Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust: Difference between revisions

Nihil novi (talk | contribs) editing the lead |

Nihil novi (talk | contribs) →Partial list of communities: copyedit |

||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

The Home Army units under the command of officers from left-wing [[Sanacja]], the [[Polish Socialist Party|PPS]] as well as the centrist [[Democratic Party (Poland)|Democratic Party]] welcomed Jewish fighters to serve with Poles without problems stemming from their ethnic identity. As noted by [[Joshua D. Zimmerman]], many negative stereotypes about the Home Army among the Jews came from reading postwar literature on the subject, and not from personal experience.<ref name="huji33"/> In spite of Polish Jewish representation in the London-based government in exile, some rightist units of the Armia Krajowa – as noted by [[Joanna B. Michlic]] – exhibited ethno-nationalism that excluded Jews. Similarly, some members of the Delegate's Bureau saw Jews and ethnic Poles as separate entities.<ref name="google34"/> Historian [[Israel Gutman]] has noted that AK leader [[Stefan Rowecki]] advocated the abandonment of the long-range considerations of the underground and the launch of an all-out uprising should the Germans undertake a campaign of extermination against ethnic Poles, but that no such plan existed while the extermination of Jewish Polish citizens was under way.<ref name="google35"/> On the other hand, not only the pre-war Polish government armed and trained Jewish paramilitary groups such as [[Lehi (group)|Lehi]] but also – while in exile – accepted thousands of Polish Jewish fighters into [[Anders Army]] including leaders such as [[Menachem Begin]]. The policy of support continued throughout the war with the [[Jewish Combat Organization]] and the [[Jewish Military Union]] forming an integral part of the Polish resistance.<ref name="FocusPl"/> |

The Home Army units under the command of officers from left-wing [[Sanacja]], the [[Polish Socialist Party|PPS]] as well as the centrist [[Democratic Party (Poland)|Democratic Party]] welcomed Jewish fighters to serve with Poles without problems stemming from their ethnic identity. As noted by [[Joshua D. Zimmerman]], many negative stereotypes about the Home Army among the Jews came from reading postwar literature on the subject, and not from personal experience.<ref name="huji33"/> In spite of Polish Jewish representation in the London-based government in exile, some rightist units of the Armia Krajowa – as noted by [[Joanna B. Michlic]] – exhibited ethno-nationalism that excluded Jews. Similarly, some members of the Delegate's Bureau saw Jews and ethnic Poles as separate entities.<ref name="google34"/> Historian [[Israel Gutman]] has noted that AK leader [[Stefan Rowecki]] advocated the abandonment of the long-range considerations of the underground and the launch of an all-out uprising should the Germans undertake a campaign of extermination against ethnic Poles, but that no such plan existed while the extermination of Jewish Polish citizens was under way.<ref name="google35"/> On the other hand, not only the pre-war Polish government armed and trained Jewish paramilitary groups such as [[Lehi (group)|Lehi]] but also – while in exile – accepted thousands of Polish Jewish fighters into [[Anders Army]] including leaders such as [[Menachem Begin]]. The policy of support continued throughout the war with the [[Jewish Combat Organization]] and the [[Jewish Military Union]] forming an integral part of the Polish resistance.<ref name="FocusPl"/> |

||

==Towns and villages== |

|||

==Partial list of communities== |

|||

Below is |

Below is a partial list of Polish communities that collectively rescued Jews during the [[Jewish Holocaust]]. The spelling of some towns, villages, and counties has been revised in accord with current data. Occasionally the links lead to disambiguation pages listing villages of the same name in the same area of [[Second Polish Republic|prewar]] or postwar Poland.<ref name="Mark Paul" /> |

||

<small>'''For list of |

<small>'''For list of towns, villages, and their locations in alphabetical order, please use the table-sort buttons.'''</small> |

||

{| class="wikitable sortable" style="width:98%; float:left; background:#fff; font-size:92%; border:0 solid #a3bfb1; color:#000;" |

{| class="wikitable sortable" style="width:98%; float:left; background:#fff; font-size:92%; border:0 solid #a3bfb1; color:#000;" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

Revision as of 09:13, 25 May 2018

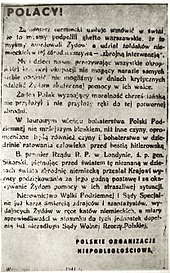

| Death penalty for the rescue of Jews in occupied Poland | |

|---|---|

| Public announcement | |

| |

Concerning: According to this decree, those knowingly helping these Jews by providing shelter, supplying food, or selling them foodstuffs are also subject to the death penalty This is a categorical warning to the non-Jewish population against: Częstochowa, 24.9.42 Dr. Franke |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Jews and Judaism in Poland |

|---|

| Historical Timeline • List of Jews |

|

|

Polish Jews were the primary victims of the German-organized Holocaust. Throughout the German occupation of Poland, some Poles risked their lives – and the lives of their families – to rescue Jews from the Germans. Poles were, by nationality, the most numerous persons who rescued Jews during the Holocaust.[1][2] To date, 7,232[3] ethnic Poles have been recognized by the State of Israel as Righteous among the Nations – more, by far, than the citizens of any other country.[1]

The Home Army (the Polish Resistance) alerted the world to the Holocaust through the reports of Polish Army officer Witold Pilecki, conveyed by Polish Government-in-Exile courier Jan Karski. The Polish Government-in-Exile and the Polish Secret State pleaded, to no avail, for American and British help to stop the Holocaust.[4]

Some estimates put the number of Polish rescuers of Jews as high as 3 million, and credit Poles with saving up to some 450,000 Jews, at least temporarily, from certain death.[2] The rescue efforts were aided by one of the largest resistance movements in Europe, the Polish Underground State and its military arm, the Home Army. Supported by the Government Delegation for Poland, these organizations operated special units dedicated to helping Jews; of those units, the most notable was the Żegota Council, based in Warsaw, with branches in Kraków, Wilno, and Lwów.[5]

Polish rescuers of Jews were hampered by the most stringent conditions in all of German-occupied Europe. Occupied Poland was the only country where the Germans decreed that any kind of help to Jews was punishable by death for the rescuer and the rescuer's entire family.[6] Of the estimated 3 million non-Jewish Poles killed in World War II, thousands – perhaps as many as 50,000 – were executed by the Germans solely for saving Jews.[2]

Background

Before World War II, 3,300,000 Jewish people lived in Poland – ten percent of the general population of some 33 million. Poland was the center of the European Jewish world.[7]

The Second World War began with the Nazi German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939; and, on 17 September, in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement, the Soviet Union attacked Poland from the east. By October 1939, the Second Polish Republic was split in half between two totalitarian powers. Germany occupied 48.4 percent of western and central Poland.[8] Racial policy of Nazi Germany regarded Poles as "sub-human" and Polish Jews beneath that category, validating a campaign of unrestricted violence. One aspect of German foreign policy in conquered Poland was to prevent its ethnically diverse population from uniting against Germany.[9][10] The Nazi plan for Polish Jews was one of concentration, isolation, and eventually total annihilation in the Holocaust also known as the Shoah. Similar policy measures toward the Polish Catholic majority focused on the murder or suppression of political, religious, and intellectual leaders as well as the Germanization of the annexed lands which included a program to resettle Germans from the Baltics and other regions onto farms, ventures and homes formerly owned by the expelled Poles including Polish Jews.[11]

The response of the Polish majority to the Jewish Holocaust covered an extremely wide spectrum, often ranging from acts of altruism at the risk of endangering their own and their families’ lives, through compassion, to passivity, indifference, and blackmail.[13] Polish rescuers faced threats from unsympathetic neighbours, the Polish-German Volksdeutsche,[13] the ethnic Ukrainian pro-Nazis,[14] as well as blackmailers called szmalcowniks, along with the Jewish collaborators from Żagiew and Group 13. The Catholic saviors of Jews were also betrayed under duress by the Jews in hiding following capture by the German military police, which resulted in the Nazi murder of the entire networks of Polish helpers.[15] Holocaust testimonies confirm that, trapped in the ghettos, the Jewish criminal underworld took advantage of inside information about the socio-economic standing of their own compatriots. The Jewish looters knew better than anyone else "where to dig for valuables" wrote Isaiah Trunk and Rubin Katz.[16] Nevertheless, statistics of the Israeli War Crimes Commission indicate that less than one tenth of 1 per cent of native Poles collaborated with the occupiers.[17]

