Dextroamphetamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dexedrine, Dextrostat, Dexamphetamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605027 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Moderate to High |

| Routes of administration | Oral (only medically-utilized route) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral 75–100%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic: CYP2D6,[6] DBH,[7] and FMO[8] |

| Elimination half-life | 10-12 hours[3][4] |

| Excretion | Renal (45%);[5] urinary pH-dependent |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.103 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H13N |

| Molar mass | 135.20622 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 0.913 g/cm3 |

| Boiling point | 201.5 °C (394.7 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 20 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

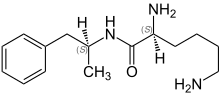

Dextroamphetamine (USAN), Dexamphetamine (AAN)[9][10] and Dexamfetamine (INN and BAN) is a potent psychostimulant and amphetamine stereoisomer prescribed for the treatment of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adults as well as for a sleep disorder known as narcolepsy. Dextroamphetamine is also widely used by military air forces as a 'go-pill' during fatigue-inducing mission profiles such as night-time bombing missions.

The amphetamine molecule has two stereoisomers: levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine. Dextroamphetamine is the dextrorotatory, or "right-handed", enantiomer of the amphetamine molecule. Dextroamphetamine is available as a generic drug or under several brand names, including Dexedrine and Dextrostat, Dexamphetamine. Dextroamphetamine is also an active metabolite of the prodrug Vyvanse.

Uses

Medical

Dextroamphetamine is used for the treatment of ADHD and narcolepsy.[11] Dextroamphetamine may be used under circumstances other than (indicated) for off-label use in the following conditions:

- Depression

- Autism

- Fragile X syndrome

- Developmental disabilities

- Stroke recovery

Investigational uses

Though such use remains out of the mainstream, dextroamphetamine has been successfully applied in the treatment of certain categories of depression as well as other psychiatric syndromes.[12] Such alternate uses include reduction of fatigue in cancer patients,[13] antidepressant treatment for HIV patients with depression and debilitating fatigue,[14] and early-stage physiotherapy for severe stroke victims.[15] If physical therapy patients take dextroamphetamine while they practice their movements for rehabilitation, they may learn to move much faster than without dextroamphetamine, and in practice sessions with shorter lengths.[16]

Contraindications

- Glaucoma

- Moderate-severe hypertension

- Hyperthyroidism

- Epilepsy

- Phaeochromocytoma

- Tourette syndrome

- Psychomotor agitation

- Advanced arteriosclerosis

- Ischaemic heart disease

- Angina pectoris

- Hypersensitivity or idiosyncrasy to the sympathomimetic amines

- During or within 14 days following the administration of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (hypertensive crisis may occur)[3][17][18][19]

Side effects

By frequency[3][17][18][20][21][22]

Very common (>10% frequency)

- Appetite loss

- Insomnia

- Abdominal pain

Common (1-10% frequency)

- High heart rate

- Palpitations

- Tremors

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Weight loss

- Dry mouth

- Diarrhea

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Infection

- Nausea/vomiting

- Dyspepsia (indigestion)

- Nervousness

- Emotional lability

Unknown frequency adverse effects

- Urticaria

- Sexual dysfunction

- Overstimulation

- Restlessness

- Dyskinesia

- Tremor

- Exacerbation of motor and phonic tics and Tourette’s syndrome

- Hyperactivity

Serious adverse effects

- Seizures

- Growth stunting

- Hypertension

- Stroke

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Psychosis which can occur at therapeutic doses after chronic treatment.

- Mania/Hypomania

- Drug dependence

- Raynaud's phenomenon

- Cardiomyopathy

Recent studies by the FDA indicate that, in children, young adults, and adults, there is no association between serious adverse cardiovascular events (sudden death, myocardial infarction, and stroke) and the use of dextroamphetamine or other ADHD stimulants in individuals with normal cardiovascular function.[23][24][25]

Overdosage

An amphetamine overdose is rarely fatal with appropriate care.[26] It can lead to different symptoms.[27][27][28] A moderate overdose may induce symptoms including irregular heartbeat, confusion, painful urination, high or low blood pressure, hyperthermia, hyperreflexia, muscle pain, severe agitation, rapid breathing, tremor, urinary hesitancy, and urinary retention.[27][28][29] An extremely large overdose may produce symptoms such as adrenergic storm, amphetamine psychosis, anuria, cardiogenic shock, cerebral hemorrhage, circulatory collapse, edema (peripheral or pulmonary), extreme fever, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, rapid muscle breakdown, serotonin toxidrome, and stereotypy.[ref-note 1] Fatal amphetamine poisoning usually also involves convulsions and coma.[27][29]

Psychosis

Abuse of amphetamines can result in a stimulant psychosis which may present with a variety of symptoms (e.g. paranoia, hallucinations, delusions). A Cochrane Collaboration review on treatment for amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methamphetamine induced psychosis[33] states that about 5-15% of users fail to recover completely.[34] The same review asserts that, based upon at least one trial, antipsychotic medications effectively resolve the symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.[33] An amphetamine psychosis may also develop occasionally as a treatment-emergent side effect.[35][35][36]

