Calligraphy: Difference between revisions

m Repairing 1 and tagging 2 external links using Checklinks; formatting: 6x heading-style, 6x nbsp-dash, 2x HTML entity, 2x unicode-escape, mdash, whitespace (using Advisor.js) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Redirect|Lettering|lettering in technical drawing|Technical lettering|lettering in comic books|letterer}} |

{{Redirect|Lettering|lettering in technical drawing|Technical lettering|lettering in comic books|letterer}} |

||

{{ |

{{copyedit|date=October 2013}} |

||

{{Calligraphy}} |

|||

'''Calligraphy''' (from {{lang-grc|[[:wikt:κάλλος|κάλλος]]}} ''kallos'' "beauty" and {{lang|grc|[[:wikt:γραφή|γραφή]]}} ''graphẽ'' "writing") is a [[Visual arts|visual art]] related to [[writing]]. It is the design and execution of lettering with a broad tip instrument or [[brush]] in one stroke (as opposed to built up lettering, in which the letters are drawn).<ref name=mediaville1996 />{{rp|17}} A contemporary definition of calligraphic practice is "the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious, and skillful manner".<ref name=mediaville1996 />{{rp|18}} |

|||

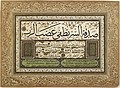

[[Image:Ijazah3.jpg|thumb|An [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]] [[ijazah]] written in [[Arabic language|Arabic]] certifying competence in calligraphy, 1206 [[Islamic calendar|AH]]/1791 [[AD]]]] |

|||

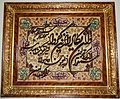

[[File:Van yakad.jpg|thumb|[[Quran]] verses on [[Pictorial carpet]]]] |

|||

Modern calligraphy ranges from functional inscriptions and designs to fine-art pieces where the letters may or may not or may not be legible.<ref name=mediaville1996 /> Classical calligraphy differs from [[typography]] and non-classical hand-lettering, though a calligrapher may practice both.<ref>{{de icon}} {{cite book|author=Pott, G.|year=2006|title=Kalligrafie: Intensiv Training|trans_title=Calligraphy: Intensive Training|publisher=Verlag Hermann Schmidt|isbn=9783874397001}}</ref><ref>{{de icon}} {{cite book|author=Pott, G.|year=2005|title=Kalligrafie: Erste Hilfe und Schrift-Training mit Muster-Alphabeten|publisher=Verlag Hermann Schmidt|isbn=9783874396752}}</ref><ref name=zapf2007>{{cite book|author=Zapf, H.|year=2007|title=Alphabet Stories: A Chronicle of technical developments|publisher=Cary Graphic Arts Press|location=Rochester, New York|isbn=9781933360225}}</ref><ref name=zapf2006>{{cite book|author=Zapf, H.|year=2006|title=The world of Alphabets: A kaleidoscope of drawings and letterforms}} CD-ROM</ref> |

|||

'''Calligraphy''' (from {{lang-grc|[[:wikt:κάλλος|κάλλος]]}} ''kallos'' "beauty" + {{lang|grc|[[:wikt:γραφή|γραφή]]}} ''graphẽ'' "writing") is a type of [[Visual arts|visual art]] related to [[writing]]. It is the design and execution of lettering with a broad tip instrument or brush in one stroke (as opposed to built up lettering, in which the letters are drawn.) (Mediavilla 1996: 17). A contemporary definition of calligraphic practice is "the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious and skillful manner" (Mediavilla 1996: 18). The story of writing is one of aesthetic evolution framed within the technical skills, transmission speed(s) and material limitations of a person, time and place (Diringer 1968: 441). A style of writing is described as a script, hand or alphabet (Fraser and Kwiatkowski 2006; Johnston 1909: Plate 6). |

|||

Calligraphy continues to flourish in the forms of [[wedding]] and event invitations, [[font]] design and typography, original hand-lettered [[logo]] design, [[religious art]], announcements, [[graphic design]] and commissioned calligraphic art, cut stone [[inscription]]s, and memorial [[document]]s. It is also used for [[Theatrical property|prop]]s and moving images for film and television, [[testimonial]]s, [[birth certificate|birth]] and [[death certificate|death]] certificates, [[map]]s, and other works involving writing.<ref>{{de icon}} {{cite book|author=Propfe, J.|year=2005|title=SchreibKunstRaume: Kalligraphie im Raum Verlag|publisher=George D.W. Callwey GmbH & Co.K.G.|location=Munich|isbn=9783766716309}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Geddes, A.|author3=Dion, C.|year=2004|title=Miracle: a celebration of new life|publisher=Photogenique Publishers|location=Auckland|isbn= 9780740746963}}</ref> Some of the finest works of modern calligraphy are [[Royal charter|charters]] and [[letters patent]] issued by [[monarch]]s and [[great officers of state|officers of state]] in various countries. |

|||

Modern calligraphy ranges from functional hand-lettered inscriptions and designs to fine-art pieces where the abstract expression of the handwritten mark may or may not compromise the legibility of the letters (Mediavilla 1996). Classical calligraphy differs from [[typography]] and non-classical hand-lettering, though a calligrapher may create all of these; characters are historically disciplined yet fluid and spontaneous, at the moment of writing (Pott 2006 and 2005; Zapf 2007 and 2006). |

|||

== Western == |

|||

Calligraphy continues to flourish in the forms of [[wedding]] and event invitations, [[font]] design/[[typography]], original hand-lettered [[logo]] design, [[religious art]], announcements/[[graphic design]]/commissioned calligraphic art, cut stone [[inscription]]s and memorial [[document]]s. It is also used for [[Theatrical property|prop]]s and moving images for film and television, [[testimonial]]s, [[birth certificate|birth]] and [[death certificate|death]] certificates, [[map]]s, and other works involving writing (see for example Letter Arts Review; Propfe 2005; Geddes and Dion 2004). Some of the finest works of modern calligraphy are [[Royal charter|charters]] and [[letters patent]] issued by [[monarch]]s and [[great officers of state|officers of state]] in various countries. |

|||

== Western calligraphy == |

|||

{{Main|Western calligraphy}} |

{{Main|Western calligraphy}} |

||

{{see also|Latin alphabet}} |

|||

[[Image:Westerncalligraphy.jpg|thumb|left|Modern Western calligraphy]] |

|||

[[Image:Westerncalligraphy.jpg|thumb|left|Modern Western calligraphy]] |

|||

=== Tools and techniques === |

|||

=== Tools === |

|||

[[File:Pointed pen parts.svg|thumb|A calligraphic pen head, with parts names.]] |

[[File:Pointed pen parts.svg|thumb|A calligraphic pen head, with parts names.]] |

||

The principal tools for a calligrapher are the [[pen]], which may be flat-balled or round-nibbed, and the [[ |

The principal tools for a calligrapher are the [[pen]], which may be flat-balled or round-[[nib|nibbed]], and the [[paintbrush|brush]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Reaves, M.|author2=Schulte, E.|year=2006|title=Brush Lettering: An instructional manual in Western brush calligraphy|edition=Revised|publisher=Design Books|location=New York}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|editor-last=Child|editor-first=H.|year=1985|title=The Calligrapher's Handbook|publisher=Taplinger Publishing Co.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|editor-last=Lamb|editor-first=C.M.|origyear=1956|title=Calligrapher's Handbook|publisher=Pentalic|year=1976}}</ref> Pens may vary from the For some decorative purposes, multi-nibbed pens—steel brushes—can be used. However, works have also been made with [[felt-tip pen|felt-tip]] and [[ballpoint pen]]s, although these works do not employ angled lines. |

||

[[Ink]] for writing is usually water-based and much less viscous than the oil-based inks used in printing. High quality paper, which has good consistency of porosity,{{clarify|date=October 2013}} will enable cleaner lines,{{Citation needed|date=February 2007}} although [[parchment]] or [[vellum]] is often used, as a knife can be used to erase work and a [[light box]] is not needed to allow lines to pass through it. Normally, light boxes and templates are used to achieve straight lines without pencil markings detracting from the work. Ruled paper, either for a light box or direct use, is most often ruled every quarter or half inch, although inch spaces are occasionally used, such as with ''litterea unciales'' (hence the name), and college-[[ruled paper]] often acts as a guideline well.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://calligraphyislamic.com |title=Calligraphy Islamic website |publisher=Calligraphyislamic.com |date= |accessdate=2012-06-18}}</ref> |

|||

Pens may be obtained from various stationery sources — from the traditional "nib" pens dipped in ink, to calligraphy pens that have cartridges built-in, avoiding the need to have to continually dip them into inkwells. |

|||

=== Style === |

|||

;Styles & techniques |

|||

Sacred Western calligraphy has some special features, such as the illumination of the first letter of each book or chapter in medieval times. A decorative "carpet page" may precede the literature, filled with ornate, geometrical depictions of bold-hued animals. The [[Lindisfarne Gospels]] ( |