In 1941, at the onset of German-Soviet war, the main architect of the Holocaust, Reinhard Heydrich, issued his operational guidelines for the mass anti-Jewish actions carried out with the participation local gentiles.[18] Massacres of Polish Jews by the Ukrainian and Lithuanian auxiliary battalions followed.[19] Deadly pogroms were committed in over 30 locations across formerly Soviet-occupied parts of Poland,[20] including in Brześć, Tarnopol, Białystok, Łuck, Lwów, Stanisławów, and in Wilno where the Jews were murdered along with the Poles in the Ponary massacre at a ratio of 3-to-1.[21][22] National minorities routinely participated in pogroms led by OUN-UPA, YB, TDA and BKA.[23][24][25][26][27] Local participation in the Nazi German "cleansing" operations included the Jedwabne pogrom of 1941.[28][29] The Einsatzkommandos were ordered to organize them in all eastern territories occupied by Germany. Less than one tenth of 1 per cent of native Poles collaborated, according to statistics of the Israeli War Crimes Commission.[17]

Non–Jewish Poles provided assistance to the Jews in an organised fashion as well as through varying degrees of individual efforts. Many Poles offered food to Polish Jews and left food in places Jews would pass on their way to forced labour. Others, directed Jews who managed to escape from the ghettos – to Polish people who could help them. Some sheltered Jews for only one or a few nights, others assumed full responsibility for the Jews' survival, well aware that the Nazis punished those who helped Jews by summary killings. A special role fell to the Polish medical doctors who alone saved thousands of Jews through their subversive practise. For example, Dr. Eugeniusz Łazowski, known as Polish 'Schindler', saved 8,000 Polish Jews from deportation to death camps, by faking an epidemic of typhus in the town of Rozwadów.[31][32]

Free medicine was given out in the Kraków Ghetto by Tadeusz Pankiewicz saving unspecified number of Jews.[33] Rudolf Weigl employed and protected Jews in his Institute in Lwów. His vaccines were smuggled into the local ghetto as well as the ghetto in Warsaw saving countless lives.[34] Dr. Tadeusz Kosibowicz, director of the state hospital in Będzin was sentenced to death for rescuing Jewish fugitives.[35] It is mostly those who took full responsibility who qualify for the title of the Righteous Among the Nations.[36] To date, a total of 6,066 Poles have been officially recognized by Israel as the Polish Righteous among the Nations for their efforts in saving Polish Jews during the Holocaust, making Poland the country with the highest number of Righteous in the world.[37][38]

Statistics

The number of Poles who rescued Jews from the Nazi persecution would be hard to determine in black-and-white terms, and is still the subject of scholarly debate. According to Gunnar S. Paulsson, the number of rescuers that meet Yad Vashem's criteria is perhaps 100,000 and there may have been two or three times as many who offered minor help; the majority "were passively protective."[38] In an article published in the Journal of Genocide Research, Hans G. Furth estimated that there may have been as many as 1,200,000 Polish rescuers.[39] Richard C. Lukas estimated that upwards of 1,000,000 Poles were involved in such rescue efforts,[2] "but some estimates go as high as three million."[2] Lukas also cites Władysław Bartoszewski, a wartime member of Żegota, as having estimated that "at least several hundred thousand Poles ... participated in various ways and forms in the rescue action."[2] Elsewhere, Bartoszewski has estimated that between 1 and 3 percent of the Polish population was actively involved in rescue efforts;[40] Marcin Urynowicz estimates that a minimum of from 500,000 to over a million Poles actively tried to help Jews.[41] The lower number was proposed by Teresa Prekerowa who claimed that between 160,000 and 360,000 Poles assisted in hiding Jews, amounting to between 1% and 2.5% of the 15 million adult Poles she categorized as "those who could offer help." Her estimation counts only those who were involved in hiding Jews directly. It also assumes that each Jew who hid among the non-Jewish populace stayed throughout the war in only one hiding place and as such had only one set of helpers.[42] However, other historians indicate that a much higher number was involved.[43][44] Paulsson wrote that, according to his research, an average Jew in hiding stayed in seven different places throughout the war.[38]

An average Jew who survived in occupied Poland depended on many acts of assistance and tolerance, wrote Paulsson.[38] "Nearly every Jew that was rescued, was rescued by the cooperative efforts of dozen or more people,"[38] as confirmed also by the Polish-Jewish historian Szymon Datner.[46] Paulsson notes that during the six years of wartime and occupation, the average Jew sheltered by the Poles had three or four sets of false documents and faced recognition as a Jew multiple times.[38] Datner explains also that hiding a Jew lasted often for several years thus increasing the risk involved for each Christian family exponentially.[46] Polish-Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor Hanna Krall has identified 45 Poles who helped to shelter her from the Nazis[46] and Władysław Szpilman, the Polish musician of Jewish origin whose wartime experiences were chronicled in his memoir The Pianist and the film of the same title identified 30 Poles who helped him to survive the Holocaust.[47]

Meanwhile, Father John T. Pawlikowski from Chicago, referring to work by other historians, speculated that claims of hundreds of thousands of rescuers struck him as inflated.[48] Likewise, Martin Gilbert has written that under Nazi regime, rescuers were an exception, albeit one that could be found in towns and villages throughout Poland.[49]

There is no official number of how many Polish Jews were hidden by their Christian countrymen during wartime. Lukas estimated that the number of Jews sheltered by Poles at one time might have been "as high as 450,000."[2] However, concealment did not automatically assure complete safety from the Nazis, and the number of Jews in hiding who were caught has been estimated variously from 40,000 to 200,000.[2]

Difficulties

Efforts at rescue were encumbered by several factors. The threat of the death penalty for aiding Jews and limited ability to provide for the escapees were often responsible for the fact that many Poles were unwilling to provide direct help to a person of Jewish origin.[2] This was exacerbated by the fact that the people who were in hiding did not have official ration cards and hence food for them had to be purchased on the black market at high prices.[2][50] According to Emmanuel Ringelblum in most cases the money that Poles accepted from Jews they helped to hide, was taken not out of greed, but out of poverty which Poles had to endure during the German occupation. Israel Gutman has written that the majority of Jews who were sheltered by Poles paid for their own up-keep,[51] but thousands of Polish protectors perished along with the people they were hiding.[52]

There is general consensus among scholars that, unlike in Western Europe, Polish collaboration with the Nazis was insignificant.[2][53][54][55] However, the Nazi terror combined with inadequacy of food rations, as well as German greed, along with the system of corruption as the only "one language the Germans understood well," wrecked traditional values.[56] Poles helping Jews faced unparalleled dangers not only from the German occupiers but also from their own ethnically diverse countrymen including Polish-German Volksdeutsche,[13] and Polish Ukrainians,[57] many of whom were anti-Semitic and morally disoriented by the war.[58] There were people, the so-called szmalcownicy ("shmalts people" from shmalts or szmalec, slang term for money),[59] who blackmailed the hiding Jews and Poles helping them, or who turned the Jews to the Germans for a reward. Outside the cities there were peasants of various ethnic backgrounds looking for Jews hiding in the forests, to demand money from them.[56] There were also Jews turning in other Jews and non-Jewish Poles for profit,[16] or in order to alleviate hunger with the awarded prize.[60] The vast majority of these individuals joined the criminal underworld after the German occupation and were responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of people, both Jews and the Poles who were trying to save them.[61][62][63] The fear of denunciation was ever-present, but often entirely misplaced. There were instances of Polish families sheltering Jews door-to-door and both fearing denunciation unaware of what the other was doing.[64]

According to one reviewer of Paulsson, with regard to the extortionists, "a single hooligan or blackmailer could wreak severe damage on Jews in hiding, but it took the silent passivity of a whole crowd to maintain their cover."[61] He also notes that "hunters" were outnumbered by "helpers" by a ratio of one to 20 or 30.[38] According to Lukas the number of renegades who blackmailed and denounced Jews and their Polish protectors probably did not number more than 1,000 individuals out of the 1,300,000 people living in Warsaw in 1939.[2][65]

Michael C. Steinlauf writes that not only the fear of the death penalty was an obstacle limiting Polish aid to Jews, but also some prewar attitudes towards Jews, which made many individuals uncertain of their neighbors' reaction to their attempts at rescue.[66] Number of authors have noted the negative consequences of the hostility towards Jews by extremists advocating their eventual removal from Poland.[67][68][69][70] Meanwhile, Alina Cala in her study of Jews in Polish folk culture argued also for the persistence of traditional religious antisemitism and anti-Jewish propaganda before and during the war both leading to indifference.[71][72] Steinlauf however notes that despite these uncertainties, Jews were helped by countless thousands of individual Poles throughout the country. He writes that "not the informing or the indifference, but the existence of such individuals is one of the most remarkable features of Polish-Jewish relations during the Holocaust."[66][71] Nechama Tec, who herself survived the war aided by a group of Catholic Poles,[73] noted that Polish rescuers worked within an environment that was hostile to Jews and unfavorable to their protection, in which rescuers feared both the disapproval of their neighbors and reprisals that such disapproval might bring.[74] Tec also noted that Jews, for many complex and practical reasons, were not always prepared to accept assistance that was available to them.[75] Some Jews were pleasantly surprised to have been aided by people whom they thought to have expressed antisemitic attitudes before the invasion of Poland.[38][76]

