National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012

The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2012[1][2] (Pub. L. 112–81 (text) (PDF)) is a United States federal law which, among other things, specified the budget and expenditures of the United States Department of Defense. The bill passed the U.S. House on December 14, 2011 and passed the U.S. Senate on December 15, 2011. It was signed into law on December 31, 2011 by President Barack Obama.[3]

In a signing statement, President Obama described the Act as addressing national security programs, Department of Defense health care costs, counter-terrorism within the United States and abroad, and military modernization.[4][5] The Act also imposed new economic sanctions against Iran (section 1245), commissioned appraisals of the military capabilities of countries such as Iran, China, and Russia,[6] and refocused the strategic goals of NATO towards "energy security".[7] The Act increased pay for military service members[8] and gave governors the ability to request the help of military reservists in the event of a hurricane, earthquake, flood, terrorist attack, or other disaster.[9]

The Act contains controversial language allowing the indefinite military detention of persons the government suspects of involvement in terrorism, including U.S. citizens arrested on American soil. Although the White House[10] and Senate sponsors[11] of the Act maintained that the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) already allowed indefinite detention, the Act "affirms" this authority and makes specific provisions as to its exercise.[12][13] The detention provisions of the Act have received critical attention from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Bill of Rights Defense Committee, and media sources which are concerned about the scope of the President's authority.[14][15][16][17] The detention powers contained within the Act face legal challenge.

Section 818

[edit]This section contains "critical provisions"[18] reflecting a bipartisan amendment regarding counterfeit electronic parts in the Defense Department's supply chain,[1]: Section 818 adopted following concerns raised by Senators Carl Levin and John McCain, chairman and ranking member respectively of the Senate Committee on Armed Services, regarding counterfeit electronic parts highlighted in an investigation commenced in March 2011,[19] which found that 1,800 cases of suspected counterfeit components were in use within over 1 million individual products".[20] Further year-long work undertaken by the Senate Committee and contained in a report on counterfeit parts in the Department of Defense supply chain released on 12 May 2012 showed that counterfeit electronic parts of Chinese origin had been found in the Air Force's C-130J and C-27J cargo planes, in assemblies used in the Navy's SH-60B helicopter, and in the Navy's P-8A surveillance plane, among 1800 cases identified.[21]

Detention without trial: Section 1021

[edit]The detention sections of the NDAA begin by "affirm[ing]" that the authority of the President under the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists (AUMF), a joint resolution passed in the immediate aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks, includes the power to detain, via the Armed Forces, any person, including a U.S. citizen,[11][22] "who was part of or substantially supported al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or associated forces that are engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners", and anyone who commits a "belligerent act" against the United States or its coalition allies in aid of such enemy forces, under the law of war, "without trial, until the end of the hostilities authorized by the [AUMF]". The text authorizes trial by military tribunal, or "transfer to the custody or control of the person's country of origin", or transfer to "any other foreign country, or any other foreign entity".[23]

Addressing previous conflicts with the Obama Administration regarding the wording of the Senate text, the Senate–House compromise text, in sub-section 1021(d), also affirms that nothing in the Act "is intended to limit or expand the authority of the President or the scope of the Authorization for Use of Military Force". The final version of the bill also provides, in sub-section(e), that "Nothing in this section shall be construed to affect existing law or authorities relating to the detention of United States citizens, lawful resident aliens of the United States, or any other persons who are captured or arrested in the United States". As reflected in Senate debate over the bill, there is a great deal of controversy over the status of existing law.[14]

An amendment to the Act that would have replaced current text with a requirement for executive clarification of detention authorities was rejected by the Senate.[24] According to Senator Carl Levin, "the language which precluded the application of section 1031 to American Citizens was in the bill that we originally approved in the Armed Services Committee and the Administration asked us to remove the language which says that U.S. citizens and lawful residents would not be subject to this section".[25] The Senator refers to section 1021 as "1031" because it was section 1031 at the time of his speaking.

Requirement for military custody: Section 1022

[edit]

All persons arrested and detained according to the provisions of section 1021, including those detained on U.S. soil, whether detained indefinitely or not, are required to be held by the United States Armed Forces. The law affords the option to have U.S. citizens detained by the armed forces but this requirement does not extend to them, as with foreign persons. Lawful resident aliens may or may not be required to be detained by the Armed Forces, "on the basis of conduct taking place within the United States".[26][27]

During debate on the senate floor, Levin stated that "Administration officials reviewed the draft language for this provision and recommended additional changes. We were able to accommodate those recommendations, except for the Administration request that the provision apply only to detainees captured overseas and there's a good reason for that. Even here, the difference is modest, because the provision already excludes all U.S. citizens. It also excludes lawful residents of United States, except to extent permitted by the constitution. The only covered persons left are those who are illegally in this country or on a tourist visa or other short-term basis. Contrary to some press statements, the detainee provisions in our bill do not include new authority for the permanent detention of suspected terrorists. Rather, the bill uses language provided by the Administration to codify existing authority that has been upheld in federal courts".[28]

