Reggio revolt

| Reggio revolt | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Years of Lead | |||

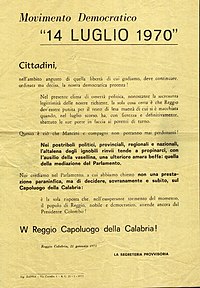

An image of the riots in Reggio Calabria in 1970–71. | |||

| Date | 5 July 1970 – 23 February 1971 | ||

| Location | Reggio Calabria, Calabria, Italy | ||

| Caused by | Decentralization and the choice of Catanzaro as the region capital | ||

| Goals | Recognition of Reggio Calabria as capoluogo (regional capital) | ||

| Methods | Strikes, street rioting and road and railway blockades | ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | According to official figures of the Italian Ministry of the Interior there were 3 dead; other sources mention 5 dead | ||

| Injuries | According to official figures of the Italian Ministry of the Interior there were 190 policemen and 37 civilians wounded; other sources mention hundreds of wounded | ||

| Arrested | Arrest and imprisonment of the revolt's leaders, like Francesco Franco | ||

The Reggio revolt occurred in Reggio Calabria, Italy, from July 1970 to February 1971. The cause of the protests was a government decision to make Catanzaro, not Reggio, regional capital of Calabria.[1][2] The nomination of a regional capital was the result of a decentralization programme of the Italian government, under which 15 governmental regions were concretized and given their own administrative councils and a measure of local autonomy.[3]

Background

[edit]

Protest in Reggio Calabria exploded in July 1970 when the much smaller town of Catanzaro (with a population of 82,000 against 160,000 in Reggio) was chosen as the regional capital of Calabria. The people of Reggio blamed their rivals' success on "the Red Barons" in Rome, a group of influential centre-left Calabrian politicians from Cosenza and Catanzaro, including Deputy Prime Minister Giacomo Mancini.[3]

On July 14, a general strike was called and five days of street fighting left one dead and several policemen injured.[3][4] A force of 5,000 armed police and Carabinieri agents was moved into the area. The national government ordered state-owned RAI TV not to report on the insurrection. Nevertheless, the revolt steadily picked up steam and sympathy.[3]

Drawn out road and railway blockades damaged the entire country. Strikes, barricades and wrecked railway tracks forced trains from the north of Italy to halt two hours short of Reggio. Italy's main north-south highway, the Autostrada del Sole (Highway of the Sun), was closed off. When the port of Reggio was blocked, hundreds of lorries and railroad freight cars were forced to remain on the other side of the Straits of Messina.[3]

Neo-fascists taking over

[edit]The revolt was taken over by young neo-fascists of the Italian Social Movement (Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI) allegedly backed by the 'Ndrangheta, a Mafia-type criminal organisation based in Calabria,[1][5][6] the De Stefano 'ndrina in particular.[7] Francesco Franco, a trade union leader from the National Italian Workers' Union (CISNAL) close to the neo-fascist movement became the informal leader of the rebel Action Committee and of the revolt. "Boia chi molla" [it] (Death to him who gives up) was the right-wing rallying cry during the revolt.[8] Most of the Italian press labeled the demonstrators fascists and hooligans against the center‐left Government in Rome;[9] however, according to Time, the revolt cut across class barriers, quoting Reggio's mayor at the time, Pietro Battaglia, who declared that it was a "citizens' revolt".[3]

The 'Ndrangheta was ready to support the subversive forces. Party and union headquarters were bombed, as well as the cars of politicians accused of treason and shops because they did not join the strikes.[4]

In the period from July–September 1970, there were 19 days of general strikes, 32 road blocks, 12 bomb attacks, 14 occupations of the railway station and two of the post office, as well as the airport and the local TV station. The local prefecture was assaulted six times and the police headquarters four times; 426 people were charged with public order offences.[10] By their own admission, many of the urban-guerilla style actions during the revolt were coordinated and led by members of National Vanguard.[11]

On 17 September 1970, Franco was arrested along with other leaders of the revolt on charges of incitement in a police sweep that targeted some 100 people. The news about the arrest provoked violent reactions, in particular in the dilapidated Sbarre suburb.[12] Two armories were stormed and about five hundred people attacked the police station.[13] At least 6,000 police men were deployed from many parts of Italy to try to stop the violence.[14] Franco was released on 23 December 1970.

