Victoria and Albert Museum

Logo introduced in 1989 | |

The museum's main entrance | |

Former name | Museum of Manufactures, South Kensington Museum |

|---|---|

| Established | 1852 |

| Location | Cromwell Road, Kensington and Chelsea, London, SW7 |

| Coordinates | 51°29′47″N 00°10′19″W / 51.49639°N 0.17194°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Collection size | 2,800,000 objects in 145 galleries |

| Visitors | 3,110,000 (2023)[1] |

| Director | Tristram Hunt[2] |

| Owner | Non-departmental public body of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | https://www.vam.ac.uk |

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects.[3] It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

The V&A is in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, in an area known as "Albertopolis" because of its association with Prince Albert, the Albert Memorial, and the major cultural institutions with which he was associated. These include the Natural History Museum, the Science Museum, the Royal Albert Hall and Imperial College London. The museum is a non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. As with other national British museums, entrance is free.

The V&A covers 12.5 acres (5.1 ha)[4] and 145 galleries. Its collection spans 5,000 years of art, from ancient history to the present day, from the cultures of Europe, North America, Asia and North Africa. However, the art of antiquity in most areas is not collected. The holdings of ceramics, glass, textiles, costumes, silver, ironwork, jewellery, furniture, medieval objects, sculpture, prints and printmaking, drawings and photographs are among the largest and most comprehensive in the world.[5]

The museum owns the world's largest collection of post-classical sculpture, with the holdings of Italian Renaissance sculpture being the largest outside Italy. The departments of Asia include art from South Asia, China, Japan, Korea and the Islamic world. The East Asian collections are among the best in Europe, with particular strengths in ceramics and metalwork, while the Islamic collection is amongst the largest in the Western world. Overall, it is one of the largest museums in the world.

Since 2001 the museum has embarked on a major £150m renovation programme. The new European galleries for the 17th century and the 18th century were opened on 9 December 2015. These restored the original Aston Webb interiors and host the European collections 1600–1815.[6][7] The Young V&A in east London is a branch of the museum, and a new branch in London – V&A East – is being planned.[8] The first V&A museum outside London, V&A Dundee opened on 15 September 2018.[9]

History

[edit]Foundation

[edit]

The Victoria and Albert Museum has its origins in the Great Exhibition of 1851. Henry Cole was the museum's first director, he was also involved in the planning. Initially the V&A was known as the Museum of Manufactures.[10] The first opening to the general public was in May 1852 at Marlborough House. By September the collection had been transferred to Somerset House. At this stage, the collections covered both applied art and science.[11] Several of the exhibits from the opening Exhibition were purchased by the museum to form the kernel of the V&A collection.[12]

By February 1854 discussions were underway to transfer the museum to the current site[13] and the museum was renamed South Kensington Museum. In 1855 the German architect Gottfried Semper, at the request of Cole, produced a design for the museum, but it was rejected by the Board of Trade as too expensive.[14] The current site was occupied by Brompton Park House, which was extended in 1857 to include the first refreshment rooms. The V&A was the first museum in the world to provide researchers and guests a catering service.[15][5]

The official opening by Queen Victoria was on 20 June 1857.[16] In the following year, late-night openings were introduced, made possible by the use of gas lighting. In the words of museum director Cole gas lighting was introduced "to ascertain practically what hours are most convenient to the working classes".[17] To raise interest for the museum among the target audience, the museum exhibited its collections on both applied art and science. The museum aimed to provide educational resources and thus boost the productive industry.[18]

In these early years the practical use of the collection was very much emphasised as opposed to that of "High Art" at the National Gallery and scholarship at the British Museum.[19] George Wallis (1811–1891), the first Keeper of Fine Art Collection, passionately promoted the idea of wide art education through the museum collections. This led to the transfer to the museum of the School of Design that had been founded in 1837 at Somerset House; after the transfer, it was referred to as the Art School or Art Training School, later to become the Royal College of Art which finally achieved full independence in 1949. From the 1860s to the 1880s the scientific collections had been moved from the main museum site to various improvised galleries to the west of Exhibition Road.[18] In 1893 the "Science Museum" had effectively come into existence when a separate director was appointed.[20]

Queen Victoria returned to lay the foundation stone of the Aston Webb building (to the left of the main entrance) on 17 May 1899.[21] It was during this ceremony that the change of name from 'South Kensington Museum' to 'Victoria and Albert Museum' was made public. Queen Victoria's address during the ceremony, as recorded in The London Gazette, ended: "I trust that it will remain for ages a Monument of discerning Liberality and a Source of Refinement and Progress."[22]

The exhibition which the museum organised to celebrate the centennial of the 1899 renaming, A Grand Design, first toured in North America from 1997 (Baltimore Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco), returning to London in 1999.[23] To accompany and support the exhibition, the museum published a book, Grand Design, which it has made available for reading online on its website.[24]

1900–1950

[edit]The opening ceremony for the Aston Webb building by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra took place on 26 June 1909.[25] In 1914 the construction commenced of the Science Museum, signaling the final split of the science and art collections.[26]

In 1939 on the outbreak of the Second World War, most of the collection was sent to a quarry in Wiltshire, to Montacute House in Somerset, or to a tunnel near Aldwych tube station, with larger objects remaining in situ, sand-bagged and bricked in.[27] Between 1941 and 1944 some galleries were used as a school for children evacuated from Gibraltar.[28] The South Court became a canteen, first for the Royal Air Force and later for Bomb Damage Repair Squads.[28]

Before the return of the collections after the war, the Britain Can Make It exhibition was held between September and November 1946,[29] attracting nearly a million-and-a-half visitors.[30] This was organised by the Council of Industrial Design, established by the British government in 1944 "to promote by all practicable means the improvement of design in the products of British industry".[30] The success of this exhibition led to the planning of the Festival of Britain to be held in 1951. By 1948 most of the collections had been returned to the museum.

Since 1950

[edit]

In July 1973 as part of its outreach programme to young people, the V&A became the first museum in Britain to present a rock concert. The V&A presented a combined concert/lecture by the British progressive folk-rock band Gryphon, who explored the lineage of medieval music and instrumentation and related how those contributed to contemporary music 500 years later. This innovative approach to bringing young people to museums was a hallmark of the directorship of Sir Roy Strong and was subsequently emulated by some other British museums.

In the 1980s Strong renamed the museum as "The Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Museum of Art and Design". Strong's successor Elizabeth Esteve-Coll oversaw a turbulent period for the institution in which the museum's curatorial departments were re-structured, leading to public criticism from some staff. Esteve-Coll's attempts to make the V&A more accessible included a criticised marketing campaign emphasising the café over the collection.

In 2001 the museum embarked on a major £150m renovation programme, called the "FuturePlan".[31][32] The plan involves redesigning all the galleries and public facilities in the museum that have yet to be remodelled. This is to ensure that the exhibits are better displayed, more information is available, access for visitors is improved, and the museum can meet modern expectations for museum facilities.[33] A planned Spiral building was abandoned; in its place a new Exhibition Road Quarter designed by Amanda Levete's AL_A was created.[34] It features a new entrance on Exhibition Road, a porcelain-tiled courtyard (inaugurated in 2017 as the Sackler Courtyard and renamed the Exhibition Road Courtyard in 2022)[35][36] and a new 1,100-square-metre underground gallery space (the Sainsbury Gallery) accessed through the Blavatnik Hall. The Exhibition Road Quarter project provided 6,400 square metres of extra space, which is the largest expansion at the museum in over 100 years.[37] It opened on 29 June 2017.[38]

In March 2018, it was announced that the Duchess of Cambridge would become the first royal patron of the museum.[39] On 15 September 2018, the first V&A museum outside London, V&A Dundee, opened.[9] The museum, built at a cost of £80.11m, is located on Dundee's waterfront, and is focused on Scottish design, furniture, textiles, fashion, architecture, engineering and digital design.[40] Although it uses the V&A name, its operation and funding is independent of the V&A.[41]

The museum also runs the Young V&A at Bethnal Green, which reopened on 1 July 2023;[42] it used to run Apsley House, and also the Theatre Museum in Covent Garden. The Theatre Museum is now closed; the V&A Theatre Collections are now displayed within the South Kensington building.