A Presidential Policy Directive entitled "Requirements of the National Defense Authorization Act"[29][30] regarding the procedures for implementing §1022 of the NDAA was issued on February 28, 2012, by the White House.[31][32] The directive consists of eleven pages of specific implementation procedures including defining scope and limitations. Judge Kathrine B. Forrest wrote in Hedges v. Obama: "That directive provides specific guidance as to the 'Scope of Procedures and Standard for Covered Persons Determinations.' Specifically, it states that 'covered persons' applies only to a person who is not a citizen of the United States and who is a member or part of al-Qaeda or an associated force that acts in coordination with or pursuant to the direction of al-Qaeda; and "who participated in the course of planning or carrying out an attack or attempted attack against the United States or its coalition partners" (see p. 11–12).[33] Under procedures released by the White House the military custody requirement can be waived in a wide variety of cases.[31] Among the waiver possibilities are the following:[34]

- The suspect's home country objects to military custody

- The suspect is arrested for conduct conducted in the United States

- The suspect is originally charged with a non-terrorism offense

- The suspect was originally arrested by state or local law enforcement

- A transfer to military custody could interfere with efforts to secure cooperation or confession

- A transfer would interfere with a joint trial

Actions from the White House and Senate leading to the vote

[edit]The White House threatened to veto the Senate version of the Act,[10] arguing in an executive statement on November 17, 2011, that while "the authorities granted by the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists, including the detention authority ... are essential to our ability to protect the American people ... (and) Because the authorities codified in this section already exist, the Administration does not believe codification is necessary and poses some risk".

The statement furthermore objected to the mandate for "military custody for a certain class of terrorism suspects", which it called inconsistent with "the fundamental American principle that our military does not patrol our streets".[10] The White House may now waive the requirement for military custody for some detainees following a review by appointed officials including the Attorney General, the secretaries of state, defense and homeland security, the chairman of the military's Joint Chiefs of Staff and the director of national intelligence.[35]

During debate within the Senate and before the Act's passage, Senator Mark Udall introduced an amendment interpreted by the ACLU[36] and some news sources[37] as an effort to limit military detention of American citizens indefinitely and without trial. The amendment proposed to strike the section "Detainee Matters" from the bill, and replace section 1021 (then titled 1031) with a provision requiring the Administration to clarify the Executive's authority to detain suspects on the basis of the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists.[38] The amendment was rejected by a vote of 60–38 (with 2 abstaining).[39] Udall subsequently voted for the Act in the joint session of Congress that passed it, and though he remained "extremely troubled" by the detainee provisions, he promised to "push Congress to conduct the maximum amount of oversight possible".[37]

The Senate later adopted by a 98 to 1 vote a compromise amendment, based upon a proposal by Senator Dianne Feinstein, which preserves current law concerning U.S. citizens and lawful resident aliens detained within the United States.[40] After a Senate–House compromise text explicitly ruled out any limitation of the President's authorities, but also removed the requirement of military detention for terrorism suspects arrested in the United States, the White House issued a statement saying that it would not veto the bill.[41]

In his Signing Statement, President Obama explained: "I have signed the Act chiefly because it authorizes funding for the defense of the United States and its interests abroad, crucial services for service members and their families, and vital national security programs that must be renewed ... I have signed this bill despite having serious reservations with certain provisions that regulate the detention, interrogation, and prosecution of suspected terrorists".[42]

The vote

[edit]

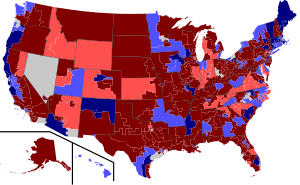

On December 14, 2011, the bill passed the U.S. House by a vote of 283 to 136, with 19 representatives not voting,[43] and passed by the U.S. Senate on December 15, 2011, by a vote of 86 to 13.[44]

Controversy over indefinite detention

[edit]

House vote by congressional district.[45]

Senate vote by state.[46]

Section 1021. ... Congress affirms that the authority of the President to use all necessary and appropriate force pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force ... includes the authority for the Armed Forces of the United States to detain covered persons (as defined in subsection (b)) pending disposition under the law of war. ... Section 1022. . ... Except as provided in paragraph (4), the Armed Forces of the United States shall hold a person described in paragraph (2) who is captured in the course of hostilities authorized by the Authorization for Use of Military Force ... in military custody pending disposition under the law of war.