After three police officers were shot and wounded in October 1970, Prime Minister Emilio Colombo decided to tackle the conflict.[3] Colombo warned that the Government would resort to force to restore order if necessary. Some 4,500 soldiers were sent to Reggio Calabria; it was the Italian Army's first assignment to crush civil disorder in 25 years.[5] The decision on the location of Calabria's government was declared "provisional" and an assurance was given that the issue would be discussed in the Italian parliament for a final decision.[3] Tensions subsided for a while, but new protests and violence broke out in January 1971 when the Parliament decided that the regional assembly had to designate the capital of Calabria.[9]

Gioia Tauro train attack

[edit]On July 22, 1970, a train derailed near the Gioia Tauro train station in Calabria, killing six people.[15] At the time, Italian authorities suspected that a bomb had caused the crash and sent troops to guard Calabrian railways.[16] In 1993, Giacomo Lauro, a former member of the 'Ndrangheta, said that he had supplied the explosives used in the bombing to people linked to the leaders of the revolt.[4] In the 1990s, Judge Guido Salvini attributed the attack to National Vanguard.[17] In February 2001, a court in Palmi, Calabria found that Vito Silverini, Vincenzo Caracciolo, and Giuseppe Scarcella (all deceased at the time) had planted the bomb.[15]

End of the conflict

[edit]

On 31 January 1971, four leaders of the rebel Action Committee were arrested on charges for instigating violence.[9] Francesco Franco was able to escape arrest initially, but was arrested on 5 June 1971, after a scuffle at a neo-fascist party rally in Rome.[18] In February 1971, journalist Oriana Fallaci had been able to interview the fugitive Franco for L'Europeo. He explained that many potentially leftist youths "today are fascists simply because they believe that the battle of Reggio is interpreted fairly only by the fascists."[4]

On 23 February 1971 armored cars entered the Sbarre neighbourhood, where a short-lived Central Sbarre Republic (Repubblica di Sbarre Centrali) had been proclaimed, and finally suppressed the revolt. According to official figures of the Italian Ministry of the Interior, there were 3 dead, and 190 policemen and 37 civilians wounded. Other sources mention 5 dead and hundreds of wounded.[8]

The so-called Colombo Package (named after then Prime minister Emilio Colombo) offering to build the Fifth Steelwork Centre in Reggio including a railroad stump and the port in Gioia Tauro, an investment of 3 billion lire which would create 10,000 jobs, softened the people of Reggio and helped to quell the revolt.[8][10] The issue of Calabria's capital was resolved by a Solomonic decision: Catanzaro and Reggio Calabria became Calabria's joint regional capitals, Catanzaro as the seat of the regional administration and Reggio Calabria as the seat of the regional parliament.[10][19]

The revolt defies any attempt to schematic classification. Issues of employment (the capital meant safe jobs in an economically depressed city) and local pride intermingled; it was mainly a matter of identity.[4] The revolt ended up by being taken over by neo-fascists[20] (relevant was also the role of the militant neo-fascist movement National Vanguard[11]) and led to unexpected electoral fortunes for the Italian Social Movement at the Italian general election in May 1972, when Franco was elected senator. The neo-fascists benefitted, because the Christian Democrats were divided, while the city was one of its fiefdoms, and the Italian Communist Party (PCI) supported the suppression of the riots.[4]

Aftermath

[edit]In October 1972, the main left wing labour unions led by the Italian General Confederation of Labour organized a conference in Reggio to regain their influence. Twenty trains were chartered to bring workers from northern and central Italy. On one of the trains full of workers and trade unionists a bomb exploded leaving five injured. Two other bombs burst on the rails in the vicinity of Lamezia Terme, while other unexploded bombs were found along the same railway line.[8] Despite the attacks, many did reach Reggio to attend the conference and street march. Franco was investigated for distributing leaflets hostile to the anti-fascist demonstration.[21] Subsequent judicial investigations of charges of provocation and terrorism ended with his acquittal.

