Diferencia entre revisiones de «Distribución estable»

Página creada con «{{Ficha de distribución de probabilidad |nombre = Distribuciones estables |pdf_image = 325px|Distribuciones estables simétricas<br />...» |

Sin resumen de edición |

||

| (No se muestran 15 ediciones intermedias de 11 usuarios) | |||

| Línea 20: | Línea 20: | ||

|car = <math>\exp\!\Big[\; it\mu - |c\,t|^\alpha\,(1-i \beta\,\mbox{sgn}(t)\Phi) \;\Big],</math><br> donde <math>\Phi = \begin{cases} \tan\tfrac{\pi\alpha}{2} & \text{if }\alpha \ne 1 \\ -\tfrac{2}{\pi}\log|t| & \text{if }\alpha = 1 \end{cases}</math> |

|car = <math>\exp\!\Big[\; it\mu - |c\,t|^\alpha\,(1-i \beta\,\mbox{sgn}(t)\Phi) \;\Big],</math><br> donde <math>\Phi = \begin{cases} \tan\tfrac{\pi\alpha}{2} & \text{if }\alpha \ne 1 \\ -\tfrac{2}{\pi}\log|t| & \text{if }\alpha = 1 \end{cases}</math> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

En [[teoría de la probabilidad]], una [[distribución de probabilidad|distribución]] se denomina '''estable''' (o una [[variable aleatoria se denomina '''estable''') si es una [[combinación lineal]] de dos o más copias [[independencia (probabilidad)|independientes]] de una muestra aleatoria que tiene la misma distribución de probabilidad, salvo por quizá algún [[parámetro de localización]] o [[ |

En [[teoría de la probabilidad]], una [[distribución de probabilidad|distribución]] se denomina '''estable''' (o una [[variable aleatoria]] se denomina '''estable''') si es una [[combinación lineal]] de dos o más copias [[independencia (probabilidad)|independientes]] de una muestra aleatoria que tiene la misma distribución de probabilidad, salvo por quizá algún [[Parámetro_de_ubicación|parámetro de localización]] o [[Parámetro_de_escala| escala]]. |

||

La familia de distribuciones estables a veces se denomina también '''distribución α-estable de Lévy''', en honor a [[Paul Lévy]], el |

La familia de distribuciones estables a veces se denomina también '''distribución α-estable de Lévy''', en honor a [[Paul Lévy]], el primero en estudiar este tipo de distribuciones.<ref name="BM 1960">B. Mandelbrot, [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2525289 "The Pareto-Lévy Law and the Distribution of Income"], ''International Economic Review'' 1960</ref><ref>Paul Lévy, ''Calcul des probabilités'', 1925.</ref> |

||

De los cuatro parámetros que definen una distribución estable, el más significativo es el parámetro de estabilidad, α (ver ficha lateral). Las distribuciones estables satisfacen que 0 < α ≤ 2, correspondiendo el valor máximo con una [[distribución normal]] (que es el caso más sencillo de distribución estable). El valor α = 1 corresponde a la [[distribución de Cauchy]]. Las distribuciones estables no tienen una [[varianza]] finita si α < 2, más aún si α ≤ 1 ni siquiera tienen [[valor esperado|media]] finita. La importancia práctica de las distribuciones estables es que son "atractores" para la distribución de sumas de variables aleatorias independientes e idénticamente distribuidas (que además pertenecen a [[espacios Lp]]). La distribución normal define una subfamilia de distribuciones estables. Por el clásico [[teorema del límite central]] la suma de un conjunto de variables con idéntica distribución e independientes y que además tenga varianza finita, tenderá a una distribución normal a medida que el número de variables que interviene en la suma crece. Sin la restricción de varianza finita, el teorema del límite central no será aplicable, pero la suma de esas variables tenderá hacia una distribución estable (α < 2). |

|||

<!--Of the four parameters defining the family, most attention has been focused on the stability parameter, α (see panel). Stable distributions have 0 < α ≤ 2, with the upper bound corresponding to the [[normal distribution]], and α = 1 to the [[Cauchy distribution]]. The distributions have undefined [[variance]] for α < 2, and undefined [[mean]] for α ≤ 1. The importance of stable probability distributions is that they are "attractors" for properly normed sums of independent and identically-distributed ([[iid]]) random variables. The normal distribution defines a family of stable distributions. By the classical [[central limit theorem]] the properly normed sum of a set of random variables, each with finite variance, will tend towards a normal distribution as the number of variables increases. Without the finite variance assumption the limit may be a stable distribution. [[Benoit Mandelbrot|Mandelbrot]] referred to stable distributions that are non-normal as "stable Paretian distributions",<ref>B.Mandelbrot, Stable Paretian Random Functions and the Multiplicative Variation of Income, Econometrica 1961 http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/1911802.pdf</ref><ref>B. Mandelbrot, The variation of certain Speculative Prices, The Journal of Business 1963 [http://web.williams.edu/Mathematics/sjmiller/public_html/341Fa09/econ/Mandelbroit_VariationCertainSpeculativePrices.pdf]</ref><ref>Eugene F. Fama, Mandelbrot and the Stable Paretian Hypothesis, The Journal of Business 1963</ref> after [[Vilfredo Pareto]]. Mandelbrot referred to "positive" stable distributions (meaning maximally skewed in the positive direction) with 1<α<2 as "Pareto-Levy distributions".<ref name="BM 1960"/> He also regarded this range as relevant for the description of stock and commodity prices. |

