Griffin: Difference between revisions

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

|}}</ref> It is not yet clear if its forelimbs are those of an eagle or of a lion. Although the description implies the latter, the accompanying illustration is ambiguous. It was left to the heralds to clarify that. pink |

|}}</ref> It is not yet clear if its forelimbs are those of an eagle or of a lion. Although the description implies the latter, the accompanying illustration is ambiguous. It was left to the heralds to clarify that. pink |

||

YES!!! PWNED :D purple.. |

|||

==In heraldry== |

|||

[[Image:Armoirie.griffon.png|thumb|right|222px|A heraldic griffin, from ''Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle'' by [[Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc]] (1856)]] |

|||

[[Image:GRIFEO stemma del Laurana Castello Partanna.jpg|thumb|right|222px|Heraldic griffin, made by Francesco Laurana (1468), sculptor. From Grifeo's Castle, [[Partanna]] ([[Trapani]]), [[Sicily]] - [[Italy]]]] |

|||

The griffin is often seen as a [[Charge (heraldry)|charge]] in [[heraldry]]. According to the ''Tractatus de armis'' of [[John de Bado Aureo]] (late fourteenth century), ''"A griffin borne in arms signifies that the first to bear it was a strong pugnacious man in whom were found two distinct natures and qualities, those of the eagle and the lion."'' Since the lion and the eagle were both important charges in heraldry, it is perhaps unsurprising that their combination, the griffin, was also a frequent choice. |

|||

Bedingfeld and Gwynn-Jones suggest a far more bellicose reason for its choice as a charge: That because of the bitter antipathy between griffins and horses, a griffin borne on a shield would instill fear in the horses of his opponents. They also note the first appearance of the griffin in English heraldry, in a 1167 seal of Richard de Redvers, [[Earl of Essex]].<ref name="bedingfeld" /> (However, other writers quote later dates for its first appearance.<ref name="woodcock" /><ref name="friar" />) |

|||

The heraldic griffin establishes the contemporary depiction of the beast: Parker says, ''"The lower part of its body, with the tail and the hind-legs, belong to the lion; the head and the fore-part, with the legs and talons, to those of the eagle, but the head retains the ears of the lion. It has large wings, which also closely resemble those of the eagle."''<ref name="parker">{{cite book |

|||

|last=Parker |

|||

|first=James |

|||

|authorlink=James Parker |

|||

|title=A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry |

|||

|year=1894 |

|||

|publisher=James Parker & Co. |

|||

|location=Oxford |

|||

|}}: [http://www.heraldsnet.org/saitou/parker/Jpglossg.htm#Griffin Griffin]</ref> (The variant with the forelimbs of a lion is distinguished as the opinicus, described below.) |

|||

Heraldic griffins are usually shown rearing up, facing [[dexter]] (to the right of the bearer of the shield)*, standing on one hind leg with the other hind leg and both forelegs raised (as shown in the image on the right and those in the gallery below). This posture is described in the Norman-French heraldic [[blazon]] as ''segreant'', a term usually applied only to griffins (but sometimes also to dragons<ref name="von volborth" />). The generic term for this posture, used to describe lions and other beasts, is ''rampant''. |

|||

A griffin's head is also seen as a charge in its own right, and it is distinguished from an eagle's head solely by its ears (see the Kartuzy and Filisur arms in the gallery below). |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

Image:griffin3.jpg|<center>Medieval figure of a heraldic griffin |

|||

|<center>Badge of [[Gray's Inn]], one of the four [[Inns of Court]] |

|||

Image:POL_Słupsk_COA_1.svg|<center>Arms of [[Słupsk]], [[Poland]] |

|||

Image:POL_Białogard_COA_1.svg|<center> Arms of [[Białogard]], [[Poland]] |

|||

Image:Blason Saint-Brieuc.svg|<center>Arms of [[Saint-Brieuc]], [[France]] |

|||

Image:Wappen_Greifswald.svg|<center>Arms of [[Greifswald]], [[Germany]] |

|||

Image:Kleines Stadtwappen Ueckermünde.svg|<center>Arms of [[Ueckermünde]], [[Germany]] |

|||

Image:Wappen Pommern.svg|<center>Arms of [[Hither Pomerania]], [[Germany]] |

|||

Image:Coat of arms of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (great).svg|<center>Arms of [[Mecklenburg-Vorpommern]], [[Germany]] |

