原子:修订间差异

小无编辑摘要 |

|||

| (未显示58个用户的116个中间版本) | |||

| 第1行: | 第1行: | ||

{{About|物理学中的原子|计算机科学中的原子操作|原子操作|昵称为'''Atom'''的泰国男歌手|查纳坎·拉塔瑙敦|尊稱為原子的人物、孔子的弟子|原宪}} |

|||

{{noteTA |

{{noteTA |

||

|G1=Physics |

|G1=Physics |

||

|1=zh-hans:轨道;zh-hant:軌域; |

|1=zh-hans:轨道; zh-hant:軌域; |

||

|2=zh-hans: |

|2=zh-hans:杂化; zh-hant:混成; |

||

|3=zh- |

|3=zh-hans:能级; zh-hant:能階; |

||

|4=zh-hans:原子序数; zh-hant:原子序; |

|||

|5=zh-cn:电子云; zh-tw:電子雲 |

|||

|6=zh-cn:扫描隧道显微镜; zh-hant:掃描式穿隧電子顯微鏡 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox |

|||

| above = 原子 |

|||

| abovestyle = background-color:#B5B5CC; |

|||

| headerstyle = background-color:#B5B5CC; |

|||

| image = [[Image:Helium atom QM.svg|300px|[[氦]]原子[[基态]]]] |

|||

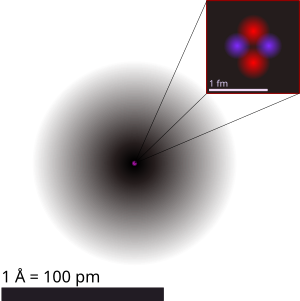

| caption = [[氦]]原子(He)結構示意圖。圖中灰階顯示對應[[电子云]]於[[S軌域|1s原子軌域]]之[[機率密度函數]]的[[积分]]強度。而[[原子核]]僅為示意,紅色為[[質子]]、紫色為[[中子]]。事實上,原子核(與其中之[[核子]]的[[波函数]])也是[[圓對稱#球對稱性|球型對稱]]的(對於更複雜的原子核則非如此)。黑條為1[[埃斯特朗|Å]]({{val|e=-10|u=m}}或100[[皮米|pm]]),小圖白條為1[[飛米|fm]]({{val|e=-15|u=m}}或千份一pm)。 |

|||

| header1 = 分類 |

|||

| data2 = [[化學元素]]可分割的最小單元 |

|||

| header3 = 性質 |

|||

| label4 = [[原子量|质量]] |

|||

| data4 = {{val|1.67|e=-27}}至{{val|4.52|e=-25|u=kg}} |

|||

| label5 = [[電荷]] |

|||

| data5 = 0(電中性,當原子的[[电子]]數與[[質子]]數相等時)或[[离子]]電荷 |

|||

| label6 = [[原子半径|半径]] |

|||

| data6 = 25pm([[氢|H]])至260pm([[铯|Cs]])({{le|元素的原子半徑(數據頁)|Atomic radii of the elements (data page)|數據頁}}) |

|||

| label7 = [[次原子粒子|組分]] |

|||

| data7 = [[电子]]和由質子与中子组成的紧密[[原子核]] |

|||

| label8 = [[可觀測宇宙]]中的原子總數 |

|||

| data8 = ~{{val|e=80}}<ref>{{Cite web|title=Re: How many atoms make up the universe?|url=https://www.madsci.org/posts/archives/oct98/905633072.As.r.html|website={{link-en|MadSci Network}}|date=1998-09-11|language=en|last=Champion|first=Matthew|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000620041650/https://www.madsci.org/posts/archives/oct98/905633072.As.r.html|archive-date=2000-06-20|access-date=2024-07-09}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''原子'''({{lang-en|atom}})是构成[[化學元素]]的{{le|普通物质|Matter#Definition}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.itp.cas.cn/xshd/xshy/201003/W020100319655766305624.pdf|title=“两暗一新”暗物质、暗能量、新理论|author=吴岳良|date=2010-03-18|publisher=中国科学院理论物理研究所|language=zh-hans|accessdate=2022-05-18|quote=可见宇宙有普通物质(ORDINARY MATTER)和普通能量(ORDINARY ENERGY),黑暗宇宙有暗物质(DARK MATTER)和暗能量(DARK ENERGY)|archive-date=2020-05-24|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200524144829/http://www.itp.cas.cn/xshd/xshy/201003/W020100319655766305624.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://dq.yam.com/post/9073|title=「這應該是不可能的」科學家發現不含暗物質的神秘星系|author=時時|date=2018-04-02 |

|||

{| border="1" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="2" style="float:right; margin-left:1em; width:300px;" |

|||

|publisher=地球圖輯隊|language=zh-hant|accessdate=2022-05-18|quote=銀河系的暗物質比肉眼看得到的普通物質(ordinary matter)在整體的質量上多了 30倍。}}</ref>的最小单位<ref>McSween Jr H, Huss G. Cosmochemistry[M]. Cambridge University Press, 2021. p. 419</ref>;原子也是[[化学变化]]中最小的粒子及元素[[化学性质]]的最小單位。 |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="background:gray;"| 氦原子 |

