Patterns in nature

Patterns in nature are visible regularities of form found in the natural world. These patterns recur in different contexts and can sometimes be modelled mathematically. Natural patterns include symmetries, trees, spirals, meanders, waves, foams, tessellations, cracks and stripes.[1] Early Greek philosophers studied pattern, with Plato, Pythagoras and Empedocles attempting to explain order in nature. The modern understanding of visible patterns developed gradually over time.

In the 19th century, the Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau examined soap films, leading him to formulate the concept of a minimal surface. The German biologist and artist Ernst Haeckel painted hundreds of marine organisms to emphasise their symmetry. Scottish biologist D'Arcy Thompson pioneered the study of growth patterns in both plants and animals, showing that simple equations could explain spiral growth. In the 20th century, the British mathematician Alan Turing predicted mechanisms of morphogenesis which give rise to patterns of spots and stripes. The Hungarian biologist Aristid Lindenmayer and the French American mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot showed how the mathematics of fractals could create plant growth patterns.

Mathematics, physics and chemistry can explain patterns in nature at different levels and scales. Patterns in living things are explained by the biological processes of natural selection and sexual selection. Studies of pattern formation make use of computer models to simulate a wide range of patterns.

History

[edit]Early Greek philosophers attempted to explain order in nature, anticipating modern concepts. Pythagoras (c. 570–c. 495 BC) explained patterns in nature like the harmonies of music as arising from number, which he took to be the basic constituent of existence.[a] Empedocles (c. 494–c. 434 BC) to an extent anticipated Darwin's evolutionary explanation for the structures of organisms.[b] Plato (c. 427–c. 347 BC) argued for the existence of natural universals. He considered these to consist of ideal forms (εἶδος eidos: "form") of which physical objects are never more than imperfect copies. Thus, a flower may be roughly circular, but it is never a perfect circle.[2] Theophrastus (c. 372–c. 287 BC) noted that plants "that have flat leaves have them in a regular series"; Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) noted their patterned circular arrangement.[3] Centuries later, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) noted the spiral arrangement of leaf patterns, that tree trunks gain successive rings as they age, and proposed a rule purportedly satisfied by the cross-sectional areas of tree-branches.[4][3]

In 1202, Leonardo Fibonacci introduced the Fibonacci sequence to the western world with his book Liber Abaci.[5] Fibonacci presented a thought experiment on the growth of an idealized rabbit population.[6] Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) pointed out the presence of the Fibonacci sequence in nature, using it to explain the pentagonal form of some flowers.[3] In 1658, the English physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne discussed "how Nature Geometrizeth" in The Garden of Cyrus, citing Pythagorean numerology involving the number 5, and the Platonic form of the quincunx pattern. The discourse's central chapter features examples and observations of the quincunx in botany.[7] In 1754, Charles Bonnet observed that the spiral phyllotaxis of plants were frequently expressed in both clockwise and counter-clockwise golden ratio series.[3] Mathematical observations of phyllotaxis followed with Karl Friedrich Schimper and his friend Alexander Braun's 1830 and 1830 work, respectively; Auguste Bravais and his brother Louis connected phyllotaxis ratios to the Fibonacci sequence in 1837, also noting its appearance in pinecones and pineapples.[3] In his 1854 book, German psychologist Adolf Zeising explored the golden ratio expressed in the arrangement of plant parts, the skeletons of animals and the branching patterns of their veins and nerves, as well as in crystals.[8][9][10]

In the 19th century, the Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau (1801–1883) formulated the mathematical problem of the existence of a minimal surface with a given boundary, which is now named after him. He studied soap films intensively, formulating Plateau's laws which describe the structures formed by films in foams.[11] Lord Kelvin identified the problem of the most efficient way to pack cells of equal volume as a foam in 1887; his solution uses just one solid, the bitruncated cubic honeycomb with very slightly curved faces to meet Plateau's laws. No better solution was found until 1993 when Denis Weaire and Robert Phelan proposed the Weaire–Phelan structure; the Beijing National Aquatics Center adapted the structure for their outer wall in the 2008 Summer Olympics.[12] Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919) painted beautiful illustrations of marine organisms, in particular Radiolaria, emphasising their symmetry to support his faux-Darwinian theories of evolution.[13] The American photographer Wilson Bentley took the first micrograph of a snowflake in 1885.[14]

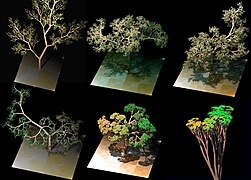

In the 20th century, A. H. Church studied the patterns of phyllotaxis in his 1904 book.[15] In 1917, D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson published On Growth and Form; his description of phyllotaxis and the Fibonacci sequence, the mathematical relationships in the spiral growth patterns of plants showed that simple equations could describe the spiral growth patterns of animal horns and mollusc shells.[16] In 1952, the computer scientist Alan Turing (1912–1954) wrote The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis, an analysis of the mechanisms that would be needed to create patterns in living organisms, in the process called morphogenesis.[17] He predicted oscillating chemical reactions, in particular the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction. These activator-inhibitor mechanisms can, Turing suggested, generate patterns (dubbed "Turing patterns") of stripes and spots in animals, and contribute to the spiral patterns seen in plant phyllotaxis.[18] In 1968, the Hungarian theoretical biologist Aristid Lindenmayer (1925–1989) developed the L-system, a formal grammar which can be used to model plant growth patterns in the style of fractals.[19] L-systems have an alphabet of symbols that can be combined using production rules to build larger strings of symbols, and a mechanism for translating the generated strings into geometric structures. In 1975, after centuries of slow development of the mathematics of patterns by Gottfried Leibniz, Georg Cantor, Helge von Koch, Wacław Sierpiński and others, Benoît Mandelbrot wrote a famous paper, How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension, crystallising mathematical thought into the concept of the fractal.[20]

-

Fibonacci number patterns occur widely in plants such as this queen sago, Cycas circinalis.