|||

Image:Rostock Wappen.svg|<center>Arms of [[Rostock]], [[Germany]] |

|||

Image:POL województwo zachodniopomorskie COA.svg|<center>Arms of [[West Pomeranian Voivodeship]], [[Poland]] |

|||

Image:MecklbgSchw.jpg|<center>Arms of [[Mecklenburg-Schwerin]] |

|||

Image:Wappen Deutsches Reich - Grossherzogtum Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Grosses).jpg|<center>Arms of [[Mecklenburg-Strelitz]] |

|||

Image:Södermanland vapen.svg|<center>Arms of [[Södermanland]], [[Sweden]] |

|||

Image:Donath wappen.svg|<center>Arms of the former municipality of [[Donat, Switzerland|Donath]], [[Switzerland]] |

|||

Image:Montepulciano-Stemma.png|<center>Arms of [[Montepulciano]], [[Italy]] |

|||

<!-- Image with inadequate rationale removed: Image:Logocomuneperugia.png|<center>Arms of [[Perugia]], Italy --> |

|||

Image:Deruta-Stemma.gif|<center>Arms of [[Deruta]], Italy |

|||

Image:Volterra-Stemma.png|<center>Arms of [[Volterra]], Italy |

|||

Image:Coat_of_Arms_of_Troms.svg|<center>Arms of [[Troms]], [[Norway]] |

|||

Image:Sayansk coat of arms.jpg|<center>Arms of [[Sayansk]], [[Russia]] |

|||

Image:UtJR flag.gif|<center>Colour of [[Utti Jaeger Regiment]], [[Finnish Army]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

;Griffin head as a charge |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

Image:POL_Kartuzy_COA.svg|<center>Arms of [[Kartuzy]], [[Poland]] |

|||

Image:POL Szczecin COA.svg|<center>Arms of [[Szczecin]], [[Poland]] |

|||

Image:Filisur wappen.svg|<center>Arms of [[Filisur]], [[Switzerland]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

;Griffin as a supporter |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

Image:Grosses Landeswappen Baden-Wuerttemberg.png|<center>[[Coat of arms of Baden-Württemberg|Arms of Baden-Württemberg]], [[Germany]] |

|||

Image:Stralsund, Germany, Rathaus, Schwedenwappen (2006-09-29).png|<center>Arms of [[Stralsund]], [[Germany]] |

|||

Image:Genova-Stemma.png|<center>Arms of [[Genoa]], Italy |

|||

Image:Coat of Arms of Latvia.svg|<center>[[Coat of arms of Latvia|Arms of Latvia]] |

|||

Image:Austria-Hungaria transparency.png|<center>Arms of [[Austria-Hungary]](1915-18) |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

A heraldic griffin was included as one of the ten [[Queen's Beasts]] sculpted for the coronation of [[Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom|Queen Elizabeth II]] in 1953 (following the model of the King’s Beasts at Hampton Court) and this is now on display at [[Kew Gardens]]. |

|||

===Male griffin, alce or keythong=== |

|||

Parker says, of the griffin, ''"It may be represented as without wings, and then with rays or spikes of gold proceeding from several parts of its body. Sometimes it has two long straight horns. The term Alce is given, as if used by writers for a kind of griffin, but no example can be quoted."'' <ref name="parker" /> |

|||

But the term '''alce''' is rare in modern heraldry reference books; this wingless, spiked variant is almost invariably called the '''male griffin''' - although this must be a very unusual case of [[dimorphism]] because, as Stephen Friar puts it, ''"both creatures possess the usual male attributes"''.<ref name="friar" /> |

|||

The male griffin itself is quite rare. It occurs as the dexter supporter (to the right of the bearer of the shield/ to the left of the viewer) in the arms of St. Leger entered at the visitation of Devon and Cornwall 1531 (College of Arms G 2, folio 24v) and as the supporter of the banner of a mid-16th-century [[Knight]] of the [[Order of the Garter|Garter]] in College of Arms Vincent 152 (pp 107-8). <ref name="woodcock">{{cite book |