Sacred [[Western calligraphy]] has some special features, such as the illumination of the first letter of each book or chapter in medieval times. A decorative "carpet page" may precede the literature, filled with ornate, geometrical depictions of bold-hued animals. The [[Lindisfarne Gospels]] (715–720 AD) are an early example.<ref>{{cite book|author=Brown, M.P.|year=2004|title=Painted Labyrinth: The World of the Lindisfarne Gospel|edition=Revised Ed|publisher=British Library}}</ref> |

||

As with Chinese or |

As with [[Chinese calligraphy|Chinese]] or [[Arabic calligraphy]], Western calligraphic script had strict rules and shapes. Quality writing had a rhythm and regularity to the letters, with a "geometrical" order of the lines on the page. Each character had, and often still has, a precise [[stroke order]]. |

||

Unlike a typeface, irregularity in the characters' size, style and colors |

Unlike a typeface, irregularity in the characters' size, style, and colors increases aesthetic value, though the content may be illegible. Many of the themes and variations of today's contemporary Western calligraphy are found in the pages of [[The Saint John's Bible]]. A particularly modern example is [[Timothy Botts]]' illustrated edition of the Bible, with 360 calligraphic images as well as a calligraphy [[typeface]].<ref>{{cite book|title=The Bible: New Living Translation|publisher=Tyndale House Publishers|year=2000}}</ref> |

||

=== |

=== History === |

||

[[Image:Calligraphy.malmesbury.bible.arp.jpg|thumb|Calligraphy in a [[Latin]] [[Bible]] of |

[[Image:Calligraphy.malmesbury.bible.arp.jpg|thumb|Calligraphy in a [[Latin]] [[Bible]] of 1407 on display in [[Malmesbury Abbey]], [[Wiltshire]], England. This bible was hand written in Belgium, by Gerard Brils, for reading aloud in a [[monastery]].]] |

||

[[File:მარიამისეული ქართლის ცხოვრება.JPG|thumb|The [[Georgian calligraphy]] is centuries-old tradition of an artistic writing of the [[Georgian language]] with its [[Georgian alphabet|three alphabets]].]] |

|||

Western calligraphy is recognizable by the use of the [[Latin script]]. The [[Latin alphabet]] appeared about 600 BC, in Rome, and by the first century{{Clarify|date=January 2011}} developed into [[Roman imperial capitals]] carved on stones, [[Rustic capitals]] painted on walls, and [[Roman cursive]] for daily use. In the second and third centuries the [[uncial]] lettering style developed. As writing withdrew to monasteries, uncial script was found more suitable for copying the Bible and other religious texts. It was the monasteries which preserved calligraphic traditions during the fourth and fifth centuries, when the Roman Empire fell and Europe entered the Dark Ages.<ref> |

Western calligraphy is recognizable by the use of the [[Latin script]]. The [[Latin alphabet]] appeared about 600 BC, in Rome, and by the first century{{Clarify|date=January 2011}} developed into [[Roman imperial capitals]] carved on stones, [[Rustic capitals]] painted on walls, and [[Roman cursive]] for daily use. In the second and third centuries the [[uncial]] lettering style developed. As writing withdrew to monasteries, uncial script was found more suitable for copying the Bible and other religious texts. It was the monasteries which preserved calligraphic traditions during the fourth and fifth centuries, when the Roman Empire fell and Europe entered the [[Dark Ages]].<ref>{{fr icon}} {{cite book|author=Sabard, V.|author2=Geneslay, V.|author3=Rébéna, L.|title=Calligraphie latine: Initiation|location=Fleurus, Paris|edition=7th|year=2004|pages=8–11|isbn=978-2215021308|trans_title=Latin calligraphy: Introduction}}</ref> |

||

At the height of the Roman Empire its power reached as far as Great Britain; when the empire fell, its literary influence remained. The [[Semi-uncial]] generated the Irish Semi-uncial, the small Anglo-Saxon. Each region |

At the height of the Roman Empire, its power reached as far as Great Britain; when the empire fell, its literary influence remained. The [[Semi-uncial]] generated the Irish Semi-uncial, the small Anglo-Saxon. Each region developed its own standards following the main monastery of the region (i.e. [[Merovingian script]], Laon script, [[Luxeuil Abbey|Luxeuil script]], [[Visigothic script]], [[Beneventan script]]), which are mostly cursive and hardly readable. |

||

The rising [[Carolingian|Carolingian Dynasty]] Empire encouraged a new standardized script, which was developed by several famous monasteries (including [[Corbie Abbey]] and [[Beauvais]]) around the eighth century. The script from [[Saint |

The rising [[Carolingian|Carolingian Dynasty]] Empire encouraged a new standardized script, which was developed by several famous monasteries (including [[Corbie Abbey]] and [[Beauvais]]) around the eighth century. The script from [[Martin of Tours|Saint Martin of Tours]] was ultimately set as the Imperial standard, named the [[Carolingian script]] (or "the Caroline"). From the powerful Carolingian Empire, this standard also became used in neighboring kingdoms. |

||

In the eleventh century, the Caroline evolved into the [[blackletter|Gothic script]], which was more compact and made it possible to fit more text on a page.<ref> |

In the eleventh century, the Caroline evolved into the [[blackletter|Gothic script]], which was more compact and made it possible to fit more text on a page.<ref name=lovett2000>{{cite book|author=Lovett, Patricia|title=Calligraphy and Illumination: A History and Practical Guide|publisher=Harry N. Abrams|year=2000|isbn= 978-0810941199}}</ref>{{rp|72}} The Gothic calligraphy styles became dominant throughout Europe; and in 1454, when [[Johannes Gutenberg]] developed the first printing press in Mainz, Germany, he adopted the Gothic style, making it the first [[typeface]].<ref name=lovett2000 />{{rp|141}} |

||

In the 15th century, the rediscovery of old Carolingian texts encouraged the creation of the [[humanist minuscule]] or ''littera antiqua''. |

In the 15th century, the rediscovery of old Carolingian texts encouraged the creation of the [[humanist minuscule]] or ''littera antiqua''. The 17th century saw the [[Bastarda|Batarde script]] from France, and the 18th century saw the [[English script (calligraphy)|English script]] spread across Europe and world through their books. |

||

Contemporary typefaces used by computers, from word processors like [[Microsoft Word]] or [[Apple Pages]] to professional designers' software like [[Adobe InDesign]], owe a considerable debt to the past and to a small number of professional typeface designers today.<ref name=mediaville1996>{{cite book|last=Mediaville|first=Claude|title=Calligraphy: From Calligraphy to Abstract Painting|year=1996|publisher=Scirpus-Publications|location=Belgium|isbn=9080332518}}</ref><ref name=zapf2007 /><ref>{{cite book|author=Henning, W.E.|year=2002|title=An Elegant Hand: The Golden Age of American Penmanship and Calligraphy|editor-last=Melzer|editor-first=P.|publisher=Oak Knoll Press|location=New Castle, Delaware|isbn=978-1584560678}}</ref> |

|||

=== Influences === |

=== Influences === |

||

Several other Western styles use the same tools and practices, but differ by |

Several other Western styles use the same tools and practices, but differ by character set and stylistic preferences. |

||

For [[Slavonic lettering]], the history of the [[Slavic peoples|Slavonic]] and consequently [[Russia]]n [[writing system]]s differs fundamentally from the one of the [[Latin|Latin language]]. It evolved from the 10th century to today. |

For [[Slavonic lettering]], the history of the [[Slavic peoples|Slavonic]] and consequently [[Russia]]n [[writing system]]s differs fundamentally from the one of the [[Latin|Latin language]]. It evolved from the 10th century to today. |

||

{{anchor|East Asian calligraphy}} |

{{anchor|East Asian calligraphy}} |

||

== |

== East Asian == |

||

{{ |

{{See also|Chinese calligraphy|Japanese calligraphy|Korean calligraphy}} |

||

{{see also|Chinese characters}} |

|||

[[File:Mi Fu-On Calligraphy.jpg|thumb|''On Calligraphy'' by [[Mi Fu]], [[Song Dynasty]]]] |

[[File:Mi Fu-On Calligraphy.jpg|thumb|''On Calligraphy'' by [[Mi Fu]], [[Song Dynasty]]]] |

||

The Chinese name for calligraphy is ''{{transl|zh|shūfǎ}}'' ({{lang|zh-tw|書法}} in [[Taiwanese Chinese|Taiwanese]], literally "the method or law of writing");<ref>{{lang|zh-tw|書}} (Taiwanese) being here used as in {{lang|zh-cn|楷书}} (Cantonese) or {{lang|zh-tw|楷書}} (Taiwanese), meaning "writing style".{{clarify|date=October 2013}}</ref> the Japanese name ''{{transl|ja|shodō}}'' ({{lang|ja|書道}}, literally "the way or principle of writing"); the Korean is ''{{transl|ko|seoye}}'' ({{lang-ko|서예|書藝}}, literally "the art of writing"); and the Vietnamese is {{lang|vt|Thư pháp}} ({{script|Hani|書法}}, literally "the way of letters or words"). The calligraphy of [[CJK characters|East Asian characters]] is an important and appreciated aspect of [[East Asian cultural sphere|East Asian culture]]. |