|||

[[Benoit Mandelbrot|Mandelbrot]] denominó a las distribuciones estables con α < 2 como "distribuciones estables paretianas",<ref>B.Mandelbrot, Stable Paretian Random Functions and the Multiplicative Variation of Income, Econometrica 1961 http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/1911802.pdf</ref><ref>B. Mandelbrot, The variation of certain Speculative Prices, The Journal of Business 1963 [http://web.williams.edu/Mathematics/sjmiller/public_html/341Fa09/econ/Mandelbroit_VariationCertainSpeculativePrices.pdf]</ref><ref>Eugene F. Fama, Mandelbrot and the Stable Paretian Hypothesis, The Journal of Business 1963</ref> por [[Vilfredo Pareto]]. Mandelbrot usó el término para distribuciones estables "positivas" (es decir, máximamente asimétricas hacia la dirección positiva) con 1<α<2 como "distribuciones de Pareto-Lévy".<ref name="BM 1960"/> Además consideró que estas últimas eran relevantes para describir los precios de acciones y productos de consumo. |

|||

==Definition== |

|||

A non-[[degenerate distribution]] is a stable distribution if it satisfies the following property: |

|||

==Definición== |

|||

:Let ''X''<sub>1</sub> and ''X''<sub>2</sub> be independent copies of a [[random variable]] ''X''. Then ''X'' is said to be '''stable''' if for any constants ''a'' > 0 and ''b'' > 0 the random variable ''aX''<sub>1</sub> + ''bX''<sub>2</sub> has the same distribution as ''cX'' + ''d'' for some constants ''c'' > 0 and ''d''. The distribution is said to be ''strictly stable'' if this holds with ''d'' = 0.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url = http://academic2.american.edu/~jpnolan/stable/chap1.pdf|title = Stable Distributions - Models for Heavy Tailed Data|date = |accessdate = 2009-02-21|website = |publisher = |last = Nolan|first = John P.}}</ref> |

|||

Una [[distribución degenerada|distribución no degenerada]] es estable si satisface la siguiente propiedad: |

|||

:Sean ''X''<sub>1</sub> y ''X''<sub>2</sub> dos copias de una [[variable aleatoria]] ''X'' (es decir, dos instancias de variables aleatorias independientes, de variables que tienen la misma distribución que ''X''). Entonces ''X'' se denomina '''estable''' si existen dos constantes ''a'' > 0 y ''b'' > 0 tales que la nueva variable aleatoria ''aX''<sub>1</sub> + ''bX''<sub>2</sub> tenga la misma distribución que ''cX'' + ''d'' para otras dos constantes ''c'' > 0 y ''d''. La distribución se llama ''estictamente estable'' si esto sigue siendo cierto aún con ''d'' = 0.<ref name=":0">{{cita web|url = http://academic2.american.edu/~jpnolan/stable/chap1.pdf|título = Stable Distributions - Models for Heavy Tailed Data|fecha = |fechaacceso = 21 de febrero de 2009|website = |editorial = |apellido = Nolan|nombre = John P.|fechaarchivo = 17 de julio de 2011|urlarchivo = https://web.archive.org/web/20110717003439/http://academic2.american.edu/~jpnolan/stable/chap1.pdf|deadurl = yes}}</ref> |

|||

Since the [[normal distribution]], the [[Cauchy distribution]], and the [[Lévy distribution]] all have the above property, it follows that they are special cases of stable distributions. |

|||

Puesto que la [[distribución normal]], la [[distribución de Cauchy]] y la [[distribución de Lévy]] satisfacen esta propiedad, son casos particulares de distribuciones estables. Más aún, Lévy demostró que el conjunto de todas las distribuciones estables puede representarse como una familia dada por cuatro parámetros de distribuciones continuas. Dos de los parámetros representan el parámetro de localización μ y el factor de escala ''c'', mientras que los otros dos β y α, se corresponden con el grado de asimetría y concentración (ver gráficas de la ficha lateral). |

|||

Such distributions form a four-parameter family of continuous [[probability distribution]]s parametrized by location and scale parameters μ and ''c'', respectively, and two shape parameters β and α, roughly corresponding to measures of asymmetry and concentration, respectively (see the figures). |

|||

Aunque la [[densidad de probabilidad]] de estas distribuciones estables no admite una fórmula analítica cerrada (expresable en términos de [[función elemental|funciones elementales]]), sin embargo, su [[función característica]] si admite una fórmula analítica cerrada. Cualquier distribución de probaiblidad dada por la [[transformada de Fourier]] de una [[función característica]] φ(''t'') del tipo: |