American and international reactions

[edit]Section 1021 and 1022 have been called a violation of constitutional principles and of the Bill of Rights.[48] Internationally, the UK-based newspaper The Guardian has described the legislation as allowing indefinite detention "without trial [of] American terrorism suspects arrested on U.S. soil who could then be shipped to Guantánamo Bay;"[49] Al Jazeera has written that the Act "gives the U.S. military the option to detain U.S. citizens suspected of participating or aiding in terrorist activities without a trial, indefinitely".[50] The official Russian international radio broadcasting service Voice of Russia has been highly critical of the legislation, writing that under its authority "the U.S. military will have the power to detain Americans suspected of involvement in terrorism without charge or trial and imprison them for an indefinite period of time"; it has furthermore written that "the most radical analysts are comparing the new law to the edicts of the 'Third Reich' or 'Muslim tyrannies'".[51] The Act was strongly opposed by the ACLU, Amnesty International, Human Rights First, Human Rights Watch, The Center for Constitutional Rights, the Cato Institute, Reason Magazine, and The Council on American-Islamic Relations, and was criticized in editorials published in the New York Times[52] and other news organizations.[53]

Americans have sought resistance of the NDAA through successful resolution campaigns in various states and municipalities. The states of Rhode Island and Michigan, the Colorado counties of Wade, El Paso, and Fremont, as well as the municipalities of Northampton, MA. and Fairfax, CA, have all passed resolutions rejecting the indefinite detention provisions of the NDAA.[54] The Bill of Rights Defense Committee has launched a national campaign to mobilize individuals at the grassroots level to pass local and state resolutions voicing opposition to the NDAA. Campaigns have begun to grow in New York City, Miami and San Diego, among other cities and states.[55]

Attorneys Carl J. Mayer and Bruce I. Afran filed a complaint January 13, 2012, in the Southern U.S. District Court in New York City on the behalf of Chris Hedges against Barack Obama and Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta to challenge the legality of the Authorization for Use of Military Force as embedded in the latest version of the National Defense Authorization Act, signed by the president December 31.[56] Lt. Col. Barry Wingard, a military attorney representing prisoners at Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp, noted that under the NDAA "an American citizen can be detained forever without trial, while the allegations against you go uncontested because you have no right to see them".[57]

Views of the Obama Administration

[edit]On December 31, 2011, and after signing the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 into law, President Obama issued a statement on it addressing "certain provisions that regulate the detention, interrogation, and prosecution of terrorism suspects". In the statement the President maintains that "the legislation does nothing more than confirm authorities that the Federal courts have recognized as lawful under the 2001 AUMF". The statement also maintains that the "Administration will not authorize the indefinite military detention without trial of American citizens", and that it "will interpret section 1021 in a manner that ensures that any detention it authorizes complies with the Constitution, the laws of war, and all other applicable law". Referring to the applicability of civilian versus military detention, the statement argued that "the only responsible way to combat the threat al-Qa'ida poses is to remain relentlessly practical, guided by the factual and legal complexities of each case and the relative strengths and weaknesses of each system. Otherwise, investigations could be compromised, our authorities to hold dangerous individuals could be jeopardized, and intelligence could be lost".[58]

On February 22, 2012, the Administration represented by Jeh Charles Johnson, General Counsel of the U.S. Department of Defense defined the term "associated forces". Johnson stated in a speech at Yale Law School:

An "associated force," as we interpret the phrase, has two characteristics to it: (1) an organized, armed group that has entered the fight alongside al Qaeda, and (2) is a co-belligerent with al Qaeda in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners. In other words, the group must not only be aligned with al Qaeda. It must have also entered the fight against the United States or its coalition partners. Thus, an "associated force" is not any terrorist group in the world that merely embraces the al Qaeda ideology.[59]

On February 28, 2012, the administration announced that it would waive the requirement for military detention in "any case in which officials [believe] that placing a detainee in military custody could impede counterterrorism cooperation with the detainee's home government or interfere with efforts to secure the person's cooperation or confession".[35] Application of military custody to any suspect is determined by a national security team including the attorney general, the secretaries of state, defense, and homeland security, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Director of National Intelligence.[35]

On September 12, 2012, U.S. District Judge Katherine B. Forrest issued an injunction against the indefinite detention provisions of the NDAA (section 1021(b)(2)) on the grounds of unconstitutionality; however, this injunction was appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit the following day and was later reversed.[60][61]

The Administration explained on November 6, 2012, the terms "substantially supported" and "associated forces" in its opening brief before the U.S. Second Court of Appeals in Hedges v. Obama.[62] With respect to the term "substantially supported" the Obama administration stated:

The term "substantial support" covers support that, in analogous circumstances in a traditional international armed conflict, is sufficient to justify detention. The term thus encompasses individuals who, even if not considered part of the irregular enemy forces at issue in the current conflict, bear sufficiently close ties to those forces and provide them support that warrants their detention in prosecution of the conflict. See, e.g., Geneva Convention III, Art. 4.A(4) (encompassing detention of individuals who "accompany the armed forces without actually being members thereof, such as civilian members of military aircraft crews, war correspondents, supply contractors, members of labour units or of services responsible for the welfare of the armed forces, provided that they have received authorization from the armed forces which they accompany"); Int'l Comm. Of the Red Cross Commentary on Third Geneva Convention 64 (Pictet, ed. 1960) (Art. 4(a)(4) intended to encompass certain "classes of persons who were more or less part of the armed force" while not members thereof); see also, e.g., Gov't Br. in Al Bihani v. Obama, No. 99-5051, 2009 WL 2957826, at 41–42 (D.C. Cir. Sept. 15, 2009) (explaining that petitioner "was unequivocally part of" an enemy force, but even if he "was not part of enemy forces, he accompanied those forces on the battlefield and performed services (e.g. cooking, guard duty)" for them that justified military detention). Under those principles, the term "substantially support" cannot give rise to any reasonable fear that it will be applied to the types of independent journalism or advocacy at issue here. See March 2009 Mem. at 2 ("substantially support" does not include those who provide "unwitting or insignificant support" to al-Qaeda); cf. Bensayah, 610 F.3d at 722, 725 ("purely independent conduct of a freelancer is not enough"). ... the "substantial support" prong addresses actions like "plan[ning] to take up arms against the United States" on behalf of al-Qaeda and "facilitat[ing] the travel of unnamed others to do the same." Page 35-37, 61 in[62]

And with respect to the term "associated forces", the Administration cited the above-mentioned Jeh Johnson's remarks on February 22, 2012:

That term [associated forces] is well understood to cover cobelligerent groups that fight together with al-Qaeda or Taliban forces in the armed conflict against the United States or its coalition partners. ... after carefully considering how traditional law-of-war concepts apply in this armed conflict against non-state armed groups, the government has made clear that an "'associated force' ... has two characteristics": (1) an organized, armed group that has entered the fight alongside al Qaeda, [that] (2) is a co-belligerent with al Qaeda in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners.[62]

The Administration summarized later in its brief that:

an associated force is an "organized, armed group that has entered the fight alongside al Qaeda" or the Taliban and is "a cobelligerent with al Qaeda [or the Taliban] in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners." Page 60-61 in[62]

NBC News released in February 2014 an undated U.S. Department of Justice White paper entitled "Lawfulness of a Lethal Operation Directed Against a U.S. Citizen who is a Senior Operational Leader of Al Qa'ida or An Associated Force."[63] In it the Justice Department stated with respect to the term "associated forces"

An associated force of al-Qa'ida includes a group that would qualify as a co-belligerent under the laws of war. See Hamily v. Obama, 616 F. Supp. 2d 63, 74–75 (D.D.C. 2009) (authority to detain extends to "associated forces," which "mean 'co-belligerents' as that term is understood under the laws of war"). (Footnote at page 1 in[64]

Legal arguments that the legislation does not allow the indefinite detention of U.S. citizens

[edit]Mother Jones wrote that the Act "is the first concrete gesture Congress has made towards turning the homeland into the battlefield", arguing that "codifying indefinite detention on American soil is a very dangerous step". The magazine has nevertheless contested claims by The Guardian and the New York Times that the Act "allows the military to indefinitely detain without trial American terrorism suspects arrested on U.S. soil who could then be shipped to Guantánamo Bay", writing that "they're simply wrong ... It allows people who think the 2001 Authorization to Use Military Force against the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks gives the president the authority to detain U.S. citizens without charge or trial to say that, but it also allows people who can read the Constitution of the United States to argue something else".[65] Legal commentator Joanne Mariner has noted in Verdict that the scope of existing detention power under the AUMF is "subject to vociferous debate and continuing litigation".[66] In the years that followed the September 11 attacks, the AUMF was interpreted to allow the indefinite detention of both citizens and non-citizens arrested far from any traditional battlefield, including in the United States.[citation needed]

Other legal commentators argue that the NDAA does not permit truly "indefinite" detention, given that the period of detention is limited by the duration of the armed conflict. In making this claim, they emphasize the difference between (1) detention pursuant to the "laws of war" and (2) detention pursuant to domestic criminal law authorities.[67] David B. Rivkin and Lee Casey, for example, argue that detention under the AUMF is authorized under the laws of war and is not indefinite because the authority to detain ends with the cessation of hostilities. They argue that the NDAA invokes "existing Supreme Court precedent ... that clearly permits the military detention (and even trial) of citizens who have themselves engaged in hostile acts or have supported such acts to the extent that they are properly classified as 'combatants' or 'belligerents'". This reflects the fact that, in their view, the United States is, pursuant to the AUMF, at war with al-Qaeda, and detention of enemy combatants in accordance with the laws of war is authorized. In their view, this does not preclude trial in civilian courts, but it does not require that the detainee be charged and tried. If the detainee is an enemy combatant who has not violated the laws of war, he is not chargeable with any triable offense. Commentators who share this view emphasize the need not to blur the distinction between domestic criminal law and the laws of war.[67][68]