|||

|last=Woodcock |

|||

|first=Thomas |

|||

|authorlink=Thomas Woodcock (officer of arms) |

|||

|coauthors=[[John Martin Robinson|Robinson, John Martin]] |

|||

|title=The Oxford Guide to Heraldry |

|||

|pages=p 100 & plate 19 |

|||

|year=1988; pb 1990 |

|||

|publisher=Oxford Paperbacks/[[Oxford University Press]] |

|||

|location=Oxford |

|||

|isbn=0192852248 |

|||

|}} </ref> In the late 19th century, Sir Henry William Dashwood was granted supporters: ''two male griffins Argent [white] gorged with a collar [[Fleur-de-lis|flory counter flory]]''.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|last=Bedingfeld |

|||

|first=Henry |

|||

|authorlink=Henry Bedingfeld (officer of arms) |

|||

|coauthors=[[Peter Gwynn-Jones|Gwynn-Jones, Peter]] |

|||

|title=Heraldry |

|||

|year=1993 |

|||

|pages=p 71 |

|||

|location=Wigston |

|||

|publisher=Magna Books |

|||

|isbn=1854224336 |

|||

|}}</ref> One was also recently granted as a crest in the arms of the City of [[Melfort, Saskatchewan]] ([http://mlfrtqlx.sasktelwebhosting.com/pdf/crest.pdf image]).<ref> [http://www.cityofmelfort.ca/ City of Melfort Website]</ref> |

|||

The term '''keythong''' is rarer still. The definitive instance comes from [[James Planché]], who notes, under the badge of the [[Earl of Ormonde]] (first creation) as recorded in a [[College of Arms]] manuscript from the reign of [[Edward IV of England|Edward IV]], the single contemporary reference: ''"A pair of keythongs."'' Planche's footnote: ''"The word is certainly so written, and I have never seen it elsewhere. The figure resembles the Male Griffin, which has no wings, but rays or spikes of gold proceeding from several parts of his body, and sometimes with two long straight horns. Vade [see] Parker's Glossary, under Griffin."'' |

|||

<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|last=Planché |

|||

|first=J. R. |

|||

|authorlink=James Planché |

|||

|title=Pursuivant of Arms |

|||

|year=1859 |

|||

|location=London |

|||

|}} Source: [http://www.sca.org/heraldry/loar/1986/05/cvr.html Society of Creative Anachronism website]</ref> |

|||

At the end of the 20th century the term ''keythong'' began to be taken up enthusiastically among adherents of heraldry - at least, among members of the [[Society for Creative Anachronism]]. |

|||

===Opinicus=== |

|||

[[Image:Opinicus.gif|thumb|right|222px|right|An opinicus statant (standing on four feet)]] |

|||

The '''opinicus''' is a heraldic beast that differs from the griffin principally in that all four of its legs are those of a lion.<ref name="friar" /> It is typically shown with the short tail of a [[camel]] and sometimes with a longer neck like a camel's (but still feathered). An heraldic opinicus is shown as a male creature, whereas the winged griffin is female. |

|||

However, Parker says, ''"[it] is allied more nearly to the dragon in the forepart and in the wings; but it has a beaked head and ears, something between the dragon and the griffin. The hind part and the four legs are probably intended to represent those of a lion, but the tail is short, and is said to be that of the camel."''<ref name="parker" /> |

|||

It was granted as a crest in 1561 to [[City of London]]'s Company of Barber Surgeons (now the Worshipful Company of Barbers)<ref name="friar" /><ref>[http://www.barberscompany.org.uk/opinicus.htm The Opinicus]</ref>, but is otherwise rare in British heraldry. A modern example can be found in the arms of Jonathan Munday: ''Azure an opinicus rampant Or armed Gules''.<ref>[http://www.theheraldrysociety.com/resources/jonathonmunday.htm The Heraldry Society - members' arms]: Jonathan Munday</ref> |

|||

(Note that it is described as ''rampant'' rather than ''segreant''.) |

|||

===Other oddities=== |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

Image:Östergötland_coat_of_arms.png|<center>Arms of [[Östergötland]], [[Sweden]] |

|||

Image:Pommern_1563.jpg |<center>Arms of the [[Duchy]] of [[Pomerania]] |

|||

Image:Grifeo stemma.jpg|<center>Arms of Grifeo's Family, [[Prince]] of [[Partanna]], [[Sicily]], [[Italy]]<br /> |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