|||

Although the probability density function for a general stable distribution cannot be written analytically, the general characteristic function can be. Any probability distribution is given by the [[Fourier transform]] of its [[Characteristic function (probability theory)|characteristic function]] φ(''t'') by: |

|||

{{ecuación| |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

||left}} |

|||

| ⚫ | Una variable aleatoria ''X'' es estable si su función característica puede escribirse como<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1">{{cita libro|título = The Statistical Mechanics of Financial Markets - Springer|url = http://link.springer.com/10.1007/b137351|doi = 10.1007/b137351|apellido = Voit|nombre = Johannes|editorial = Springer|año = 2005}}</ref> |

||

{{ecuación| |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

||left}} |

|||

donde sgn(''t'') es simplemente la [[función signo]] de ''t'' y Φ viene dada por |

|||

{{ecuación| |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

||left}} |

|||

para todo α, excepto α = 1, en cuyo caso: |

|||

{{ecuación| |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

||left}} |

|||

μ ∈ '''R''' es un parámetro de localización y β ∈ [−1, 1] se denomina ''parámetro de asimetría''. Nótese que en este contexto la [[Asimetría estadística|asimetría "usual"]] no está bien definida, cuando α < 2 ya que la distribución no admite moments de segundo orden ni superiores (pero la asimetría usual usa en su definición el tercer [[momento central]]). |

|||

La razón de que una distribución que satisface las condiciones anteriores sea estable es que la función característica para la suma de dos variables aleatorias es igual al producto de las correspondientes funciones características. Al sumar dos variables aleatorias que tienen una distribución estable se obtiene otra variable con los mismos valores de α y β, pero posiblemente valores diferentes de μ y ''c'' (cambia la localización y la escala, pero no la el parámetro de estabilidad ni el parámetro de asimetría). |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

No cualquier función es la función característica de una distribución de probabilidad legítima, ya que una función de distribución real varía entre 0 y 1 son decrecer, pero la función caractecterística dada anteriormente podría no ser adecuada si los pámetros no están dentro del rango adecuado. El valor de la función característica para cierto valor ''t'' es el complejo conjugado de su valor en −''t'' como debería ser para que una función de distribución sea real. En el caso más sencillo β = 0, la función característica es simplemente una [[función exponencial estirada]], la distribución es simétrica alrededor de μ y en ese caso se denomina '''distribución α-estable simétrica de Lévy''', frecuentemente abreviada como ''S''α''S''. Cuando α < 1 y β = 1, la distribución tiene un [[Soporte (matemáticas)|soporte]] en [μ, ∞). El parámetro ''c'' > 0 es un factor de escala que mide el ancho típico de la distribución mientras que α es el exponente o índice de la distribución que especifica el comportamiento asintótico de dicha distribución. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

where sgn(''t'') is just the [[sign function|sign]] of ''t'' and Φ is given by |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

for all α except α = 1 in which case: |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

μ ∈ '''R''' is a shift parameter, β ∈ [−1, 1], called the ''skewness parameter'', is a measure of asymmetry. Notice that in this context the usual [[skewness]] is not well defined, as for α < 2 the distribution does not admit 2nd or higher [[moment (mathematics)|moments]], and the usual skewness definition is the 3rd [[central moment]]. |

|||

The reason this gives a stable distribution is that the characteristic function for the sum of two random variables equals the product of the two corresponding characteristic functions. Adding two random variables from a stable distribution gives something with the same values of α and β, but possibly different values of μ and ''c''. |

|||

Not every function is the characteristic function of a legitimate probability distribution (that is, one whose cumulative distribution function is real and goes from 0 to 1 without decreasing), but the characteristic functions given above will be legitimate so long as the parameters are in their ranges. The value of the characteristic function at some value ''t'' is the complex conjugate of its value at −''t'' as it should be so that the probability distribution function will be real. |

|||

In the simplest case β = 0, the characteristic function is just a [[stretched exponential function]]; the distribution is symmetric about μ and is referred to as a (Lévy) '''symmetric alpha-stable distribution''', often abbreviated ''S''α''S''. |

|||

When α < 1 and β = 1, the distribution is supported by [μ, ∞). |

|||

The parameter ''c'' > 0 is a scale factor which is a measure of the width of the distribution while α is the exponent or index of the distribution and specifies the asymptotic behavior of the distribution. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The above definition is only one of the parametrizations in use for stable distributions; it is the most common but is not continuous in the parameters at {{math|α {{=}} 1}}. |

The above definition is only one of the parametrizations in use for stable distributions; it is the most common but is not continuous in the parameters at {{math|α {{=}} 1}}. |

||

| Línea 189: | Línea 183: | ||

* For α = 1/2 and β = 1 the distribution reduces to a [[Lévy distribution]] with scale parameter ''c'' and shift parameter μ. |

* For α = 1/2 and β = 1 the distribution reduces to a [[Lévy distribution]] with scale parameter ''c'' and shift parameter μ. |

||

Note that the above three distributions are also connected, in the following way: A standard Cauchy random variable can be viewed as a [[Compound probability distribution|mixture]] of Gaussian random variables (all with mean zero), with the variance being drawn from a standard Lévy distribution. And in fact this is a special case of a more general theorem |