|||

一粒正原子包含有一粒緻密的[[原子核]]及若干圍繞在原子核周圍帶負電的[[电子]]。而反原子的原子核帶負電,周圍的[[反電子]]帶「正電」。正原子的原子核由帶正電的[[質子]]和電中性的[[中子]]組成。反原子的原子核中的[[反質子]]帶負電,從而使反原子的原子核帶負電。當質子數與電子數相同時,這原子就是電中性,称为'''中性原子'''<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://terms.naer.edu.tw/detail/1ae22905038ee57da8b6e89c62ceb484/?seq=1 |title=存档副本 |access-date=2023-08-04 |archive-date=2023-08-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230804013209/https://terms.naer.edu.tw/detail/1ae22905038ee57da8b6e89c62ceb484/?seq=1 |dead-url=no }}</ref>({{lang-en|neutral atom}})<ref>{{cite book |author1=Scientific American |title=Scientific American Science Desk Reference |url=https://archive.org/details/scientificameric00scie_0 |date=1999 |publisher=Wiley |isbn=9780471356752 |page=[https://archive.org/details/scientificameric00scie_0/page/62 62]}}</ref>;否則,就是帶有正電荷或者負電荷的[[离子]]。根據質子和中子數量的不同,原子的類型也不同:質子數決定了該原子屬於哪種元素,而中子數則確定了該原子是此元素的哪種[[同位素]]。 |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"| [[File:Helium atom QM.svg|300px|right|[[氦]]原子基態]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"| <small>氦原子結構示意圖。圖中灰階顯示對應[[電子|電子]][[電子雲|雲]]於1s[[原子軌域]]之[[機率密度函數]]的積分強度。而[[原子核]]僅為示意,[[質子]]以粉紅色、[[中子]]以紫色表示。事實上,原子核(與其中之[[核子]]的[[波函數|波函數]])也是球型對稱的。 (對於更複雜的原子核則非如此)</small> |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="background:gray;"| 分类 |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

{| style="margin:auto;" |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[元素|化学元素]]可分割的最小单元 |

|||

|} |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="background:gray;"| 性质 |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

{| style="margin:auto;" |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[质量]]:|| ≈ 1.67 × 10<sup>-27</sup>至4.52 × 10<sup>-25</sup> kg |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[電荷|电荷]]:|| 0(当原子的电子数与质子数相等时) |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[直徑]]:([[元素的原子半徑(數據頁)|數據頁]]) |

|||

| 50 [[皮米|pm]](H)至520 pm(Cs) |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[可觀測宇宙]]中的原子總數: || ~10<sup>80</sup> <ref>Matthew Champion, [http://www.madsci.org/posts/archives/oct98/905633072. As.r.html "Re: How many atoms make up the universe?"], 1998</ref> |

|||

|} |

|||

|} |

|||

'''原子'''是[[元素]]能保持其化學性質的最小單位。一個正原子包含有一個緻密的[[原子核]]及若干圍繞在原子核周圍帶負電的[[電子]]。而負原子的原子核帶負電,周圍的[[負電子]]帶正電。正原子的原子核由帶正電的[[質子|質子]]和電中性的[[中子]]組成。負原子原子核中的[[反質子]]帶負電,從而使負原子的原子核帶負電。當質子數與電子數相同時,這個原子就是電中性的;否則,就是帶有正電荷或者負電荷的[[離子]]。根據質子和中子數量的不同,原子的類型也不同:質子數決定了該原子屬於哪一種元素,而中子數則確定了該原子是此元素的哪一個[[同位素]]。 |

|||

原子的英 |

原子的英语 atom 是從{{lang-grc|ἄτομος}}(atomos,“不可切分的”)轉化而來。很早以前,[[希腊]]和[[印度]]的[[哲學家]]就提出了原子的不可切分的概念。 17和18世紀時,[[化学家]]發現了物理學的根據:對於某些物質,不能通過化學手段將其繼續的分解。 19世紀晚期和20世紀早期,[[物理学家]]發現了[[次原子粒子|亞原子粒子]]以及原子的內部結構,由此證明原子並不是不能進一步切分。 [[量子力学]]原理能夠為原子提供很好的[[科學模型]]。 <ref>{{Cite web |title=Microcosmos: From Leucippus to Yukawa |url=http://www.columbia.edu/~ah297/unesa/universe/universe-chapter3.html |accessdate=2008-01-17 |last=Haubold |first=Hans |coauthors=Mathai, AM |year=1998 |work=Structure of the Universe |publisher=Common Sense Science |dead-url=yes |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081001172401/http://www.columbia.edu/~ah297/unesa/universe/universe-chapter3.html |archive-date=2008-10-01 }}</ref><ref>Harrison (2003:123–139 ).</ref> |

||

|first=Hans |last=Haubold |coauthors=Mathai, AM |year=1998|url=http://www.columbia.edu/~ah297/unesa/universe/universe-chapter3.html |title=Microcosmos: From Leucippus to Yukawa |work=Structure of the Universe |publisher=Common Sense Science |accessdate=2008-01-17}}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref><ref>Harrison (2003:123–139 ).</ref> |

|||

與日常體驗相比,原子是 |

與日常體驗相比,原子是極小的物體,其質量也很微小,以至於只能以特殊儀器才能觀測到單粒原子,如[[扫描隧道显微镜]]。原子的99.9%的重量集中在[[原子核]],<ref>大部分同位素中核子(原子核内质子与中子之和)比電子多。以氫-1為例,只有一個電子和核子(质子),則質子重量是總質量的<math>\begin{smallmatrix}\frac{1836}{1837} \approx 0.9995\end{smallmatrix}</math>或99.95 %</ref>其中的质子和中子有著相近的質量。幾乎每種元素至少有一種不穩定的同位素,可以[[放射性]][[放射性衰變|衰變]]。這直接導致核轉化,即原子核中的中子數或質子數發生變化。<ref>{{Cite web |title=Radioactive Decays |url=http://www2.slac.stanford.edu/vvc/theory/nuclearstability.html |accessdate=2007-01-02 |author=Staff |date=2007-08-01 |publisher=Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, Stanford University |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090607115741/http://www2.slac.stanford.edu/vvc/theory/nuclearstability.html |archive-date=2009-06-07 }}</ref>原子佔據一組穩定的[[能级]],或稱為[[原子轨道|軌域]]。當它們吸收和放出電子的時候,[[中子|電子]]也可以在不同能級之間跳躍,此時吸收或放出電子的能量與能級之間的能量差相等。此外,電子決定元素的化學特性。 |