Withdrawal

While addiction is a serious risk with heavy recreational amphetamine use, it is unlikely to arise from typical medical use.[27][29][37] Tolerance is developed rapidly in amphetamine abuse; therefore, periods of extended use require increasing amounts of the drug in order to achieve the same effect.[38] According to a Cochrane Collaboration review on withdrawal in highly dependent amphetamine and methamphetamine abusers, "when chronic heavy users abruptly discontinue amphetamine use, many report a time-limited withdrawal syndrome that occurs within 24 hours of their last dose."[39] This review noted that withdrawal symptoms in chronic, high-dose users are frequent, occurring in up to 87.6% of cases, and persist for 3–4 weeks with a marked "crash" phase occurring during the first week.[39] Amphetamine withdrawal symptoms can include fatigue, dysphoric mood, increased appetite, vivid or lucid dreams, hypersomnia or insomnia, increased movement or decreased movement, anxiety, and drug craving.[39] The review suggested that withdrawal symptoms are associated with the degree of dependence, suggesting that therapeutic use would result in far milder discontinuation symptoms.[39] The USFDA does not indicate the presence of withdrawal symptoms following discontinuation of pharmaceutical amphetamine use after an extended period at therapeutic doses.[40][41][42]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

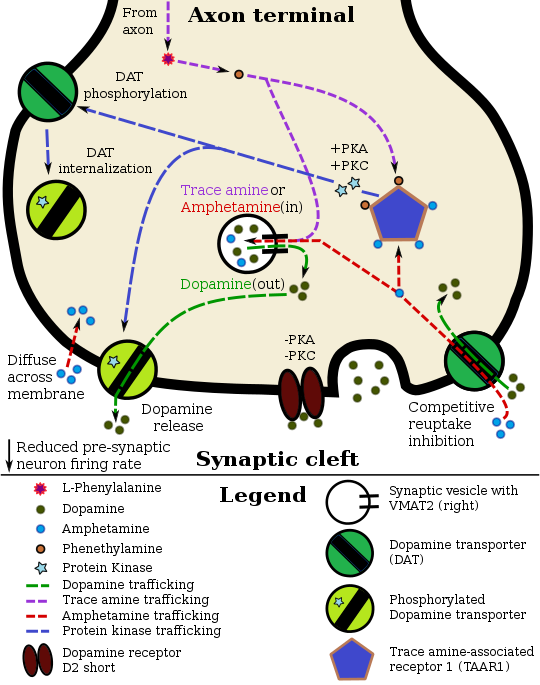

Pharmacodynamics of amphetamine in a dopamine neuron

|

Amphetamine and its enantiomers have been identified as potent full agonists of trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1), a GPCR, discovered in 2001, that is important for regulation of monoaminergic systems in the brain.[50][51] Activation of TAAR1 increases cAMP production via adenylyl cyclase activation and inhibits the function of the dopamine transporter, norepinephrine transporter, and serotonin transporter, as well as inducing the release of these monoamine neurotransmitters (effluxion).[50][52][43] Amphetamine enantiomers are also substrates for a specific neuronal synaptic vesicle uptake transporter called VMAT2.[44] When amphetamine is taken up by VMAT2, the vesicle releases (effluxes) dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, among other monoamines, into the cytosol in exchange.[44]

Dextroamphetamine (the dextrorotary enantiomer) and levoamphetamine (the levorotary enantiomer) have identical pharmacodynamics, but their binding affinities to their biomolecular targets vary.[29][51] Dextroamphetamine is a more potent agonist of TAAR1 than levoamphetamine.[51] Consequently, dextroamphetamine produces roughly three to four times more central nervous system (CNS) stimulation than levoamphetamine;[29][51] however, levoamphetamine has slightly greater cardiovascular and peripheral effects.[29]

Related endogenous compounds

Amphetamine has a very similar structure and function to the endogenous trace amines, which are naturally occurring molecules produced in the human body and brain.[43][53] Among this group, the most closely related compounds are phenethylamine, the parent compound of amphetamine, and N-methylphenethylamine, an isomer of amphetamine (i.e., identical molecular formula).[43][53] In humans, phenethylamine is produced in the body directly from phenylalanine by the same enzyme that converts L-DOPA into dopamine, aromatic amino acid decarboxylase.[53] In turn, N‑methylphenethylamine is metabolized from phenethylamine by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase, which the same enzyme that metabolizes norepinephrine into adrenaline.[53] Like amphetamine, both phenethylamine and N‑methylphenethylamine regulate monoamine neurotransmission via TAAR1;[43] however, unlike amphetamine, both of these substances are broken down by monoamine oxidase, and therefore have a shorter half-life than amphetamine.[53]

