Ha-ha

A ha-ha (French: hâ-hâ or saut de loup), also known as a sunk fence, blind fence, ditch and fence, deer wall, or foss, is a recessed landscape design element that creates a vertical barrier (particularly on one side) while preserving an uninterrupted view of the landscape beyond from the other side. The name comes from viewers' surprise when seeing the construction.

The design can include a turfed incline that slopes downward to a sharply vertical face (typically a masonry retaining wall). Ha-has are used in landscape design to prevent access to a garden by, for example, grazing livestock, without obstructing views. In security design, the element is used to deter vehicular access to a site while minimising visual obstruction.

Etymology

[edit]

The name ha-ha is of French origin, and was first used in print in Dezallier d'Argenville's 1709 book The Theory and Practice of Gardening, in which he explains that the name derives from the exclamation of surprise that viewers would make on recognising the optical illusion.[1][2][3]

Grills of iron are very necessary ornaments in the lines of walks, to extend the view, and to show the country to advantage. At present we frequently make thoroughviews, called Ah, Ah, which are openings in the walls, without grills, to the very level of the walks, with a large and deep ditch at the foot of them, lined on both sides to sustain the earth, and prevent the getting over; which surprises the eye upon coming near it, and makes one laugh, Ha! Ha! from where it takes its name. This sort of opening is, on some occasions, to be preferred, for that it does not at all interrupt the prospect, as the bars of a grill do.

— D. d'Argenville (1709)[4]

The name ha-ha is attested in toponyms in New France from 1686 (as seen today in Saint-Louis-du-Ha! Ha!), and is a feature of the gardens of the Château de Meudon, circa 1700.

In a letter to Daniel Dering in 1724, John Perceval (grandfather to the prime minister Spencer Perceval), observed of Stowe:

What adds to the beauty of this garden is, that it is not bounded by walls, but by a ha-hah, which leaves you the sight of the beautiful woody country, and makes you ignorant how far the high planted walks extend.[5]

In the 18th century, they were often called a sunken or sunk fence, at least in formal writing, as by Horace Walpole, George Mason, and Humphry Repton.[6] Walpole also referred to them as Kent-fences, named after William Kent.[7]

Walpole surmised that the name is derived from the response of ordinary folk on encountering them and that they were "then deemed so astonishing, that the common people called them Ha! Has! to express their surprise at finding a sudden and unperceived check to their walk."

Thomas Jefferson, describing the garden at Stowe after his visit in April 1786, also uses the term with exclamation marks: "The inclosure is entirely by ha! ha!"[8]

George Washington called it both a "ha haw" and a "deer wall".[9]

Origins

[edit]

Before mechanical lawn mowers, a common way to keep large areas of grassland trimmed was to allow livestock, usually sheep, to graze the grass. A ha-ha prevented grazing animals on large estates from gaining access to the lawn and gardens adjoining the house, giving a continuous vista to create the illusion that the garden and landscape were one and undivided.[10][11][12]

The basic design of sunken ditches is of ancient origin, being a feature of deer parks first found in Anglo-Saxon England. The deer-leap or saltatorium consisted of a ditch with one steep side surmounted by a pale (picket-style fence made of wooden stakes) or hedge, which allowed deer to enter the park but not to leave. Since the time of the Norman conquest of England the right to construct a deer-leap was granted by the king, with reservations made as to the depth of the foss or ditch and the height of the pale or hedge.[13] On Dartmoor, the deer-leap was known as a "leapyeat".[14]

In Britain, the ha-ha is a feature of the landscape gardens laid out by Charles Bridgeman and William Kent and was an essential component of the "swept" views of Capability Brown. Horace Walpole credits Bridgeman with the invention of the ha-ha but was unaware of the earlier French origins.

The contiguous ground of the park without the sunk fence was to be harmonized with the lawn within; and the garden in its turn was to be set free from its prim regularity, that it might assort with the wilder country without.

