Glossy ibis

| Glossy ibis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Breeding plumage | |

| |

| Non-breeding plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Threskiornithidae |

| Genus: | Plegadis |

| Species: | P. falcinellus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Plegadis falcinellus (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| |

| Geographical distribution. Breeding Migration Year-round Nonbreeding

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The glossy ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) is a water bird in the order Pelecaniformes and the ibis and spoonbill family Threskiornithidae. The scientific name derives from Ancient Greek plegados and Latin, falcis, both meaning "sickle" and referring to the distinctive shape of the bill.[2]

Distribution

[edit]This is the most widespread ibis species, breeding in scattered sites in warm regions of Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Atlantic and Caribbean regions of the Americas.[3][4] It is thought to have originated in the Old World and spread naturally from Africa to northern South America in the 19th century, from where it spread to North America.[5] The glossy ibis was first documented in the New World in 1817 (New Jersey). Audubon saw the species just once in Florida in 1832. It expanded its range substantially northwards in the 1940s and to the west in the 1980s.[5] This species is migratory; most European birds winter in Africa, and in North America birds from north of the Carolinas winter farther south.[6] Though generally suspected to be a migratory species in India, the glossy ibis is resident in western India.[7] Birds from other populations may disperse widely outside the breeding season. It is increasing in Europe.[1] It disappeared as a regular breeding bird in Spain in the early 20th century, but re-established itself in 1993 and has since rapidly increased with thousands of pairs in several colonies.[8] It has also established rapidly increasing breeding colonies in France, a country with very few breeding records before the 2000s.[9] An increasing number of non-breeding visitors are seen in northwestern Europe, a region where glossy ibis records historically were very rare.[10] For example, there appears to be a growing trend for birds to winter in Britain and Ireland, with at least 22 sightings in 2010.[11] In 2014, a pair attempted to breed in Lincolnshire, the first such attempt in Britain.[12] The first successful breeding in Britain was a pair which fledged one young in Cambridgeshire in 2022.[13] A few birds now spend most summers in Ireland, but there is no present evidence of breeding. In New Zealand, a few birds arrive there annually, mostly in the month of July; recently a pair bred amongst a colony of royal spoonbill.[14] Glossy ibis have been a breeding species in Australia since the 1930s.[15] In India, they are now a breeding species with colonies now seen in agricultural areas, in forested areas with bamboo thickets and breeding alongside other colonially nesting waterbirds.[16][17] Year-long studies have also shown Glossy ibises to be foraging in agricultural wetlands and flooded farmlands in western India.[7]

Behaviour

[edit]Glossy ibises undertake dispersal movements after breeding and are highly nomadic. The more northerly populations are fully migratory and travel on a broad front, for example across the Sahara Desert. Glossy ibis ringed in the Black Sea seem to prefer the Sahel and West Africa to winter, those ringed in the Caspian Sea have been found to move to East Africa, the Arabian peninsula and as far east as Pakistan and India.[18] Numbers of glossy ibis in western India varied dramatically seasonally with the highest numbers being seen in the winter and summers, and drastically declining in the monsoon likely indicating local movements to a suitable area to breed.[7] Populations in temperate regions breed during the local spring, while tropical populations nest to coincide with the rainy season. Nesting is often in mixed-species colonies. When not nesting, flocks of over 100 individuals may occur on migration, and during the winter or dry seasons the species is usually found foraging in small flocks. Glossy ibises often roost communally at night in large flocks, with other species, occasionally in trees which can be some distance from wetland feeding areas.

