Haitian Vodou: Difference between revisions

→Names and etymology: added referenced information from Fernandez Olmos et al |

→Misconceptions: renaming section as "Reception"; "Misconceptions" is not a commonly used title in WIkipedia. |

||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

== |

==Reception== |

||

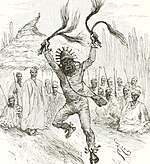

[[File:Affaire de Bizoton 1864.png|thumb|The ''Affaire de Bizoton'' of 1864. The murder and alleged canibalization of a woman's body by eight voodoo devotees caused a scandal worldwide and was taken as proof of the evil nature of voodoo.]] |

[[File:Affaire de Bizoton 1864.png|thumb|The ''Affaire de Bizoton'' of 1864. The murder and alleged canibalization of a woman's body by eight voodoo devotees caused a scandal worldwide and was taken as proof of the evil nature of voodoo.]] |

||

Revision as of 13:54, 15 May 2020

It has been suggested that Haitian mythology be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since November 2019. |

| Part of a series on Haitian Vodou |

|---|

|

| Mythology |

| Practice |

| Culture |

| Influenced |

Haitian Vodou[1][2][3] (/ˈvoʊduː/, French: [vodu], also written as Vaudou /ˈvoʊduː/;[4][5] known commonly as Voodoo[6][7] /ˈvuːduː/, sometimes as Vodun[8][9] /ˈvoʊduː/, Vodoun[8][10] /ˈvoʊduːn/, Vodu[6] /ˈvoʊduː/, or Vaudoux[6] /ˈvoʊduː/) is a syncretic[11] religion based on West African Vodun, practiced chiefly in Haiti and the Haitian diaspora. Practitioners are called "vodouists" (French: vodouisants [voduizɑ̃]) or "servants of the spirits" (Haitian Creole: sèvitè).[12]

Vodouists believe in a distant and unknowable Supreme Creator, Bondye (derived from the French Bon Dieu, meaning "good God"). According to Vodouists, Bondye does not intercede in human affairs, and thus they direct their worship toward spirits subservient to Bondye, called loa.[13] Every loa is responsible for a particular aspect of life, with the dynamic and changing personalities of each loa reflecting the many possibilities inherent to the aspects of life over which they preside.[14] To navigate daily life, vodouists cultivate personal relationships with the loa through the presentation of offerings, the creation of personal altars and devotional objects, and participation in elaborate ceremonies of music, dance, and spirit possession.[15]

Vodou originated in what is now Benin and developed in the French colonial empire in the 18th century among West African peoples who were enslaved, when African religious practice was actively suppressed, and enslaved Africans were forced to convert to Christianity.[16][17] Religious practices of contemporary Vodou are descended from, and closely related to, West African Vodun as practiced by the Fon and Ewe. Vodou also incorporates elements and symbolism from other African peoples including the Yoruba and Kongo; as well as Taíno religious beliefs, Roman Catholicism, and European spirituality including mysticism and other influences.[18]

In Haiti, some Catholics combine aspects of Catholicism with aspects of Vodou, a practice forbidden by the Church and denounced as diabolical by Haitian Protestants.[19]

Names and etymology

Vodou is a Haitian Creole word that formerly referred to only a small subset of Haitian rituals.[20] The word derives from an Ayizo word referring to mysterious forces or powers that govern the world and the lives of those who reside within it, but also a range of artistic forms that function in conjunction with these vodun energies.[21] Two of the major speaking populations of Ayizo are the Ewe and the Fon—European slavers called both the Arada. These two peoples composed a sizable number of the early enslaved population in St. Dominigue. In Haiti, practitioners occasionally use "Vodou" to refer to Haitian religion generically, but it is more common for practitioners to refer to themselves as those who "serve the spirits" (sèvitè) by participating in ritual ceremonies, usually called a "service to the loa" (sèvis lwa) or an "African service" (sèvis gine).[20] These terms also refer to the religion as a whole.

Outside of Haiti, the term Vodou refers to the entirety of traditional Haitian religious practice.[20] Originally written as vodun, it is first recorded in Doctrina Christiana, a 1658 document written by the King of Allada's ambassador to the court of Philip IV of Spain.[21] In the following centuries, Vodou was eventually taken up by non-Haitians as a generic descriptive term for traditional Haitian religion.[20] There are many used orthographies for this word. Today, the spelling Vodou is the most commonly accepted orthography in English.[10] Other potential spellings include Vodoun, vaudou, and voodoo, with vau- or vou- prefix variants reflecting French orthography, and a final -n reflecting the nasal vowel in West African or older, non-urbanized, Haitian Creole pronunciations.

The spelling voodoo, once very common, is now generally avoided by Haitian practitioners and scholars when referring to the Haitian religion.[8][22][23][24] This is both to avoid confusion with Louisiana Voodoo,[25] a related but distinct set of religious practices, as well as to separate Haitian Vodou from the negative connotations and misconceptions the term "voodoo" has acquired in popular culture.[3][26] Over the years, practitioners and their supporters have called on various institutions including the Associated Press to redress this misrepresentation by adopting "Vodou" in reference to the Haitian religion. In October 2012, the Library of Congress decided to change their subject heading from "Voodooism" to Vodou in response to a petition by a group of scholars and practitioners in collaboration with KOSANBA, the scholarly association for the study of Haitian Vodou based at University of California Santa Barbara.[27]

Vodou is one of the most complex of the Afro-American traditions.[28] The anthropologist Paul Christopher Johnson characterized Haitian Vodou, Cuban Santería, and Brazilian Candomblé as "sister religions" due to their shared origins in Yoruba traditional belief systems.[29]

Beliefs

| Part of a series on Vodun related religions called |

| Voodoo |

|---|

|

Vodou is popularly described as not simply a religion, but rather an experience that ties body and soul together. The concept of tying that exists in Haitian religious culture is derived from the Congolese tradition of kanga, the practice of tying one's soul to something tangible. This "tying of soul" is evident in many Haitian Vodou practices that are still exercised today.[30]