|||

=== Names, tools and techniques === |

|||

;Names |

|||

The local name for calligraphy is ''Shūfǎ'' {{lang|zh-tw|書法}} in China, literally "The way/method/law of writing";<ref>{{lang|zh-tw|書}} being here used as in {{lang|zh-cn|楷书}}/{{lang|zh-tw|楷書}}, meaning "writing style".</ref> ''Shodō'' {{lang|ja|書道}} in Japan, literally "The way/principle of writing"; ''Seoye'' (서예) 書藝 in Korea, literally "The art of writing"; and Thư pháp 書法 in Vietnam, literally "The way of letters/words". The calligraphy of [[CJK characters|East Asian characters]] is an important and appreciated aspect of [[East Asian cultural sphere|East Asian culture]]. |

|||

===Technique=== |

|||

;Tools: |

|||

Traditional [[East Asia]]n writing uses the [[Four Treasures of the Study]] ( |

Traditional [[East Asia]]n writing uses the [[Four Treasures of the Study]] ({{lang|zh-tw|文房四寶}} in Taiwanese and {{lang|zh-cn|文房四宝}} in Cantonese): the [[ink brush]]es to write [[Chinese character]]s, Chinese ink, paper, and inkstone, known as the ''Four Friends of the Study'' ({{lang-ko|문방사우|文房四友}}) in Korea. In addition to these four tools, desk pads and paperweights are also used. |

||

The shape, size, stretch, and [[Brush#Bristles|hair type]] of the ink brush, the color, color density and water density of the ink, as well as the paper's water absorption speed and surface texture are the main physical parameters influencing the final result. The calligrapher also influences the result by the quantity of ink and water he lets the brush take, then by the pressure, inclination, and direction he gives to the brush, producing thinner or bolder strokes, and smooth or toothed borders. Eventually, the speed, accelerations, decelerations of the writer's moves, turns, and crochets, and the [[stroke order]] give the "spirit" to the characters, by influencing greatly their final shapes. |

|||

;Technique |

|||

The shape, size, stretch and hair type of the ink brush, the color, color density and water density of the ink, as well as the paper's water absorption speed and surface texture are the main physical parameters influencing the final result. The calligrapher also influences the result by the quantity of ink/water he lets the brush take, then by the pressure, inclination, and direction he gives to the brush, producing thinner or bolder strokes, and smooth or toothed borders. Eventually, the speed, accelerations, decelerations of the writer's moves, turns, and crochets, and the [[stroke order]] give the "spirit" to the characters, by influencing greatly their final shapes. |

|||

=== |

=== History === |

||

[[File:Van Mieu han tu 5412916981 273dedbe99.jpg|thumb|A Vietnamese calligraphist writing in ''[[Hán-Nôm]]'' in preparation for [[Tết]], at the [[Temple of Literature, Hanoi]] (2011)]] |

[[File:Van Mieu han tu 5412916981 273dedbe99.jpg|thumb|A Vietnamese calligraphist writing in ''[[Hán-Nôm]]'' in preparation for [[Tết]], at the [[Temple of Literature, Hanoi]] (2011)]] |

||

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

NOTICE 1: This section is a copy of from article [[East Asian calligraphy]], section #Evolution and Styles. If you want add content or |

NOTICE 1: This section is a copy of from article [[East Asian calligraphy]], section #Evolution and Styles. If you want add content or sources, add it there as well. |

||

NOTICE 2: Try not to make super-short sections. --> |

|||

NOTICE 2: really short sections (less than 5 lines) are to avoid. Since "Ancient China" have 5, "Imperial China" . and "Cursive styles and hand-written styles" 2 lines : don't make editable sections for each of this too small issue. --> |

|||

====China==== |

|||

In [[Ancient China|ancient China]], the oldest Chinese characters existing are [[Oracle bone script|Jiǎgǔwén characters]] carved on |

In [[Ancient China|ancient China]], the oldest Chinese characters existing are [[Oracle bone script|Jiǎgǔwén characters]] carved on ox [[scapula]]e and tortoise [[plastrons]], because the dominators in [[Shang Dynasty]] carved pits on such animalss' bones and |

||

then baked them to gain auspice of military affairs, agricultural harvest,or even procreating and weather |

then baked them to gain auspice of military affairs, agricultural harvest, or even procreating and weather. During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made, the characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved.(Keightley, 1978). With the development of ''[[Bronzeware script|Jīnwén]]'' (Bronzeware script) and ''[[Large Seal Script|Dàzhuàn]]'' (Large Seal Script) "cursive" signs continued. Moreover, each archaic kingdom of current China had its own set of characters. |

||

;Imperial China |

|||

In [[Imperial era of Chinese history|Imperial China]], the graphs on old steles — some dating from 200 BC, and in Xiaozhuan style — are still accessible. |

In [[Imperial era of Chinese history|Imperial China]], the graphs on old steles — some dating from 200 BC, and in Xiaozhuan style — are still accessible. |

||

About 220 BC, the emperor [[Qin Shi Huang]], the first to conquer the entire Chinese basin, imposed several reforms, among them [[Li Si]]'s character unification, which created a set of 3300 standardized ''Xiǎozhuàn'' characters.<ref>{{cite book|last= Fazzioli |first= Edoardo |others= |

About 220 BC, the emperor [[Qin Shi Huang]], the first to conquer the entire Chinese basin, imposed several reforms, among them [[Li Si]]'s character unification, which created a set of 3300 standardized ''{{transl|zh|Xiǎozhuàn}}'' characters.<ref>{{cite book|last= Fazzioli |first= Edoardo |others= Calligraphy by Rebecca Hon Ko |title= Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History Of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters |publisher= [[Abbeville Publishing Group (Abbeville Press, Inc.)|Abbeville Press]] |location= New York |isbn= 0896597741 |page= 13 |quote=And so the first Chinese dictionary was born, the ''Sān Chāng'', containing {{formatnum:3300}} characters|year= 1987 }}</ref> Despite the fact that the main writing implement of the time was already the brush, few papers survive from this period, and the main examples of this style are on steles. |

||

The [[Clerical script|Lìshū style]] (clerical script) which is more regularized, and in some ways similar to modern text, have been also authorised under Qin Shi Huangdi.<ref name="Blakney, p6"> |

The [[Clerical script|Lìshū style]] (clerical script) which is more regularized, and in some ways similar to modern text, have been also authorised under Qin Shi Huangdi.<ref name="Blakney, p6">{{cite book|author=R. B. Blakney|title=A Course in the Analysis of Chinese Characters|page=148|publisher=Lulu.com|year=2007|isbn=978-1-897367-11-7|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=7-ZYX4xCXygC&lpg=PA3&ots=YxoWBtBfN-&dq=%22Li%20Ssu%22%20reform%20small%20seal&lr=&pg=PA6#v=onepage&q=Li%20Ssu&f=false|page=6}}</ref> |

||

{{cite book|author=R. B. Blakney|title=A Course in the Analysis of Chinese Characters|page=148|publisher=Lulu.com|year=2007|isbn=978-1-897367-11-7}}</ref> |

|||

[[Regular script|Kǎishū style]] (traditional regular script) — still in use today — and attributed to [[Wang Xizhi]] (王羲之, |

[[Regular script|Kǎishū style]] (traditional regular script) — still in use today — and attributed to [[Wang Xizhi]] ({{lang|zh|王羲之}}, 303–361) and his followers, is even more regularized.<ref name="Blakney, p6" /> Its spread was encouraged by [[Li Siyuan|Emperor Mingzong of Later Tang]] (926–933), who ordered the printing of the classics using new wooden blocks in Kaishu. Printing technologies here allowed a shape stabilization. The Kaishu shape of characters 1000 years ago was mostly similar to that at the end of Imperial China.<ref name="Blakney, p6" /> But small changes have be made, for example in the shape of <big>{{lang|zh|广}}</big> which is not absolutely the same in the [[Kangxi Dictionary]] of 1716 as in modern books. The Kangxi and current shapes have tiny differences, while stroke order is still the same, according to old style.<ref>{{zh icon}} {{cite book|title=康熙字典|trans_title=Kangxi Zidian|year=1716|url=http://ctext.org/library.pl?if=en&res=77358|page=41}}. See, for example, the radicals <big>{{lang|zh|卩}}</big>, <big>{{lang|zh|厂}}</big>, or <big>{{lang|zh|广}}</big>. The 2007 common shape for those characters does not clearly show the stroke order, but old versions, visible on p.41, clearly allow the stroke order to be determined.</ref> |

||

Styles which did not survive include Bāfēnshū, a mix made of Xiaozhuan style at 80%, and Lishu at 20%.<ref name="Blakney, p6" /> |

