Tropaeum Traiani

The Tropaeum Traiani or Trajan's Trophy lies 1.4 km northeast of the Roman city of Civitas Tropaensium (near the modern Adamclisi, Romania). It was built in AD 109 in then Moesia Inferior, to commemorate Roman Emperor Trajan's victory over the Dacians in 106, including the victory at the Battle of Adamclisi nearby in 102.[1]

It was part of a monumental complex comprising the trophy monument, the tumulus grave behind it and the commemorative altar, raised in 102 AD for soldiers fallen in the battles of this region. The complex forms a triangular plan, the base being marked by the monument and the funerary tumulus while the upper point is the altar.

Trophy monument

[edit]The trophy monument was built, according to the inscription, between 106 and 109 AD probably by Apollodorus of Damascus, Trajan's favoured architect and engineer. It was inspired by the Augustus mausoleum, and was dedicated to Mars Ultor. It is a cylindrical building, with steps at the base, of diameter 40 m. Around the side were 54 metopes, showing Romans fighting Decebalus's allies, of which 48 are in the local museum and 1 is in Istanbul. The reliefs were framed by friezes and separated by decorative pilasters. The upper part was festooned with 27 battlements, each one showing prisoners. The cone-shaped roof was made of stone slabs and the trophy itself was placed on top of two superposed prisms, framed by two sitting women and a standing man with his hands held behind.

The monument was perhaps a warning to the tribes outside this newly conquered province.[2]

Compared to Trajan's Column in Rome, erected to celebrate the same victories and a "product of Roman metropolitan art", the sculpted metopes have been described as in "barbarian provincial taste", carved by "sculptors of provincial training, reveal[ing] a lack of experience in figurative representation, in organic structure and a naive idiom that remains detached from the classical current".[3]

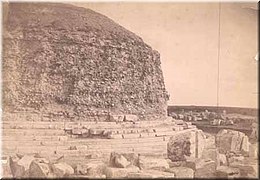

By the 20th century, the monument was reduced to a mound of stone and mortar, with a large number of the original bas-reliefs scattered around. The present edifice is a reconstruction dating from 1977. The nearby museum contains many archaeological objects, including parts of the original Roman monument.

-

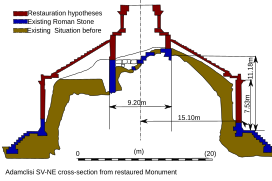

Cross-section of the reconstruction

-

Three hypothetical reconstructions

-

1896 picture

-

Furtwangler picture

The monument was dedicated with a large inscription to Mars Ultor (the avenger). The inscription has been preserved fragmentarily from two sides of the trophy hexagon, and has been reconstructed as follows:

MARTI ULTOR[I]

IM[P(erator)CAES]AR DIVI

NERVA[E] F(ILIUS) N[E]RVA

TRA]IANUS [AUG(USTUS) GERM(ANICUS)]

DAC]I[CU]S PONT(IFEX) MAX(IMUS)

TRIB(UNICIA) POTEST(ATE) XIII

IMP(ERATOR) VI CO(N)S(UL) V P(ater) P(atriae)

?VICTO EXERC]ITU D[ACORUM]

?---- ET SARMATA]RUM

----]E 31.[4]

The inscription, which calls Trajan Germanicus from his previous victories in Germany and Dacicus for his new conquest of Dacia, can be translated:

To Mars Ultor,

Caesar the emperor, son of the divine Nerva,

Nerva Trajan Augustus, Germanicus,

Dacicus, Pontifex Maximus,

Plebeian tribune for the 13th time,

[proclaimed] Emperor [by the army] for the 6th time,

Consul for the 5th time, Father of the Fatherland,

Conquered the Dacian and Sarmatian armies ...

-

The reconstructed trophy

-

the original trophy

-

Detail of the trophy: Head of Medusa

-

Detail of a falx on the trophy

-

Roman roof stone tile used for the monument

The altar

[edit]The altar was raised in 102 to honour the soldiers who died "fighting for the Republic" perhaps at the Battle of Adamclisi nearby in the winter of 101–102. The altar had a rectangular shape, 12 m long and 6 m high. In the vicinity fragments of 1.3 x 0.9 m slabs covered with inscriptions were discovered with a dedication, but the name of the emperor was not preserved the names of about 4,000 soldiers were written on it.[5]

Several hypotheses for the soldiers and general commemorated have been put forward, including the soldiers of Oppius Sabinus, defeated somewhere nearby.[6] The mention of the cohort II Batavorum and probably of the Legio XV Apollinaris, as well as the formula missici (instead of veterans) usual for the first century BC indicates that the war must be dated to the era of Domitian and probably in the year 86, the campaign led by M. Cornelius Nigrinus.[7]

The General's grave

[edit]

The tumulus grave was also built in 102 shortly after the altar and contained the grave of a Roman officer killed in the battle in Adamclisi, possibly Oppius Sabinus.

Archaeology

[edit]In 1837, four Prussian officers, hired by the Ottoman Empire to study the Dobruja strategic situation, performed the first excavations.[8]

The monument was researched between 1882–1895,[9] George Murnu in 1909, Vasile Parvan in 1911, Paul Nicorescu studied the site between 1935–1945, Gheorghe Stefan and Ioan Barnea in 1945. From 1968 the site was researched under Romanian Academy supervision.