Former Director of the Department of the Righteous at Yad Vashem, Mordecai Paldiel, wrote that the widespread revulsion among the Polish people at the murders being committed by the Nazis was sometimes accompanied by an alleged feeling of relief at the disappearance of Jews.[77] Israeli historian Joseph Kermish (born 1907) who left Poland in 1950, had claimed at the Yad Vashem conference in 1977, that the Polish researchers overstate the achievements of the Żegota organization (including members of Żegota themselves, along with venerable historians like Prof. Madajczyk), but his assertions are not supported by the listed evidence.[78] Paulsson and Pawlikowski wrote that wartime attitudes among some of the populace were not a major factor impeding the survival of sheltered Jews, or the work of the Żegota organization.[38][76]

The fact that the Polish Jewish community was destroyed during World War II, coupled with stories about Polish collaborators, has contributed, especially among Israelis and American Jews, to a lingering stereotype that the Polish population has been passive in regard to, or even supportive of, Jewish suffering.[38] However, modern scholarship has not validated the claim that Polish antisemitism was irredeemable or different from contemporary Western antisemitism; it has also found that such claims are among the stereotypes that comprise anti-Polonism.[79] The presenting of selective evidence in support of preconceived notions have led some popular press to draw overly simplistic and often misleading conclusions regarding the role played by Poles at the time of the Holocaust.[38][79]

Punishment for aiding the Jews

In an attempt to discourage Poles from helping the Jews and to destroy any efforts of the resistance, the Germans applied a ruthless retaliation policy. On 10 November 1941, the death penalty was introduced by Hans Frank, governor of the General Government, to apply to Poles who helped Jews "in any way: by taking them in for the night, giving them a lift in a vehicle of any kind" or "feed[ing] runaway Jews or sell[ing] them foodstuffs." The law was made public by posters distributed in all cities and towns, to instill fear.[80]

The imposition of the death penalty for Poles aiding Jews was unique to Poland among all German occupied countries, and was a result of the conspicuous and spontaneous nature of such an aid.[81] For example, the Ulma family (father, mother and six children) of the village of Markowa near Łańcut – where many families concealed their Jewish neighbors – were executed jointly by the Nazis with the eight Jews they hid.[82] The entire Wołyniec family in Romaszkańce was massacred for sheltering three Jewish refugees from a ghetto. In Maciuńce, for hiding Jews, the Germans shot eight members of Józef Borowski's family along with him and four guests who happened to be there.[83] Nazi death squads carried out mass executions of the entire villages that were discovered to be aiding Jews on a communal level.[37][84] In the villages of Białka near Parczew and Sterdyń near Sokołów Podlaski, 150 villagers were massacred for sheltering Jews.[85]

In November 1942, the Ukrainian SS squad executed 20 villagers from Berecz in Wołyń Voivodeship for giving aid to Jewish escapees from the ghetto in Povorsk.[86] According to Peter Jaroszczak "Michał Kruk and several other people in Przemyśl were executed on September 6, 1943 (pictured) for the assistance they had rendered to the Jews. Altogether, in the town and its environs 415 Jews (including 60 children) were saved, in return for which the Germans killed 568 people of Polish nationality."[87] Several hundred Poles were massacred with their priest, Adam Sztark, in Słonim on 18 December 1942, for sheltering Jewish refugees of the Słonim Ghetto in a Catholic church. In Huta Stara near Buczacz, Polish Christians and the Jewish countrymen they protected were herded into a church by the Nazis and burned alive on 4 March 1944.[88] In the years 1942–1944 about 200 peasants were shot dead and burned alive as punishment in the Kielce region alone.[89]

Entire communities that helped to shelter Jews were annihilated, such as the now-extinct village of Huta Werchobuska near Złoczów, Zahorze near Łachwa,[90] Huta Pieniacka near Brody[91] or Stara Huta near Szumsk.[92]

Additionally, after the end of the war Poles who saved Jews during the Nazi occupation very often became the victims of repression at the hands of the Communist security apparatus, due to their instinctive devotion to social justice which they saw as being abused by the government.[89]

Jews in Polish villages

A number of Polish villages in their entirety provided shelter from Nazi apprehension, offering protection for their Jewish neighbors as well as the aid for refugees from other villages and escapees from the ghettos.[93] Postwar research has confirmed that communal protection occurred in Głuchów near Łańcut with everyone engaged,[94] as well as in the villages of Główne, Ozorków, Borkowo near Sierpc, Dąbrowica near Ulanów, in Głupianka near Otwock,[95] and Teresin near Chełm.[96] In Cisie near Warsaw, 25 Poles were caught hiding Jews; all were killed and the village was burned to the ground as punishment.[97][98]

The forms of protection varied from village to village. In Gołąbki, the farm of Jerzy and Irena Krępeć provided a hiding place for as many as 30 Jews; years after the war, the couple's son recalled in an interview with the Montreal Gazette that their actions were "an open secret in the village [that] everyone knew they had to keep quiet" and that the other villagers helped, "if only to provide a meal."[99] Another farm couple, Alfreda and Bolesław Pietraszek, provided shelter for Jewish families consisting of 18 people in Ceranów near Sokołów Podlaski, and their neighbors brought food to those being rescued.[100]

Two decades after the end of the war, a Jewish partisan named Gustaw Alef-Bolkowiak identified the following villages in the Parczew-Ostrów Lubelski area where "almost the entire population" assisted Jews: Rudka, Jedlanka, Makoszka, Tyśmienica, and Bójki.[93] Historians have documented that a dozen villagers of Mętów near Głusk outside Lublin sheltered Polish Jews.[101] In some well-confirmed cases, Polish Jews who were hidden, were circulated between homes in the village. Farmers in Zdziebórz near Wyszków sheltered two Jewish men by taking turns. Both of them later joined the Polish underground Home Army.[102] The entire village of Mulawicze near Bielsk Podlaski took responsibility for the survival of an orphaned nine-year-old Jewish boy.[103] Different families took turns hiding a Jewish girl at various homes in Wola Przybysławska near Lublin,[104] and around Jabłoń near Parczew many Polish Jews successfully sought refuge.[105]

Impoverished Polish Jews, unable to offer any money in return, were nonetheless provided with food, clothing, shelter and money by some small communities;[5] historians have confirmed this took place in the villages of Czajków near Staszów[106] as well as several villages near Łowicz, in Korzeniówka near Grójec, near Żyrardów, in Łaskarzew, and across Kielce Voivodship.[107]

In tiny villages where there was no permanent Nazi military presence, such as Dąbrowa Rzeczycka, Kępa Rzeczycka and Wola Rzeczycka near Stalowa Wola, some Jews were able to openly participate in the lives of their communities. Olga Lilien, recalling her wartime experience in the 2000 book To Save a Life: Stories of Holocaust Rescue, was sheltered by a Polish family in a village near Tarnobrzeg, where she survived the war despite the posting of a 200 deutsche mark reward by the Nazi occupiers for information on Jews in hiding.[108] Chava Grinberg-Brown from Gmina Wiskitki recalled in a postwar interview that some farmers used the threat of violence against a fellow villager who intimated the desire to betray her safety.[109] Polish-born Israeli writer and Holocaust survivor Natan Gross, in his 2001 book Who Are You, Mr. Grymek?, told of a village near Warsaw where a local Nazi collaborator was forced to flee when it became known he reported the location of a hidden Jew.[110]

Nonetheless there were cases where Poles who saved Jews were met with a different response after the war. Antonina Wyrzykowska from Janczewko village near Jedwabne managed to successfully shelter seven Jews for twenty-six months from November 1942 until liberation. Some time earlier, during the Jedwabne pogrom close by, a minimum of 300 Polish Jews were burned alive in a barn set on fire by a group of Polish men under the German command.[111] Among the Jews rescued by Wyrzykowska was Szmuel Wasersztajn who, without seeing anything that happened, later falsely accused many innocent Poles of the crime.[112] Wyrzykowska was honored as Righteous among the Nations for her heroism, but left her hometown after liberation for fear of retribution.[113][114][115][116][117]

Jews in Polish cities

In Poland's cities and larger towns, the Nazi occupiers created ghettos that were designed to imprison the local Jewish populations. The food rations allocated by the Germans to the ghettos condemned their inhabitants to starvation.[118] Smuggling of food into the ghettos and smuggling of goods out of the ghettos, organized by Jews and Poles, was the only means of subsistence of the Jewish population in the ghettos. The price difference between the Aryan and Jewish sides was large, reaching as much as 100%, but the penalty for aiding Jews was death. Hundreds of Polish and Jewish smugglers would come in and out the ghettos, usually at night or at dawn, through openings in the walls, underground tunnels and sewers or through the guardposts by paying bribes.[119]

