Melungeon: Difference between revisions

Sundayclose (talk | contribs) Reverted 1 edit by Fabrickator (talk): I'm not taking a position on this edit, but discussion has gone on just a few hours. Stop reverting and wait for consensus, or seek dispute resolution outlined in WP:DR. |

Zero evidence of any tribe claiming an individual has been presented in the article or the talk page. |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

On November 10, 1935, ''The Nevada State Journal'' wrote: "Melungeons are a distinct race of people living in the mountains of eastern Tennessee. They are about the color of mulattoes but have straight hair."<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.geocities.com/ourmelungeons/nevada.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091028085441/http://www.geocities.com/ourmelungeons/nevada.html |archive-date=October 28, 2009 |title=Melungeons |work=Nevada State Journal |date=November 10, 1935 |page=6}}</ref>{{better source needed|date=July 2023}} |

On November 10, 1935, ''The Nevada State Journal'' wrote: "Melungeons are a distinct race of people living in the mountains of eastern Tennessee. They are about the color of mulattoes but have straight hair."<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.geocities.com/ourmelungeons/nevada.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091028085441/http://www.geocities.com/ourmelungeons/nevada.html |archive-date=October 28, 2009 |title=Melungeons |work=Nevada State Journal |date=November 10, 1935 |page=6}}</ref>{{better source needed|date=July 2023}} |

||

In December 1943, Walter Ashby Plecker of Virginia sent county officials a letter warning against "colored" families trying to pass as "white" or "Indian" in violation of the [[Racial Integrity Act of 1924]]. He identified these as being "chiefly Tennessee Melungeons".<ref name="pleckerletter" /> He directed the offices to reclassify members of certain families as black, causing the loss for numerous families of documentation in records that showed their continued self-identification as being of [[Native American descent]].<ref name="pleckerletter"/><ref>{{cite book |last1=Schrift |first1=Melissa |title=Becoming Melungeon: Making an Ethnic Identity in the Appalachian South |date=2013 |publisher=[[University of Nebraska Press]] |isbn=978-0-8032-7154-8 |url=https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1185&context=unpresssamples |chapter=Introduction}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=The Racial Integrity Act, 1924: An Attack on Indigenous Identity |url=https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/racial-integrity-act.htm |website=[[National Park Service]] |access-date=25 August 2023 |date=June 21, 2023}}</ref> |

In December 1943, Walter Ashby Plecker of Virginia sent county officials a letter warning against "colored" families trying to pass as "white" or "Indian" in violation of the [[Racial Integrity Act of 1924]]. He identified these as being "chiefly Tennessee Melungeons".<ref name="pleckerletter" /> He directed the offices to reclassify members of certain families as black, causing the loss for numerous families of documentation in records that showed their continued self-identification as being of [[Native American descent]] on official forms.<ref name="pleckerletter"/><ref>{{cite book |last1=Schrift |first1=Melissa |title=Becoming Melungeon: Making an Ethnic Identity in the Appalachian South |date=2013 |publisher=[[University of Nebraska Press]] |isbn=978-0-8032-7154-8 |url=https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1185&context=unpresssamples |chapter=Introduction}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=The Racial Integrity Act, 1924: An Attack on Indigenous Identity |url=https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/racial-integrity-act.htm |website=[[National Park Service]] |access-date=25 August 2023 |date=June 21, 2023}}</ref> |

||

In the 20th century, during the [[Jim Crow]] era, some Melungeons attended boarding schools in [[Asheville, North Carolina]], [[Warren Wilson College]], and [[Dorland Institution]] which integrated earlier than other schools in the southern United States.<ref name=neal/> |

In the 20th century, during the [[Jim Crow]] era, some Melungeons attended boarding schools in [[Asheville, North Carolina]], [[Warren Wilson College]], and [[Dorland Institution]] which integrated earlier than other schools in the southern United States.<ref name=neal/> |

||

Revision as of 02:30, 27 August 2023

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

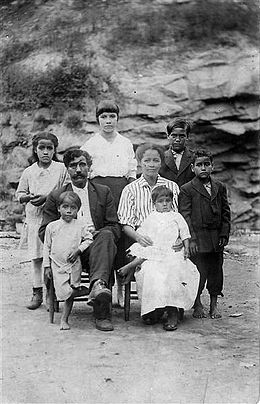

Goins family, Melungeons from Graysville, Tennessee, c. 1920s | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| United States (East Tennessee, Southwest Virginia,[1][2][3] and Kentucky[3]) | |