* The "griffin" in the arms of [[Östergötland]] has [[dragon]]'s wings. This is essentially a composite of two older arms, one charged with a lion, the other a dragon. |

|||

* The arms of the [[Duchy of Pomerania]] features several typical griffins. However, the white "griffin" in the gules (red) dexter fess (middle right) piece has a [[fish]]'s tail - only its lion's ears confirm that it's a fish-tailed griffin rather than a fish-tailed eagle. |

|||

===Similar heraldic beasts=== |

|||

The following heraldic beasts are not griffins, but might be mistaken for them. |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

<!-- Image with unknown copyright status removed: Image:citylondonarms.jpg|<center>'''[[Dragon]]''' supporters of the arms of the [[City of London]] --> |

|||

Image:Lostallo wappen.svg|<center>A '''winged [[lion]]''' in the arms of [[Lostallo]], [[Switzerland]] |

|||

Image:Provincia di Grosseto-Stemma.png|<center>A '''winged lion''' in the arms of the [[Province of Grosseto]], Italy |

|||

Image:MI5_logo.png|<center>A '''winged sea-lion''' in the badge of [[MI5]], [[UK]] {{deletable image-caption|1={{subst:#time:l, j F Y| + 7 days}}}} |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

* The [[cockatrice]], the king of the serpents, has a [[rooster]]'s head, only two legs (rather like an eagle's or dragon's), dragon's wings, and a serpent's tail.<ref name="friar" /> |

|||

* The dragon supporters of the arms of [[City of London]], including the single statues holding the arms that stand in each road leading into the City of London to mark its boundaries, are frequently misidentified as griffins. A heraldic dragon has a scaly body, membranous wings, no feathers and no eagle's beak. |

|||

* A winged lion is the symbol of Saint [[Mark the Evangelist]]. |

|||

==In architecture== |

==In architecture== |

||

Revision as of 16:44, 17 October 2008

The griffin is a legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head and often wings of an eagle. As the lion was traditionally considered the king of the beasts and the eagle the king of the birds, the griffin was thought to be an especially powerful and majestic creature. Griffins are normally known for guarding treasure.[1] In antiquity it was a symbol of divine power and a guardian of the divine.[2]

Most contemporary illustrations give the griffin the forelegs of an eagle, with an eagle's legs and talons, although in some older illustrations it has a lion's forelimbs; it generally has a lion's hindquarters. Its eagle's head is conventionally given prominent ears; these are sometimes described as the lion's ears, but are often elongated (more like a horse's), and are sometimes feathered.

Infrequently, a griffin is portrayed without wings (or a wingless eagle-headed lion is identified as a griffin); in 15th-century and later heraldry such a beast may be called an alce or a keythong. In heraldry, a griffin always has forelegs like an eagle's hind legs; the beast with forelimbs like a lion's forelegs was distinguished by perhaps only one English herald of later heraldry as the opinicus; the word "opinicus" escaped the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary. The modern generalist calls it the lion-griffin, as for example, Robin Lane Fox, in Alexander the Great, 1973:31 and notes p. 506, who remarks a lion-griffin attacking a stag in a pebble mosaic at Pella, perhaps as an emblem of the kingdom of Macedon or a personal one of Alexander's successor Antipater.

After "griffin", the spelling gryphon is the most common variant in English, gaining popularity following the publication of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland as can be observed from usage in The Times and elsewhere. Less common variants include gryphen, griffen, and gryphin.; from Latin grȳphus, from Greek γρύψ gryps, from γρύπος grypos hooked. The spelling "griffon" (from Middle English and Middle French) was previously frequent but is now rare, probably to avoid confusion with the breed of dog called a griffon.

History

Ancient Near East

This article needs attention from an expert in Ancient Near East. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. |

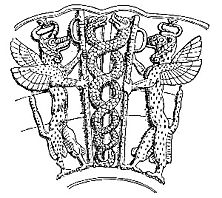

Several griffin-like creatures - beasts with the head of an eagle or some other bird of prey - occur in art, architecture and mythology of many early civilizations.