The Polish Underground urged the Poles to support smuggling.[119] The punishment for smuggling was death, carried out on the spot.[119] Among the Jewish smuggler victims were scores of Jewish children aged five or six, whom the German shot at the ghetto exits and near the walls. While communal rescue was impossible under these circumstances, many Polish Christians concealed their Jewish neighbors. For example, Zofia Baniecka and her mother rescued over 50 Jews in their home between 1941 and 1944. Paulsson, in his research on the Jews of Warsaw, documented that Warsaw's Polish residents managed to support and conceal the same percentage of Jews as did residents in other European cities under Nazi occupation.[61]

Ten percent of Warsaw's Polish population was actively engaged in sheltering their Jewish neighbors.[38] It is estimated that the number of Jews living in hiding on the Aryan side of the capital city in 1944 was at least 15,000 to 30,000 and relied on the network of 50,000–60,000 Poles who provided shelter, and about half as many assisting in other ways.[38]

Organizations dedicated to saving the Jews

Several organizations dedicated to saving Jews were created and run by Catholic Poles with the help of the Polish Jewish underground.[120] Among those, Żegota, the Council to Aid Jews, was the most prominent.[76] It was unique not only in Poland, but in all of Nazi-occupied Europe, as there was no other organization dedicated solely to that goal.[76][121] Żegota concentrated its efforts on saving Jewish children toward whom the Germans were especially cruel.[76] Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998) gives several wide-range estimates of a number of survivors including those who might have received assistance from Żegota in some form including financial, legal, medical, child care, and other help in times of trouble.[122] The subject is shrouded in controversy according to Szymon Datner, but in Lukas' estimate about half of those who survived within the changing borders of Poland were helped by Żegota. The number of Jews receiving assistance who did not survive the Holocaust is not known.[122]

Perhaps the most famous member of Żegota was Irena Sendler, who managed to successfully smuggle 2,500 Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto.[123] Żegota was granted over 5 million dollars or nearly 29 million zł by the government-in-exile (see below), for the relief payments to Jewish families in Poland.[124] Besides Żegota, there were smaller organizations such as KZ-LNPŻ, ZSP, SOS and others (along the Polish Red Cross), whose action agendas included help to the Jews. Some were associated with Żegota.[125]

Jews and the Church

The Roman Catholic Church in Poland provided many persecuted Jews with food and shelter during the war,[125] even though monasteries gave no immunity to Polish priests and monks against the death penalty.[126] Nearly every Catholic institution in Poland looked after a few Jews, usually children with forged Christian birth certificates and an assumed or vague identity.[38] In particular, convents of Catholic nuns in Poland (see Sister Bertranda), played a major role in the effort to rescue and shelter Polish Jews, with the Franciscan Sisters credited with the largest number of Jewish children saved.[127][128] Two thirds of all nunneries in Poland took part in the rescue, in all likelihood with the support and encouragement of the church hierarchy.[129] These efforts were supported by local Polish bishops and the Vatican itself.[128] The convent leaders never disclosed the exact number of children saved in their institutions, and for security reasons the rescued children were never registered. Jewish institutions have no statistics that could clarify the matter.[126] Systematic recording of testimonies did not begin until the early 1970s.[126] In the villages of Ożarów, Ignaców, Szymanów, and Grodzisko near Leżajsk, the Jewish children were cared for by Catholic convents and by the surrounding communities. In these villages, Christian parents did not remove their children from schools where Jewish children were in attendance.[130]

Irena Sendler head of children's section Żegota (the Council to Aid Jews) organisation cooperated very closely in saving Jewish children from the Warsaw Ghetto with social worker and Catholic nun, mother provincial of Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary - Matylda Getter. The children were placed with Polish families, the Warsaw orphanage of the Sisters of the Family of Mary, or Roman Catholic convents such as the Little Sister Servants of the Blessed Virgin Mary Conceived Immaculate at Turkowice and Chotomów.[131] Sister Matylda Getter rescued between 250 and 550 Jewish children in different education and care facilities for children in Anin, Białołęka, Chotomów, Międzylesie, Płudy, Sejny, Vilnius and others.[132] Getter's convent was located at the entrance to the Warsaw Ghetto. When the Nazis commenced the clearing of the Ghetto in 1941, Getter took in many orphans and dispersed them among Family of Mary homes. As the Nazis began sending orphans to the gas chambers, Getter issued fake baptismal certificates, providing the children with false identities. The sisters lived in daily fear of the Germans. Michael Phayer credits Getter and the Family of Mary with rescuing more than 750 Jews.[40]

Polish Catholic Church had issued false documents to about 50,000 Jews confirming their Christian origin. Every hiding Jew had to have such a certificate to hide in plain sight, which was possible only thanks to the involvement of the Catholic clergy in saving Jews. Under the 1929 concordat, Catholic parishes in Poland performed the functions of today's Civil Registry Offices. The false documents they issued included names confirmed by the parish registers.[133] They were meant to protect the hidden Jews from being exposed, and to prove their non-Jewish identities. Presently, around 600 biographies of diocesan priests, who saved Jews, have been collected as part of the project "Priest for Jews". Historians also found that Jews were hidden in more than 70 men's monasteries in Poland. For this activity, the Righteous Among the Nations awards were bestowed upon several dozen Polish Catholic clergy.[133][134]

Historians have shown that in numerous villages, Jewish families survived the Holocaust by living under assumed identities as Christians with full knowledge of the local inhabitants who did not betray their identities. This has been confirmed in the settlements of Bielsko (Upper Silesia), in Dziurków near Radom, in Olsztyn Village near Częstochowa, in Korzeniówka near Grójec, in Łaskarzew, Sobolew, and Wilga triangle, and in several villages near Łowicz.[135]

Some officials in the senior Polish priesthood maintained the same theological attitude of hostility toward the Jews which was known from before the invasion of Poland.[38][136] After the war ended, some convents were unwilling to return Jewish children to postwar institutions that asked for them, and at times refused to disclose the adoptive parents' identities, forcing government agencies and courts to intervene.[137]

Jews and the Polish government

Lack of international effort to aid Jews resulted in political uproar on the part of the Polish government in exile residing in Great Britain. The government often publicly expressed outrage at German mass murders of Jews. In 1942, Directorate of Civil Resistance, part of the Polish Underground State, issued a following declaration based on reports by Polish underground.[138]

For nearly a year now, in addition to the tragedy of the Polish people, which is being slaughtered by the enemy, our country has been the scene of a terrible, planned massacre of the Jews. This mass murder has no parallel in the annals of mankind; compared to it, the most infamous atrocities known to history pale into insignificance. Unable to act against this situation, we, in the name of the entire Polish people, protest the crime being perpetrated against the Jews; all political and public organizations join in this protest.[138]

Polish government was the first to inform the Western Allies about the Holocaust, although early reports were often met with disbelief even by Jewish leaders themselves; then, for much longer, by Western powers.[121][122][125][139][140][141]

Witold Pilecki was member of Polish Armia Krajowa resistance, and the only person who volunteered to be imprisoned in Auschwitz. As agent of underground intelligence he begun sending numerous reports about camp and genocide to Polish resistance headquarters in Warsaw through the resistance network he organized in Auschwitz. In March 1941, Pilecki's reports were being forwarded via the Polish resistance to the British government in London but the British authorities refused AK reports on atrocities as being gross exaggerations and propaganda of the Polish government.

Similarly, Jan Karski, who had been serving as a courier between the Polish underground and the Polish government in exile, was smuggled into the Warsaw Ghetto and reported to the Polish, British and American governments on the situation of Jews in Poland.[142] In 1942 Karski reported to the Polish, British and US governments on the situation in Poland, especially the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto and the Holocaust of the Jews. He met with Polish politicians in exile including the prime minister, as well as members of political parties such as the Polish Socialist Party, National Party, Labor Party, People's Party, Jewish Bund and Poalei Zion. He also spoke to Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, and included a detailed statement on what he had seen in Warsaw and Bełżec. In 1943 in London he met the then much known journalist Arthur Koestler. He then traveled to the United States and reported to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In July 1943, Jan Karski again personally reported to Roosevelt about the plight of Polish Jews, but the president "interrupted and asked the Polish emissary about the situation of... horses" in Poland.[143][144] He also met with many other government and civic leaders in the United States, including Felix Frankfurter, Cordell Hull, William Joseph Donovan, and Stephen Wise. Karski also presented his report to media, bishops of various denominations (including Cardinal Samuel Stritch), members of the Hollywood film industry and artists, but without success. Many of those he spoke to did not believe him and again supposed that his testimony was much exaggerated or was propaganda from the Polish government in exile.