| Languages | |

| Appalachian English | |

| Religion | |

| Protestant Christianity (Baptist; Pentecostal)[citation needed] |

Melungeons (/məˈlʌndʒənz/ mə-LUN-jənz) (sometimes also spelled Malungeans, Melangeans, Melungeans, Melungins[4]) are a group of people from Appalachia who predominantly descend from Northern or Central European women and sub-Saharan African men.[2] Their ancestors were likely brought to Virginia as indentured servants in the mid-17th century.[2]

Initially, a generalized pejorative racial slur, Melungeon became associated with 40 families living in East Tennessee and Southwest Virginia.[1][2][3] Neighboring Melungeon settlements may have included the Cumberland Gap area of central Appalachia, which includes portions of eastern Kentucky.[3]

Unfounded theories of Melungeon origins that have been disproven include them having Portuguese, Native American, Turkish, or Romani ancestry.[3][2] They likely made these claims to account for their dark complexion while hiding their African heritage to remain free.[2]

Etymology

The term Melungeon likely comes from the French word mélange[3] ultimately derived from the Latin verb miscēre ("to mix, mingle, intermingle").[5] It is a derogatory term. The Tennessee Encyclopedia states that in the 19th century, "the word 'Melungeon' appears to have been used as an offensive term for nonwhite and/or low socioeconomic class persons by outsiders."[5]

The term Melungeon was historically considered an insult, a label applied to Appalachians who were by appearance or reputation of mixed-race ancestry. That term has never shed its pejorative character.[6] The spelling of the term varied widely, as was common for words and names at the time.

Early uses of term

The earliest historical record of the term Melungeon dates to 1813. In the minutes of the Stoney Creek Baptist Church in Scott County, Virginia, a woman stated another parishioner made the accusation that "she harbored them Melungins."[5]

The second oldest written use of the term was in 1840, when Tennessee politician described "an impudent Melungeon" from what became Washington, D.C., as being "a scoundrel who is half Negro and half Indian."[5]

In the 1890s, during the age of Yellow Journalism, the term "Melungeon" started to circulate and be reproduced in U.S. newspapers, when the journalist Will Allen Dromgoole wrote several articles on the Melungeons.[7]

In 1894, the US Department of the Interior, in its "Report of Indians Taxed and Not Taxed," under the section "Tennessee" noted: "In a number of states, small groups of people, preferring the freedom of the woods or the seashore to the confinement of labor in civilization, have become in some degree distinct from their neighbors, perpetrating their qualities and absorbing into their number those of like minded disposition, without preserving any clear racial lines. Such are the remnants called Indians in some states where pure-blooded Indian can hardly longer be found. In Tennessee there is such a group, popularly known as the Melungeans, in addition to those still known as Cherokees. The name seems to have been given to them by early French settlers, who recognized their mixed origin and applied to them the name of Malangeans or Malungeans, a corruption of the French word "melange" which means mixed. (See letter of Hamilton McMillan of North Carolina)"[4]

Through time the term has changed meanings but often referred to any mixed-race person and, at different times, has referred to 200 different communities across the Eastern United States.[2] These have included Van Guilders and Clappers of New York and Lumbees in North Carolina to Creoles in Louisiana.[2]

History

Melungeons migrated together, sometimes along with white neighbors, from western Virginia through the Piedmont frontier of North Carolina, before they settled primarily in the mountains of East Tennessee.[2]

Due to their mixed heritage in a segregated county, they were largely isolated.[3]

Mahala "Big Haley" Mullins was a famous moonshiner who was wanted by the law. She lived on the Newman Ridge overlooking the town of present-day Sneedville, Tennessee.[8]

On November 10, 1935, The Nevada State Journal wrote: "Melungeons are a distinct race of people living in the mountains of eastern Tennessee. They are about the color of mulattoes but have straight hair."[9][better source needed]

In December 1943, Walter Ashby Plecker of Virginia sent county officials a letter warning against "colored" families trying to pass as "white" or "Indian" in violation of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. He identified these as being "chiefly Tennessee Melungeons".[10] He directed the offices to reclassify members of certain families as black, causing the loss for numerous families of documentation in records that showed their continued self-identification as being of Native American descent on official forms.[10][11][12]

