Arabic numerals: Difference between revisions

DocWatson42 (talk | contribs) Cleaned up references and other matters. Tag: Reverted |

It certainly is NOT undisputed. Need ref saying this term means this subset of |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|cWidth=300 |

|cWidth=300 |

||

|cHeight=50 |

|cHeight=50 |

||

|Description=Arabic numerals set in [[Source Sans]] |

|Description=Arabic numerals set in [[Source Sans]]}} |

||

}} |

|||

{{numeral systems}} |

{{numeral systems}} |

||

| Line 20: | Line 19: | ||

It was in the [[Algeria]]n city of [[Bejaia]] that the [[Italian people|Italian]] scholar [[Fibonacci]] first encountered the numerals; his work was crucial in making them known throughout Europe. European trade, books, and [[colonialism]] helped popularize the adoption of Arabic numerals around the world. The numerals have found worldwide use significantly beyond the contemporary [[spread of the Latin alphabet]], intruding into the writing systems in regions where other numerals had been in use, such as [[Chinese numerals|Chinese]] and [[Japanese numerals|Japanese]] writing. |

It was in the [[Algeria]]n city of [[Bejaia]] that the [[Italian people|Italian]] scholar [[Fibonacci]] first encountered the numerals; his work was crucial in making them known throughout Europe. European trade, books, and [[colonialism]] helped popularize the adoption of Arabic numerals around the world. The numerals have found worldwide use significantly beyond the contemporary [[spread of the Latin alphabet]], intruding into the writing systems in regions where other numerals had been in use, such as [[Chinese numerals|Chinese]] and [[Japanese numerals|Japanese]] writing. |

||

They are also called '''Western Arabic numerals''', '''Ghubār numerals''',<ref>{{cite web |title=Arabic Numerals (Ghubar Numerals)|url=http://materiaislamica.com/index.php/Arabic_Numerals}}</ref>{{unreliable source?|date=September 2021}} '''Hindu-Arabic numerals''',{{sfn|Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered|2003|p=10}}<ref name="AHB">{{cite web|url=https://www.ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?id=A5414100|title=Arabic numeral|work=[[American Heritage Dictionary]]|date=2020|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company}}</ref><ref name="Britannica">{{cite encyclopedia|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hindu-Arabic-numerals|title=Hindu-Arabic numerals|encyclopedia=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]|date=2017|publisher=Britannica Group}}</ref> or '''[[ASCII]] digits'''.<ref>[https://www.unicode.org/terminology/digits.html Terminology for Digits]. Unicode Consortium.</ref> The ''[[Oxford English Dictionary]]'' uses lowercase ''Arabic numerals'' for them, and capitalized ''Arabic Numerals'' to refer to the [[Eastern Arabic numerals|Eastern digits]].<ref>"Arabic", ''Oxford English Dictionary'', 2nd edition</ref> |

They are also called '''Western Arabic numerals''', '''Ghubār numerals''',<ref>{{cite web |title=Arabic Numerals (Ghubar Numerals)|url=http://materiaislamica.com/index.php/Arabic_Numerals}}</ref>{{unreliable source?|date=September 2021}} '''Hindu-Arabic numerals''',{{Disputed inline|November 2021|date=November 2021}}{{sfn|Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered|2003|p=10}}<ref name="AHB">{{cite web|url=https://www.ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?id=A5414100|title=Arabic numeral|work=[[American Heritage Dictionary]]|date=2020|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company}}</ref><ref name="Britannica">{{cite encyclopedia|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hindu-Arabic-numerals|title=Hindu-Arabic numerals|encyclopedia=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]|date=2017|publisher=Britannica Group}}</ref> or '''[[ASCII]] digits'''.<ref>[https://www.unicode.org/terminology/digits.html Terminology for Digits]. Unicode Consortium.</ref> The ''[[Oxford English Dictionary]]'' uses lowercase ''Arabic numerals'' for them, and capitalized ''Arabic Numerals'' to refer to the [[Eastern Arabic numerals|Eastern digits]].<ref>"Arabic", ''Oxford English Dictionary'', 2nd edition</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

| Line 189: | Line 188: | ||

{{Div col end}} |

{{Div col end}} |

||

==Notes== |

|||

== Explanatory notes == |

|||

{{Notelist}} |

{{Notelist}} |

||

== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

{{Reflist|30em}} |

||

==Sources== |

|||

== General sources == |

|||

* {{citation |first=Paul |last= Kunitzsch |chapter=The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered |editor1=J. P. Hogendijk |editor2=A. I. Sabra |title=The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_AUtLNtg3nsC&pg=PA3 |year=2003 |publisher=MIT Press |isbn=978-0-262-19482-2 |pages=3–22 |ref={{sfnref|Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered|2003}}}} |