The supreme political body of the underground government within Poland was the Delegatura. There were no Jewish representatives in it.[145] Delegatura financed and sponsored Żegota, the organization for help to the Polish Jews – run jointly by Jews and non-Jews.[146] Since 1942 Żegota was granted by Delegatura nearly 29 million zlotys (over $5 million; or, 13.56 times as much,[147] in today's funds) for the relief payments to thousands of extended Jewish families in Poland.[148] The government-in-exile also provided special assistance including funds, arms and other supplies to Jewish resistance organizations (like ŻOB and ŻZW), particularly from 1942 onwards.[140] The interim government transmitted messages to the West from the Jewish underground, and gave support to their requests for retaliation on German targets if the atrocities are not stopped – a request that was dismissed by the Allied governments.[140] The Polish government also tried, without much success, to increase the chances of Polish refugees finding a safe haven in neutral countries and to prevent deportations of escaping Jews back to Nazi-occupied Poland.[140]

Polish Delegate of the Government in Exile residing in Hungary, diplomat Henryk Sławik known as the Polish Wallenberg,[149] helped rescue over 30,000 refugees including 5,000 Polish Jews in Budapest, by giving them false Polish passports as Christians.[150] He founded an orphanage for Jewish children officially named School for Children of Polish Officers in Vác.[151][152]

With two members on the National Council, Polish Jews were sufficiently represented in the government in exile.[140] Also, in 1943 a Jewish affairs section of the Underground State was set up by the Government Delegation for Poland; it was headed by Witold Bieńkowski and Władysław Bartoszewski.[138] Its purpose was to organize efforts concerning the Polish Jewish population, to coordinate with Zegota, and to prepare documentation about the fate of the Jews for the government in London.[138] Regrettably, the great number of Polish Jews had been killed already even before the Government-in-exile fully realized the totality of the Final Solution.[140] According to David Engel and Dariusz Stola, the government-in-exile concerned itself with the fate of Polish people in general, the re-recreation of the independent Polish state, and with establishing itself as an equal partner amongst the Allied forces.[140][141][153] On top of its relative weakness, the government in exile was subject to the scrutiny of the West, in particular, American and British Jews reluctant to criticize their own governments for inaction in regard to saving their fellow Jews.[140][154]

The Polish government and its underground representatives at home issued declarations that people acting against the Jews (blackmailers and others) would be punished by death. General Władysław Sikorski, the Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, signed a decree calling upon the Polish population to extend aid to the persecuted Jews; including the following stern warning.[155]

Any direct and indirect complicity in the German criminal actions is the most serious offence against Poland. Any Pole who collaborates in their acts of murder, whether by extortion, informing on Jews, or by exploiting their terrible plight or participating in acts of robbery, is committing a major crime against the laws of the Polish Republic. — Warsaw, May 1943 [155]

According to Michael C. Steinlauf, before the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943, Sikorski's appeals to Poles to help Jews accompanied his communiques only on rare occasions.[156] Steinlauf points out that in one speech made in London, he was promising equal rights for Jews after the war, but the promise was omitted from the printed version of the speech for no reason.[156] According to David Engel, the loyalty of Polish Jews to Poland and Polish interests was held in doubt by some members of the exiled government,[141][153] leading to political tensions.[157] For example, the Jewish Agency refused to give support to Polish demand for the return of Lwów and Wilno to Poland.[158] Overall, as Stola notes, Polish government was just as unprepared to deal with the Holocaust as were the other Allied governments, and that the government's hesitancy in appeals to the general population to aid the Jews diminished only after reports of the Holocaust became more wide spread.[140]

Szmul Zygielbojm, a Jewish member of the National Council of the Polish government in exile, committed suicide in May 1943, in London, in protest against the indifference of the Allied governments toward the destruction of the Jewish people, and the failure of the Polish government to rouse public opinion commensurate with the scale of the tragedy befalling Polish Jews.[159]

Poland, with its unique underground state, was the only country in occupied Europe to have an extensive, underground justice system.[161] These clandestine courts operated with attention to due process (obviously limited by circumstances) and as a result it could take months to get a death sentence passed, much as in regular judicial systems.[161] However, Prekerowa notes that the death sentences by non-military courts only began to be issued in September 1943, which meant that blackmailers were able to operate for some time already since the first Nazi anti-Jewish measures of 1940.[162] Overall, it took the Polish underground until late 1942 to legislate and organize non-military courts which were authorized to pass death sentences for civilian crimes, such as non-treasonous collaboration, extortion and blackmail.[161] According to Joseph Kermish from Israel, among the thousands of collaborators sentenced to death by the Special Courts and executed by the Polish resistance fighters who risked death carrying out these verdicts,[162] few were explicitly blackmailers or informers who had persecuted Jews. This, according to Kermish, led to increasing boldness of some of the blackmailers in their criminal activities.[78] Marek Jan Chodakiewicz writes that a number of Polish Jews were executed for denouncing other Jews. He notes that since Nazi informers often denounced members of the underground as well as Jews in hiding, the charge of collaboration was a general one and sentences passed were for cumulative crimes.[163]

The Home Army units under the command of officers from left-wing Sanacja, the PPS as well as the centrist Democratic Party welcomed Jewish fighters to serve with Poles without problems stemming from their ethnic identity. As noted by Joshua D. Zimmerman, many negative stereotypes about the Home Army among the Jews came from reading postwar literature on the subject, and not from personal experience.[164] In spite of Polish Jewish representation in the London-based government in exile, some rightist units of the Armia Krajowa – as noted by Joanna B. Michlic – exhibited ethno-nationalism that excluded Jews. Similarly, some members of the Delegate's Bureau saw Jews and ethnic Poles as separate entities.[165] Historian Israel Gutman has noted that AK leader Stefan Rowecki advocated the abandonment of the long-range considerations of the underground and the launch of an all-out uprising should the Germans undertake a campaign of extermination against ethnic Poles, but that no such plan existed while the extermination of Jewish Polish citizens was under way.[166] On the other hand, not only the pre-war Polish government armed and trained Jewish paramilitary groups such as Lehi but also – while in exile – accepted thousands of Polish Jewish fighters into Anders Army including leaders such as Menachem Begin. The policy of support continued throughout the war with the Jewish Combat Organization and the Jewish Military Union forming an integral part of the Polish resistance.[167]

Towns and villages

Below is a partial list of Polish communities that collectively rescued Jews during the Jewish Holocaust. The spelling of some towns, villages, and counties has been revised in accord with current data. Occasionally the links lead to disambiguation pages listing villages of the same name in the same area of prewar or postwar Poland.[168]

For list of towns, villages, and their locations in alphabetical order, please use the table-sort buttons.

- † A cross marks the Polish villages razed in various pacification operations during World War II, and no longer existing in that form. For more information see: Pacifications of villages in German-occupied Poland or the aftermath of the Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia and the Zamość Uprising among others.

See also

- List of individuals and groups assisting Jews during the Holocaust

- Rescue of Jews by Catholics during the Holocaust

- Irena's Vow, stage play recounting the story of Irena Gut

- Kastner's Train of 1,684 Jews freed from Nazi-controlled Hungary

- Schindler's List biographical drama film about Oskar Schindler

Notes

- ^ a b Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority, Righteous Among the Nations - per Country & Ethnic Origin January 1, 2011. Statistics

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lukas, Richard C. (1989). Out of the Inferno: Poles Remember the Holocaust. University Press of Kentucky. p. 13. ISBN 0813116929.

The estimates of Jewish survivors in Poland... do not accurately reflect the extent of the Poles' enormous sacrifices on behalf of the Jews because, at various times during the occupation, there were more Jews in hiding than in the end survived.

- ^ "About the Righteous: Statistics". The Righteous Among The Nations. Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. 1 January 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Epstein, Catherine (2015). Nazi Germany: Confronting the Myths. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 172–173. ISBN 1118294793. Although the refusal to bomb Auschwitz seems a case of moral indifference, it was, in fact, reasoned strategy. – via Google Books. See also: Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (10 December 1942), The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland. Note to the Governments of the United Nations.

- ^ a b Piotrowski (1998), p. 119, chpt. Assistance.

- ^ Chaim Chefer (1996). "Righteous of the World: Polish citizens killed while helping Jews During the Holocaust". Those That Helped. The HolocaustForgotten.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ London Nakl. Stowarzyszenia Prawników Polskich w Zjednoczonym Królestwie [1941], Polska w liczbach. Poland in numbers. Zebrali i opracowali Jan Jankowski i Antoni Serafinski. Przedmowa zaopatrzyl Stanislaw Szurlej.

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt (2011), Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950). Polish Academy of Sciences; Stanisław Leszczycki Institute, Monographies; 12, pp. 25–29; via Internet Archive.