||

== 历史 == |

== 历史 == |

||

{{Refimprovesect|time=2015-02-09T00:41:01+00:00}} |

{{Refimprovesect|time=2015-02-09T00:41:01+00:00}} |

||

{{main|原子理論}} |

{{main|原子理論}} |

||

大约在两千五百年前,[[希腊]]哲学家对物质的组成问题争论不休。 |

大约在两千五百年前,[[希腊]]哲学家对物质的组成问题争论不休。'''原子'''派认为物质在无数次分割之后,最终会小到无法分割。原子(atom)一词源自希腊语,意思是“不可分割”。在1803年到1807年之间,英国化学家[[约翰·道尔顿|道尔顿]]发展了这些观点并将它用在它的原子学说中。他相信原子既不能创造也不能消灭。任一[[元素]]所含的原子都一样。{{cn}} |

||

关于[[物质]]是由[[离散量|离散]]单元组成且能 |

关于[[物质]]是由[[离散量|离散]]单元组成且能任意分割的概念流传了几[[千年]],但这些想法只是基于抽象的、[[哲学]]的推理,而非[[实验]]和实证观察。随着[[时间]]的推移以及文化及学派的转变,哲学上原子的性质也有着很大的改变而这种改变往往还带有一些[[精神]]因素。尽管如此,对于原子的基本概念在数千年后仍然有化学家采用,因为它能够很简洁阐述一些化学界的新发现。<ref name="Ponomarev">Ponomarev (1993:14–15).</ref> |

||

===原子論=== |

===原子論=== |

||

[[原子论 (哲学)|原子论]]({{lang-en|atomism}},来自[[古希腊]]语 ἄτομον,atomos,含义为“不可分割”<ref>{{Cite web |title=atom |url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=atom&allowed_in_frame=0 |publisher=[[Online Etymology Dictionary]] |dead-url=no |access-date=2015-02-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150320010327/http://etymonline.com/index.php?term=atom&allowed_in_frame=0 |archive-date=2015-03-20 }}</ref>)是在一些古代传统中发展出的一种自然哲学{{cn}}。原子论者将自然世界理论化为由两基本部分所构成:不可分割的原子和空无的虚空(void){{cn}}。原子论的创始人是[[古希腊人]][[留基伯]],他是[[德谟克利特]]的老师。古代学者在论及原子论时,通常是把他们俩人的学说混在一起的。留基伯的学说由他的学生德谟克利特发展和完善,因此公认[[德谟克利特]]为原子论的主要代表<ref>{{Cite web|title=古希腊原子论的科学意义:由基本的物质微粒解释宏观经验现象|url=http://blog.sciencenet.cn/blog-245-292909.html|publisher=静思--[[中国科学院|中科院]]研究生院教授,博士生导师|dead-url=no|access-date=2010-02-05|archive-date=2021-06-14|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210614021516/http://blog.sciencenet.cn/blog-245-292909.html}}</ref>。 |

|||

原子论的主要内容是:[[宇宙]]的本原是原子和虚空,原子不可构造且永恒不变。原子有两种属性:大小和形状。它们在数量上是无限的。原子按一定的形状、次序和位置,在空无(empty)中通过移动和碰撞,结合和分离,与一粒或以上其他原子相钩结而形成聚簇(cluster)。不同形状、排列和位置的聚簇构成世界上各种宏观物质(substance)。[[德谟克利特]]认为,运用上述原子论的思想,就可以解释世间万物为什么会有重量、形状、尺寸等客观特性;不仅如此,他还认为,另一些特性,比如[[气味]],只有当物体的原子和人[[鼻子|鼻]]互相作用时才显示出来。 |

|||

[[原子论]](英语:Atomism,来自[[古希腊]]语ἄτομον,atomos,含义为“不可分割”<ref>{{cite web|title=atom|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=atom&allowed_in_frame=0|publisher=[[Online Etymology Dictionary]]}}</ref>)是在一些古代传统中发展出的一种自然哲学{{cn}}。原子论者将自然世界理论化为由两基本部分所构成:不可分割的原子和空无的虚空(void){{cn}}。 |

|||

对原子概念的记述可以上溯到[[印度河流域文明|古印度]]和古希腊。有人将印度的耆那教的原子论认定为开创者大雄在[[公元前]]6世纪提出,并将与其同时代的[[彼浮陀伽旃延]]和[[顺世派]]先驱[[阿夷陀翅舍钦婆罗]]的元素思想也称为原子论{{cn}}。正理派和胜论派后来发展出了原子如何组合成更复杂物体的理论{{cn}}。在西方,对原子的记述出现在公元前5世纪[[留基伯]]和[[德谟克利特]]的著作中。对于印度文化影响[[希腊]]还是反之,亦或二者独立演化是有争议{{cn}}。 |

|||

依据[[亚里士多德]]引述,原子是不可构造的和永恒不变的,并且形状和大小有无穷的变化。它们在空无(empty)中移动,相互碰离,有时变成与一个或多个其他原子相钩结而形成聚簇(cluster)。不同形状、排列和位置的聚簇引起世界上各种宏观物质(substance)。{{cn}} |

|||

对原子概念的记述可以上溯到[[古印度]]和古希腊。有人将印度的耆那教的原子论认定为开创者大雄在[[公元前]]6世纪提出,并将与其同时代的彼浮陀伽旃延和顺世派先驱阿夷陀翅舍钦婆罗的元素思想也称为原子论{{cn}}。正理派和胜论派后来发展出了原子如何组合成更复杂物体的理论{{cn}}。在西方,对原子的记述出现在公元前5世纪[[留基伯]]和[[德谟克利特]]的著作中。对于印度文化影响[[希腊]]还是反之,亦或二者独立演化是存在争议的{{cn}}。 |