-

Beijing's National Aquatics Center for the 2008 Olympic games has a Weaire–Phelan structure.

-

D'Arcy Thompson pioneered the study of growth and form in his 1917 book.

Causes

[edit]

Living things like orchids, hummingbirds, and the peacock's tail have abstract designs with a beauty of form, pattern and colour that artists struggle to match.[21] The beauty that people perceive in nature has causes at different levels, notably in the mathematics that governs what patterns can physically form, and among living things in the effects of natural selection, that govern how patterns evolve.[22]

Mathematics seeks to discover and explain abstract patterns or regularities of all kinds.[23][24] Visual patterns in nature find explanations in chaos theory, fractals, logarithmic spirals, topology and other mathematical patterns. For example, L-systems form convincing models of different patterns of tree growth.[19]

The laws of physics apply the abstractions of mathematics to the real world, often as if it were perfect. For example, a crystal is perfect when it has no structural defects such as dislocations and is fully symmetric. Exact mathematical perfection can only approximate real objects.[25] Visible patterns in nature are governed by physical laws; for example, meanders can be explained using fluid dynamics.

In biology, natural selection can cause the development of patterns in living things for several reasons, including camouflage,[26] sexual selection,[26] and different kinds of signalling, including mimicry[27] and cleaning symbiosis.[28] In plants, the shapes, colours, and patterns of insect-pollinated flowers like the lily have evolved to attract insects such as bees. Radial patterns of colours and stripes, some visible only in ultraviolet light serve as nectar guides that can be seen at a distance.[29]

Types of pattern

[edit]Symmetry

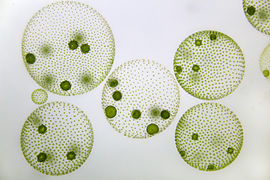

[edit]Symmetry is pervasive in living things. Animals mainly have bilateral or mirror symmetry, as do the leaves of plants and some flowers such as orchids.[30] Plants often have radial or rotational symmetry, as do many flowers and some groups of animals such as sea anemones. Fivefold symmetry is found in the echinoderms, the group that includes starfish, sea urchins, and sea lilies.[31]

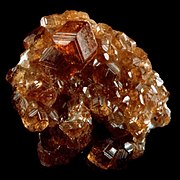

Among non-living things, snowflakes have striking sixfold symmetry; each flake's structure forms a record of the varying conditions during its crystallization, with nearly the same pattern of growth on each of its six arms.[32] Crystals in general have a variety of symmetries and crystal habits; they can be cubic or octahedral, but true crystals cannot have fivefold symmetry (unlike quasicrystals).[33] Rotational symmetry is found at different scales among non-living things, including the crown-shaped splash pattern formed when a drop falls into a pond,[34] and both the spheroidal shape and rings of a planet like Saturn.[35]

Symmetry has a variety of causes. Radial symmetry suits organisms like sea anemones whose adults do not move: food and threats may arrive from any direction. But animals that move in one direction necessarily have upper and lower sides, head and tail ends, and therefore a left and a right. The head becomes specialised with a mouth and sense organs (cephalisation), and the body becomes bilaterally symmetric (though internal organs need not be).[36] More puzzling is the reason for the fivefold (pentaradiate) symmetry of the echinoderms. Early echinoderms were bilaterally symmetrical, as their larvae still are. Sumrall and Wray argue that the loss of the old symmetry had both developmental and ecological causes.[37] In the case of ice eggs, the gentle churn of water, blown by a suitably stiff breeze makes concentric layers of ice form on a seed particle that then grows into a floating ball as it rolls through the freezing currents.[38]

-

Animals often show mirror or bilateral symmetry, like this tiger.

-

Fivefold symmetry can be seen in many flowers and some fruits like this medlar.

-

Snowflakes have sixfold symmetry.

-

Fluorite showing cubic crystal habit.

-

Water splash approximates radial symmetry.

-

Garnet showing rhombic dodecahedral crystal habit.

-

Volvox has spherical symmetry.

-

Ice eggs gain spherical symmetry by being rolled about by wind and currents.

Trees, fractals

[edit]The branching pattern of trees was described in the Italian Renaissance by Leonardo da Vinci. In A Treatise on Painting he stated that:

All the branches of a tree at every stage of its height when put together are equal in thickness to the trunk [below them].[39]

A more general version states that when a parent branch splits into two or more child branches, the surface areas of the child branches add up to that of the parent branch.[40] An equivalent formulation is that if a parent branch splits into two child branches, then the cross-sectional diameters of the parent and the two child branches form a right-angled triangle. One explanation is that this allows trees to better withstand high winds.[40] Simulations of biomechanical models agree with the rule.[41]

