Black maternal mortality in the United States

Black maternal mortality in the United States refers to the disproportionately high rate of maternal death among those who identify as Black or African American women.[1] Maternal death is often linked to both direct obstetric complications (such as hemorrhage or eclampsia) and indirect obstetric deaths that exacerbate pre-existing health conditions.[2] In general, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines maternal mortality as a death occurring within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management.[3] In the United States, around 700 women die from pregnancy-related complications per year, with Black women facing a mortality rate nearly three times more than the rate for white women.[4]

There have been significant differences between the maternal mortality of white women versus Black women throughout history. As of 2021, the estimated national maternal mortality rate in the United States is about 32.9 per 100,000 live births––but it is about 69.9 per 100,000 live births for Black women.[5] Furthermore, data from the CDC Pregnancy Surveillance Study shows that these higher rates of Black maternal mortality are due to higher fatality rates, not a higher number of cases. Since the usual causes of maternal mortality are conditions that occur or are exacerbated during pregnancy, most instances of maternal mortality are preventable deaths.[6]

Recently, these statistics have been receiving more recognition, as researchers place more emphasis on minimizing racial/ethnic disparities seen in maternal mortality.[7] Researchers have identified several reasons for the Black-white maternal mortality disparity in the U.S., including factors like limited access to healthcare, implicit bias within the medical field, socioeconomic status, and the impact of structural racism – all of which are social determinants of health in the United States.[8] For example, Black women are more likely to live in areas with fewer healthcare resources, and studies show they often receive a lower quality of care than their white counterparts.[9] Additionally, underlying chronic health conditions such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes—conditions more prevalent among Black women due to long-standing socioeconomic inequalities—can increase the risk of maternal complications.

Recent studies indicate that more than 80% of these maternal deaths are preventable, displaying systemic issues in the healthcare system and the need for reform.[10] Within this high mortality rate, the combination of these factors and social determinants of health emphasize the significant role of structural inequalities in shaping health outcomes. Efforts are underway to address these disparities, with healthcare systems and policymakers focusing on interventions such as implicit bias training for healthcare providers, expanded Medicaid coverage for maternal care, and community-based support initiatives that prioritize Black maternal health.[11] Additional steps identified by the CDC Maternal Mortality Review Committees to prevent maternal deaths include enhancing patient-provider communication, providing comprehensive postpartum care, and supporting midwifery and doula care, particularly in underprivileged communities.

Historical context

[edit]Historical abuses in maternal care of enslaved Black women

[edit]Historically, care for Black mothers was influenced by economic motives; laws and practices from chattel slavery placed profit over human dignity. In 1662, legislators in the Virginia Colony passed Partus Sequitur Ventrem which ruled that children born from enslaved people would be enslaved themselves.[12] This created the commodification of black offspring and made Black women more profitable, increasing the slave owners' wealth without additional cost. Systemic and institutional decisions prioritized economic means over ethical treatment of Black women. The death of slaves was recorded on ledgers that also included "planting and harvesting accounts, financial ledgers, inventories of slaves and equipment, and goods and clothing allotments to slaves."[13] These records show every aspect of enslaved people's lives was quantified and valued based on the economic benefit it provided the slave owner. This meticulous documentation exemplifies the enslaved women's reduced position as property, leading to both dehumanization and commodification of their bodies. The lack of care given to women shows that their medical care was not dictated by need, but rather the economic motive to keep them alive to birth more profit.

When Britain and the United States banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1807–1808, slave owners placed more value on women. Despite midwives and nurses that took care of enslaved women, White physicians were called upon in difficult cases, to examine infertility, and to investigate infant mortality.[14] Adopting more "formal" medical interventions allowed the slave owners to increase white oversight on the reproductive lives of enslaved women. However, without proper knowledge, these White physicians could not adequately care for their patients and would verbally abuse enslaved mothers, using racist and gendered language, for deaths that were more likely the result of poor care and nutrition.[14] This abuse of power removed responsibility for outcomes from physicians and placed it on Black women themselves, compounding the systemic injustices faced by Black mothers. In the South at this time, every 1 in 2 infants were stillborn or died within their first year of life.[14] Systemic neglect and abuse caused Black mothers and infants to suffer under the guise of medical supervision.

Exploitation of Black women in gynecological research

[edit]Increased oversight by White physicians led to the abuse of Black mothers and infants as these doctors sought to advance scientific knowledge and enhance their reputations during the antebellum period. Dr. John Marion Sims, termed as the "father of gynecology," gained his title as a pioneer in the studies of gynecology by experimenting and abusing enslaved people. Since Dr. Sims performed his experiments on enslaved people, legally he only needed to acquire permission from the enslaved women's "owners".[15] Without consent, Dr.Sims performed test surgeries on enslaved women. Much research and praise has been given to Dr.Sims for his findings. However, little has been done to highlight the voices of the Black women that he abused in the name of science. Women such as Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey,[16] along with dozens of other Black enslaved women who endured painful and abusive experiments have been made voiceless due to a lack of documentation of their experiences.[17] A testament to the power he held over these enslaved women, the only documented accounts of their existence is through Dr.Sims journals and records.