Styles which did not survive include Bāfēnshū, a mix made of Xiaozhuan style at 80%, and Lishu at 20%.<ref name="Blakney, p6" /> |

||

Some [[ |

Some [[variant Chinese character]]s were unorthodox or locally used for centuries. They were generally understood but always rejected in official texts. Some of these unorthodox variants, in addition to some newly created characters, compose the [[Simplified Chinese]] character set. |

||

=====Styles===== |

|||

;Cursive styles and hand-written styles |

|||

Cursive styles such as ''[[Semi-cursive script| |

Cursive styles such as ''[[Semi-cursive script|{{transl|zh|xíngshū}}]]'' (semi-cursive or running script) and ''[[Grass script|{{transl|zh|cǎoshū}}]]'' (cursive or grass script) are less constrained and faster, where more movements made by the writing implement are visible. These styles' stroke orders vary more, sometimes creating radically different forms. They are descended from Clerical script, in the same time as Regular script ([[Han Dynasty]]), but ''{{transl|zh|xíngshū}}'' and ''{{transl|zh|cǎoshū}}'' were used for personal notes only, and never used as a standard. The ''{{transl|zh|cǎoshū}}'' style was highly appreciated in [[Emperor Wu of Han]] reign (140–187 AD).<ref name="Blakney, p6" /> |

||

;Printed and computer styles |

|||

Examples of modern printed styles are [[Ming (typeface)|Song]] from the [[Song Dynasty]]'s [[Four Great Inventions of ancient China#Printing|printing press]], and [[East Asian sans-serif typeface|sans-serif]]. These are not considered traditional styles, and are normally not written. |

Examples of modern printed styles are [[Ming (typeface)|Song]] from the [[Song Dynasty]]'s [[Four Great Inventions of ancient China#Printing|printing press]], and [[East Asian sans-serif typeface|sans-serif]]. These are not considered traditional styles, and are normally not written. |

||

{{-}} |

{{-}} |

||

=== Influences === |

=== Influences === |

||

{{refimprove|section|date=October 2013}} |

|||

[[File:Oura Kanetake peace 1910.jpg|thumb|[[Japanese calligraphy]], the word "peace" and the signature of the [[Meiji period]] calligrapher [[Ōura Kanetake]], 1910 ]] |

[[File:Oura Kanetake peace 1910.jpg|thumb|[[Japanese calligraphy]], the word "peace" and the signature of the [[Meiji period]] calligrapher [[Ōura Kanetake]], 1910 ]] |

||

Japanese and Korean people developed specific sensibilities and styles of calligraphy. For example, [[Japanese calligraphy]] go out of the set of [[CJK strokes]] to also include local alphabets such as [[hiragana]] and [[katakana]], with specific problematics such as new curves and moves, and specific materials ([[Japanese paper]], ''{{transl|ja|washi}}'' {{lang|ja|和紙}}, and Japanese ink).<ref>{{cite book|last=Suzuki|first=Yuuko|title=An introduction to Japanese calligraphy|year=2005|publisher=Search|location=Tunbridge Wells|isbn=978-1844480579}}</ref> In the case of [[Korean calligraphy]], the [[Hangeul]] and the existence of the circle required the creation of a new technique which usually confuses Chinese calligraphers. |

|||

;Other calligraphies |

|||

Japanese and Korean people developed specific sensibilities and styles of calligraphies. By example, [[Japanese calligraphy]] go out of the set of [[CJK strokes]] to also include local alphabets such as [[hiragana]] and [[katakana]], with specific problematics such as new curves and moves, and specific materials (Japanese paper, "washi" 和紙, and Japanese ink).<ref>Yuuko Suzuki, Japanese calligraphy, Search Press, 2005, Calligraphie japonaise, éd.Fleurus, 2003, Paris</ref> In the case of [[Korean calligraphy]], the [[Hangeul]] and the existence of the circle required the creation of a new technique which usually confuses Chinese calligraphers. |

|||

Temporary calligraphy is a practice of water-only calligraphy on the floor, which dries out within minutes. This practice is especially appreciated by the new generation of retired Chinese in public parks of China. These will often open studio-shops in tourist towns offering traditional Chinese calligraphy to tourists. Other than writing the clients name, they also sell fine brushes as souvenirs and lime stone carved stamps. |

|||

Since late 1980's a few Chinese artists have branched out traditional [[Chinese calligraphy]] to a new territory by mingling [[Chinese characters]] with English letters; notable new forms of calligraphies are Xu Bin's [[Square Calligraphy]] and DanNie's [[Coolligraphy or Cooligrapgy]]. |

|||

Since late 1980's a few Chinese artists have branched out traditional Chinese calligraphy to a new territory by mingling [[Chinese characters]] with English letters; notable new forms of calligraphy are [[Xu Bing]]'s square calligraphy and DanNie's coolligraphy or cooligrapgy. |

|||

;Mongolian |

|||

[[Mongolian calligraphy]] is also influenced by Chinese calligraphy, from tools to style. |

[[Mongolian calligraphy]] is also influenced by Chinese calligraphy, from tools to style. |

||

Calligraphy has influenced [[ink and wash painting]], which is accomplished using similar tools and techniques. Calligraphy has influenced most major art styles in [[East Asia]], including [[ink and wash painting]], a style of [[Chinese painting|Chinese]], [[Korean painting|Korean]], [[Culture of Taiwan|Taiwanese]], [[Japanese painting]], and Vietnamese painting based entirely on calligraphy. |

|||

;Other arts |

|||

Calligraphy has influenced [[ink and wash painting]], which is accomplished using similar tools and techniques. Calligraphy has influenced most major art styles in [[East Asia]], including [[Ink and wash painting]], a style of [[Chinese painting|Chinese]], [[Korean painting|Korean]], [[Culture of Taiwan|Taiwanese]], [[Japanese painting]], and [[Vietnamese painting]] based entirely on calligraphy. |

|||

== South Asian |

== South Asian == |

||

{{refimprove|date=October 2013}} |

|||

{{see also|Brāhmī script}} |

|||

=== Indian |

=== Indian === |

||

{{Main|Indian calligraphy}} |

{{Main|Indian calligraphy}} |

||

{{too many quotes|section|date=October 2013}} |

|||

[[Image:Kurukshetra.jpg|thumb|left|An illustrated manuscript of the [[Mahabharata]] with calligraphy]] |

|||

On the subject of Indian calligraphy, {{ |

On the subject of Indian calligraphy, writes:<ref>{{Cite journal| last= Anderson | first=D. M. | year=2008 | title=Indic calligraphy | publisher=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]] 2008 }}.</ref> |

||

[[File:Odia calligraphy esabada Odia magazine eodissa.jpg|thumb|A Calligraphic design in [[Oriya script]]]] |

[[File:Odia calligraphy esabada Odia magazine eodissa.jpg|thumb|A Calligraphic design in [[Oriya script]]]] |

||

<blockquote> |

<blockquote> |

||

| Line 122: | Line 110: | ||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

<blockquote> |

<blockquote> |

||

In many parts of ancient India, the inscriptions were carried out in smoke-treated palm leaves. This tradition dates back to over two thousand years.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=10660&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html |title=Memory of the World | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |publisher= |

In many parts of ancient India, the inscriptions were carried out in smoke-treated palm leaves. This tradition dates back to over two thousand years.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=10660&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html |title=Memory of the World | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |publisher=UNESCO |date= |accessdate=2012-06-18}}</ref> Even after the Indian languages were put on paper in the 13th century, palm leaves where considered a preferred medium of writing owing to its longevity (nearly 400 years) compared to paper. Both sides of the leaves were used for writing. Long rectangular strips were gathered on top of one another, holes were drilled through all the leaves, and the book was held together by string. Books of this manufacture were common to [[Southeast Asia]]. The palm leaf was an excellent surface for penwriting, making possible the delicate lettering used in many of the scripts of southern Asia. |

||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

<blockquote> |

<blockquote> |

||

Burnt clay and [[ |

Burnt clay and [[copper]] were a favoured material for Indic inscriptions.{{Citation needed|date=April 2010}} In the north of India, birch bark was used as a writing surface as early as the 2nd century AD.{{Citation needed|date=April 2010}}. |

||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

=== Nepalese |

=== Nepalese === |

||

{{Main|Nepalese calligraphy}} |

|||

<!-- deleted file removed [[File:Jwajalapa.svg|right|thumb| ]]--> |

|||

[[Ranjana script]] is the primary form of Nepalese calligraphy. The script itself, along with its derivatives (like [[Lanydza Script|Lantsa]], [[Phagpa]], [[Kutila]]) are used in [[Nepal]], [[Tibet]], [[Bhutan]], [[Leh]], [[Mongolia]], coastal China, Japan, and Korea to write "[[Om mani padme hum]]" and other sacred [[Buddhist texts]], mainly those derived from [[Sanskrit]] and [[Pali]]. |

|||

=== Tibetan calligraphy === |

=== Tibetan calligraphy === |

||

| Line 139: | Line 127: | ||

Calligraphy is central in [[Tibet]]an culture. The script is derived from [[Indic script]]s. The nobles of Tibet, such as the High [[Lama]]s and inhabitants of the [[Potala Palace]], were usually capable calligraphers. [[Tibet]] has been a center of [[Buddhism]] for several centuries, and that religion places a great deal of significance on written word. This does not provide for a large body of [[secular]] pieces, although they do exist (but are usually related in some way to Tibetan Buddhism). Almost all high religious writing involved calligraphy, including letters sent by the [[Dalai Lama]] and other religious and secular authority. Calligraphy is particularly evident on their [[prayer wheels]], although this calligraphy was forged rather than scribed, much like Arab and Roman calligraphy is often found on buildings. Although originally done with a reed, Tibetan calligraphers now use chisel tipped pens and markers as well. |