Fractals are infinitely self-similar, iterated mathematical constructs having fractal dimension.[20][42][43] Infinite iteration is not possible in nature so all 'fractal' patterns are only approximate. For example, the leaves of ferns and umbellifers (Apiaceae) are only self-similar (pinnate) to 2, 3 or 4 levels. Fern-like growth patterns occur in plants and in animals including bryozoa, corals, hydrozoa like the air fern, Sertularia argentea, and in non-living things, notably electrical discharges. Lindenmayer system fractals can model different patterns of tree growth by varying a small number of parameters including branching angle, distance between nodes or branch points (internode length), and number of branches per branch point.[19]

Fractal-like patterns occur widely in nature, in phenomena as diverse as clouds, river networks, geologic fault lines, mountains, coastlines,[44] animal coloration, snow flakes,[45] crystals,[46] blood vessel branching,[47] Purkinje cells,[48] actin cytoskeletons,[49] and ocean waves.[50]

-

The growth patterns of certain trees resemble these Lindenmayer system fractals.

-

Branching pattern of a baobab tree

-

Leaf of cow parsley, Anthriscus sylvestris, is 2- or 3-pinnate, not infinite

-

Trees: dendritic copper crystals (in microscope)

Spirals

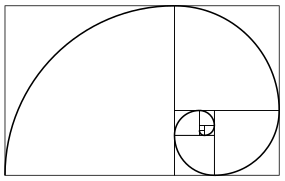

[edit]Spirals are common in plants and in some animals, notably molluscs. For example, in the nautilus, a cephalopod mollusc, each chamber of its shell is an approximate copy of the next one, scaled by a constant factor and arranged in a logarithmic spiral.[51] Given a modern understanding of fractals, a growth spiral can be seen as a special case of self-similarity.[52]

Plant spirals can be seen in phyllotaxis, the arrangement of leaves on a stem, and in the arrangement (parastichy[53]) of other parts as in composite flower heads and seed heads like the sunflower or fruit structures like the pineapple[15][54]: 337 and snake fruit, as well as in the pattern of scales in pine cones, where multiple spirals run both clockwise and anticlockwise. These arrangements have explanations at different levels – mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology – each individually correct, but all necessary together.[55] Phyllotaxis spirals can be generated from Fibonacci ratios: the Fibonacci sequence runs 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13... (each subsequent number being the sum of the two preceding ones). For example, when leaves alternate up a stem, one rotation of the spiral touches two leaves, so the pattern or ratio is 1/2. In hazel the ratio is 1/3; in apricot it is 2/5; in pear it is 3/8; in almond it is 5/13.[56] Animal behaviour can yield spirals; for example, acorn worms leave spiral fecal trails on the sea floor.[57]

In disc phyllotaxis as in the sunflower and daisy, the florets are arranged along Fermat's spiral, but this is disguised because successive florets are spaced far apart, by the golden angle, 137.508° (dividing the circle in the golden ratio); when the flowerhead is mature so all the elements are the same size, this spacing creates a Fibonacci number of more obvious spirals.[58]

From the point of view of physics, spirals are lowest-energy configurations[59] which emerge spontaneously through self-organizing processes in dynamic systems.[60] From the point of view of chemistry, a spiral can be generated by a reaction-diffusion process, involving both activation and inhibition. Phyllotaxis is controlled by proteins that manipulate the concentration of the plant hormone auxin, which activates meristem growth, alongside other mechanisms to control the relative angle of buds around the stem.[61] From a biological perspective, arranging leaves as far apart as possible in any given space is favoured by natural selection as it maximises access to resources, especially sunlight for photosynthesis.[54]

-

Fibonacci spiral

-

Bighorn sheep, Ovis canadensis

-

Spirals: phyllotaxis of spiral aloe, Aloe polyphylla

-

Nautilus shell's logarithmic growth spiral

-

Fermat's spiral: seed head of sunflower, Helianthus annuus

-

Multiple Fibonacci spirals: red cabbage in cross section

-

Spiralling shell of Trochoidea liebetruti

-

Water droplets fly off a wet, spinning ball in equiangular spirals

Chaos, flow, meanders

[edit]In mathematics, a dynamical system is chaotic if it is (highly) sensitive to initial conditions (the so-called "butterfly effect"[62]), which requires the mathematical properties of topological mixing and dense periodic orbits.[63]

Alongside fractals, chaos theory ranks as an essentially universal influence on patterns in nature. There is a relationship between chaos and fractals—the strange attractors in chaotic systems have a fractal dimension.[64] Some cellular automata, simple sets of mathematical rules that generate patterns, have chaotic behaviour, notably Stephen Wolfram's Rule 30.[65]

Vortex streets are zigzagging patterns of whirling vortices created by the unsteady separation of flow of a fluid, most often air or water, over obstructing objects.[66] Smooth (laminar) flow starts to break up when the size of the obstruction or the velocity of the flow become large enough compared to the viscosity of the fluid.

