Islamic calligraphy: Difference between revisions

→Calligrams: Hide section with bad references. |

|||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

# '''[[Sini (script)|Sini]]''' is a style developed in China. The shape is greatly influenced by [[Chinese calligraphy]], using a horsehair brush instead of the standard reed pen. A famous modern calligrapher in this tradition is [[Hajji]] [[Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang]].<ref>[http://www.hajinoordeen.com/gallery.html "Gallery"], ''Haji Noor Deen''.</ref> |

# '''[[Sini (script)|Sini]]''' is a style developed in China. The shape is greatly influenced by [[Chinese calligraphy]], using a horsehair brush instead of the standard reed pen. A famous modern calligrapher in this tradition is [[Hajji]] [[Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang]].<ref>[http://www.hajinoordeen.com/gallery.html "Gallery"], ''Haji Noor Deen''.</ref> |

||

==Calligrams== |

<!--==Calligrams== |

||

[[File:Mogultughra.jpg|thumb|leftThe official imperial [[Tughra]] of the [[Mughal Empire]].]] |

[[File:Mogultughra.jpg|thumb|leftThe official imperial [[Tughra]] of the [[Mughal Empire]].]] |

||

[[File:The Bismillah India.jpg|thumb|Bismillah calligraphy from the [[Mughal Empire]].]] |

[[File:The Bismillah India.jpg|thumb|Bismillah calligraphy from the [[Mughal Empire]].]] |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

One of the contemporary masters of the calligram genre is [[Hassan Massoudy]] and [[Wissam Shawkat]]. |

One of the contemporary masters of the calligram genre is [[Hassan Massoudy]] and [[Wissam Shawkat]]. |

||

Good commercial examples are the logos of [[Al Jazeera]], an international news station based at [[Qatar]], and the [[Edinburgh Middle East Report]], a Scottish academic journal on the [[Middle East]], and also the work of the calligrapher and designer Wissam Shawkat. |

Good commercial examples are the logos of [[Al Jazeera]], an international news station based at [[Qatar]], and the [[Edinburgh Middle East Report]], a Scottish academic journal on the [[Middle East]], and also the work of the calligrapher and designer Wissam Shawkat.--> |

||

== Instruments and media== |

== Instruments and media== |

||

Revision as of 12:48, 5 May 2014

| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

Islamic calligraphy, also known as Arabic calligraphy, is the artistic practice of handwriting, calligraphy, and by extension, of bookmaking,[1]: 218 in the lands sharing a common Islamic cultural heritage. It is known in Arabic as khatt (خط), which derived from the word 'line', 'design', or 'construction'.[2]

This art form is based on the Arabic script, which is used to some extend by all Muslims in their respective languages. Suspicion of figurative art as idolatrous led calligraphy and abstract depictions to become a major form of artistic expression in Islamic cultures, particularly in religious contexts.[1]: 222 Due to its deep association with writing and preserving the Qur'an, calligraphy is highly esteemed among other forms of visual Islamic art.[3]

Styles

Kufic

Kufic is the oldest form of the Arabic script. The style emphasizes rigid and angular strokes, which appears as a modified form of the old Nabataean script. The Archaic Kufi consisted of about 17 letters without diacritic dots or accents. Afterwards, dots and accents were added to help readers with pronunciation, and the set of Arabic letters rose to 29.[4] It is developed around the end of the 7th century in the areas of Kufa, Iraq, from which it takes its name.[5] The style later developed into several varieties, including floral, foliated, plaited or interlaced, bordered, and squared kufi. It was the main script used to copy Qur'ans from the 8th to 10th century and went out of general use in the 12th century when the flowing naskh style become more practical, although it continued to be used as a decorative element to contrast superseding styles.[6]

There were no set rules of using the Kufic script; the only common feature is the angular, linear shapes of the characters. Due to the lack of methods, the scripts in different regions and countries and even down to the individuals themselves have different ways to write in the script creatively, ranging from very square and rigid forms to flowery and decorative.[7] Common varieties includes:

- Maghribi (Moroccan or western) kufic is a slight modification of early Kufic. It features a significant amount of curves and loops as opposed to the original Arabic kufic script. loops for the characters such as the Waw and the Meem are pronounced and perhaps more exaggerated.[7]

- Fatimi (or eastern) kufic is prevalent in the North African region, particularly in Egypt. The stylized and decorative form was mainly used in the decoration of buildings.[7]

- Murabba (or square) kufic is absolutely straight with no decorative accents or curves. Due to this rigidity, this type of script can be created using square tiles or bricks.[7] In Iran, entire buildings may be covered with tiles spelling sacred names like those of God, Muhammad and Ali in square Kufic, a technique known as banna'i.[8] Contemporary calligraphy using this style is also popular in modern decorations.[7]