Pharmacokinetics

Amphetamine is well absorbed from the gut, and bioavailability is typically over 75% for dextroamphetamine.[54] However, oral availability varies with gastrointestinal pH.[55] Dextroamphetamine is a weak base with a pKa of 9–10;[6] consequently, when the pH is basic, more of the drug is in its lipid soluble free base form, and more is absorbed through the lipid-rich cell membranes of the gut epithelium.[6][55] Conversely, an acidic pH means the drug is predominantly in its water soluble cationic form, and less is absorbed.[6][55]

Approximately 15–40% of dextroamphetamine circulating in the bloodstream is bound to plasma proteins.[56]

The half-life of dextroamphetamine varies with urine pH.[6] At normal urine pH, the half-life of dextroamphetamine is 9–11 hours.[6] An acidic diet will reduce the half-life to 8–11 hours, while an alkaline diet will increase the range to 16–31 hours.[57][58] The immediate-release and extended release variants of dextroamphetamine salts reach peak plasma concentrations at 3 hours and 7 hours post-dose respectively.[6] Dextromphetamine is eliminated via the kidneys, with 30–40% of the drug being excreted unchanged at normal urinary pH.[6] When the urinary pH is basic, more of the drug is in its poorly water soluble free base form, and less is excreted.[6] When urine pH is abnormal, the urinary recovery of amphetamine may range from a low of 1% to as much as 75%, depending mostly upon whether urine is too basic or acidic, respectively.[6] Amphetamine is usually eliminated within two days of the last oral dose.[57] Apparent half-life and duration of effect increase with repeated use and accumulation of the drug.[59]

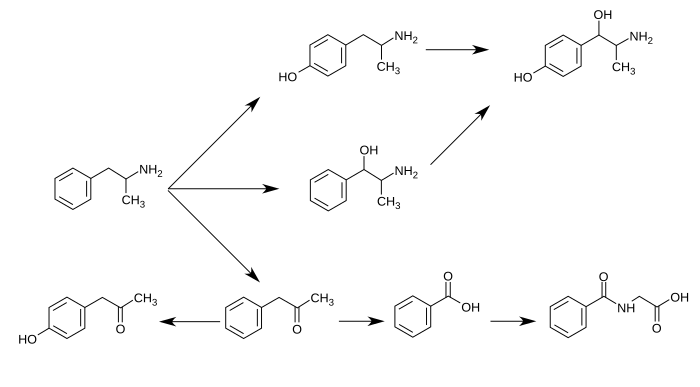

CYP2D6, Dopamine β-hydroxylase, and flavin-containing monooxygenase are the only enzymes currently known to metabolize amphetamine in humans.[6][7][8][60] Amphetamine has a variety of excreted metabolic products, including 4-hydroxyamfetamine, 4-hydroxynorephedrine, 4-hydroxyphenylacetone, benzoic acid, hippuric acid, norephedrine, and phenylacetone.[6][57][61] Among these metabolites, the active sympathomimetics are 4‑hydroxyamphetamine,[62] 4‑hydroxynorephedrine,[63] and norephedrine.[64]

The main metabolic pathways involve aromatic para-hydroxylation, aliphatic alpha- and beta-hydroxylation, N-oxidation, N-dealkylation, and deamination.[6][57] The known pathways include:[6][8][61]

Metabolic pathways of amphetamine in humans[sources 1]

|

History, society, and culture

Racemic amphetamine was first synthesized under the chemical name "phenylisopropylamine" in Berlin, 1887 by the Romanian chemist Lazar Edeleanu.[73] It was not widely marketed until 1932, when the pharmaceutical company Smith, Kline & French (now known as GlaxoSmithKline) introduced it in the form of the Benzedrine inhaler for use as a bronchodilator. Notably, the amphetamine contained in the Benzedrine inhaler was the liquid free-base,[n 1] not a chloride or sulfate salt.

Three years later, in 1935, the medical community became aware of the stimulant properties of amphetamine, specifically dexamfetamine, and in 1937 Smith, Kline, and French introduced tablets under the tradename Dexedrine.[74] In the United States, Dexedrine was approved to treat narcolepsy, attention disorders, depression, and obesity. In Canada, epilepsy and parkinsonism were also approved indications.[75] Dexamfetamine was marketed in various other forms in the following decades, primarily by Smith, Kline, and French, such as several combination medications including a mixture of dexamfetamine and amobarbital (a barbiturate) sold under the tradename Dexamyl and, in the 1950s, an extended release capsule (the "Spansule").[76]

It quickly became apparent that dexamfetamine and other amphetamines had a high potential for misuse, although they were not heavily controlled until 1970, when the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act was passed by the United States Congress. Dexamfetamine, along with other sympathomimetics, was eventually classified as Schedule II, the most restrictive category possible for a drug with a government-sanctioned, recognized medical use.[77] Internationally, it has been available under the names AmfeDyn (Italy), Curban (US), Obetrol (Switzerland), Simpamina (Italy), Dexedrine/GSK (US & Canada), Dexedrine/UCB (United Kingdom), Dextropa (Portugal), and Stild (Spain).[78]