* {{citation |first=Paul |last= Kunitzsch |chapter=The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered |editor1=J. P. Hogendijk |editor2=A. I. Sabra |title=The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_AUtLNtg3nsC&pg=PA3 |year=2003 |publisher=MIT Press |isbn=978-0-262-19482-2 |pages=3–22 |ref={{sfnref|Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered|2003}}}} |

||

* {{citation |last=Plofker |first=Kim |author-link=Kim Plofker |title=Mathematics in India|title-link=Mathematics in India (book) |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-691-12067-6}} |

* {{citation |last=Plofker |first=Kim |author-link=Kim Plofker |title=Mathematics in India|title-link=Mathematics in India (book) |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-691-12067-6}} |

||

Revision as of 19:34, 28 December 2021

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

Arabic numerals are the ten numerical digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. These are by far the most commonly used symbols to write decimal numbers. They are also used for writing numbers in other bases such as octal, and for writing identifiers such as license plates.

The term often implies a decimal number, in particular when contrasted with Roman numerals. Decimal however was developed centuries before the Arabic numerals in the Asian subcontinent, using other symbols.

It was in the Algerian city of Bejaia that the Italian scholar Fibonacci first encountered the numerals; his work was crucial in making them known throughout Europe. European trade, books, and colonialism helped popularize the adoption of Arabic numerals around the world. The numerals have found worldwide use significantly beyond the contemporary spread of the Latin alphabet, intruding into the writing systems in regions where other numerals had been in use, such as Chinese and Japanese writing.

They are also called Western Arabic numerals, Ghubār numerals,[1][unreliable source?] Hindu-Arabic numerals,[disputed – discuss][2][3][4] or ASCII digits.[5] The Oxford English Dictionary uses lowercase Arabic numerals for them, and capitalized Arabic Numerals to refer to the Eastern digits.[6]

History

Origin of the Arabic numeral symbols

The reason the digits are more commonly known as "Arabic numerals" in Europe and the Americas is that they were introduced to Europe in the tenth century by Arabic speakers of Spain and North Africa, who were then using the digits from Libya to Morocco. In the eastern part of Arabic Peninsula, Arabs were using the Eastern Arabic numerals or "Mashriki" numerals: ٠ ١ ٢ ٣ ٤ ٥ ٦ ٧ ٨ ٩[a]

Al-Nasawi wrote in the early eleventh century that mathematicians had not agreed on the form of the numerals, but most of them had agreed to train themselves with the forms now known as Eastern Arabic numerals.[7] The oldest specimens of the written numerals available are from Egypt and date to 873–874 CE. They show three forms of the numeral "2" and two forms of the numeral "3", and these variations indicate the divergence between what later became known as the Eastern Arabic numerals and the Western Arabic numerals.[8] The Western Arabic numerals came to be used in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus from the tenth century onward.[9]

Calculations were originally performed using a dust board (takht, Latin: tabula), which involved writing symbols with a stylus and erasing them. The use of the dust board appears to have introduced a divergence in terminology as well: whereas the Hindu reckoning was called ḥisāb al-hindī in the east, it was called ḥisāb al-ghubār in the west (literally, "calculation with dust").[10] The numerals themselves were referred to in the west as ashkāl al‐ghubār ("dust figures") or qalam al-ghubår ("dust letters").[2] Al-Uqlidisi later invented a system of calculations with ink and paper "without board and erasing" (bi-ghayr takht wa-lā maḥw bal bi-dawāt wa-qirṭās).[11]

A popular myth claims that the symbols were designed to indicate their numeric value through the number of angles they contained, but no evidence exists of this, and the myth is difficult to reconcile with any digits past 4.[12]

Adoption in Europe

The first mentions of the numerals in the West are found in the Codex Vigilanus (aka Albeldensis) of 976.[13]

