was dominated by the small white minority. In 1964, the population comprised approximately 220,000 Europeans and four million Africans. The black majority was largely excluded from power; for instance, 50 of the 65 seats in the parliament's lower house were reserved for whites. On 11 November 1965 the Southern Rhodesian government led by Prime Minister Ian Smith issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (commonly referred to as UDI) that was illegal under British law, with the colony becoming Rhodesia. The Rhodesian government's decision to declare independence sought to maintain white rule, with the ruling Rhodesian Front party opposing a transition to majority rule as had recently happened in the neighbouring British colonies of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland.[4] The British government did not recognise Rhodesia's independence, and the United Nations Security Council urged United Nations member countries to not recognise the Rhodesian regime or provide it with any assistance. The United Nations encouraged voluntary trade sanctions against Rhodesia from November 1965, and these began to become mandatory from December 1966.[5] No country ever formally recognised Rhodesia as an independent state, with all regarding UDI as illegal.[6]

The lack of international recognition greatly constrained Rhodesia's ability to operate diplomatic missions in other countries.[6] Only the South African and Portuguese governments were willing to permit Rhodesian diplomats to be stationed in their country.[7] Rhodesian diplomatic missions were maintained in Lisbon, Lourenço Marques in Mozambique, Cape Town and Pretoria.[8] The Rhodesian High Commission in London that had preceded UDI operated until 1969.[9] The British government required the High Commission to limit its activities to providing consular assistance for Rhodesians in the United Kingdom, and banned it from public relations activities as well as promoting trade and migration.[10] The Rhodesian High Commission in Rhodesia House was directed to close by the British government following the 1969 Rhodesian constitutional referendum, in which white Rhodesians endorsed a proposal for the country to become a republic after the Rhodesian attempt to recognise Queen Elizabeth II as a separate Rhodesian monarch was not recognised internationally.[11] A Rhodesian Information Office was established in Washington, D.C., following UDI and another opened in Paris during 1968; neither was recognised as a diplomatic mission by the host country and the office in Paris was limited to promoting tourism and cultural exchanges.[12] Small Rhodesian representative offices operated semi-clandestinely at various times in Athens, Brussels, Kinshasa, Libreville, Madrid, Munich and Rome; the governments of these countries were aware of the offices but did not formally recognise them.[8][13]

Australian response to UDI

[edit]

The Australian government never recognised Rhodesia's independence and opposed white minority rule in the country, but was initially reluctant to take concrete steps against the regime.[14][15] This reluctance was motivated by support for the white Rhodesian cause among sections of the Australian population. Many Australians felt that the white Rhodesians were 'kith and kin' and were not concerned about the Rhodesian government's racist policies. It took lobbying from the British government for the Australian government to impose trade sanctions on Rhodesia in December 1965. The Australian Trade Commission in the Rhodesian capital of Salisbury was also closed.[16] In line with its view that the Rhodesian government had no legal standing, the Australian government refused to deal directly with it. Messages received from the Rhodesian government did not receive a response.[17]

Despite its overall stance against Rhodesia, the Liberal Party of Australia-Country Party coalition government that was in power at the federal level in Australia until December 1972 provided some diplomatic support for the regime. This included issuing Australian passports to the secretary of the Rhodesian Ministry of External Affairs and the Rhodesian representatives to South Africa and Portugal (all three men were Australian citizens) and abstaining from several United Nations General Assembly resolutions that called for strong action to be taken against Rhodesia.[18][19][20] Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s the Australian government remained unenthusiastic about further extensions to the trade sanctions and was not active in the Commonwealth's efforts to find a solution to the Rhodesian problem.[21] Enforcement of trade sanctions was also uneven, and was undertaken through regulations rather than stricter measures such as legislation.[22] While imports from Rhodesia to Australia ceased, the quantity of Australian goods exported to Rhodesia increased between 1965 and 1973.[23] In 1970 the Australian government defended the export of wheat to Rhodesia on humanitarian grounds. It claimed that the wheat was needed by Rhodesia's black population, despite their staple food being maize.[24][25]

Establishment and role

[edit]The Rhodesian government did not have a diplomatic presence in Australia prior to UDI.[26] In 1966 it established the Rhodesian Information Service in Melbourne.[27] The service's first director was T.A. Cresswell-George, an Australian citizen.[27][28] An information office was also opened in Sydney as a branch of the Rhodesian Information Service.[29]

