Diferencia entre revisiones de «Tratado de los tres impostores»

Bot:Reparando enlaces |

m Bot: ajustando referencias al Manual de estilo. Las referencias y notas al pie deben ir junto a los signos de puntuación. |

||

| (No se muestran 13 ediciones intermedias de 11 usuarios) | |||

| Línea 1: | Línea 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Referencias|t=20110801|literatura}} |

||

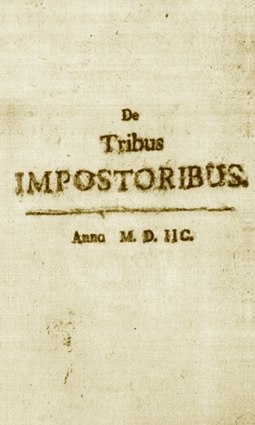

[[Archivo:De tribus impostoribus.jpg|miniaturadeimagen|255px|Primera edición del ''De tribus impostoribus'' (''Sobre los tres impostores''), Viena, Straub, 1753, pero con la fecha (falsa) de 1598.]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

El '''''Tratado de los tres impostores''''' (en [[latín]], ''De tribus impostoribus''), también conocido como '''''El espíritu de Spinoza''''', es el nombre de una obra que niega las tres [[Religión abrahámica|religiones abrahámicas]]. Los «tres impostores» del título serían [[Moisés]], [[Cristo]] y [[Mahoma]]. En él se sostiene que los tres representantes de las grandes religiones [[Religiones abrahámicas|abrahámicas]] han engañado a la humanidad imponiéndole las ideas de Dios, obligando al pueblo a creerlas sin permitirle examinarlas.<ref>{{Cita libro|edición=1.ª|título=Apuntes sobre el suicidio|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/957749337|editorial=Alpha Decay|fecha=2016|fechaacceso=2021-02-22|isbn=978-84-944896-2-4|oclc=957749337|nombre=Simon|apellidos=Critchley|página=27}}</ref> |

|||

== El mito del Tratado == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | * A mediados del |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

== |

== ¿Un mito? == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | El origen del libro se encontraría en el texto ''De imposturis religionum'', un ataque anónimo al cristianismo publicado en |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | * A mediados del {{siglo|XI||s}}, [[Tomás de Cantimpré]]<ref>Thomas de Cantimpré, ''De apibus''. Véase el artículo, firmado por P. R. sobre Simón de Tournai en ''Histoire littéraire de la France'', t. 16, Paris, 1824, pp. 390-391, consultable en [http://books.google.be/books?id=eVIZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA392&lpg=PA392&dq=trois+imposteurs+%22Simon+de+Tournai%22&source=bl&ots=qyiVFNcAlq&sig=9_Jg_FjJmoCn3n4jfNmNnxBVLsw&hl=fr&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result#PPA390,M1 Google Libros].</ref> atribuía la obra sobre los «tres impostores» al canónigo [[Simón de Tournai]] (''circa'' 1184-1200). |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

== ''De imposturis religionum'' == |

|||

| ⚫ | El origen del libro se encontraría en el texto ''De imposturis religionum'', un ataque anónimo al cristianismo publicado en 1598 (aunque datado anteriormente por G. Bartsch), y que se dio a conocer en la subasta de la biblioteca del teólogo de [[Greifswald]] [[Johann Friedrich Mayer]] en 1716. A partir de este texto el jurista [[Johannes Joachim Müller]] (1661–1733) escribió dos textos más, contra Moisés y contra Mahoma, publicando los tres textos de forma conjunta en 1753 como ''De Tribus Impostoribus''. El primer rastro del libro se encuentra en un manuscrito de [[Prosper Marchand]], una carta a su amigo Fritsch. En ella, Marchand recuerda a Fritsch cómo otro amigo común, [[Benjamin Furly]], había obtenido la obra de una biblioteca en 1711. La primera versión impresa ''Traité sur les trois imposteurs'' (en francés) ha sido atribuida al impresor M. M. Rey, aunque probablemente existieran versiones manuscritas previas. |

