Draft:LifE Study: Difference between revisions

shorten sentences, sharpen text |

Submitting using AfC-submit-wizard |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|German panel study with 3 generations since 1979}} |

|||

{{Draft topics|stem}} |

|||

{{AfC topic|stem}} |

|||

{{AfC submission|||ts=20241021103550|u=DeoaD|ns=118}} |

|||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:Draft:LifE 3G Study}} |

{{DISPLAYTITLE:Draft:LifE 3G Study}} |

||

Revision as of 10:35, 21 October 2024

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 6 weeks or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 1,235 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

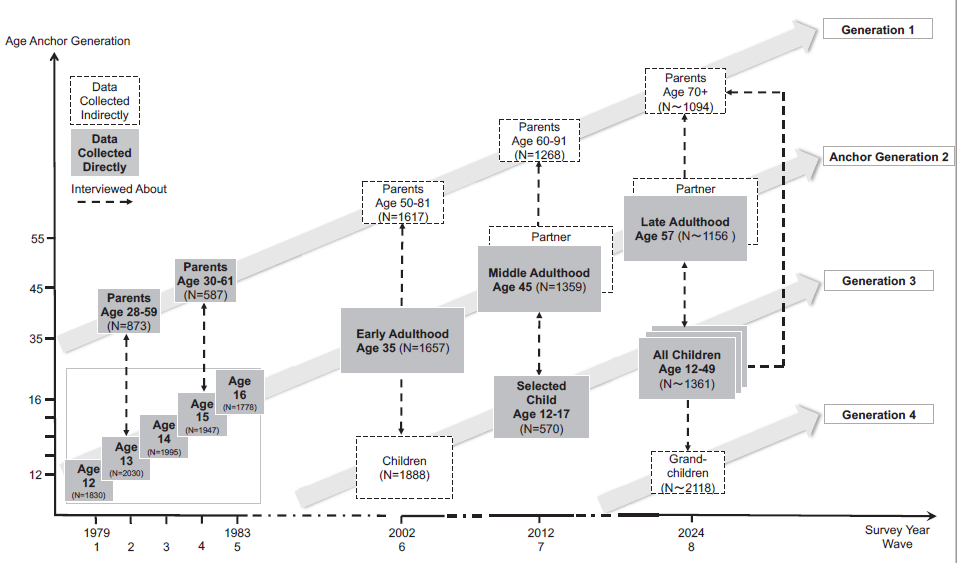

The LifE study (in German: Lebensverläufe ins frühe Erwachsenenalter or Lebensverläufe ins fortgeschrittene Erwachsenenalter; translated to English: ‘Life Paths into Early Adulthood’ or ‘Life Paths into Later Adulthood’) is a prospective German panel study ongoing since 1979. The study examines the individual development of approximately 1500 participants from Frankfurt (on the Main) and two rural regions in Hesse from the age of 12 onward in the context of familial relationships and various life domains across multiple life stages.

The LifE study contributes to life course research in the scientific fields of psychology, sociology, and the educational and pedagogical sciences. It examines life courses in changing historical and societal contexts in the areas of education and career, personality, and physical and mental health, as well as intergenerational relationships and the transmission of cultural, religious, and political orientations. Features of the LifE study with regard to basic research are the survey of different domains, and the investigation of three intra-family generations in a multi-actor approach.

The study is conducted collaboratively by scientists from the Universities of Potsdam, Innsbruck, and Zurich, including Helmut Fend, who established the study as the "Konstanzer Jugendstudie" (Konstanz Youth Study) at the University of Konstanz. The LifE study is and has been funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF).

| Current Management | Fred Berger, Wolfgang Lauterbach |

| Founder | Helmut Fend |

| Duration | Since 1979 (ongoing) |

| Participating Universities | University of Potsdam, University of Innsbruck, University of Zurich, University of Konstanz |

| Website in German | https://life3g.de |

History

The LifE Study originated from the Konstanz Youth Study. The Konstanz Youth Study, a longitudinal study, surveyed approximately 2000 children and adolescents born between 1962 and 1969 in Frankfurt (on the Main) and two rural regions in Hesse annually from 1979 to 1983; the parents were also included in the survey. The central focus was on psychological and social developmental trajectories during adolescence and the conditions for productive or impaired coping with age-specific developmental tasks.

