Miami–Opa Locka Executive Airport

Miami-Opa Locka Executive Airport | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Miami-Dade County | ||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Miami-Dade Aviation Department (MDAD) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Miami, Florida | ||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Dade County, Florida | ||||||||||||||||||

| Operating base for | |||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 8 ft / 2 m | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 25°54′27″N 080°16′42″W / 25.90750°N 80.27833°W | ||||||||||||||||||

| Website | miami-airport.com/... | ||||||||||||||||||

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||

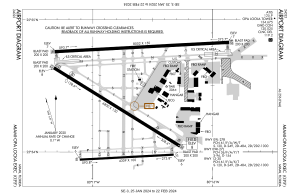

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2017) | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Miami-Opa Locka Executive Airport[2][3][4] (IATA: OPF[5], ICAO: KOPF, FAA LID: OPF) (formerly Opa-locka Airport and Opa-locka Executive Airport until 2014) is a joint civil-military airport located in Miami-Dade County, Florida[2] 11 mi (18 km) north of downtown Miami.[2] Part of the airport is in the city limits of Opa-locka.[6] The National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems for 2011–2015 called it a general aviation reliever airport.[7]

The FAA-contract control tower is staffed from 7:00 AM to 11:00 PM. The airport has four fixed-base operators. It is owned by Miami-Dade County and operated by the Miami-Dade Aviation Department.[8]

The sole remaining military activity at the airport is Coast Guard Air Station Miami, operating from federal property not deeded to the county. It hosts EADS HC-144 Ocean Sentry[9] turboprops; and MH-65 Dolphin helicopters for coastal patrol, deployment aboard medium endurance and high endurance coast guard cutters, and air-sea rescue. Much of CGAS Miami's facilities were built during World War II as part of Naval Air Station Miami.

DayJet provided on-demand jet air charter services to 44 airports in 5 states; it filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy liquidation in 2008.

The airport is served by several cargo and charter airlines that use the U.S. customs facility. Maintenance and modification of airliners up to Boeing 747 size is carried out by several aviation firms.

History

[edit]Aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss retired from aircraft development and manufacturing in the 1920s and became a real estate developer in Florida. In 1926, he founded the city of Opa-locka, naming it Opa-tisha-woka-locka (quickly shortened to Opa-locka), a Native American name that translates into the high land north of the little river with a camping place.

In late 1925, he moved the Florida Aviation Camp from Hialeah to a parcel west of Opa-locka. This small airfield was surrounded by the Opa-locka Golf Course. In 1929, he transferred the land to the City of Miami, which erected a World War I surplus hangar from Key West. The field became known as the Municipal Blimp Hangar. The following year, the Goodyear Blimp started operating out of this hangar.

In 1928, Curtiss made a separate donation of land two miles south of Opa-locka for Miami's first Municipal Airport. The Curtiss Aviation School later moved from Biscayne Bay to this airport. A larger area to the east of Miami Municipal Airport was developed during the 1930s as All-American Airport. After Curtiss died in 1930, his estate transferred a parcel of land north of the golf course and the Florida Aviation Camp to the city of Miami. The city then leased it to the United States Navy.

Curtiss had been lobbying for the establishment of the Naval Reserve Base in Miami since 1928, and this property became a Naval Reserve Aviation Training Base (NRATB), which later became an active installation renamed Naval Air Station Miami. The installation was extremely active during World War II and saw significant military construction on the main base as well as several additional auxiliary airfields in the general area. Much of this construction is still in existence today. Training in fighter, dive-bombing and torpedo bombing skills took place at various times during the base's operation. The Brewster F2A Buffalo fighter, Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber, Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber, and the Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter were some of the aircraft based at the facility. In addition to serving as headquarters for the 7th Naval District, the station supported a naval air gunnery school, a Marine Corps Air Station, a Coast Guard Station, and a small craft training center. The peak complement, reached in 1945, consisted of 7,200 officers and men and 3,100 civilian employees.[10]

Postwar, the installation returned to its former role as a Naval Air Reserve and Marine Air Reserve installation, but retained the name NAS Miami and the colloquial name of Master Field. Following the departure of the United States Navy, but the retention of U.S. Marine Corps Reserve flying and aviation support units, Master Field became Marine Corps Air Station Miami (MCAS Miami) on February 15, 1952.[11] MCAS Miami was the home of the 3d Marine Aircraft Wing from May 1952 until September 1955.[12] With the transfer of Marine Air Reserve squadrons and support units to Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Florida in 1958 and 1959, MCAS Miami was marked for closure and the air station closed as a Department of the Navy installation in 1959. Much of the former military property was transferred to Dade County and the Dade County Junior College opened on the site in 1961.