In the 20th century, during the Jim Crow era, some Melungeons attended boarding schools in Asheville, North Carolina, Warren Wilson College, and Dorland Institution which integrated earlier than other schools in the southern United States.[3]

Melungeon families

Definitions of who is Melungeon differ. Historians and genealogists have tried to identify surnames of different Melungeon families.[13][10] Virginia DeMarce listed Hale as a Melungeon surname.[14]

In 1943, Virginia State Registrar of Vital Statistics, Walter Ashby Plecker identified surnames by county: "Lee, Smyth and Wise: Collins, Gibson, (Gipson), Moore, Goins, Ramsey, Delph, Bunch, Freeman, Mise, Barlow, Bolden (Bolin), Mullins, Hawkins (chiefly Tennessee Melungeons)".[10]

Claims

The anthropologist E. Raymond Evans wrote in 1979 regarding Melungeons: "In Graysville, the Melungeons strongly deny their Black heritage and explain their genetic differences by claiming to have had Cherokee grandmothers. Many of the local whites also claim Cherokee ancestry and appear to accept the Melungeon claim. ..."[15]

In 1999, the historian C. S. Everett hypothesized that John Collins (recorded as a Sapony Indian who was expelled from Orange County, Virginia about January 1743), might be the same man as the Melungeon ancestor John Collins, who was classified as a "mulatto" in 1755 North Carolina records.[16] However, Everett revised that theory after he discovered evidence that these were two different men named John Collins. Only descendants of the latter man, who was identified as mulatto in the 1755 record in North Carolina, have any proven connection to the Melungeon families of eastern Tennessee.[17]

Jack D. Forbes speculated that the Melungeons may have been Saponi/Powhatan descendants, although he acknowledges an account from circa 1890 described them as being "free colored" and mulatto people.[18]

Genetic testing

From 2005 to 2011, researchers Roberta J. Estes, Jack H. Goins, Penny Ferguson, and Janet Lewis Crain began the Melungeon Core Y-DNA Group online. They interpreted these results in their (2011) paper titled "Melungeons, A Multi-Ethnic Population",[13] which shows that ancestry of the sample is primarily European and African, and one person having a Native American paternal haplotype.

Estes, Goins, Ferguson, and Crain wrote in their 2011 summary "Melungeons, A Multi-Ethnic Population" that the Riddle family is the only Melungeon participant with historical records identifying them as having Native American origins, but their DNA is European. Among the participants, only the Sizemore family is documented as having Native American DNA.[13]

In 2011, Estes, Goins, Ferguson, and Crain founded the Melungeon DNA Project. They reported that the Melungeon lines had likely originated in the unions of black and white indentured servants living in Virginia in the mid-17th century before slavery became widespread in the United States.[13] They concluded that as laws to prevent the mixing of races were put into place, those family groups intermarried with one another creating an endogamous group.[13]

Racial laws and court cases

Melungeon ancestors were considered by appearance to be mixed race. During the 18th and the early 19th centuries, census enumerators classified them as "mulatto," "other free," or as "free persons of color." Sometimes they were listed as "white" or sometimes as "black" or "negro," but almost never as "Indian".[citation needed] One family described as "Indian" was the Ridley (Riddle) family, as was noted on a 1767 Pittsylvania County, Virginia, tax list.[citation needed]

Ariela Gross referenced the 1846 State v. Solomon, Ezekial, Levi, Andrew, Wiatt, Vardy Collins, Zachariah, Lewis Minor, Hawkins County Circuit Court Minute Book, 1842-1848, Hawkins County Circuit Court, Hawkins County Courthouse box 31, 32 and the Jacob F. Perkins vs. John R. White, Carter County, July 1855 Abstract of depositions to support her conclusions made about identity and citizenship in 19th-century United States.[19]

In 1924, Virginia passed the Racial Integrity Act that codified hypodescent or the "one-drop rule,"[3] suggesting that anyone with any trace of African ancestry was legally Black and would fall under Jim Crow laws designed to limit the freedoms and rights of Black people.

Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States were not declared unconstitutional until the 1967 Loving v. Virginia case.[20]

Modern identity

By the mid-to-late 19th century, the term Melungeon appeared to have been used most frequently to refer to the biracial families of Hancock County and neighboring areas.[citation needed] Several other uses of the term in the print media, from the mid-19th to the early 20th centuries, have been collected by the Melungeon Heritage Association. The Melungeon Heritage Association represents the interests of Melungeon people today and holds annual conferences.[3]

Since the mid-1990s, popular interest in the Melungeons has grown tremendously, although many descendants have left the region of historical concentration. The writer Bill Bryson devoted the better part of a chapter to them in his The Lost Continent (1989).

People are increasingly self-identifying as having Melungeon ancestry.[21][page needed][better source needed]

Internet sites promote the anecdotal claim that Melungeons are more prone to certain diseases, such as sarcoidosis or familial Mediterranean fever. Academic medical centers have noted that neither of those diseases is confined to a single population.[22]

See also

- List of topics related to the African diaspora

- Vardy Community School

- Mulatto

- Pardo

- Dominickers in the Florida Panhandle

- Redbone (ethnicity)

- Turks of South Carolina

- Chestnut Ridge people of West Virginia

References

- ^ a b Holloway, Pippa (2008). Other Souths: Diversity and Difference in the U.S. South, Reconstruction to Present. Athens: University of Georgia Press. p. 201. ISBN 9780820330525.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Loller, Travis (11 March 2021). "'A whole lot of people upset by this study': DNA & the truth about Appalachia's Melungeons". News Leader. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Neal (June 24, 2015). "Melungeons explore mysterious mixed-race origins". USA Today. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ a b "1894 Report of the U.S. Department of the Interior, in its Report of Indians Taxed and Not Taxed" (PDF). www2.census.gov. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d Toplovich, Ann. "Melungeons". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Tennessee Historical Society. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Sovine, Melanie L. "The Mysterious Melungeons: a Critique of the Mythical Image." University of Kentucky Ph.D. dissertation, 1982

- ^ a b Pezzullo, Joanne (10 August 2017). "Calloway Collins". The Historical Melungeons. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Brown, Fred (March 15, 2009). "Sheriff keeps history alive, helps moonshiner stay sober". Knox News. USA Today. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "Melungeons". Nevada State Journal. November 10, 1935. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Plecker, Walter A. "Surnames, by Counties and Cities, of Mixed Negroid Virginia Families Striving to Pass as "Indian" or White". Encyclopedia Virginia: Virginia Humanities. Library of Virginia. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Schrift, Melissa (2013). "Introduction". Becoming Melungeon: Making an Ethnic Identity in the Appalachian South. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7154-8.

- ^ "The Racial Integrity Act, 1924: An Attack on Indigenous Identity". National Park Service. June 21, 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Estes, Roberta A.; Goins, Jack H.; Ferguson, Penny; Crain, Janet Lewis (Fall 2011). "Melungeons, A Multi-Ethnic Population" (PDF). Journal of Genetic Genealogy. 7 (1). Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ DeMarce, Virginia E. (1992). "Verry Slitly Mixt': Tri-Racial Isolate Families of the Upper South – A Genealogical Study", National Genealogical Society Quarterly 80 (March 1992): pp. 5–35, Historical-Melungeons

- ^ Evans, E. Raymond (1979). "The Graysville Melungeons: A Tri-racial People in Lower East Tennessee", Tennessee Anthropologist IV(1): 1–31.

- ^ C. S. Everett, "Melungeon History and Myth," Appalachian Journal (1999)

- ^ "Free African Americans, op.cit., Church and Cotanch Families". Freeafricanamericans.com. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Forbes, Jack D. (1993). Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252051005.

- ^ Gross, Ariela (2007). ""Of Portuguese Origin": Litigating Identity and Citizenship among the "Little Races" in Nineteenth-Century America". Law and History Review. 25 (3): 467–512. doi:10.1017/S0738248000004259. ISSN 0738-2480. JSTOR 27641498. S2CID 144084310.

- ^ "Loving v. Virginia". History Channel. 14 December 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ Kennedy, N. Brent; Kennedy, Robyn Vaughan (1997). The Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People: An Untold Story of Ethnic Cleansing in America (2nd ed.). Macon, GA: Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-516-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ ""Learning About Familial Mediterranean Fever", National Human Genome Research Institute". Genome.gov. November 17, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

Further reading

- Ball, Bonnie (1992). The Melungeons: Notes on the Origin of a Race' '. Johnson City, Tennessee: Overmountain Press.