In October 2010, GlaxoSmithKline sold the rights for Dexedrine Spansule to Amedra Pharmaceuticals (a subsidiary of CorePharma).[79]

The U.S. Air Force uses dexamfetamine as one of its "go pills", given to pilots on long missions to help them remain focused and alert. Conversely, "no-go pills" are used after the mission is completed, to combat the affects of the mission and "go-pills".[80][81][82][83] The Tarnak Farm incident was linked by media reports to the use of this drug on long term fatigued pilots. The military did not accept this explanation, citing the lack of similar incidents. Newer stimulant medications or awakeness promoting agents with different side effect profiles, such as modafinil, are being investigated and sometimes issued for this reason.[81]

Formulations

| Brand name |

United States Adopted Name |

(D:L) ratio of salts |

Dosage form |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adderall | – | 3:1 | tablet | [84][85] |

| Adderall XR | – | 3:1 | capsule | [84][85] |

| Dexedrine | dextroamphetamine sulfate | 1:0 | capsule | [84] |

| ProCentra | dextroamphetamine sulfate | 1:0 | tablet | [84] |

| Vyvanse | lisdexamfetamine dimesylate | 1:0 | capsule | [86] |

| Zenzedi | dextroamphetamine sulfate | 1:0 | liquid | [84] |

Dextroamphetamine sulfate

In the United States, an instant-release (IR) tablet preparation of the salt dexamfetamine sulfate is approved under the brand names Dexedrine and Dextrostat, in 5 mg and 10 mg strengths,[citation needed] and generic formulations from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries and recently Wilshire Pharmaceuticals. It is also available as a capsule preparation of controlled-release (CR) dexamfetamine sulfate, under the brand names Dexedrine SR and Dexedrine Spansule, in the strengths of 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg. A bubblegum flavored oral solution is available under the brand name ProCentra, manufactured by FSC Pediatrics, which is designed to be an easier method of administration in children who have difficulty swallowing tablets, each 5 mL contains 5 mg dexamfetamine.[87]

In Australia, dexamfetamine is available in bottles of 100 instant release 5 mg tablets as a generic drug.[88] or slow release dexamfetamine preparations may be compounded by individual chemists.[89] Similarly, in the United Kingdom it is only available in 5 mg instant release sulfate tablets under the generic name dexamfetamine sulphate having had been available under the brand name Dexedrine prior to UCB Pharma disinvesting the product to another pharmaceutical company (Auden Mckenzie).[90]

Lisdexamfetamine

Dexamfetamine is the active metabolite of the prodrug lisdexamfetamine (L-lysine-dextroamphetamine), available by the brand name Vyvanse (Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate). Lisdexamfetamine is metabolised in the gastrointestinal tract, while dextroamphetamine's metabolism is hepatic.[91] Lisdexamfetamine is therefore an inactive compound until it is converted into an active compound by the digestive system. Vyvanse is marketed as once-a-day dosing as it provides a slow release of dexamfetamine into the body. Vyvanse is available as capsules, and in six strengths; 20 mg, 30 mg, 40 mg, 50 mg, 60 mg, and 70 mg. The conversion rate of Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate to dextroamphetamine base is 0.2948,[92] thus a 30 mg-strength Vyvanse capsule is molecularly equivalent to 8.844 mg dexamfetamine base.

Adderall

Another pharmaceutical that contains dextroamphetamine is Adderall. The drug formulation of Adderall, including both the immediate release (IR) and extended release (XR) forms, is:

- One-quarter racemic (d,l-)amphetamine aspartate monohydrate

- One-quarter dextroamphetamine saccharate

- One-quarter dextroamphetamine sulfate

- One-quarter racemic (d,l-)amphetamine sulfate

The salt ratio, as noted above, is 75%:25% i.e. 3:1 dextroamphetamine-salts to levoamphetamine-salts. The active ingredients are 72.7% dextroamphetamine-base and levoamphetamine-base (the remaining percentage).

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Dextromphetamine". DrugBank. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "Dexedrine Medication Guide" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. May 2013. p. 1. Retrieved 2 November 2013. Cite error: The named reference "TGA" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Dextroamphetamine Sulfate (dextroamphetamine sulfate) Tablet [ETHEX Corporation]". DailyMed. ETHEX Corporation. February 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ "dextrostat (dextroamphetamine sulfate) tablet [Shire US Inc.]". DailyMed. Wayne, PA: Shire US Inc. August 2006. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 30 December 2013. Cite error: The named reference "FDA Pharmacokinetics" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (2013). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry (7th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 648. ISBN 1609133455.

Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Krueger SK, Williams DE (June 2005). "Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism". Pharmacol. Ther. 106 (3): 357–387. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001. PMC 1828602. PMID 15922018. Cite error: The named reference "FMO" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Template:Cite isbn

- ^ Template:Cite isbn

- ^ First line treatments U.S. Food and Drug Administration | GlaxoSmithKline Prescribing Information

- ^ Warneke L (1990). "Psychostimulants in psychiatry". Can J Psychiatry. 35 (1): 3–10. PMID 2180548.