Of the two sacred "birds" of Persian mythology, the homa and the simurgh, the homa is often described as griffin-like. Ancient Elamites used such a creature extensively in their architecture. During the Achaemenid Empire, homa were used widely as statues and symbols in palaces. Homa also had a special place in Persian literature as guardians of light. [citation needed]

In Ancient Egypt, a similar creature was depicted with a slender, feline body and the head of a falcon; this is tentatively identified as an axex.[3] Early statuary depicts them with wings that are horizontal and parallel along the back of the body. During the New Kingdom, depictions of griffins included hunting scenes. [citation needed]

In Minoan Crete, such creatures were royal animals and guardians of throne rooms. [4]

Scythia

The griffin was a common feature of "animal style" Scythian gold. It was said to inhabit the Scythian steppes that reached from the modern Ukraine to central Asia; there gold and precious stones were abundant and when strangers approached to gather the stones, the creatures would leap on them and tear them to pieces. The Scythians used giant petrified bones found in this area as proof of the existence of these griffins and thus keep outsiders away from the gold and precious stones.

Adrienne Mayor, a classical folklorist, has recently suggested that these "griffin bones" were actually dinosaur fossils, which are common in this part of the world. In The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times, she makes tentative connections between the rich fossil beds around the Mediterranean and across the steppes to the Gobi Desert and the myths of griffins, centaurs and archaic giants originating in the Classical world. Mayor draws upon similarities that exist between the griffin and the prehistoric Protoceratops skeletons of the steppes leading to the Gobi Desert, and the legends of the gold-hoarding griffin told by nomadic Scythians of the region.[5]

Ancient Greece

|

|

In archaic Greek art bronze cauldrons fitted with apotropaic bronze griffon heads ("protomes") with gaping beaks, prominent upstanding ears and often a finial knop on the skull appear with such regularity that they are considered a genre, the Griefenkessel, by specialists. The "griffin cauldrons" are discussed by Ulf Jantzen, Griechische Griefenkessel (Berlin) 1955. Based on Anatolian prototypes for bronze cauldrons with animal heads, Jantzen concluded that the griffon cauldron was a Greek invention of c.700 BC, the earliest examples hammered over moulds rather than cast. Such griffon cauldrons were developed simultaneously in Samos and in Etruscan territories from the earliest 7th through the 6th centuries BC. The earliest Etruscan example is the famous griffon protomes from the Barberini Tomb.[6]

In Greek literature, Scythian mythology is reflected by Hellenic writers' tales of griffins and the Arimaspi of distant Scythia near the cave of Boreas, the North Wind (Geskleithron), such as were elaborated in the lost archaic poem of Aristeas of Proconnesus (7th century BC), Arimaspea. Bedingfeld and Gwynn-Jones infer that Aristeas's griffin was, "the bearded vulture or lammergeyer, a huge bird with a wingspan of nearly three metres (ten feet), which nests in inaccessible cliffs in the Asiatic mountains. ... The gold of the region is real enough and is still mined today." They also suggest that Aristeas conflated the Scythian griffin with a similar creature - a composite of lion and eagle or lion and griffon vulture - already known to Greek culture. [7]

In any case, Aristeas's tales were eagerly reported by Herodotus (484 BC–c.425 BC) and in Pliny the Elder's Natural History (77 AD), among others. Aeschylus (525–456 BC), in Prometheus Bound (804), has Prometheus warn Io: "Beware of the sharp-beaked hounds of Zeus that do not bark, the gryphons..."[8] In his Description of Greece (1.24.6), Pausanias (2nd century AD) says, "griffins are beasts like lions, but with the beak and wings of an eagle."[8] The griffin was said to build a nest, like an eagle: instead of eggs, it lays sapphires, and thus griffins are supposed to be female. The animal was supposed to watch over gold mines and hidden treasures, and to be the enemy of the horse. The consequently rare offspring of griffin and horse was called a hippogriff.

Stephen Friar notes that the griffin was regarded as an animal of the sun and pulled Apollo's chariot across the sky; but it pulled Nemesis's chariot too.[1]

|

|

The lion-griffin appears on coins of Alexander's general and successor Antipater upon his arrival in Syria in 321/20 BCE.[9]

Medieval lore

A 9th-century Irish writer by the name of Stephen Scotus asserted that griffins were strictly monogamous. Not only did they mate for life, but if one partner died, the other would continue throughout the rest of its life alone, never to search for a new mate. The griffin was thus made an emblem of the Church's views on remarriage.