Meanders are sinuous bends in rivers or other channels, which form as a fluid, most often water, flows around bends. As soon as the path is slightly curved, the size and curvature of each loop increases as helical flow drags material like sand and gravel across the river to the inside of the bend. The outside of the loop is left clean and unprotected, so erosion accelerates, further increasing the meandering in a powerful positive feedback loop.[67]

-

Chaos: shell of gastropod mollusc the cloth of gold cone, Conus textile, resembles Rule 30 cellular automaton

-

Flow: vortex street of clouds at Juan Fernandez Islands

-

Meanders: dramatic meander scars and oxbow lakes in the broad flood plain of the Rio Negro, seen from space

-

Meanders: sinuous path of Rio Cauto, Cuba

-

Meanders: sinuous snake crawling

-

Meanders: symmetrical brain coral, Diploria strigosa

Waves, dunes

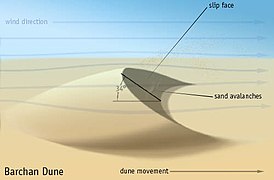

[edit]Waves are disturbances that carry energy as they move. Mechanical waves propagate through a medium – air or water, making it oscillate as they pass by.[68] Wind waves are sea surface waves that create the characteristic chaotic pattern of any large body of water, though their statistical behaviour can be predicted with wind wave models.[69] As waves in water or wind pass over sand, they create patterns of ripples. When winds blow over large bodies of sand, they create dunes, sometimes in extensive dune fields as in the Taklamakan desert. Dunes may form a range of patterns including crescents, very long straight lines, stars, domes, parabolas, and longitudinal or seif ('sword') shapes.[70]

Barchans or crescent dunes are produced by wind acting on desert sand; the two horns of the crescent and the slip face point downwind. Sand blows over the upwind face, which stands at about 15 degrees from the horizontal, and falls onto the slip face, where it accumulates up to the angle of repose of the sand, which is about 35 degrees. When the slip face exceeds the angle of repose, the sand avalanches, which is a nonlinear behaviour: the addition of many small amounts of sand causes nothing much to happen, but then the addition of a further small amount suddenly causes a large amount to avalanche.[71] Apart from this nonlinearity, barchans behave rather like solitary waves.[72]

-

Waves: breaking wave in a ship's wake

-

Dunes: sand dunes in Taklamakan desert, from space

-

Dunes: barchan crescent sand dune

Bubbles, foam

[edit]A soap bubble forms a sphere, a surface with minimal area (minimal surface) — the smallest possible surface area for the volume enclosed. Two bubbles together form a more complex shape: the outer surfaces of both bubbles are spherical; these surfaces are joined by a third spherical surface as the smaller bubble bulges slightly into the larger one.[11]

A foam is a mass of bubbles; foams of different materials occur in nature. Foams composed of soap films obey Plateau's laws, which require three soap films to meet at each edge at 120° and four soap edges to meet at each vertex at the tetrahedral angle of about 109.5°. Plateau's laws further require films to be smooth and continuous, and to have a constant average curvature at every point. For example, a film may remain nearly flat on average by being curved up in one direction (say, left to right) while being curved downwards in another direction (say, front to back).[73][74] Structures with minimal surfaces can be used as tents.

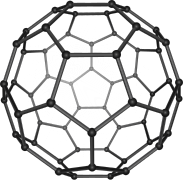

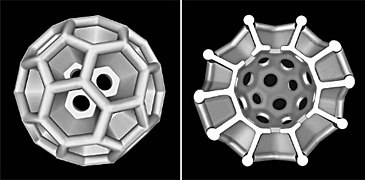

At the scale of living cells, foam patterns are common; radiolarians, sponge spicules, silicoflagellate exoskeletons and the calcite skeleton of a sea urchin, Cidaris rugosa, all resemble mineral casts of Plateau foam boundaries.[75][76] The skeleton of the Radiolarian, Aulonia hexagona, a beautiful marine form drawn by Ernst Haeckel, looks as if it is a sphere composed wholly of hexagons, but this is mathematically impossible. The Euler characteristic states that for any convex polyhedron, the number of faces plus the number of vertices (corners) equals the number of edges plus two. A result of this formula is that any closed polyhedron of hexagons has to include exactly 12 pentagons, like a soccer ball, Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome, or fullerene molecule. This can be visualised by noting that a mesh of hexagons is flat like a sheet of chicken wire, but each pentagon that is added forces the mesh to bend (there are fewer corners, so the mesh is pulled in).[77]

-

Foam of soap bubbles: four edges meet at each vertex, at angles close to 109.5°, as in two C-H bonds in methane.

-

Radiolaria drawn by Haeckel in his Kunstformen der Natur (1904).

-

Haeckel's Spumellaria; the skeletons of these Radiolaria have foam-like forms.

-

Buckminsterfullerene C60: Richard Smalley and colleagues synthesised the fullerene molecule in 1985.

-

Brochosomes (secretory microparticles produced by leafhoppers) often approximate fullerene geometry.

-

Equal spheres (gas bubbles) in a surface foam

-

Circus tent approximates a minimal surface.

Tessellations

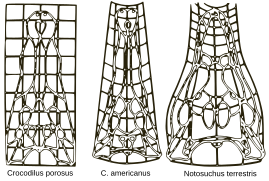

[edit]Tessellations are patterns formed by repeating tiles all over a flat surface. There are 17 wallpaper groups of tilings.[78] While common in art and design, exactly repeating tilings are less easy to find in living things. The cells in the paper nests of social wasps, and the wax cells in honeycomb built by honey bees are well-known examples. Among animals, bony fish, reptiles or the pangolin, or fruits like the salak are protected by overlapping scales or osteoderms, these form more-or-less exactly repeating units, though often the scales in fact vary continuously in size. Among flowers, the snake's head fritillary, Fritillaria meleagris, have a tessellated chequerboard pattern on their petals. The structures of minerals provide good examples of regularly repeating three-dimensional arrays. Despite the hundreds of thousands of known minerals, there are rather few possible types of arrangement of atoms in a crystal, defined by crystal structure, crystal system, and point group; for example, there are exactly 14 Bravais lattices for the 7 lattice systems in three-dimensional space.[79]