The dehumanization of Black enslaved individuals has continued post enslavement as well, and developed into the myth that Black people were pain-resistant compared to white people – a belief upheld by Dr. Sims who described the enslaved women he abused as "stoic" and "resistant to pain".[18] This historic mistreatment and denial of basic rights of Black women by physicians has caused disparities in Black maternal health care and trust in the medical system among the Black community. Historically, racist myths and abuse against Black women has resulted in, "implicit bias on behalf of healthcare professionals, racial and socioeconomic disparities regarding access to care, and an absence of treatment that is culturally competent."[18]

Distrust of health institutions

[edit]

The historical context of institutionalized racism in the United States has had the effect of black people having to deal with medical and scientific racism, making the black community less likely to trust medical institutions and professionals, due to previous exploitation and abuse. Institutionalized racism is defined as policies and practices that exist across an entire society or organization and result in and support a continued unfair advantage for some people and unfair or harmful treatment of others based on race. For many years, African Americans in medicine and healthcare have faced racial injustices. Understanding what factors contribute to the racial disparity in maternal health outcomes is critical because it can illuminate where and how to address such a complex issue and focus the scope of public health prevention programs.[19] Slavery had caused black bodies to be seen as "less than" – something that could be used for entertainment or exploitation. An article in the American Journal of Public Health describes that laws making enslavement an inheritable status increased the scrutiny of black women and forced them into bearing children for the economic gain of their enslavers. In addition, many medical and surgical techniques were developed by exploiting the bodies of enslaved black women. Another article written by the Association of American Medical Colleges describe how black pain is typically written off and ignored due to medical myths surrounding black pain, such as "Black peoples nerve endings are less sensitive than white peoples" or "Black peoples skin is thicker than white peoples", leading to a lack of treatment and diagnosis for severe illnesses.[20]

Further exacerbating this mistrust in the ongoing lack of representation and culturally competent care within the healthcare system. Black patients frequently report feeling alienated or ignored when interacting with predominantly white medical staff who may lack the cultural context necessary to understand their concerns fully. Black women are often less likely to receive adequate explanations or follow-up care for symptoms, a trend liked to implicit biases within medical settings.[21] For instance, Black women suffering from severe pregnancy-related complications such as preeclampsia are frequently dismissed or not taken seriously, resulting in higher rates of mortality.[22]

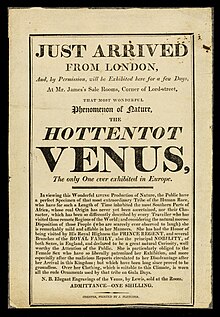

Sarah Baartman was a Hottentot woman who was paraded around in circuses around 1810–1820. She was taken from the Cape to London, presented as the "Hottentot Venus" as her buttocks were considered abnormally large by Europeans.[23] After her death, French scientist George Carvier anatomized her body in order to measure her genitalia along with other body parts. A cast of her body, skeleton, brain, and a wax mold of her genitalia were once on display in a museum.[24]

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study occurred from 1932 until 1972, where 600 economically disadvantaged African American men were unknowingly used by researchers to track the progression of syphilis, resulting in subjects going blind, insane, or experiencing other severe health problems.

An additional example of Black bodies being exploited is Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman who had samples taken of her cancerous cells without her knowledge. This tissue was given to researcher George Gey. It was found that Lacks' cells have a remarkable capability to survive and reproduce. For years after her death, scientists continued to use her cells, released her name, and released medical records to the media without her family's consent.[25] The battle of Henrietta's bodily rights is not over yet though. On October 4, 2021, the Lacks' estate announced that they will be suing the biotechnology company named Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., who says they have the intellectual rights of the HeLa cells. Lawyers for Henrietta's surviving family say the biotechnology company has continued to profit off the cells well after the origins of the HeLa cell line became well known. "The exploitation of Henrietta Lacks represents the unfortunately common struggle experienced by Black people throughout history," the suit says.[26].This enduring legacy of mistrust has carried into modern times, leaving Black women with ongoing skepticism toward their medical providers.[27]

Policy and healthcare system failures impacting Black maternal health

Despite awareness of racial disparities in maternal health outcomes, recent policy and healthcare systems have hindered efforts to reduce Black maternal mortality. Many healthcare policies fail to address the unique challenges Black women face. For example, Medicaid, which funds 42% of births in the United States, often limits postpartum coverage to just 60 days in many states.[28] This cutoff affects all mothers relying on Medicaid, but it disproportionately impacts Black women, who are more likely to depend on Medicaid due to socioeconomic disparities often resulting from systemic biases and historical oppressions such as redlining [29]. Research shows that a significant number of pregnancy-related deaths occur up to a year after childbirth, with Black mothers facing higher rates of postpartum complications.[30] Efforts to extend Medicaid coverage have been met with resistance or have only been adopted in some states, leading to inconsistent support that disproportionately affects Black mothers in low-income communities.[31]

Medicaid's postpartum coverage limitations are harmful given the elevated health risks Black women face in the months following childbirth. Conditions such as postpartum depression, hypertension, and infections often require medical attention beyond the 60-day coverage period.[32] Without consistent postpartum care, Black mothers are at risk for life-threatening complications. Efforts to extend Medicaid coverage have been met with varying levels of resistance, with some state opting out entirely, which leaves Black mothers without the necessary resources to manage postpartum health challenges.[33]

Moreover, implicit biases training programs for healthcare providers have mixed results. Though training is designed to reduce racial bias in patient interactions, studies indicate that one-time training sessions may not effectively change deep-rooted biases. A study from the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities found that implicit bias training alone does not significantly reduce instances of discriminatory practices unless followed by continued education and institutional accountability measures.[34]