Legal arguments that the legislation allows indefinite detention

[edit]The American Civil Liberties Union has stated that "While President Obama issued a signing statement saying he had 'serious reservations' about the provisions, the statement only applies to how his administration would use the authorities granted by the NDAA", and, despite claims to the contrary, "The statute contains a sweeping worldwide indefinite detention provision ... [without] temporal or geographic limitations, and can be used by this and future presidents to militarily detain people captured far from any battlefield". The ACLU also maintains that "the breadth of the NDAA's detention authority violates international law because it is not limited to people captured in the context of an actual armed conflict as required by the laws of war".[69]

Proposed legislative reforms

[edit]Following the passage of the NDAA, various proposals have been offered to clarify the detainee provisions. One example, H.R. 3676, sponsored by U.S. Representative Jeff Landry of Louisiana, would amend the NDAA "to specify that no U.S. citizen may be detained against his or her will without all the rights of due process".[70] Other similar bills in the U.S. House of Representatives have been introduced by Representatives John Garamendi of California and Chris Gibson of New York.

The Feinstein-Lee Amendment that would have explicitly barred the military from holding American citizens and permanent residents in indefinite detention without trial as terrorism suspects was dropped on December 18, 2012, during the merging of the House and Senate versions of the 2013 National Defense Authorization Act.[71][72][73]

Legal challenges to indefinite detention

[edit]Hedges v. Obama

[edit]A lawsuit was filed January 13, 2012, against the Obama Administration and Members of the U.S. Congress by a group including former New York Times reporter Christopher Hedges challenging the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012.[60] The plaintiffs contend that Section 1021(b)(2) of the law allows the detention of citizens and permanent residents taken into custody in the United States on "suspicion of providing substantial support" to groups engaged in hostilities against the United States such as al-Qaeda and the Taliban.[60]

In May 2012, a federal court in New York issued a preliminary injunction which temporarily blocked the indefinite detention powers of NDAA Section 1021(b)(2) on the grounds of unconstitutionality.[74] On August 6, 2012, federal prosecutors representing President Obama and Defense Secretary Leon Panetta filed a notice of appeal with the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, hoping to eliminate the ban.[75] The following day arguments from both sides were heard by U.S. District Judge Katherine B. Forrest during a hearing to determine whether to make her preliminary injunction permanent or not.[76] On September 12, 2012, Judge Forrest issued a permanent injunction,[77] but this was appealed by the Obama Administration on September 13, 2012.[60][61] A federal appeals court granted a U.S. Justice Department's request for an interim stay of the permanent injunction, pending the Second Circuit's consideration of the government's motion to stay the injunction throughout its appeal.[78][79][80] The court also said that a Second Circuit motions panel will take up the government's motion for stay pending appeal on September 28, 2012.[78][79][80] On October 2, 2012, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the ban on indefinite detention will not go into effect until a decision on the Obama Administration's appeal is rendered.[81] The U.S. Supreme Court refused on December 14, 2012, to lift the stay pending appeal of the order issued by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit on October 2, 2012.[82] The Second Circuit Court of Appeals overturned on July 17, 2013, the district court's ruling which struck down § 1021(b)(2) of NDAA as unconstitutional, because the plaintiffs lacked legal standing to challenge it.[83] The Supreme Court denied certiorari in an order issued April 28, 2014.[84][85] Critics of the decision quickly pointed out that, without the right to a trial, it is impossible for an individual with legal standing to challenge 1021 without having already been released.

States taking action against indefinite detention sections of NDAA

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (August 2023) |

As of April 2013, four states had passed resolutions through committee to adjust or block the detainment provisions of the 2012 NDAA. Anti-NDAA legislation passed the full Indiana Senate by a vote of 31–17.[86][better source needed] An additional 13 states have introduced legislation against the detainment provisions.[87][better source needed]

Counties and municipalities taking action against indefinite detention sections of NDAA

[edit]Nine counties have passed resolutions against sections 1021 and 1022 of the NDAA. They are: Moffat, Weld, and Fremont counties in Colorado; Harper County, Kansas; Allegan and Oakland counties in Michigan; Alleghany County in North Carolina; and Fulton and Elk counties in Pennsylvania.[86] Resolutions have been introduced in three counties: Barber County, Kansas; Montgomery County, Maryland; and Lycoming County, Pennsylvania.[86]

Eleven municipalities have passed resolutions as well. They are: Berkeley, Fairfax, San Francisco, and Santa Cruz, California; Cherokee City, Kansas; Northampton, Massachusetts; Takoma Park, Maryland; Macomb, New York; New Shorehampton, Rhode Island; League City, Texas; and Las Vegas, Nevada (currently waiting on the county to pass a joint resolution).[86] An additional 13 municipalities have introduced anti-NDAA resolutions: San Diego, California; Miami, Florida; Portland, Maine; Chapel Hill, Durham, and Raleigh, North Carolina; Albuquerque, New Mexico; Albany and New York City, New York; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Dallas, Texas; Springfield, Virginia; and Tacoma, Washington.[86]

Northampton, Massachusetts, became the first city in New England to pass a resolution rejecting the NDAA on February 16, 2012.[86] William Newman, Director of the ACLU in western Massachusetts, said, "We have a country based on laws and process and fairness. This law is an absolute affront to those principles that make America a free nation".[88]