Decorative kufic inscriptions are often imitated into pseudo-kufics in Middle age And Renaissance Europe. Pesudo-kufics is especially common in Renaissance depictions of people from the Holy Land. The exact reason for the incorporation of pseudo-Kufic is unclear. It seems that Westerners mistakenly associated 13–14th century Middle-Eastern scripts as being identical with the scripts current during Jesus's time, and thus found natural to represent early Christians in association with them.[9]

Naskh

The use of cursive script coexisted with kufic, but because in the early stages of their development they lacked discipline and elegance, cursive were usually used for informal purposes.[10] With the rise of Islam, new script was needed to fit the pace of conversions, and a well defined cursive called naskh first appeared in the 10th century. The script is the most ubiquitous among other styles, used in Qur’ans, official decrees, and private correspondence.[11] It become the basis of modern Arabic print.

Standardization of the style was pioneered by Ibn Muqla (886-940 A.D.) and later discussed by Abu Hayan at-Tawhidi (died 1009 A.D.) and Muhammad Ibn Abd ar-Rahman (1492-1545 A.D.). Ibn Muqla is highly regarded in Muslim sources on calligraphy as the inventor of the naskh style, although it seems to be erroneous. However, Ibn Muqla did established systematic rules and proportions for shaping the letters, which use 'alif as the x-height.[12]

Variation of the naskh includes:

- Thuluth is developed as a display script to decorate particular scriptural objects. Letters have long vertical lines, rarely stacks with each other with broad spacing. The name reference to the x-height, which is one third of the alif.[2]

- Riq'ah is a handwriting style derived from naskh and thuluth, first appeared in the 9th century. The shape is simple with short strokes and little flourishes.[2]

- Muhaqqaq is a majestic style used by accomplished calligrapher. It was considered one of the most beautiful script, as well as one of the most the difficult to execute. It is commonly used during the mamluk era, but the use become largely restricted to short phrases, such as basmallah, from the 18th century onward.[13]

Regional

With the spread of Islam, the Arabic script was established in a vast geographic area with many regions developing their own unique style. From the 14th century onward, other cursive styles began to developed in Turkey, Persia, and China.[11]

- Nasta'liq is a cursive style originally devised to write the Persian language for literary and non-Qur'anic works.[14] Nasta'liq is thought to be a latter developement of the naskh and the earlier ta'liq script used in Iran.[15] The name ta'liq means 'hanging', and refers to the slightly steeped lines of which words run in, giving the script a hanging appearance. Letters have short vertical strokes with broad and sweeping horizontal strokes. The shapes are deep, hook-like, and have high contrast.[14] A variant called Shikasteh is used in a more informal contexts.

- Diwani is a cursive style of Arabic calligraphy developed during the reign of the early Ottoman Turks in the 16th and early 17th centuries. It was invented by Housam Roumi and reached its height of popularity under Süleyman I the Magnificent (1520–1566).[16] Spaces between letters are often narrow, and lines ascend upwards from right to left. Larger variation called djali are filled with dense decorations of dots and diacritical marks in the space between, giving it a compact appearance. Diwani is difficult to read and write due to its heavy stylization, and became ideal script for writing court documents as it insured confidentiality and prevented forgery.[14]

- Sini is a style developed in China. The shape is greatly influenced by Chinese calligraphy, using a horsehair brush instead of the standard reed pen. A famous modern calligrapher in this tradition is Hajji Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang.[17]

Instruments and media

The traditional instrument of the Arabic calligrapher is the qalam, a pen made of dried reed or bamboo; the ink is often in color, and chosen such that its intensity can vary greatly, so that the greater strokes of the compositions can be very dynamic in their effect.

The Islamic calligraphy is applied on a wide range of decorative mediums other than paper, such as tiles, vessels, carpets, and inscriptions.[3] Before the advent of paper, papyrus and parchment were used for writing. The advent of paper revolutionized calligraphy. While monasteries in Europe treasured a few dozen volumes, libraries in the Muslim world regularly contained hundreds and even thousands of volumes of books.[1]: 218

Coins were another support for calligraphy. Beginning in 692, the Islamic caliphate reformed the coinage of the Near East by replacing visual depiction by words. This was especially true for dinars, or gold coins of high value. Generally the coins were inscribed with quotes from the Qur'an.

By the tenth century, the Persians, who had converted to Islam, began weaving inscriptions on to elaborately patterned silks. So precious were calligraphic inscribed textile that Crusaders brought them to Europe as prized possessions. A notable example is the Suaire de Saint-Josse, used to wrap the bones of St. Josse in the abbey of St. Josse-sur-Mer near Caen in northwestern France.[1]: 223–5

Mosque calligraphy

Islamic Mosque calligraphy is calligraphy that can be found in and out of a mosque, typically in combination with Arabesque motifs. Arabesque is a form of Islamic art known for its repetitive geometric forms creating beautiful decorations. These geometric shapes often include Arabic calligraphy written on walls and ceilings inside and outside of mosques.