Metopes

[edit]On the monument was a frieze comprising 54 metopes. 48 metopes are hosted in the Adamclisi museum nearby, and one metope is hosted by Istanbul Archaeology Museum, the rest having been lost (There is a reference from Giurescu that two of them fell into the Danube during the transport to Bucharest).[10]

-

Metope II

-

VI: Trajan’s equestrian statue crushing the enemy under the legs of the horse (Gramatopol)

-

IV The Suicide of Decebalus-Tiberius Claudius Maximus (according to M.P Spiedel)

-

VII: the bodies of the Dacians thrown off the cliffs (Gramatopol)

-

tabula ansata on the right side of the boss on a soldier shield, metope XXIV from Tropaeum Traiani

-

Adamclisi, imperial metope X: Trajan between two adjutants (according to M. Gramatopol)

-

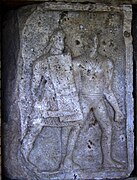

Metope XXXV: A Roman Legionary with a mail manica and spear with Dacian falxman

-

This metope was later reused as part of a fountain, then recovered and placed in the museum

-

XXIV: the bodies of the Dacians thrown off the cliffs

-

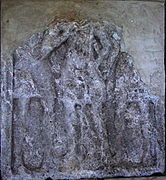

IX - Barbarian family in a four-wheel cart

-

XLVIII: Germanic POW with Roman Soldier

-

XXII: Emperor Trajan[8]

-

XLIV(Gramatopol) changed as Metope XXXIX: Marching "offduty" soldiers

-

XXXI: pursuing the Dacian archers hiding in the trees (Gramatopol)

-

Emperor Trajan with a Lieutenant[8]

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Traian Metope, Istanbul Museum

-

Germanic captive[8]

References

[edit]- ^ Tropaeum Traiani https://cimec.ro/id-01-arheologie/situri-arheologice-22/tropaeum-traiani/

- ^ F.B. Florescu. Das Siegesdenksmal von Adamclisi: Tropaeum Traiani (1965)

- ^ Henig, Martin (ed), A Handbook of Roman Art, p. 68, Phaidon, 1983, ISBN 0714822140

- ^ "Tropaeum Traiani". cimec.ro.

- ^ Tropaeum Traiani https://cimec.ro/id-01-arheologie/situri-arheologice-22/tropaeum-traiani/

- ^ R. Syme, Danubian Papers, Bucuresti, 1971, 73-83; the same dating seems certain also to K. Strobel, Anhang IV în Untersuchungen zu den Dakerkriegen Trajans, Bonn, 1984, 237 sqq

- ^ G. Alföldy, H. Halfmann, în Chiron, III, 1973, 331 sqq – M. Cornelius Nigrinus a fost în anii 85-89 guvernatorul Moesiei, iar apoi al Moesiei Inferior

- ^ a b c d Vasile Barbu, Cristian Schuster Grigore G. Tocilescu si "Cestiunea Adamclisi" Pagini din Istoria Arheologiei Romanesti ISBN 7-379-25580-0

- ^ Cimec http://www.cimec.ro/scripts/muzee/id.asp?k=246 Archived 2021-08-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "1900 Years since the Inauguration of Tropaeum Trajani from Adamclisi - 10 lei silver 2009 - Romanian Coins". romaniancoins.org.

Sources

[edit] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

|

|

- Adolf Furtwängler: Das Tropaion von Adamklissi und provinzialrömische Kunst. (München, Verlag der K. Akademie, 1903) Das Tropaion von Adamklissi und provinzialromische Kunst: Furtwängler, Adolf, 1853-1907: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming

- Florea Bobu Florescu, Das Siegesdenkmal von Adamklissi. Tropaeum Traiani. Akademieverlag, Bukarest 1965.

- Wilhelm Jänecke, Die ursprüngliche Gestalt des Tropaion von Adamklissi. Winter, Heidelberg 1919.

- Adrian V. Rădulescu, Das Siegesdenkmal von Adamklissi. Konstanza 1972 und öfter.

- Ian A. Richmond: Adamklissi, en Papers of the British School at Rome 35, 1967, pp. 29–39.

- Lino Rossi, A Synoptic Outlook of Adamklissi Metopes and Trajan’s Column Frieze. Factual and Fanciful Topics Revisited, en Athenaeum 85, 1997, pp. 471–486.

- Luca Bianchi, Il trofeo di Adamclisi nel quadro dell'arte di stato romana, in Rivista dell'Istituto Nazionale d Archeologia e Storia dell'Arte 61, 2011, pp. 9-61 Ahttp://arche-o.nolblog.hu/page/2/

- Brian Turner. 2013. "War Losses and Worldview: Re-Viewing the Roman Funerary Altar at Adamclisi." American Journal of Philology 134.2:277-304. DOI: War Losses and Worldview: Re-Viewing the Roman Funerary Altar at Adamclisi.

![XXII: Emperor Trajan[8]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/06/AdamclisiMetope25.jpg/135px-AdamclisiMetope25.jpg)

![Emperor Trajan with a Lieutenant[8]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/AdamclisiMetope42.jpg/149px-AdamclisiMetope42.jpg)