Sanctions targeting the Iranian Central Bank

[edit]As part of the ongoing dispute over Iranian uranium enrichment, section 1245 of the NDAA imposes unilateral sanctions against the Central Bank of Iran, effectively blocking Iranian oil exports to countries which do business with the United States.[89][90] The new sanctions impose penalties against entities—including corporations and foreign central banks—which engage in transactions with the Iranian central bank. Sanctions on transactions unrelated to petroleum take effect 60 days after the bill is signed into law, while sanctions on transactions related to petroleum take effect a minimum of six months after the bill's signing.[90] The bill grants the U.S. President authority to grant waivers in cases in which petroleum purchasers are unable, due to supply or cost, to significantly reduce their purchases of Iranian oil, or in which American national security is threatened by implementation of the sanctions.[90][91] Following the signing into law of the NDAA, the Iranian rial fell significantly against the U.S. dollar, reaching a record low two days after the bill's enactment, a change widely attributed to the expected impact of the new sanctions on the Iranian economy.[92][93][94][95] Officials within the Iranian government have threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz, an important passageway for Middle East oil exports, should the United States press forward with the new sanctions as planned.[93][96]

Military pay and benefits

[edit]Amendments made to the bill following its passage include a 1.6 percent pay increase for all service members, and an increase in military healthcare enrollment and copay fees. The changes were unanimously endorsed by the Senate Armed Services Committee.[8]

See also

[edit]- Hedges v. Obama

- Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists

- Enemy Expatriation Act

- Hamdan v. Rumsfeld

- Hamdi v. Rumsfeld

- Marbury v. Madison

- Military Commissions Act of 2006

- National Defense Authorization Act

- Posse Comitatus Act

- Ex parte Quirin

- Smith Act

- Unlawful combatant

- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013

References

[edit]- ^ a b 112th Congress, 1st Session, H1540CR.HSE: "National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012."

- ^ "H.R. 1540 (112th): National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012". govtrack.us. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ Nakamura, David (2 January 2012). "Obama signs defense bill, pledges to maintain legal rights of terror suspects". Washington Post. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ^ “President Obama's signing statement”, "White House Press Office", December 31, 2011

- ^ "Barack Obama: Statement on Signing the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012". John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters, The American Presidency Project [online]. December 31, 2011. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- ^ Sections 1232 and 1240.

- ^ Section 1233 from H1540CR.HSE: "National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012.".

- ^ a b Howell, Terry (20 June 2011). "2012 Defense Act – Pay Increase, Changes to Special Pay and TRICARE". Military.com. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "New US law lets reservists respond to disasters". Fox News. Associated Press. 30 August 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ a b c "STATEMENT OF ADMINISTRATION POLICY" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. 17 November 2011. Retrieved 2011-12-14 – via National Archives.

- ^ a b Knickerbocker, Brad (3 December 2011). "Guantánamo for US citizens? Senate bill raises questions". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ Khalek, Rania, "Global Battlefield' Provision Allowing Indefinite Detention of Citizens Accused of Terror Could Pass This Week", Alternet, December 13, 2011.

- ^ Library of Congress THOMAS. H.R. 1540 – National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2012 Versions of H.R.1540 Archived 2012-12-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Savage, Charlie (December 1, 2011). "Senate Declines to Clarify Rights of American Qaeda Suspects Arrested in U.S." The New York Times.

- ^ Carter, Tom "US Senators back law authorizing indefinite military detention without trial or charge," World Socialist Web Site, December 2, 2011.

- ^ "H.R.1540: National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 – U.S. Congress". OpenCongress. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- ^ "S.1867: National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 – U.S. Congress". OpenCongress. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- ^ Senate Armed Services Committee, Completion of Conference with The House of Representatives on H.R. 1540, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012, published 12 December 2011, accessed 2 January 2022

- ^ Senate Armed Services Committee, Senate Armed Services Committee Announces Investigation into Counterfeit Electronic Parts in DOD Supply Chain, published 9 March 2011, accessed 2 January 2022

- ^ Trace Laboratories, Inc., Counterfeit Electronic Components: Understanding the Risk, accessed 4 January 2022

- ^ Nash-Hoff, M. Senate Report Reveals Extent of Chinese Counterfeit Parts in Defense Industry, published 31 May 2012, accessed 12 March 2022

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (16 December 2012). "Three myths about the detention bill". Salon. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

Section 1021, authorizes indefinite detention for the broad definition of "covered persons" .... And that section does provide that "Nothing in this section shall be construed to affect existing law or authorities relating to the detention of United States citizens, lawful resident aliens of the United States, or any other persons who are captured or arrested in the United States." So that section contains a disclaimer regarding an intention to expand detention powers for U.S. citizens, but does so only for the powers vested by that specific section. More important, the exclusion appears to extend only to U.S. citizens "captured or arrested in the United States" — meaning that the powers of indefinite detention vested by that section apply to U.S. citizens captured anywhere abroad (there is some grammatical vagueness on this point, but at the very least, there is a viable argument that the detention power in this section applies to U.S. citizens captured abroad).