Calligraphy is central in [[Tibet]]an culture. The script is derived from [[Indic script]]s. The nobles of Tibet, such as the High [[Lama]]s and inhabitants of the [[Potala Palace]], were usually capable calligraphers. [[Tibet]] has been a center of [[Buddhism]] for several centuries, and that religion places a great deal of significance on written word. This does not provide for a large body of [[secular]] pieces, although they do exist (but are usually related in some way to Tibetan Buddhism). Almost all high religious writing involved calligraphy, including letters sent by the [[Dalai Lama]] and other religious and secular authority. Calligraphy is particularly evident on their [[prayer wheels]], although this calligraphy was forged rather than scribed, much like Arab and Roman calligraphy is often found on buildings. Although originally done with a reed, Tibetan calligraphers now use chisel tipped pens and markers as well. |

||

== Islamic |

== Islamic == |

||

{{Main|Islamic calligraphy}} |

{{Main|Islamic calligraphy}} |

||

{{see also|Arabic alphabet}} |

|||

[[Image:AndalusQuran.JPG|thumb|left|A page of a 12th-century [[Qur'an]] written in the [[al-Andalus]] script]] |

|||

=== Islamic calligraphy === |

|||

Islamic calligraphy (''calligraphy'' in Arabic is ''{{transl|ar|khatt ul-yad}}'' {{rtl-lang|ar|خط اليد}}) has evolved alongside Islam]] and the [[Arabic language. As it is based on Arabic letters, some call it "Arabic calligraphy". However the term "Islamic calligraphy" is a more appropriate term as it comprises all works of calligraphy by the Muslim calligraphers from [[Andalusia]] in modern [[Spain]] to China. |

|||

[[Image:AndalusQuran.JPG|thumb|left|A page of a 12th-century [[Qur'an]] written in the [[al-Andalus|Andalusi]] script]] |

|||

<!-- deleted file removed [[Image:Learning Islamic calligraphy.jpg|thumb|The instruments and work of a student calligrapher]] --> |

|||

Islamic calligraphy (''calligraphy'' in Arabic is ''Khatt ul-Yad'' خط اليد) has evolved alongside the [[religion]] of [[Islam]] and the [[Arabic language]]. As it is based on Arabic letters, some call it "Arabic calligraphy". However the term "Islamic calligraphy" is a more appropriate term as it comprises all works of calligraphy by the Muslim calligraphers from [[Andalusia]] in modern [[Spain]] to China. |

|||

Islamic calligraphy is associated with geometric Islamic art ([[Arabesque (Islamic art)|arabesque]]) on the walls and ceilings of [[mosque]]s as well as on the page. Contemporary artists in the [[Islamic world]] draw on the heritage of calligraphy to use calligraphic inscriptions or abstractions. |

|||

Islamic calligraphy excelled due to the forms of Arabic letters, composed of dots, lines and curves. These attributes give the artist a freedom to create. The script is functional as well as artistic and graphic, therefore even those who do not understand the writing can enjoy the sight of it. |

|||

Instead of recalling something related to the spoken word, calligraphy for [[Muslim]]s is a visible expression of the highest art of all, the art of the [[spirituality|spiritual]] world. Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The [[Qur'an]] has played an important role in the development and evolution of the Arabic language, and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. Proverbs and passages from the Qur'an are still sources for Islamic calligraphy. |

|||

Islamic calligraphy is associated with geometric [[Islamic]] art ([[Arabesque (Islamic art)|arabesque]]) on the walls and ceilings of [[mosque]]s as well as on the page. Contemporary [[artists]] in the [[Islamic world]] draw on the heritage of calligraphy to use calligraphic inscriptions or abstractions. |

|||

It is generally accepted that Islamic calligraphy excelled during the [[Ottoman era]]. Turkish calligraphers still present the most refined and creative works. Istanbul is an open exhibition hall for all kinds and varieties of calligraphy, from inscriptions in mosques to fountains, schools, houses, etc. {{-}} |

|||

Instead of recalling something related to the spoken word, calligraphy for [[Muslim]]s is a visible expression of the highest art of all, the art of the [[spirituality|spiritual]] world. Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The [[holy book]] of Islam, al-[[Qur'an]], has played an important role in the development and evolution of the Arabic language, and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. [[Proverb]]s and passages from the Qur'an are still sources for Islamic calligraphy. |

|||

=== Persian === |

|||

It is generally accepted that Islamic calligraphy excelled during the Ottoman era. Turkish calligraphers still present the most refined and creative works. Istanbul is an open exhibition hall for all kinds and varieties of calligraphy, from inscriptions in mosques to fountains, schools, houses, etc. {{-}} |

|||

=== Persian calligraphy === |

|||

{{Main|Persian calligraphy}} |

{{Main|Persian calligraphy}} |

||

[[Image:Nastaliq-proportions.jpg|thumb|Example showing Nastaliq's proportional rules]] |

[[Image:Nastaliq-proportions.jpg|thumb|Example showing Nastaliq's proportional rules]] |

||

[[Image:Chayyam guyand kasan behescht ba hur chosch ast small.png|thumb|[[Shikasta Nastaʿlīq]]]] |

|||

The history of calligraphy in [[Persia]] dates back to the pre-Islam era. In [[Zoroastrianism]] beautiful and clear writings were always praised. |

|||

It is believed that ancient Persian script was invented by about 600–500 BC to provide monument inscriptions for the [[Achaemenid_Empire#Achaemenid_kings_and_rulers|Achaemenid kings]]. These scripts consisted of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal nail-shape letters, which is why it is called [[Cuneiform script|"script of nails/cuneiform script"]] (''{{transl|fa|khat-e-mikhi}}) in [[Persian language|Persian]]. Centuries later, other scripts such as "[[Pahlavi scripts|Pahlavi]]" and "[[Avestan script|Avestan]]" scripts were used in ancient Persia. |

|||

;History and evolution |

|||

It is believed that ancient Persian script was invented by about 600-500 BC to provide monument inscriptions for the Achaemenid kings. These scripts consisted of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal nail-shape letters and that is the reason in [[Persian language|Persian]] it is called [[Cuneiform script|"Script of Nails/Cuneiform Script"]] (Khat-e-Mikhi). Centuries later, other scripts such as "[[Pahlavi scripts|Pahlavi]]" and "[[Avestan script|Avestan]]" scripts were used in ancient Persia. |

|||

After the Arab conquest in the 7th century, Persians adapted the Arabic alphabet to fit the Persian language |

After the Arab conquest in the 7th century, Persians adapted the Arabic alphabet to fit the Persian language, which developed into the modern Persian alphabet. The Arabic alphabet has 28 characters, to which Iranians added another four letters to account for sounds and letters in Persian that do not exist in Arabic. |

||

====Contemporary scripts==== |

|||

''{{transl|fa|Nasta'liq}}'' is the most popular contemporary style among classical Persian calligraphy scripts; Persian calligraphers call it the "bride of calligraphy scripts". This calligraphy style has been based on such a strong structure that it has changed very little since. [[Mir Ali Tabrizi]] had found the optimum composition of the letters and graphical rules so it has just been fine-tuned during the past seven centuries. It has very strict rules for graphical shape of the letters and for combination of the letters, words, and composition of the whole calligraphy piece. |

|||

== Mayan |

== Mayan == |

||

[[Image:Dresden codex.jpg|thumb|A leaflet of the Dresden Codex written in the [[Mayan Script]] on a type of paper called [[amatl]]. The Dresden Codex is one of only a few examples of [[Mayan civilization|Maya]] Calligraphy to escape the destruction of the Spanish [[Conquistadores]] and survive to the present day.]] |

|||

Mayan calligraphy was expressed via [[Mayan hieroglyphs]]; modern Mayan calligraphy is mainly used on [[Seal (emblem)|seals]] and monuments in the [[Yucatán Peninsula]] in Mexico. Mayan hieroglyphs are rarely used in government offices |

Mayan calligraphy was expressed via [[Mayan hieroglyphs]]; modern Mayan calligraphy is mainly used on [[Seal (emblem)|seals]] and monuments in the [[Yucatán Peninsula]] in Mexico. Mayan hieroglyphs are rarely used in government offices; however in [[Campeche]], [[Yucatán]] and [[Quintana Roo]], Mayan calligraphy is written in Latin letters. Some commercial companies in southern Mexico use Mayan hieroglyphs as symbols of their business. Some community associations and modern Mayan brotherhoods use Mayan hieroglyphs as symbols of their groups. |

||

Most of the archaeological sites in Mexico such as [[Chichen Itza]], Labna, [[Uxmal]], [[Edzna]], [[Calakmul]], etc. have glyphs in their structures. Stone carved monuments also known as [[stele]] are a common |