LifE - Life Paths into Early Adulthood

In 2002/04, the now approximately 35-year-old former adolescents were surveyed again. 1657 individuals participated in the continuation study in adulthood after the long interruption. Various indicators of life coping were recorded in the social, professional, and cultural domains, as well as in the areas of mental and physical health. Assumptions about the long-term effects of certain protective and risk factors in adolescence were examined. Additional focuses were on the question of the continuity and discontinuity of developmental trajectories, as well as on predicting life coping in early adulthood.

Life Paths from Late Childhood into Later Adulthood

The seventh survey conducted in 2012 (the former adolescents were now 45 years old) expanded the study into a three-generation study, which now also included the children (G3) of the anchor generation (G2) in the survey.

LifE3G

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the eighth survey of the anchor generation (G2) (mid-50-year-olds) was postponed from 2022 to 2024. Under the title “LifE3G study”, the multi-actor and multi-generational approach will be expanded by surveying the entire generation of children of the anchor generation. These include the combination of latent growth processes and change-score models in adolescence with the growth processes in adulthood[1]. The survey supports the modeling of domain-specific as well as cross-domain developments and transitions from late childhood to later adulthood (ages 35, 45, and 57 years).

Study Design

The LifE Study is based on a long-term panel design. A cohort of children and adolescents born between 1965 and 1967 in Frankfurt (on the Main) and rural regions of Hesse (anchor generation G2) were surveyed annually from 1979 to 1983, as well as in 2002, 2012, and 2024 (planned). The sample is representative of the West German population at the end of the 1970s in terms of key socio-demographic indicators (e.g. marriage, number of children, income).

In the years 1980 and 1982, the parents of the anchor generation (G1) were also surveyed, and in 2012 and 2024 (planned), the children of the anchor generation (G3) were directly surveyed. Additionally, in 2024, the grandchildren of the anchor generation (G4) will be indirectly included in the study by asking the child generation (G3) questions about them. The response rate of the anchor generation in the long-term study at the ages of 35 and 45 years was approximately 85 percent each.

As three family generations are surveyed, it can be referred to as a multi-generational and multi-actor study. As a multi-domain study, the LifE Study collects data on four areas: "Education and Career", "Family and Partnerships", "Cultural, Religious, and Political Life Orientations", and "Personality and Health". In addition to prospective data, retrospective information was also collected to depict event-specific trajectories in the domains.

Theoretical Framework

Theories of human development across the lifespan have been of central importance since the beginning of the LifE study. The theoretical foundations of the adolescence study (1979–1983) were rooted in a socialization paradigm of growing up in various contexts. With the expansion of the study into early adulthood (Wave 2002, age 35), the framework evolved into a resource-based model of life management. In its third phase (Wave 2012, age 45), the project integrated the perspective of agency and structure, reflecting new interdisciplinary theoretical developments. These are based on both the sociological "life course theory"[2] and the psychological "life-span theory"[3].

Findings

Education and Career Domain

When considering educational and career trajectories, a result of the study is the early and high predictability of educational attainment and career paths from the age of twelve onward[4].

The validation of the meritocratic function of the education system was examined. For highly gifted children from lower social classes, it is evident that academic performance is the most significant factor determining the level of educational attainment. The reproductive function in the professional realm is particularly evident among children from higher social classes. Their educational careers are less dependent on cognitive competencies and more on social background.

Long-term effects of attending different types of schools and training programs on career paths were surveyed. In particular, the effect of "tracking," which is the assignment of children to different types of schools based on their performance in primary school, was examined. The hope of many experts and policymakers that integrated schools (comprehensive schools) would reduce educational inequality, as opposed to tracked schools, was not confirmed. The effect of later or minimized separation of students within integrated schools had no effect on the highest educational qualification obtained[5][6].