Being a union of a terrestrial beast and an aerial bird, it was seen in Christianity to be a symbol of Jesus Christ, who was both human and divine. As such it can be found sculpted on churches.[1]

According to Stephen Friar, a griffin's claw was believed to have medicinal properties and one of its feathers could restore sight to the blind.[1] Goblets fashioned from griffin claws (actually antelope horns) and griffin eggs (actually ostrich eggs) were highly prized in medieval European courts.[7]

By the 12th century the appearance of the griffin was substantially fixed: "All its bodily members are like a lion's, but its wings and mask are like an eagle's."[10] It is not yet clear if its forelimbs are those of an eagle or of a lion. Although the description implies the latter, the accompanying illustration is ambiguous. It was left to the heralds to clarify that. pink

YES!!! PWNED :D purple..

In architecture

In architectural decoration the griffin is usually represented as a four-footed beast with wings and the head of a leopard or tiger with horns, or with the head and beak of an eagle.[citation needed]

The griffin is the symbol of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and you can see bronze castings of them perched on each corner of the museum's roof, protecting its collection.[11][12]

In literature

- For fictional characters named Griffin, see Griffin (surname)

- John Milton, in Book II of Paradise Lost, refers to the legend of the griffin in describing Satan:

As when a Gryfon through the Wilderness

With winged course ore Hill or moarie Dale,

Pursues the ARIMASPIAN, who by stelth

Had from his wakeful custody purloind

The guarded Gold [...]

- Griffins are used widely in Persian poetry. Rumi is one such poet who writes in reference to griffins (for example, in The Essential Rumi, translated from Persian by Coleman Barks, p 257).

- In Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy, a griffin pulls the chariot which brings Beatrice to Dante in Canto XXIX of the Purgatory.

- In Voltaire's La Princesse de Babylone (The Princess of Babylon; 1768), two griffins transport princess Formosante.

- Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), the Queen of Hearts orders the Gryphon to take Alice to see the Mock Turtle and hear its story.

- In L. Frank Baum's The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904) the evil witch Old Mombi transforms herself into a griffin to escape from the good witch Glenda.

- Although no Gryphons are referenced in C. S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia, the movie, "The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe" portrays a griffin,

- In T. H. White's The Once and Future King (1958), young Arthur and his stepbrother Kay battle a fierce griffin with aid from Robin Wood A.K.A. Robin Hood soon after freeing captives of Morgan le Fay.

- In Geoff Ryman's The Warrior Who Carried Life (1980), a huge, white griffin know as "The Beast Who Talks to God" is one of the major characters.

- In the Dragonlance series (1984 onwards), griffins are under the command of Silvanesti Elves.

- In Neil Gaiman's Sandman comic book series (1988-1996), a griffin is one of three guardians of Morpheus's palace in The Dreaming.

- In Mercedes Lackey and Larry Dixon's The Mage Wars Trilogy - The Black Gryphon (1994), The White Gryphon (1995) and The Silver Gryphon (1996) - gryphons known as Skandranon, and, later, his son Tadrith are among the lead characters. In this series gryphons have human level intelligence and can use magic.

- Griffins are among the magical creatures in J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series (1997-2007). Harry Potter's house at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry is called Gryffindor after its founder Godric Gryffindor. Fans have speculated that "Gryffindor" may come from the French gryffon d'or (golden griffin)[citation needed], but, oddly, its emblem is not a griffin, but a lion - which represents the supposed courageous nature of a true Gryffindor. In the movie versions, the gargoyle guarding the headmaster's office is depicted as a half-phoenix, half-lion griffin and the door-knocker is a griffin.

- In Tamora Pierce's Squire, part of the Protector of the Small quaret, the main character Kel stumbles upon a baby griffin kidnapped from his parents and is forced to care for him until they can be found.

- In Patricia McKillip's Song for the Basilisk (1998), a griffin is one of the book's main characters and appears as a symbol of the ruling house.

- In Bruce Coville's Song of the Wanderer (1999), the second book of The Unicorn Chronicles series, a gryphon named Medafil is a character.

- In Wilanne Schneider Belden's Frankie! (1987), a human baby turns into a griffin.

- In Collinsfort Village by Joe Ekaitis (2005), a gentlemanly griffin resides on a mountain overlooking an imaginary Colorado suburb.

- In Bill Peet's The Pinkish Purplish Bluish Egg (1984) a dove finds an odd egg, and raises the griffin that hatches from it. The griffin has the head of a bald eagle rather than the more usual golden eagle.

- In Katherine Robert's "The Amazon Temple Quest" a gryphon is connected with the Amazons and it is the one to give them power and to give them the ability to reproduce without men.