Spirits

Vodou teaches the existence of single supreme god,[31] and in this has been described as "essentially a monotheistic religion."[31] This entity, which is believed to have created the universe, is known as the Grand Mèt, Bondyé, or Bonié.[32] The latter name derives from the French Bon Dieu (God).[33] For Vodou practitioners, the Bondyé is regarded as a remote and transcendent figure.[33] Haitians will frequently use the phrase si Bondye vie (if Bondye is willing), suggesting a broader belief that all things occur in accordance with this creator deity's will.[33]

Vodou also teaches the existence of a broader range of deities, known as the lwa or loa.[34] These are also known as the mystères, anges, saints, and les invisibles.[31] The lwa can offer help, protection, and counsel to human beings, in return for ritual service.[28] The lwa are associated with specific Roman Catholic saints.[35] For instance, Azaka, the lwa of agriculture, is associated with Saint Isidora the farmer.[35] Similarly, the lwa of love and luxury, Ezili Frida, is associated with Mater Dolorosa.[35]

Dressing the Spirit (Lwa)

In dressing the spirits there is a powerful relation in which is followed. There is an aura of sorts and with each form of cloth (there are many different styles and props used) there might be a different spirit (Lwa) attached to that specific style. This way of dress can be seen in a more contemporary style where there is this balance of having power to being powerless. The workings or ritual side of "dress in Vodou cultural production lies in the tension between inner and outer selves; the material, the physical and the spiritual; the seen and the unseen."[36](Hammond pg:89).

Loa

Since Bondye (God) is considered unreachable, Vodouisants aim their prayers to lesser entities, the spirits known as loa, or mistè. The most notable loa include Papa Legba (guardian of the crossroads), Erzulie Freda (the spirit of love), Simbi (the spirit of rain and magicians), Kouzin Zaka (the spirit of agriculture), and The Marasa, divine twins considered to be the first children of Bondye.[37]

These loa can be divided into 21 nations, which include the Petro, Rada, Congo, and Nago.[38]

Each of the loa is associated with a particular Roman Catholic saint. For example, Legba is associated with St. Anthony the Hermit, and Damballa is associated with St. Patrick.[39]

The loa also fall into family groups who share a surname, such as Ogou, Ezili, Azaka or Ghede. For instance, "Ezili" is a family, Ezili Danto and Ezili Freda are two individual spirits in that family. Each family is associated with a specific aspect, for instance the Ogou family are soldiers, the Ezili govern the feminine spheres of life, the Azaka govern agriculture, the Ghede govern the sphere of death and fertility.

Morality

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2010) |

Vodou's moral code focuses on the vices of dishonor and greed. There is also a notion of relative propriety—and what is appropriate to someone with Dambala Wedo as their head may be different from someone with Ogou Feray as their head. For example, one spirit is very cool and the other is very hot. Coolness overall is valued, and so is the ability and inclination to protect oneself and one's own if necessary. Love and support within the family of the Vodou society seem to be the most important considerations. Generosity in giving to the community and to the poor is also an important value. One's blessings come through the community, and one should be willing to give back. There are no "solitaries" in Vodou—only people separated geographically from their elders and house. A person without a relationship of some kind with elders does not practice Vodou as it is understood in Haiti and among Haitians; additionally, Haitian Vodou emphasizes the 'wholeness of being' not just with elders and the material world, but also unity with the interconnected forces of nature.[40]

There is a diversity of practice in Vodou across the country of Haiti and the Haitian diaspora. For instance, in the north of Haiti, the lave tèt ("head washing")[41] or kanzwe may be the only initiation, as it is in the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Puerto Rico, whereas in Port-au-Prince and the south they practice the kanzo rites[42] with three grades of initiation – kanzo senp, si pwen, and asogwe – and the latter is the most familiar mode of practice outside Haiti. Some lineages combine both, as Mambo Katherine Dunham reports from her personal experience in her book Island Possessed.

While the overall tendency in Vodou is conservative in accord with its African roots, there is no singular, definitive form, only what is right in a particular house or lineage. Small details of service and the spirits served vary from house to house, and information in books or on the internet therefore may seem contradictory. There is no central authority or "pope" in Haitian Vodou, since "every mambo and houngan is the head of their own house", as a popular Haitian saying goes. Another consideration in terms of Haitian diversity are the many sects besides the Sèvi Gine in Haiti such as the Makaya, Rara, and other secret societies, each of which has its own distinct pantheon of spirits.

Soul

According to Vodou, the soul consists of two aspects, in a type of soul dualism: the gros bon ange (big good angel) and the ti bon ange (little good angel). The gros bon ange is the part of the soul that is essentially responsible for the basic biological functions, such as the flow of blood through the body and breathing. On the other hand, the ti bon ange is the source of personality, character and willpower. "As the gros bon ange provides each person with the power to act, it is the ti bon ange that molds the individual sentiment within each act".[43] While the latter is an essential element for the survival of one's individual identity, it is not necessary to keep the body functioning properly in biological terms, and therefore a person can continue to exist without it.

Haitian Dress in the Vodou Practice

Charlotte Hammond, finds this source from three sources pertaining with this idea of dress in the Haitian Vodou practice to be a good kick off within the section "Decoding Dress" from the anthology; Vodou in the Haitian Experience: A Black Atlantic Perspective. It states that "the importance of the materiality of dress and fabric, in Haiti as a mediator between spirits and people, and in organizing society, is a belief which can be traced to West African Yoruban culture" (Buckridge, Tselos, Farris Thompsan). Haitian dress and the practice of Vodou are tied together, but with the great importance of other pieces dealing with the religion "such as dance, music, and song."[44] Dance, music, and song being the spotlighted points of interest regarding the Hatiain Vodou practice the idea of dress and cloth gets overlooked easily. However, there is power in dress and what is worn. There is a power change in the identity of practices of Haitian Vodou. Dress and the Vodou religion have a great importance and power that ties within the spirit, the soul, the emotion in which the dress is symbolized and handled. Dress allows for the wearer to not only connect in a spiritual way, but also in a self identifying way.