Note that the above three distributions are also connected, in the following way: A standard Cauchy random variable can be viewed as a [[Compound probability distribution|mixture]] of Gaussian random variables (all with mean zero), with the variance being drawn from a standard Lévy distribution. And in fact this is a special case of a more general theorem<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|title = Continuous and discrete properties of stochastic processes|last = Lee|first = Wai Ha|publisher = PhD thesis, University of Nottingham|year = 2010|isbn = |location = |pages = |url = http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11194/}}</ref> which allows any symmetric alpha-stable distribution to be viewed in this way (with the alpha parameter of the mixture distribution equal to twice the alpha parameter of the mixing distribution—and the beta parameter of the mixing distribution always equal to one). |

||

A general closed form expression for stable PDF's with rational values of α is available in terms of [[Meijer G-function]]s.<ref>{{Cite journal|title = On Representation of Densities of Stable Laws by Special Functions|url = http://epubs.siam.org/doi/abs/10.1137/1139025|journal = Theory of Probability & Its Applications|date = 1995|issn = 0040-585X|pages = 354–362|volume = 39|issue = 2|doi = 10.1137/1139025|first = V.|last = Zolotarev}}</ref> Fox H-Functions can also be used to express the stable probability density functions. For simple rational numbers, the closed form expression is often in terms of less complicated [[special functions]]. Several closed form expressions having rather simple expressions in terms of special functions are available. In the table below, PDF's expressible by elementary functions are indicated by an ''E'' and those that are expressible by special functions are indicated by an ''s''.<ref name=":2" /> |

A general closed form expression for stable PDF's with rational values of α is available in terms of [[Meijer G-function]]s.<ref>{{Cite journal|title = On Representation of Densities of Stable Laws by Special Functions|url = http://epubs.siam.org/doi/abs/10.1137/1139025|journal = Theory of Probability & Its Applications|date = 1995|issn = 0040-585X|pages = 354–362|volume = 39|issue = 2|doi = 10.1137/1139025|first = V.|last = Zolotarev}}</ref> Fox H-Functions can also be used to express the stable probability density functions. For simple rational numbers, the closed form expression is often in terms of less complicated [[special functions]]. Several closed form expressions having rather simple expressions in terms of special functions are available. In the table below, PDF's expressible by elementary functions are indicated by an ''E'' and those that are expressible by special functions are indicated by an ''s''.<ref name=":2" /> |

||

| Línea 229: | Línea 223: | ||

== Simulation of stable variables == |

== Simulation of stable variables == |

||

Simulating sequences of stable random variables is not straightforward, since there are no analytic expressions for the inverse <math>F^{-1}(x)</math> nor the CDF <math>F(x)</math> itself.<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Numerical calculation of stable densities and distribution functions|url = http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15326349708807450|journal = Communications in Statistics. Stochastic Models|date = 1997|issn = 0882-0287|pages = 759–774|volume = 13|issue = 4|doi = 10.1080/15326349708807450|first = John P.|last = Nolan}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title = Some Improvements in Numerical Evaluation of Symmetric Stable Density and Its Derivatives|url = http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03610920500439729|journal = Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods|date = 2006|issn = 0361-0926|pages = 149–172|volume = 35|issue = 1|doi = 10.1080/03610920500439729|first = Muneya|last = Matsui|first2 = Akimichi|last2 = Takemura}}</ref> All standard approaches like the rejection or the inversion methods would require tedious computations. A much more elegant and efficient solution was proposed by Chambers, Mallows and Stuck (CMS),<ref>{{Cite journal|title = A Method for Simulating Stable Random Variables|url = http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01621459.1976.10480344|journal = Journal of the American Statistical Association|date = 1976|issn = 0162-1459|pages = 340–344|volume = 71|issue = 354|doi = 10.1080/01621459.1976.10480344|first = J. M.|last = Chambers|first2 = C. L.|last2 = Mallows|first3 = B. W.|last3 = Stuck}}</ref> who noticed that a certain integral formula<ref>{{Cite book|title = One-Dimensional Stable Distributions|last = Zolotarev|first = V. M.|publisher = American Mathematical Society|year = 1986|isbn = 978-0-8218-4519-6|location = |pages = }}</ref> yielded the following algorithm:<ref>{{Cite book|title = Heavy-Tailed Distributions in VaR Calculations|url = http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-21551-3_34|publisher = Springer Berlin Heidelberg|date = 2012|isbn = 978-3-642-21550-6|pages = 1025–1059|series = Springer Handbooks of Computational Statistics|doi = 10.1007/978-3-642-21551-3_34|first = Adam|last = Misiorek|first2 = Rafał|last2 = Weron|editor-first = James E.|editor-last = Gentle|editor-first2 = Wolfgang Karl|editor-last2 = Härdle|editor-first3 = Yuichi|editor-last3 = Mori}}</ref> |