In 1962, the remainder of the former Naval Air Station Miami/Marine Corps Air Station Miami property, except for a portion reserved for the United States Coast Guard for establishment of a new coast guard air station, was transferred to Dade County and became Opa-locka Airport. However, events of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 led to much of the former air station again being requisitioned by the Department of Defense for use as an additional staging base for U.S. strike forces, augmenting the active duty air force bases and naval air stations in Florida in the event the crisis led to war. United States Air Force civil engineers from the Tactical Air Command (TAC) arrived at the airfield late in the evening of October 22 and proceeded to work around the clock. In one instance, TAC civil engineering personnel rehabilitated the aging petroleum, oil and lubricants (POL) fuel farm and distribution infrastructure originally constructed by the Navy in the 1940s, bringing the facility to fully operational status in just 3½ days. Other airfield and air base support improvements were also implemented to support tactical aircraft operations.[13] However, the crisis passed through diplomatic means and the airfield was never required to serve as a strike installation against Soviet and Cuban forces.

In 1965, Coast Guard Air Station Miami transferred its aircraft and operations from its Dinner Key seaplane installation to the Opa-locka Airport, re-establishing CGAS Miami on site. CGAS Miami continues to operate on site with EADS HC-144 Ocean Sentry fixed-wing aircraft and MH-65 Dolphin helicopters.

For the year 1963, Opa-locka was the 42nd busiest civil airport in the country by total operations count. In 1964, it was ranked eighteenth, in 1965, it was third, and in 1966 and 1967, it was second behind O'Hare. In 1971, it was down to seventeenth. In 1979, 551,873 operations were recorded, making it the seventh busiest airport in the nation.

According to Sebastián Marroquín (born Juan Pablo Escobar), his father Pablo Escobar and cousin Gustavo Gaviria "did a practice run to test-ship a hundred kilos of cocaine in a twin-engine Piper Seneca plane. It arrived at Opa Locka Airport, a private airport in the heart of Miami used exclusively by wealthy Americans, without a hitch." Subsequently, he wrote, "because they'd already successfully landed a shipment there, for more than a year Miami's Opa Locka Airport was my father's drug-trafficking destination."[14]

Some of the hijackers in the September 11 attacks trained at the airport.[15] [dead link]

On October 7, 2014, the Miami-Dade County Commission voted to change the name of the airport to "Miami-Opa Locka Executive Airport" as part of a rebranding scheme of all Miami-area airports to include the name "Miami".[16][17]

Facilities

[edit]The airport covers 1,880 acres (761 ha) at an elevation of 8 feet (2.4 m). It has three asphalt runways: 9L/27R is 8,002 by 150 feet (2,439 by 46 m); 9R/27L is 4,309 by 100 feet (1,313 by 30 m); 12/30 is 6,800 by 150 feet (2,073 by 46 m).[2]

Fire protection is provided by Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Department Station 25.[18][19]

In the year ending May 24, 2017 the airport had 147,638 operations, average 404 per day: 87% general aviation, 6% military, 6% air taxi, and <1% airline. 171 aircraft were then based at the airport: 46% single-engine, 26% multi-engine, 21% jet, 4% helicopter, and 3% military.[2]

Airline and destinations

[edit]| Airlines | Destinations | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| JSX | Dallas–Love, White Plains | [20] |

In 2023, public charter airline JSX announced it would move all of its Miami operations into the Opa-Locka Executive Airport. The company, which focuses on providing passengers with easy access to flights, decides that the smaller airport would improve ease of access and reduce the costs and complexities of operating at a bigger airport such as Miami International.[21]