Practices

Vodou ceremonies revolve around song, drumming, dance, prayer, possession, and animal sacrifice.[28]

Liturgy and practice

A Haitian Vodou temple is called a Peristil.[45] After a day or two of preparation setting up altars at an Hounfour, and ritually preparing and cooking fowl and other foods, a Haitian Vodou service begins with a series of prayers and songs in French, then a litany in Haitian Creole and Langaj that goes through all the European and African saints and loa honored by the house, and then a series of verses for all the main spirits of the house. This is called the "Priyè Gine" or the African Prayer. After more introductory songs, beginning with saluting Hounto, the spirit of the drums, the songs for all the individual spirits are sung, starting with the Legba family through all the Rada spirits, then there is a break and the Petro part of the service begins, which ends with the songs for the Gede family.

As the songs are sung, participants believe that spirits come to visit the ceremony, by taking possession of individuals and speaking and acting through them. When a ceremony is made, only the family of those possessed is benefited. At this time it is believed that devious mambo or houngan can take away the luck of the worshippers through particular actions. For instance, if a priest asks for a drink of champagne, a wise participant refuses. Sometimes these ceremonies may include dispute among the singers as to how a hymn is to be sung. In Haiti, these Vodou ceremonies, depending on the Priest or Priestess, may be more organized. But in the United States, many vodouists and clergy take it as a sort of non-serious party or "folly". In a serious rite, each spirit is saluted and greeted by the initiates present and gives readings, advice, and cures to those who ask for help. Many hours later, as morning dawns, the last song is sung, the guests leave, and the exhausted hounsis, houngans, and mambos can go to sleep.

Vodou practitioners believe that if one follows all taboos imposed by their particular loa and is punctilious about all offerings and ceremonies, the loa will aid them. Vodou practitioners also believe that if someone ignores their loa it can result in sickness, the failure of crops, the death of relatives, and other misfortunes.[46] Animals are sometimes sacrificed in Haitian Vodou. A variety of animals are sacrificed, such as pigs, goats, chickens, and bulls. "The intent and emphasis of sacrifice is not upon the death of the animal, it is upon the transfusion of its life to the loa; for the understanding is that flesh and blood are of the essence of life and vigor, and these will restore the divine energy of the god."[47]

On the individual's household level, a Vodouisant or "sèvitè"/"serviteur" may have one or more tables set out for their ancestors and the spirit or spirits that they serve with pictures or statues of the spirits, perfumes, foods, and other things favored by their spirits. The most basic set up is just a white candle and a clear glass of water and perhaps flowers. On a particular spirit's day, one lights a candle and says an Our Father and Hail Mary, salutes Papa Legba and asks him to open the gate, and then one salutes and speaks to the particular spirit as an elder family member. Ancestors are approached directly, without the mediating of Papa Legba, since they are said to be "in the blood".

In a Vodou home, the only recognizable religious items are often images of saints and candles with a rosary. In other homes, where people may more openly show their devotion to the spirits, noticeable items may include an altar with Catholic saints and iconographies, rosaries, bottles, jars, rattles, perfumes, oils, and dolls. Some Vodou devotees have less paraphernalia in their homes because they had no option but to hide their beliefs. Haiti is a rural society and the cult of ancestors guard the traditional values of the peasant class. The ancestors are linked to family life and the land. Haitian peasants serve the spirits daily and sometime gather with their extended family on special occasions for ceremonies, which may celebrate the birthday of a spirit or a particular event. In very remote areas, people may walk for days to partake in ceremonies that take place as often as several times a month. Vodou is closely tied to the division and administration of land as well as to the residential economy. The cemeteries and many crossroads are meaningful places for worship: the cemetery acts as a repository of spirits and the crossroads acts as points of access to the world of the invisible.[48]

Priests

Houngans (priest) or Mambos (priestess) are usually people who were chosen by the dead ancestors and received the divination from the deities while he or she was possessed. His or her tendency is to do good by helping and protecting others from spells, however they sometimes use their supernatural power to hurt or kill people. They also conduct ceremonies that usually take place "amba peristil" (under a Vodou temple). However, non-Houngan or non-Mambo as Vodouisants are not initiated, and are referred to as being "bossale"; it is not a requirement to be an initiate to serve one's spirits. There are clergy in Haitian vodou whose responsibility it is to preserve the rituals and songs and maintain the relationship between the spirits and the community as a whole (though some of this is the responsibility of the whole community as well). They are entrusted with leading the service of all of the spirits of their lineage. Sometimes they are "called" to serve in a process called being reclaimed, which they may resist at first.[49] Below the houngans and mambos are the hounsis, who are initiates who act as assistants during ceremonies and who are dedicated to their own personal mysteries.

The asson (calabash rattle) is the symbol for one who has acquired the status of houngan or mambo (priest or priestess) in Haitian Vodou. The calabash is taken from the calabasse courante or calabasse ordinaire tree, which is associated with Danbhalah-Wédo. A houngan or mambo traditionally holds the asson in their hand, along with a clochette (bell). The asson contains stones and snake vertebrae that give it its sound. The asson is covered with a web of porcelain beads.[50]

A bokor is a sorcerer or magician who casts spells on request. They are not necessarily priests, and may be practitioners of "darker" things, and are often not accepted by the mambo or the houngan.