Legislation such as the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act in 2021 aimed to address these systemic issues by proposing measures to improve data collection on maternal mortality, fund community-based maternal health programs, and increase access to mental health resources for Black mothers.[35] However, much of the act remains stalled in Congress, highlighting the political barriers to implementing changes that could improve Black maternal health outcomes. Federal mandates to improve maternal healthcare are essential for closing these gaps, yet state-level inconsistencies continue to create disparities in care accessibility. While some states have adopted components of the Momnibus Act, lack of national enforcement results in uneven access to maternal health services, affecting mothers in underrepresented areas.[36]

Causes

[edit]Access to maternal care

[edit]The setting where a woman gives birth is another significant factor in determining the outcome of the birth. Specifically, non-teaching, black-serving hospitals have been found to extremely increase the rate of morbidity for black women during pregnancy. In the states of Pennsylvania, Missouri, and California, the journal article "Black-white disparities in maternal in-hospital mortality according to teaching and black-serving hospital status" discovered that between the years of 1995 to 2000, out of every 100,000 patients in a hospital, 11.5 black women died during pregnancy, and 4.8 white women died during pregnancy. In addition, data suggests that non-teaching hospitals tend to have fewer resources, outdated equipment, and reduced access to specialized care teams, which further exacerbates the risk for Black mothers in these facilities. Black-serving hospitals are often underfunded, with fewer trained staff in obstetrics and maternal care, leading to higher rates of complications and mortality.[37] The figures show that the data for maternal morbidity from a black woman to a white woman almost doubled, and they are mainly attributed to whether the hospital is teaching or non-teaching and whether it is a black serving hospital (Burris 2021). "Mortality rates among U.S. women of reproductive age" also found that the greatest risk for mortality during pregnancy resulted in deaths from women's health outcomes over the course of their lifetime which can also be largely attributed to the healthcare settings that are accessible for all pregnant women (Gemmill, 2022). According to "Urban-rural differences in pregnancy-related deaths," within urban-rural communities, black women had higher mortality ratios within the same age groups compared to non-Hispanic Americans proving the necessity for accessible healthcare for all pregnant women regardless of their environment or setting (Merkt, 2021). The disparity in healthcare access is particularly severe in rural Black communities, where travel time to the nearest maternal healthcare facility can exceed an hour. The lack of nearby facilities forces many Black women to forgo timely prenatal care, increasing risks of complications.[38]

Both prenatal care and postnatal are used to support pregnant women at different stages and monitor potential risk factors in order to make pregnancy and delivery as safe and healthy as possible. The literature shows that increasing access to prenatal care through public health departments caused a subsequent decrease in black maternal mortality rates.[39][40] Despite this, Black women continue to face barriers in accessing consistent prenatal care, with systemic biases often resulting in Black women receiving less comprehensive screening for conditions compared to white counterparts. In some areas, Black women report experiencing dismissive treatment during prenatal visits, which discourages further attendance and follow-ups.[41] Furthermore, having fewer than 5 prenatal care visits, not attending prenatal care appointments, and accessing prenatal care later in a pregnancy are associated with maternal mortality. Black women are less likely to initiate prenatal care, with 10% of black women receiving late (third trimester) or no prenatal care, compared with 4% of white women.[42] Late initiation of prenatal care is linked with higher incidence of preventable conditions like anemia and severe hypertension, which increases risk of mortality. The Center for Reproductive Rights emphasizes that addressing these barriers could save thousands of lives annually if equitable access to prenatal care were prioritized.[43]

"Maternal care deserts" are an important factor when it comes to access to prenatal and postnatal care. A maternal care desert is defined as a county with no hospital offering obstetric care and no OB/GYN or certified nurse midwife providers.[44] Around 15 million women live in these maternity care deserts, with many of these women being minorities. In these regions, the absence of maternal care facilities forces many women to rely on emergency rooms for childbirth, where the staff may lack specialized training in maternal health. Black women are disproportionately affected as they are more likely to live in areas with limited healthcare facilities. This lack of access has been linked to increased rates of emergency C-sections, untreated complications, and inadequate postpartum follow-up.[45] A study done on the relation of maternal care deserts and pregnancy associated mortality found that "the risk of death during pregnancy and up to 1 year postpartum owing to any cause (pregnancy-associated mortality) and in particular death owing to obstetric causes (pregnancy-related mortality) was significantly elevated among women residing in maternity care deserts compared with women in areas with greater access."[44] Other obstacles such as lack of providers accepting public insurance such as Medicaid and transportation requirements to get to prenatal appointments affect black women more than white women in the United States.[39]

Intersection of race, socioeconomic status, and disability

[edit]Income has been well studied as a social determinant of health, and it has been found that worse health outcomes at all-time points surrounding pregnancy are associated with lower socioeconomic status and income levels. For Black mothers, the impact of low socioeconomic status is compounded by racial discrimination, resulting in limited access to quality healthcare and higher incidences of stress-related health issues such as preterm labor. A 2022 report from the American Public Health Association highlights that Black women in low0-income brackets are more likely to be uninsured, leading to gaps in critical prenatal and postnatal care services.[46] Lack of insurance/using Medicaid and experiencing homelessness are associated with severe morbidity rates, and are all more likely to apply to black women and increase their risk of maternal death.[39]