From the 980s, Gerbert of Aurillac (later, Pope Sylvester II) used his position to spread knowledge of the numerals in Europe. Gerbert studied in Barcelona in his youth. He was known to have requested mathematical treatises concerning the astrolabe from Lupitus of Barcelona after he had returned to France.[citation needed]

Leonardo Fibonacci (also known as Leonardo of Pisa), a mathematician born in the Republic of Pisa who had studied in Béjaïa (Bougie), Algeria, promoted the Indian numeral system in Europe with his 1202 book Liber Abaci:

When my father, who had been appointed by his country as public notary in the customs at Bugia acting for the Pisan merchants going there, was in charge, he summoned me to him while I was still a child, and having an eye to usefulness and future convenience, desired me to stay there and receive instruction in the school of accounting. There, when I had been introduced to the art of the Indians' nine symbols through remarkable teaching, knowledge of the art very soon pleased me above all else and I came to understand it.

The European acceptance of the numerals was accelerated by the invention of the printing press, and they became widely known during the 15th century. Early evidence of their use in Britain includes: an equal hour horary quadrant from 1396,[14] in England, a 1445 inscription on the tower of Heathfield Church, Sussex; a 1448 inscription on a wooden lych-gate of Bray Church, Berkshire; and a 1487 inscription on the belfry door at Piddletrenthide church, Dorset; and in Scotland a 1470 inscription on the tomb of the first Earl of Huntly in Elgin Cathedral.[15] In central Europe, the King of Hungary Ladislaus the Posthumous, started the use of Arabic numerals, which appear for the first time in a royal document of 1456.[16] By the mid-16th century, they were in common use in most of Europe.[17] Roman numerals remained in use mostly for the notation of anno Domini years, and for numbers on clockfaces.

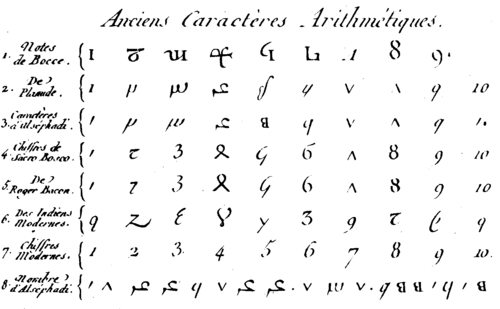

The evolution of the numerals in early Europe is shown here in a table created by the French scholar Jean-Étienne Montucla in his Histoire de la Mathematique, which was published in 1757:

Adoption in Russia

Cyrillic numerals were a numbering system derived from the Cyrillic alphabet, used by South and East Slavic peoples. The system was used in Russia as late as the early 18th century when Peter the Great replaced it with Arabic numerals.

Adoption in China

Positional notation was introduced to China during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) by the Muslim Hui people. In the early 17th century, European-style Arabic numerals were introduced by Spanish and Portuguese Jesuits.[18][19][20]

Encoding

The ten Arabic numerals are encoded in virtually every character set designed for electric, radio, and digital communication, such as Morse code.

They are encoded in ASCII at positions 0x30 to 0x39. Masking to the lower 4 binary bits (or taking the last hexadecimal digit) gives the value of the digit, a great help in converting text to numbers on early computers. These positions were inherited in Unicode.[21] EBCDIC used different values, but also had the lower 4 bits equal to the digit value.

| Binary | Octal | Decimal | Hex | Glyph | Unicode | EBCDIC (Hex) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0011 0000 | 060 | 48 | 30 | 0 | U+0030 DIGIT ZERO | F0 |

| 0011 0001 | 061 | 49 | 31 | 1 | U+0031 DIGIT ONE | F1 |

| 0011 0010 | 062 | 50 | 32 | 2 | U+0032 DIGIT TWO | F2 |

| 0011 0011 | 063 | 51 | 33 | 3 | U+0033 DIGIT THREE | F3 |

| 0011 0100 | 064 | 52 | 34 | 4 | U+0034 DIGIT FOUR | F4 |

| 0011 0101 | 065 | 53 | 35 | 5 | U+0035 DIGIT FIVE | F5 |

| 0011 0110 | 066 | 54 | 36 | 6 | U+0036 DIGIT SIX | F6 |

| 0011 0111 | 067 | 55 | 37 | 7 | U+0037 DIGIT SEVEN | F7 |

| 0011 1000 | 070 | 56 | 38 | 8 | U+0038 DIGIT EIGHT | F8 |

| 0011 1001 | 071 | 57 | 39 | 9 | U+0039 DIGIT NINE | F9 |

Comparison of different numerals

| Western Arabic | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Eastern Arabic[b] | ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ | ١٠ |