Most of the archaeological sites in Mexico such as [[Chichen Itza]], Labna, [[Uxmal]], [[Edzna]], [[Calakmul]], etc. have glyphs in their structures. Stone carved monuments also known as [[stele]] are a common sources of ancient Mayan calligraphy. |

||

==Gallery== |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

File:მარიამისეული ქართლის ცხოვრება.JPG|The [[Georgian calligraphy]] is centuries-old tradition of an artistic writing of the [[Georgian language]] with its [[Georgian alphabet|three alphabets]]. |

|||

<!-- > |

|||

Image:Ijazah3.jpg|An [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]] [[ijazah]] written in [[Arabic language|Arabic]] certifying competence in calligraphy, 1206 [[Islamic calendar|AH]]/1791 [[AD]] |

|||

<!-- > |

|||

File:Van yakad.jpg|[[Qur'an]] verses on [[Pictorial carpet]] |

|||

<!-- > |

|||

Image:Chayyam guyand kasan behescht ba hur chosch ast small.png|[[Shikasta Nastaʿlīq]] |

|||

File:Asemic graffiti.jpg|[[Asemic writing]] and abstract calligraphy |

|||

Image:Dresden codex.jpg|A leaflet of the [[Dresden Codex]] written in the Mayan script on a type of paper called ''[[amatl]]''. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

<!--Check to makes sure the wikilink isn't already in one of the navboxes--> |

|||

'''Types of writing''' |

|||

* [[Brāhmī script]] |

|||

* [[Block letters]] — also called printing, is the use of the simple letters children are taught to write when first learning |

|||

* [[Cursive]] — any style of handwriting in which all the letters in a word are connected |

|||

* [[Hand (handwriting)]], in palaeography, refers to a distinct generic style of penmanship |

|||

* [[Handwriting]], a person's particular style of writing by pen or a pencil |

|||

* [[Penmanship]] |

|||

'''Tools''' |

|||

* [[Ink]] |

|||

* [[Paper]] |

|||

* [[Pen]] |

|||

* [[Stylus]] |

|||

'''Related articles''' |

|||

* [[Concrete poetry]] |

* [[Concrete poetry]] |

||

* [[Cursive]] |

|||

* [[List of typographic features]] |

|||

* [[Micrography]] |

* [[Micrography]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Penmanship]] |

||

* [[Sign painting]] |

|||

* [[Emphasis (typography)|Typographic Emphasis]] |

|||

* [[Typographic unit]]s |

|||

* [[Typography]] |

|||

* [[Voynich manuscript]] |

|||

=== Calligraphy museums === |

|||

{{Calligraphy}} |

|||

* [http://calligraphy-museum.com/eng/default.aspx Contemporary museum of calligraphy (Russia)] |

|||

* [http://www.ditchling-museum.com/index.html Ditchling Museum] |

|||

* [http://www.schriftmuseum.at/ Schrift-und Heimatmuseum, Pettenbach (Austria)] |

|||

* [http://www.hmml.org/ Hill Museum & Manuscript Library] |

|||

* [http://www.klingspor-museum.de/UeberdasMuseum.html Klingspor Museum] |

|||

* [http://www.manuscriptcenter.org/museum/ Manuscript Museum of the Library of Alexandria] |

|||

* [http://www.naritakanko.jp/naritashodo/ Naritasan Calligraphy museum]{{dead link|date=October 2013}} |

|||

* [http://muze.sabanciuniv.edu/main/default.php?bytLanguageID=2 Sakip Sabanci Museum]{{dead link|date=October 2013}} |

|||

* [http://www.rain.org/~karpeles/ The Karpeles Manuscript Library Museums] |

|||

* [http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/n/nal-modern-calligraphy/ The Modern Calligraphy Collection of the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum] |

|||

== Notes == |

== Notes == |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist|2}} |

||

== References == |

== References == |

||

[[File:Asemic graffiti.jpg|thumb|[[Asemic writing]] & Abstract calligraphy]] |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Diringer, D.|authorlink=Diringer, D.|year=1968|title=The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind|edition=3rd|volume=1|publisher=Hutchinson & Co.|location=London|page=441}} |

|||

See respective articles. |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Fraser, M.|author2=Kwiatowski, W.|year=2006|title=Ink and Gold: Islamic Calligraphy|publisher=Sam Fogg Ltd.|location=London}} |

|||

* {{citation|title=Learn World Calligraphy: Discover African, Arabic, Chinese, Ethiopic, Greek, Hebrew, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Russian, Thai, Tibetan Calligraphy, and Beyond.|first=Margaret |last = Shepherd |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Johnston, E.|year=1909|title=Manuscript & Inscription Letters: For schools and classes and for the use of craftsmen|chapter=Plate 6|publisher=San Vito Press & Double Elephant Press}} 10th Impression |

|||

|publisher=Crown Publishing Group|year=2013|isbn=082308230X|isbn=9780823082308|page=192}} |

|||

*{{Cite journal| last= Anderson | first=D. M. | year=2008 | title=Indic calligraphy | publisher=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]] 2008 | ref= harv | postscript= <!--None-->}}. |

|||

*Brown, M.P. (2004) Painted Labyrinth: The World of the Lindisfarne Gospel. Revised Ed. British Library. |

|||

*Child, H. ed. (1985) The Calligrapher's Handbook. Taplinger Publishing Co. |

|||

*[[Diringer, D.]] (1968) ''The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind'' 3rd Ed. Volume 1 Hutchinson & Co. London |

|||

*Fraser, M., & Kwiatowski, W. (2006) Ink and Gold: Islamic Calligraphy. Sam Fogg Ltd. London |

|||

*Geddes, A., & Dion, C. (2004) Miracle: a celebration of new life. Photogenique Publishers Auckland. |

|||

*Henning, W.E. (2002) An elegant hand : the golden age of American penmanship and calligraphy ed. Melzer, P. Oak Knoll Press New Castle, Delaware |

|||

*Johnston, E. (1909) Manuscript & Inscription Letters: For schools and classes and for the use of craftsmen, plate 6. San Vito Press & Double Elephant Press 10th Impression |

|||

*Lamb, C.M. ed. (1956) Calligrapher's Handbook. Pentalic 1976 ed. |

|||

*Letter Arts Review |

|||

*[[Claude Mediavilla|Mediavilla, Claude]] (2006) Histoire de la Calligraphie Française. Albin Michel, France. |

|||

*Mediavilla, C. (1996) Calligraphy. Scirpus Publications |

|||

*Pott, G. (2006) Kalligrafie: Intensiv Training Verlag Hermann Schmidt Mainz |

|||

*Pott, G. (2005) Kalligrafie:Erste Hilfe und Schrift-Training mit Muster-Alphabeten Verlag Hermann Schmidt Mainz |

|||

*Propfe, J. (2005) SchreibKunstRaume: Kalligraphie im Raum Verlag George D.W. Callwey GmbH & Co.K.G. Munich |

|||

*Reaves, M., & Schulte, E. (2006) Brush Lettering: An instructional manual in Western brush calligraphy, Revised Edition, Design Books New York. |

|||

*Schimmel, Annemarie. (1984) Calligraphy and Islamic Culture. New York University Press. New York. |

|||

*Zapf, H. (2007) Alphabet Stories: A Chronicle of technical developments, Cary Graphic Arts Press, Rochester, New York |

|||

*Zapf, H. (2006) The world of Alphabets: A kaleidoscope of drawings and letterforms, CD-ROM |

|||

*Marns, F.A (2002) Various, copperplate and form, London |

*Marns, F.A (2002) Various, copperplate and form, London |

||

*{{fr icon}} {{cite book|last=Mediavilla|first=Claude|title=Histoire de la calligraphie française|year=2006|publisher=Michel|location=Paris|isbn=978-2226172839|ref=harv}} |

|||

* Yuuko Suzuki, Japanese Calligraphy, Search Press, 2005. |

|||

* {{cite book|last=Shepherd|first=Margaret |last = Shepherd|title=Learn World Calligraphy: Discover African, Arabic, Chinese, Ethiopic, Greek, Hebrew, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Russian, Thai, Tibetan Calligraphy, and Beyond|publisher=Crown Publishing Group|year=2013|isbn=082308230X|isbn=9780823082308|page=192}} |

|||

*{{cite book | publisher=New York University Press | isbn=9780814778302 | last=Schimmel | first=Annemarie | title=Calligraphy and Islamic Culture |year= 1984}} |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

| Line 253: | Line 199: | ||

* {{dmoz|Arts/Visual_Arts/Calligraphy/}} |

* {{dmoz|Arts/Visual_Arts/Calligraphy/}} |

||

;Calligraphy museums |

|||

* [http://calligraphy-museum.com/eng/default.aspx Contemporary museum of calligraphy (Russia)] |

|||

* [http://www.ditchling-museum.com/index.html Ditchling Museum] |

|||

* [http://www.schriftmuseum.at/ Schrift-und Heimatmuseum, Pettenbach (Austria)] |

|||

* [http://www.hmml.org/ Hill Museum & Manuscript Library] |

|||

* [http://www.klingspor-museum.de/UeberdasMuseum.html Klingspor Museum] |

|||

* [http://www.manuscriptcenter.org/museum/ Manuscript Museum of the Library of Alexandria] |

|||

* [http://www.rain.org/~karpeles/ The Karpeles Manuscript Library Museums] |

|||

* [http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/n/nal-modern-calligraphy/ The Modern Calligraphy Collection of the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum] |

|||

{{Typography terms}} |

{{Typography terms}} |

||

Revision as of 17:06, 31 October 2013

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (October 2013) |

| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

Calligraphy (from Template:Lang-grc kallos "beauty" and γραφή graphẽ "writing") is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a broad tip instrument or brush in one stroke (as opposed to built up lettering, in which the letters are drawn).[1]: 17 A contemporary definition of calligraphic practice is "the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious, and skillful manner".[1]: 18

Modern calligraphy ranges from functional inscriptions and designs to fine-art pieces where the letters may or may not or may not be legible.[1] Classical calligraphy differs from typography and non-classical hand-lettering, though a calligrapher may practice both.[2][3][4][5]

Calligraphy continues to flourish in the forms of wedding and event invitations, font design and typography, original hand-lettered logo design, religious art, announcements, graphic design and commissioned calligraphic art, cut stone inscriptions, and memorial documents. It is also used for props and moving images for film and television, testimonials, birth and death certificates, maps, and other works involving writing.[6][7] Some of the finest works of modern calligraphy are charters and letters patent issued by monarchs and officers of state in various countries.