|||

===科學理論=== |

===科學理論=== |

||

直到[[化学]]作为一门科学开始发展的时候,对原子才有 |

直到[[化学]]作为一门科学开始发展的时候,对原子才有更进一步的理解。1661年,[[自然哲学|自然哲学家]][[罗伯特·波义耳]]出版了《[[怀疑的化学家]]》一书,书中他声称物质是由不同的“微粒”或原子自由组合构成的,而并不是由诸如气、土、火、水等[[四元素说|基本元素]]构成。<ref>Siegfried (2002:42–55).</ref>1789年,既是[[法国]]贵族,又是科学研究者的[[安托万-洛朗·德·拉瓦锡|拉瓦锡]]定义了[[元素]]一词,从此,元素就用来表示化学变化中的最小的单位。<ref>{{Cite web |title=Lavoisier's Elements of Chemistry |url=http://web.lemoyne.edu/~GIUNTA/EA/LAVPREFann.HTML |accessdate=2007-12-18 |work=Elements and Atoms |publisher=Le Moyne College, Department of Chemistry |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070501102647/http://web.lemoyne.edu/~giunta/EA/LAVPREFann.HTML |archive-date=2007-05-01 }}</ref> |

||

1803年[[道尔顿]]创立科学原子论,并在1803年12月与1804年1月在[[英国皇家学会]]作关于原子论的演讲,其中全面阐释了他的原子论思想。其要点为:1.化学元素均由不可再分的微粒组成。这种微粒称为原子。原子在一切化学变化中均保持其不可再分性。2.同一元素的所有原子,在质量和性质上都相同;不同元素的原子,在质量和性质上都不相同。3.不同的元素[[化合]]时,这些元素的原子按简单整数比结合成化合物。尽管从现在的观点来看,道尔顿的观点非常简洁有力(当然存在着错误)但是由于缺乏实验证据和表述不力,这一观点直到20世纪初才獲广泛接受。 |

|||

===现代原子理论=== |

===现代原子理论=== |

||

[[File:A New System of Chemical Philosophy fp.jpg|left|thumb|道尔顿《化学哲学新体系》一书中描述的各种原子和分子。1808年|替代=|429x429像素]] |

|||

[[道耳顿]]的理想没有涉及[[原子]]内部结构。随后,在1897年,第一个亚原子粒子--电子,被发现。1911年,英国物理学家[[欧内斯特·卢瑟福|卢瑟福]]发现每一个原子都含有一个比重很大并且带正电的原子核。1932年中子又被发现。现代化学认为原子由原子核及绕核旋转的电子构成。原子核中含有许多[[质子]]和[[中子]]。质子和中子要比电子重一千八百多倍。质子的带电量是一个单位的正电荷,电子是一个单位的负电荷,中子不带电。 |

|||

[[约翰·道尔顿|道尔顿]]的理想没有涉及'''原子'''内部结构。随后,在1897年,发现了第一粒亚原子粒子──[[电子]]。1911年,新西兰物理学家[[欧内斯特·卢瑟福|卢瑟福]]发现每一粒原子都含有一粒比重很大并且带正电的原子核,他隨後在1919年發現了原子核內部帶正電的質子。1932年英國物理學家[[詹姆斯·查兌克|查德威克]]发现不帶電的中子。现代化学认为原子由原子核及绕核旋转的电子构成。原子核中含有许多[[质子]]和[[中子]]。质子和中子要比电子重約1836倍。质子的带电量是一单位正电荷,电子是一单位负电荷,中子不带电。 |

|||

[[File:A New System of Chemical Philosophy fp.jpg|left|thumb|道尔顿《化学哲学新体系》一书中描述的各种原子和分子。1808年]] |

|||

1803年,英语教师及自然哲学家[[約翰·道爾頓]]用原子的概念解释了为什么不同元素总是呈[[整数]]倍反应,即[[倍比定律]];也解释了为什么某些气体比另外一些更容易溶于水。他提出每一种元素只包含唯一一种原子,而这些原子相互结合起来就形成了[[化合物]]。<ref>Wurtz (1881:1–2).</ref><ref>Dalton (1808).</ref> |

1803年,英语教师及自然哲学家[[約翰·道爾頓]]用原子的概念解释了为什么不同元素总是呈[[整数]]倍反应,即[[倍比定律]];也解释了为什么某些气体比另外一些更容易溶于水。他提出每一种元素只包含唯一一种原子,而这些原子相互结合起来就形成了[[化合物]]。<ref>Wurtz (1881:1–2).</ref><ref>Dalton (1808).</ref> |

||

1827年,英國[[植物学|植物學家]][[罗伯特·布朗|羅伯特·布朗]]在使用[[顯微鏡|显微镜]]观察水面上 |

1827年,英國[[植物学|植物學家]][[罗伯特·布朗|羅伯特·布朗]]在使用[[顯微鏡|显微镜]]观察水面上花粉的时候,发现它们的运动不规则,进一步证明了微粒学说。后来,这现象称为[[布朗运动]]。[[德绍儿克思]]在1877年提出这种现象是由于水分子的热运动而导致的。1905年,[[阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦|爱因斯坦]]提出了第一个数学分析的方法,证明了这猜想。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen |url=http://www.physik.uni-augsburg.de/annalen/history/papers/1905_17_549-560.pdf |last=Einstein |first=Albert |date=1905年5月 |journal=Annalen der Physik |accessdate=2007-02-04 |issue=8 |doi=10.1002/andp.19053220806 |volume=322 |pages=549–560 |language=de |format=PDF |bibcode=1905AnP...322..549E |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20060318060724/http://www.physik.uni-augsburg.de/annalen/history/papers/1905_17_549-560.pdf |archivedate=2006-03-18 |deadurl=yes }}</ref><ref>Mazo (2002:1–7).</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Brownian Motion |url=http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~nd/surprise_95/journal/vol4/ykl/report.html |accessdate=2007-12-18 |last=Lee |first=Y. K. |coauthors=Hoon, Kelvin |year=1995 |publisher=Imperial College, London |dead-url=yes |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071218061408/http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~nd/surprise_95/journal/vol4/ykl/report.html |archive-date=2007-12-18 }}</ref> |

||

在关于[[陰極射線|阴极射线]]的工作中,物理学家[[約瑟夫·汤姆孙]]发现了电子以及它的亚原子特性,粉碎了一直以来认为原子不可再分的设想。<ref name="nobel1096">{{ |