- ^ From Ringelblum’s Diary: "As the Ghetto is Sealed Off, Jews and Poles Remain in Contact." June 1942.

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, "POLES: VICTIMS OF THE NAZI ERA" Washington D.C.

- ^ Hitler's War; Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe. Warsaw: Polonia Publishing House. 1961. pp. 7–33, 164–178 – via Internet Archive, 28 December 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Marta Żyńska (2003). "Prawda poświadczona życiem (biography of Sister Marta Wołowska)". 30. Tygodnik Katolicki 'Niedziela'.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Emanuel Ringelblum, Joseph Kermish, Shmuel Krakowski, Polish-Jewish relations during the Second World War. Page 226. Quote from chapter "The Idealists": "Informing and denunciation flourish throughout the country, thanks largely to the Volksdeutsche. Arrests and round-ups at every step and constant searches..."

- ^ Matthew J. Gibney, Randall Hansen, Immigration and Asylum, page 204

- ^ Wacław Zajączkowski (June 1988). Christian Martyrs of Charity (PDF). Washington, D.C.: S.M. Kolbe Foundation. pp. 152–178 (1–14 of 25 in current document). ISBN 0945281005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2015.

In Grzegorzówka, and in Hadle Szklarskie (Przeworsk County, Rzeszów Voivodeship), military police extracted from two Jewish women the names of Christian Poles helping them and other Jews – 11 Polish men were murdered. In Korniaktów forest (Łańcut County, Rzeszów Voivodeship) a Jewish woman caught in a bunker revealed the whereabouts of the Catholic family who fed her – the whole Polish family were murdered. In Jeziorko, Łowicz County (Warsaw Voivodeship), a Jewish man betrayed all Polish rescuers known to him – 13 Catholics were murdered by the German military police. In Lipowiec Duży (Biłgoraj County, Lublin Voivodeship), a captured Jew led the Germans to his saviors – 5 Catholics were murdered including a 6-year-old child and their farm was burned. There were other similar cases.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Paul, Mark (September 2015). "Patterns of Cooperation, Collaboration and Betrayal: Jews, Germans and Poles in Occupied Poland during World War II" (PDF). Glaukopis. Foreign language studies. 159/344 in PDF. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

Testimony of Anzel Daches, Majer Gdański, Laja Goldman, Mojżesz Klajman, Chana Kohn, Jakub Libman, and Izrael Szerman, dated October 13, 1947; Jewish Historical Institute Archive, record group 301, number 2932.

- ^ a b Richard C. Lukas (1989). Out of the inferno: Poles remember ... University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813116929 – via Google Books.

- ^ Christopher R. Browning, Jurgen Matthaus, The Origins of the Final Solution, page 262 Publisher University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8032-5979-4

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2017), Holocaust by Bullets

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 209, 'Pogroms involving murder.'

- ^ Ronald Headland (1992), Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, pp. 125–126. ISBN 0-8386-3418-4.

- ^ Niwiński, Piotr (2011). Ponary : the Place of "Human Slaughter". Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu; Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, Departament Współpracy z Polonią. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Alfred J. Rieber. "Civil Wars in the Soviet Union" (PDF). Project Muse: 145–147.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Symposium Presentations (September 2005). "The Holocaust and [German] Colonialism in Ukraine: A Case Study" (PDF). The Holocaust in the Soviet Union. The Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 15, 18–19, 20 in current document of 1/154. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2012 – via direct download 1.63 MB.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ I.K. Patrylyak (2004). "The Military Activities of the OUN (B), 1940–1942" [Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940–1942 роках] (PDF). Kiev: Shevchenko University; Institute of History of Ukraine. 522–524 (4–6/45 in PDF).

- ^ Іван Качановський (30 March 2013). "Contemporary politics of OUN (b) memory in Volhynia, and the Nazi massacres" [Сучасна політика пам'яті на Волині щодо ОУН(б) та нацистських масових вбивств]. Україна модерна.

- ^ Bubnys, Arūnas (2004). "The Holocaust in Lithuania: An Outline of the Major Stages and Results". The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews. Rodopi. pp. 209–210. ISBN 90-420-0850-4.

- ^ Paweł Machcewicz, "Płomienie nienawiści", Polityka 43 (2373), 26 October 2002, p. 71-73. The Findings. Archived 10 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael C. Steinlauf. Bondage to the Dead. Syracuse University Press, p. 30.

- ^ Waclaw Szybalski, McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, University of Wisconsin, Madison WI (2003). "The genius of Rudolf Stefan Weigl (1883-1957), a Lvovian microbe hunter and breeder. In Memoriam". International Weigl Conference (Microorganisms in Pathogenesis and their Drug Resistance - Programme and Abstracts; R. Stoika et al., Eds.) 11–14 Sep 2003, pp. 10 - 31. Archived from the original on 15 March 2006.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Art Golab, "Chicago's 'Schindler' who saved 8,000 Jews". Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Chicago Sun-Times, 20 December 2006. - ^ Andrzej Pityñski, Stalowa Wola Museum, Short biography of Eugeniusz Łazowski. Archived 11 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine (Polish)

- ^ "Museum of National Remembrance at "Under the Eagle Pharmacy"". Krakow-info.com. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Halina Szymanska Ogrodzinska, "Her Story". Recollections

- ^ "Dr. Tadeusz Kosibowicz. Sprawiedliwy wśród Narodów Świata - tytuł przyznany: 20 marca 2006". Historia pomocy. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Krakowski, Shmuel. "Difficulties in Rescue Attempts in Occupied Poland" (PDF). Yad Vashem Archives.

- ^ a b "Righteous Among the Nations by country". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gunnar S. Paulsson, “The Rescue of Jews by Non-Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland,” published in The Journal of Holocaust Education, volume 7, nos. 1 & 2 (summer/autumn 1998): pp.19–44.

- ^ Hans G. Furth, One million Polish rescuers of hunted Jews?. Journal of Genocide Research, Jun99, Vol. 1 Issue 2, p227, 6p; (AN 6025705)

- ^ a b Michael Phayer (2000), The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930-1965. Indiana University Press. Pages 113, 117, 250.

- ^ Marcin Urynowicz, "Organized and individual Polish aid for the Jewish population exterminated by the German invader during the Second World War" as cited by Institute of National Remembrance. The Life for a Life Project: Remembrance of Poles who gave their lives to save Jews

- ^ Prekerowa, Teresa (1989) [1987]. Polonsky, Antony (ed.). The Just and the Passive. Routledge. pp. 72–74.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman. Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath Rutgers University Press, 2003.

- ^ Turowicz, Jerzy (1989). Polonsky, Antony (ed.). Polish reasons and Jewish reasons. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 1134952104.

Note 2: Teresa Prekerowa estimated that approximately 1–2.5 per cent of Poles (between 160,000 and 360,000) were actively engaged in helping Jews to survive.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Urząd Miasta Nowego Sącza (2016). "Sądeczanie w telewizji: Sprawiedliwy Artur Król". Nowy Sącz: Oficjalna strona miasta. Komunikaty Biura Prasowego.

- ^ a b c Piotrowski (1998), p. 22, chpt. Nazi Terror.

- ^ Knade, Tadeusz (12 October 2002). "Człowiek musiał być silny" [The man had to be strong]. Rzeczpospolita. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ John T. Pawlikowski. "Polish Catholics and the Jews during the Holocaust" in: Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, Rutgers University Press, 2003. Page 110

- ^ Martin Gilbert. The Righteous: The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust Macmillan, 2003. pp 102-103.

- ^ Ringelblum, "Polish-Jewish Relations", pg. 226.

- ^ Martin Gilbert. The Righteous: The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust. Macmillan, 2003. p146.

- ^ Lukas, Richard C. (1994). Did the Children Cry? Hitler's War Against Jewish and Polish Children, 1939-1945. Hippocrene Books. pp. 180–189. ISBN 0-7818-0242-3.

- ^ Carla Tonini, The Polish underground press and the issue of collaboration with the Nazi occupiers, 1939–1944, European Review of History: Revue Europeenne d'Histoire, Volume 15, Issue 2 April 2008, pages 193 - 205

- ^ John Connelly, Why the Poles Collaborated so Little: And Why That Is No Reason for Nationalist Hubris. Slavic Review, Vol. 64, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 771–781. In response to article by: Klaus-Peter Friedrich, Collaboration in a "Land without a Quisling": Patterns of Cooperation with the Nazi German Occupation Regime in Poland during World War II. Slavic Review, ibidem.

- ^ John Connelly, Why the Poles Collaborated so Little: And Why That Is No Reason for Nationalist Hubris, Slavic Review, Vol. 64, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 771-781, JSTOR

- ^ a b David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzveig, The world reacts to the Holocaust. Published by JHU Press; pages 81-101, 106.