Bokor can also be a Haitian term for a Vodou priest or other practitioner who works with both the light and dark arts of magic.[51][circular reference] The bokor, in that sense, deals in baka' (malevolent spirits contained in the form of various animals).[52]

Death and the afterlife

Practitioners of Vodou revere death, and believe it is a great transition from one life to another, or to the afterlife. Some Vodou families believe that a person's spirit leaves the body, but is trapped in water, over mountains, in grottoes—or anywhere else a voice may call out and echo—for one year and one day. After then, a ceremonial celebration commemorates the deceased for being released into the world to live again. In the words of Edwidge Danticat, author of "A Year and a Day"—an article about death in Haitian society published in the New Yorker—and a Vodou practitioner, "The year-and-a-day commemoration is seen, in families that believe in it and practice it, as a tremendous obligation, an honorable duty, in part because it assures a transcendental continuity of the kind that has kept us Haitians, no matter where we live, linked to our ancestors for generations." After the soul of the deceased leaves its resting place, it can occupy trees, and even become a hushed voice on the wind. Though other Haitian and West African families believe there is an afterlife in paradise in the realm of God.[53]

History

Before 1685: From Africa to the Caribbean

The cultural area of the Fon, Ewe, and Yoruba peoples share a common metaphysical conception of a dual cosmological divine principle consisting of Nana Buluku, the God-Creator, and the voduns(s) or God-Actor(s), daughters and sons of the Creator's twin children Mawu (goddess of the moon) and Lisa (god of the sun). The God-Creator is the cosmogonical principle and does not trifle with the mundane; the voduns(s) are the God-Actor(s) who actually govern earthly issues. The pantheon of vodoun is quite large and complex.

West African Vodun has its primary emphasis on ancestors, with each family of spirits having its own specialized priest and priestess, which are often hereditary. In many African clans, deities might include Mami Wata, who are gods and goddesses of the waters; Legba, who in some clans is virile and young in contrast to the old man form he takes in Haiti and in many parts of Togo; Gu (or Ogoun), ruling iron and smithcraft; Sakpata, who rules diseases; and many other spirits distinct in their own way to West Africa.

A significant portion of Haitian Vodou often overlooked by scholars until recently is the input from the Kongo. The entire northern area of Haiti is heavily influenced by Kongo practices. In northern Haiti, it is often called the Kongo Rite or Lemba, from the Lemba rituals of the Loango area and Mayombe. In the south, Kongo influence is called Petwo (Petro). Many loa (a Kikongo term) are of Kongo origin such as Basimba belonging to the Basimba people and the Lemba.[54]

In addition, the Vodun religion (distinct from Haitian Vodou) already existed in the United States previously to Haitian immigration, having been brought by enslaved West Africans, specifically from the Ewe, Fon, Mina, Kabaye, and Nago groups. Some of the more enduring forms survive in the Gullah Islands.

European colonialism, followed by totalitarian regimes in West Africa, suppressed Vodun as well as other forms of the religion. However, because the Vodun deities are born to each African clan-group, and its clergy is central to maintaining the moral, social, and political order and ancestral foundation of its villagers, it proved to be impossible to eradicate the religion.

1685-1791: Vodou in colonial Saint-Domingue

The majority of the Africans who were brought as slaves to Haiti were from Western and Central Africa. The survival of the belief systems in the New World is remarkable, although the traditions have changed with time and have even taken on some Catholic forms of worship.[55] Two important factors, however, characterize the uniqueness of Haitian Vodou as compared to African Vodun; the transplanted Africans of Haiti, similar to those of Cuba and Brazil, were obliged to disguise their loa or spirits as Roman Catholic saints, an element of a process called syncretism.

Two keys provisions of the Code Noir by King Louis XIV of France in 1685 severely limited the ability of enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue to practice African religions. First, the Code Noir explicitly forbade the open practice of all African religions.[17] Second, it forced all slaveholders to convert their slaves to Catholicism within eight days of their arrival in Saint-Domingue.[17] Despite French efforts, enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue were able to cultivate their own religious practices. Enslaved Africans spent their Sunday and holiday nights expressing themselves. While bodily autonomy was strictly controlled during the day at night, the enslaved Africans wielded a degree of agency. They began to continue their religious practices but also used the time to cultivate community and reconnect the fragmented pieces of their various heritages. These late night reprieves were a form of resistance against white domination and also created community cohesion between people from vastly different ethnic groups.[56] While Catholicism was used as a tool for suppression, enslaved Haitians, partly out of necessity, would go on to incorporate aspects of Christianity into their Vodou.[17] Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry, a French observer writing in 1797, noted this religious syncretism, commenting that the Catholic-style altars and votive candles used by Africans in Haiti were meant to conceal the Africanness of the religion,[57] but the connection goes much further than that. Vodounists superimposed Catholic saints and figures onto the Iwa/Ioa, major spirits that work as agents of the Grand Met.[58] Some examples of major Catholic idols re-imagined as Iwa are the Virgin Mary being seen as Ezili. Saint Jacques as Ogou, and Saint Patrick as Dambala.[58] Vodou ceremonies and rituals also incorporated some Catholic elements such as the adoption of the Catholic calendar, the use of holy water in purification rituals, singing hymns, and the introduction of Latin loanwords into Vodou lexicon.[58]

1791–1804: The Haitian Revolution

Vodou was a powerful political and cultural force in Haiti.[59]The most historically iconic Vodou ceremony in Haitian history was the Bois Caïman ceremony of August 1791 that took place on the eve of a slave rebellion that predated the Haitian Revolution.[60] During the ceremony the spirit Ezili Dantor possessed a priestess and received a black pig as an offering, and all those present pledged themselves to the fight for freedom.[61] While there is debate on whether or not Bois Caiman was truly a Vodou ritual, the ceremony also served as a covert meeting to iron out details regarding the revolt.[60] Vodou ceremonies often held a political secondary function that strengthened bonds between enslaved people while providing space for organizing within the community. Vodou thus gave slaves a way both a symbolic and physical space of subversion against their French masters.[59]