— Horace Walpole, Essay upon Modern Gardening, 1780[15]

During his excavations at Iona in the period 1964–1984, Richard Reece discovered an 18th-century ha-ha designed to protect the abbey from cattle.[16] Ice houses were sometimes built into ha-ha walls because they provide a subtle entrance that makes the ice house a less intrusive structure, and the ground provides additional insulation.[17]

Examples

[edit]

Most typically, ha-has are still found in the grounds of grand country houses and estates. They keep cattle and sheep out of the formal gardens, without the need for obtrusive fencing. They vary in depth from about 0.6 m (2 ft) (Horton House) to 2.7 m (9 ft) (Petworth House).

Beningbrough Hall in Yorkshire is separated from its extensive grounds by a ha-ha to prevent sheep and cattle from entering the Hall's gardens or the Hall itself.[18]

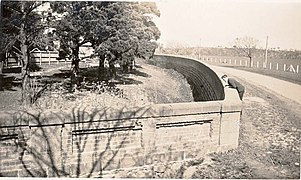

An unusually long example is the ha-ha that separates the Royal Artillery Barracks Field from Woolwich Common in southeast London. This deep ha-ha was installed around 1774 to prevent sheep and cattle, grazing at a stopover on Woolwich Common on their journey to the London meat markets, from wandering onto the Royal Artillery gunnery range. A rare feature of this east-west ha-ha is that the normally hidden brick wall emerges above ground for its final 75 yards (70 metres) or so as the land falls away to the west, revealing a fine batter to the brickwork face of the wall, thus exposed. This final west section of the ha-ha forms the boundary of the Gatehouse[19] by James Wyatt RA. The Royal Artillery ha-ha is maintained in a good state of preservation by the Ministry of Defence. It is a Listed Building, and is accompanied by Ha-Ha Road that runs alongside its full length. There is a shorter ha-ha in the grounds of the nearby Jacobean Charlton House. The Royal Crescent row of 30 terraced houses in Bath, Somerset, which were built between 1767 and 1774 in the Georgian architecture style, also feature a large ha-ha that provides an uninterrupted view of Royal Victoria Park.[20]

In Australia, ha-has were also used at Victorian-era lunatic asylums such as Yarra Bend Asylum, Beechworth Asylum, and Kew Lunatic Asylum in Victoria, and the Parkside Lunatic Asylum in South Australia. From the inside, the walls presented a tall face to patients, preventing them from escaping, while from outside they looked low so as not to suggest imprisonment.[21] For the patients themselves, standing before the trench, it also enabled them to see the wider landscape.[22] Kew Asylum has been redeveloped as apartments; however some of the ha-has remain, albeit partially filled in.

- Ha-ha variations used at Australian mental asylums

-

Remains of the original ha-ha wall at Beechworth Asylum from the "outside" of the original asylum boundary

-

From the inside, the ha-ha was a barrier to passage

-

End view at the beginning of the remains of the ha-ha at Beechworth Asylum, showing the sloping trench

-

An example of the ha-ha variation used at Yarra Bend Asylum in Victoria, Australia, circa 1900

Ha-has were also used in North America. Only two historic installations remain in Canada, one of which is on the grounds of Nova Scotia's Uniacke House (1813), a rural estate built by Richard John Uniacke, an Irish-born Attorney-General of Nova Scotia.[23]

Mount Vernon, the plantation of George Washington, incorporates ha-haws on its grounds as part of the landscaping for the mansion built by George Washington’s father, Augustine Washington.[24] A later American president, Thomas Jefferson, "built a ha-ha at the southern end of the South Lawn [of the White House], which was an eight-foot wall with a sunken ditch meant to keep the livestock from grazing in his garden."[25]

A 21st-century use of a ha-ha is at the Washington Monument to minimise the visual impact of security measures. After 9/11 and another unrelated terror threat at the monument, authorities had put up jersey barriers to prevent large motor vehicles from approaching the monument. The temporary barriers were later replaced with a new ha-ha, a low 0.76 m (30-inch) granite stone wall that incorporated lighting and doubled as a seating bench. It received the 2005 Park/Landscape Award of Merit.[26][27][28]

In fiction

[edit]- In Jane Austen's Mansfield Park (1814), a ha-ha prevents the more sensible characters from getting around a locked gate and into the woodland beyond.[29]