-

Crystals: cube-shaped crystals of halite (rock salt); cubic crystal system, isometric hexoctahedral crystal symmetry

-

Arrays: honeycomb is a natural tessellation

-

Tilings: tessellated flower of snake's head fritillary, Fritillaria meleagris

-

Tilings: overlapping scales of common roach, Rutilus rutilus

-

Tilings: overlapping scales of snakefruit or salak, Salacca zalacca

-

Tessellated pavement: a rare rock formation on the Tasman Peninsula

Cracks

[edit]Cracks are linear openings that form in materials to relieve stress. When an elastic material stretches or shrinks uniformly, it eventually reaches its breaking strength and then fails suddenly in all directions, creating cracks with 120 degree joints, so three cracks meet at a node. Conversely, when an inelastic material fails, straight cracks form to relieve the stress. Further stress in the same direction would then simply open the existing cracks; stress at right angles can create new cracks, at 90 degrees to the old ones. Thus the pattern of cracks indicates whether the material is elastic or not.[80] In a tough fibrous material like oak tree bark, cracks form to relieve stress as usual, but they do not grow long as their growth is interrupted by bundles of strong elastic fibres. Since each species of tree has its own structure at the levels of cell and of molecules, each has its own pattern of splitting in its bark.[81]

-

Old pottery surface, white glaze with mainly 90° cracks

-

Drying inelastic mud in the Rann of Kutch with mainly 90° cracks

-

Drying elastic mud in Sicily with mainly 120° cracks

-

Cooled basalt at Giant's Causeway. Vertical mainly 120° cracks giving hexagonal columns

-

Palm trunk with branching vertical cracks (and horizontal leaf scars)

Spots, stripes

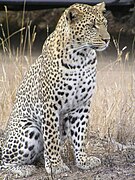

[edit]Leopards and ladybirds are spotted; angelfish and zebras are striped.[82] These patterns have an evolutionary explanation: they have functions which increase the chances that the offspring of the patterned animal will survive to reproduce. One function of animal patterns is camouflage;[26] for instance, a leopard that is harder to see catches more prey. Another function is signalling[27] — for instance, a ladybird is less likely to be attacked by predatory birds that hunt by sight, if it has bold warning colours, and is also distastefully bitter or poisonous, or mimics other distasteful insects. A young bird may see a warning patterned insect like a ladybird and try to eat it, but it will only do this once; very soon it will spit out the bitter insect; the other ladybirds in the area will remain undisturbed. The young leopards and ladybirds, inheriting genes that somehow create spottedness, survive. But while these evolutionary and functional arguments explain why these animals need their patterns, they do not explain how the patterns are formed.[82]

-

Dirce beauty butterfly, Colobura dirce

-

Grevy's zebra, Equus grevyi

-

Royal angelfish, Pygoplites diacanthus

-

Leopard, Panthera pardus pardus

-

Array of ladybirds by G.G. Jacobson

-

Breeding pattern of cuttlefish, Sepia officinalis

Pattern formation

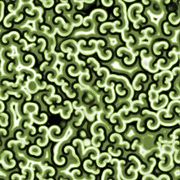

[edit]Alan Turing,[17] and later the mathematical biologist James Murray,[83] described a mechanism that spontaneously creates spotted or striped patterns: a reaction–diffusion system.[84] The cells of a young organism have genes that can be switched on by a chemical signal, a morphogen, resulting in the growth of a certain type of structure, say a darkly pigmented patch of skin. If the morphogen is present everywhere, the result is an even pigmentation, as in a black leopard. But if it is unevenly distributed, spots or stripes can result. Turing suggested that there could be feedback control of the production of the morphogen itself. This could cause continuous fluctuations in the amount of morphogen as it diffused around the body. A second mechanism is needed to create standing wave patterns (to result in spots or stripes): an inhibitor chemical that switches off production of the morphogen, and that itself diffuses through the body more quickly than the morphogen, resulting in an activator-inhibitor scheme. The Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction is a non-biological example of this kind of scheme, a chemical oscillator.[84]

Later research has managed to create convincing models of patterns as diverse as zebra stripes, giraffe blotches, jaguar spots (medium-dark patches surrounded by dark broken rings) and ladybird shell patterns (different geometrical layouts of spots and stripes, see illustrations).[85] Richard Prum's activation-inhibition models, developed from Turing's work, use six variables to account for the observed range of nine basic within-feather pigmentation patterns, from the simplest, a central pigment patch, via concentric patches, bars, chevrons, eye spot, pair of central spots, rows of paired spots and an array of dots.[86][87] More elaborate models simulate complex feather patterns in the guineafowl Numida meleagris in which the individual feathers feature transitions from bars at the base to an array of dots at the far (distal) end. These require an oscillation created by two inhibiting signals, with interactions in both space and time.[87]

Patterns can form for other reasons in the vegetated landscape of tiger bush[88] and fir waves.[89] Tiger bush stripes occur on arid slopes where plant growth is limited by rainfall. Each roughly horizontal stripe of vegetation effectively collects the rainwater from the bare zone immediately above it.[88] Fir waves occur in forests on mountain slopes after wind disturbance, during regeneration. When trees fall, the trees that they had sheltered become exposed and are in turn more likely to be damaged, so gaps tend to expand downwind. Meanwhile, on the windward side, young trees grow, protected by the wind shadow of the remaining tall trees.[89] Natural patterns are sometimes formed by animals, as in the Mima mounds of the Northwestern United States and some other areas, which appear to be created over many years by the burrowing activities of pocket gophers,[90] while the so-called fairy circles of Namibia appear to be created by the interaction of competing groups of sand termites, along with competition for water among the desert plants.[91]