Architecture

[edit]

Victorian parts of the building have a complex history, with piecemeal additions by different architects. Founded in May 1852, it was not until 1857 that the museum moved to its present site. This area of London, previously known as Brompton, had been renamed 'South Kensington'. The land was occupied by Brompton Park House, which was extended, most notably by the "Brompton Boilers",[43] which were starkly utilitarian iron galleries with a temporary look and were later dismantled and used to build the V&A Museum of Childhood. The first building to be erected that still forms part of the museum was the Sheepshanks Gallery in 1857 on the eastern side of the garden.[44] Its architect was civil engineer Captain Francis Fowke, Royal Engineers, who was appointed by Cole.[45] The next major expansions were designed by the same architect, the Turner and Vernon galleries built in 1858–1859[46] to house the eponymous collections (later transferred to the Tate Gallery) and now used as the picture galleries and tapestry gallery respectively. The North[47] and South Courts[48] were then built, both of which opened by June 1862. They now form the galleries for temporary exhibitions and are directly behind the Sheepshanks Gallery. On the very northern edge of the site is situated the Secretariat Wing;[49] also built in 1862, this houses the offices and boardroom, etc. and is not open to the public.

An ambitious scheme of decoration was developed for these new areas: a series of mosaic figures depicting famous European artists of the Medieval and Renaissance period.[50] These have now been removed to other areas of the museum. Also started were a series of frescoes by Lord Leighton: Industrial Arts as Applied to War 1878–1880 and Industrial Arts Applied to Peace, which was started but never finished.[51] To the east of this were additional galleries, the decoration of which was the work of another designer, Owen Jones; these were the Oriental Courts (covering India, China and Japan), completed in 1863. None of this decoration survives.[52]

Part of these galleries became the new galleries covering the 19th century, opened in December 2006. The last work by Fowke was the design for the range of buildings on the north and west sides of the garden. This includes the refreshment rooms, reinstated as the Museum Café in 2006, with the silver gallery above (at the time the ceramics gallery); the top floor has a splendid lecture theatre, although this is seldom open to the general public. The ceramic staircase in the northwest corner of this range of buildings was designed by F. W. Moody[53] and has architectural details of moulded and coloured pottery. All the work on the north range was designed and built in 1864–69. The style adopted for this part of the museum was Italian Renaissance; much use was made of terracotta, brick and mosaic. This north façade was intended as the main entrance to the museum, with its bronze doors, designed by James Gamble and Reuben Townroe, having six panels, depicting Humphry Davy (chemistry); Isaac Newton (astronomy); James Watt (mechanics); Bramante (architecture); Michelangelo (sculpture); and Titian (painting); The panels thus represent the range of the museum's collections.[54] Godfrey Sykes also designed the terracotta embellishments and the mosaic in the pediment of the North Façade commemorating the Great Exhibition, the profits from which helped to fund the museum. This is flanked by terracotta statue groups by Percival Ball.[55] This building replaced Brompton Park House, which could then be demolished to make way for the south range.

The interiors of the three refreshment rooms were assigned to different designers. The Green Dining Room (1866–68) was the work of Philip Webb and William Morris,[56] and displays Elizabethan influences. The lower part of the walls is paneled in wood with a band of paintings depicting fruit and the occasional figure, with moulded plaster foliage on the main part of the wall and a plaster frieze around the decorated ceiling and stained-glass windows by Edward Burne-Jones.[57] The Centre Refreshment Room (1865–77) was designed in a Renaissance style by James Gamble.[58] The walls and even the Ionic columns in this room are covered in decorative and moulded ceramic tile, the ceiling consists of elaborate designs on enamelled metal sheets and matching stained-glass windows, and the marble fireplace[59] was designed and sculpted by Alfred Stevens and was removed from Dorchester House prior to that building's demolition in 1929. The Grill Room (1876–81) was designed by Sir Edward Poynter;[60] the lower part of its walls consist of blue and white tiles with various figures and foliage enclosed by wood panelling, while above there are large tiled scenes with figures depicting the four seasons and the twelve months, painted by ladies from the Art School then based in the museum. The windows are also stained glass; there is an elaborate cast-iron grill still in place.

With the death of Captain Francis Fowke of the Royal Engineers, the next architect to work at the museum was Colonel (later Major General) Henry Young Darracott Scott,[61] also of the Royal Engineers. He designed to the northwest of the garden the five-storey School for Naval Architects (also known as the science schools),[62] now the Henry Cole Wing, in 1867–72. Scott's assistant J. W. Wild designed the impressive staircase[63] that rises the full height of the building. Made from Cadeby stone, the steps are 7 feet (2.1 m) in length, while the balustrades and columns are Portland stone. It is now used to jointly house the prints and architectural drawings of the V&A (prints, drawings, paintings and photographs) and Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA Drawings and Archives Collections), and the Sackler Centre for arts education, which opened in 2008.[64]

Continuing the style of the earlier buildings, various designers were responsible for the decoration. The terracotta embellishments were again the work of Godfrey Sykes, although sgraffito was used to decorate the east side of the building designed by F. W. Moody.[65] A final embellishment was the wrought iron gates made as late as 1885 designed by Starkie Gardner.[66] These lead to a passage through the building. Scott also designed the two Cast Courts (1870–73)[67] to the southeast of the garden (the site of the "Brompton Boilers"); these vast spaces have ceilings 70 feet (21 m) in height to accommodate the plaster casts of parts of famous buildings, including Trajan's Column (in two separate pieces). The final part of the museum designed by Scott was the Art Library and what is now the sculpture gallery on the south side of the garden, built in 1877–1883.[68] The exterior mosaic panels in the parapet were designed by Reuben Townroe, who also designed the plaster work in the library.[69] Sir John Taylor designed the bookshelves and cases.[69] This was the first part of the museum to have electric lighting.[70] This completed the northern half of the site, creating a quadrangle with the garden at its centre, but left the museum without a proper façade. In 1890 the government launched a competition to design new buildings for the museum, with architect Alfred Waterhouse as one of the judges;[71] this would give the museum a new imposing front entrance.

Edwardian period

[edit]The main façade, built from red brick and Portland stone, stretches 720 feet (220 m) along Cromwell Gardens and was designed by Aston Webb after winning a competition in 1891 to extend the museum. Construction took place between 1899 and 1909.[72] Stylistically it is a strange hybrid: although much of the detail belongs to the Renaissance, there are medieval influences at work. The main entrance, consisting of a series of shallow arches supported by slender columns and niches with twin doors separated by the pier, is Romanesque in form but Classical in detail. Likewise, the tower above the main entrance has an open work crown surmounted by a statue of fame,[73] a feature of late Gothic architecture and a feature common in Scotland, but the detail is Classical. The main windows to the galleries are also mullioned and transomed, again a Gothic feature; the top row of windows are interspersed with statues of many of the British artists whose work is displayed in the museum.

Prince Albert appears within the main arch above the twin entrances, and Queen Victoria above the frame around the arches and entrance, sculpted by Alfred Drury. These façades surround four levels of galleries. Other areas designed by Webb include the Entrance Hall and Rotunda, the East and West Halls, the areas occupied by the shop and Asian Galleries, and the Costume Gallery. The interior makes much use of marble in the entrance hall and flanking staircases, although the galleries as originally designed were white with restrained classical detail and mouldings, very much in contrast to the elaborate decoration of the Victorian galleries, although much of this decoration was removed in the early 20th century.[74]

-

North side of Garden, by Captain Francis Fowke, Royal Engineers, 1864–1869

-

Western Cast Court, by Henry Young Darracott Scott, 1870–1873

-

The Art Library, by Scott and other designers, 1877–1883

-

Main Entrance, by Aston Webb, 1899–1909

Post-war period

[edit]

The museum survived the Second World War with only minor bomb damage. The worst loss was the Victorian stained glass on the Ceramics Staircase, which was blown in when bombs fell nearby; pockmarks still visible on the façade of the museum were caused by fragments from the bombs.

In the immediate post-war years, there was little money available for other than essential repairs. The 1950s and early 1960s saw little in the way of building work; the first major work was the creation of new storage space for books in the Art Library in 1966 and 1967. This involved flooring over Aston Webb's main hall to form the book stacks,[75] with a new medieval gallery on the ground floor (now the shop, opened in 2006). Then the lower ground-floor galleries in the south-west part of the museum were redesigned, opening in 1978 to form the new galleries covering Continental art 1600–1800 (late Renaissance, Baroque through Rococo and neo-Classical).[76] In 1974 the museum had acquired what is now the Henry Cole wing from the Royal College of Science.[77] To adapt the building as galleries, all the Victorian interiors except for the staircase were recast during the remodelling. To link this to the rest of the museum, a new entrance building was constructed on the site of the former boiler house, the intended site of the Spiral, between 1978 and 1982.[78] This building is of concrete and very functional, the only embellishment being the iron gates by Christopher Hay and Douglas Coyne of the Royal College of Art.[78] These are set in the columned screen wall designed by Aston Webb that forms the façade.