Political leaders such as Boukman Dutty, a slave who helped plan the 1791 revolt, also served as religious leader, connecting Vodou spirituality with political action.[62] Bois Caiman has often been cited as the start of the Haitian Revolution but the slave uprising had already been planned weeks in advance,[60] proving that the thirst for freedom had always been present. The revolution would free the Haitian people from French colonial rule in 1804 and establish the first black people's republic in the history of the world and the second independent nation in the Americas. Haitian nationalists have frequently drawn inspiration by imagining their ancestors' gathering of unity and courage. Since the 1990s, some neo-evangelicals have interpreted the politico-religious ceremony at Bois Caïman to have been a pact with demons. This extremist view is not considered credible by mainstream Protestants, however conservatives such as Pat Robertson repeat the idea.[63]

Vodou in 19th-century Haiti

1804: Liberty, Isolation, Boycott

On 1 January 1804 the former slave Jean-Jaqcues Dessalines (as Jacques I) declared the independence of St. Domingue as the First Black Empire; two years later, after his assassination, it became the Republic of Haiti. This was the second nation to gain independence from European rule (after the United States), and the only state to have arisen from the liberation of slaves. No nation recognized the new state, which was instead met with isolation and boycotts. This exclusion from the global market led to major economic difficulties for the new state.

Many of the leaders of the revolt disassociated themselves from Vodou. They strived to be accepted as Frenchmen and good Catholics rather than as free Haitians. Yet most practitioners of Vodou saw, and still see, no contradiction between Vodou and Catholicism, and also take part in Catholic masses.

1835: Vodou made punishable, secret societies

The new Haitian state did not recognize Vodou as an official religion. In 1835, the government made practising Vodou punishable. Secret Vodou societies therefore continued to be important. These societies also provided the poor with protection and solidarity against the exercising of power by the elite. They had their own symbols and codes.

20th century to the present

Today, Vodou is practiced not only by Haitians but by Americans and people of many other nations who have been exposed to Haitian culture. Related forms of Vodou exist in other countries in the forms of Dominican Vudú, Cuban Vodú,[64], Brazilian Vodum, and also in places to which Haitians have immigrated. There has been a re-emergence of the Vodun traditions in the United States, maintaining the same ritual and cosmological elements as in West Africa.

Former president of Haiti François Duvalier (also known as Papa Doc) played a role in elevating the status of Vodou into a national doctrine. Duvalier was involved in the noirisme movement and hoped to re-value cultural practices that had their origins in Africa. Duvalier manipulated Vodou to suit his purposes throughout his Reign of Terror. He organized the Vodou priests in the countryside and had them advance his agenda, instilling fear through promoting the belief that he had supernatural powers playing into the religion's mysticism.[65][66]

Many Haitians involved in the practice of Vodou have been initiated as Houngans or Mambos. In January 2010, after the Haiti earthquake traditional ceremonies were organized to appease the spirits and seek the blessing of ancestors for the Haitians. Also a "purification ceremony" was planned for Haiti.

Controversy after the 2010 earthquake

Following the 2010 Haiti earthquake, there were verbal and physical attacks against vodou practitioners in Haiti perpetrated by those who felt that vodouists were partially responsible for the natural disaster. Furthermore, during a Cholera outbreak in 2010 several Vodou priests were lynched by mobs who believed them to be spreading the disease.[67]

Demographics and geographic distribution

Because of the religious syncretism between Catholicism and Vodou, it is difficult to estimate the number of Vodouists in Haiti. The CIA currently estimates that approximately 50% of Haiti's population practices Vodou, with nearly all Vodouists participating in one of Haiti's Christian denominations.[68]

Gallery of Haitian Vodou objects

-

Ceremonial suit

-

Statue of a djab, a quick-working wild spirit.

-

Ceremonial drum

-

Banner reading "Trop Pou Te" in the Haitian Creole language

-

Mirrors represent doorways to the world of the dead.

Reception

Vodou has often been associated in popular culture with Satanism, witchcraft, zombies and "voodoo dolls". Zombie creation has been referenced within rural Haitian culture,[69] but is not a part of Vodou. Such manifestations fall under the auspices of the bokor or sorcerer, rather than the priest of the loa. The practice of sticking pins in voodoo dolls has history in folk magic. "Voodoo dolls" are often associated with New Orleans Voodoo and Hoodoo as well the magical devices of the poppet and the nkisi or bocio of West and Central Africa.

The general fear of Vodou in the US can be traced back to the end of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804). There is a legend that Haitians were able to beat the French during the Haitian Revolution because their Vodou deities made them invincible. The US, seeing the tremendous potential Vodou had for rallying its followers and inciting them to action, feared the events at Bois Caïman could spill over onto American soil. After the Haitian Revolution many Haitians fled as refugees to New Orleans. Free and enslaved Haitians who moved to New Orleans brought their religious beliefs with them and reinvigorated the Voodoo practices that were already present in the city. Eventually, Voodoo in New Orleans became hidden and the magical components were left present in the public sphere. This created what is called hoodoo in the southern part of the United States. Because hoodoo is folk magic, Voodoo and Afro-diasporic religions in the U.S. became synonymous with fraud. This is one origin of the stereotype that Haitian Vodou, New Orleans Voodoo, and hoodoo are all tricks used to make money off the gullible.[70]

The elites preferred to view it as folklore in an attempt to render it relatively harmless as a curiosity that might continue to inspire music and dance.[71]

Fearing an uprising in opposition to the US occupation of Haiti (1915-1934), political and religious elites, along with Hollywood and the film industry, sought to trivialize the practice of Vodou. Hollywood often depicts Vodou as evil and having ties to Satanic practices in movies such as White Zombie, The Devil's Advocate, The Blair Witch Project, The Serpent and the Rainbow, Child's Play, Live and Let Die, and in children's movies like The Princess and the Frog, though this last example countered this trope with a kindly voodoo priestess who helps the main characters.