In permafrost soils with an active upper layer subject to annual freeze and thaw, patterned ground can form, creating circles, nets, ice wedge polygons, steps, and stripes. Thermal contraction causes shrinkage cracks to form; in a thaw, water fills the cracks, expanding to form ice when next frozen, and widening the cracks into wedges. These cracks may join up to form polygons and other shapes.[92]

The fissured pattern that develops on vertebrate brains is caused by a physical process of constrained expansion dependent on two geometric parameters: relative tangential cortical expansion and relative thickness of the cortex. Similar patterns of gyri (peaks) and sulci (troughs) have been demonstrated in models of the brain starting from smooth, layered gels, with the patterns caused by compressive mechanical forces resulting from the expansion of the outer layer (representing the cortex) after the addition of a solvent. Numerical models in computer simulations support natural and experimental observations that the surface folding patterns increase in larger brains.[93][94]

-

Giant pufferfish, Tetraodon mbu

-

Detail of giant pufferfish skin pattern

-

Snapshot of simulation of Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction

-

Helmeted guineafowl, Numida meleagris, feathers transition from barred to spotted, both in-feather and across the bird

-

Fairy circles in the Marienflusstal area in Namibia

See also

[edit]- Developmental biology

- Emergence

- Evolutionary history of plants

- Mathematics and art

- Morphogenesis

- Pattern formation

- Widmanstätten pattern

References

[edit]Footnotes

- ^ The so-called Pythagoreans, who were the first to take up mathematics, not only advanced this subject, but saturated with it, they fancied that the principles of mathematics were the principles of all things. Aristotle, Metaphysics 1–5 , c. 350 BC

- ^ Aristotle reports Empedocles arguing that, "[w]herever, then, everything turned out as it would have if it were happening for a purpose, there the creatures survived, being accidentally compounded in a suitable way; but where this did not happen, the creatures perished." The Physics, B8, 198b29 in Kirk, et al., 304).

Citations

- ^ Stevens 1974, p. 3.

- ^ Balaguer, Mark (7 April 2009) [2004]. "Platonism in Metaphysics". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Livio, Mario (2003) [2002]. The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number (First trade paperback ed.). New York: Broadway Books. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7679-0816-0.

- ^ Da Vinci, Leonardo (1971). Taylor, Pamela (ed.). The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. New American Library. p. 121.

- ^ Singh, Parmanand (1986). "Acharya Hemachandra and the (so called) Fibonacci Numbers". Mathematics Education Siwan. 20 (1): 28–30. ISSN 0047-6269.

- ^ Knott, Ron. "Fibonacci's Rabbits". University of Surrey Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences.

- ^ Browne, Thomas (1658). "Chapter III". The Garden of Cyrus.

- ^ Padovan, Richard (1999). Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 305–306. ISBN 978-0-419-22780-9.

- ^ Padovan, Richard (2002). "Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture". Nexus Network Journal. 4 (1): 113–122. doi:10.1007/s00004-001-0008-7.

- ^ Zeising, Adolf (1854). Neue Lehre van den Proportionen des meschlischen Körpers. preface.

- ^ a b Stewart 2001, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Ball 2009a, pp. 73–76.

- ^ Ball 2009a, p. 41.

- ^ Hannavy, John (2007). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Vol. 1. CRC Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-415-97235-2.

- ^ a b Livio, Mario (2003) [2002]. The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number. New York: Broadway Books. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-7679-0816-0.

- ^ About D'Arcy Archived 2017-07-01 at the Wayback Machine. D' Arcy 150. University of Dundee and the University of St Andrews. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ a b Turing, A. M. (1952). "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 237 (641): 37–72. Bibcode:1952RSPTB.237...37T. doi:10.1098/rstb.1952.0012. S2CID 937133.

- ^ Ball 2009a, pp. 163, 247–250.

- ^ a b c Rozenberg, Grzegorz; Salomaa, Arto. The Mathematical Theory of L Systems. Academic Press, New York, 1980. ISBN 0-12-597140-0

- ^ a b Mandelbrot, Benoît B. (1983). The fractal geometry of nature. Macmillan.

- ^ Forbes, Peter. All that useless beauty. The Guardian. Review: Non-fiction. 11 February 2012.

- ^ Stevens 1974, p. 222.

- ^ Steen, L.A. (1988). "The Science of Patterns". Science. 240 (4852): 611–616. Bibcode:1988Sci...240..611S. doi:10.1126/science.240.4852.611. PMID 17840903. S2CID 4849363. Archived from the original on 2010-10-28. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ Devlin, Keith. Mathematics: The Science of Patterns: The Search for Order in Life, Mind and the Universe (Scientific American Paperback Library) 1996

- ^ Tatarkiewicz, Władysław. "Perfection in the Sciences. II. Perfection in Physics and Chemistry". Dialectics and Humanism. 7 (2 (spring 1980)): 139.

- ^ a b c Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of Species. 1859, chapter 4.