- ^ 112th Congress, 1st Session, H1540CR.HSE: "National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012." pp. 265–266.

- ^ "Senate Poised to Pass Indefinite Detention Without Charge or Trial", American Civil Liberties Union, December 1, 2011.

- ^ Senate Session – C-SPAN Video Library

- ^ McGreal, Chris, "Military given go-ahead to detain US terrorist suspects without trial," The Guardian, 14 December 2011: [1].

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn, "Obama to sign indefinite detention bill into law," Salon.com, 14 December 2011: [2].

- ^ "Senate Session Nov. 17, 2011". C-Span. 17 November 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ "Presidential Policy Directive – Requirements of the National Defense Authorization Act". The White House Office of the Press Secretary. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ "PRESIDENTIAL POLICY DIRECTIVE/PPD-14" (PDF). The White House. justice.gov. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ a b Jeralyn (28 February 2012). "Obama Issues Rules for Determining Civilian vs Military Custody of Detainees". TalkLeft: The Politics Of Crime. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ "FACT SHEET: PROCEDURES IMPLEMENTING SECTION 1022 OF THE NATIONAL DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION ACT FOR FISCAL YEAR 2012" (PDF). whitehouse.gov. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013 – via National Archives.

- ^ Hedges v. Obama, 12-cv-00331 (U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York (Manhattan) May 16, 2012), archived from the original.

- ^ Reilly, Ryan J. (4 January 2013). "NDAA Signed Into Law By Obama Despite Guantanamo Veto Threat, Indefinite Detention Provisions". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Savage, Charlie (February 28, 2012). "Obama Issues Waivers on Military Custody for Terror Suspects". New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ Khaki, Ateqah (November 29, 2011). "Senate Rejects Amendment Banning Indefinite Detention". ACLU Blog of Rights. American Civil Liberties Union.

- ^ a b "Despite concerns, Udall gives nod to Defense Authorization bill." Denver Post, December 15, 2011.

- ^ Udall Amendment Text for SA 1107.

- ^ U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 112th Congress – 1st Session

- ^ Gerstein, Josh, "Senate Votes to Allow Indefinite Detention of Americans." Politico, December 1, 2011.

- ^ "White House issues statement saying it will not veto defense bill". The Washington Post. December 14, 2011. Archived from the original on December 15, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ "Barack Obama: Statement on Signing the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012". Presidency.ucsb.edu. 2011-12-31. Retrieved 2012-02-27.

- ^ "HR".

- ^ "HR".

- ^ On Agreeing to the Amendment: Amendment 29 to H R 4310

- ^ On the Amendment S.Amdt. 3018 to S. 3254 (National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013)

- ^ http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ81/pdf/PLAW-112publ81.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Commentary: trampling the bill of rights in defense's name." The Kansas City Star, 14 December 2011: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-01-06. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ^ McGreal, C., "Military given go-ahead to detain US terrorist suspects without trial", The Guardian, 14 December 2011: [3].

- ^ Parvaz, D., "US lawmakers legalise indefinite detention", Al Jazeera, 16 December 2011: [4].

- ^ Kramnik, Ilya, "New US Defense Act curtails liberties not military spending", Voice of Russia, 28 December 2011.

- ^ Rosenthal, A., "President Obama: Veto the Defense Authorization Act," The New York Times, 30 November 2011: [5].

- ^ Grey, B. and T. Carter, "The Nation and the National Defense Authorization Act", World Socialist Web Site, 27 December 2011: [6].

- ^ "NDAA: Liberty Preservation Act Tracking". Tenth Amendment Center. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ http://constitutioncampaign.org/campaigns/dueprocess/maps.php Archived 2013-03-07 at the Wayback Machine>

- ^ Hedges, Chris (16 January 2012). "Why I'm Suing Barack Obama". Common Dreams. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Thomas, Lillian (30 September 2012). "A military attorney's access to his Guantanamo client eroded". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "Barack Obama: Statement on Signing the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012". John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters, The American Presidency Project [online]. December 31, 2011. Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- ^ Johnson, Jeh Charles (22 February 2012). "Jeh Johnson's Speech on "National Security Law, Lawyers and Lawyering in the Obama Administration" – Dean's Lecture at Yale Law School on February 22, 2012". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d Van Voris, Bob (13 September 2012). "U.S. Appeals Order Blocking U.S. Military Detention Law". Bloomberg. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ a b Katz, Basil (14 September 2012). "REFILE-U.S. calls ruling on military detention law harmful". Reuters. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d Preet Bharara; Benjamin H. Torrance; Christopher B. Harwood; Jeh Charles Johnson; Stuart F. Delery; Beth S. Brinkmann; Robert M. Loeb; August E. Flentje (6 November 2012). "United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Case: 12-3644 Document: 69 11/06/2012 761770 Brief for the Appellants" (PDF). Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ Isikoff, Michael (4 February 2013). "Justice Department memo reveals legal case for drone strikes on Americans". NBC News. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ "Undated memo entitled "Lawfulness of a Lethal Operation Directed Against a U.S. Citizen who is a Senior Operational Leader of Al Qa'ida or An Associated Force." by the U.S. Department of Justice" (PDF). NBC News. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ "The Defense Bill Passed. So What Does It Do?". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- ^ "The NDAA Explained". Verdict. 2 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Rivkin & Casey, Bill's detainee provisions reaffirm the laws of war."