- ^ Wiktoria Śliwowska, Jakub Gutenbaum, The Last Eyewitnesses, page 187-188 Northwestern Univ Press

- ^ "Nazi German Camps on Polish Soil During World War II". Msz.gov.pl. 14 June 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ "Yad Vashem Holocaust documents part 2, #157". .yadvashem.org. 16 February 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 66, chpt. German Occupation.

- ^ a b c Unveiling the Secret City H-Net Review: John Radzilowski

- ^ Robert Szuchta. Review of Jan Grabowski, "Ja tego Żyda znam! Szantażowanie Żydów w Warszawie, 1939-1943". Zydzi w Polsce

- ^ Robert Szuchta (22 September 2008), "Śmierć dla szmalcowników." Rzeczpospolita.

- ^ Paul, Mark (2015). Patterns of Cooperation, Collaboration and Betrayal: Jews, Germans and Poles in Occupied Poland during World War II (PDF). Glaukopis. page 15 of 344 in current document. ISSN 1730-3419.

- ^ Template:En icon "Demographic Yearbooks of Poland 1939–1979, 1980-1994". www.stat.gov.pl. Central Statistical Office of Poland. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Michael C. Steinlauf. Bondage to the Dead. Syracuse University Press, pp. 41-42.

- ^ Cesarani & Kavanaugh (2004), pp. 41ff, attitudes.

- ^ Israel Gutman. The Jews of Warsaw, 1939-1943. Indiana University Press, 1982. Pages 27ff.

- ^ Antony Polonsky. "Beyond Condemnation, Apologetics and Apologies: On the Complexity of Polish Behavior Towards the Jews During the Second World War." In: Jonathan Frankel, ed. Studies in Contemporary Jewry 13. (1997): 190-224.

- ^ Jan T. Gross. A Tangled Web: Confronting Stereotypes Concerning Relations between Poles, Germans, Jews, and Communists. In: István Deák, Jan Tomasz Gross, Tony Judt. The Politics of Retribution in Europe: World War II and Its Aftermath. Princeton University Press, 2000. P. 84ff

- ^ a b Joshua D. Zimmerman. Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. Rutgers University Press, 2003.

- ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman. Review of Aliana Cala, The Image of the Jew in Polish Folk Culture. In: Jonathan Frankel, ed. Jews and Gender: The Challenge to Hierarchy. Oxford University Press US, 2000.

- ^ "Holocaust survivor Dr. Nechama Tec to address SRU community at remembrance". Sru.edu. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nechama Tec. When Light Pierced the Darkness: Christian Rescue of Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland. Oxford University Press US, 1987.

- ^ Nechama Tec. When Light Pierced the Darkness: Christian Rescue of Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland. Oxford University Press US, 1987.

- ^ a b c d e John T. Pawlikowski, Polish Catholics and the Jews during the Holocaust, in, Google Print, p. 113 in Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, Rutgers University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8135-3158-6

- ^ Mordecai Paldiel. The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust. KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 1993.

- ^ a b Kermish (1977), pp. 14–17, 30, 32: Kermish falsely asserts that the relief payments amounted to 50,000 zł per month (page 4), which is contradicted by the Żegota reports digitized by the Ghetto Fighters House Archives in Jerusalem (Catalog No. 6159) which prove that the Żegota branch in Kraków alone (just one branch) received one million Polish złoty in July 1943. The annual report from December 1944 (paragraph 3) states: "at the end of July an authorization was received from the Warsaw branch confirming the transfer of one million zł to the Krakow branch for distribution to welfare support cases and to the Plaszow, Mielec, Wieliczka, and Stalowa Wola camps - in all, for some 22,000 Jews." According to Polonsky (2004), Żegota was granted 29 million zł by the government-in-exile for the relief payments to Jewish families.

- ^ a b Robert D. Cherry, Annamaria Orla-Bukowska, Rethinking Poles and Jews, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, ISBN 0-7425-4666-7, Google Print, p.25

- ^ Mordecai Paldiel, The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews, page 184. Published by KTAV Publishing House Inc.

- ^ Richard C. Lukas (1989), Out of the Inferno, p. 13; [also in:] Richard C. Lukas (1986), The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles Under German Occupation, 1939-1944. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1566-3.

- ^ The Righteous and their world. Markowa through the lens of Józef Ulma, by Mateusz Szpytma, Institute of National Remembrance

- ^ Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, The Last Rising in the Eastern Borderlands: The Ejszyszki Epilogue in its Historical Context

- ^ Robert D. Cherry, Annamaria Orla-Bukowska, Rethinking Poles and Jews: Troubled Past, Brighter Future, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, ISBN 0-7425-4666-7, Google Print, p.5

- ^ Zajączkowski (1988), Martyrs of Charity. Part One, pp. 123–124, 228; [quoted in:] Paul (2010), p. 261, Wartime Rescue, ibidem. harvp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPaul2010 (help)

- ^ a b Władysław Siemaszko and Ewa Siemaszko, Ludobójstwo dokonane przez nacjonalistów ukraińskich na ludności polskiej Wołynia, 1939–1945, Warsaw: Von Borowiecky, 2000, vol. 1, p. 363. Template:Pl icon

- ^ Leszek M. Włodek, historian (2002). "Zagłada Żydów przemyskich (The destruction of Przemyśl Jews)" (PDF). Bulletin No 28 – January 2002 (in Polish). Przemyśl: Katolickie Stowarzyszenie „Civitas Christiana”. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF 4,096 bytes) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Moroz and Datko, Męczennicy za wiarę 1939–1945, pp. 385–386 and 390–391. Stanisław Łukomski, "Wspomnienia" [in:] Rozporządzenia urzędowe Łomżyńskiej Kurii Diecezjalnej, no. 5–7 (May–July) 1974: p. 62; Witold Jemielity, “Martyrologium księży diecezji łomżyńskiej 1939–1945” [in:] Rozporządzenia urzędowe Łomżyńskiej Kurii Diecezjalnej, no. 8–9 (August–September) 1974: p. 55; Jan Żaryn, “Przez pomyłkę: Ziemia łomżyńska w latach 1939–1945.” Interview with Rev. Kazimierz Łupiński from the Szumowo Parish, Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej, no. 8–9 (September–October 2002): pp. 112–117. [Source:] Paul (2010), pp. 208–209, 210, Wartime Rescue. harvp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPaul2010 (help) Listings by Zajączkowski (1988).

- ^ a b c Jan Żaryn, The Institute of National Remembrance, The „Life for a life” project - Poles who gave their lives to save Jews

- ^ a b Kopel Kolpanitzky, Sentenced To Life: The Story of a Survivor of the Lahwah Ghetto, London and Portland, Oregon: Vallentine Mitchell, 2007, pp.89–96.

- ^ Zajączkowski (1988), Martyrs of Charity. Part One, pp. 154–155; Tsvi Weigler, “Two Polish Villages Razed for Extending Help to Jews and Partisans,” Yad Washem Bulletin, no. 1 (April 1957): pp. 19–20; Ainsztein, Jewish Resistance in Nazi-Occupied Eastern Europe, pp. 450–453; Na Rubieży (Wrocław), no. 10 (1994): pp. 10–11 (Huta Werchodudzka); Na Rubieży, no. 12 (1995): pp. 7–20 (Huta Pieniacka); Na Rubieży, no. 54 (2001): pp. 18–29.

- ^ a b Ruth Sztejnman Halperin, “The Last Days of Shumsk,” in H. Rabin, ed., Szumsk: Memorial Book of the Martyrs of Szumsk English translation from Shumsk: Sefer zikaron le-kedoshei Shumsk (Tel Aviv: Former Residents of Szumsk in Israel, 1968), pp.29ff.

- ^ a b c d e f g Władysław Bartoszewski, Zofia Lewinówna (1969), Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak, pp.533–34.

- ^ a b Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Wystawa „Sprawiedliwi wśród Narodów Świata”– 15 czerwca 2004 r., Rzeszów. „Polacy pomagali Żydom podczas wojny, choć groziła za to kara śmierci – o tym wie większość z nas.” (Exhibition "Righteous among the Nations." Rzeszów, 15 June 2004. Subtitled: "The Poles were helping Jews during the war - most of us already know that.") Last actualization 8 November 2008. Template:Pl icon

- ^ a b c d e f Jolanta Chodorska, ed., "Godni synowie naszej Ojczyzny: Świadectwa," Warsaw, Wydawnictwo Sióstr Loretanek, 2002, Part Two, pp.161–62. ISBN 83-7257-103-1 Template:Pl icon

- ^ a b Kalmen Wawryk, To Sobibor and Back: An Eyewitness Account (Montreal: The Concordia University Chair in Canadian Jewish Studies, and The Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies, 1999), pp.66–68, 71.