The Rhodesian Information Service in Melbourne was closed in 1967, and replaced with the Rhodesian Information Centre (RIC) in Sydney. The centre was led by Keith Chalmers, a former Rhodesian diplomat.[27][30] Chalmers had arrived in Australia in 1967 and was granted Australian citizenship in July 1969.[31] The RIC was registered as a business in New South Wales, with the state government being aware from the outset that it was operated by the Rhodesian government.[18][30]

The director of the centre, Denzil Bradley, claimed in 1972 that its role was to disseminate "factual information about Rhodesia throughout Australia".[1] In reality, the RIC was a de facto diplomatic mission that represented the Rhodesian government in Australia.[23][32][33] This made it the Rhodesian government's main way of engaging with Australians.[34] The information the centre provided was mainly propaganda for the Rhodesian regime.[1][30][35] It lobbied members of the federal and state parliaments and advised Australian businesses about how they could evade the sanctions that had been placed on the country.[30][36] It also handled queries about visas and migration to Rhodesia.[32] The Zimbabwe African National Union, one of the main forces fighting white rule within Rhodesia, alleged in 1978 that the RIC had recruited Australians to fight with the Rhodesian Security Forces. This was denied by the centre's director.[37] The RIC had previously stated in 1977 that Australians who contacted it about enlisting in the Rhodesian Security Forces were told to communicate directly with the relevant organisation in Rhodesia.[38]

Documents stolen from the centre in 1972 indicated that most of its funding came from the Rhodesian Ministry of Information via a Swiss bank account. At this time its director was a Rhodesian who had taken out Australian citizenship, the deputy director was South African and it had one other full-time staff member and an unspecified number of casual employees.[30] Greg Aplin, the director of the RIC from 1977 to 1980, stated in his inaugural speech after being elected to the New South Wales Parliament in 2003, that he had been a diplomat with the Rhodesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and was seconded to an information role during his posting to Sydney.[39]

One of the RIC's roles was distributing a periodical entitled The Rhodesian Commentary in Australia and New Zealand. This largely comprised material written in Rhodesia which was favourable to the Rhodesian government.[27][40] All editions also included a page on the activities of the Rhodesia-Australia Association's branches in each Australian state. One issue of The Rhodesian Commentary claimed that it had a mailing list of 5,500, but this likely included libraries, politicians and other recipients who were sent unsolicited copies.[40]

The Rhodesian Information Centre's activities were illegal. They violated several United Nations Security Council resolutions that banned the Rhodesian regime from engaging in diplomatic activity, as well as regulations made under Australian customs law that prohibited the importation of materials from Rhodesia.[41]

Writing in 1972, the commentator and then-opposition Australian Labor Party staffer Richard V. Hall judged that the centre's attempts to influence Australian politicians and journalists had been "extensive but inept", with media coverage of the Rhodesian regime in Australia being almost entirely negative.[42] A 1977 editorial in The Canberra Times stated that the RIC was "relatively innocuous and mostly ineffective".[43]

Australian responses

[edit]1966 to 1972

[edit]The Liberal Party of Australia-Country Party coalition government tolerated the RIC. This formed part of the limited diplomatic support it provided to the Rhodesian government.[18][19] The centre attracted little controversy in Australia in its first years of operations.[27]

In late 1966 Cresswell-George wrote to the Australian Minister for Trade and Industry John McEwen to propose that the government invite a delegation of Rhodesian officials to Australia for trade talks. In his reply, McEwen agreed for Cresswell-George to meet with staff from the Department of Trade and Industry to discuss the proposal. The Department of Foreign Affairs told the Department of Trade and Industry in late November that such a meeting would violate government policy against contact with the Rhodesian regime and could embarrass the government. It recommended that the department write to Cresswell-George declining the meeting.[27] The Department of Trade and Industry believed that McEwen's letter had committed it to meet with Cresswell-George, and the latter visited the department's offices on 2 December 1966. The Department of Trade and Industry officers who met with Cresswell-George stressed that they did not accept his claim to represent Rhodesia and that the Australian government was not considering recognising the country. Cresswell-George explained the goals and composition of the proposed delegation, which was to have included a senior government officer and two business people. In response, the Australian officers indicated that while Rhodesian business people could visit Australia individually or as a group to investigate future trade opportunities, the government would not recognise them as an official delegation or provide any forms of assistance.[44]