| Persian[c] | ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | ۱۰ |

| Urdu[d] | ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | ۱۰ |

| Abjad numerals | ا | ب | ج | د | ه | و | ز | ح | ط | ي |

See also

- Abjad numerals

- Chinese numerals

- Counting rods – decimal positional numeral system with zero

- Decimal

- Greek numerals

- Japanese numerals

- Maya numerals

- Regional variations in modern handwritten Arabic numerals

- Seven-segment display

- Text figures

Notes

- ^ Shown right-to-left, zero is on the right, nine on the left.

- ^ U+0660 through U+0669

- ^ U+06F0 through U+06F9. The numbers 4, 5, and 6 are different from Eastern Arabic.

- ^ Same Unicode characters as the Persian, but language is set to Urdu. The numerals 4, 6 and 7 are different from Persian. On some devices, this row may appear identical to Persian.

References

- ^ "Arabic Numerals (Ghubar Numerals)".

- ^ a b Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered 2003, p. 10.

- ^ "Arabic numeral". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2020.

- ^ "Hindu-Arabic numerals". Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica Group. 2017.

- ^ Terminology for Digits. Unicode Consortium.

- ^ "Arabic", Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition

- ^ Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered 2003, p. 7: "Les personnes qui se sont occupées de la science du calcul n'ont pas été d'accord sur une partie des formes de ces neuf signes; mais la plupart d'entre elles sont convenues de les former comme il suit."

- ^ Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered 2003, pp. 12–13: "While specimens of Western Arabic numerals from the early period—the tenth to thirteenth centuries—are still not available, we know at least that Hindu reckoning (called ḥisāb al-ghubār) was known in the West from the tenth century onward..."

- ^ Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Kunitzsch, The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Ifrah, Georges (1998). The universal history of numbers: from prehistory to the invention of the computer. Translated by David Bellos (from the French). London: Harvill Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 9781860463242.

- ^ "MATHORIGINS.COM_V". www.mathorigins.com.

- ^ "14th century timepiece unearthed in Qld farm shed". ABC News.

- ^ See G. F. Hill, The Development of Arabic Numerals in Europe, for more examples.

- ^ Erdélyi: Magyar művelődéstörténet 1-2. kötet. Kolozsvár, 1913, 1918

- ^ Mathforum.org

- ^ Helaine Selin, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures. Springer. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9.

- ^ Meuleman, Johan H. (2002). Islam in the era of globalization: Muslim attitudes towards modernity and identity. Psychology Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7007-1691-3.

- ^ Peng Yoke Ho (2000). Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Courier Dover Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-486-41445-4.

- ^ "The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0" (PDF). unicode.org. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Sources

- Kunitzsch, Paul (2003), "The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered", in J. P. Hogendijk; A. I. Sabra (eds.), The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives, MIT Press, pp. 3–22, ISBN 978-0-262-19482-2

- Plofker, Kim (2009), Mathematics in India, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6

Further reading

- Ore, Oystein (1988), "Hindu-Arabic numerals", Number Theory and Its History, Dover, pp. 19–24, ISBN 0486656209.

- Burnett, Charles (2006), "The Semantics of Indian Numerals in Arabic, Greek and Latin", Journal of Indian Philosophy, 34 (1–2), Springer-Netherlands: 15–30, doi:10.1007/s10781-005-8153-z, S2CID 170783929.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (Kim Plofker) (2007), "mathematics, South Asian", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 189 (4761): 1–12, Bibcode:1961Natur.189S.273., doi:10.1038/189273c0, S2CID 4288165, retrieved 18 May 2007.

- Hayashi, Takao (1995), The Bakhshali Manuscript, An ancient Indian mathematical treatise, Groningen: Egbert Forsten, ISBN 906980087X.

- Ifrah, Georges (2000), A Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to Computers, New York: Wiley, ISBN 0471393401.

- Katz, Victor J., ed. (20 July 2007), The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691114859.

External links

- Development of Hindu Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic

- History of Counting Systems and Numerals. Retrieved 11 December 2005.

- The Evolution of Numbers. 16 April 2005.

- O'Connor, J. J. and Robertson, E. F. Indian numerals. November 2000.

- History of the numerals