Habitat

[edit]Glossy ibises feed in very shallow water and nest in freshwater or brackish wetlands with tall dense stands of emergent vegetation such as reeds, papyrus (or rushes) and low trees or bushes. They show a preference for marshes at the margins of lakes and rivers but can also be found at lagoons, flood-plains, wet meadows, swamps, reservoirs, sewage ponds, paddies and irrigated farmland. When using farmlands in western India, glossy ibis exhibited strong scale-dependent use of the landscape seasonally. They preferred using areas with >200 ha of wetlands during the summer, and using areas that had intermediate amounts of wetlands (50-100 ha) in the other seasons, though did not necessarily forage in the wetlands.[7] It is less commonly found in coastal locations such as estuaries, deltas, salt marshes and coastal lagoons. Preferred roosting sites are normally in large trees which may be distant from the feeding areas. When human persecution is absent they roost in cities, even using trees beside busy highways and other roads.[19]

Breeding

[edit]

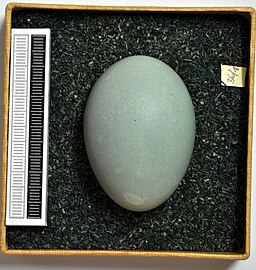

The nest is usually a platform of twigs and vegetation positioned at least 1 m (3.3 ft) above water, sometimes up to 7 m (23 ft) high, in dense stands of emergent vegetation, low trees, or bushes. 3 to 4 eggs (occasionally 5) are laid, and are incubated by both male and female birds for between 20 and 23 days. The young can leave the nest after about 7 days, but the parents continue to feed them for another 6 or 7 weeks. The young fledge in about 28 days.[1]

Diet

[edit]The diet of the glossy ibis is variable according to the season and is very dependent on what is available. Prey includes adult and larval insects such as aquatic beetles, dragonflies, damselflies, grasshoppers, crickets, flies and caddisflies, Annelida including leeches, molluscs (e.g. snails and mussels), crustaceans (e.g. crabs and crayfish) and occasionally fish, amphibians, lizards, small snakes and nestling birds.[1]

Description

[edit]This species is a mid-sized ibis. It is 48–66 cm (19–26 in) long, averaging around 59.4 cm (23.4 in) with an 80–105 cm (31–41 in) wingspan.[20][21] The culmen measures 9.7 to 14.4 cm (3.8 to 5.7 in) in length, each wing measures 24.8–30.6 cm (9.8–12.0 in), the tail is 9–11.2 cm (3.5–4.4 in) and the tarsus measures 6.8–11.3 cm (2.7–4.4 in).[21] The body mass of this ibis can range from 485 to 970 g (1.069 to 2.138 lb).[21] Breeding adults have reddish-brown bodies and shiny bottle-green wings. Non-breeders and juveniles have duller bodies. This species has a brownish bill, dark facial skin bordered above and below in blue-gray (non-breeding) to cobalt blue (breeding), and red-brown legs. Unlike herons, ibises fly with necks outstretched, their flight being graceful and often in V formation. It also has shiny feathers.

Sounds made by this rather quiet ibis include a variety of croaks and grunts, including a hoarse grrrr made when breeding.

Gallery

[edit]-

In flight, Huelva, Spain

-

Glossy Ibis, John J. Audubon, Brooklyn Museum

-

Egg, Collection Museum Wiesbaden

-

In Victoria, Australia

-

In Borit, Gojal, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

Conservation

[edit]The glossy ibis is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies. Glossy ibises can be threatened by wetland habitat degradation and loss through drainage, increased salinity, groundwater extraction and invasion by exotic plants.[1]

The common name black curlew may be a reference to the glossy ibis and this name appears in Anglo-Saxon literature.[22] Yalden and Albarella do not mention this species as occurring in medieval England.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e BirdLife International (2019) [amended version of 2016 assessment]. "Plegadis falcinellus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T22697422A155528413. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22697422A155528413.en. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 157, 310. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Olson, S.L.; James, H.F.; Meister, C.A. (1981). "Winter field notes and specimen weights of Cayman Island birds". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 101: 339–346. ISSN 0007-1595.

Wetmore observed an adult and an immature with herons in the West Bay district, 3 February 1972. Johnston et al. (1971) list but one sighting on GC (Grand Cayman) and 2 on CB (Cayman Brac).