The federal and New South Wales governments' tolerance of the RIC was not in accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 277, which was adopted in 1970 and called on UN member states to "ensure that any act performed by officials and institutions of the illegal regime in Southern Rhodesia shall not be accorded any recognition, official or otherwise, including judicial notice, by the competent organs of their State".[45] By the early 1970s the Department of Foreign Affairs was encouraging the government to more strongly enforce sanctions against Rhodesia. The department favoured taking steps to close the RIC, but did not pursue this as the Attorney-General's Department opposed doing so.[46] In April 1971 the United Nations Sanctions Committee raised concerns with the Australian government that the RIC could be in breach of Security Council Resolution 253, and sought information about it. This resolution had been enacted in May 1968, and tightened the restrictions on trade and government to government contact with Rhodesia. The Australian government's response in May 1971 noted that the RIC had been established before Security Council Resolution 253 was adopted. It was also stated that "so far as the Australian Government is concerned, the centre is a private office and neither the office not its personnel have any official status whatsoever", and the government did "not correspond with the office or acknowledge any correspondence from it". The United Nations Sanctions Committee did not take any further steps.[47]

Public disclosure of the RIC's role

[edit]

In March 1972, a small group known as the Alternate Rhodesia Information Centre, which was led by the Rhodesian-born activist against the regime, Sekai Holland, passed on documents that had been stolen from the RIC to the Australian media. These documents appeared to show that the centre was operating as a de facto embassy and advising businesses about how to evade sanctions.[23] For instance, the documents showed that the Rhodesian government referred to it as a "mission", using the same terminology as it applied to the overt diplomatic posts in Portugal and South Africa. Other documents provided examples of how the RIC was attempting to influence politicians and journalists, including by offering free trips to Rhodesia, and indicated extensive collaboration with the far-right Australian League of Rights.[42] The documents also demonstrated that the South African Embassy in Canberra had violated customs regulations by importing Rhodesian films and propaganda on behalf of the centre.[48] The Age and The Review published several stories about these revelations.[48][32] The director of the RIC "emphatically denied" that it had smuggled publicity material into Australia or been involved in intelligence-gathering activities.[49] The South African Ambassador, John Mills, also issued a statement denying that his staff had done anything improper.[50]

In response to the media coverage, the Australian government directed the Department of Foreign Affairs to investigate the possible violation of customs regulations.[18] Customs officers also raided the centre.[45] The Department of Foreign Affairs and the Department of Customs and Excise found that the material stolen from the RIC demonstrated that it was run by the Rhodesian government.[46] The Department of Foreign Affairs recommended that the centre be closed, but the government decided to not take any action. The Minister for Foreign Affairs Nigel Bowen stated on 11 April 1972 that the government did not have the legal authority to close the centre.[51] Richard V. Hall attributed this decision to the influence of the "Rhodesia Lobby"[45] and an editorial in The Age stated that the government's lack of action "showed clearly – all too clearly – where its sympathies lay".[52] During a parliamentary debate on racism and violence in May 1972 the federal opposition leader Gough Whitlam criticised the government for not closing the centre.[53]

Minister for Customs and Excise Don Chipp believed that the affair was the result of overly strict regulations on importing works from Rhodesia as he considered some of the material found to have violated the ban to be inoffensive. He gained the Cabinet's agreement for the regulations to be reviewed so that they would be enforced "with common sense" in the future.[54] The Department of Foreign Affairs was unhappy with this outcome, as it believed that relaxing the regulations would reinforce the international perception that Australia was not serious about enforcing sanctions against Rhodesia. Bowen concurred, and told Chipp that easing the regulations would help the Rhodesian regime disseminate propaganda in Australia.[55] In July 1972 the government announced that it would not renew the Australian passports that had been issued to the head of the Rhodesian Ministry of External Affairs and the Rhodesian representatives in Portugal and South Africa on the grounds that they were working for a government that Australia did not recognise.[56][57]

