Sainte-Geneviève Library

| Sainte-Geneviève Library | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

| Location | 10, Place du Panthéon, 5th arrondissement of Paris |

| Type | Academic library of the universities of Paris, administered by Sorbonne Nouvelle University |

| Established | 1838 |

| Collection | |

| Items collected | two million documents, including 18,300 periodical titles |

| Other information | |

| Website | www |

Sainte-Geneviève Library (French: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, pronounced [biblijɔtɛk sɛ̃t ʒənvjɛv]) is a university library of the universities of Paris, administered by the Sorbonne-Nouvelle University (a public liberal arts and humanities university) located at 10, place du Panthéon, across the square from the Panthéon, in the 5th arrondissement of Paris.

It is based on the collection of the Abbey of St Genevieve, which was founded in the 6th century by Clovis I, the King of the Franks. The collection of the library was saved from destruction during the French Revolution. A new reading room for the library, with an innovative iron frame supporting the roof, was built between 1838 and 1851 by architect Henri Labrouste. The library contains around 2 million documents, and currently is the principal inter-university library for the different universities of Paris, and is also open to the public.[1] It is administratively affiliated with Sorbonne Nouvelle University.[2]

History

[edit]The Monastic library

[edit]The Abbey of St Genevieve is said to have been founded by King Clovis I and his queen, Clotilde. It was located near the present church of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont and the present Panthéon, which was built atop the original abbey church. The abbey was said to have been founded at the beginning of the 6th century at the suggestion of Saint Genevieve, who selected the site, across from the original Roman forum. She died in 502 and Clovis died in 511, and the basilica was completed in 520. It held the tombs of Saint Genevieve, Clovis, and his descendants.[3]

By the 9th century, the basilica had been transformed into an Abbey church, and a large monastery had grown up around it, including a scriptorium for the creation and copying of texts. The first record of the existence of the Sainte-Genevieve library dates from 831, and mentions the donation of three texts to the Abbey. The texts created or copied included works of history and literature, as well as theology, However, in the course of the 9th century, the Vikings raided Paris three times. While the settlement on the Ile-de-la-Cité was protected by the river, the abbey of Saint-Genevieve was sacked, and the books lost or carried away.[4]

The library was gradually reassembled. During the reign of Louis VI of France (1108–1137) the Abbey had a particularly important role in European scholarship. The doctrines originally taught by Saint Augustine, and promoted by Suger (1081–1151), the influential religious advisor to the King, required the reading aloud of scriptures, and specified that each monastery have a workshop to produce books and place to keep them.[5] From 1108 to 1113, the scholar Peter Abelard taught at the Abbey school, challenging many aspects of traditional theology and philosophy.

Around about 1108, the theology school of the Abbey of Saint Genevieve, was joined with the School of Notre Dame Cathedral and the school of the Royal Palace to form the future University of Paris.[5]

By the early 13th century the university library was already famous throughout Europe. The early holdings of the library from this time are listed in a 13th-century inventory (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 16203, fol. 71v). The 226 titles and authors included in the 13th century inventory include bibles, commentaries and ecclesiastical history; but also books on philosophy, law, science and literature. It was open not only to students, but also to French and foreign scholars. The manuscripts were of considerable value: each manuscript was marked with a warning notice that any person who stole or damaged a manuscript would be punished by anathema, or excommunication from the church.[6]

-

First page of The Book of Genesis, Bible of Manerius (c. 1185), (BSG Ms.8 f7)

-

Illuminated manuscript of the Coronation of King Louis IV of France (1275–1280) (Grandes Chroniques de France Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève,Ms. 782)

-

The birth of King Philip-Augustus (1275–1280) (Grandes Chroniques de France, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, folio 280)

-

Illumination in a manuscript of Livy, Ab urbe conduit, showing the foundation of Rome. (c. 1370) The manuscript belonged to king Charles V of France. Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 777, fol. 7r.