- ^ Ryszard Walczak (1997). Those Who Helped: Polish Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust. Warsaw: GKBZpNP–IPN. p. 51. ISBN 9788376290430. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Szymon Datner (1968). Las sprawiedliwych. Karta z dziejów ratownictwa Żydów w okupowanej Polsce. Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. p. 99.

- ^ a b Peggy Curran, "Decent people: Polish couple honored for saving Jews from Nazis," Montreal Gazette, 10 December 1994; Janice Arnold, "Polish widow made Righteous Gentile," The Canadian Jewish News (Montreal edition), 26 January 1995; Irene Tomaszewski and Tecia Werbowski, Żegota: The Council for Aid to Jews in Occupied Poland, 1942–1945, Montreal: Price-Patterson, 1999, pp.131–32.

- ^ Magazyn Internetowy Forum (26 September 2007), "Odznaczenia dla Sprawiedliwych." Znak.org.pl Template:Pl icon

- ^ a b c Dariusz Libionka, "Polska ludność chrześcijańska wobec eksterminacji Żydów—dystrykt lubelski," in Dariusz Libionka, Akcja Reinhardt: Zagłada Żydów w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej–Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, 2004), p.325. Template:Pl icon

- ^ a b Krystian Brodacki, "Musimy ich uszanować!" Tygodnik Solidarność, 17 December 2004. Template:Pl icon

- ^ a b Alina Cała, The Image of the Jew in Polish Folk Culture, Jerusalem, Magnes Press, Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1995, pp.209–10.

- ^ a b Shiye Goldberg (Szie Czechever), The Undefeated Tel Aviv, H. Leivick Publishing House, 1985, pp.166–67.

- ^ a b “Marian Małowist on History and Historians,” in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 13, 2000, p.338.

- ^ a b Gabriel Singer, "As Beasts in the Woods," in Elhanan Ehrlich, ed., Sefer Staszow, Tel Aviv: Organization of Staszowites in Israel with the Assistance of the Staszowite Organizations in the Diaspora, 1962, p. xviii (English section).

- ^ a b c Władysław Bartoszewski and Zofia Lewin, eds., Righteous Among Nations: How Poles Helped the Jews, 1939–1945, ibidem, p.361.; Gedaliah Shaiak, ed., Lowicz, A Town in Mazovia: Memorial Book, Tel Aviv: Lowitcher Landsmanshaften in Melbourne and Sydney, Australia, 1966, pp.xvi–xvii.; Wiktoria Śliwowska, ed., The Last Eyewitnesses: Children of the Holocaust Speak, Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1998, pp.120–23.; Małgorzata Niezabitowska, Remnants: The Last Jews of Poland, New York: Friendly Press, 1986, pp.118–124.

- ^ a b c d Ellen Land-Weber, To Save a Life: Stories of Holocaust Rescue (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000), pp.204–206, 246.

- ^ Nechama Tec, Resilience and Courage: Women, Men, and the Holocaust. Ibid., pp.224–27, p.29.

- ^ Natan Gross, Who Are You, Mr Grymek?, London and Portland, Oregon: Vallentine Mitchell, 2001, pp.248–49. ISBN 0-85303-411-7

- ^ IPN (30 June 2003), Communique regarding a decision to stop the investigation of the murder of Polish citizens of Jewish nationality in Jedwabne on 10 July 1941 (Komunikat dot. postanowienia o umorzeniu śledztwa w sprawie zabójstwa obywateli polskich narodowości żydowskiej w Jedwabnem w dniu 10 lipca 1941 r.) Warsaw. Internet Archive.

- ^ Bogdan Musial (11 April 2009). "The Pogrom in Jedwabne: Critical Remarks about Jan T. Gross' Neighbors". The Neighbors Respond: The Controversy over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland. Antony Polonsky, Joanna B. Michlic. Princeton University Press. pp. 323–324. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Dorota Glowacka, Joanna Zylinska, Imaginary Neighbors. University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p.7. ISBN 0803205996.

- ^ "Insight Into Tragedy". Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). The Warsaw Voice, 17 July 2003 (Internet Archive). Retrieved 1 August 2013. - ^ Joanna Michlic, The Polish Debate about the Jedwabne Massacre Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Current Trend in Antisemitism Series.

- ^ Sławomir Kapralski. The Jedwabne Village Green? The Memory and Counter-Memory of the Crime. History & Memory. Vol 18, No 1, Spring/Summer 2006, pp. 179-194. "...a genuine memory of a traumatic event is possible only in a de-centered memory space, in which no standpoints are privileged a priori."

- ^ Ruth Franklin. Epilogue. The New Republic, 2 October 2006.

- ^ "Ghettos and Camps". "No Child's Play" Exhibition. YadVashem.org. 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Emmanuel Ringelblum (Warsaw 1943, excerpts), "Polish-Jewish Relations during the Second World War." Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1974, pp. 58-88. Shoah Resource Center.

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 112, chpt. Assistance.

- ^ a b Andrzej Sławiński, Those who helped Polish Jews during WWII. Translated from Polish by Antoni Bohdanowicz. Article on the pages of the London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Last accessed on 14 March 2008.

- ^ a b c Piotrowski (1998), p. 118, chpt. Assistance.

- ^ "Irena Sendler". Auschwitz.dk. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Cesarani & Kavanaugh (2004), p. 64. Also in: Jonathan Frankel (ed), Studies in Contemporary Jewry. Volume XIII, p. 217.

- ^ a b c Piotrowski (1998), p. 117, chpt. Assistance.

- ^ a b c Delegatura. The Polish government-in-exile underground representation in Poland. Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies. PDF direct download, 45.2 KB. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ^ a b Ewa Kurek (1997), Your Life is Worth Mine: How Polish Nuns Saved Hundreds of Jewish Children in German-occupied Poland, 1939-1945. Hippocrene Books, ISBN 0781804094.

- ^ a b c John T. Pawlikowski, Polish Catholics and the Jews during the Holocaust, in, Google Print, p. 113 in Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, Rutgers University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8135-3158-6

- ^ Cesarani & Kavanaugh (2004), p. 68, nunneries.

- ^ a b c d e f Zofia Szymańska, Byłam tylko lekarzem..., Warsaw: Pax, 1979, pp.149–76.; Bertha Ferderber-Salz, And the Sun Kept Shining..., New York City: Holocaust Library, 1980, 233 pages; p.199.

- ^ a b LSIC. "Our Background". Little Servant Sisters of the Immaculate Conception. pp. 33–34. Życie za życie.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mordecai Paldiel "Churches and the Holocaust: unholy teaching, good samaritans, and reconciliation" p.209-210, KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 2006, ISBN 0-88125-908-X, ISBN 978-0-88125-908-7

- ^ a b Karski 2001, pp. 162–165.

- ^ Paul, Mark (2009). Wartime Rescue of Jews by the Polish Catholic Clergy. The Testimony of Survivors (PDF). Toronto: Polish Educational Foundation in North America. pp. 201–202.

18 Polish Priests and 32 Polish Nuns Recognized by Yad Vashem (2009)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Al Sokol, "Holocaust theme underscores work of artist," Toronto Star, 7 November 1996.

^ Władysław Bartoszewski and Zofia Lewinówna, eds., Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej, Second revised and expanded edition, Kraków: Znak, 1969, pp.741–42.

^ Tadeusz Kozłowski, "Spotkanie z żydowskim kolegą po 50 latach," Gazeta (Toronto), 12–14 May 1995.

^ Frank Morgens, Years at the Edge of Existence: War Memoirs, 1939–1945, Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America, 1996, pp.97, 99.

^ Władysław Bartoszewski and Zofia Lewin, eds., Righteous Among Nations: How Poles Helped the Jews, 1939–1945, London: Earlscourt Publications, 1969, p.361. - ^ John T. Pawlikowski. Polish Catholics and the Jews during the Holocaust. In: Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, Rutgers University Press, 2003

- ^ Bogner, Nahum (2012). "The Convent Children. The Rescue of Jewish Children in Polish Convents During the Holocaust" (PDF). Shoah Resource Center: 41–44. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2012 – via direct download, 45.2 KB.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) See also: Phayer, Michael (2000). The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965. Indiana University Press. pp. 113, 117–120, 250. ISBN 0253214718. In January 1941 Jan Dobraczynski placed roughly 2,500 children in cooperating convents of Warsaw. Matylda Getter took many of them into her convent. During the Ghetto uprising the number of Jewish orphans in their care surged upward.[p.120]. - ^ a b c d Yad Vashem, staff writer (archived 5 June 2011), "Delegatura." The summary journal entry. Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies.

- ^ Norman Davies, Europe: A History, Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-19-820171-0., Google Print, p. 1023

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dariusz Stola (2003), The Polish government in exile and the Final Solution: What conditioned its actions and inactions? (404 Error) In: Joshua D. Zimmerman, ed. Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813531586