As part of a collection of official documents published in 2017, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade historian Matthew Jordan stated that the government's failure to act against the Rhodesia Information Centre in 1972 after its illegal activities had been revealed demonstrated its "residual sympathy" for the white Rhodesians. He also judged that Chipp's response to the revelations "was symptomatic of the Australian Government's half-hearted commitment to the long-term objective of overturning the white minority regime in Salisbury".[58]

Whitlam government

[edit]Business name deregistration

[edit]The Australian Labor Party Whitlam government was determined to take a strong stance against Rhodesia. Its priorities included strongly enforcing the United Nations sanctions, banning visits by Rhodesian sports teams that had been racially selected and closing the RIC.[23] The Alternate Rhodesia Information Centre was prominent in pressuring the Whitlam government to take action against the RIC, and developed links with groups representing university students including the leaders of the National Union of Students.[23]

Whitlam wrote to the Liberal Party Premier of New South Wales Robert Askin on 7 December 1972 to request that the RIC's business name be deregistered.[59][60] As part of its efforts to destabilise the Askin Government, the Whitlam government leaked this correspondence to the media. Askin was offended by the leak and argued that he did not need to act on Whitlam's request.[61] Nevertheless, in March 1973 his government lodged an application with the Supreme Court of New South Wales seeking permission to cancel the centre's business name.[62][63] This application was granted in June 1973, with the court finding that the Attorney-General of New South Wales' consent was needed to register an organisation of that name given that it implied a connection with the Rhodesian government. As part of this case the Whitlam government provided a certificate confirming that it did not recognise the Rhodesian government or people who claimed to represent it.[64] The RIC lodged an appeal, in part on the basis that a reasonable person would not believe that its name indicated that it was linked to the Rhodesian government. The New South Wales Court of Appeal upheld the Supreme Court's decision in June 1974.[65][66] Following this ruling the centre was re-registered as the Flame Lily Centre (named after the Rhodesian national flower) and continued to operate as the Rhodesia Information Centre.[67]

A group of Australians led by Sekai Holland applied to the New South Wales Registrar of Business Names in December 1972 seeking to register another body to be called the Rhodesia Information Centre that would represent the black majority in Rhodesia.[68] This application was rejected.[69] In March 1973 Holland said that she had proof that the RIC maintained dossiers on Rhodesians in Australia.[70] The Alternate Rhodesia Information Centre was renamed the Free Zimbabwe Centre by August 1973.[71]

High Court case

[edit]On 18 April 1973, Postmaster-General Lionel Bowen instructed the Postmaster-General's Department to cease all mail, telephone and telegram services to the centre, including by locking their post office box and deregistering The Rhodesian Commentary as a newspaper.[35][72] Denzil Bradley initiated legal action in response, and Bowen's directive was overturned by the High Court of Australia on 10 September 1973 in the case Bradley v Commonwealth.[1] The High Court found that Bowen had exceeded his powers under the Post and Telegraph Act and its regulations, and ordered that the government pay the RIC's legal costs.[73]

During this period the centre's office at Crows Nest was petrol bombed on 7 July 1973. The furniture and fittings were badly damaged.[74] In August 1973 Sekai Holland and six other members of the Free Zimbabwe Centre were arrested after they occupied the RIC's offices in protest against its continuing operations.[71]

Whitlam stated in September 1973 that the government would consider amending the Post and Telegraphs Act to allow the Postmaster-General to withdraw services to the RIC.[75] He also claimed in November 1973, ahead of the 1973 New South Wales state election, that Askin supported the Rhodesian regime and had failed to cooperate with efforts to close the centre. Askin rejected this claim, noting that his government had cancelled the RIC's business name and lacked the legal authority to close the centre.[62]

The Australian Labor Party Caucus approved draft legislation on 6 March 1974 to close the RIC.[76] This legislation was not introduced into Parliament, however, due to competing priorities and frequent disruptions to the parliamentary schedule.[77] The government attempted to remove the centre's listing from Sydney telephone directories in December 1974, but a High Court justice issued an injunction prohibiting this action in February 1975.[78] The full bench of the High Court considered the matter in August 1975. It endorsed a consent order proposing that the case not proceed after being told that the RIC's details had been included in the 1975 directory and would also appear in a 1975–76 directory. The government was ordered to pay the centre's costs.[79] The RIC's office was petrol bombed again in March 1975. Approximately $1,500 worth of damage was caused in this incident.[80]