-

New Testament from the Abbey Sainte-Geneviève depicting the entry of Christ into Jerusalem Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (circa 1525–1530) (Ms. 106 f1r (Entrée à Jérusalem)

15th Century to the 18th century

[edit]Shortly after Gutenberg produced his first printed books in the mid-15th century, the library began collecting printed books. The University of Paris invited several of his collaborators to Paris to begin a new publishing house. The library possesses a text of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili published in 1499, with engravings after the drawings of Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini. At the same time, the Abbey continued to produce manuscripts illuminated by hand. The Wars of Religion seriously disrupted the activities of the library. In the 16th and 17th century he library ceased to acquire new books and stopped producing catalogs of its holdings. Many manuscripts were dispersed and sold.[7]

The library was brought back to life beginning in 1619, during the reign of Louis XIII, by Cardinal Francois de Rochefoucauld. He saw the library as an important weapon of the Counter-Reformation against Protestantism. He donated six hundred volumes from his personal collection,.[8] The new library director, Jean Fronteau, asked writers including Pierre Corneille, and famous librarians including Gabriel Naudé, to help update and expand the collection. However, he had to leave, under suspicion of being a heretical Jansenist.[9] He was succeeded by Claude Du Mollinet, librarian from 1673 until 1687. Du Mollinet founded a famous small museum, the Cabinet of Curiosities, with Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, medals, rare minerals and stuffed animals, within the library. By 1687 the library possessed twenty thousand books, and four hundred manuscripts.[10]

During the late 18th century, the library acquired copies of the major works of the Age of the Enlightenment, including the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert. In the same spirit, the library and the Cabinet of Curiosities were opened to the public. The Library was still attached to the Abbey and the University of Paris, but it ceased to be a library of theology only; by the mid-eighteenth century a majority of the works were in other fields of knowledge. While the Abbey still paid part of the cost, the major part was paid by the City of Paris.[10]

-

The Astronomical Clock (17th century)

-

The celestial globe, from the cabinet of curiosities (17th century)

-

Ceremonial Arawak baton from Cabinet of Curiosities (17th–18th century)

-

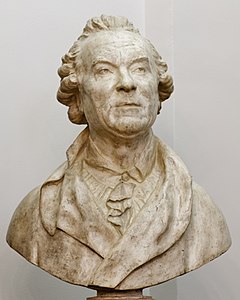

Bust of the naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon by Jean-Antoine Houdon (18th century)

The Revolution and its aftermath

[edit]Following the French Revolution, the status of the Library changed dramatically. In 1790, the Abbey was secularized, and all of its property, including the library, was confiscated, and the community of monks who ran the library was broken up. Due to the diplomatic skills of the director, Alexandre Pingré, his reputation as an astronomer and geographer, and his contacts within the new government, the collection was not dispersed, and actually grew, as the library took in the collections confiscated from other Abbeys. The library was granted equal status with the National Library, the future Mazarine Library and Arsenal Library, and could draw books from the same sources. Pingré remained as director until his death in 1796.[11]

In 1796, the name of the library was changed; it became the National Library of the Panthéon. named for the neighboring Abbey church, then under construction, which had also been confiscated and renamed. While the collection of books remained intact, the famous cabinet of Curiosities was broken up and some its collection was dispersed to the National Library and Museum of Natural History. However, the Library did manage to retain a large number of objects, including the celebrated astronomical clock, the oldest example of its kind, acquired by the library in about 1695, and a variety of terrestrial and celestial globes, as well as objects illustrating cultures around the world, which are on display in the library today. The library also displays a notable collection of eighty-six busts of French scientists, some made by the leading French sculptors of the 17th and 18th centuries, including busts by Antoine Coysevox, Jean-Antoine Houdon, and François Girardon.[12]

The early 19th century

[edit]The library continued to flourish in the early 19th century, under the French Directory and then the Empire of Napoleon. After the death of Pingré the library was directed by Pierre Claude Francois Daunou. He traveled to Rome, following Napoleon's army, and arranged for the transfer to Paris of books confiscated from the papal collections. The library also received collections of books confiscated from nobles who had fled abroad during the Revolution. At the time of the fall of Napoleon, the library had a collection of one hundred ten thousand books and manuscripts.[13]

The fall of Napoleon and the restoration of the monarchy brought new problems for the library. The collection of the library had more than doubled in size, and needed more space. However, the library shared the 18th-century building of the old Abbey Sainte-Genevieve with a prestigious school, originally known as the central school of the Panthéon, then as the Lycée Napoleon, and then and today as the Lycée Henri IV. The two institutions battled for space between 1812 and 1842. Though the library was supported by famous writers, including Victor Hugo and Jules Michelet, the son of King Louis-Philippe was a student at the lycée, and the lycée won. The library was finally expelled from its building. Some features of the old building, including the painted dome, can still be seen within the Lycée.[13]