在关于[[陰極射線|阴极射线]]的工作中,物理学家[[约瑟夫·汤姆孙|約瑟夫·汤姆孙]]发现了电子以及它的亚原子特性,粉碎了一直以来认为原子不可再分的设想。<ref name="nobel1096">{{Cite web |title=J.J. Thomson |url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1906/thomson-bio.html |accessdate=2007-12-20 |author=The Nobel Foundation |year=1906 |publisher=Nobelprize.org |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/6GYgrNSic?url=http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1906/thomson-bio.html |archive-date=2013-05-12 }}</ref>汤姆孙认为电子是平均分布在整粒原子上,就如同散布在均匀的正电荷海洋中,它们的负电荷与那些正电荷相互抵消。这也叫做[[梅子布丁模型]]。 |

||

然而,在1909年,在物理学家[[欧内斯特·卢瑟福|卢瑟福]]的指导下,研究者们用氦离子轰击金箔。他们意外的发现有很小一部分离子的偏转角度远远大于使用汤姆孙假设所预测值。卢瑟福根据这 |

然而,在1909年,在物理学家[[欧内斯特·卢瑟福|卢瑟福]]的指导下,研究者们用氦离子轰击金箔。他们意外的发现有很小一部分离子的偏转角度远远大于使用汤姆孙假设所预测值。卢瑟福根据这[[阿尔法粒子散射实验|金箔实验]]的结果提出原子中大部分质量和正电荷都集中在位于原子中心的原子核当中,电子则像行星围绕太阳一样围绕着原子核。带正电的氦离子在穿越原子核附近时,就会大角度被反射。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=The Scattering of α and β Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom |url=http://dbhs.wvusd.k12.ca.us/webdocs/Chem-History/Rutherford-1911/Rutherford-1911.html |last=Rutherford |first=E. |journal=Philosophical Magazine |accessdate=2008-01-18 |year=1911 |volume=21 |pages=669–88 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070205100120/http://dbhs.wvusd.k12.ca.us/webdocs/Chem-History/Rutherford-1911/Rutherford-1911.html |archivedate=2007-02-05 |deadurl=yes }}</ref> |

||

|last=Rutherford |first=E. |

|||

|title=The Scattering of α and β Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom |

|||

|journal=Philosophical Magazine |

|||

|year=1911|volume=21 |pages=669–88 |

|||

|url=http://dbhs.wvusd.k12.ca.us/webdocs/Chem-History/Rutherford-1911/Rutherford-1911.html |

|||

|accessdate=2008-01-18 |

|||

}}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref> |

|||

1913年, |

1913年,[[放射化学|放射化学家]][[弗雷德里克·索迪]]在[[放射性]]衰变产物的实验中发现元素周期表中各位置不只有一种原子。<ref>{{Cite web |title=Frederick Soddy, The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1921 |url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1921/soddy-bio.html |accessdate=2008-01-18 |publisher=Nobel Foundation |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080409210519/http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1921/soddy-bio.html |archive-date=2008-04-09 }}</ref> [[玛格丽特·德·那瓦尔|玛格丽特·陶德]]创造了[[同位素]]一词来表示同一种元素不同种类的原子。在研究离子气体的过程中,汤姆孙发明了一种新技术,可以用来分离不同同位素,最终导致了稳定同位素的发现。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Rays of positive electricity |url=http://web.lemoyne.edu/~giunta/canal.html |last=Thomson |first=Joseph John |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society |accessdate=2007-01-18 |year=1913 |volume=A 89 |pages=1–20 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190308014919/http://web.lemoyne.edu/~giunta/canal.html |archive-date=2019-03-08 |dead-url=no }}</ref> |

||

[[File:Bohr Model.svg|right|thumb|200px|氢原子的[[玻尔模型]],展示了一 |

[[File:Bohr Model.svg|right|thumb|200px|氢原子的[[玻尔模型]],展示了一粒电子在两條固定轨道之间跃迁并释放出一粒特定频率的光子。]] |

||

与此同时,物理学家[[尼尔斯·玻尔|玻尔]]重新审视了卢瑟福的模型,他认为电子应该位于确定的轨道之中,并且能够在不同轨道之间跳跃,而不是像先前认为那样可以自由的向内或向外移动。电子在这些固定轨道间跳跃时,必须吸收或者释放特定的能量。<ref>{{ |

与此同时,物理学家[[尼尔斯·玻尔|玻尔]]重新审视了卢瑟福的模型,他认为电子应该位于确定的轨道之中,并且能够在不同轨道之间跳跃,而不是像先前认为那样可以自由的向内或向外移动。电子在这些固定轨道间跳跃时,必须吸收或者释放特定的能量。<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Atomic Nucleus and Bohr's Early Model of the Atom |url=http://www-spof.gsfc.nasa.gov/stargaze/Q5.htm |accessdate=2007-12-20 |date=2005-05-16 |last=Stern |first=David P. |publisher=NASA Goddard Space Flight Center |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070820084047/http://www-spof.gsfc.nasa.gov/stargaze/Q5.htm |archive-date=2007-08-20 }}</ref>当热源产生的一束[[光]]穿过[[稜鏡|棱镜]]时,能够产生多彩的[[光學頻譜|光谱]]。应用轨道跃迁的理论就能够很好的解释光谱中存在的位置不变的[[譜線|线条]]。<ref>{{Cite web |title=Niels Bohr, The Nobel Prize in Physics 1922, Nobel Lecture |url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1922/bohr-lecture.html |accessdate=2008-02-16 |date=1922-12-11 |last=Bohr |first=Niels |publisher=The Nobel Foundation |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080415183736/http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1922/bohr-lecture.html |archive-date=2008-04-15 }}</ref> |