- Berry, Brewton (1963). Almost White: A Study of Certain Racial Hybrids in the Eastern United States. New York: Macmillan Press.

- Bible, Jean Patterson (1975). Melungeons Yesterday and Today. Signal Mountain, Tennessee: Mountain Press.

- Brake, Katherine Vande. How They Shine: How They Shine: Melungeon Characters in Fiction of Appalachia. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Brake, Katherine Vande. Through the Back Door: Melungeon Literacies and Twenty-First Century Technologies. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Cavender, Anthony P. "The Melungeons of Upper East Tennessee: Persisting Social Identity," Tennessee Anthropologist 6 (1981): 27-36

- Goins, Jack H. (2000). Melungeons: And Other Pioneer Families, Blountville, Tennessee: Continuity Press.

- Hashaw, Tim. Children of Perdition: Melungeons and the Struggle of Mixed America. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Heinegg, Paul (2005). FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS OF VIRGINIA, NORTH CAROLINA, SOUTH CAROLINA, MARYLAND AND DELAWARE Including the family histories of more than 80% of those counted as "all other free persons" in the 1790 and 1800 census, Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing, 1999–2005. Available in its entirety online.

- Hirschman, Elizabeth. Melungeons: The Last Lost Tribe in America. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Johnson, Mattie Ruth (1997). My Melungeon Heritage: A Story of Life on Newman's Ridge. Johnson City, Tennessee: Overmountain Press.

- Kennedy, N. Brent (1997) The Melungeons: the resurrection of a proud people. Mercer University Press.

- Kessler, John S. and Donald Ball. North From the Mountains: A Folk History of the Carmel Melungeon Settlement, Highland County, Ohio. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Langdon, Barbara Tracy (1998). The Melungeons: An Annotated Bibliography: References in both Fiction and Nonfiction, Hemphill, Texas: Dogwood Press.

- Lister, Richard (July 3, 2009). "Lost people of Appalachia". BBC News Online.

- McGowan, Kathleen (2003). "Where do we really come from?", DISCOVER 24 (5, May 2003)

- Offutt, Chris. (1999) "Melungeons", in Out of the Woods, Simon & Schuster.

- Overbay, DruAnna Williams. Windows on the Past: The Cultural Heritage of Vardy, Hancock County, Tennessee. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Podber, Jacob. The Electronic Front Porch: An Oral History of the Arrival of Modern Media in Rural Appalachia and the Melungeon Community. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Price, Henry R. (1966). "Melungeons: The Vanishing Colony of Newman's Ridge." Conference paper. American Studies Association of Kentucky and Tennessee. March 25–26, 1966.

- Reed, John Shelton (1997). "Mixing in the Mountains", Southern Cultures 3 (Winter 1997): 25–36.(subscription required)

- Scolnick, Joseph M Jr. and N. Brent Kennedy. (2004). From Anatolia to Appalachia: A Turkish American Dialogue. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Vande Brake, Katherine (2001). How They Shine: Melungeon Characters in the Fiction of Appalachia, Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press.

- Williamson, Joel (1980). New People: Miscegenation and Mulattoes in the United States, New York: Free Press.

- Winkler, Wayne. 2019. Beyond the sunset: The Melungeon drama, 1969-1976. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Winkler, Wayne (2004). "Walking Toward the Sunset: The Melungeons of Appalachia", Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press.

- Winkler, Wayne and Estes, Roberta (7/11/2012). "For Some People of Appalachia complicated roots", Tell Me More. National Public Radio. npr.org accessed 12 June 2023

External links

- Melungeon Heritage Association

- Mixed Race Studies

- Paul Brodwin, ""Bioethics in action" and human population genetics researMacon, GA: Mercer University Press.ch", Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, Volume 29, Number 2 (2005), 145-178, DOI: 10.1007/s11013-005-7423-2 PDF, addresses issue of 2002 Melungeon DNA study by Kevin Jones, which is unpublished

- Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, 1999–2005

- "Melungeons", Digital Library of Appalachia. Contains numerous photographs and documents related to Melungeons, mostly from 1900 to 1950.

- A Mystery People: The Melungeons From Louis Gates Jr's "Finding your Roots."