Simulating sequences of stable random variables is not straightforward, since there are no analytic expressions for the inverse <math>F^{-1}(x)</math> nor the CDF <math>F(x)</math> itself.<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Numerical calculation of stable densities and distribution functions|url = http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15326349708807450|journal = Communications in Statistics. Stochastic Models|date = 1997|issn = 0882-0287|pages = 759–774|volume = 13|issue = 4|doi = 10.1080/15326349708807450|first = John P.|last = Nolan}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title = Some Improvements in Numerical Evaluation of Symmetric Stable Density and Its Derivatives|url = http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03610920500439729|journal = Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods|date = 2006|issn = 0361-0926|pages = 149–172|volume = 35|issue = 1|doi = 10.1080/03610920500439729|first = Muneya|last = Matsui|first2 = Akimichi|last2 = Takemura}}</ref> All standard approaches like the rejection or the inversion methods would require tedious computations. A much more elegant and efficient solution was proposed by Chambers, Mallows and Stuck (CMS),<ref>{{Cite journal|title = A Method for Simulating Stable Random Variables|url = http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01621459.1976.10480344|journal = Journal of the American Statistical Association|date = 1976|issn = 0162-1459|pages = 340–344|volume = 71|issue = 354|doi = 10.1080/01621459.1976.10480344|first = J. M.|last = Chambers|first2 = C. L.|last2 = Mallows|first3 = B. W.|last3 = Stuck}}</ref> who noticed that a certain integral formula<ref>{{Cite book|title = One-Dimensional Stable Distributions|url = https://archive.org/details/onedimensionalst00zolo_0|last = Zolotarev|first = V. M.|publisher = American Mathematical Society|year = 1986|isbn = 978-0-8218-4519-6|location = |pages = }}</ref> yielded the following algorithm:<ref>{{Cite book|title = Heavy-Tailed Distributions in VaR Calculations|url = http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-21551-3_34|publisher = Springer Berlin Heidelberg|date = 2012|isbn = 978-3-642-21550-6|pages = 1025–1059|series = Springer Handbooks of Computational Statistics|doi = 10.1007/978-3-642-21551-3_34|first = Adam|last = Misiorek|first2 = Rafał|last2 = Weron|editor-first = James E.|editor-last = Gentle|editor-first2 = Wolfgang Karl|editor-last2 = Härdle|editor-first3 = Yuichi|editor-last3 = Mori}}</ref> |

||

* generate a random variable <math>U</math> uniformly distributed on <math>(-\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2})</math> and an independent exponential random variable <math>W</math> with mean 1; |

* generate a random variable <math>U</math> uniformly distributed on <math>(-\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2})</math> and an independent exponential random variable <math>W</math> with mean 1; |

||

* for <math>\alpha\ne 1</math> compute: |

* for <math>\alpha\ne 1</math> compute: |

||

| Línea 266: | Línea 260: | ||

\end{cases}</math> |

\end{cases}</math> |

||

is <math>S_\alpha(\beta,c,\mu)</math>. It is interesting to note that for <math>\alpha=2</math> (and <math>\beta=0</math>) the CMS method reduces to the well known [[Box–Muller transform|Box-Muller transform]] for generating [[Normal distribution|Gaussian]] random variables.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Simulation and Chaotic Behavior of Alpha-stable Stochastic Processes|last = Janicki|first = Aleksander|publisher = CRC Press|year = 1994|isbn = 9780824788827|location = |pages = |url = https://www.crcpress.com/Simulation-and-Chaotic-Behavior-of-Alpha-stable-Stochastic-Processes/Janicki-Weron/9780824788827|last2 = Weron|first2 = Aleksander}}</ref> Many other approaches have been proposed in the literature, including application of Bergström and LePage series expansions, see |

is <math>S_\alpha(\beta,c,\mu)</math>. It is interesting to note that for <math>\alpha=2</math> (and <math>\beta=0</math>) the CMS method reduces to the well known [[Box–Muller transform|Box-Muller transform]] for generating [[Normal distribution|Gaussian]] random variables.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Simulation and Chaotic Behavior of Alpha-stable Stochastic Processes|last = Janicki|first = Aleksander|publisher = CRC Press|year = 1994|isbn = 9780824788827|location = |pages = |url = https://www.crcpress.com/Simulation-and-Chaotic-Behavior-of-Alpha-stable-Stochastic-Processes/Janicki-Weron/9780824788827|last2 = Weron|first2 = Aleksander}}</ref> Many other approaches have been proposed in the literature, including application of Bergström and LePage series expansions, see<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Fast, accurate algorithm for numerical simulation of L\'evy stable stochastic processes|url = http://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevE.49.4677|journal = Physical Review E|date = 1994|pages = 4677–4683|volume = 49|issue = 5|doi = 10.1103/PhysRevE.49.4677|first = Rosario Nunzio|last = Mantegna}}</ref> and,<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Computer investigation of the Rate of Convergence of Lepage Type Series to α-Stable Random Variables|url = http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02331889208802383|journal = Statistics|date = 1992|issn = 0233-1888|pages = 365–373|volume = 23|issue = 4|doi = 10.1080/02331889208802383|first = Aleksander|last = Janicki|first2 = Piotr|last2 = Kokoszka}}</ref> respectively. However, the CMS method is regarded as the fastest and the most accurate. |