- ^ Breitbart W, Alici Y (2010). "Psychostimulants for cancer-related fatigue". J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 8 (8): 933–42. PMID 20870637.

- ^ Wagner G, Rabkin R (2000). "Effects of dextroamphetamine on depression and fatigue in men with HIV: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 (6): 436–40. doi:10.4088/JCP.v61n0608. PMID 10901342.

- ^ Martinsson L, Yang X, Beck O, Wahlgren N, Eksborg S (2003). "Pharmacokinetics of dextroamphetamine in acute stroke". Clin Neuropharmacol. 26 (5): 270–6. doi:10.1097/00002826-200309000-00012. PMID 14520168.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Butefisch CM; et al. (2002). "Modulation of Use-Dependent Plasticity by D-Amphetamine". Annals of Neurology. 51 (1): 59–68. doi:10.1002/ana.10056. PMID 11782985.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c "DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE tablet [Barr Laboratories Inc.]". DailyMed. Barr Laboratories Inc. October 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "dextroamphetamine (Rx) - Dexedrine, Liquadd, more..." Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ RxList | Dexedrine (Dextroamphetamine)

- ^ Vitiello B (2008). "Understanding the risk of using medications for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with respect to physical growth and cardiovascular function". Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 17 (2): 459–74, xi. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.010. PMC 2408826. PMID 18295156.

- ^ Dextroamphetamine (Oral Route) | MayoClinic.com

- ^ Vitiello B (2008). "Understanding the Risk of Using Medications for ADHD with Respect to Physical Growth and Cardiovascular Function". Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 17 (2): 459–74, xi. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.010. PMC 2408826. PMID 18295156.

- ^ "ADHD Medications and Risk of Stroke In Young and Middle-Aged Adults" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "ADHD Medications and Risk of Serious Coronary Heart Disease in Young and Middle-Aged Adults" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Medications and Risk of Serious Cardiovascular Disease in Children and Youth" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b Spiller HA, Hays HL, Aleguas A (June 2013). "Overdose of drugs for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: clinical presentation, mechanisms of toxicity, and management". CNS Drugs. 27 (7): 531–543. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0084-8. PMID 23757186.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. June 2013. p. 11. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ a b c "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. June 2013. pp. 4–8. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Westfall DP, Westfall TC (2010). "Miscellaneous Sympathomimetic Agonists". In Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC (ed.). Goodman & Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071624428.

{{cite book}}: External link in|sectionurl=|sectionurl=ignored (|section-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ O'Connor PG (February 2012). "Amphetamines". Merck Manual for Health Care Professionals. Merck. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Albertson TE (2011). "Amphetamines". In Olson KR, Anderson IB, Benowitz NL, Blanc PD, Kearney TE, Kim-Katz SY, Wu AHB (ed.). Poisoning & Drug Overdose (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 77–79. ISBN 9780071668330.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Oskie SM, Rhee JW (11 February 2011). "Amphetamine Poisoning". Emergency Central. Unbound Medicine. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Ling W (2009). "Treatment for amphetamine psychosis (Review)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hofmann FG. A handbook on drug and alcohol abuse: the biomedical aspects. 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- ^ a b Berman, SM.; Kuczenski, R.; McCracken, JT.; London, ED. (February 2009). "Potential adverse effects of amphetamine treatment on brain and behavior: a review". Mol Psychiatry. 14 (2): 123–42. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.90. PMC 2670101. PMID 18698321. Cite error: The named reference "Berman-2009" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ . Merck Sharpe and Dohme http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec15/ch198/ch198k.htmlAmphetamines. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stolerman IP (2010). Stolerman IP (ed.). Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology. Berlin; London: Springer. p. 78. ISBN 9783540686989.

Although [substituted amphetamines] are also used as recreational drugs, with important neurotoxic consequences when abused, addiction is not a high risk when therapeutic doses are used as directed.

- ^ "Amphetamines: Drug Use and Abuse". Merck Manual Home Edition. Merck. February 2003. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- ^ a b c d Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Heinzerling K, Ling W (2009). Shoptaw SJ (ed.). "Treatment for amphetamine withdrawal". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2): CD003021. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003021.pub2. PMID 19370579.

The prevalence of this withdrawal syndrome is extremely common (Cantwell 1998; Gossop 1982) with 87.6% of 647 individuals with amphetamine dependence reporting six or more signs of amphetamine withdrawal listed in the DSM when the drug is not available (Schuckit 1999)...Withdrawal symptoms typically present within 24 hours of the last use of amphetamine, with a withdrawal syndrome involving two general phases that can last 3 weeks or more. The first phase of this syndrome is the initial "crash" that resolves within about a week (Gossop 1982;McGregor 2005)...{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Adderall IR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. March 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ "Dexedrine Medication Guide" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. May 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. June 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–76. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b c d Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216: 86–98. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMID 21272013.