Many analyses of educational and career trajectories point to the different career paths of men and women. Income and status differences between men and women increase significantly with age[7]. Differences are particularly apparent after the child-raising phase. In international comparison with Canada, for example, it is especially evident that the majority of women who enter the workforce remain in the profession they were initially trained in for more than 20 years. In Canada, however, with a more open education system, it is shown that women in middle adulthood have pursued further education and obtained another degree, such as a bachelor's degree. The gender wage gap is lower in an education system that is permeable. The vocational system in Germany is very good for qualification in youth and young adulthood, but it inhibits the achievement of further qualifications[8][9].

Social Relationships

Despite certain changes in social relationships from late childhood to middle adulthood, there is also continuity and predictability in this area. The quality of early family relationship experiences and friendships in adolescence proves to be significant over the long term for the formation of partner relationships[10][11] and parent-child relationships in adulthood[12]. Close and secure relationships in early family life are important key factors for psychological well-being, emotional stability, and life satisfaction in adulthood[13]. They are significantly more important than educational and career trajectories. In this area, long-term unemployment and experiences of poverty in particular have an impact on mental health.

The study also describes social life trajectories and status transitions such as leaving the parental home, marriage, parenthood, and divorce as event histories and groups them using sequence analyses into patterns of social life trajectories[14][15][16]. There are clear gender-specific differences here. For example, mother-daughter relationships are shown to be the closest and most stable over the long term, and the predictive power of family relationship experiences is stronger for women over the long term than for men[17].

Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural, Religious, and Political Orientations

The home and school are identified as core determinants of cultural, religious, and political orientations in adulthood[18][19].

School proves to be a key institution for imparting refined cultural orientations that many children do not experience at home. Religious ties are almost exclusively formed through parental role models. The strength of value transmission depends significantly on the quality of intrafamilial communication[20]. Positive parent-child relationships and constructive parenting practices in childhood and adolescence are key factors for the intergenerational transmission of values and behaviors[21].

Personality and Health

Self-efficacy and self-esteem are considered central regulatory processes of agency in personality development analysis. Low self-esteem is specifically identified as a vulnerability factor[22] for the development of depression in early adulthood[23]. It is closely associated with the quality of relationships with parents and peers in adolescence, as well as with the closeness of relationships with partners and friends in adulthood[24].

In the thirty-year comparison of the educational and interpersonal climate in schools and families between the anchor generation (G2) and their children (G3) ages 12 to 16, social changes regarding respect and empathy for adolescents in schools and families are evident[25]. Thus, the LifE Study documents a crucial humanization of school education in the last three decades.

Project Researchers / Staff

1976–1984: H. Fend, R. Briechle (†), W. Endres (†), B. Fratz-Karremann, S. Gsching, A. Helmke, S. Hiller, W. Knörzer (†), U. Lauterbach, W. Nagl (†), H.-G. Prester, R. Raab, P. Richter, E. Schacher, C. Schellhammer, A. Schmidt, H. Schröder, S. Schröer, P. Schuler, W. Specht, M. Storch, R. Väth-Szusdziara

2000–2009: H. Fend, F. Berger, U. Grob, W. Lauterbach, W. Georg (†), J.-M. Bruggmann, L. Dommermuth, A. B. Erzinger, J. Glaesser, M. Jiménez, A. Sandmeier-Rupena, K. Stuhlmann, D. Looser, S. Givel

2009–2016: F. Berger, W. Lauterbach, H. Fend, W. Georg (†), U. Grob, K. Maag Merki, J. Gläßer, A. E. Grünefelder-Steiger, T. Heyne, S. Kaliga, J. Pehla, K. Schudel, M. Weil, J. Jung, A. Umhauer, J. Turgetto

2023-present: F. Berger, W. Lauterbach, H. Fend, U. Grob, S. Entrich, M. Floiger, S. Gadinger, L. Gleirscher, S. Glieber, W. Hagleitner, J. Jung, P. Nern, J. Turgetto[26][27].