Systemic racism contributes to the greater likelihood of black women to belong to lower socioeconomic classes. However, it is important to note that Black women across all socioeconomic statuses and education levels experience the same extent of racism both during the birthing process and after, as noted in Black women's experiences in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit following birth.[47] For example, even Black women with private insurance report facing racial biases that result in less attentive care during labor. The National Institute of Health found that Black women were less likely to receive timely pain relief and more likely to experience dismissive attitudes from healthcare providers, which negative impacts health outcomes.[48] The intersection of race and healthcare access highlights that biasees persist regardless of socioeconomic improvement for Black mothers. A study from the Nature Public Health Collection journal pointed out that the COVID-19 pandemic increases the vulnerability of black women who are more likely to work at jobs that carry greater exposure risks to COVID-19, and more likely to lose income due to unemployment. This is in addition to the pandemic making accessing perinatal care more challenging, and making income disparities even more stark. The researchers who authored this study recommend that the interlocking factors affecting black mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic be specifically addressed in order to see tangible improvements in maternal health outcomes.[49]

More and more women with disabilities are becoming mothers, but few federally-funded programs offer support or services to women with disabilities.[50] Black mothers with disabilities have increased barriers to accessing maternal services, which increases health and mortality risks for the mother. Data from the American Disabilities Act Network reveals that many healthcare facilities are not adequately equipped for disabled mothers, lacking accessible equipment and trained staff. This lack of accessibility has been directly linked to a rise in preventable complications, such as increased instances of physical strain and untreated symptoms during pregnancy.[51] Women with disabilities also have higher pregnancy complications, preterm deliveries, and low birth infants.[52]

One of the most determinant factors on the outcome of a woman's pregnancy has been statistically proven to be the healthcare that the mother has access to. According to Race, medicaid coverage, and equity in maternal morbidity, there is a large disproportion of mothers receiving adverse reactions during or after pregnancy with Medicaid compared to those with private insurance. This research found that black women with medicaid are 50% more likely to have severe maternal mortality. Furthermore, Medicaid-covered Black women experience lower rates of access to preventative care services, leading to greater likelihood of encountering emergency interventions during childbirth. In this study, most of the white women had private insurance which resulted in them being half as likely to have a severe maternal morbidity experience compared to black women with Medicaid (Brown, 2021). According to "Incidence of severe maternal morbidity by race and payer status at an academic medical system," by doing a similar study, it was established that black women with Medicaid have the highest rates of mortality, and white women with private insurance have the lowest rates of mortality proving the insurance that the pregnant mother has is one of the main determinants in their healthcare outcome (Mallampati, 2022). [53]

Pre-existing conditions

[edit]A study conducted by Amy Metcalfe, James Wick, and Paul Ronksley analyzing trends in maternal mortality from 1993 to 2012 showed that the percentage of black women with pre-existing conditions increased from about 10% to about 17%, the highest out of all other racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Black women are more likely to have adverse pregnancy outcomes which make them more susceptible to cardiovascular diseases putting them at a greater risk for maternal mortality.[54] Black women are also more likely to already have pre-existing cardiovascular disease. They also have greater odds of developing preeclampsia, along with an increased prevalence of chronic disease and obesity.[55] Black women are more likely to have unplanned pregnancies as well–and are thus more likely to lack prior monitoring and treatment of pre-existing conditions before, during, and after a pregnancy.[56] A study conducted in 2009 also showed that black infant mortality rates were five times higher than white infant mortality rates. The health of newborn children has a direct correlation to the physical health of the mother through reproduction, pregnancy and birth, which provides further evidence of poor maternal health resources and care received by black mothers.[57]

Racial bias

[edit]In 2020 the American Public Health Association declared structural racism a public health crisis, which was attributed to historical forces as well as current events.[58] There have been thousands of studies analyzing the racial bias against Black people in the healthcare system.[59] Overall, Blacks are less likely to receive the same quality care as their White counterparts. Clinician bias is one of the largest contributors to this disparity. This bias can be either implicit or explicit, but both are harmful to the well-being of Black patients. Explicit biases have generally been measured with self-reports while implicit biases are measured through "validated tests of unconscious association".[59] A lot of empirical evidence strongly suggests that White physicians hold negative implicit racial biases and negative explicit racial stereotypes, which causes them to be influenced by these biases when it comes to making medical decisions for their patients. In turn, this contributes to the racial inequities prominent in the healthcare system.

In general, Black Americans are under-treated for pain when compared with White Americans.[60] Black patients are less likely to receive pain medication, and when they do, they are more likely to receive a lower quantity than their White counterparts. This phenomenon contributes to Black maternal mortality, aiding in the dismissal of Black women's pain by medical professionals.[27] A Harvard School of Public Health publication discussed this phenomenon by collecting numerous examples of medical professionals being dismissive or providing delayed care to Black mothers expressing pain or problematic symptoms.[61] The publication tells the story of Shalon Irving, a Black woman who experienced symptoms such as high blood pressure, blurry vision, and hematoma after childbirth. However, her doctors advised her to not take further action, and Irving died soon after. According to the author, this was just one instance of medical caregivers being less likely to take Black women's concerns seriously, contributing to maternal death.[61]