In 2010, a 7.0 earthquake that devastated Haiti brought negative attention to Vodou. Televangelist Pat Robertson stated that the country had cursed itself after the events at Bois Caïman, because he claimed they had engaged in Satanic practices in the ceremony preceding the Haitian Revolution. "They were under the heel of the French, you know, Napoleon the third and whatever. And they got together and swore a pact to the devil. They said 'We will serve you if you will get us free from the prince.' True story. And so the devil said, 'Ok it's a deal.' And they kicked the French out. The Haitians revolted and got something themselves free. But ever since they have been cursed by one thing after another."[72][73]

KOSANBA

Scholarly research on Vodou and other African spiritual retentions in Haiti started in the early 20th century with chronicles such as Zora Neale Hurston's "Tell My Horse", amongst others. Other notable early scholars of Haitian Vodou one could cite are Milo Rigaud, Alfred Metraux and Maya Deren, for example. In April 1997, thirteen scholars gathered at the University of California Santa Barbara for a colloquium on Haitian Vodou. From that meeting the Congress of Santa Barbara was created, also known as KOSANBA.[74] These scholars felt there was a need for access to scholarly resources and course offerings studying Haitian Vodou, and pledged, "...to create a space where scholarship on Vodou can be augmented."[75] As further described in the Congress’ declaration:

"The presence, role, and importance of Vodou in Haitian history, society, and culture are unarguable, and recognizably a part of the national ethos. The impact of the religion qua spiritual and intellectual disciplines on popular national institutions, human and gender relations, the family, that plastic arts, philosophy and ethics, oral and written literature, language, popular and sacred music, science and technology and the healing arts, is indisputable. It is the belief of the Congress that Vodou plays, and shall continue to play, a major role in the grand scheme of Haitian development and in the socio-economic, political, and cultural arenas. Development, when real and successful, always comes from the modernization of ancestral traditions, anchored in the rich cultural expressions of a people."[75]

In the fall of 2012, KOSANBA successfully petitioned the Library of Congress to change the terms "voodoo" and "voodooism" to the correct spelling "Vodou".[76]

See also

- Afro-American religion

- Haitian mythology

- Haitian Vodou art

- Hoodoo

- Juju

- Louisiana Voodoo

- West African Vodun

- Witch doctor

- Simbi

Footnotes

- ^ Cosentino 1995a, p. xiii-xiv.

- ^ Brown 1991.

- ^ a b Fandrich 2007, p. 775.

- ^ Michel, Claudine (1996). "Of Worlds Seen and Unseen: The Educational Character of Haitian Vodou". Comparative Education Review. 40 (3). The University of Chicago Press: 280–294. doi:10.1086/447386. JSTOR 1189105.

- ^ Piquion, René (2002). "Réflexion: Vaudou et Société en Haïti". Journal of Haitian Studies. 8 (2). Center for Black Studies Research: 167–176. JSTOR 41715143.

- ^ a b c Corbett, Bob, The Spelling of Voodoo, 1998

- ^ Haas, Saumya Arya, ed. (25 May 2011). "What is Voodoo? Understanding a Misunderstood Religion". Huffington Post. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Courlander 1988, p. 88.

- ^ Thompson 1983, p. 163–191.

- ^ a b Cosentino 1995a, p. xiv.

- ^ Stevens-Arroyo 2002, p. 37-58.

- ^ Cosentino 1995b, p. 25.

- ^ Gordon 2000, p. 48.

- ^ Brown 1991, p. 6.

- ^ Brown 1991, p. 4–7.

- ^ Gordon 2000, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Desmangles 1990, p. 475.

- ^ Cosentino 1995b, p. 25-55.

- ^ Rey, Terry; Stepick, Alex (2013-08-19). Crossing the Water and Keeping the Faith:Haitian Religion in Miami. NYU Press. ISBN 9781479820771.

- ^ a b c d Brown 1995, p. 205.

- ^ a b Blier 1995, p. 61.

- ^ Lane 1949, p. 1162.

- ^ Thompson 1983, p. 163.

- ^ Cosentino 1988, p. 77.

- ^ Fandrich 2007, p. 780.

- ^ Hurbon 1995, p. 181-197.

- ^ For a fuller description of transitions in spelling, see: From Voodoo to Vodou

- ^ a b c Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 117.

- ^ Johnson 2002, p. 9.

- ^ Rey, Terry; Karen Richman (2010). "The Somatics of Syncretism: Tying Body and Soul in Haitian Religion". Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses. 39 (3): 279–403. doi:10.1177/0008429810373321. Retrieved 2013-09-22.

- ^ a b c Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 120.

- ^ Ramsey 2011, p. 7; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 120.

- ^ a b c Ramsey 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 117, 120.

- ^ a b c Ramsey 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Hammond, Charlotte. "Voudou in the Haitian Experience: A Black Atlantic Perspective". Decoding Dress: 85–96.

- ^ Gordon 2000, p. 54.

- ^ Alvarado 2011.

- ^ Simpson, George (1978). Black Religions in the New World. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 66.

- ^ Michel, Claudine (September 1, 2001). "Women's Moral and Spiritual Leadership in Haitian Vodou: The Voice of Mama Lola and Karen McCarthy Brown". Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 17 (2).

- ^ Daniels, Kyrah Malika (Fall 2016). "The Coolness of Cleansing: Sacred Waters, Medicinal Plants and Ritual Baths of Haiti and Peru". Revista: Harvard Review of Latin America. 16 (1): 21–24.

- ^ Richman, Karen E. (August 1, 2007). "Peasants, Migrants and the Discovery of African Traditions: Ritual and Social Change in Lowland Haiti". Journal of Religion in Africa. 37 (3): 383–387.

- ^ Thomas, Kette. "Haitian Zombie, Myth, and Modern Identity." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 12.2 (2010): n. pag. Web. 29 Oct. 2013.

- ^ Hammond, Charlotte. Decoding Dress: Vodou, Cloth and Colonial Resistance in Pre- and Postrevolutionary Haiti. p. 85.

- ^ Kilson & Rotberg 1976, p. 345.

- ^ Simpson, George (1978). Black Religions in the New World. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 86.

- ^ Deren, Maya (1953). Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. New York: Thames and Hudson. p. 216.