Recent years

[edit]A few galleries were redesigned in the 1990s including the Indian, Japanese, Chinese, ironwork, the main glass galleries, and the main silverware gallery, which was further enhanced in 2002 when some of the Victorian decoration was recreated. This included two of the ten columns having their ceramic decoration replaced and the elaborate painted designs restored on the ceiling. As part of the 2006 renovation the mosaic floors in the sculpture gallery were restored—most of the Victorian floors were covered in linoleum after the Second World War. After the success of the British Galleries, opened in 2001, it was decided to embark on a major redesign of all the galleries in the museum; this is known as "FuturePlan", and was created in consultation with the exhibition designers and masterplanners Metaphor. The plan is expected to take about ten years and was started in 2002. To date several galleries have been redesigned, notably, in 2002: the main Silver Gallery, Contemporary; in 2003: Photography, the main entrance, The Painting Galleries; in 2004: the tunnel to the subway leading to South Kensington tube station, new signage throughout the museum, architecture, V&A and RIBA reading rooms and stores, metalware, Members' Room, contemporary glass, and the Gilbert Bayes sculpture gallery; in 2005: portrait miniatures, prints and drawings, displays in Room 117, the garden, sacred silver and stained glass; in 2006: Central Hall Shop, Islamic Middle East, the new café, and sculpture galleries. Several designers and architects have been involved in this work. Eva Jiřičná designed the enhancements to the main entrance and rotunda, the new shop, the tunnel and the sculpture galleries. Gareth Hoskins was responsible for contemporary and architecture, Softroom, Islamic Middle East and the Members' Room, McInnes Usher McKnight Architects (MUMA) were responsible for the new Cafe and designed the new Medieval and Renaissance galleries which opened in 2009.[79]

Garden

[edit]

The central garden was redesigned by Kim Wilkie and opened as the John Madejski Garden on 5 July 2005. The design is a subtle blend of the traditional and modern: the layout is formal; there is an elliptical water feature lined in stone with steps around the edge which may be drained to use the area for receptions, gatherings or exhibition purposes. This is in front of the bronze doors leading to the refreshment rooms. A central path flanked by lawns leads to the sculpture gallery. The north, east and west sides have herbaceous borders along the museum walls with paths in front which continues along the south façade. In the two corners by the north façade, there is planted an American Sweetgum tree. The southern, eastern and western edges of the lawns have glass planters which contain orange and lemon trees in summer, which are replaced by bay trees in winter.

At night both the planters and the water feature may be illuminated, and the surrounding façades lit to reveal details normally in shadow. Especially noticeable are the mosaics in the loggia of the north façade. In summer a café is set up in the southwest corner. The garden is also used for temporary exhibits of sculpture; for example, a sculpture by Jeff Koons was shown in 2006. It has also played host to the museum's annual contemporary design showcase, the V&A Village Fete, since 2005.

Exhibition Road Quarter

[edit]

In 2011 the V&A announced that London-based practice AL A had won an international competition to construct a gallery beneath a new entrance courtyard on Exhibition Road.[80] Planning for the scheme was granted in 2012.[81] It replaced the proposed extension designed by Daniel Libeskind with Cecil Balmond but abandoned in 2004 after failing to receive funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund.[82]

The Exhibition Road Quarter opened in 2017, with a new entrance providing access for visitors from Exhibition Road. A new courtyard, the Sackler Courtyard, has been created behind the Aston Webb Screen, a colonnade built in 1909 to hide the museum's boilers. The colonnade was kept but the wall in the lower part was removed in the construction to allow public access to the courtyard.[83] The new 1,200-square meter courtyard is the world's first all-porcelain courtyard,[38] which is covered with 11,000 handmade porcelain tiles in fifteen different linear patterns glazed in different tone. A pavilion of Modernist design with glass walls and an angular roof covered with 4,300 tiles is located at the corner and contains a cafe.[37] Skylights on the courtyard provide natural light for the stairwell and the exhibition space located below the courtyard created by digging 15m into the ground. The Sainsbury Gallery's column-less space at 1,100 square metres is one of the largest in the country, providing space for temporary exhibitions. The gallery can be assessed through the existing Western Range building where a new entrance to the Blavatnik Hall and the museum has been created, and visitors can descend into the gallery via stairs with lacquered tulipwood balustrades.[37][84][85]

Collections

[edit]The collecting areas of the museum are not easy to summarize, having evolved partly through attempts to avoid too much overlap with other national museums in London. Generally, the classical world of the West and the Ancient Near East is left to the British Museum, and Western paintings to the National Gallery, though there are all sorts of exceptions—for example, painted portrait miniatures, where the V&A has the main national collection.

The Victoria & Albert Museum is split into four curatorial departments: Decorative Art and Sculpture; Performance, Furniture, Textiles and Fashion; Art, Architecture, Photography and Design; and Asia.[86] The museum curators care for the objects in the collection and provide access to objects that are not currently on display to the public and scholars.

The collection departments are further divided into sixteen display areas, whose combined collection numbers over 6.5 million objects, not all objects are displayed or stored at the V&A. There is a repository at Blythe House, West Kensington, as well as annex institutions managed by the V&A,[87] also the museum lends exhibits to other institutions. The following lists each of the collections on display and the number of objects within the collection.

| Collection | Number of objects |

|---|---|

| Architecture (annex of the RIBA) | 2,050,000 |

| Asia | 160,000 |

| British Galleries (cross department display) | ... |

| Ceramics | 74,000 |

| Childhood (annex of the V&A) | 20,000 |

| Design, Architecture and Digital | 800 |

| Fashion & Jewellery | 28,000 |

| Furniture | 14,000 |

| Glass | 6,000 |

| Metalwork | 31,000 |

| Paintings & Drawings | 202,500 |

| Photography | 500,000 |

| Prints & Books | 1,500,000 |

| Sculpture | 17,500 |

| Textiles | 38,000 |

| Theatre (includes V&A Theatre Collections Reading Room, an annexe of the former Theatre Museum) | 1,905,000 |

The museum has 145 galleries, but given the vast extent of the collections, only a small percentage is ever on display. Many acquisitions have been made possible only with the assistance of the National Art Collections Fund.

Architecture

[edit]In 2004, the V&A alongside Royal Institute of British Architects opened the first permanent gallery in the UK[88] covering the history of architecture with displays using models, photographs, elements from buildings and original drawings. With the opening of the new gallery, the RIBA Drawings and Archives Collection has been transferred to the museum, joining the already extensive collection held by the V&A. With over 600,000 drawings, over 750,000 papers and paraphernalia, and over 700,000 photographs from around the world, together they form the world's most comprehensive architectural resource.

Not only are all the major British architects of the last four hundred years represented, but many European (especially Italian) and American architects' drawings are held in the collection. The RIBA's holdings of over 330 drawings by Andrea Palladio are the largest in the world;[89] other Europeans well represented are Jacques Gentilhatre[90] and Antonio Visentini.[91] British architects whose drawings, and in some cases models of their buildings, in the collection, include: Inigo Jones,[92] Sir Christopher Wren, Sir John Vanbrugh, Nicholas Hawksmoor, William Kent, James Gibbs, Robert Adam,[93] Sir William Chambers,[94] James Wyatt, Henry Holland, John Nash, Sir John Soane,[95] Sir Charles Barry, Charles Robert Cockerell, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin,[96] Sir George Gilbert Scott, John Loughborough Pearson, George Edmund Street, Richard Norman Shaw, Alfred Waterhouse, Sir Edwin Lutyens, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Charles Holden, Frank Hoar, Lord Richard Rogers, Lord Norman Foster, Sir Nicholas Grimshaw, Zaha Hadid and Alick Horsnell.

As well as period rooms, the collection includes parts of buildings, for example, the two top stories of the facade of Sir Paul Pindar's house[97][98] dated c. 1600 from Bishopsgate with elaborately carved woodwork and leaded windows, a rare survivor of the Great Fire of London, there is a brick portal from a London house of the English Restoration period and a fireplace from the gallery of Northumberland house. European examples include a dormer window dated 1523–1535 from the chateau of Montal. There are several examples from Italian Renaissance buildings including, portals, fireplaces, balconies and a stone buffet that used to have a built-in fountain. The main architecture gallery has a series of pillars from various buildings and different periods, for example, a column from the Alhambra. Examples covering Asia are in those galleries concerned with those countries, as well as models and photographs in the main architecture gallery.