- In Anthony Trollope's Barchester Towers (1857), a ha-ha marks the social divisions in Miss Thorne's fête champêtre: "Two marquees had been erected for these two banquets: that for the quality on the esoteric or garden side of a certain deep ha-ha; and that for the non-quality on the exoteric or paddock side of the same."[30]

- In J.J. Connington's 's 1934 detective novel The Ha-Ha Case a murder is committed in a ha-ha during a shooting party.[31]

- In Terry Pratchett's Men at Arms, the grounds of the Patrician's Palace, created by the infamous Bloody Stupid Johnson, includes a ho-ho, which is described as like a ha-ha only much deeper. In the later book Snuff the grounds of the Ramkins' county estate have a both a ho-ho and a ha-ha, as well as a he-he and a ho-hum, implied to be much shallower.[32]

Legal

[edit]Personal injury

[edit]Due to the hidden nature of ha-has, they can pose potential injury to the public (especially considering their initial designs were to be invisible).

- In 2008, during a nighttime guided walk to watch bats at Hopetoun House (Scotland), a participant of the walk attempting to make his way back to the carpark fell off a ha-ha wall, and suffered a severe fracture to the ankle. A successful personal injury claim of £35,000 was settled upon, as the judge presiding the case deemed the ha-ha to be a dangerous man-made feature, and thus it was up to the groundskeepers to highlight the invisible danger that it presented.[33] The presiding QC judge, Alastair Campbell, deemed a ha-ha wall to be outside the scope of the law regarding obvious dangers, such as cliffs or canals, where an occupier is not required to take precautions against a person being injured. This was due to its being an unusual man-made feature that the public would be very much unaware of, especially across a wide lawn.[34]

- In 2014, a wedding guest at a British manor house fell off a ha-ha while making her way across the manor garden, displacing her right tibia and fibula bones. She brought a successful personal injury claim that was investigated by the environmental health department, which agreed that the area should have been lit in some way to avoid this kind of accident.[35] The defendants in the litigation case were quick to admit liability for the incident, and settled for about £10,000. This was followed by radical changes to the signposting and lighting around the ha-ha to alert visitors of its presence.[35]

Preventive repairs

[edit]- Emergency repairs to the ha-ha wall at Sunbury Park in Spelthorne (England) took place in 2009, after the council realised that they would be liable for any injury or death caused by the ha-ha wall. Surrounding vegetation was removed two years before the works opened up the ha-ha to the public. However environmental services were made aware that the ha-ha was in a state of disrepair, and without appropriate warning signs. The total cost of repairs was thought to be around £65,000; environmental services contributed £9,000, and the rest of the funds was taken from capital funds.[36]

- In 2016, the ha-ha wall in Dalzell estate (Scotland) was repaired after it became unsafe due to a collapse of the stonework. The council's Environmental Services Committee were concerned about potential liability and personal injury claims and enlisted the help of volunteers and staff from a local charity to repair the ha-ha wall within the estate. The repair project received funding from the environmental key fund and the heritage lottery fund via the Clyde and Avon Valley Landscape Partnership.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "What is a ha-ha?". National Trust. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ d' Harmonville, A.-L. (1842). Dictionnaire des dates, des faits, des lieux, et des hommes historiques: Ou, les tables de l'histoire, répertoire alphabétique de chronologie universelle ... [Dictionary of Historical Dates, Facts, Places, and Men: Or, the tables of history, alphabetical directory of universal chronology] (in French). A. Levavasseur et Cie. p. 65.

- ^ "What's so funny about a ha-ha wall?". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ d'Argenville, D. (1709). La théorie et la pratique du jardinage [The Theory and Practice of Gardening] (in French). Translated by James, John (published 1712).

- ^ Clarke, G.B., ed. (1990). Descriptions of Lord Cobham's Gardens at Stowe (1700–1750). Buckinghamshire Record Society. ISBN 0901198250.

- ^ Robinson, Philip (2007). The Faber Book of Gardens. Faber & Faber. pp. 119, 124, 143. ISBN 978-0571-22421-0.