||

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

==''Traité sur les trois imposteurs''== |

|||

The first printing of ''Traité sur les trois imposteurs'' was accredited to the printer M.M. Rey, but may have existed in manuscript form for some time before it was published. The first trace we have of it as a manuscript comes from a letter to [[Prosper Marchand]] from his old friend, Fritsch. He reminds Marchand about how another friend, Charles Levier, got the manuscript of the treatise from the library of [[Benjamin Furly]] in 1711. This gives a clue as to the provenance of the manuscript, now all but confirmed, as the work of the Irish satirist and freethinker [[John Toland]] (Seán Ó Tuathaláin 1670–1722).{{Citation needed|date=September 2010}} Even if it is not by Toland, it is certainly from the early eighteenth century and traceable to Marchand's circle that included [[Jean Aymon]] and [[Jean Rousset|Rousset de Missy]] and these may have edited Toland's hoax manuscript. It is unlikely to have been around since the time of [[Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor|Frederick II]] which was part of the mythology of the manuscript. According to historian [[Silvia Berti]], the book was originally published as ''La Vie et L'Esprit de Spinosa'' (The Life and Spirit of Spinoza),containing both a biography of [[Benedict Spinoza]] and the anti-religious essay, and was later republished under the title ''Traité sur les trois imposteurs''. It is believed the author of the book may have been a young Dutch diplomat called [[Jan Vroesen]].<ref>See Berti's essay in ''Atheism from the Reformation to the Enlightenment'' edited by [[Michael Hunter (historian)|Michael Hunter]] and [[David Wootton]]. Clarendon, 1992. ISBN 0198227361</ref> |

The first printing of ''Traité sur les trois imposteurs'' was accredited to the printer M.M. Rey, but may have existed in manuscript form for some time before it was published. The first trace we have of it as a manuscript comes from a letter to [[Prosper Marchand]] from his old friend, Fritsch. He reminds Marchand about how another friend, Charles Levier, got the manuscript of the treatise from the library of [[Benjamin Furly]] in 1711. This gives a clue as to the provenance of the manuscript, now all but confirmed, as the work of the Irish satirist and freethinker [[John Toland]] (Seán Ó Tuathaláin 1670–1722).{{Citation needed|date=September 2010}} Even if it is not by Toland, it is certainly from the early eighteenth century and traceable to Marchand's circle that included [[Jean Aymon]] and [[Jean Rousset|Rousset de Missy]] and these may have edited Toland's hoax manuscript. It is unlikely to have been around since the time of [[Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor|Frederick II]] which was part of the mythology of the manuscript. According to historian [[Silvia Berti]], the book was originally published as ''La Vie et L'Esprit de Spinosa'' (The Life and Spirit of Spinoza),containing both a biography of [[Benedict Spinoza]] and the anti-religious essay, and was later republished under the title ''Traité sur les trois imposteurs''. It is believed the author of the book may have been a young Dutch diplomat called [[Jan Vroesen]].<ref>See Berti's essay in ''Atheism from the Reformation to the Enlightenment'' edited by [[Michael Hunter (historian)|Michael Hunter]] and [[David Wootton]]. Clarendon, 1992. ISBN 0198227361</ref> |

||

| Línea 20: | Línea 23: | ||

The book was republished in Cleveland in 1904 by an anonymous publisher under the pseudonym "Alcofribas Nasier the Later" (using an anagram of François Rabelais, minus the cedilla on the c, which [[Rabelais]] used to publish ''Pantagruel'') |

The book was republished in Cleveland in 1904 by an anonymous publisher under the pseudonym "Alcofribas Nasier the Later" (using an anagram of François Rabelais, minus the cedilla on the c, which [[Rabelais]] used to publish ''Pantagruel'') |

||

===Answer of Voltaire=== |

|||

In 1770, the great Enlightenment satirist [[Voltaire]], published a response to the hoax treatise entitled [[Épître à l'Auteur du Livre des Trois Imposteurs]], which contains one of his best-known quotations, "If God didn't exist, it would be necessary to invent Him." |

In 1770, the great Enlightenment satirist [[Voltaire]], published a response to the hoax treatise entitled [[Épître à l'Auteur du Livre des Trois Imposteurs]], which contains one of his best-known quotations, "If God didn't exist, it would be necessary to invent Him." |

||

This was responded to a century later by [[Mikhail Bakunin]], the anarchist political philosopher and activist, with "If God did exist it would be necessary to abolish him". |