In June 2022, the RIBA announced it would be terminating its 20-year partnership with the V&A in 2027, "by mutual agreement", ending the permanent architecture gallery at the museum. Artefacts will be transferred back to the RIBA's existing collections, with some rehoused at the institute's headquarters at 66 Portland Place building, set to become a new House of Architecture following a £20 million refurbishment.[99]

Asia

[edit]

The V&A's collection of Art from Asia numbers more than 160,000 objects, one of the largest in existence. It has one of the world's most comprehensive and important collections of Chinese art whilst the collection of South Asian Art is the most important in the West. The museum's coverage includes pieces from South and South East Asia, Himalayan kingdoms, China, the Far East and the Islamic world.

Islamic art

[edit]The V&A holds over 19,000 objects from the Islamic world, ranging from the early Islamic period (the 7th century) to the early 20th century. The Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art, opened in 2006, houses a representative display of 400 objects with the highlight being the Ardabil Carpet, the centrepiece of the gallery. The displays in this gallery cover objects from Spain, North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and Afghanistan. A masterpiece of Islamic art is a 10th-century Rock crystal ewer. Many examples of Qur'āns with exquisite calligraphy dating from various periods are on display. A 15th-century minbar from a Cairo mosque with ivory forming complex geometrical patterns inlaid in wood is one of the larger objects on display. Extensive examples of ceramics especially Iznik pottery, glasswork including 14th-century lamps from mosques and metalwork are on display. The collection of Middle Eastern and Persian rugs and carpets is amongst the finest in the world, many were part of the Salting Bequest of 1909. Examples of tile work from various buildings including a fireplace dated 1731 from Istanbul made of intricately decorated blue and white tiles and turquoise tiles from the exterior of buildings from Samarkand are also displayed.

South Asia

[edit]

The museum's collections of South and South-East Asian art are the most comprehensive and important in the West comprising nearly 60,000 objects, including about 10,000 textiles and 6,000 paintings,[100] the range of the collection is immense. The Jawaharlal Nehru gallery of Indian art, opened in 1991, contains art from about 500 BC to the 19th century. There is an extensive collection of sculptures, mainly of a religious nature, Hindu, Buddhist and Jain. The gallery is richly endowed with the art of the Mughal Empire and the Maratha Empire, including fine portraits of the emperors and other paintings and drawings, jade wine cups and gold spoons inset with emeralds, diamonds and rubies, also from this period are parts of buildings such as a jaali and pillars.[101] India was a large producer of textiles, from dyed cotton chintz, muslin to rich embroidery work using gold and silver thread, coloured sequins and beads is displayed, as are carpets from Agra and Lahore. Examples of clothing are also displayed. In 1879–80, the collections of the defunct East India Company's India Museum were transferred to the V&A and the British Museum. Items in the collection include Tipu's Tiger, an 18th-century automaton created for Tipu Sultan, the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore. The personal wine cup of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan is also on display.

East Asia

[edit]The Far Eastern collections include more than 70,000 works of art[100] from the countries of East Asia: China, Japan and Korea. The T. T. Tsui Gallery of Chinese art opened in 1991, displaying a representative collection of the V&As approximately 16,000 objects[102] from China, dating from the 4th millennium BC to the present day. Though the majority of artworks on display date from the Ming and Qing dynasties, there are objects dating from the Tang dynasty and earlier periods, among them a metre-high bronze head of the Buddha dated to about 750 AD, and one of the oldest works, a 2000-year-old jade horse head from a burial.[103] Other sculptures include life-size tomb guardians. Classic examples of Chinese decorative arts on displayt include Chinese lacquer, silk, Chinese porcelain, jade and cloisonné enamel. Two large ancestor portraits of a husband and wife painted in watercolour on silk date from the 18th century. There is a unique Chinese lacquerware table, made in the imperial workshops during the reign of the Xuande Emperor in the Ming dynasty. Examples of clothing are also displayed. One of the largest objects is a bed from the mid-17th century. The work of contemporary Chinese designers is also displayed.[citation needed]

The Toshiba gallery of Japanese art opened in December 1986. The majority of exhibits date from 1550 to 1900, but one of the oldest pieces displayed is the 13th-century sculpture of Amida Nyorai. Examples of classic Japanese armour from the mid-19th century, steel sword blades (Katana), Inrō, lacquerware including the Mazarin Chest[104] dated c1640 is one of the finest surviving pieces from Kyoto, porcelain including Imari, Netsuke, woodblock prints including the work of Andō Hiroshige, graphic works include printed books, as well as a few paintings, scrolls and screens, textiles and dress including kimono are some of the objects on display. One of the finest objects displayed is Suzuki Chokichi's bronze incense burner (koro) dated 1875, standing at over 2.25 metres high and 1.25 metres in diameter it is also one of the largest examples made. The museum also holds some cloisonné pieces from the Japanese art production company, Ando Cloisonné.

The smaller galleries cover Korea, the Himalayan kingdoms and South East Asia. Korean displays include green-glazed ceramics, silk embroideries from officials' robes and gleaming boxes inlaid with mother-of-pearl made between 500 AD and 2000. Himalayan works include important early Nepalese bronze sculptures, repoussé work and embroidery. Tibetan art from the 14th to the 19th century is represented by 14th- and 15th-century religious images in wood and bronze, scroll paintings and ritual objects. Art from Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia and Sri Lanka in gold, silver, bronze, stone, terracotta and ivory represents these rich and complex cultures, the displays span the 6th to 19th centuries. Refined Hindu and Buddhist sculptures reflect the influence of India; items on the show include betel-nut cutters, ivory combs and bronze palanquin hooks.

-

Bodhisattva Maitreya, Gandhara, Pakistan, Kusana Dynasty, 2nd-4th century AD

-

Image depicting Lord Parshvanatha, India, 7th Century

-

Image depicting Lord Rishabhanatha dated 9th century, India

-

10th-century, Rock crystal ewer

-

Jain Goddess Ambika, Odisha, India, 12th century

-

Japanese Incense Burner, Signed 'Dai Nippon, Koko Sei', Patinated bronze inlaid with gilt bronze and other soft metal alloys c. 1877

-

Betel container, 19th century, Filigree work in gold on a gold ground, outlined with bands of rubies and imitation emeralds, Mandalay, Burma

Books

[edit]The museum houses the National Art Library, a public library[105] containing over 750,000 books, photographs, drawings, paintings, and prints. It is one of the world's largest libraries dedicated to the study of fine and decorative arts. The library covers all areas and periods of the museum's collections with special collections covering illuminated manuscripts, rare books and artists' letters and archives.

The library consists of three large public rooms, with around a hundred individual study desks. These are the West Room, Centre Room and Reading Room. The centre room contains 'special collection material'.

One of the great treasures in the library is the Codex Forster, one of Leonardo da Vinci's note books. The Codex consists of three parchment-bound manuscripts, Forster I, Forster II, and Forster III,[106] quite small in size, dated between 1490 and 1505. Their contents include a large collection of sketches and references to the equestrian sculpture commissioned by the Duke of Milan Ludovico Sforza to commemorate his father Francesco Sforza.[107] These were bequeathed with over 18,000 books to the museum in 1876 by John Forster.[108] The Reverend Alexander Dyce[109] was another benefactor of the library, leaving over 14,000 books to the museum in 1869. Amongst the books he collected are early editions in Greek and Latin of the poets and playwrights Aeschylus, Aristotle, Homer, Livy, Ovid, Pindar, Sophocles and Virgil. More recent authors include Giovanni Boccaccio, Dante, Racine, Rabelais and Molière.

Writers whose papers are in the library are as diverse as Charles Dickens (that includes the manuscripts of most of his novels) and Beatrix Potter (with the greatest collection of her original manuscripts in the world).[110] Illuminated manuscripts in the library dating from the 12th to 16th centuries include: a leaf from the Eadwine Psalter, Canterbury; Pocket Book of Hours, Reims; Missal from the Royal Abbey of Saint Denis, Paris; the Simon Marmion Book of Hours, Bruges; 1524 Charter illuminated by Lucas Horenbout, London; the Armagnac manuscript of the trial and rehabilitation of Joan of Arc, Rouen.[111] also the Victorian period is represented by William Morris.