(unknown dates)

- In Nick O'Donohoe's Crossroads series (including The Magic and the Healing, Under the Healing Sign, and Healing of Crossroads) about veterinary students called upon to help mythological creatures, griffins play a significant role.

- In James C. Christianson's Voyage of the Basset, a griffon saves Casandra from the trolls.

- In The Spiderwick Chronicles, Simon Grace, Jared Grace's twin brother, befriends a wounded Griffin and names it Byron.

In natural history

Some large species of Old World vultures are called gryphons, including the griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus), as are some breeds of dog (griffons).

The scientific species name for the Andean Condor is Vultur gryphus; Latin for "griffin-vulture".

The name of an oviraptoran dinosaur Hagryphus giganteus is Latin for "gigantic Ha's Griffin".

As a first name and surname

In the mid-1990s, "Griffin" steadily became more popular as a baby name for boys in the U.S. In 1990, it was ranked 629th. In 2006, it was ranked 254th. Also rising in popularity is the various other spellings of the name such as Griffen or Gryphon.

"Griffin" occurs as a surname in English-speaking countries. It has its origins as an anglicised form of the Irish "Ó Gríobhtha", "O' Griffin", and "Ó Griffey".

Welsh people who were anglicised, changed the name to "Griffith" and similar names. This shift is reinforced where the family has taken canting arms charged with a griffin.

"Griffin" (and variants in other languages) may also have been adopted as a surname by other families who used arms charged with a griffin or a griffin's head (just as the House of Plantagenet took its name from the badge of a sprig of broom or planta genista). This is ostensibly the origin of the Swedish surname "Grip" (see main article).

Other

Westminster College in Salt Lake City, Utah holds the mascot of the Griffin

University of Guelph in Guelph, Ontario holds the mascot of the Gryphon

Canisius College in Buffalo, New York holds the mascot of the Griffin [1]

The now-defunct Kennedy High School in Willingboro, New Jersey held the mascot of the Gryphon.

Persian firstname

The creature griffin is known as Homa in Persian. The name Homa is a well-known firstname for girls in Iran and is also featured as a story in Iranian textbooks for third graders in the story about Homa who has lost one of her milkteeth.

Notes and references

- ^ a b c d Friar, Stephen (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Alphabooks/A & C Black. pp. p 173. ISBN 0906670446.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ von Volborth, Carl-Alexander (1981). Heraldry: Customs, Rules and Styles. Poole: New Orchard Editions. pp. p 44-45. ISBN 185079037X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Dave's Mythical Creatures and Places:Ancient Egyptian Gods and Creatures. This appears to be the sole online depiction of a creature with this name.

- ^ One example is shown in a photograph among the resources for a Greek archeology course at the University at Albany. However, apart from the file name it's not clear that this is a "true" griffin: The body is more like a leopard's, the head like a hawk's or other bird's, and it has no wings.

- ^

Mayor, Adrienne (2000). The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691058636.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Giglioli, G. Q. (1935). L'Arte Etruria. Milan.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Bedingfeld, Henry (1993). Heraldry. Wigston: Magna Books. pp. p 80-81. ISBN 1854224336.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Carlos Parada, Greek Mythology Link, "Bestiary"

- ^ G.F. Hill, in Journal of the Hellenic Society (1923:160-61, noted in Fox 1973:506.

- ^ White, T. H. (1992 (1954)). The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation From a Latin Bestiary of the Twelfth Century. Stroud: Alan Sutton. pp. pp 22-24. ISBN 075090206X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Philadelphia Museum of Art - Giving : Giving to the Museum : Specialty License Plates

- ^ Philadelphia Museum of Art :: Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States :: Glass Steel and Stone

See also

- Eyrie, a girffin like Neopet

- Gallery of flags with animals#Griffin

- Griffin (surname)

- Griffon (Dungeons & Dragons)

- Hippogriff

- Homa

- JAS 39 Gripen, a fighter aircraft built by Saab

- SAAB Automobile Badge/Logo built by SAAB/General Motors Saab Automobile

- Simurgh

- Sphinx

External links

- The Gryphon Pages, a repository of griffin lore and information

Further reading

- Bisi, Anna Maria, Il grifone: Storia di un motivo iconografico nell'antico Oriente mediterraneo (Rome:Università) 1965.