- ^ a b Wickler, Wolfgang (1968). Mimicry in plants and animals. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Poulin, R.; Grutter, A.S. (1996). "Cleaning symbioses: proximate and adaptive explanations". BioScience. 46 (7): 512–517. doi:10.2307/1312929. JSTOR 1312929.

- ^ Koning, Ross (1994). "Plant Physiology Information Website". Pollination Adaptations. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Stewart 2001, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Stewart 2001, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Stewart 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Stewart 2001, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Stewart 2001, p. 60.

- ^ Stewart 2001, p. 71.

- ^ Hickman, Cleveland P.; Roberts, Larry S.; Larson, Allan (2002). "Animal Diversity" (PDF). Chapter 8: Acoelomate Bilateral Animals (Third ed.). p. 139. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Sumrall, Colin D.; Wray, Gregory A. (January 2007). "Ontogeny in the fossil record: diversification of body plans and the evolution of "aberrant" symmetry in Paleozoic echinoderms". Paleobiology. 33 (1): 149–163. Bibcode:2007Pbio...33..149S. doi:10.1666/06053.1. JSTOR 4500143. S2CID 84195721.

- ^ "Image of the Week – Goodness gracious, great balls of ice!". Cryospheric Sciences. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- ^ Richter, Jean Paul, ed. (1970) [1880]. The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-22572-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Palca, Joe (December 26, 2011). "The Wisdom of Trees (Leonardo Da Vinci Knew It)". Morning Edition. NPR. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Minamino, Ryoko; Tateno, Masaki (2014). "Tree Branching: Leonardo da Vinci's Rule versus Biomechanical Models". PLoS One. Vol. 9, no. 4. p. e93535. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093535.

- ^ Falconer, Kenneth (2003). Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications. John Wiley.

- ^ Briggs, John (1992). Fractals:The Patterns of Chaos. Thames and Hudson. p. 148.

- ^ Batty, Michael (4 April 1985). "Fractals – Geometry Between Dimensions". New Scientist. 105 (1450): 31.

- ^ Meyer, Yves; Roques, Sylvie (1993). Progress in wavelet analysis and applications: proceedings of the International Conference "Wavelets and Applications," Toulouse, France – June 1992. Atlantica Séguier Frontières. p. 25. ISBN 9782863321300.

- ^ Carbone, Alessandra; Gromov, Mikhael; Prusinkiewicz, Przemyslaw (2000). Pattern formation in biology, vision and dynamics. World Scientific. p. 78. ISBN 978-9810237929.

- ^ Hahn, Horst K.; Georg, Manfred; Peitgen, Heinz-Otto (2005). "Fractal aspects of three-dimensional vascular constructive optimization". In Losa, Gabriele A.; Nonnenmacher, Theo F. (eds.). Fractals in biology and medicine. Springer. pp. 55–66.

- ^ Takeda, T; Ishikawa, A; Ohtomo, K; Kobayashi, Y; Matsuoka, T (February 1992). "Fractal dimension of dendritic tree of cerebellar Purkinje cell during onto- and phylogenetic development". Neurosci Research. 13 (1): 19–31. doi:10.1016/0168-0102(92)90031-7. PMID 1314350. S2CID 4158401.

- ^ Sadegh, Sanaz (2017). "Plasma Membrane is Compartmentalized by a Self-Similar Cortical Actin Meshwork". Physical Review X. 7 (1): 011031. arXiv:1702.03997. Bibcode:2017PhRvX...7a1031S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.7.011031. PMC 5500227. PMID 28690919.

- ^ Addison, Paul S. (1997). Fractals and chaos: an illustrated course. CRC Press. pp. 44–46.

- ^ Maor, Eli. e: The Story of a Number. Princeton University Press, 2009. Page 135.

- ^ Ball 2009a, pp. 29–32.

- ^ "Spiral Lattices & Parastichy". Smith College. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ a b Kappraff, Jay (2004). "Growth in Plants: A Study in Number" (PDF). Forma. 19: 335–354. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ Ball 2009a, p. 13.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1961). Introduction to geometry. Wiley. p. 169.

- ^ Smith Jr., K.L.; Holland, N.D.; Ruhl, H.A. (2005). "Enteropneust production of spiral fecal trails on the deep-sea floor observed with time-lapse photography". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 52 (7): 1228–1240. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2005.02.004.

- ^ Prusinkiewicz, Przemyslaw; Lindenmayer, Aristid (1990). The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants. Springer-Verlag. pp. 101–107. ISBN 978-0-387-97297-8.

- ^ Levitov, L. S. (15 March 1991). "Energetic Approach to Phyllotaxis". Europhysics Letters. 14 (6): 533–539. Bibcode:1991EL.....14..533L. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/14/6/006. S2CID 250864634.

- ^ Douady, S.; Couder, Y. (March 1992). "Phyllotaxis as a physical self-organized growth process". Physical Review Letters. 68 (13): 2098–2101. Bibcode:1992PhRvL..68.2098D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.2098. PMID 10045303.

- ^ Ball 2009a, pp. 163, 249–250.

- ^ Lorenz, Edward N. (March 1963). "Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 20 (2): 130–141. Bibcode:1963JAtS...20..130L. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1963)020<0130:DNF>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Elaydi, Saber N. (1999). Discrete Chaos. Chapman & Hall/CRC. p. 117.

- ^ Ruelle, David (1991). Chance and Chaos. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Wolfram, Stephen (2002). A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media.