The National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum collection catalogue used to be kept in different formats including printed exhibit catalogues, and card catalogues. A computer system called MODES cataloguing system was used from the 1980s to the 1990s, but those electronic files were not available to the library users. All of the archival material at the National Art Library is using Encoded Archival Description (EAD). The Victoria and Albert Museum has a computer system but most of the items in the collection, unless those were newly accessioned into the collection, probably do not show up in the computer system. There is a feature on the Victoria and Albert Museum website called "Search the Collections," but not everything is listed there.[112]

The National Art Library also includes a collection of comics and comic art. Notable parts of the collection include the Krazy Kat Arkive, comprising 4,200 comics, and the Rakoff Collection, comprising 17,000 pieces collected by the writer and editor Ian Rakoff.[113]

The Victoria and Albert Museum's Word and Image Department was under the same pressure being felt in archives around the world, to digitise their collection. A large scale digitisation project began in 2007 in that department. That project was entitled the Factory Project to reference Andy Warhol and to create a factory to completely digitise the collection. The first step of the Factory Project was to take photographs using digital cameras. The Word and Image Department had a collection of old photos but they were in black and white and in variant conditions, so new photos were shot. Those new photographs will be accessible to researchers to the Victoria and Albert Museum web-site. 15,000 images were taken during the first year of the Factory Project, including drawings, watercolors, computer-generated art, photographs, posters, and woodcuts. The second step of the Factory Project is to catalogue everything. The third step of the Factory Project is to audit the collection. All of those items which were photographed and catalogued, must be audited to make sure everything listed as being in the collection was physically found during the creation of the Factory Project. The fourth goal of the Factory Project is conservation, which means performing some basic preventable procedures to those items in the department. There is a "Search the Collections" feature on the Victoria and Albert web-site. The main impetus behind the large-scale digitisation project called the Factory Project was to list more items in the collections in those computer databases.[112]

-

BLW Manuscript Book of Hours, about 1480–1490

-

BLW Qur'an

British galleries

[edit]These fifteen galleries—which opened in November 2001—contain around 4,000 objects. The displays in these galleries are based around three major themes: "Style", "Who Led Taste" and "What Was New". The period covered is 1500 to 1900, with the galleries divided into three major subdivisions:

- Tudor and Stuart Britain, 1500–1714, covering the Renaissance, Elizabethan, Jacobean, Restoration and Baroque styles

- Georgian Britain, 1714–1837, covering Palladianism, Rococo, Chinoiserie, Neoclassicism, the Regency, the influence of Chinese, Indian and Egyptian styles, and the early Gothic Revival

- Victorian Britain, 1837–1901, covering the later phases of the Gothic Revival, French influences, Classical and Renaissance revivals, Aestheticism, Japanese style, the continuing influence of China, India, and the Islamic world, the Arts and Crafts movement and the Scottish School.

Not only the work of British artists and craftspeople is on display, but also work produced by European artists that was purchased or commissioned by British patrons, as well as imports from Asia, including porcelain, cloth and wallpaper. Designers and artists whose work is on display in the galleries include Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Grinling Gibbons, Daniel Marot, Louis Laguerre, Antonio Verrio, Sir James Thornhill, William Kent, Robert Adam, Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton, Canova, Thomas Chippendale, Pugin, William Morris. Patrons who have influenced taste are also represented by works of art from their collections, these include: Horace Walpole (a major influence on the Gothic Revival), William Thomas Beckford and Thomas Hope.

The galleries showcase a number of complete and partial reconstructions of period rooms, from demolished buildings, including:

- The parlour from 2 Henrietta Street, London, dated 1727–1728, designed by James Gibbs

- The Norfolk House Music Room,[114] St James Square, London, dated 1756, designed by Matthew Brettingham and Giovanni Battista Borra

- A section of a wall from the Glass Drawing-Room of Northumberland House, dated 1773–1775, designed by Robert Adam

Some of the more notable works displayed in the galleries include:

- Pietro Torrigiani's coloured terracotta bust of Henry VII, dated 1509–1511

- Henry VIII's writing desk, dated 1525, made from walnut and oak, lined with leather and painted and gilded with the king's coat of arms

- A spinet dated 1570–1580, made for Elizabeth I

- The Great Bed of Ware, dated 1590–1600, a large, elaborately carved four-poster bed with marquetry headboard

- Gianlorenzo Bernini's bust of Thomas Baker, from the 1630s

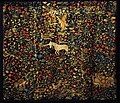

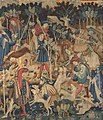

- 17th-century tapestries from the Sheldon and Mortlake Tapestry Works

- The wood relief of The Stoning of St Stephen, dated c. 1670, by Grinling Gibbons

- The Macclesfield Wine Set, dated 1719–1720, made by Anthony Nelme, the only complete set known to survive.

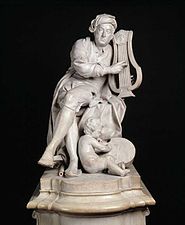

- The life-size sculpture of George Frederick Handel, dated 1738, by Louis-François Roubiliac

- Furniture by Thomas Chippendale and Robert Adam

- The sculpture of Bashaw, dated 1831–1834, by Matthew Cotes Wyatt[115]

- Aesthetic and Arts & Crafts furniture by Edward William Godwin[116] and Charles Rennie Mackintosh;[117] and carpets and interior textiles by William Morris.

The galleries also link design to wider trends in British culture. For instance, design in the Tudor period was influenced by the spread of printed books and the work of European artists and craftsmen employed in Britain. In the Stuart period, increasing trade, especially with Asia, enabled wider access to luxuries like carpets, lacquered furniture, silks and porcelain. In the Georgian age there was an increasing emphasis on entertainment and leisure. For example, the increase in tea drinking led to the production of tea paraphernalia such as china and caddies. European styles are seen on the Grand Tour also influenced taste. As the Industrial Revolution took hold, the growth of mass production produced entrepreneurs such as Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton and Eleanor Coade. In the Victorian era new technology and machinery had a significant effect on manufacturing, and for the first time since the reformation, the Anglican and Roman Catholic Churches had a major effect on art and design such as the Gothic Revival. There is a large display on the Great Exhibition which, among other things, led to the founding of the V&A. In the later 19th century, the increasing backlash against industrialisation, led by John Ruskin, contributed to the Arts and Crafts movement.

-

Henry VIII's writing box

-

Howard Grace Cup

-

Great Bed of Ware, one of the largest beds of the world

-

Norfolk House Music Room

-

Wedgwood Portland Vase

Cast courts

[edit]One of the most dramatic parts of the museum is the Cast Courts, comprising two large, skylighted rooms two storeys high housing hundreds of plaster casts of sculptures, friezes and tombs. One of these is dominated by a full-scale replica of Trajan's Column, cut in half to fit under the ceiling. The other includes reproductions of various works of Italian Renaissance sculpture and architecture, including a full-size replica of Michelangelo's David. Replicas of two earlier Davids by Donatello and Verrocchio, are also included, although for conservation reasons the Verrocchio replica is displayed in a glass case.

The two courts are divided by corridors on both storeys, and the partitions that used to line the upper corridor (the Gilbert Bayes sculpture gallery) were removed in 2004 to allow the courts to be viewed from above.

-

Room 46b; Cast Court—Plaster Cast of "Porta Magna" of San Petronio Basilica, Bologna by Jacopo della Quercia

-

Room 46a; Cast Court—Plaster Cast of the 'Pórtico da Gloria' in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

-

Cast Court—Plaster copy of Trajan's Column

-

Room 46b; Cast Court—Plaster Cast of David and The Slave, by Michelangelo

-

Cast Court post-2014 restoration

Ceramics and glass

[edit]

This is the largest and most comprehensive ceramics and glass collection in the world, with over 80,000 objects from around the world. Every populated continent is represented. Apart from the many pieces in the Primary Galleries on the ground floor, much of the top floor is devoted to galleries of ceramics of all periods covered, which include display cases with a representative selection, but also massed "visible storage" displays of the reserve collection.

Well represented in the collection is Meissen porcelain, from the first factory in Europe to discover the Chinese method of making porcelain. Among the finest examples are the Meissen Vulture from 1731 and the Möllendorff Dinner Service, designed in 1762 by Frederick II the Great. Ceramics from the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres are extensive, especially from the 18th and 19th centuries. The collection of 18th-century British porcelain is the largest and finest in the world. Examples from every factory are represented, the collections of Chelsea porcelain and Worcester porcelain being especially fine. All the major 19th-century British factories are also represented. A major boost to the collections was the Salting Bequest made in 1909, which enriched the museum's stock of Chinese and Japanese ceramics. This bequest forms part of the finest collection of East Asian pottery and porcelain in the world, including Kakiemon ware.