The subject of these writings can be derived from different sources in Islam. It can be derived from the written words of the Qur'an or from the oral traditions relating to the words and deeds of Islamic Prophet Muhammad.

There is a beautiful harmony between the inscriptions and the functions of the mosque. Specific surahs (chapters) or ayats (verses) from Koran are inscribed in accordance with functions of specific architectural elements. For example, on the domes you can find the Nour ayat (the divine stress on light) written, above the main entrance you find verses related to the entrances of the paradise, on the windows the divine names of Allah are inscribed so that reflection of the sun rays through those windows remind the believer that Allah manifests Himself upon the universe in all high qualities.[citation needed]

Gallery

-

Page of an Ilkhanid Qur'an (13th Century)

-

Bismillah calligraphy in Sini script

-

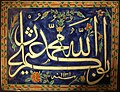

Bismillah calligraphy

-

Bismillah calligraphy

-

Bismillah calligraphy in Kufic script, Cairo 9th century

-

Qur'an folio 11th century kufic

-

Islamic calligraphy in Hagia Sophia

-

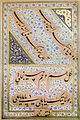

Qur'anic Manuscript - Mid to Late 15th Century, Turkey

-

Maghribi script

-

Calligraphic writing on a fritware tile, depicting the names of God, Muhammad and the first caliphs. Istanbul, Turkey, c. 1727

-

Naskh Basmala

-

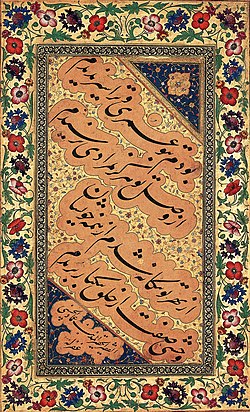

Manuscript between 1500 and 1599

-

Calligraphy in Nasta'liq Script

-

Ottoman manuscript in Ta'liq Script.

-

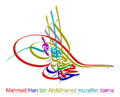

The stylized signature (tughra) of Sultan Mahmud II of the Ottoman Empire was written in an expressive calligraphy. It reads Mahmud Khan son of Abdulhamid is forever victorious.

-

Animation showing the calligraphic composition of the Al Jazeera logo.

-

An example of zoomorphic calligraphy

-

The Emirates logo is written in traditional Arabic calligraphy

-

The instruments and work of a student calligrapher.

-

Islamic calligraphy performed by a Malay Muslim in Malaysia. Calligrapher is making a rough draft.

-

Jawi script written with Islamic calligraphy on the signboard of a royal mausoleum in Kelantan (a state in Malaysia). The signboard reads "Makam Diraja Langgar".

See also

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic Golden Age

- Islamic graffiti

- Islamic pottery

- Ottoman Turkish language

- Persian calligraphy

- Sini (script)

List of calligraphers

Some classical calligraphers:

- Ibn Muqla (d. 939/940)

- Ibn al-Bawwab (d. 1022)

- Yaqut al-Musta'simi (d. 1298)

- Mir Ali Tabrizi (d. 14th-15th century)

- Şeyh Hamdullah (1436–1520)

- Seyyid Kasim Gubari (d. 1624)

- Hâfiz Osman (1642–1698)

References

- ^ a b c d Blair, Sheila S. (1995). The art and architecture of islam : 1250-1800 (Reprinted with corrections. ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300064659.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Julia Kaestle (10 July 2010). "Arabic calligraphy as a typographic exercise".

- ^ a b Chapman, Caroline (2012). Ensiklopedi Seni dan Arsitektur Islam , ISBN 9789790996311

- ^ "History of the Arabic Type Evolution from 1930 till Present".

- ^ "Arabic scripts". British Museum. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Kūfic script".

- ^ a b c d e "History – The Kufic Script".

- ^ Jonathan M. Bloom; Sheila Blair (2009). The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture. Oxford University Press. pp. 101, 131, 246. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Mack, Rosamond E. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600, University of California Press, 2001 ISBN 0-520-22131-1

- ^ Mamoun Sakkal (1993). "The Art of Arabic Calligraphy, a brief history".

- ^ a b "Library of Congress, Selections of Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Calligraphy: Qur'anic Fragments". International.loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ^ Kampman, Frerik (2011). [Arabic Typograhy; its past and its future]

- ^ Mansour, Nassar (2011). Sacred Script: Muhaqqaq in Islamic Calligraphy. New York: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84885-439-0

- ^ a b c "An Introduction of Arabic, Ottoman, and Persian Calligraphy: Styles".

- ^ "Ta'liq Script".

- ^ "Diwani script".

- ^ "Gallery", Haji Noor Deen.

![Example showing Nastaʿlīq's (Persian) proportion rules.[ 1 ]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0c/Nastaliq-proportions.jpg/115px-Nastaliq-proportions.jpg)