- ^ Batey, Mavis (1991). "Horace Walpole as modern garden historian: The president's lecture on the occasion of the society's 25th anniversary, AGM, held at Strawberry Hill, Twickenham, 19 July 1990". Garden History. 19 (1): 1–11. doi:10.2307/1586988. JSTOR 1586988.

- ^ Oberg, Barbara B.; Looney, J. Jefferson, eds. (2008). The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (digital ed.). Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda. p. 371. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "Ha-ha/sunk fence". History of Early American Landscape Design. heald.nga.gov.

- ^ "West Dean College". heald.nga.gov. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

From the front the parkland landscape appears continuous, but in fact the formal grounds are protected from the grazing sheep and cattle by a ha-ha

- ^ "Lawn Pros and Cons". Pat Welsh. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ "Massachusetts Agriculture". Archived from the original on 16 January 2009.

Early suburbanites relied on hired help to scythe the grass or sheep to graze the lawn. The lawn mower ... made it possible for homeowners to maintain their own lawn. ... The ha-ha provided an invisible barrier ... which kept livestock from wandering ... into gardens.

- ^ Shirley, Evelyn Philip (1867). "1 Deer and deer parks". Some account of English deer parks: with notes on the management of deer. London: John Murray. p. 14. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

deer leap.

- ^ Anon. "Okehampton Deer Park". Legendary Dartmoor. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Horace Walpole (1780). "Essay upon modern gardening". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ Hamlin, Ann (1987). "Iona: a view from Ireland". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 117: 17. doi:10.9750/PSAS.117.17.22. ISSN 0081-1564.

- ^ Walker, Bruce (1978). Keeping it cool. Edinburgh & Dundee: Scottish Vernacular buildings Working Group. pp. 564–565.

- ^ Historic England. "Beningbrough Hall (1001057)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ "The Gatehouse". LargeAssociates.com. Large and Associates Consulting Engineers. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Royal Crescent Lawn 'Ha Ha' and its History". Royal Crescent, Bath. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "Kew Lunatic Asylum — Historical Walk" – via Australian Science Archives Project.

- ^ Semple Kerr, James (1988). Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Australia's places of confinement, 1788–1988. National Trust of Australia. p. 158. ISBN 0-947137-80-7.

- ^ Anon (29 January 2013). "About Uniacke Estate". Nova Scotia Museum. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ "Mount Vernon – History of Early American Landscape Design". heald.nga.gov.

- ^ Holland, Jesse J. (2016). The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-4930-0846-9.

- ^ "Washington Monument". OLIN. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Monumental Security". American Society of Landscape Architects. 10 April 2006. Archived from the original on 29 September 2006.

- ^ Risk Management Series: Site and Urban Design for Security. U. S. Department Security, Federal Emergency Agency. 27 January 2013. pp. 4–17.

- ^ Clark, Robert, Wilderness and Shrubbery in Austen’s Works, Persuasions On-line, The Jane Austen Society of America, Volume 36, No. 1 — Winter 2015

- ^ Bridgham, Elizabeth A., Spaces of the Sacred and Profane: Dickens, Trollope, and the Victorian Cathedral Town, p. 140, 2012, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781135863128, google books

- ^ * Evans, Curtis. Masters of the "Humdrum" Mystery: Cecil John Charles Street, Freeman Wills Crofts, Alfred Walter Stewart and the British Detective Novel, 1920-1961. McFarland, 2014. p.227

- ^ * Briggs, Stephen and Pratchett, Terry. The Ultimate Discworld Companion. Victor-Golancz, 2021. p.281

- ^ "JOHN COWAN v. THE HOPETOUN HOUSE PRESERVATION TRUST AND OTHERS". www.scotcourts.gov.uk.

- ^ "Bat walk man wins damages after ditch fall". HeraldScotland. 18 January 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Personal injury team secures compensation for Manor House guest". www.penningtons.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Muirhead, Sandy (24 July 2007). "Sunbury Park Ha-Ha Repairs" (PDF). LOSRA (The Lower Sunbury Residents' Association). Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ Service Manager, Scott House (23 June 2016). "Volunteers restore historic feature". Retrieved 29 November 2017.

![]() Media related to Ha-has at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ha-has at Wikimedia Commons