The Rhodesian diplomatic presence was reduced during the mid-1970s. A Rhodesian tourist office in New York City was forced to close by the United States government during 1974. In 1975 the formal Rhodesian diplomatic missions in Portugal and Mozambique were also required to close by the host governments.[7]

Fraser government

[edit]

Further attempts to close the RIC

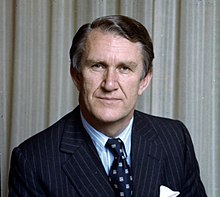

[edit]Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, who headed the Liberal-National Country Party coalition Fraser government that replaced the Whitlam government in November 1975, had a strong commitment to racial equality.[81] He believed that action against the white minority governments in Rhodesia and South Africa should be a priority for his government's foreign policies on both ethical and geopolitical grounds. Opinion within the coalition government's elected members was split on this issue, with some openly supporting the continuation of white minority rule in Rhodesia.[82]

Further steps were taken internationally during 1977 to disrupt Rhodesia's diplomatic activities. The French government forced the Rhodesian Information Office in Paris to close in January 1977.[8] On 27 May 1977, the United Nations Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 409 whose provisions banned the transfer of funds from the Rhodesian government to offices or agents operating on its behalf in other countries. This aimed to hinder the Rhodesian information offices in Australia, South Africa and the United States.[83][84] The Carter Administration took steps to cut off funding from Rhodesia to the Rhodesian Information Office in Washington, D.C., in line with this resolution during August 1977, but it remained open until 1979 after receiving donations from American citizens.[85]

Fraser and his cabinet believed that they needed to comply with Resolution 409 and force the RIC to close. It was thought that Australia would become diplomatically isolated if the centre was allowed to remain open, and Fraser's advocacy at Commonwealth meetings would be compromised. In making the decision to close the centre, the Cabinet noted that doing so would impose some constraints on freedom of expression.[86] Andrew Peacock, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, announced in Parliament on 24 May 1977 that the government was considering legislating to enforce Resolution 409 if it was adopted. On 6 June the Australian government formally notified the United Nations via a letter to the Secretary-General that it intended "to introduce legislation designed to give effect to the most recent resolution directed against the maintenance of Rhodesian information offices and agencies abroad".[87]

The RIC Centre lobbied the public and government backbenchers to prevent its closure. Roy van der Spuy, the centre's director, argued that Australia was not bound to enforce United Nations resolutions, that the High Court had upheld the centre's legality and that closing the centre would violate the principle of freedom of speech. He noted that the Liberal Party's platform included commitments to protect individual liberties and freedom of speech.[87]

The closure of the RIC was strongly opposed by many government backbenchers when parliament resumed on 17 August 1977.[87] Some were motivated by sympathy for Rhodesia, but a larger number believed that closing the centre would be an unjustifiable violation of civil liberties.[86] A large proportion of the non-elected members of the National Country Party and the New South Wales branch of the Liberal Party also opposed the legislation, which put further pressure on the elected members.[88] The Sydney Morning Herald reported on 18 August that "30 to 50 per cent" of government members of parliament opposed the legislation, with at least twelve being prepared to cross the floor and vote against it.[89] For instance, the Member for Tangney Peter Richardson argued that closing the centre would violate freedom of speech and give the United Nations excessive influence over Australian domestic policies. He also stated that the Rhodesian government was "less menacing to our national interests than Soviet Russia and China".[90] Richardson's decision in September 1977 to leave politics was, in part, a protest against Fraser's stance towards the RIC.[91] At the end of September The National Times reported that 40 of the 126 government members of parliament and senators were opposed to legislating to close the centre.[92][93]

On 20 September, Peacock gave a commitment in Parliament any legislation introduced to close the RIC would not "infringe on the liberty of individual Australians freely to express their opinions with respect to Rhodesia". After he received a copy of the draft bill in October, Peacock judged that it was "too dragnet in its approach" and directed that it be redrafted to better protect freedom of speech.[94] This deferment became indefinite. While the opposition Labor Party would have provided enough votes for the legislation to pass parliament, Fraser was not willing to expose himself and his government to a major backbench revolt over the issue.[92][95] The political scientist Alexander Lee has described the defeat of the legislation as "a stunning victory" for "Rhodesia's Australian allies", and noted that it meant that Australia did not comply with Resolution 409.[95]