The steelworks was never built,[2] but a conflict between different 'Ndrangheta groups over the spoils of public construction contracts to build a railroad stump, the steelwork center, and the port in Gioia Tauro, led to the First 'Ndrangheta war.[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods, p. 198

- ^ a b Partridge, Italian politics today, p. 50

- ^ a b c d e f g h No Saints in Paradise, Time Magazine, Oct. 26, 1970

- ^ a b c d e f (in Italian) La brutta avventura di Reggio Calabria, La Repubblica, January 5, 2008

- ^ a b Troops Are Sent Into Italian City, The New York Times, October 17, 1970

- ^ Town the mafia shut down, The Independent, 4 February 1996

- ^ Paoli, Broken bonds: Mafia and politics in Sicily

- ^ a b c d (in Italian) La Rivolta di Reggio Calabria, Archivio'900

- ^ a b c Disorders and a General Strike Again Paralyze Reggio Calabria, The New York Times, February 1, 1971

- ^ a b c Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy: 1943-80, pp. 156-57

- ^ a b Ferraresi, Threats to Democracy, p. 67

- ^ Italian City Is Paralyzed By Sixth Day of Turmoil, The New York Times, September 20, 1970

- ^ Protesters in Italy Fire on Police From Cathedral, The New York Times, September 18, 1970

- ^ 6,000 Policemen Are Deployed In Tense Southern Italian City, The New York Times, September 21, 1970

- ^ a b Ward, David.Contemporary Italian Narrative and 1970s Terrorism: Stranger than Fact. Springer. 2017. Page 12

- ^ Dickie, John. Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias. PublicAffairs. 2014. page 405.

- ^ Cento Bull, Anna. Italian Neofascism: The Strategy of Tension and the Politics of Nonreconciliation. Bergahn Books. 2012. Page 39. "Avanguardia Nazionale, founded by Stefano Delle Chiaie in 1959, was not among the groups charged with the Piazza Fontana massacre in the recent retrial. However, its role in stragismo was reasserted in the sentenze-ordinanze produced by Judge Salvini with reference both to the bomb attacks carried out in Rome on 12 December 1969, which produced no victims, and to other massacres carried out in the South of Italy. The most important of these was a bomb attack carried out against the train Freccia del Sud at Gioia Tauro on 22 July 1970, which caused the death of six passengers ..."

- ^ Leader of Revolt Arrested in Italy, Associated Press, June 7, 1971

- ^ Vote for a Capital In South Italy Lost By Reggio Calabria, The New York Times, February 16, 1971

- ^ Reggio Calabria Goes Back to the Barricades, The New York Times, March 22, 1973

- ^ (in Italian) Seduta di venerdì 2 febbraio 1973 Atti Parlamentari, Camera dei Deputati, February 2, 1973

- ^ Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods, p. 115

Bibliography

[edit]- Ferraresi Franco (1996). Threats to Democracy: The Radical Right in Italy after the War, Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-04499-6

- Ginsborg, Paul (1990). A History of Contemporary Italy: 1943-80, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-193167-8

- Paoli, Letizia (2003). Mafia Brotherhoods: Organized Crime, Italian Style, New York: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-515724-9 (Review by Klaus Von Lampe) (Review by Alexandra V. Orlova)

- Paoli, Letizia (2003). Broken bonds: Mafia and politics in Sicily, in: Godson, Roy (ed.) (2004). Menace to Society: Political-criminal Collaboration Around the World, New Brunswick/London: Transaction Publishers, ISBN 0-7658-0502-2

- Partridge, Hilary (1998). Italian politics today, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-4944-X

- Polimeni, Girolamo (1996). La rivolta di Reggio Calabria del 1970: politica, istituzioni, protagonisti, Pellegrini Editore, ISBN 88-8101-022-4

External links

[edit]- I giorni della rabbia - La rivolta di Reggio Calabria, La Storia siamo noi - Rai Educational