Further Reading

- Entrich S., Lauterbach W.: Shadow education in Germany: Compensatory or status attainment strategy? Findings from the German LifE study. In: International Journal for Research on Extended Education. Volume 7(2), 2019, pp. 143–159, doi:10.3224/ijree.v7i2.04

- Fend H., Berger F., Grob U.: Life Courses, Life Management, Life Happiness: Results of the LifE Study. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, doi:10.1007/978-3-531-91547-0

- Harris L. M., Gruenenfelder-Steiger A. E., Ferrer E., Donnellan M., Allemand M., Fend H., Conger R., Trzesniewski K.: Do Parents Foster Self-Esteem? Testing the Prospective Impact of Parent Closeness on Adolescent Self-Esteem. In: Child Development. Volume 86(4), 2015, pp. 995–1013, doi:10.1111/cdev.12356

References

- ^ Hamaker, E. L.; Muthén, B. (2020). The fixed versus random effects debate and how it relates to centering in multilevel modeling. In: Psychological Methods. Vol. 25, No. 3, Juni 2020. pp. 365–379. doi:10.1037/met0000239. ISSN 1939-1463.

- ^ Elder, Glen H.; Johnson, Monica Kirkpatrick; Crosnoe, Robert (2003), Mortimer, Jeylan T.; Shanahan, Michael J. (eds.), "The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory", Handbook of the Life Course, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 3–19, doi:10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1, ISBN 978-0-306-47498-9, retrieved 2024-08-06

- ^ Baltes, P. B.; Lindenberger, U.; Staudinger, U. M. (2006). Life Span Theory in Developmental Psychology. In: W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (eds.): Handbook of Child Psychology. 6th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006. pp. 569–664. doi:10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0111.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Fend, H. (2014). Bildungslaufbahnen von Generationen: Befunde der LifE-Studie zur Interaktion von Elternhaus und Schule. In: Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft. Vol. 17, S2, März 2014. pp. 37–72. doi:10.1007/s11618-013-0463-4. ISSN 1434-663X.

- ^ Georg, W. (2016). Transmission of cultural capital and status attainment - an analysis of development between 15 and 45 years of age. In: Longitudinal and Life Course Studies. Vol. 7, No. 2, 28. April 2016. pp. 106–123. doi:10.14301/llcs.v7i2.341.

- ^ Lauterbach, W.; Fend, H. (2016). Educational mobility and equal opportunity in different German tracking systems – Findings from the LifE study. In: Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality. Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781785367267.00015. ISBN 978-1-78536-726-7.

- ^ Lauterbach, W. (2016). Educational capital and unequal income development over the life course. Society for longitudinal and life course studies (SLLS), Bamberg, 5.-8.10.2016.

- ^ Andres, L.; Lauterbach, W.; Jongbloed, J.; Hümme, H. (2021). Gender, education, and labour market participation across the life course: A Canada/Germany comparison. In: International Journal of Lifelong Education. Vol. 40, No. 2, 4. March 2021. pp. 170–189. doi:10.1080/02601370.2021.1924302. ISSN 0260-1370.

- ^ Kaliga, S. N. (2018). Eine Frage der Zeit. Wie Einflüsse individueller Merkmale auf Einkommen bei Frauen über ihre familiären Verpflichtungen vermittelt werden. Eine Untersuchung mit den Daten der LifE-Studie. Universität Potsdam.

- ^ Jung, J. (2021). Does youth matter? Long-term effects of youth characteristics on the diversity of partnership trajectories. In: Longitudinal and Life Course Studies. Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2021. pp. 201–225. doi:10.1332/175795920X15980339169308. ISSN 1757-9597.

- ^ Umhauer, A. (2020). Die Bedeutung von Beziehungserfahrungen und Beziehungsvorstellungen in der Adoleszenz für Paarbeziehungen im Erwachsenenalter. Universitat Innsbruck.

- ^ Berger, F.; Fend, H. (2005). Kontinuität und Wandel in der affektiven Beziehung zwischen Eltern und Kindern vom Jugend- bis ins Erwachsenenalter. doi:10.25656/01:5663. ISSN 0720-4361.