Transition to majority rule in Rhodesia

[edit]In August 1978, the Fraser government passed legislation to force an unofficial embassy set up in Canberra by the Croatian independence campaigner Mario Despoja to close. The Labor Party opposition attempted to amend this bill to require that the government also legislate to close the RIC, but this amendment was defeated.[96] The Fraser government considered legislating the closure of the centre again in April 1979 ahead of an assessment by the United Nations Security Committee of countries' compliance with enforcing sanctions against Rhodesia.[97][98] At this time an election in Rhodesia was imminent, and the Cabinet was intending to take its outcomes into consideration when deciding how it would go about closing the centre.[99] An article in The Canberra Times stated that the Fraser government's efforts to close the centre were "moving with the slowness of the most lethargic sloth" and claimed that the centre was a red herring that was distracting attention away from the large number of Australians who were fighting with the Rhodesian Security Forces.[100]

The Rhodesian government that was elected agreed in December 1979 to a transition to majority rule. Under this agreement, the country reverted to the status of a British colony until a free and fair election was held in February 1980.[101] White minority rule ended in April 1980, with Rhodesia becoming the independent state of Zimbabwe. The Zimbabwean government decided that month to shut down the RIC.[3] It was renamed the Zimbabwe Information Centre for the last weeks of its existence, and closed on 31 May 1980.[102] A Zimbabwean high commission was established in Canberra during 1988.[103][104]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Bradley v Commonwealth [1973] HCA 34, (1973) 128 CLR 557 (10 September 1973), High Court.

- ^ Jansen 1998, p. 31.

- ^ a b "Zimbabwe closing Sydney office". The Canberra Times. 17 April 1980. p. 8. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Jordan 2020, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Minter & Schmidt 1988, pp. 211–213.

- ^ a b Geldenhuys 1990, p. 62.

- ^ a b Geldenhuys 1990, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Berry 2019, p. 510.

- ^ Berry 2019, pp. 505–508.

- ^ Brownell 2010, p. 480.

- ^ Brownell 2010, p. 487.

- ^ Berry 2019, pp. 509–510.

- ^ Geldenhuys 1990, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Jordan 2020, p. 78.

- ^ Londey, Crawley & Horner 2020, p. 612.

- ^ Jordan 2020, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Londey, Crawley & Horner 2020, pp. 612–613.

- ^ a b c d "Rhodesian Centre. Inquiry ordered by Mr Chipp". The Canberra Times. 3 April 1972. p. 7. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Jansen 1998, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Jordan 2017, pp. 908–909.

- ^ Jordan 2017, pp. xvi–xvii.

- ^ Londey, Crawley & Horner 2020, pp. 613–614, 616.

- ^ a b c d e Goldsworthy 1973, p. 66.

- ^ Mlambo 2019, p. 391.

- ^ "Rhodesian wheat 'humanitarian'". The Canberra Times. 22 May 1970. p. 9. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Geldenhuys 1990, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b c d e f Jordan 2017, p. 576.

- ^ Cresswell-George, T.A. (16 September 1966). "Rhodesia 'invaded'". The Canberra Times. p. 2. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Jordan 2017, p. 858.

- ^ a b c d e Jacobs, Michael (6 April 1972). "The Rhodesia Papers affair". The Canberra Times. p. 2. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Jordan 2017, p. 859.

- ^ a b c Hall 1972, p. 184.

- ^ "Rhodesian Embassy". Tharunka. 10 April 1973. p. 15. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Harcourt 1972, p. 113.

- ^ a b Galbally 1974, p. 1.

- ^ Jansen 1998, pp. 142–143.

- ^ "Aust soldiers fight as regulars". Papua New Guinea Post-courier. 3 November 1978. p. 8. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The 'mercenaries' in Rhodesia's Army". The Canberra Times. 7 January 1977. p. 5. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Greg Aplin Inaugural Speech" (PDF). Parliament of New South Wales. 21 May 2003. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ a b Hall 1972, p. 183.

- ^ Jordan 2017, p. xxxii.

- ^ a b Hall 1972, pp. 183–184.