Many famous potters, such as Josiah Wedgwood, William De Morgan and Bernard Leach as well as Mintons & Royal Doulton are represented in the collection. There is an extensive collection of Delftware produced in both Britain and Holland, which includes a circa 1695 flower pyramid over a metre in height. Bernard Palissy has several examples of his work in the collection including dishes, jugs and candlesticks. The largest objects in the collection are a series of elaborately ornamented ceramic stoves from the 16th and 17th centuries, made in Germany and Switzerland. There is an unrivalled collection of Italian maiolica and lustreware from Spain. The collection of Iznik pottery from Turkey is the largest in the world.

The glass collection covers 4000 years of glassmaking, and has over 6000 pieces from Africa, Britain, Europe, America and Asia. The earliest glassware on display comes from Ancient Egypt and continues through the Ancient Roman, Medieval, Renaissance covering areas such as Venetian glass and Bohemian glass and more recent periods, including Art Nouveau glass by Louis Comfort Tiffany and Émile Gallé, the Art Deco style is represented by several examples by René Lalique. There are many examples of crystal chandeliers, both English,[118] displayed in the British galleries, and foreign – for example, a Venetian one attributed to Giuseppe Briati and dated to about 1750.[119] The stained glass collection is possibly the finest in the world, covering the medieval to modern periods, and covering Europe as well as Britain. Several examples of English 16th-century heraldic glass is displayed in the British Galleries. Many well-known designers of stained glass are represented in the collection including, from the 19th century: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. There is also an example of Frank Lloyd Wright's work in the collection. 20th-century designers include Harry Clarke, John Piper, Patrick Reyntiens, Veronica Whall and Brian Clarke.[120]

The main gallery was redesigned in 1994, the glass balustrade on the staircase and mezzanine are the work of Danny Lane, the gallery covering contemporary glass opened in 2004 and the sacred silver and stained-glass gallery in 2005. In this latter gallery stained glass is displayed alongside silverware starting in the 12th century and continuing to the present. Some of the most outstanding stained glass, dated 1243–1248 comes from the Sainte-Chapelle, is displayed along with other examples in the new Medieval & Renaissance galleries. The important 13th-century glass beaker known as the Luck of Edenhall is also displayed in these galleries. Examples of British stained glass are displayed in the British Galleries. One of the most spectacular works in the collection is the chandelier by Dale Chihuly in the rotunda at the museum's main entrance.

-

Flower pyramid, Delft, c. 1695

-

Jardinière (plant pot), Vincennes porcelain, France; 1750–53

-

The Luck of Edenhall, glass beaker, Syria, 13th century

-

Stained glass panel, depicting Christ's resurrection, Germany, c. 1540–42

Contemporary

[edit]These galleries are dedicated to temporary exhibits showcasing both trends from recent decades and the latest in design and fashion.

Prints and drawings

[edit]Prints and drawings from the over 750,000 works in the collection can be seen on request at the print room, the "Prints and Drawings study Room"; booking an appointment is necessary.[121] The collection of drawings includes over 10,000 British and 2,000 old master works, including works by: Dürer, Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, Bernardo Buontalenti, Rembrandt, Antonio Verrio, Paul Sandby, John Russell, Angelica Kauffman, John Flaxman,[122] Hugh Douglas Hamilton, Thomas Rowlandson, William Kilburn, Thomas Girtin, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, David Wilkie, John Martin, Samuel Palmer, Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, Lord Leighton, Sir Samuel Luke Fildes and Aubrey Beardsley. Modern British artists represented in the collection include: Paul Nash, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Eric Gill, Stanley Spencer, John Piper, Robert Priseman, Graham Sutherland, Lucian Freud and David Hockney.

The print collection has more than 500,000 objects, covering: posters, greetings cards, bookplates, as well as a comprehensive collection of old master prints from the Renaissance to the present, including works by Rembrandt, William Hogarth, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Canaletto, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Henri Matisse and Sir William Nicholson.

Fashion

[edit]The costume collection is the most comprehensive in Britain, containing over 14,000 outfits plus accessories, mainly dating from 1600 to the present. Costume sketches, design notebooks, and other works on paper are typically held by the Word and Image department. Because everyday clothing from previous eras has not generally survived, the collection is dominated by fashionable clothes made for special occasions. One of the first significant gifts of the costume came in 1913 when the V&A received the Talbot Hughes collection containing 1,442 costumes and items as a gift from Harrods following its display at the nearby department store.

Some of the oldest works in the collection are medieval vestments, especially Opus Anglicanum. One of the most important pieces in the collection is the wedding suit of James II of England, which is displayed in the British Galleries.

In 1971, Cecil Beaton curated an exhibition of 1,200 20th-century high-fashion garments and accessories, including gowns worn by leading socialites such as Patricia Lopez-Willshaw,[123] Gloria Guinness[124] and Lee Radziwill,[125] and actresses such as Audrey Hepburn[126] and Ruth Ford.[127] After the exhibition, Beaton donated most of the exhibits to the museum in the names of their former owners.

In 1999, V&A began a series of live catwalk events at the museum titled Fashion in Motion featuring pieces from historically significant fashion collections. The first show featured Alexander McQueen in June 1999. Since then, the museum has hosted recreations of various designer shows every year including Anna Sui, Tristan Webber, Elspeth Gibson, Chunghie Lee, Jean Paul Gaultier, Missoni, Gianfranco Ferré, Christian Lacroix, Kenzo and Kansai Yamamoto amongst others.[128]

In 2002, the museum acquired the Costiff collection of 178 Vivienne Westwood costumes. Other famous designers with work in the collection include Coco Chanel, Hubert de Givenchy, Christian Dior, Cristóbal Balenciaga, Yves Saint Laurent, Guy Laroche, Irene Galitzine, Mila Schön, Valentino Garavani, Norman Norell, Norman Hartnell, Zandra Rhodes, Hardy Amies, Mary Quant, Christian Lacroix, Jean Muir and Pierre Cardin.[129] The museum continues to acquire examples of modern fashion to add to the collection.

The V&A runs an ongoing textile and dress conservation programme. For example, in 2008, an important but heavily soiled, distorted and water-damaged 1954 Dior outfit called 'Zemire' was restored to displayable condition for the Golden Age of Couture exhibition.[130]

-

1770s sack-back gown

-

c. 1870 wedding dress

-

1912 Lucile evening dress

-

1954 Dior evening gown called 'Zemire'

-

[131]"Mantua gown made from an ivory silk brocaded in a pattern of stylised flowers and leaves."

The V&A Museum has a large collection of shoes around 2000 pairs from different cultures around the world. The collection shows the chronological progression of shoe height, heel shape and materials, revealing just how many styles we consider to be modern have been in and out of fashion across the centuries.[132]

Furniture

[edit]In November 2012, the museum opened its first gallery to be exclusively dedicated to furniture. Prior to this date furniture had been exhibited as part of a greater period context, rather than in isolation to showcase its design and construction merits. Among the designers showcased in the new gallery are Ron Arad, John Henry Belter, Joe Colombo, Eileen Gray, Verner Panton, Thonet, and Frank Lloyd Wright.[133][134][135]

The furniture collection, while covering Europe and America from the Middle Ages to the present, is predominantly British, dating between 1700 and 1900.[136] Many of the finest examples are displayed in the British Galleries, including pieces by Chippendale, Adam, Morris, and Mackintosh.[137] One of the oldest objects is a chair leg from Middle Egypt dated to 200-395AD.[133][138]

The Furniture and Woodwork collection also includes complete rooms, musical instruments, and clocks. Among the rooms owned by the museum are the Boudoir of Madame de Sévilly (Paris, 1781–82) by Claude Nicolas Ledoux, with painted panelling by Jean Simeon Rousseau de la Rottière;[139] and Frank Lloyd Wright's Kaufmann Office, designed and constructed between 1934 and 1937 for the owner of a Pittsburgh department store.[140]

The collection includes pieces by William Kent, Henry Flitcroft, Matthias Lock, James Stuart, William Chambers, John Gillow, James Wyatt, Thomas Hopper, Charles Heathcote Tatham, Pugin, William Burges, Charles Voysey, Charles Robert Ashbee, Baillie Scott, Edwin Lutyens, Edward Maufe, Wells Coates and Robin Day. The museum also hosts the national collection of wallpaper, which is looked after by the Prints, Drawings and Paintings department.[141][142]

The Soulages collection of Italian and French Renaissance objects was acquired between 1859 and 1865, and includes several cassone. The John Jones Collection of French 18th-century art and furnishings was left to the museum in 1882, then valued at £250,000. One of the most important pieces in this collection is a marquetry commode by the ébéniste Jean Henri Riesener dated c1780. Other signed pieces of furniture in the collection include a bureau by Jean-François Oeben, a pair of pedestals with inlaid brass work by André Charles Boulle, a commode by Bernard Vanrisamburgh and a work-table by Martin Carlin. Other 18th-century ébénistes represented in the museum collection include Adam Weisweiler, David Roentgen, Gilles Joubert and Pierre Langlois. In 1901, Sir George Donaldson donated several pieces of art Nouveau furniture to the museum, which he had acquired the previous year at the Paris Exposition Universelle. This was criticised at the time, with the result that the museum ceased to collect contemporary pieces and did not do so again until the 1960s. In 1986 the Lady Abingdon collection of French Empire furniture was bequeathed by Mrs T. R. P. Hole.