||

== Applications == |

== Applications == |

||

| Línea 300: | Línea 294: | ||

:<math>f\biggl(x;\frac{1}{2},0,1,0\biggr) = \frac{\vert x \vert^{-3/2}}{{\sqrt{2\pi}}}\Biggl(\sin\left(\frac{1}{4\vert x \vert}\right)\Biggl[\frac{1}{2}-S\biggl(\sqrt{\frac{1}{2\pi\vert x \vert}}\biggr)\Biggr]+\cos\left(\frac{1}{4\vert x \vert}\right)\Biggl[\frac{1}{2}-C\biggl(\sqrt{\frac{1}{2\pi\vert x \vert}}\biggr)\Biggr]\Biggr)</math> |

:<math>f\biggl(x;\frac{1}{2},0,1,0\biggr) = \frac{\vert x \vert^{-3/2}}{{\sqrt{2\pi}}}\Biggl(\sin\left(\frac{1}{4\vert x \vert}\right)\Biggl[\frac{1}{2}-S\biggl(\sqrt{\frac{1}{2\pi\vert x \vert}}\biggr)\Biggr]+\cos\left(\frac{1}{4\vert x \vert}\right)\Biggl[\frac{1}{2}-C\biggl(\sqrt{\frac{1}{2\pi\vert x \vert}}\biggr)\Biggr]\Biggr)</math> |

||

where <math>S(x)</math> and <math>C(x)</math> are [[Fresnel Integrals]]. |

where <math>S(x)</math> and <math>C(x)</math> are [[Fresnel Integrals]].<ref name="Hopcraft1999">{{cite journal |last=Hopcraft |first=K. I. |last2=Jakeman |first2=E.|last3=Tanner|first3=R. M. J. |date=1999 |title=Lévy random walks with fluctuating step number and multiscale behavior |url= |journal=Physical Review E |publisher= |volume=60 |issue=5 |pages=5327-5343 |doi= }}</ref> |

||

:<math>f\biggl(x;\frac{2}{3},0,1,0\biggr) = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{3\pi}}\vert x \vert ^ {-1} \exp\biggl(\frac{2}{27}x^{-2}\biggr) W_{-1/2,1/6}\biggl(\frac{4}{27}x^{-2}\biggr)</math> |

:<math>f\biggl(x;\frac{2}{3},0,1,0\biggr) = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{3\pi}}\vert x \vert ^ {-1} \exp\biggl(\frac{2}{27}x^{-2}\biggr) W_{-1/2,1/6}\biggl(\frac{4}{27}x^{-2}\biggr)</math> |

||

| ⚫ | where <math>W_{k,\mu}(z)</math> is a [[Whittaker function]].<ref name="Zolotarev1999">{{cite journal |last=Uchaikin |first=V. V. |last2=Zolotarev |first2=V. M. |date=1999 |title=Chance And Stability - Stable Distributions And Their Applications |url= |journal=VSP |publisher= |volume= |issue= |pages= |doi= |location=Utrecht, Netherlands}}</ref> |

||

where <math>W_{k,\mu}(z)</math> is a [[Whittaker function]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

:<math> |

:<math> |

||

| Línea 364: | Línea 357: | ||

*[[Multivariate stable distribution]] |

*[[Multivariate stable distribution]] |

||

*[[Discrete-stable distribution]]--> |

*[[Discrete-stable distribution]]--> |

||

==Referencias== |

==Referencias== |

||

{{listaref|2}} |

{{listaref|2}} |

||

===Enlaces externos === |

===Enlaces externos === |

||

* The STABLE program for Windows is available from John Nolan's stable webpage: http://academic2.american.edu/~jpnolan/stable/stable.html. It calculates the density (pdf), cumulative distribution function (cdf) and quantiles for a general stable distribution, and performs maximum likelihood estimation of stable parameters and some exploratory data analysis techniques for assessing the fit of a data set. |

* The STABLE program for Windows is available from John Nolan's stable webpage: http://academic2.american.edu/~jpnolan/stable/stable.html {{Wayback|url=http://academic2.american.edu/~jpnolan/stable/stable.html |date=20061030061441 }}. It calculates the density (pdf), cumulative distribution function (cdf) and quantiles for a general stable distribution, and performs maximum likelihood estimation of stable parameters and some exploratory data analysis techniques for assessing the fit of a data set. |

||

* [[MATLAB|Matlab]] codes for simulation of stable variables and estimation of stable parameters are available from RePEc: https://ideas.repec.org/e/pwe42.html#software |