- ^ Sulzer D, Cragg SJ, Rice ME (August 2016). "Striatal dopamine neurotransmission: regulation of release and uptake". Basal Ganglia. 6 (3): 123–148. doi:10.1016/j.baga.2016.02.001. PMC 4850498. PMID 27141430.

Despite the challenges in determining synaptic vesicle pH, the proton gradient across the vesicle membrane is of fundamental importance for its function. Exposure of isolated catecholamine vesicles to protonophores collapses the pH gradient and rapidly redistributes transmitter from inside to outside the vesicle. ... Amphetamine and its derivatives like methamphetamine are weak base compounds that are the only widely used class of drugs known to elicit transmitter release by a non-exocytic mechanism. As substrates for both DAT and VMAT, amphetamines can be taken up to the cytosol and then sequestered in vesicles, where they act to collapse the vesicular pH gradient.

- ^ Ledonne A, Berretta N, Davoli A, Rizzo GR, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB (July 2011). "Electrophysiological effects of trace amines on mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons". Front. Syst. Neurosci. 5: 56. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2011.00056. PMC 3131148. PMID 21772817.

Three important new aspects of TAs action have recently emerged: (a) inhibition of firing due to increased release of dopamine; (b) reduction of D2 and GABAB receptor-mediated inhibitory responses (excitatory effects due to disinhibition); and (c) a direct TA1 receptor-mediated activation of GIRK channels which produce cell membrane hyperpolarization.

- ^ "TAAR1". GenAtlas. University of Paris. 28 January 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

• tonically activates inwardly rectifying K(+) channels, which reduces the basal firing frequency of dopamine (DA) neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA)

- ^ Underhill SM, Wheeler DS, Li M, Watts SD, Ingram SL, Amara SG (July 2014). "Amphetamine modulates excitatory neurotransmission through endocytosis of the glutamate transporter EAAT3 in dopamine neurons". Neuron. 83 (2): 404–416. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.043. PMC 4159050. PMID 25033183.

AMPH also increases intracellular calcium (Gnegy et al., 2004) that is associated with calmodulin/CamKII activation (Wei et al., 2007) and modulation and trafficking of the DAT (Fog et al., 2006; Sakrikar et al., 2012). ... For example, AMPH increases extracellular glutamate in various brain regions including the striatum, VTA and NAc (Del Arco et al., 1999; Kim et al., 1981; Mora and Porras, 1993; Xue et al., 1996), but it has not been established whether this change can be explained by increased synaptic release or by reduced clearance of glutamate. ... DHK-sensitive, EAAT2 uptake was not altered by AMPH (Figure 1A). The remaining glutamate transport in these midbrain cultures is likely mediated by EAAT3 and this component was significantly decreased by AMPH

- ^ Vaughan RA, Foster JD (September 2013). "Mechanisms of dopamine transporter regulation in normal and disease states". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34 (9): 489–496. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.07.005. PMC 3831354. PMID 23968642.

AMPH and METH also stimulate DA efflux, which is thought to be a crucial element in their addictive properties [80], although the mechanisms do not appear to be identical for each drug [81]. These processes are PKCβ– and CaMK–dependent [72, 82], and PKCβ knock-out mice display decreased AMPH-induced efflux that correlates with reduced AMPH-induced locomotion [72].

- ^ a b Bunzow JR, Sonders MS, Arttamangkul S, Harrison LM, Zhang G, Quigley DI, Darland T, Suchland KL, Pasumamula S, Kennedy JL, Olson SB, Magenis RE, Amara SG, Grandy DK (December 2001). "Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor". Mol. Pharmacol. 60 (6): 1181–8. doi:10.1124/mol.60.6.1181. PMID 11723224.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Lewin AH, Miller GM, Gilmour B (December 2011). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 is a stereoselective binding site for compounds in the amphetamine class". Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19 (23): 7044–7048. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.007. PMC 3236098. PMID 22037049.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Borowsky B, Adham N, Jones KA, Raddatz R, Artymyshyn R, Ogozalek KL, Durkin MM, Lakhlani PP, Bonini JA, Pathirana S, Boyle N, Pu X, Kouranova E, Lichtblau H, Ochoa FY, Branchek TA, Gerald C (July 2001). "Trace amines: identification of a family of mammalian G protein-coupled receptors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (16): 8966–71. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.8966B. doi:10.1073/pnas.151105198. PMC 55357. PMID 11459929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacol. Ther. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

Fig. 2. Synthetic and metabolic pathways for endogenous and exogenously administered trace amines and sympathomimetic amines...

Trace amines are metabolized in the mammalian body via monoamine oxidase (MAO; EC 1.4.3.4) (Berry, 2004) (Fig. 2)...It deaminates primary and secondary amines that are free in the neuronal cytoplasm but not those bound in storage vesicles of the sympathetic neurone...