There are a set of beautiful inlaid doors, dated 1580 from Antwerp City Hall, attributed to Hans Vredeman de Vries. One of the finest pieces of continental furniture in the collection is the Rococo Augustus Rex Bureau Cabinet dated c1750 from Germany, with especially fine marquetry and ormolu mounts. One of the grandest pieces of 19th-century furniture is the highly elaborate French Cabinet dated 1861–1867 made by M. Fourdinois, made from ebony inlaid with box, lime, holly, pear, walnut and mahogany woods as well as marble with gilded carvings. Furniture designed by Ernest Gimson, Edward William Godwin, Charles Voysey, Adolf Loos and Otto Wagner are among the late 19th-century and early 20th-century examples in the collection. The work of modernists in the collection include Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Charles and Ray Eames, and Giò Ponti.

One of the oldest clocks in the collection is an astronomical clock of 1588 by Francis Nowe. One of the largest is James Markwick the younger's longcase clock of 1725, nearly 3 metres in height and japanned. Other clockmakers with work in the collection include: Thomas Tompion, Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy, John Ellicott and William Carpenter.

-

Baumhauer, Joseph—Commode, with panels of Japanese lacquer & vernis martin, French, 1760–65

-

The Evelyn Cabinet—Inlaid with panels of Florentine pietre dure; Italy, 1644–46

-

Cabinet on stand, German, c. 1580

Jewellery

[edit]

The museum's jewellery collection, containing over 6000 pieces is one of the finest and most comprehensive collections of jewellery in the world and includes works dating from Ancient Egypt to the present day, as well as jewellery designs on paper. The museum owns pieces by renowned jewellers Cartier, Jean Schlumberger, Peter Carl Fabergé, Andrew Grima, Hemmerle and Lalique.[143] Other items in the collection include diamond dress ornaments made for Catherine the Great, bracelet clasps once belonging to Marie Antoinette, and the Beauharnais emerald necklace presented by Napoleon to his adopted daughter Hortense de Beauharnais in 1806.[144] The museum also collects international modern jewellery by designers such as Gijs Bakker, Onno Boekhoudt, Peter Chang, Gerda Flockinger, Lucy Sarneel, Dorothea Prühl and Wendy Ramshaw, and African and Asian traditional jewellery. Major bequests include Reverend Chauncy Hare Townshend's collection of 154 gems bequeathed in 1869, Lady Cory's 1951 gift of major diamond jewellery from the 18th and 19th centuries, and jewellery scholar Dame Joan Evans' 1977 gift of more than 800 jewels dating from the Middle Ages to the early 19th century. A new jewellery gallery, funded by William and Judith Bollinger, opened on 24 May 2008.[145]

-

Spanish gold and emerald pendant

Metalwork

[edit]

This collection of more than 45,000 objects covers decorative ironwork, both wrought and cast, bronze, silverware, arms and armour, pewter, brassware and enamels (including many examples Limoges enamel). The main iron work gallery was redesigned in 1995.

There are over 10,000 objects made from silver or gold in the collection, the display (about 15 percent of the collection) is divided into secular[146] and sacred[147] covering both Christian (Roman Catholic, Anglican and Greek Orthodox) and Jewish liturgical vessels and other works. The main silver gallery is divided into these areas: British silver pre-1800; British silver 1800 to 1900; modernist to contemporary silver; European silver. The collection includes the earliest known piece of English silver with a dated hallmark, a silver gilt beaker dated 1496–1497.

Silversmiths whose work is represented in the collection include Paul Storr[148] (whose Castlereagh Inkstand, dated 1817–1819, is one of his finest works) and Paul de Lamerie.[149]

The main iron work gallery covers European wrought and cast iron from the medieval period to the early 20th century. The master of wrought ironwork Jean Tijou is represented by both examples of his work and designs on paper. One of the largest objects is the Hereford Screen,[150] weighing nearly 8 tonnes, 10.5 metres high and 11 metres wide, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott in 1862 for the chancel in Hereford Cathedral, from which it was removed in 1967. It was made by Skidmore & Company. Its structure of timber and cast iron is embellished with wrought iron, burnished brass and copper. Much of the copper and ironwork is painted in a wide range of colours. The arches and columns are decorated with polished quartz and panels of mosaic.

One of the rarest works in the collection is the 58 cm-high Gloucester Candlestick,[151] dated to c1110, made from gilt bronze; with highly elaborate and intricate intertwining branches containing small figures and inscriptions, it is a tour de force of bronze casting. Also of importance is the Becket Casket dated c1180 to contain relics of St Thomas Becket, made from gilt copper, with enamelled scenes of the saint's martyrdom. Another highlight is the 1351 Reichenau Crozier.[152] The Burghley Nef, a salt-cellar, French, dated 1527–1528, uses a nautilus shell to form the hull of a vessel, which rests on the tail of a parcelgilt mermaid, who rests on a hexagonal gilt plinth on six claw-and-ball feet. Both masts have main and top-sails, and battlemented fighting-tops are made from gold. These items are displayed in the new Medieval & Renaissance galleries.

-

The Becket Casket, the most elaborate, the largest and possibly the earliest Becket reliquary, Limoges enamel, c. 1180–90

-

The Burghley Nef—Silver-gilt salt cellar, France, 1527–28

-

The Gloucester Candlestick, a masterpiece of English metalwork, c. 1110

-

Tabernacle, Cologne, Germany, c. 1180

Musical instruments

[edit]Musical instruments are classified as furniture by the museum,[153] although Asian instruments are held by their relevant departments.[154]

Among the more important instruments owned by the museum are a violin by Antonio Stradivari dated 1699, an oboe that belonged to Gioachino Rossini, and a jewelled spinet dated 1571 made by Annibale Rossi.[155] The collection also includes a c. 1570 virginal said to have belonged to Elizabeth I,[156] and late 19th-century pianos designed by Edward Burne-Jones,[157] and Baillie Scott.[158]

The Musical Instruments gallery closed on 25 February 2010,[159] a decision that was highly controversial.[153] An online petition of over 5,100 names on the Parliamentary website led to Chris Smith asking in Parliament about the future of the collection.[160] The answer, from Bryan Davies, was that the museum intended to preserve and care for the collection and keep it available to the public, with objects being redistributed to the British Galleries, the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries, and the planned new galleries for Furniture and Europe 1600–1800, and that the Horniman Museum and other institutions were possible candidates for loans of material to ensure that the instruments remained publicly viewable.[160] The Horniman went on to host a joint exhibition with the V&A of musical instruments,[161] and has the loan of 35 instruments from the museum.[162]

Paintings (and miniatures)

[edit]The collection includes about 1130 British and 650 European oil paintings, 6800 British watercolours, pastels and 2000 miniatures, for which the museum holds the national collection. Also on loan to the museum, from Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II, are the Raphael Cartoons:[163] the seven surviving (there were ten) full-scale designs for tapestries in the Sistine Chapel, of the lives of Peter and Paul from the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. There is also on display a fresco by Pietro Perugino, dated 1522, from the church of Castello at Fontignano (Perugia) which is amongst the painter's last works. One of the largest objects in the collection is the Spanish retable of St George, c. 1400, 670 x 486 cm, in tempera on wood, consisting of numerous scenes and painted by Andrés Marzal De Sax in Valencia.