Incidents

[edit]- In 1970, Douglas C-49K N12978 of Air Carrier was damaged beyond economic repair when it caught fire.[22]

- On January 21, 1982, Douglas DC-3A N211TA of Tursair, after departing from Opa-locka Airport, was destroyed in an accident at the Opa-locka West Airport (X46). The aircraft was on a training flight and the trainee pilot mishandled the engine controls, causing a temporary loss of power. The aircraft ran off the runway and collided with a tree. Inadequate supervision and the failure of the student pilot to relinquish control of the aircraft to the instructor were cited as contributing to the accident.[23]

- On May 2, 2011, a Beech E18S (N18R) crashed shortly after takeoff from OPF. The pilot was the only person on board and died in the crash. The NTSB report cited maintenance failures as contributing to the loss of power accident. The aircraft crashed into a home. Besides the death of the pilot, there were no other injuries.[24][25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Where We Fly JSX

- ^ a b c d e f FAA Airport Form 5010 for OPF PDF. Federal Aviation Administration. Effective November 8, 2018.

- ^ "Opa-locka Executive Airport". Miami-Dade Aviation Department. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- ^ "Opa-locka Executive Airport" (PDF). Florida Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- ^ "IATA Airport Code Search (OPF: Opa Locka)". International Air Transport Association. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- ^ "Opa-locka city, Florida". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 9, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "2011–2015 NPIAS Report, Appendix A" (PDF). National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems. Federal Aviation Administration. October 4, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF, 2.03 MB) on 2012-09-27.

- ^ "Opa-locka Airport: Facilities". Miami-Dade Aviation Department. Archived from the original on March 17, 2006. Retrieved April 8, 2006.

- ^ "Air Station Miami welcomes the Ocean Sentry". Coast Guard Compass. U.S. Coast Guard. October 13, 2010. Archived from the original on November 13, 2010.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-12-20. Retrieved 2014-10-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Thale, Jack (1952-02-05). "First Marine Officers Here to Open Base". The Miami Herald. Miami, Florida.

- ^ "3d MAW Lineage & Honors" (PDF). usmcu.edu. United States Marine Corps History Division. 2018-11-26. Retrieved 2023-12-17.

- ^ Maj Morris B. Rubenstein, "We Opened Opalocka," Air Force Civil Engineering Magazine, AFCE, Vol 4, No 4, Nov 1963, pp. 8-9

- ^ Escobar, Juan Pablo. My Father Pablo Escobar. Chapter 5.

- ^ Context of 'December 29-31, 2000: Atta and Alshehhi Train on Flight Simulator; Uncertainty over Whether They Gain Skills Needed for 9/11 Attacks' Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Robinson, Meesha. "Historical Opa-locka Airport Renamed". caribbeantoday.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-01. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ^ "FYI Miami: December 18, 2014 - Miami Today". miamitodaynews.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ^ "Airport Fire Rescue Division". Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Department. Miami-Dade County. Archived from the original on March 8, 2005. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- ^ "Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Stations". Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Department. Miami-Dade County. Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- ^ "JSX Shifts Miami Service to Opa-Locka Executive From late-Sep 2023". Aeroroutes. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ https://airlinegeeks.com/2023/09/10/jsx-moves-out-of-larger-airports/#

- ^ "N12978 Hull-loss description". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ^ "N211TA Accident Report, ID: MIA82FA037" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved August 17, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "One Dead After Plane Crashes in Neighborhood Near Opa-locka Airport". Miami New Times. May 2, 2011. Archived from the original on December 5, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ "ERA11FA274". NTSB. June 28, 2012. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

External links

[edit]- Opa-locka Executive Airport, official site

- "Opa-locka Executive Airport". brochure from CFASPP

- Aerial image as of February 1999 from USGS The National Map

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective November 28, 2024

- FAA Terminal Procedures for OPF, effective November 28, 2024

- Resources for this airport:

- FAA airport information for OPF

- AirNav airport information for KOPF

- ASN accident history for OPF

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart, Terminal Procedures