* [[MATLAB|Matlab]] codes for simulation of stable variables and estimation of stable parameters are available from RePEc: https://ideas.repec.org/e/pwe42.html#software |

||

{{ProbDistributions|continuous-infinite}} |

|||

{{ORDENAR:Estables}} |

{{ORDENAR:Estables}} |

||

{{Control de autoridades}} |

|||

[[Categoría:Distribuciones continuas]] |

[[Categoría:Distribuciones continuas]] |

||

[[Categoría:Paul Pierre Lévy]] |

|||

Revisión actual - 00:38 3 nov 2024

| Distribuciones estables | ||

|---|---|---|

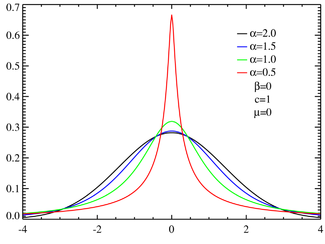

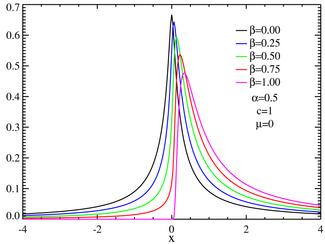

Distribución α-estable simétrica con factor de escala unitario  Distribuciones estables asimétricas centradas con factor de escala unitario Función de densidad de probabilidad | ||

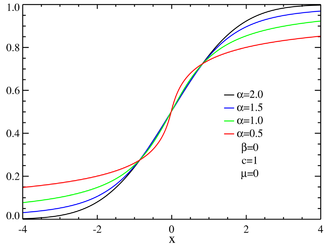

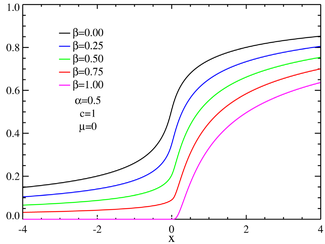

Función de distribución para las distribuciones α-estables simétricas  Función de distribución para distribuciones estables asimétricas Función de distribución de probabilidad | ||

| Parámetros |

α ∈ (0, 2] — parámetro de estabilidad | |

| Dominio | x ∈ R, o x ∈ [μ, +∞) si α < 1 y β = 1, o x ∈ (-∞, μ] si α < 1 y β = −1 | |

| Función de densidad (pdf) | no hay forma analítica explícita, excepto para algunos valores de los parámetros | |

| Función de distribución (cdf) | no hay forma analítica explícita, excepto para algunos valores de los parámetros | |

| Media | μ cuando α > 1 y no definida en el resto de casos | |

| Mediana | μ cuando β = 0 y no definida en el resto de casos | |

| Moda | μ cuando β = 0 y no definida en el resto de casos | |

| Varianza | 2c2 cuando α = 2, para otros casos no es finita | |

| Coeficiente de simetría | 0 cuando α = 2, para otros casos no es finita | |

| Curtosis | 0 when α = 2, para otros casos no es finita | |

| Entropía | no hay forma analítica explícita, excepto para algunos valores de los parámetros | |

| Función generadora de momentos (mgf) | no definida | |

| Función característica |

donde | |

En teoría de la probabilidad, una distribución se denomina estable (o una variable aleatoria se denomina estable) si es una combinación lineal de dos o más copias independientes de una muestra aleatoria que tiene la misma distribución de probabilidad, salvo por quizá algún parámetro de localización o escala.

La familia de distribuciones estables a veces se denomina también distribución α-estable de Lévy, en honor a Paul Lévy, el primero en estudiar este tipo de distribuciones.[1][2]

De los cuatro parámetros que definen una distribución estable, el más significativo es el parámetro de estabilidad, α (ver ficha lateral). Las distribuciones estables satisfacen que 0 < α ≤ 2, correspondiendo el valor máximo con una distribución normal (que es el caso más sencillo de distribución estable). El valor α = 1 corresponde a la distribución de Cauchy. Las distribuciones estables no tienen una varianza finita si α < 2, más aún si α ≤ 1 ni siquiera tienen media finita. La importancia práctica de las distribuciones estables es que son "atractores" para la distribución de sumas de variables aleatorias independientes e idénticamente distribuidas (que además pertenecen a espacios Lp). La distribución normal define una subfamilia de distribuciones estables. Por el clásico teorema del límite central la suma de un conjunto de variables con idéntica distribución e independientes y que además tenga varianza finita, tenderá a una distribución normal a medida que el número de variables que interviene en la suma crece. Sin la restricción de varianza finita, el teorema del límite central no será aplicable, pero la suma de esas variables tenderá hacia una distribución estable (α < 2).

Mandelbrot denominó a las distribuciones estables con α < 2 como "distribuciones estables paretianas",[3][4][5] por Vilfredo Pareto. Mandelbrot usó el término para distribuciones estables "positivas" (es decir, máximamente asimétricas hacia la dirección positiva) con 1<α<2 como "distribuciones de Pareto-Lévy".[1] Además consideró que estas últimas eran relevantes para describir los precios de acciones y productos de consumo.