- ^ Michel, Claudine (Aug 1996). "Of Worlds Seen and Unseen: The Educational Character of Haitian Vodou". Comparative Education Review (The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Comparative and International Education) 40. Retrieved Dec 5, 2013.

- ^ McAlister 1993, pp. 10–27.

- ^ Rigaud, Milo (2001). Secrets of Voodoo. New York: City Lights Publishers. pp. 35–36.

- ^ Bokor

- ^ Deren, Maya (1953). Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. New York: Thames and Hudson. p. 75.

- ^ Danticat, Edwidge. "A Year And A Day." The New Yorker 17 Jan. 2011: 19. Popular Culture Collection. Web. 26 September. 2013.

- ^ The Book of Life, Knowledge and Confidence, Pacific Press, 2012, p. 112

- ^ Stevens-Arroyo 2002.

- ^ Fick, Carolyn. "Slavery and Slave Society," in the Making of Haiti. p. 39.

- ^ Moreau de Saint-Méry 1797.

- ^ a b c Edmonds, Ennis Barrington (2010). Caribbean Religious History: An Introduction. New York City: New York Univ. Press. p. 112.

- ^ a b Squint, Kirsten L. (2007). "Vodou and Revolt in Literature of the Haitian Revolution". CLA Journal. 2: 170 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Geggus, David (2002). Haitian Revolutionary Studies. Indiana University Press. pp. 84–85.

- ^ Markel 2009.

- ^ Dubois, Laurent (2004). Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. p. 99.

- ^ McAlister, Elizabeth (June 2012). "From Slave Revolt to a Blood Pact with Satan: The Evangelical Rewriting of Haitian History". Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses. 41 (2): 187–215. doi:10.1177/0008429812441310.

- ^ Stevens-Arroyo 2002, pp. 37–58.

- ^ Time Magazine (Jan 17, 2011). "The Death and Legacy of Papa Doc Duvalier" Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ^ Apter, Andrew (May 2002). "On African Origins: Creolization and Connaissance in Haitian Vodou". American Ethnologist (Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association) 29. Retrieved Dec 8, 2013.

- ^ Valme 2010.

- ^ CIA World Factbook.

- ^ Davis 1988.

- ^ Long, Carolyn Morrow (Oct 2002). "Perceptions of New Orleans Voodoo: Sin, Fraud, Entertainment and Religion". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions (University of California Pres) 6. Retrieved Dec 5, 2013.

- ^ Bellegarde-Smith, P. (2006). Haitian Vodou: Spirit, Myth and Reality. (p. 25). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press

- ^ "Pat Robertson: Haiti "Cursed" After "Pact to the Devil" - Crimesider - CBS News". 6 November 2012. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ See also (or, instead) this CBS News ("© 2010 CBS Interactive Inc.") web page: Smith, Ryan (January 13, 2010). "Pat Robertson: Haiti "Cursed" After "Pact to the Devil"". Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ KOSANBA.

- ^ a b "KOSANBA: A Scholarly Association for the Study of Haitian Vodou".

- ^ [1]

Sources

- Fernández Olmos, Margarite; Paravisini-Gebert, Lizabeth (2011). Creole Religions of the Caribbean: An Introduction from Vodou and Santería to Obeah and Espiritismo (second ed.). New York and London: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6228-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Johnson, Paul Christopher (2002). Secrets, Gossip, and Gods: The Transformation of Brazilian Candomblé. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195150582.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

References

- Alvarado, Denise (2011). The Voodoo Hoodoo Spellbook. Weiser Books. ISBN 978-1-57863-513-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blier, Suzanne Preston (1995). "Vodun: West African Roots of Vodou". In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. 61–87. ISBN 0-930741-47-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Karen McCarthy (1991). Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22475-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Karen McCarthy (1995). "Serving the Spirits: The Ritual Economy of Haitian Vodou". In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. 205–223. ISBN 0-930741-47-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - CIA World Factbook. "Haiti". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cosentino, Donald J. (1988). "More On Voodoo". African Arts. 21 (3 (May)): 77. JSTOR 3336454.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cosentino, Donald J. (1995b). "Introduction: Imagine Heaven". In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. 25–55. ISBN 0-930741-47-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cosentino, Henrietta B. (1995a). "The Sacred Arts of What? A Note on Orthography". In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. xiii–xiv. ISBN 0-930741-47-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Courlander, Harold (1988). "The Word Voodoo". African Arts. 21 (2 (February)): 88. doi:10.2307/3336535. JSTOR 3336535.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davis, Wade (1985). The Serpent and the Rainbow. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc. ISBN 0-671-50247-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davis, Wade (1988). Passage of Darkness: The Ethnobiology of the Haitian Zombie. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4210-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Desmangles, Leslie G. (1990). "The Maroon Republics and Religious Diversity in Colonial Haiti". Anthropos. 85 (4/6): 475–482. JSTOR 40463572.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fandrich, Ina J. (2007). "Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo". Journal of Black Studies. 37 (5 (May)): 775–791. doi:10.1177/0021934705280410. JSTOR 40034365.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lane, Maria J. (ed.) (1949). Funk & Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology, and Legend.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gordon, Leah (2000). The Book of Vodou. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0-7641-5249-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hurbon, Laënnec (1995). "American Fantasy and Haitian Vodou". In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. 181–197. ISBN 0-930741-47-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kilson, Martin; Rotberg, Robert I., eds. (1976). The African Diaspora: Interpretive Essays. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00779-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - KOSANBA. "KOSANBA: A Scholarly Association for the Study of Haitian Vodou". University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - LaMenfo, Mambo Vye Zo Komande (2011). Serving the Spirits. Charleston, SC: Create Space. ISBN 9781480086425.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Markel, Thylefors (2009). "'Our Government is in Bwa Kayiman:' a Vodou Ceremony in 1791 and its Contemporary Significations" (PDF). Stockholm Review of Latin American Studies (4 (March)): 73–84. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-22. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McAlister, Elizabeth (1993). "Sacred Stories from the Haitian Diaspora: A Collective Biography of Seven Vodou Priestesses in New York City". Journal of Caribbean Studies. 9 (1 & 2 (Winter)): 10–27. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moreau de Saint-Méry, Médéric Louis Élie (1797). Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de l'isle Saint-Domingue. Paris: Société des l'histoire des colonies françaises.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stevens-Arroyo, Anthony M. (2002). "The Contribution of Catholic Orthodoxy to Caribbean Syncretism". Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions. 19 (117 (January–March)): 37–58. doi:10.4000/assr.2477.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Robert Farris (1983). Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0-394-72369-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Valme, Jean M. (24 December 2010). "Officials: 45 people lynched in Haiti amid cholera fears". CNN. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Ajayi, Ade, J.F. & Espie, Ian, A Thousand Years of West African History, Great Britain, University of Ibadan, 1967.