Thus, MAO inhibitors potentiate the peripheral effects of indirectly acting sympathomimetic amines. It is not often realized, however, that this potentiation occurs irrespective of whether the amine is a substrate for MAO. An α-methyl group on the side chain, as in amphetamine and ephedrine, renders the amine immune to deamination so that they are not metabolized in the gut. Similarly, β-PEA would not be deaminated in the gut as it is a selective substrate for MAO-B which is not found in the gut...

Brain levels of endogenous trace amines are several hundred-fold below those for the classical neurotransmitters noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin but their rates of synthesis are equivalent to those of noradrenaline and dopamine and they have a very rapid turnover rate (Berry, 2004). Endogenous extracellular tissue levels of trace amines measured in the brain are in the low nanomolar range. These low concentrations arise because of their very short half-life,... - ^ "Dextroamphetamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013. pp. 8–10. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Amphetamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "Amphetamine". Pubchem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ "AMPHETAMINE". United States National Library of Medicine - Toxnet. Hazardous Substances Data Bank. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

Concentrations of (14)C-amphetamine declined less rapidly in the plasma of human subjects maintained on an alkaline diet (urinary pH > 7.5) than those on an acid diet (urinary pH < 6). Plasma half-lives of amphetamine ranged between 16-31 hr & 8-11 hr, respectively, & the excretion of (14)C in 24 hr urine was 45 & 70%.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ Richard RA (1999). "Chapter 5—Medical Aspects of Stimulant Use Disorders". National Center for Biotechnology Information Bookshelf. Treatment Improvement Protocol 33. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ "Amphetamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Santagati NA, Ferrara G, Marrazzo A, Ronsisvalle G (September 2002). "Simultaneous determination of amphetamine and one of its metabolites by HPLC with electrochemical detection". J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 30 (2): 247–255. doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00330-8. PMID 12191709.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Metabolites" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "p-Hydroxyamphetamine". PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ "p-Hydroxynorephedrine". PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ "Phenylpropanolamine". PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b Glennon RA (2013). "Phenylisopropylamine stimulants: amphetamine-related agents". In Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (eds.). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (7th ed.). Philadelphia, US: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 646–648. ISBN 9781609133450.

The simplest unsubstituted phenylisopropylamine, 1-phenyl-2-aminopropane, or amphetamine, serves as a common structural template for hallucinogens and psychostimulants. Amphetamine produces central stimulant, anorectic, and sympathomimetic actions, and it is the prototype member of this class (39). ... The phase 1 metabolism of amphetamine analogs is catalyzed by two systems: cytochrome P450 and flavin monooxygenase. ... Amphetamine can also undergo aromatic hydroxylation to p-hydroxyamphetamine. ... Subsequent oxidation at the benzylic position by DA β-hydroxylase affords p-hydroxynorephedrine. Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

- ^ Taylor KB (January 1974). "Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Stereochemical course of the reaction" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 249 (2): 454–458. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)43051-2. PMID 4809526. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

Dopamine-β-hydroxylase catalyzed the removal of the pro-R hydrogen atom and the production of 1-norephedrine, (2S,1R)-2-amino-1-hydroxyl-1-phenylpropane, from d-amphetamine.

- ^ Cashman JR, Xiong YN, Xu L, Janowsky A (March 1999). "N-oxygenation of amphetamine and methamphetamine by the human flavin-containing monooxygenase (form 3): role in bioactivation and detoxication". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 288 (3): 1251–1260. PMID 10027866.

- ^ a b c Sjoerdsma A, von Studnitz W (April 1963). "Dopamine-beta-oxidase activity in man, using hydroxyamphetamine as substrate". British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 20 (2): 278–284. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1963.tb01467.x. PMC 1703637. PMID 13977820.

Hydroxyamphetamine was administered orally to five human subjects ... Since conversion of hydroxyamphetamine to hydroxynorephedrine occurs in vitro by the action of dopamine-β-oxidase, a simple method is suggested for measuring the activity of this enzyme and the effect of its inhibitors in man. ... The lack of effect of administration of neomycin to one patient indicates that the hydroxylation occurs in body tissues. ... a major portion of the β-hydroxylation of hydroxyamphetamine occurs in non-adrenal tissue. Unfortunately, at the present time one cannot be completely certain that the hydroxylation of hydroxyamphetamine in vivo is accomplished by the same enzyme which converts dopamine to noradrenaline.

- ^ Badenhorst CP, van der Sluis R, Erasmus E, van Dijk AA (September 2013). "Glycine conjugation: importance in metabolism, the role of glycine N-acyltransferase, and factors that influence interindividual variation". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 9 (9): 1139–1153. doi:10.1517/17425255.2013.796929. PMID 23650932. S2CID 23738007.

Figure 1. Glycine conjugation of benzoic acid. The glycine conjugation pathway consists of two steps. First benzoate is ligated to CoASH to form the high-energy benzoyl-CoA thioester. This reaction is catalyzed by the HXM-A and HXM-B medium-chain acid:CoA ligases and requires energy in the form of ATP. ... The benzoyl-CoA is then conjugated to glycine by GLYAT to form hippuric acid, releasing CoASH. In addition to the factors listed in the boxes, the levels of ATP, CoASH, and glycine may influence the overall rate of the glycine conjugation pathway.