Definición

[editar]Una distribución no degenerada es estable si satisface la siguiente propiedad:

- Sean X1 y X2 dos copias de una variable aleatoria X (es decir, dos instancias de variables aleatorias independientes, de variables que tienen la misma distribución que X). Entonces X se denomina estable si existen dos constantes a > 0 y b > 0 tales que la nueva variable aleatoria aX1 + bX2 tenga la misma distribución que cX + d para otras dos constantes c > 0 y d. La distribución se llama estictamente estable si esto sigue siendo cierto aún con d = 0.[6]

Puesto que la distribución normal, la distribución de Cauchy y la distribución de Lévy satisfacen esta propiedad, son casos particulares de distribuciones estables. Más aún, Lévy demostró que el conjunto de todas las distribuciones estables puede representarse como una familia dada por cuatro parámetros de distribuciones continuas. Dos de los parámetros representan el parámetro de localización μ y el factor de escala c, mientras que los otros dos β y α, se corresponden con el grado de asimetría y concentración (ver gráficas de la ficha lateral).

Aunque la densidad de probabilidad de estas distribuciones estables no admite una fórmula analítica cerrada (expresable en términos de funciones elementales), sin embargo, su función característica si admite una fórmula analítica cerrada. Cualquier distribución de probaiblidad dada por la transformada de Fourier de una función característica φ(t) del tipo:

Una variable aleatoria X es estable si su función característica puede escribirse como[6][7]

donde sgn(t) es simplemente la función signo de t y Φ viene dada por

para todo α, excepto α = 1, en cuyo caso:

μ ∈ R es un parámetro de localización y β ∈ [−1, 1] se denomina parámetro de asimetría. Nótese que en este contexto la asimetría "usual" no está bien definida, cuando α < 2 ya que la distribución no admite moments de segundo orden ni superiores (pero la asimetría usual usa en su definición el tercer momento central).

La razón de que una distribución que satisface las condiciones anteriores sea estable es que la función característica para la suma de dos variables aleatorias es igual al producto de las correspondientes funciones características. Al sumar dos variables aleatorias que tienen una distribución estable se obtiene otra variable con los mismos valores de α y β, pero posiblemente valores diferentes de μ y c (cambia la localización y la escala, pero no la el parámetro de estabilidad ni el parámetro de asimetría).

No cualquier función es la función característica de una distribución de probabilidad legítima, ya que una función de distribución real varía entre 0 y 1 son decrecer, pero la función caractecterística dada anteriormente podría no ser adecuada si los pámetros no están dentro del rango adecuado. El valor de la función característica para cierto valor t es el complejo conjugado de su valor en −t como debería ser para que una función de distribución sea real. En el caso más sencillo β = 0, la función característica es simplemente una función exponencial estirada, la distribución es simétrica alrededor de μ y en ese caso se denomina distribución α-estable simétrica de Lévy, frecuentemente abreviada como SαS. Cuando α < 1 y β = 1, la distribución tiene un soporte en [μ, ∞). El parámetro c > 0 es un factor de escala que mide el ancho típico de la distribución mientras que α es el exponente o índice de la distribución que especifica el comportamiento asintótico de dicha distribución.

Referencias

[editar]- ↑ a b B. Mandelbrot, "The Pareto-Lévy Law and the Distribution of Income", International Economic Review 1960

- ↑ Paul Lévy, Calcul des probabilités, 1925.

- ↑ B.Mandelbrot, Stable Paretian Random Functions and the Multiplicative Variation of Income, Econometrica 1961 http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/1911802.pdf

- ↑ B. Mandelbrot, The variation of certain Speculative Prices, The Journal of Business 1963 [1]

- ↑ Eugene F. Fama, Mandelbrot and the Stable Paretian Hypothesis, The Journal of Business 1963

- ↑ a b Nolan, John P. «Stable Distributions - Models for Heavy Tailed Data». Archivado desde el original el 17 de julio de 2011. Consultado el 21 de febrero de 2009.

- ↑ Voit, Johannes (2005). The Statistical Mechanics of Financial Markets - Springer. Springer. doi:10.1007/b137351.

Enlaces externos

[editar]- The STABLE program for Windows is available from John Nolan's stable webpage: http://academic2.american.edu/~jpnolan/stable/stable.html Archivado el 30 de octubre de 2006 en Wayback Machine.. It calculates the density (pdf), cumulative distribution function (cdf) and quantiles for a general stable distribution, and performs maximum likelihood estimation of stable parameters and some exploratory data analysis techniques for assessing the fit of a data set.

- Matlab codes for simulation of stable variables and estimation of stable parameters are available from RePEc: https://ideas.repec.org/e/pwe42.html#software

![{\displaystyle \exp \!{\Big [}\;it\mu -|c\,t|^{\alpha }\,(1-i\beta \,{\mbox{sgn}}(t)\Phi )\;{\Big ]},}](https://wikimedia.org/eswiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2a65b46daf54e7bbc803ed1ac94cd20a3fb4c788)

![{\displaystyle \varphi (t;\alpha ,\beta ,c,\mu )=\exp \left[~it\mu \!-\!|ct|^{\alpha }\,(1\!-\!i\beta \,{\textrm {sgn}}(t)\Phi )~\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/eswiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e29e93e87fd5d1496831ccfc2ff73ab3175ff8ff)