Western

Tools

The principal tools for a calligrapher are the pen, which may be flat-balled or round-nibbed, and the brush.[8][9][10] Pens may vary from the For some decorative purposes, multi-nibbed pens—steel brushes—can be used. However, works have also been made with felt-tip and ballpoint pens, although these works do not employ angled lines.

Ink for writing is usually water-based and much less viscous than the oil-based inks used in printing. High quality paper, which has good consistency of porosity,[clarification needed] will enable cleaner lines,[citation needed] although parchment or vellum is often used, as a knife can be used to erase work and a light box is not needed to allow lines to pass through it. Normally, light boxes and templates are used to achieve straight lines without pencil markings detracting from the work. Ruled paper, either for a light box or direct use, is most often ruled every quarter or half inch, although inch spaces are occasionally used, such as with litterea unciales (hence the name), and college-ruled paper often acts as a guideline well.[11]

Style

Sacred Western calligraphy has some special features, such as the illumination of the first letter of each book or chapter in medieval times. A decorative "carpet page" may precede the literature, filled with ornate, geometrical depictions of bold-hued animals. The Lindisfarne Gospels (715–720 AD) are an early example.[12]

As with Chinese or Arabic calligraphy, Western calligraphic script had strict rules and shapes. Quality writing had a rhythm and regularity to the letters, with a "geometrical" order of the lines on the page. Each character had, and often still has, a precise stroke order.

Unlike a typeface, irregularity in the characters' size, style, and colors increases aesthetic value, though the content may be illegible. Many of the themes and variations of today's contemporary Western calligraphy are found in the pages of The Saint John's Bible. A particularly modern example is Timothy Botts' illustrated edition of the Bible, with 360 calligraphic images as well as a calligraphy typeface.[13]

History

Western calligraphy is recognizable by the use of the Latin script. The Latin alphabet appeared about 600 BC, in Rome, and by the first century[clarification needed] developed into Roman imperial capitals carved on stones, Rustic capitals painted on walls, and Roman cursive for daily use. In the second and third centuries the uncial lettering style developed. As writing withdrew to monasteries, uncial script was found more suitable for copying the Bible and other religious texts. It was the monasteries which preserved calligraphic traditions during the fourth and fifth centuries, when the Roman Empire fell and Europe entered the Dark Ages.[14]

At the height of the Roman Empire, its power reached as far as Great Britain; when the empire fell, its literary influence remained. The Semi-uncial generated the Irish Semi-uncial, the small Anglo-Saxon. Each region developed its own standards following the main monastery of the region (i.e. Merovingian script, Laon script, Luxeuil script, Visigothic script, Beneventan script), which are mostly cursive and hardly readable.

The rising Carolingian Dynasty Empire encouraged a new standardized script, which was developed by several famous monasteries (including Corbie Abbey and Beauvais) around the eighth century. The script from Saint Martin of Tours was ultimately set as the Imperial standard, named the Carolingian script (or "the Caroline"). From the powerful Carolingian Empire, this standard also became used in neighboring kingdoms.

In the eleventh century, the Caroline evolved into the Gothic script, which was more compact and made it possible to fit more text on a page.[15]: 72 The Gothic calligraphy styles became dominant throughout Europe; and in 1454, when Johannes Gutenberg developed the first printing press in Mainz, Germany, he adopted the Gothic style, making it the first typeface.[15]: 141

In the 15th century, the rediscovery of old Carolingian texts encouraged the creation of the humanist minuscule or littera antiqua. The 17th century saw the Batarde script from France, and the 18th century saw the English script spread across Europe and world through their books.

Contemporary typefaces used by computers, from word processors like Microsoft Word or Apple Pages to professional designers' software like Adobe InDesign, owe a considerable debt to the past and to a small number of professional typeface designers today.[1][4][16]

Influences

Several other Western styles use the same tools and practices, but differ by character set and stylistic preferences. For Slavonic lettering, the history of the Slavonic and consequently Russian writing systems differs fundamentally from the one of the Latin language. It evolved from the 10th century to today.

East Asian

The Chinese name for calligraphy is shūfǎ (書法 in Taiwanese, literally "the method or law of writing");[17] the Japanese name shodō (書道, literally "the way or principle of writing"); the Korean is seoye (Template:Lang-ko, literally "the art of writing"); and the Vietnamese is [Thư pháp] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: vt (help) (書法, literally "the way of letters or words"). The calligraphy of East Asian characters is an important and appreciated aspect of East Asian culture.

Technique

Traditional East Asian writing uses the Four Treasures of the Study (文房四寶 in Taiwanese and 文房四宝 in Cantonese): the ink brushes to write Chinese characters, Chinese ink, paper, and inkstone, known as the Four Friends of the Study (Template:Lang-ko) in Korea. In addition to these four tools, desk pads and paperweights are also used.

The shape, size, stretch, and hair type of the ink brush, the color, color density and water density of the ink, as well as the paper's water absorption speed and surface texture are the main physical parameters influencing the final result. The calligrapher also influences the result by the quantity of ink and water he lets the brush take, then by the pressure, inclination, and direction he gives to the brush, producing thinner or bolder strokes, and smooth or toothed borders. Eventually, the speed, accelerations, decelerations of the writer's moves, turns, and crochets, and the stroke order give the "spirit" to the characters, by influencing greatly their final shapes.

History

China

In ancient China, the oldest Chinese characters existing are Jiǎgǔwén characters carved on ox scapulae and tortoise plastrons, because the dominators in Shang Dynasty carved pits on such animalss' bones and then baked them to gain auspice of military affairs, agricultural harvest, or even procreating and weather. During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made, the characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved.(Keightley, 1978). With the development of Jīnwén (Bronzeware script) and Dàzhuàn (Large Seal Script) "cursive" signs continued. Moreover, each archaic kingdom of current China had its own set of characters.

In Imperial China, the graphs on old steles — some dating from 200 BC, and in Xiaozhuan style — are still accessible.

About 220 BC, the emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first to conquer the entire Chinese basin, imposed several reforms, among them Li Si's character unification, which created a set of 3300 standardized Xiǎozhuàn characters.[18] Despite the fact that the main writing implement of the time was already the brush, few papers survive from this period, and the main examples of this style are on steles.

The Lìshū style (clerical script) which is more regularized, and in some ways similar to modern text, have been also authorised under Qin Shi Huangdi.[19]

Kǎishū style (traditional regular script) — still in use today — and attributed to Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303–361) and his followers, is even more regularized.[19] Its spread was encouraged by Emperor Mingzong of Later Tang (926–933), who ordered the printing of the classics using new wooden blocks in Kaishu. Printing technologies here allowed a shape stabilization. The Kaishu shape of characters 1000 years ago was mostly similar to that at the end of Imperial China.[19] But small changes have be made, for example in the shape of 广 which is not absolutely the same in the Kangxi Dictionary of 1716 as in modern books. The Kangxi and current shapes have tiny differences, while stroke order is still the same, according to old style.[20]

Styles which did not survive include Bāfēnshū, a mix made of Xiaozhuan style at 80%, and Lishu at 20%.[19] Some variant Chinese characters were unorthodox or locally used for centuries. They were generally understood but always rejected in official texts. Some of these unorthodox variants, in addition to some newly created characters, compose the Simplified Chinese character set.

Styles

Cursive styles such as xíngshū (semi-cursive or running script) and cǎoshū (cursive or grass script) are less constrained and faster, where more movements made by the writing implement are visible. These styles' stroke orders vary more, sometimes creating radically different forms. They are descended from Clerical script, in the same time as Regular script (Han Dynasty), but xíngshū and cǎoshū were used for personal notes only, and never used as a standard. The cǎoshū style was highly appreciated in Emperor Wu of Han reign (140–187 AD).[19]

Examples of modern printed styles are Song from the Song Dynasty's printing press, and sans-serif. These are not considered traditional styles, and are normally not written.

Influences

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2013) |

Japanese and Korean people developed specific sensibilities and styles of calligraphy. For example, Japanese calligraphy go out of the set of CJK strokes to also include local alphabets such as hiragana and katakana, with specific problematics such as new curves and moves, and specific materials (Japanese paper, washi 和紙, and Japanese ink).[21] In the case of Korean calligraphy, the Hangeul and the existence of the circle required the creation of a new technique which usually confuses Chinese calligraphers.