The Labrouste building

[edit]After the expulsion of the library from its old site, the government decided to build a new building for the collection. It was the first library in Paris to be constructed specifically as a library. The site chosen was close to the old library. It had originally been occupied by the medieval Collége de Montaigu, where Erasmus and Ignatius of Loyola, John Calvin and François Rabelais had been students. After the Revolution that building had been transformed into a hospital and then a military prison, and was largely in ruins. It was to be demolished to make way for the new library.[14]

The architect chosen for the project was Henri Labrouste. Born in 1801, he had studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts where he won the Prix de Rome in 1824, and spent six years studying Italian classical and Renaissance architecture. He had received few architectural commissions, but in 1838 he received the title of Inspector of Historic Monuments, and in this capacity he began to plan the new building. Since the Lycée wanted the space as soon as possible, all the books had been moved in 1842 to a temporary library in the only surviving building of Montaigu College. His project was confirmed by the Chamber of Deputies in 1843, and a budget voted. The building was completed in December 1850. and opened to the public on 4 February 1851.[15]

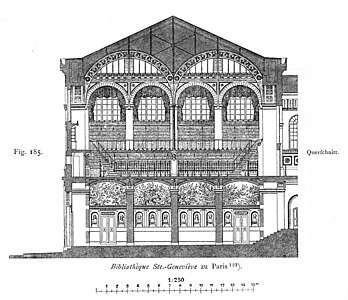

The new library showed the influence of the prevailing academic beaux-arts style and the influence of Florence and Rome, but in other ways it was strikingly original. The base and facade resembled Roman buildings, with simple arched windows and discreet bands of sculpture. The façade, exactly the length of the reading room, and the large windows, expressed the function of the building. The primary decorative element of the façade is a list of names of famous scholars.[16][17]

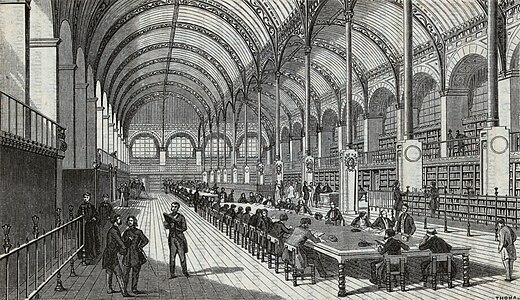

Unlike earlier buildings, the major decorative element of the building was not on the façade, but in the architecture of the reading room. The slender iron columns and the lace-like cast iron arches under the roof were not concealed; combined with the large windows they gave an immediate impression of space and lightness. It was a major step in the creation of modern architecture.[18][15]

The large (278 by 69 feet) two-storied structure filling a wide, shallow site is deceptively simple in plan: the lower floor is occupied by stacks to the left, rare-book storage and office space to the right, with a central vestibule and stairway leading to the reading room which fills the entire upper story. The vestibule was designed to symbolize the beginning of a journey in search of knowledge, the visitors arrives through a space decorated with murals of gardens and forest and passes busts of famous French scholars and scientists.[19] The monumental staircase from the ground floor to the reading room is placed so it doesn't take any space from the reading room. Labrouste also designed building so that a majority of the books (sixty thousand) were in the reading room, easily accessible, with a minority (forty thousand) in the reserves. The iron structure of this reading room—a spine of sixteen slender, cast-iron Ionic columns dividing the space into twin aisles and supporting openwork iron arches that carry barrel vaults of plaster reinforced by iron mesh—is revered by Modernists for its introduction of high technology into a monumental building.[20]

Labrouste went on to design the Salle Labrouste, the main reading room in the old Bibliothèque Nationale de France in the Rue de Richelieu, Paris, built between 1862 and 1868. Later in the century, the American architect Charles Follen McKim used the Sainte-Geneviève Library building as the model his design of the main building of the Boston Public Library.[21] It also influenced the design of university libraries in the United States, including Low Memorial Library at Columbia University in New York, the Doe Library of the University of California at Berkeley by John Galen Howard, also a former student of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and the Margaret Carnegie Library at Mills College in California, designed by Julia Morgan, also a former student of the Ecole des Beaux Arts.