Maternal mortality is connected to racism, with Black women dying from medical issues that are preventable yet not being listened to when they complain about pain. Black women are perceived to be resilient and strong as a result of persistence during societal changes, personal crisis, and in the face of racial adversity. Black women have increased levels of stress as a result of this "Superwoman schema".[62] More specifically along the lines of black maternal health, black women are also seen to receive birth control-related distrust in higher frequencies compared to white women.[63] Although poor Black women are more susceptible to maternal mortality, the risk still exists for other Black women with better resources. For example, tennis player Serena Williams almost suffered a fatality postpartum when she developed a pulmonary embolism. This was a result of the doctors not listening to her when she expressed her health concerns, and not considering those concerns serious enough to be acted upon urgently.[64] According to a study done by the Robert Johnson Fund, over 22% of Black women report discrimination from medical professionals when they are seeking help.[65]

In 2019, Black maternal health advocate and Parents writer Christine Michel Carter interviewed Vice President Kamala Harris. As a senator, in 2019 Harris reintroduced the Maternal Care Access and Reducing Emergencies (CARE) Act which aimed to address the maternal mortality disparity faced by women of color by training providers on recognizing implicit racial bias and its impact on care. Harris stated:

We need to speak the uncomfortable truth that women—and especially Black women—are too often not listened to or taken seriously by the health care system, and therefore they are denied the dignity that they deserve. And we need to speak this truth because today, the United States is 1 of only 13 countries in the world where the rate of maternal mortality is worse than it was 25 years ago. That risk is even higher for Black women, who are three to four times more likely than white women to die from pregnancy-related causes. These numbers are simply outrageous.

Abortion access

[edit]

Unsafe abortion is a major contributing factor to maternal mortality and morbidity and Black women, who are more likely to have unplanned pregnancies and be of lower socioeconomic status, are more likely to undergo unsafe abortions. Black women have consistently had higher abortion rates than White women, which means that restrictions to safe abortions will disproportionately affect them. And over the last couple of years, access to safe abortions in the United States has become increasingly restrictive.[66] These restrictions include bans on particular methods of abortion care, Targeted Restriction of Abortion Provider (TRAP) laws, and specifically trigger laws which have banned abortion in some states immediately after Roe v. Wade was overturned in 2022.[67] The lack of access to safe abortions has been exacerbated within the past decades as states pass strict regulations around abortion especially in southern states with higher proportions of African Americans. The World Health Organization recognizes that in order to help decrease maternal mortality, access to safe abortions must be increased. And while few studies have inquired as to whether there is a direct link between unsafe abortion and maternal mortality, the studies that have been done support this link.

Preventative measures

[edit]Medical

[edit]In order to prevent maternal deaths from occurring, methods have been identified which decrease maternal mortality overall along with the accompanying health disparities. Researchers believe that by improving the quality of care within hospitals, maternal mortality would be properly addressed and accounted for. It has been suggested that higher quality hospitals, that have multiple layers of care such as administrative and patient advocates, are consistent with their collection of feedback from patients which allows for further improvement in regards to addressing maternal mortality. Additionally, maternal health-related services, such as an intensive care unit, 24-hour anesthesia, and OB/GYN specialists, contribute to the decrease of maternal mortality rate. With the prioritization of standardized care and early risk factors, issues that may lead to maternal mortality in Black women, such as hypertension, hemorrhaging, and eclampsia, would be directly addressed.[68] The new study also found that these disparities were concentrated in a few causes of death. Postpartum cardiomyopathy (heart failure) and the blood pressure disorders preeclampsia and eclampsia were the leading causes of maternal death in Black women, with mortality rates five times higher than in white women. Pregnant and postpartum Black women were also more than twice as likely as white women to die from hemorrhage or embolism (blood vessel blockage). It is also important to recognize that only 87% of Black women have health insurance and most have gaps in coverage at some point in their lives. To improve the health of Black women, policies need to be implemented that focus on the expansion and maintenance of the care and coverage.[69] In addition to improving medical care for black women, improving the living conditions of black families would also help to eliminate declining physical health conditions, as the health of communities has been proven to link directly to the overall health of the individuals who live there.[57]

Some have argued against the conventional classification of race as a risk factor in health, instead calling for the recognition of racism and poverty as the underlying factors contributing to Black maternal mortality and other poor health outcomes for Black individuals.[70] To address the medical racism that exists within healthcare, which ultimately leads to maternal mortality, many states and cities have taken initiative by creating programs to address the high levels of Black maternal mortality. Most notably, in 2018, an initiative was created in New York City in which healthcare workers had to undergo implicit bias training.[70] In addition, experts in multiple sectors, such as medicine, sociology, and law, have said that deliberately addressing racism, both within and outside of the medical field, is necessary to decrease the rate of Black maternal mortality. According to "Epidemiology of racial/ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality," screenings are a large component of prevention for severe maternal morbidity which directly correlates to the increase in black mortality during pregnancy as well as access to resources (Holdt, 2017). This likely attributes to the also significant gap from black to white pregnancies to be readmitted post-pregnancy. Using the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project from 2012 to 2014, it was discovered that black women were more likely to be readmitted postpartum, to suffer severe maternal morbidity, and suffer life-threatening complications (Aziz, 2019). By increasing screening before and during pregnancy and access to better maternal healthcare for those with Medicaid, maternal mortality for black women and post-pregnancy complications could significantly decrease; in addition, new protocols regarding how often pregnant women, especially black women, should be screened for hypertensive disorders while pregnant.[71]

See also

[edit]- Death of Amber Nicole Thurman

- Death of Chaniece Wallace

- Death of Sha-Asia Washington

- Weathering hypothesis

- Maternal Health

- Race and maternal health in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ "Maternal Mortality". www.cdc.gov. October 27, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ Cresswell, Jenny (February 23, 2023). "Maternal Deaths". World Health Organization – via WHO.