- ^ Schudel, K. (2016). Long term trait and state effects of self-esteem and social integration on satisfaction. SLLS Annual International Conference, Bamberg, 6.-8.10.2016.

- ^ Berger, F. (2009). Intergenerationale Transmission von Scheidung – Vermittlungsprozesse und Scheidungsbarrieren. In: Lebensverläufe, Lebensbewältigung, Lebensglück. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009. pp. 267–303. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-91547-0_10. ISBN 978-3-531-15352-0.

- ^ Gläßer, J.; Lauterbach, W.; Berger, F. (2018). Predicting the Timing of Social Transitions from Personal, Social and Socio-Economic Resources of German Adolescents. Comparative Population Studies. Vol. 43, 12. December 2018. doi:10.12765/CPoS-2018-11. ISSN 1869-8999.

- ^ Jung, J. (2023). Partnership trajectories and their consequences over the life course. Evidence from the German LifE Study. In: Advances in Life Course Research. Vol. 55, 1. March 2023. doi:10.1016/j.alcr.2022.100525. ISSN 1569-4909.

- ^ Berger, F. (2008). Kontinuität und Wandel intergenerationaler Beziehungen von der späten Kindheit bis ins Erwachsenenalter. Universität Zürich.

- ^ Berger, F.; Grob, U. (2007). Jugend und Politik: Eine verständliche aber nur vorübergehende Kluft? Politische Sozialisation im Jugendalter und ihre Folgen für politische Haltungen im Erwachsenenalter. In: H. Biedermann, F. Oser, & C. Quesel (eds.): Vom Gelingen und Scheitern Politischer Bildung. Studien und Entwürfe. Zürich u.a., Rüegger Verlag. pp. 109–140.

- ^ Grob, U. (2010). Der Beitrag der Schule zur Entwicklung von politischem Interesse und Toleranz im Spiegel der LifE-Studie. Fachvortrag gehalten im Rahmen des Kongresses „Bildung in der Demokratie“ der DGFE, Mainz.

- ^ Grob, U. (2016). Intergenerational Transmission of Political Orientations. SLLS-Conference, Bamberg, 6.-8.10.2016.

- ^ Berger, F. (2016). Wertetransmission von Eltern zu Kindern. Zur »Vererbung« von Einstellungen und Überzeugungen in Zeiten sozialen Wandels. In: Schüler: Wissen für Lehrer. Heft zum Thema Werte. DIPF, Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsforschung und Bildungsinformation, Frankfurt am Main, 2016. pp. 56–61. ISSN 0949-2852.

- ^ Harris, M. A.; Orth, U. (2020). The link between self-esteem and social relationships: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. In: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Vol. 119, No. 6, December 2020. pp. 1459–1477. doi:10.1037/pspp0000265. ISSN 1939-1315.

- ^ Steiger, Andrea E.; Allemand, M.; Robins, R. W.; Fend, H. (2014). Low and decreasing self-esteem during adolescence predict adult depression two decades later. In: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Vol. 106, No. 2, 2014. pp. 325–338. doi:10.1037/a0035133. ISSN 1939-1315.

- ^ Steiger, Andrea E.; Fend, H.; Allemand, M. (2015). Testing the vulnerability and scar models of self-esteem and depressive symptoms from adolescence to middle adulthood and across generations. In: Developmental Psychology. Vol. 51, No. 2, February 2015.

- ^ Fend, H.; Berger, F. (2016). Ist die Schule humaner geworden? Sozialhistorischer Wandel der pädagogischen Kulturen in Schule und Familie in den letzten 30 Jahren im Spiegel der LifE-Studie. In: Zeitschrift für Pädagogik. Vol. 62, No. 6, 2016. pp. 861–885. ISSN 0044-3247.

- ^ "Management team - LifE3G". LifE3G (in German). Retrieved 2024-01-08.

- ^ "Research team - LifE3G". LifE3G (in German). Retrieved 2024-01-08.