Temporary calligraphy is a practice of water-only calligraphy on the floor, which dries out within minutes. This practice is especially appreciated by the new generation of retired Chinese in public parks of China. These will often open studio-shops in tourist towns offering traditional Chinese calligraphy to tourists. Other than writing the clients name, they also sell fine brushes as souvenirs and lime stone carved stamps.

Since late 1980's a few Chinese artists have branched out traditional Chinese calligraphy to a new territory by mingling Chinese characters with English letters; notable new forms of calligraphy are Xu Bing's square calligraphy and DanNie's coolligraphy or cooligrapgy.

Mongolian calligraphy is also influenced by Chinese calligraphy, from tools to style.

Calligraphy has influenced ink and wash painting, which is accomplished using similar tools and techniques. Calligraphy has influenced most major art styles in East Asia, including ink and wash painting, a style of Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, Japanese painting, and Vietnamese painting based entirely on calligraphy.

South Asian

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2013) |

Indian

This section contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (October 2013) |

On the subject of Indian calligraphy, writes:[22]

Aśoka's edicts (c. 265–238 BC) were committed to stone. These inscriptions are stiff and angular in form. Following the Aśoka style of Indic writing, two new calligraphic types appear: Kharoṣṭī and Brāhmī. Kharoṣṭī was used in the northwestern regions of India from the 3rd century BC to the 4th century of the Christian Era, and it was used in Central Asia until the 8th century.

In many parts of ancient India, the inscriptions were carried out in smoke-treated palm leaves. This tradition dates back to over two thousand years.[23] Even after the Indian languages were put on paper in the 13th century, palm leaves where considered a preferred medium of writing owing to its longevity (nearly 400 years) compared to paper. Both sides of the leaves were used for writing. Long rectangular strips were gathered on top of one another, holes were drilled through all the leaves, and the book was held together by string. Books of this manufacture were common to Southeast Asia. The palm leaf was an excellent surface for penwriting, making possible the delicate lettering used in many of the scripts of southern Asia.

Burnt clay and copper were a favoured material for Indic inscriptions.[citation needed] In the north of India, birch bark was used as a writing surface as early as the 2nd century AD.[citation needed].

Nepalese

Ranjana script is the primary form of Nepalese calligraphy. The script itself, along with its derivatives (like Lantsa, Phagpa, Kutila) are used in Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, Leh, Mongolia, coastal China, Japan, and Korea to write "Om mani padme hum" and other sacred Buddhist texts, mainly those derived from Sanskrit and Pali.

Tibetan calligraphy

Calligraphy is central in Tibetan culture. The script is derived from Indic scripts. The nobles of Tibet, such as the High Lamas and inhabitants of the Potala Palace, were usually capable calligraphers. Tibet has been a center of Buddhism for several centuries, and that religion places a great deal of significance on written word. This does not provide for a large body of secular pieces, although they do exist (but are usually related in some way to Tibetan Buddhism). Almost all high religious writing involved calligraphy, including letters sent by the Dalai Lama and other religious and secular authority. Calligraphy is particularly evident on their prayer wheels, although this calligraphy was forged rather than scribed, much like Arab and Roman calligraphy is often found on buildings. Although originally done with a reed, Tibetan calligraphers now use chisel tipped pens and markers as well.

Islamic

Islamic calligraphy (calligraphy in Arabic is khatt ul-yad Template:Rtl-lang) has evolved alongside Islam]] and the [[Arabic language. As it is based on Arabic letters, some call it "Arabic calligraphy". However the term "Islamic calligraphy" is a more appropriate term as it comprises all works of calligraphy by the Muslim calligraphers from Andalusia in modern Spain to China.

Islamic calligraphy is associated with geometric Islamic art (arabesque) on the walls and ceilings of mosques as well as on the page. Contemporary artists in the Islamic world draw on the heritage of calligraphy to use calligraphic inscriptions or abstractions.

Instead of recalling something related to the spoken word, calligraphy for Muslims is a visible expression of the highest art of all, the art of the spiritual world. Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The Qur'an has played an important role in the development and evolution of the Arabic language, and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. Proverbs and passages from the Qur'an are still sources for Islamic calligraphy.

It is generally accepted that Islamic calligraphy excelled during the Ottoman era. Turkish calligraphers still present the most refined and creative works. Istanbul is an open exhibition hall for all kinds and varieties of calligraphy, from inscriptions in mosques to fountains, schools, houses, etc.

Persian

The history of calligraphy in Persia dates back to the pre-Islam era. In Zoroastrianism beautiful and clear writings were always praised.

It is believed that ancient Persian script was invented by about 600–500 BC to provide monument inscriptions for the Achaemenid kings. These scripts consisted of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal nail-shape letters, which is why it is called "script of nails/cuneiform script" (khat-e-mikhi) in Persian. Centuries later, other scripts such as "Pahlavi" and "Avestan" scripts were used in ancient Persia.

After the Arab conquest in the 7th century, Persians adapted the Arabic alphabet to fit the Persian language, which developed into the modern Persian alphabet. The Arabic alphabet has 28 characters, to which Iranians added another four letters to account for sounds and letters in Persian that do not exist in Arabic.

Contemporary scripts

Nasta'liq is the most popular contemporary style among classical Persian calligraphy scripts; Persian calligraphers call it the "bride of calligraphy scripts". This calligraphy style has been based on such a strong structure that it has changed very little since. Mir Ali Tabrizi had found the optimum composition of the letters and graphical rules so it has just been fine-tuned during the past seven centuries. It has very strict rules for graphical shape of the letters and for combination of the letters, words, and composition of the whole calligraphy piece.

Mayan

Mayan calligraphy was expressed via Mayan hieroglyphs; modern Mayan calligraphy is mainly used on seals and monuments in the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Mayan hieroglyphs are rarely used in government offices; however in Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo, Mayan calligraphy is written in Latin letters. Some commercial companies in southern Mexico use Mayan hieroglyphs as symbols of their business. Some community associations and modern Mayan brotherhoods use Mayan hieroglyphs as symbols of their groups.

Most of the archaeological sites in Mexico such as Chichen Itza, Labna, Uxmal, Edzna, Calakmul, etc. have glyphs in their structures. Stone carved monuments also known as stele are a common sources of ancient Mayan calligraphy.

Gallery

-

The Georgian calligraphy is centuries-old tradition of an artistic writing of the Georgian language with its three alphabets.

-

Qur'an verses on Pictorial carpet

-

Asemic writing and abstract calligraphy

-

A leaflet of the Dresden Codex written in the Mayan script on a type of paper called amatl.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d Mediaville, Claude (1996). Calligraphy: From Calligraphy to Abstract Painting. Belgium: Scirpus-Publications. ISBN 9080332518.

- ^ Template:De icon Pott, G. (2006). Kalligrafie: Intensiv Training. Verlag Hermann Schmidt. ISBN 9783874397001.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:De icon Pott, G. (2005). Kalligrafie: Erste Hilfe und Schrift-Training mit Muster-Alphabeten. Verlag Hermann Schmidt. ISBN 9783874396752.

- ^ a b Zapf, H. (2007). Alphabet Stories: A Chronicle of technical developments. Rochester, New York: Cary Graphic Arts Press. ISBN 9781933360225.

- ^ Zapf, H. (2006). The world of Alphabets: A kaleidoscope of drawings and letterforms. CD-ROM

- ^ Template:De icon Propfe, J. (2005). SchreibKunstRaume: Kalligraphie im Raum Verlag. Munich: George D.W. Callwey GmbH & Co.K.G. ISBN 9783766716309.

- ^ Geddes, A.; Dion, C. (2004). Miracle: a celebration of new life. Auckland: Photogenique Publishers. ISBN 9780740746963.

{{cite book}}: Missing|author2=(help) - ^ Reaves, M.; Schulte, E. (2006). Brush Lettering: An instructional manual in Western brush calligraphy (Revised ed.). New York: Design Books.

- ^ Child, H., ed. (1985). The Calligrapher's Handbook. Taplinger Publishing Co.

- ^ Lamb, C.M., ed. (1976) [1956]. Calligrapher's Handbook. Pentalic.

- ^ "Calligraphy Islamic website". Calligraphyislamic.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ^ Brown, M.P. (2004). Painted Labyrinth: The World of the Lindisfarne Gospel (Revised Ed ed.). British Library.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ The Bible: New Living Translation. Tyndale House Publishers. 2000.

- ^ Template:Fr icon Sabard, V.; Geneslay, V.; Rébéna, L. (2004). Calligraphie latine: Initiation (7th ed.). Fleurus, Paris. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-2215021308.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Lovett, Patricia (2000). Calligraphy and Illumination: A History and Practical Guide. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810941199.

- ^ Henning, W.E. (2002). Melzer, P. (ed.). An Elegant Hand: The Golden Age of American Penmanship and Calligraphy. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press. ISBN 978-1584560678.

- ^ 書 (Taiwanese) being here used as in 楷书 (Cantonese) or 楷書 (Taiwanese), meaning "writing style".[clarification needed]

- ^ Fazzioli, Edoardo (1987). Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History Of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters. Calligraphy by Rebecca Hon Ko. New York: Abbeville Press. p. 13. ISBN 0896597741.

And so the first Chinese dictionary was born, the Sān Chāng, containing 3,300 characters