||

|last=Stern |first=David P. |date=2005-05-16|url=http://www-spof.gsfc.nasa.gov/stargaze/Q5.htm |title=The Atomic Nucleus and Bohr's Early Model of the Atom |publisher=NASA Goddard Space Flight Center |accessdate=2007-12-20 }}</ref>当热源产生的一束[[光]]穿过[[稜鏡|棱镜]]时,能够产生一个多彩的[[光學頻譜|光谱]]。应用轨道跃迁的理论就能够很好的解释光谱中存在的位置不变的[[譜線|线条]]。<ref>{{cite web |last=Bohr |first=Niels |date=1922-12-11|url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1922/bohr-lecture.html |title=Niels Bohr, The Nobel Prize in Physics 1922, Nobel Lecture |publisher=The Nobel Foundation |accessdate=2008-02-16 }}</ref> |

|||

1916年,[[吉爾伯特·路易斯]]发现[[化学键]]的本质就是两粒原子间电子的相互作用。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=The Atom and the Molecule |last=Lewis |first=Gilbert N. |date=1916年4月 |journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society |issue=4 |doi=10.1021/ja02261a002 |volume=38 |pages=762-786}}</ref>众所周之,元素的[[化学性质]]按照[[元素周期表|周期律]]反复的循环。<ref>{{Cite book |title=The Periodic Table |url=https://archive.org/details/periodictableits00scer |last=Scerri |first=Eric R. |publisher=Oxford University Press US |year=2007 |isbn=0195305736 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/periodictableits00scer/page/n227 205]–226}}</ref>1919年,美国化学家[[歐文·朗繆爾]]提出原子中的电子以某种性质相互连接或者说相互聚集。一组电子占有一層特定的[[電子層|电子层]]。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules |url=http://dbhs.wvusd.k12.ca.us/webdocs/Chem-History/Langmuir-1919b.html |last=Langmuir |first=Irving |journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society |accessdate=2008-09-01 |issue=6 |year=1919 |volume=41 |pages=868–934 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20081210082018/http://dbhs.wvusd.k12.ca.us/webdocs/Chem-History/Langmuir-1919b.html |archivedate=2008-12-10 |deadurl=yes }}</ref> |

|||

1916年,[[吉爾伯特·路易斯]]发现[[化学键]]的本质就是两个原子间电子的相互作用。<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|last=Lewis |first=Gilbert N. |

|||

|title=The Atom and the Molecule |

|||

|journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society |

|||

|date=1916年4月|volume=38 |issue=4 |

|||

|pages=762-786 |doi=10.1021/ja02261a002 }}</ref>众所周之,元素的[[化学性质]]按照[[元素周期表|周期律]]反复的循环。<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|first=Eric R. |last=Scerri |year=2007|title=The Periodic Table |pages=205–226 |

|||

|publisher=Oxford University Press US |

|||

|isbn=0195305736 }}</ref>1919年,美国化学家[[歐文·朗繆爾]]提出原子中的电子以某种性质相互连接或者说相互聚集。一组电子占有一个特定的[[電子層|电子层]]。<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|last=Langmuir |first=Irving |

|||

|title=The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules |

|||

|journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society |

|||

|year=1919|volume=41 |issue=6 |pages=868–934 |

|||

|url=http://dbhs.wvusd.k12.ca.us/webdocs/Chem-History/Langmuir-1919b.html |

|||

|accessdate=2008-09-01 }}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref> |

|||

1926年,[[埃尔温·薛定谔|薛定谔]] |

1926年,[[埃尔温·薛定谔|薛定谔]]用[[路易·德布罗意]]于1924年提出的[[波粒二象性]]假说,建立了原子的数学模型,用来将电子描述为三维[[波形]]。使用波形来描述电子的一个直接后果就是在数学上不能够同时得到[[位置向量|位置]]和[[动量]]的精确值,1926年,[[维尔纳·海森堡|海森堡]]建立了相关的方程,这也就是后来著名的[[不确定性原理]]。这概念描述的是,对于测量的某个位置,只能得到一个不确定的动量范围,反之亦然。尽管这模型很难想象,但它能够解释一些以前观测到却不能解释的原子的性质,例如比氢更大的原子的谱线。因此,人们不再使用原子的行星模型,而更倾向于将[[原子轨道]]视为电子存在概率的区域。<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Hydrogen Atom |url=http://www.mathpages.com/home/kmath538/kmath538.htm |accessdate=2007-12-21 |last=Brown |first=Kevin |year=2007 |publisher=MathPages |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080513082947/http://www.mathpages.com/home/kmath538/kmath538.htm |archive-date=2008-05-13 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=The Development of Quantum Mechanics |url=http://www.upscale.utoronto.ca/GeneralInterest/Harrison/DevelQM/DevelQM.html |accessdate=2007-12-21 |date=2000年3月 |last=Harrison |first=David M. |publisher=University of Toronto |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071225095938/http://www.upscale.utoronto.ca/GeneralInterest/Harrison/DevelQM/DevelQM.html |archive-date=2007-12-25 }}</ref> |

||

|last=Brown |first=Kevin |year=2007|url=http://www.mathpages.com/home/kmath538/kmath538.htm |

|||

|title=The Hydrogen Atom |publisher=MathPages |

|||

|accessdate=2007-12-21 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|||

|last=Harrison |first=David M. |date=2000年3月|url=http://www.upscale.utoronto.ca/GeneralInterest/Harrison/DevelQM/DevelQM.html |

|||

|title=The Development of Quantum Mechanics |

|||

|publisher=University of Toronto |

|||

|accessdate=2007-12-21 }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Mass Spectrometer Schematic zh-cn.svg|left|thumb|280px| |