- ^ "Freedom of Opinion". The Canberra Times. 30 August 1977. p. 2. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Jordan 2017, pp. 580–582.

- ^ a b c Hall 1972, p. 185.

- ^ a b Jordan 2017, p. 838.

- ^ Jordan 2017, pp. 838, 858, 860.

- ^ a b Jordan 2017, p. 879.

- ^ "Rhodesian Secrecy is Denied". The Sydney Morning Herald. 6 April 1972. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Cabinet considers Smith propaganda". The Guardian. 10 April 1972. p. 4. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "No action over Rhodesia centre". The Canberra Times. 11 April 1972. p. 3. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Timely hint from Africa". The Age. 7 July 1972. p. 9. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Racism "Ultimate Violence"". The Australian Jewish News. 12 May 1972. p. 2. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Jordan 2017, pp. xxxii, 839.

- ^ Jordan 2017, p. 839.

- ^ "No passport renewals for Ian Smith's men, Forbes rules". The Age. 6 July 1972. p. 1. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jordan 2017, pp. 904, 909.

- ^ Jordan 2017, pp. xxxii–xxxiii.

- ^ "Rhodesian woman 'refused entry'". The Canberra Times. 12 December 1972. p. 3. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Askin is angry at 'big heads'". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 December 1972. p. 1. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Loughnan 2014, p. 269.

- ^ a b Loughnan 2014, p. 270.

- ^ "Rhodesia". The Canberra Times. Vol. 47, no. 13, 373. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 3 March 1973. p. 3. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Judge says name can be cancelled". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 June 1973. p. 8. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rhodesia centre appeal fails". The Age. 13 June 1974. p. 12. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rhodesia centre's name 'can be cancelled'". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 June 1974. p. 12. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Durish, Peter (19 July 1975). "A lily by any other name..." The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 9. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rhodesian centre 'voice for blacks'". The Canberra Times. 19 December 1972. p. 7. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Discrimination is no laugh to Sekai". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 January 1973. p. 16. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Demonstrators burn flag". The Sydney Morning Herald. 30 March 1973. p. 11. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Rhodesia Centre arrests". Tribune. 28 August 1973. p. 2. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Hearing on ban by PMG". The Canberra Times. 5 May 1973. p. 7. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ "PMG action on centre 'invalid'". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 September 1973. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Centre bombed". The Canberra Times. 7 July 1973. p. 7. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Prime minister's press conference". The Canberra Times. 12 September 1973. p. 7. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Rhodesia legislation". The Canberra Times. 7 March 1974. p. 3. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Jansen 1998, p. 143.

- ^ "High Court stops bid to drop phone book entry". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 February 1975. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rhodesia gains a phone listing". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 August 1975. p. 12. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bomb blast at centre". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 March 1975. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jansen 1998, p. 271.

- ^ Lee 2020, pp. 506–507.

- ^ Marder, Murrey (1 June 1977). "Rhodesia Lobbying Office Seems About to Close". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "Security Council resolution 409 (1977)". United Nations. 27 May 1977. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Michael 2016, pp. 253–254.

- ^ a b Lee 2020, p. 513.

- ^ a b c Indyk 1977, p. 24.

- ^ Lee 2020, pp. 513–514.

- ^ "Backbench revolt possible over Rhodesia centre". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 August 1977. p. 8. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Liberal criticises Federal move on Rhodesia". The Canberra Times. 27 September 1977. p. 3. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "MP to quit". The Canberra Times. 20 September 1977. p. 3. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Indyk 1977, p. 25.

- ^ "Malcolm Fraser: elections". Australia's prime ministers. National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Indyk 1977, p. 26.

- ^ a b Lee 2020, p. 514.

- ^ "Stage set to close embassy". The Age. 18 August 1978. p. 15. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ "Peacock softens Rhodesia stand". The Canberra Times. 20 April 1979. p. 7. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Grattan, Michelle (17 April 1979). "New UN bid on Rhodesia centre likely". The Age. p. 12. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rhodesian poll will not affect centre's fate". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 April 1979. p. 27. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Andrews, Ross (21 April 1979). "The Week". The Canberra Times. p. 2. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Londey, Crawley & Horner 2020, pp. 616, 618, 624, 678.