- Alapini Julien, Le Petit Dahomeen, Grammaire. Vocabulaire, Lexique En Langue Du Dahomey, Avignon, Les Presses Universelles, 1955.

- Anderson, Jeffrey. 2005. Conjure In African American Society. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Angels in the Mirror: Vodou Musics of Haiti. Roslyn, New York: Ellipsis Arts. 1997. Compact Disc and small book.

- Argyle, W.J., The Fon of Dahomey: A History and Ethnography of the Old Kingdom, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Bellegarde-Smith and Claudine, Michel. Haitian Vodou: Spirit, Myth & Reality. Indiana University Press, 2006.

- Broussalis, Martín and Joseph Senatus Ti Wouj:"Voodoo percussion", 2007. A CD with text containing the ritual drumming.

- Chesi, Gert, Voodoo: Africa's Secret Power, Austria, Perliner, 1980.

- Chireau, Yvonne. 2003. Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Cosentino, Donald. 1995. "Imagine Heaven" in Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Edited by Cosentino, Donald et al. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Decalo, Samuel, Historical Dictionary of Dahomey, (People's Republic of Benin), N.J., The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1976.

- Deren, Maya, Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti (film). 1985 (Black and white documentary, 52 minutes).

- Deren, Maya, The Voodoo Gods. Thames & Hudson, 1953.

- Ellis, A.B., The Ewe Speaking Peoples of the Slave Coast of West Africa, Chicago, Benin Press Ldt, 1965.

- Fandrich, Ina J. 2005. The Mysterious Voodoo Queen, Marie Laveaux: A Study of Powerful Female Leadership in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans. New York: Routledge.

- Filan, Kinaz. The Haitian Vodou Handbook. Destiny Books (of Inner Traditions International), 2007.

- Herskovits, Melville J. (1971). Life in a Haitian Valley: Garden CITY, NEW YORK: DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC.

- Le Herisee, A. & Rivet, P., The Royanume d'Ardra et son evangelisation au XVIIIe siecle, Travaux et Memories de Institut d'Enthnologie, no. 7, Paris, 1929.

- Long, Carolyn. 2001. Spiritual Merchants: Magic, Religion and Commerce. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- McAlister, Elizabeth. 2002. Rara! Vodou, Power, and Performance in Haiti and its Diaspora. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- McAlister, Elizabeth. 1995. "A Sorcerer's Bottle: The Visual Art of Magic in Haiti". In Donald J. Cosentino, ed., Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. UCLA Fowler Museum, 1995.

- McAlister, Elizabeth. 2000 "Love, Sex, and Gender Embodied: The Spirits of Haitian Vodou." In J. Runzo and N. Martin, eds, Love, Sex, and Gender in the World Religions. Oxford: Oneworld Press.

- Malefijt, Annemarie de Waal (1989). Religion and Culture: An introduction to Anthropology of Religion. Long Groove, Illinois: Waveland Press, Inc.

- McAlister, Elizabeth. 1998. "The Madonna of 115th St. Revisited: Vodou and Haitian Catholicism in the Age of Transnationalism." In S. Warner, ed., Gatherings in Diaspora. Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press.

- Rhythms of Rapture: Sacred Musics of Haitian Vodou. Smithsonian Folkways, 1005. Compact Disc and Liner Notes

- Saint-Lot, Marie-José Alcide. 2003. Vodou: A Sacred Theatre. Coconut Grove: Educa Vision, Inc.

- Tallant, Robert. "Reference materials on voodoo, folklore, spirituals, etc. 6–1 to 6–5 -Published references on folklore and spiritualism." The Robert Tallant Papers. New Orleans Public Library. fiche 7 and 8, grids 1–22. Accessed 5 May 2005.

- Thornton, John K. 1988. "On the trail of Voodoo: African Christianity in Africa and the Americas" The Americas Vol: 44.3 Pp 261–278.

- Vanhee, Hein. 2002. "Central African Popular Christianity and the Making of Haitian Vodou Religion." in Central Africans and Cultural Transformations in the American Diaspora Edited by: L. M. Heywood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 243–64.

- Verger, Pierre Fátúmbí, Dieux d'Afrique: Culte des Orishas et Vodouns à l'ancienne Côte des Esclaves en Afrique et à Bahia, la Baie de Tous Les Saints au Brésil. 1954.

- Ward, Martha. 2004. Voodoo Queen: The Spirited Lives of Marie Laveau Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.

- Warren, Dennis, D., The Akan of Ghana, Accra, Pointer Limited, 1973. 9.

External links

- Haiti in Cuba: Vodou, Racism & Domination by Dimitri Prieto, Havana Times, June 8, 2009.

- Rara: Vodou, Power and Performance in Haiti and Its Diaspora.

- Voodoo Brings Solace To Grieving Haitians—All Things Considered from NPR. Audio and transcript. January 20, 2010.

- Living Vodou. Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Audio and transcript. February 4, 2010

- Voodoo Alive and Well in Haiti—slideshow by The First Post

- Inside Haitian Vodou—slideshow by Life