19th-century British artists are well represented. John Constable and J. M. W. Turner are represented by oil paintings, watercolours and drawings. One of the most unusual objects on display is Thomas Gainsborough's experimental showbox with its back-lit landscapes, which he painted on glass, which allowed them to be changed like slides. Other landscape painters with works on display include Philip James de Loutherbourg, Peter De Wint and John Ward.

In 1857 John Sheepshanks donated 233 paintings, mainly by contemporary British artists, and a similar number of drawings to the museum with the intention of forming a 'A National Gallery of British Art', a role since taken on by Tate Britain; artists represented are William Blake, James Barry, Henry Fuseli, Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, Sir David Wilkie, William Mulready, William Powell Frith, Millais and Hippolyte Delaroche. Although some of Constable's works came to the museum with the Sheepshanks bequest, the majority of the artist's works were donated by his daughter Isabel in 1888,[164] including the large number of sketches in oil, the most significant being the 1821 full size oil sketch[165] for The Hay Wain. Other artists with works in the collection include: Bernardino Fungai, Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Domenico di Pace Beccafumi, Fioravante Ferramola, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Anthony van Dyck, Ludovico Carracci, Antonio Verrio, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Domenico Tiepolo, Canaletto, Francis Hayman, Pompeo Batoni, Benjamin West, Paul Sandby, Richard Wilson, William Etty, Henry Fuseli, Sir Thomas Lawrence, James Barry, Francis Danby, Richard Parkes Bonington and Alphonse Legros.

Richard Ellison's collection of 100 British watercolours was given by his widow in 1860 and 1873 'to promote the foundation of the National Collection of Water-Color Paintings'. Over 500 British and European oil paintings, watercolours and miniatures and 3000 drawings and prints were bequeathed in 1868–1869 by the clergymen Chauncey Hare Townshend and Alexander Dyce.

Several French paintings entered the collection as part of the 260 paintings and miniatures (not all the works were French, for example Carlo Crivelli's Virgin and Child) that formed part of the Jones bequest of 1882 and as such are displayed in the galleries of continental art 1600–1800, including the portrait of François, Duc d'Alençon by François Clouet, Gaspard Dughet and works by François Boucher including his portrait of Madame de Pompadour dated 1758, Jean François de Troy, Jean-Baptiste Pater and their contemporaries.

Another major Victorian benefactor was Constantine Alexander Ionides, who left 82 oil paintings to the museum in 1901, including works by Botticelli, Tintoretto, Adriaen Brouwer, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, Eugène Delacroix, Théodore Rousseau, Edgar Degas, Jean-François Millet, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, plus watercolours and over a thousand drawings and prints

The Salting Bequest of 1909 included, among other works, watercolours by J. M. W. Turner. Other watercolourists include: William Gilpin, Thomas Rowlandson, William Blake, John Sell Cotman, Paul Sandby, William Mulready, Edward Lear, James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Paul Cézanne.

There is a copy of Raphael's The School of Athens over 4 metres by 8 metres in size, dated 1755 by Anton Raphael Mengs on display in the eastern Cast Court.

Miniaturists represented in the collection include Jean Bourdichon, Hans Holbein the Younger, Nicholas Hilliard, Isaac Oliver, Peter Oliver, Jean Petitot, Alexander Cooper, Samuel Cooper, Thomas Flatman, Rosalba Carriera, Christian Friedrich Zincke, George Engleheart, John Smart, Richard Cosway and William Charles Ross.

-

Rembrandt—The Departure of the Shunammite Woman, c. 1640

-

Tintoretto—Self-Portrait as a Young Man, c. 1548

-

Raphael—The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1515

-

Raphael—St Paul Preaching in Athens, 1515

Photography

[edit]The collection contains more than 500,000 images dating from the advent of photography, the oldest image dating from 1839. The gallery displays a series of changing exhibits and closes between exhibitions to allow full re-display to take place. Already in 1858, when the museum was called the South Kensington Museum, it had the world's first international photographic exhibition.

The collection includes the work of many photographers from Fox Talbot, Julia Margaret Cameron, Viscountess Clementina Hawarden, Gustave Le Gray, Benjamin Brecknell Turner, Frederick Hollyer, Samuel Bourne, Roger Fenton, Man Ray, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Ilse Bing, Bill Brandt, Cecil Beaton (there are more than 8000 of his negatives), Don McCullin, David Bailey, Jim Lee and Helen Chadwick to the present day.

One of the more unusual collections is that of Eadweard Muybridge's photographs of Animal Locomotion of 1887, this consists of 781 plates. These sequences of photographs taken a fraction of a second apart capture images of different animals and humans performing various actions. There are several of John Thomson's 1876-7 images of Street Life in London in the collection. The museum also holds James Lafayette's society portraits, a collection of more than 600 photographs dating from the late 19th to early 20th centuries and portraying a wide range of society figures of the period, including bishops, generals, society ladies, Indian maharajas, Ethiopian rulers and other foreign leaders, actresses, people posing in their motor cars and a sequence of photographs recording the guests at the famous fancy-dress ball held at Devonshire House in 1897 to celebrate Queen Victoria's diamond jubilee.

In 2003 and 2007 Penelope Smail and Kathleen Moffat generously donated Curtis Moffat's extensive archive to the museum. He created dynamic abstract photographs, innovative colour still-lives and glamorous society portraits during the 1920s and 1930s. He was also a pivotal figure in Modernist interior design. In Paris during the 1920s, Moffat collaborated with Man Ray, producing portraits and abstract photograms or "rayographs".

Sculpture

[edit]

The sculpture collection at the V&A is the most comprehensive holding of post-classical European sculpture in the world. There are approximately 22,000 objects[102] in the collection that cover the period from about 400 AD to 1914. This covers among other periods Byzantine and Anglo Saxon ivory sculptures, British, French and Spanish medieval statues and carvings, the Renaissance, Baroque, Neo-Classical, Victorian and Art Nouveau periods. All uses of sculpture are represented, from tomb and memorial, to portrait, allegorical, religious, mythical, statues for gardens including fountains, as well as architectural decorations. Materials used include, marble, alabaster, stone, terracotta, wood (history of wood carving), ivory, gesso, plaster, bronze, lead and ceramics.

The collection of Italian, Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque and Neoclassical sculpture (both original and in cast form) is unequalled outside of Italy. It includes Canova's The Three Graces, which the museum jointly owns with National Galleries of Scotland. Italian sculptors whose work is held by the museum include: Bartolomeo Bon, Bartolomeo Bellano, Luca della Robbia, Giovanni Pisano, Donatello, Agostino di Duccio, Andrea Riccio, Antonio Rossellino, Andrea del Verrocchio, Antonio Lombardo, Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi, Andrea della Robbia, Michelozzo di Bartolomeo, Michelangelo (represented by a freehand wax model and casts of his most famous sculptures), Jacopo Sansovino, Alessandro Algardi, Antonio Calcagni, Benvenuto Cellini (Medusa's head dated c. 1547), Agostino Busti, Bartolomeo Ammannati, Giacomo della Porta, Giambologna (Samson Slaying a Philistine c. 1562, his finest work outside Italy[according to whom?]), Bernini (Neptune and Triton c. 1622–3), Giovanni Battista Foggini, Vincenzo Foggini (Samson and the Philistines), Massimiliano Soldani Benzi, Antonio Corradini, Andrea Brustolon, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Innocenzo Spinazzi, Canova, Carlo Marochetti and Raffaelle Monti.

An unusual sculpture is the ancient Roman statue of Narcissus restored by Valerio Cioli c. 1564 with plaster. There are several small scale bronzes by Donatello such as The Ascension with Christ giving the Keys to St Peter and Lamentation of Christ, Alessandro Vittoria, Tiziano Aspetti and Francesco Fanelli in the collection. The largest work from Italy is the Chancel Chapel from Santa Chiara Florence dated 1493–1500, designed by Giuliano da Sangallo it is 11.1 metres in height by 5.4 metres square, it includes a grand sculpted tabernacle by Antonio Rossellino and coloured terracotta decoration.[166]

Rodin is represented by more than 20 works in the museum collection, making it one of the largest collections of the sculptor's work outside France; these were given to the museum by the sculptor in 1914, as acknowledgement of Britain's support of France in the First World War,[167] although the statue of St John the Baptist had been purchased in 1902 by public subscription. Other French sculptors with work in the collection are Hubert Le Sueur, François Girardon, Michel Clodion, Jean-Antoine Houdon, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux and Jules Dalou.