-

The entry hall

-

Reading room in use

-

The reading room in 1859

-

Ground floor plan (entry hall in center and a reserves)

-

Original reading room (plan)

-

Hall and reading room (section)

-

Façade

Later years – expansion and modification

[edit]Between 1851 and 1930, the library's collection grew from one hundred thousand volumes to over a million, requiring a series of reconstructions and modifications. In 1892, a hoist was installed to lift books from the reserves to the reading room; it is now on display. A more serious change was made between 1928 and 1934. The number of seats in the reading room was doubled to seven hundred fifty. To accomplish this, the seating plan of the reading room was drastically changed; the original plan had long tables which stretched the entire length of the room, divided by a central spine of bookshelves, making the room seem even longer. In the new plan, the central bookshelves were removed and tables crossed the room, increasing the seating but reducing the linear effect.[22] As the collection continued to grow, a new annex in the modernist style was added in 1954. The later computerization of the catalog created space for an additional one hundred seats. The building was classified as a national historic monument in 1992. Today the library is classified as a national library, a university library and a public library.[23]

Notable users

[edit]Notable users of the library included the paleontologist Georges Cuvier, the botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu, the historian Jules Michelet, and Victor Hugo. It also appears as a setting in works of fiction, including in Les Illusions Perdues of Honoré de Balzac, in the novels of Simone de Beauvoir, in Ulysses by James Joyce and the writings of Guillaume Apollinaire. The Portuguese novelist Aquilino Ribeiro was a user of the library. The artist Marcel Duchamp was employed in the book reserve in 1913, at the time he was enjoying his first public exhibition in New York,[24] and in his notes for his most famous sculpture Large Glass, he recommends that those seeking to understand him "read the entire section on perspective in the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève."[25]

Directors and principal keepers

[edit]- Jean Baptiste LeChevalier (1806–1836)

- Charles Kohler ( ? – 1917)

- Charles Mortet (1917–1922)

- Paul Roux-Fouillet (1977–1987)

- Geneviève Boisard (1987–1997)

- Nathalie Jullian (1997–2006)

- Yves Peyré (2006–2015)

- François Michaud (2015 – )

In popular culture

[edit]The library's interior was used as the Film Academy Library for scenes of Martin Scorsese's Academy Award-winning 3D film Hugo, based on Brian Selznick's Caldecott Medal-winning novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret, where the title character and Isabelle go to find more information about a film which Hugo did not remember its name (A Trip to the Moon), later both finding out to their surprise that its creator is Georges Méliès, Isabelle's godfather.

References

[edit]- ^ "Accueil". www.bsg.univ-paris3.fr. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "Accueil". www.bsg.univ-paris3.fr. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ Peyré, Yves, La bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève À travers les siècles (2011), pg. 12

- ^ Peyré (2011), pg. 14

- ^ a b Peyré (2011), pg. 16

- ^ Peyré (2011), pg. 18

- ^ Peyré (2011) pp. 24–25.

- ^ Peyré (2011) pp. 28–29

- ^ Peyré (2011) pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Peyré (2011) pp. 32–33.

- ^ Peyré (2011), pg. 44

- ^ Peyré (2011), pg. 44–50

- ^ a b Peyré (2011), pg. 52–55

- ^ Peyré (2011), p. 58

- ^ a b Zanten, David Van. Designing Paris: the Architecture of Duban, Labrouste, Duc, and Vaudoyer. MIT Press, 1987.

- ^ Henri Labrouste et la bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Annie Le Saux, BBF 2002 – Paris, t. 47, n° 2

- ^ Peyré (2011), p. 62-66

- ^ "Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light". moma.org. 10 March 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ Peyré (2011), p. 70-71

- ^ Marvin Trachtenberg and Isabelle Hyman, Architecture: from Prehistory to Post-Modernism, p 478

- ^ Meyer, Adolf Bernhard (1905). Studies of the museums and kindred institutions of New York City, Albany, Buffalo, and Chicago, with notes on some European Institutions. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 594ff. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Peyré (2011), p. 78

- ^ Peyré (2011), p. 80

- ^ Peyré (2011), pp. 90–91

- ^ Duchamp, Marcel (1973). Salt seller; the writings of Marcel Duchamp. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-519749-6. OCLC 754709.

Books cited

[edit]Peyré, Yves (2011). La bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève À travers les siècles (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-013241-6.

Further reading

[edit]- "New Library". Gleason's Pictorial. 2. Boston, Mass. 1852.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in French)

- https://archive.org/details/bibliothequesaintegenevieve

- Henri Labrouste – Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (In French, Standard YouTube License)