- ^ "Provisional Maternal Death Rates". www.cdc.gov. October 16, 2024. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ CDC (June 16, 2024). "Working Together to Reduce Black Maternal Mortality". Women’s Health. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ "Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2021". www.cdc.gov. March 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ "Racial Disparities Persist in Maternal Morbidity, Mortality and Infant Health". AJMC. June 14, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ Oribhabor, Geraldine I; Nelson, Maxine L; Buchanan-Peart, Keri-Ann R; Cancarevic, Ivan (2020). "A Mother's Cry: A Race to Eliminate the Influence of Racial Disparities on Maternal Morbidity and Mortality Rates Among Black Women in America". Cureus. 12 (7): e9207. doi:10.7759/cureus.9207. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 7366037. PMID 32685330.

- ^ MacDorman, Marian F.; Thoma, Marie; Declcerq, Eugene; Howell, Elizabeth A. (September 2021). "Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Maternal Mortality in the United States Using Enhanced Vital Records, 2016‒2017". American Journal of Public Health. 111 (9): 1673–1681. doi:10.2105/ajph.2021.306375. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 8563010. PMID 34383557.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (June 1, 2019). "Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "What Are Maternal Morbidity and Mortality?". orwh.od.nih.gov. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ "ORWH: In the Spotlight". orwh.od.nih.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ "EIHS Lecture: "Partus Sequitur Ventrem: Slave Law and the History of Women in Slavery" | U-M LSA Eisenberg Institute for Historical Studies (EIHS)". lsa.umich.edu. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ Steckel, Richard H. (1986). "A Peculiar Population: The Nutrition, Health, and Mortality of American Slaves from Childhood to Maturity". The Journal of Economic History. 46 (3): 721–741. doi:10.1017/S0022050700046842. ISSN 0022-0507. JSTOR 2121481. PMID 11617309.

- ^ a b c Owens, Deirdre Cooper; Fett, Sharla M. (October 2019). "Black Maternal and Infant Health: Historical Legacies of Slavery". American Journal of Public Health. 109 (10): 1342–1345. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305243. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 6727302. PMID 31415204.

- ^ Urell, Aaryn (August 29, 2019). "Medical Exploitation of Black Women". Equal Justice Initiative. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ "Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey". ABOG. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

- ^ "Betsey, Lucy, and Anarcha Days of Recognition". www.acog.org. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ a b "Unpacking the Root Causes of Black Maternal Mortality - National Organization for Women". now.org. May 3, 2023. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ Nuriddin, Ayah; Mooney, Graham; White, Alexandre I R (October 2020). "Reckoning with histories of medical racism and violence in the USA". The Lancet. 396 (10256): 949–951. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32032-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7529391. PMID 33010829.

- ^ "How we fail black patients in pain".

- ^ Washington, Ariel; Randall, Jill (April 2023). ""We're Not Taken Seriously": Describing the Experiences of Perceived Discrimination in Medical Settings for Black Women". Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 10 (2): 883–891. doi:10.1007/s40615-022-01276-9. ISSN 2197-3792. PMC 8893054. PMID 35239178.

- ^ Petersen, Emily E. (2019). "Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths — United States, 2007–2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (35): 762–765. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 6730892. PMID 31487273.

- ^ Jansen, Jonathan; Walters, Cyrill, eds. (April 1, 2020). Fault Lines: A primer on race, science and society. doi:10.18820/9781928480495. hdl:10019.1/109577. ISBN 9781928480495. S2CID 229145601.

- ^ The gender and science reader. Muriel Lederman, Ingrid Bartsch. London: Routledge. 2001. ISBN 0-415-21357-6. OCLC 44426765.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Henrietta Lacks: science must right a historical wrong". Nature. 585 (7823): 7. September 1, 2020. Bibcode:2020Natur.585....7.. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02494-z. PMID 32873976. S2CID 221466551.

- ^ "Henrietta Lacks' estate sued a company saying it used her 'stolen' cells for research". NPR. Associated Press. October 4, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Owens, Deirdre Cooper; Fett, Sharla M. (August 15, 2019). "Black Maternal and Infant Health: Historical Legacies of Slavery". American Journal of Public Health. 109 (10): 1342–1345. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305243. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 6727302. PMID 31415204.

- ^ "Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Extension Tracker". KFF. August 1, 2024. Retrieved November 1, 2024.

- ^ Brown, T. (2012). The Intersection and Accumulation of Racial and Gender Inequality: Black Women’s Wealth Trajectories. The Review of Black Political Economy, 39(2), 239-258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12114-011-9100

- ^ "Black Women Over Three Times More Likely to Die in Pregnancy, Postpartum Than White Women, New Research Finds". PRB. Retrieved November 1, 2024.

- ^ Pillai, Akash; Hinton, Elizabeth; Rudowitz, Robin; Published, Samantha Artiga (July 1, 2024). "Medicaid Efforts to Address Racial Health Disparities". KFF. Retrieved November 1, 2024.

- ^ "Optimizing Postpartum Care". www.acog.org. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- ^ "Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the US". www.marchofdimes.org. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- ^ FitzGerald, Chloë; Hurst, Samia (March 1, 2017). "Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review". BMC Medical Ethics. 18 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8. ISSN 1472-6939. PMC 5333436. PMID 28249596.