This was responded to a century later by [[Mikhail Bakunin]], the anarchist political philosopher and activist, with "If God did exist it would be necessary to abolish him". |

||

--> |

--> |

||

== Véase también == |

|||

*[[Necronomicón]] |

|||

== Referencias == |

== Referencias == |

||

{{listaref}} |

{{listaref}} |

||

== Enlaces externos == |

== Enlaces externos == |

||

* [http://www.infidels.org/library/historical/unknown/three_impostors.html Texto completo] en |

* [http://www.infidels.org/library/historical/unknown/three_impostors.html Texto completo] en Infidels.org. |

||

* [http://classiques.uqac.ca/classiques/holbach_baron_d/trois_imposteurs/trois_imposteurs.pdf Texto completo] en Classiques des ciences sociales. |

|||

* [ |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20060504030649/http://www.hfac.uh.edu/gbrown/philosophers/leibniz/BritannicaPages/EmperorFriedrich-II/EmperorFriedrich-II.html Biografía de Federico II], en la ''Encyclopedia Britannica'' (sección «Lucha contra el Papado»). |

||

{{Control de autoridades}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Categoría:Engaños literarios]] |

[[Categoría:Engaños literarios]] |

||

[[Categoría:Libros críticos con la religión]] |

[[Categoría:Libros críticos con la religión]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Revisión actual - 18:16 29 sep 2023

El Tratado de los tres impostores (en latín, De tribus impostoribus), también conocido como El espíritu de Spinoza, es el nombre de una obra que niega las tres religiones abrahámicas. Los «tres impostores» del título serían Moisés, Cristo y Mahoma. En él se sostiene que los tres representantes de las grandes religiones abrahámicas han engañado a la humanidad imponiéndole las ideas de Dios, obligando al pueblo a creerlas sin permitirle examinarlas.[1]

¿Un mito?

[editar]La existencia del libro y la atribución a varios enemigos políticos y herejes fue un tema muy extendido desde los siglos XI al XVIII, cuando los bulos en Alemania y Francia llegaban a producir libros físicos.

- Gregorio IX (1239) atribuye la obra a Federico II Hohenstaufen.

- A mediados del siglo XI, Tomás de Cantimpré[2] atribuía la obra sobre los «tres impostores» al canónigo Simón de Tournai (circa 1184-1200).

- Thomas Browne (1543) atribuye la autoría a Bernardino Ochino.

- Algunas leyendas atribuyen la autoría a escritores judíos y musulmanes.[3]

De imposturis religionum

[editar]El origen del libro se encontraría en el texto De imposturis religionum, un ataque anónimo al cristianismo publicado en 1598 (aunque datado anteriormente por G. Bartsch), y que se dio a conocer en la subasta de la biblioteca del teólogo de Greifswald Johann Friedrich Mayer en 1716. A partir de este texto el jurista Johannes Joachim Müller (1661–1733) escribió dos textos más, contra Moisés y contra Mahoma, publicando los tres textos de forma conjunta en 1753 como De Tribus Impostoribus. El primer rastro del libro se encuentra en un manuscrito de Prosper Marchand, una carta a su amigo Fritsch. En ella, Marchand recuerda a Fritsch cómo otro amigo común, Benjamin Furly, había obtenido la obra de una biblioteca en 1711. La primera versión impresa Traité sur les trois imposteurs (en francés) ha sido atribuida al impresor M. M. Rey, aunque probablemente existieran versiones manuscritas previas.

Referencias

[editar]- ↑ Critchley, Simon (2016). Apuntes sobre el suicidio (1.ª edición). Alpha Decay. p. 27. ISBN 978-84-944896-2-4. OCLC 957749337. Consultado el 22 de febrero de 2021.

- ↑ Thomas de Cantimpré, De apibus. Véase el artículo, firmado por P. R. sobre Simón de Tournai en Histoire littéraire de la France, t. 16, Paris, 1824, pp. 390-391, consultable en Google Libros.

- ↑ Artículo sobre «Averroes», en la Jewish Encyclopedia.

Enlaces externos

[editar]- Texto completo en Infidels.org.

- Texto completo en Classiques des ciences sociales.

- Biografía de Federico II, en la Encyclopedia Britannica (sección «Lucha contra el Papado»).