[[File:Mass Spectrometer Schematic zh-cn.svg|left|thumb|280px|质谱仪简易原理图]] |

||

[[质谱]] |

发明[[质谱]]使得科学家可以直接测量原子的准确质量。该设备使用磁体弯曲一束离子,而偏转量取决于原子的质荷比。[[弗朗西斯·阿斯顿]]使用质谱证实了同位素有着不同的质量,并且同位素间的质量差都为整数,称为[[整除规则|整数规则]]。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=The constitution of atmospheric neon |last=Aston |first=Francis W. |journal=[[Philosophical Magazine]] |issue=6 |year=1920 |volume=39 |pages=449–55}}</ref>1932年,[[詹姆斯·查德威克]]发现了中子,解释了这问题。中子是中性的粒子,质量与质子相仿。同位素则重新定义为质子数相同而中子数不同的元素。<ref>{{Cite web |title=Nobel Lecture: The Neutron and Its Properties |url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1935/chadwick-lecture.html |accessdate=2007-12-21 |date=1935-12-12 |last=Chadwick |first=James |publisher=Nobel Foundation |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071012100351/http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1935/chadwick-lecture.html |archive-date=2007-10-12 }}</ref> |

||

|title=The constitution of atmospheric neon |

|||

|journal=[[Philosophical Magazine]] |year=1920|first=Francis W. |last=Aston |

|||

|volume=39 |issue=6 |pages=449–55 }}</ref>1932年,[[詹姆斯·查德威克]]发现了中子,解释了这一个问题。中子是一种中性的粒子,质量与质子相仿。同位素则被重新定义为有着相同质子数与不同中子数的元素。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|last=Chadwick |first=James |date=1935-12-12|url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1935/chadwick-lecture.html |

|||

|title=Nobel Lecture: The Neutron and Its Properties |

|||

|publisher=Nobel Foundation |

|||

|accessdate=2007-12-21 }}</ref> |

|||

1950年代,随着[[粒子加速器]]及[[粒子探测器]]的发展,科学家们可以研究高能粒子间的碰撞。<ref>{{Cite web |title=Accelerators and Nobel Laureates |url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/articles/kullander/ |accessdate=2008-01-31 |date=2001-08-28 |last=Kullander |first=Sven |publisher=The Nobel Foundation |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080413064924/http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/articles/kullander/ |archive-date=2008-04-13 }}</ref>他们发现中子和质子是[[强子]]的一种,由更小的[[夸克]]微粒构成。核物理的[[标准模型理论|标准模型]]也随之发展,能够成功的在亚原子水平解释整粒原子核以及亚原子粒子之间的相互作用。<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Nobel Prize in Physics 1990 |url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1990/press.html |accessdate=2008-01-31 |author=Staff |date=1990-10-17 |publisher=The Nobel Foundation |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080514100040/http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1990/press.html |archive-date=2008-05-14 }}</ref> |

|||

1950年代,随着[[粒子加速器]]及[[粒子探测器]]的发展,科学家们可以研究高能粒子间的碰撞。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|last=Kullander |first=Sven |date=2001-08-28|url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/articles/kullander/ |

|||

|title=Accelerators and Nobel Laureates |

|||

|publisher=The Nobel Foundation |

|||

|accessdate=2008-01-31 }}</ref>他们发现中子和质子是[[强子]]的一种,由更小的[[夸克]]微粒构成。核物理的[[标准模型理论|标准模型]]也随之发展,能够成功的在亚原子水平解释整个原子核以及亚原子粒子之间的相互作用。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|author=Staff |date=1990-10-17|url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1990/press.html |

|||

|title=The Nobel Prize in Physics 1990 |

|||

|publisher=The Nobel Foundation |

|||

|accessdate=2008-01-31 }}</ref> |

|||

1985年左右,[[朱棣文]]及其同事在[[贝尔实验室]]开发了一种新技术,能够使用[[激光]]来冷却原子。[[威廉·丹尼尔·菲利普斯]]团队设法将钠原子置于一个[[磁阱]]中。这两个技术加上由[[克洛德·科昂-唐努德日]]团队基于[[多普勒效应]]开发的一种方法,可以将少量的原子冷却至[[热力学温标|微开尔文]]的温度范围,这样就可以 |

1985年左右,[[朱棣文]]及其同事在[[贝尔实验室]]开发了一种新技术,能够使用[[激光]]来冷却原子。[[威廉·丹尼尔·菲利普斯]]团队设法将钠原子置于一个[[磁阱]]中。这两个技术加上由[[克洛德·科昂-唐努德日]]团队基于[[多普勒效应]]开发的一种方法,可以将少量的原子冷却至[[热力学温标|微开尔文]]的温度范围,这样就可以很高精度研究原子,这也直接导致[[玻色-爱因斯坦凝聚|玻斯-爱因斯坦凝聚]]的发现。<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Nobel Prize in Physics 1997 |url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1997/ |accessdate=2008-02-10 |author=Staff |date=1997-10-15 |publisher=Nobel Foundation |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080409211854/http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1997/ |archive-date=2008-04-09 }}</ref> |

||

|author=Staff |date=1997-10-15|url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1997/ |

|||

|title=The Nobel Prize in Physics 1997 |

|||

|publisher=Nobel Foundation |

|||

|accessdate=2008-02-10 }}</ref> |

|||

历史上认为单一原子过于微小,不能以科学研究。最近,科学家已经成功用单一金属原子与一粒有机[[配體|配体]]连接形成[[单电子晶体管]]。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Coulomb blockade and the Kondo effect in single-atom transistors |author=Park, Jiwoong ''et al'' |url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002Natur.417..722P |journal=Nature |accessdate=2008-01-03 |issue=6890 |doi=10.1038/nature00791 |year=2002 |volume=417 |pages=722–25 |bibcode=2002Natur.417..722P |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080112041123/http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002Natur.417..722P |archive-date=2008-01-12 |dead-url=no }}</ref>一些实验用[[雷射冷卻|激光冷却]]的方法将原子减速并捕获,这些实验能够提升對物质的認知。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Single-atom interference method for generating Fock states |url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1994PhRvA..50.3340D |last=Domokos |first=P. |journal=Physical Review a |accessdate=2008-01-03 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevA.50.3340 |year=1994 |volume=50 |pages=3340–44 |bibcode=1994PhRvA..50.3340D |coauthors=Janszky, J.; Adam, P. |archive-date=2018-10-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181005050018/http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1994PhRvA..50.3340D |dead-url=no }}</ref> |