- ^ Horwitz D, Alexander RW, Lovenberg W, Keiser HR (May 1973). "Human serum dopamine-β-hydroxylase. Relationship to hypertension and sympathetic activity". Circulation Research. 32 (5): 594–599. doi:10.1161/01.RES.32.5.594. PMID 4713201. S2CID 28641000.

The biologic significance of the different levels of serum DβH activity was studied in two ways. First, in vivo ability to β-hydroxylate the synthetic substrate hydroxyamphetamine was compared in two subjects with low serum DβH activity and two subjects with average activity. ... In one study, hydroxyamphetamine (Paredrine), a synthetic substrate for DβH, was administered to subjects with either low or average levels of serum DβH activity. The percent of the drug hydroxylated to hydroxynorephedrine was comparable in all subjects (6.5-9.62) (Table 3).

- ^ Freeman JJ, Sulser F (December 1974). "Formation of p-hydroxynorephedrine in brain following intraventricular administration of p-hydroxyamphetamine". Neuropharmacology. 13 (12): 1187–1190. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(74)90069-0. PMID 4457764.

In species where aromatic hydroxylation of amphetamine is the major metabolic pathway, p-hydroxyamphetamine (POH) and p-hydroxynorephedrine (PHN) may contribute to the pharmacological profile of the parent drug. ... The location of the p-hydroxylation and β-hydroxylation reactions is important in species where aromatic hydroxylation of amphetamine is the predominant pathway of metabolism. Following systemic administration of amphetamine to rats, POH has been found in urine and in plasma.

The observed lack of a significant accumulation of PHN in brain following the intraventricular administration of (+)-amphetamine and the formation of appreciable amounts of PHN from (+)-POH in brain tissue in vivo supports the view that the aromatic hydroxylation of amphetamine following its systemic administration occurs predominantly in the periphery, and that POH is then transported through the blood-brain barrier, taken up by noradrenergic neurones in brain where (+)-POH is converted in the storage vesicles by dopamine β-hydroxylase to PHN. - ^ Matsuda LA, Hanson GR, Gibb JW (December 1989). "Neurochemical effects of amphetamine metabolites on central dopaminergic and serotonergic systems". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 251 (3): 901–908. PMID 2600821.

The metabolism of p-OHA to p-OHNor is well documented and dopamine-β hydroxylase present in noradrenergic neurons could easily convert p-OHA to p-OHNor after intraventricular administration.

- ^ Help For Dexedrine Addicts | Dexedrine Rehab Centers For Addicts

- ^ "Dexedrine". Medic8. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Dextroamphetamine: Canadian Drug Monograph

- ^ Information on Dexedrine: A Quick Review | Weitz & Luxenberg

- ^ Prescription Forgery | Handwriting Services International

- ^ Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia (2nd edition), Marshall Sittig, Volume 1, Noyes Publications ISBN 978-0-8155-1144-1

- ^ "Dexedrine FAQs".

- ^ http://www.nbcnews.com/id/3071789/ns/us_news-only/t/go-pills-war-drugs/

- ^ a b Air Force scientists battle aviator fatigue

- ^ Emonson, DL; Vanderbeek, RD (1995). "The use of amphetamines in U.S. Air Force tactical operations during Desert Shield and Storm". Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 66 (3): 260–3. PMID 7661838.

- ^ ‘Go pills’: A war on drugs?, msnbc, 9 January 2003

- ^ a b c d e "National Drug Code Amphetamine Search Results". National Drug Code Directory. United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 16 December 2013 suggested (help) - ^ a b "Amphetamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ "Lisdexamfetamine". Drugbank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ FSC Laboratories: ProCentra (dextroamphetamine sulfate | 5 mg/5 mL Oral Solution)

- ^ Australian Prescriber | Stimulant treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- ^ http://www0.health.nsw.gov.au/PublicHealth/Pharmaceutical/adhd/faqs.asp

- ^ "Red/Amber News Iss. 22", p2. Interface Pharmacist Network Specialist Medicines (IPNSM). www.ipnsm.hscni.net. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ FDA Approval of Vyvanse Pharmacological Reviews Pages 18 and 19

- ^ Mohammad Mohammadi; Shahin Akhondzadeh (17 September 2011). "Advances and considerations in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder pharmacotherapy". Acta medica Iranica. 49 (8): 491. PMID 22009816. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

Notes

- ^ Free-base form amphetamine is a volatile oil, hence the efficacy of the inhalers.

Reference notes

External links

- Dexedrine Spansule - Official U.S. Website

- Dextroamphetamine consumer information from Drugs.com

- Poison Information Monograph (PIM 178: Dexamphetamine Sulphate)

Cite error: There are <ref group=sources> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=sources}} template (see the help page).

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).