- ^ Santoro, Simone; Sundar, K.S.G.; Cano-Alonso, L.S. (2019). "Glossy Ibis ecology and conservation". SIS Conservation. 1: 1–148. ISBN 978-2-491451-01-1.

- ^ a b Patten, Michael A.; Lasley, Greg W. "Range Expansion of the Glossy Ibis in North America" (PDF). North American Birds. 54 (3): 241–247.

- ^ Taft, Dave (28 June 2013). "Glossy Ibises Are Like 21st-Century Pterodactyls". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d Sundar, K.S.G.; Kittur, S. (2019). "Glossy Ibis Distribution and Abundance in an Indian Agricultural Landscape: Seasonal and Annual Variations" (PDF). SIS Conservation. 1: 135–138.

- ^ Máñez, M.; et al. (2019). "Twenty two years of monitoring of the Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus in Doñana". SIS Conservation. 2019: 98–103.

- ^ Champagnon, J.; et al. (2019). "The Settlement of Glossy Ibis in France". SIS Conservation. 2019: 50–55.

- ^ "Rykind af sorte ibisser i danske vådområder" (in Danish). Danish Ornithological Society. 20 May 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Hudson N. & the Rarities Committee (2010). "Report on Rare Birds in Great Britain". British Birds. 104: 557–629.

- ^ "Glossy ibis in nest attempt at Frampton Marshes". BBC News. 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Glossy Ibis breeds in Britain for first time". BirdGuides. 13 September 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ "Glossy ibis Plegadis falcinellus (Linnaeus, 1766)". New Zealand Birds Online. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Bailey, R. F. (1934). "New Nesting Records of Glossy Ibis". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 33 (4): 279–291. Bibcode:1934EmuAO..33..279B. doi:10.1071/MU933279. ISSN 0158-4197.

- ^ Tiwari, J. K.; Rahmani, A. R. (1998). "Large heronries in Kutch and the nesting of Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus at Luna jheel, Kutch, Gujarat, India". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 95: 67–70.

- ^ Ranade, Sachin; Ranade, Sonali; Banajyoti, Nath; Saikia, Prasanta Kumar; Prakash, Vibhu (2021). "Recent breeding record and parental care behaviour of Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus in the Assam state, India" (PDF). SIS Conservation. 3: 13–18.

- ^ Santoro, S.; Champagnon, J.; Kharitonov, S.P.; Zwarts, L.; Oschadleus, H.D.; Manez, M.; Samraoui, B.; Nedjah, R.; Volponi, S.; Cano-Alonso, L.S. (2019). "Long-distance Dispersal of the Afro-Eurasian Glossy Ibis From Ring Recoveries" (PDF). SIS Conservation. 1: 139–146.

- ^ Mehta, Kanishka; Koli, Vijay K.; Kittur, Swati; Gopi Sundar, K. S. (2024). "Can you nest where you roost? Waterbirds use different sites but similar cues to locate roosting and breeding sites in a small Indian city". Urban Ecosystems. 27 (4): 1279–1290. Bibcode:2024UrbEc..27.1279M. doi:10.1007/s11252-023-01454-5. ISSN 1573-1642.

- ^ "Glossy ibis videos, photos and facts – Plegadis falcinellus". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2013-03-27. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Hancock, James A.; Kushan, James A.; Kahl, M. Philip (1992). Storks, Ibises, and Spoonbills of the World. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-322730-0.

- ^ "Definition of black curlew". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Yalden, D.W.; Albarella, U. (2009). The History of British Birds. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958116-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Cramp, Stanley; Perrins, C.M.; Brooks, Duncan J., eds. (1994). Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa: The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198546795.

- Field Guide to the Birds of North America (4th ed.). National Geographic Society.

External links

[edit]- BirdLife species factsheet for Plegadis falcinellus

- Glossy Ibis - The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Glossy Ibis Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- "Glossy Ibis media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus - eNature.com

- Field guide photo page on Flickr

- Glossy ibis photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Plegadis falcinellus at IUCN Red List maps

- http://bo.adu.org.za/pdf/BO_2016_07-101.pdf