- ^ "The Momnibus Act | Black Maternal Health Caucus". blackmaternalhealthcaucus-underwood.house.gov. March 7, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth A. (June 2018). "Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality". Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology. 61 (2): 387–399. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000349. ISSN 0009-9201. PMC 5915910. PMID 29346121.

- ^ Radley, David C.; Shah, Arnav; Collins, Sara R.; Powe, Neil R.; Zephyrin, Laurie C. (April 18, 2024). "Advancing Racial Equity in U.S. Health Care". www.commonwealthfund.org. doi:10.26099/vw02-fa96. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- ^ Burris, H. H., Passarella, M., Handley, S. C., Srinivas, S. K., & Lorch, S. A. (2021). Black-white disparities in maternal in-hospital mortality according to teaching and black-serving hospital status. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 225(1), 1–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.01.004 Gemmill, A., Berger, B. O., Crane, M. A., & Margerison, C. E. (2022). Mortality rates among u.s. women of reproductive age, 1999-2019. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 62(4), 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.10.009 Merkt, P. T., Kramer, M. R., Goodman, D. A., Brantley, M. D., Barrera, C. M., Eckhaus, L., & Petersen, E. E. (2021). Urban-rural differences in pregnancy-related deaths, United States, 2011-2016. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 225(2), 1–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.02.028

- ^ a b c Gadson, Alexis; Akpovi, Eloho; Mehta, Pooja K. (August 1, 2017). "Exploring the social determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in prenatal care utilization and maternal outcome". Seminars in Perinatology. Strategies to reduce Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. 41 (5): 308–317. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.008. ISSN 0146-0005. PMID 28625554.

- ^ NAM JIN YOUNG; Eun-Cheol Park (May 2018). "The Association between Adequate Prenatal Care and Severe Maternal Morbidity: A Population-based Cohort Study". Journal of the Korean Society of Maternal and Child Health. 22 (2): 112–123. doi:10.21896/jksmch.2018.22.2.112. ISSN 1226-4652. S2CID 81182382.

- ^ "What I'd Like Everyone to Know About Racism in Pregnancy Care". www.acog.org. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- ^ Gadson, Alexis; Akpovi, Eloho; Mehta, Pooja K. (August 2017). "Exploring the social determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in prenatal care utilization and maternal outcome". Seminars in Perinatology. 41 (5): 308–317. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.008. ISSN 0146-0005. PMID 28625554.

- ^ "Maternal Health". Center for Reproductive Rights. October 16, 2024. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Wallace, Maeve; Dyer, Lauren; Felker-Kantor, Erica; Benno, Jia; Vilda, Dovile; Harville, Emily; Theall, Katherine (March 2021). "Maternity Care Deserts and Pregnancy-Associated Mortality in Louisiana". Women's Health Issues. 31 (2): 122–129. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2020.09.004. ISSN 1049-3867. PMC 8005403. PMID 33069560.

- ^ Lister, Rolanda L (November 22, 2019). "Black Maternal Mortality-The Elephant in the Room". World Journal of Gynecology & Womens Health. 3 (1). doi:10.33552/WJGWH.2019.03.000555. PMC 7384760. PMID 32719828.

- ^ Daw, Jamie R.; Kolenic, Giselle E.; Dalton, Vanessa K.; Zivin, Kara; Winkelman, Tyler; Kozhimannil, Katy B.; Admon, Lindsay K. (April 2020). "Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Perinatal Insurance Coverage". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 135 (4): 917–924. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003728. ISSN 0029-7844. PMC 7098441. PMID 32168215.

- ^ Davis, Dána-Ain (2019). Reproductive Injustice: Racism, Pregnancy, and Premature Birth. New York: New York University Press.

- ^ Cousin, Lakeshia; Johnson-Mallard, Versie; Booker, Staja Q. (April 2022). ""Be Strong My Sista'": Sentiments of Strength From Black Women With Chronic Pain Living in the Deep South". Advances in Nursing Science. 45 (2): 127–142. doi:10.1097/ANS.0000000000000416. ISSN 0161-9268. PMC 9064901. PMID 35234672.

- ^ "PRIME PubMed | Syndemic Perspectives to Guide Black Maternal Health Research and Prevention During the COVID-19 Pandemic". www.unboundmedicine.com. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ Long-Bellil, Linda; Valentine, Anne; Mitra, Monika (2021), Lollar, Donald J.; Horner-Johnson, Willi; Froehlich-Grobe, Katherine (eds.), "Achieving Equity: Including Women with Disabilities in Maternal and Child Health Policies and Programs", Public Health Perspectives on Disability: Science, Social Justice, Ethics, and Beyond, New York, NY: Springer US, pp. 207–224, doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0888-3_10, ISBN 978-1-0716-0888-3, S2CID 225010310, retrieved October 9, 2021

- ^ Signore, Caroline; Davis, Maurice; Tingen, Candace M.; Cernich, Alison N. (February 1, 2021). "The Intersection of Disability and Pregnancy: Risks for Maternal Morbidity and Mortality". Journal of Women's Health. 30 (2): 147–153. doi:10.1089/jwh.2020.8864. ISSN 1540-9996. PMC 8020507. PMID 33216671.