- ^ Grattan, Michelle (16 April 1980). "Rhodesia will quit Sydney". The Age. p. 5. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zimbabwe". Foreign embassies and consulates in Australia. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "About us". Embassy of Zimbabwe in Australia. Retrieved 23 December 2022.[permanent dead link]

Works consulted

[edit]- Berry, Bruce (2019). "Flag Of Defiance: The International Use of the Rhodesian Flag Following UDI". South African Historical Journal. 71 (3): 495–517. doi:10.1080/02582473.2018.1561749. hdl:2263/71112. S2CID 149593650.

- Brownell, Josiah (September 2010). "'A Sordid Tussle on the Strand': Rhodesia House during the UDI Rebellion (1965–80)". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 38 (3): 471–499. doi:10.1080/03086534.2010.503398. S2CID 159761581.

- Galbally, Francis (1974). "Bradley v The Commonwealth (Ministerial Discretion)". Melbourne Law Review. 9 (4): 789–972.

- Geldenhuys, Deon (1990). Isolated States: A Comparative Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40268-2.

- Goldsworthy, David (1973). "Australia and Africa: New Relationships?". The Australian Quarterly. 45 (4): 58–72. doi:10.2307/20634597. JSTOR 20634597.

- Hall, Richard V. (1972). "Australia and Rhodesia: Black Interests and White Lies". In Stevens, F.S. (ed.). Racism: The Australian Experience. A Study of Race Prejudice in Australia. Volume 3: Colonialism. New York City: Taplinger Publishing Co. pp. 175–186. ISBN 978-0-8008-6582-5.

- Harcourt, David (1972). Everyone Wants to be Fuehrer: National Socialism in Australia and New Zealand. Cremorne, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. ISBN 978-0-207-12415-0.

- Indyk, Martin (1977). Influence Without Power: The Role of the Backbench in Australian Foreign Policy, 1976-1977. Canberra: Department of the Parliamentary Library Legislative Research Service. ISBN 978-0-642-91273-2.

- Jansen, Robert (1998). Australian Foreign Policy and Africa, 1972–1983 (PhD thesis). Canberra: Australian National University.

- Jordan, Matthew, ed. (2017). Australia and the Rhodesian Problem, 1961–1972. Documents on Australian Foreign Policy. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-74223-536-3.

- Jordan, Matthew (2020). "'Australia in this Matter is under Some Scrutiny': Early Australian Initiatives to the Rhodesian Problem, 1961–64". The International History Review. 42 (1): 77–98. doi:10.1080/07075332.2018.1555179. S2CID 159260364.

- Lee, Alexander (September 2020). "Conservatives Divided: Defending Rhodesia Against Malcolm Fraser 1976-1978". Australian Journal of Politics & History. 66 (3): 503–521. doi:10.1111/ajph.12701. S2CID 225329379.

- Londey, Peter; Crawley, Rhys; Horner, David (2020). The Long Search for Peace: Observer Missions and Beyond, 1947–2006. Official History of Australian Peacekeeping, Humanitarian and Post-Cold War Operations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-62893-8.

- Loughnan, Paul Ernest (2014). A History of the Askin Government 1965-1975 (PhD thesis) (Thesis). Armidale, New South Wales: University of New England.

- Michael, Edward R. (2016). The White House and White Africa: Presidential Policy on Rhodesia 1965–79 (PhD thesis). Birmingham: University of Birmingham. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Minter, William; Schmidt, Elizabeth (April 1988). "When Sanctions Worked: The Case of Rhodesia Reexamined". African Affairs. 87 (347): 207–237. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098017. JSTOR 722401.

- Mlambo, Alois S. (2019). "'Honoured More in the Breach than in the Observance': Economic Sanctions on Rhodesia and International Response, 1965 to 1979". South African Historical Journal. 71 (3): 371–393. doi:10.1080/02582473.2019.1598478. hdl:2263/70331. S2CID 151104573.

- History of the foreign relations of Australia

- 1966 establishments in Australia

- Foreign relations of Rhodesia

- De facto embassies

- Diplomatic missions in Australia

- 1980 disestablishments in Australia

- Australia–Zimbabwe relations

- Political history of Australia

- Propaganda organizations

- Australia and the Commonwealth of Nations

- Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth of Nations