- ^ von Kármán, Theodore (1963). Aerodynamics. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0070676022.. Dover (1994): ISBN 978-0486434858.

- ^ Lewalle, Jacques (2006). "Flow Separation and Secondary Flow: Section 9.1" (PDF). Lecture Notes in Incompressible Fluid Dynamics: Phenomenology, Concepts and Analytical Tools. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2011..

- ^ French, A. P. (1971). Vibrations and Waves. Nelson Thornes.

- ^ Tolman, H. L. (2008). "Practical wind wave modeling" (PDF). In Mahmood, M.F. (ed.). CBMS Conference Proceedings on Water Waves: Theory and Experiment. Howard University, USA, 13–18 May 2008. World Scientific Publications.

- ^ "Types of Dunes". USGS. 29 October 1997. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ Strahler, A.; Archibold, O. W. (2008). Physical Geography: Science and Systems of the Human Environment (4th ed.). John Wiley. p. 442.

- ^ Schwämmle, V.; Herrman, H. J. (11 December 2003). "Solitary wave behaviour of sand dunes". Nature. 426 (6967): 619–620. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..619S. doi:10.1038/426619a. PMID 14668849. S2CID 688445.

- ^ Ball 2009a, p. 68.

- ^ Almgren, Frederick J. Jr.; Taylor, Jean E. (July 1976). "The geometry of soap films and soap bubbles". Scientific American. 235 (235): 82–93. Bibcode:1976SciAm.235a..82A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0776-82.

- ^ Ball 2009a, pp. 96–101.

- ^ Brodie, Christina (February 2005). "Geometry and Pattern in Nature 3: The holes in radiolarian and diatom tests". Microscopy-UK. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Ball 2009a, pp. 51–54.

- ^ Armstrong, M.A. (1988). Groups and Symmetry. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ Hook, J. R.; Hall, H. E. Solid State Physics (2nd Edition). Manchester Physics Series, John Wiley & Sons, 2010. ISBN 978-0-471-92804-1

- ^ Stevens 1974, p. 207.

- ^ Stevens 1974, p. 208.

- ^ a b Ball 2009a, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Murray, James D. (9 March 2013). Mathematical Biology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 436–450. ISBN 978-3-662-08539-4.

- ^ a b Ball 2009a, pp. 159–167.

- ^ Ball 2009a, pp. 168–180.

- ^ Rothenberg 2011, pp. 93–95.

- ^ a b Prum, Richard O.; Williamson, Scott (2002). "Reaction–diffusion models of within-feather pigmentation patterning" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 269 (1493): 781–792. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1896. PMC 1690965. PMID 11958709.

- ^ a b Tongway, D. J.; Valentin, C.; Seghieri, J. (2001). Banded vegetation patterning in arid and semiarid environments. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ a b D'Avanzo, C. (22 February 2004). "Fir Waves: Regeneration in New England Conifer Forests". TIEE. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Morelle, Rebecca (2013-12-09). "'Digital gophers' solve Mima mound mystery". BBC News. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Sample, Ian (18 January 2017). "The secret of Namibia's 'fairy circles' may be explained at last". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "Permafrost: Patterned Ground". US Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on 7 March 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Ghose, Tia. "Human Brain's Bizarre Folding Pattern Re-Created in a Vat". Scientific American. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Tallinen, Tuoma; Chung, Jun Young; Biggins, John S.; Mahadevan, L. (2014). "Gyrification from constrained cortical expansion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (35): 12667–12672. arXiv:1503.03853. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11112667T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1406015111. PMC 4156754. PMID 25136099.

Bibliography

[edit]Pioneering authors

- Fibonacci, Leonardo. Liber Abaci, 1202.

- ———— translated by Sigler, Laurence E. Fibonacci's Liber Abaci. Springer, 2002.

- Haeckel, Ernst. Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms in Nature), 1899–1904.

- Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth. On Growth and Form. Cambridge, 1917.

General books

- Adam, John A. Mathematics in Nature: Modeling Patterns in the Natural World. Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Ball, Philip (2009a). Nature's Patterns: a tapestry in three parts. 1: Shapes. Oxford University Press.

- Ball, Philip (2009b). Nature's Patterns: a tapestry in three parts. 2: Flow. Oxford University Press.

- Ball, Philip (2009c). Nature's Patterns: a tapestry in three parts. 3. Branches. Oxford University Press.

- Ball, Philip. Patterns in Nature. Chicago, 2016.

- Murphy, Pat and Neill, William. By Nature's Design. Chronicle Books, 1993.

- Rothenberg, David (2011). Survival of the Beautiful: Art, Science and Evolution. Bloomsbury Press.

- Stevens, Peter S. (1974). Patterns in Nature. Little, Brown & Co.

- Stewart, Ian (2001). What Shape is a Snowflake? Magical Numbers in Nature. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Patterns from nature (as art)

- Edmaier, Bernard. Patterns of the Earth. Phaidon Press, 2007.

- Macnab, Maggie. Design by Nature: Using Universal Forms and Principles in Design. New Riders, 2012.

- Nakamura, Shigeki. Pattern Sourcebook: 250 Patterns Inspired by Nature.. Books 1 and 2. Rockport, 2009.

- O'Neill, Polly. Surfaces and Textures: A Visual Sourcebook. Black, 2008.

- Porter, Eliot, and Gleick, James. Nature's Chaos. Viking Penguin, 1990.