- ^ ICRC official statement: The relevance of IHL in the context of terrorism Archived 2006-11-29 at the Wayback Machine, 21 July 2005

- ^ "President Obama Signs Indefinite Detention Bill Into Law", ACLU, 31 December 2011.

- ^ Library of Congress: Thomas.

- ^ Bell, Zachary (20 December 2012). "NDAA's indefinite detention without trial returns". salon.com. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (18 December 2012). "Congressional Negotiators Drop Ban on Indefinite Detention of Citizens, Aides Say". New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Kelley, Michael (19 December 2012). "Lawyers Fighting NDAA Indefinite Detention Slam Congress' Latest Decision". Business Insider. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Bob Van Voris & Patricia Hurtado (17 May 2012). "Military Detention Law Blocked By New York Judge". Bloomberg. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ "Indefinite Detention Ruling Appealed By Federal Prosecutors". The Huffington Post. Reuters. 6 August 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ Pinto, Nick (7 August 2012). "NDAA Suit Argued In Federal Court Yesterday". The Village Voice Blogs. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ "Judge Permanently Blocks Indefinite Detention Provision in NDAA". Democracy Now. 13 September 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ a b Bennett, Wells C. (18 September 2012). "Stay You, Stay Me: CA2 Enters Interim Stay Order in Hedges". Lawfare: Hard National Security Choices. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ a b Savage, Charlie (17 September 2012). "U.S. Warns Judge's Ruling Impedes Its Detention Powers". New York Times. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ a b Savage, Charlie (18 September 2012). "U.S. Appeals Judge Grants Stay of Ruling on Detention Law". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ Katz, Basil (2 October 2012). "U.S. appeals court to hear military detention case". Reuters. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ Bennett, Wells (13 December 2012). "Hedges Plaintiffs Ask SCOTUS to Vacate CA2 Stay". Lawfare Blog – Hard National Security Choices. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Dolmetsch, Chris (17 July 2013). "Ruling That Struck Down Military Detention Power Rejected". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ "Order List: 572 U. S. 13-758 HEDGES, CHRISTOPHER, ET AL. V. OBAMA, PRES. OF U.S., ET AL. – Certiorari Denied" (PDF). United States Supreme Court. 29 April 2014. p. 7. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ Denniston, Lyle (28 April 2014). "Detention challenge denied". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f http://www.pandaunite.org/resources/anti-ndaa-legislativetracking[permanent dead link] Retrieved 21 May 2013 Pandaunite.org [dead link]

- ^ www.pandaunite.org[permanent dead link] [dead link]

- ^ Northampton "opts out" of federal law | WWLP.com

- ^ MacInnis, Laura & Parisa Hafezi (31 December 2011). "U.S. steps up sanctions as Iran floats nuclear talks". Reuters Canada. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ^ a b c Lee, Carol E. & Keith Johnson (4 January 2012). "U.S. Targets Iran's Central Bank". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ^ MacInnis, Laura (1 January 2012). "U.S. imposes sanctions on banks dealing with Iran". Reuters India. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ^ Richter, Paul & Ramin Mostaghim (9 January 2012). "Sanctions begin taking a bigger toll on Iran". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

- ^ a b "Sanctions on Iran Whipsaw Currency". Wall Street Journal. 4 January 2012. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick (20 December 2011). "As Further Sanctions Loom, Plunge in Currency's Value Unsettles Iran". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

- ^ LaFranchi, Howard (2 January 2012). "Iran currency plummets: A sign US sanctions are taking hold?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

- ^ Sanger, David E. & Annie Lowrey (27 December 2011). "Iran Threatens to Block Oil Shipments, as U.S. Prepares Sanctions". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

External links

[edit]- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 as amended (PDF/details) in the GPO Statute Compilations collection

- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 as enacted (details) in the US Statutes at Large

- H.R. 1540 on Congress.gov

- S. 1253 on Congress.gov

- Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 as amended (PDF/details)

- Cutting through the Controversy about Indefinite Detention and the NDAA (ProPublica)

- 2011 controversies in the United States

- 2012 controversies in the United States

- Acts of the 112th United States Congress

- Civil liberties in the United States

- Human rights in the United States

- Obama administration controversies

- Presidency of Barack Obama

- U.S. National Defense Authorization Acts

- Counterterrorism in the United States