- ^ Mheta, Doreen; Mashamba-Thompson, Tivani P. (May 16, 2017). "Barriers and facilitators of access to maternal services for women with disabilities: scoping review protocol". Systematic Reviews. 6 (1): 99. doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0494-7. ISSN 2046-4053. PMC 5432992. PMID 28511666.

- ^ Brown, C. C., Adams, C. E., & Moore, J. E. (2021). Race, medicaid coverage, and equity in maternal morbidity. Women's Health Issues : Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health, 31(3), 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2020.12.005 Mallampati, D., Federspiel, J., Wheeler, S. M., Small, M., Hughes, B. L., Menard, K., Quist-Nelson, J., & Meng, M. L. (2022). Incidence of severe maternal morbidity by race and payer status at an academic medical system. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Supplement, 226(1), 440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.731

- ^ Lister, Rolanda L; Drake, Wonder; Scott, Baldwin H; Graves, Cornelia (2019). "Black Maternal Mortality-The Elephant in the Room". World Journal of Gynecology & Women's Health. 3 (1). doi:10.33552/wjgwh.2019.03.000555. ISSN 2641-6247. PMC 7384760. PMID 32719828.

- ^ Kuriya, Anita; Piedimonte, Sabrina; Spence, Andrea R.; Czuzoj-Shulman, Nicholas; Kezouh, Abbas; Abenhaim, Haim A. (February 18, 2016). "Incidence and causes of maternal mortality in the USA". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 42 (6): 661–668. doi:10.1111/jog.12954. ISSN 1341-8076. PMID 26890471. S2CID 1087698.

- ^ Metcalfe, Amy; Wick, James; Ronksley, Paul (2018). "Racial disparities in comorbidity and severe maternal morbidity/mortality in the United States: an analysis of temporal trends". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 97 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1111/aogs.13245. ISSN 1600-0412. PMID 29030982. S2CID 207028740.

- ^ a b B’MORE FOR HEALTHY BABIES A Collaborative Funding Model to Reduce Infant Mortality in Baltimore. (n.d.). https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/AECF-BmoreforHealthyBabies-2018.pdf

- ^ Tyler, Elizabeth (2022). "Black mothers matter: The social, political and legal determinants of black maternal health across the lifespan". Journal of Health Care and Law. 25 (1): 49–89. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b van Ryn, Michelle; Burgess, Diana J.; Dovidio, John F.; Phelan, Sean M.; Saha, Somnath; Malat, Jennifer; Griffin, Joan M.; Fu, Steven S.; Perry, Sylvia (April 1, 2011). "The Impact of Racism on Clinician Cognition, Behavior, and Clinical Decision Making". Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 8 (1): 199–218. doi:10.1017/S1742058X11000191. ISSN 1742-058X. PMC 3993983. PMID 24761152.

- ^ FitzGerald, Chloë; Hurst, Samia (March 1, 2017). "Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review". BMC Medical Ethics. 18 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8. ISSN 1472-6939. PMC 5333436. PMID 28249596.

- ^ a b Boston, 677 Huntington Avenue; Ma 02115 +1495‑1000 (December 18, 2018). "America is Failing its Black Mothers". Harvard Public Health Magazine. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Woods-Giscombé, Cheryl L. (May 2010). "Superwoman Schema: African American Women's Views on Stress, Strength, and Health". Qualitative Health Research. 20 (5): 668–683. doi:10.1177/1049732310361892. ISSN 1049-7323. PMC 3072704. PMID 20154298.

- ^ Rosenthal, L., & Lobel, M. (2018). Gendered racism and the sexual and reproductive health of Black and Latina Women. Ethnicity & Health, 25(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1439896

- ^ 43 Campbell L. Rev. 243 (2021) Can You Hear Me?: How Implicit Bias Creates a Disparate Impact in Maternal Healthcare for Black Women, Glover, Kenya [ 34 pages, 243 to [vi] ]

- ^ "Black Women's Maternal Health". www.nationalpartnership.org. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Verma, Nisha; Shainker, Scott A. (August 2020). "Maternal mortality, abortion access, and optimizing care in an increasingly restrictive United States: A review of the current climate". Seminars in Perinatology. 44 (5): 151269. doi:10.1016/j.semperi.2020.151269. ISSN 1558-075X. PMID 32653091. S2CID 220502603.

- ^ Ellmann, Nora (August 27, 2020). "State Actions Undermining Abortion Rights in 2020". Center for American Progress. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth A; Zeitlin, Jennifer (August 2017). "Improving Hospital Quality to Reduce Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality". Seminars in Perinatology. 41 (5): 266–272. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.002. ISSN 0146-0005. PMC 5592149. PMID 28735811.

- ^ "Black Women's Maternal Health". www.nationalpartnership.org. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Owens, Deirdre Cooper; Fett, Sharla M. (August 15, 2019). "Black Maternal and Infant Health: Historical Legacies of Slavery". American Journal of Public Health. 109 (10): 1342–1345. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305243. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 6727302. PMID 31415204.

- ^ Aziz, A., Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., Siddiq, Z., Wright, J. D., Goffman, D., Sheen, J.-J., D'Alton, M. E., & Friedman, A. M. (2019). Maternal outcomes by race during postpartum readmissions. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 220(5), 1–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.016 Holdt Somer, S. J., Sinkey, R. G., & Bryant, A. S. (2017). Epidemiology of racial/ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Seminars in Perinatology, 41(5), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.001