|||

历史上,因为单个原子过于微小,被认为不能够进行科学研究。最近,科学家已经成功使用一单个金属原子与一个有机[[配體|配体]]连接形成一个[[单电子晶体管]]。<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|author=Park, Jiwoong ''et al'' |journal= Nature |

|||

|year=2002|volume= 417 |issue= 6890 |pages=722–25 |

|||

|title= Coulomb blockade and the Kondo effect in single-atom transistors |

|||

|url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002Natur.417..722P |

|||

|doi=10.1038/nature00791 |accessdate=2008-01-03 |bibcode= 2002Natur.417..722P }}</ref>在一些实验中,通过[[激光冷却]]的方法将原子减速并捕获,这些实验能够带来对于物质更好的理解。<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|first=P. |last=Domokos |coauthors=Janszky, J.; Adam, P. |

|||

|title=Single-atom interference method for generating Fock states |

|||

|journal=Physical Review a |volume=50 |

|||

|pages=3340–44 |year=1994|doi=10.1103/PhysRevA.50.3340 |

|||

|url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1994PhRvA..50.3340D |

|||

|accessdate=2008-01-03 |bibcode= 1994PhRvA..50.3340D }}</ref> |

|||

== 原子的组成 == |

== 原子的组成 == |

||

原子是由带[[正电荷]]的[[原子核]]和带[[负电荷]]的[[电子]]构成。原子'''核'''所带的正'''电荷数'''(即[[核电荷数]])与原子核外电子所带的负电子数相等,故原子呈[[电中性]]。原子可以构成[[分子]],也可以形成[[离子]],也可以直接构成[[物质]]。 |

|||

构成原子的三种粒子(质子、中子、电子)的基本数据: |

|||

{| class=wikitable style="font-size:small;" |

|||

!rowspan="2"|原子的组成 |

|||

!colspan="2"|原子核 |

|||

!rowspan="2"|电子 |

|||

|- |

|||

!质子!!中子 |

|||

|- |

|||

|电性和电量 |

|||

|1粒质子带1单位正电荷 |

|||

|电中性 |

|||

|1粒电子带1单位负电荷 |

|||

|- |

|||

|质量(kg) |

|||

|<math>1.6726\times10^{-27}</math> |

|||

|<math>1.6749\times10^{-27}</math> |

|||

|<math>9.109\times10^{-31}</math> |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[相对原子质量]] |

|||

|1.007 |

|||

|1.008 |

|||

|<math>\frac{1}{1836}</math> |

|||

|} |

|||

=== 亚原子粒子 === |

=== 亚原子粒子 === |

||

{{main|亚原子粒子}} |

{{main|亚原子粒子}} |

||

尽管原子的英文名称(atom)本意是不能 |

尽管原子的英文名称(atom)本意是不能繼續分割的最小粒子,但是在现代科学领域,原子实际上包含了很多不同的亚原子粒子:[[电子]],[[質子|质子]]和[[中子]]。[[氢-1]]原子和带一粒正电荷的[[氢正离子]]例外,前者没有中子,后者沒有电子。 |

||

质子 |

质子有一粒正电荷,质量是电子质量的1836倍,为<math>1.6726 \times 10^{-27}</math>公斤,然而部分质量可以转化为原子[[结合能]]。中子不带电荷,自由中子的质量是电子质量的1839倍,为<math>1.6929 \times 10^{-27}</math>公斤。<ref>Woan (2000:8).</ref>中子和质子的尺寸相仿,均在<math>2.5 \times 10^{-15}</math>m这一数量级,但它们的表面并没能精确定义。<ref>MacGregor (1992:33–37).</ref> |

||

在物理学[[标准模型理论]]中,质子和中子都由名叫[[夸克]]的[[基本粒子]]构成。夸克是[[费米子]]的一种,也是构成物质的两 |

在物理学[[标准模型理论]]中,质子和中子都由名叫[[夸克]]的[[基本粒子]]构成。夸克是[[费米子]]的一种,也是构成物质的两種基本组分之一。另一基本组份称[[輕子|轻子]],电子就是轻子的一种。夸克共有六种,每一种都带有分数的电荷,不是<math display="inline">+\frac{2}{3}</math>就是<math display="inline">-\frac{1}{3}</math>。质子就是由两粒[[上夸克]]和一粒下夸克组成,而中子则是由一粒上夸克和两粒下夸克组成。这区别就解释了为什么中子和质子电荷和质量均有差别。夸克由[[强相互作用]]结合在一起的,由[[膠子|胶子]]作中介。胶子是[[规范玻色子]]的一员,是一种用来传递[[力]]的基本粒子。<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Particle Adventure |url=http://www.particleadventure.org/ |accessdate=2007-01-03 |author=Particle Data Group |year=2002 |publisher=Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070104075936/http://www.particleadventure.org/ |archive-date=2007-01-04 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Elementary Particles |url=http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/ast123/lectures/lec07.html |accessdate=2007-01-03 |date=2006-04-18 |last=Schombert |first=James |publisher=University of Oregon |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/616PzI2QM?url=http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/ast123/lectures/lec07.html |archive-date=2011-08-21 }}</ref> |

||

|author=Particle Data Group |year=2002|url=http://www.particleadventure.org/ |

|||

|title=The Particle Adventure |

|||

|publisher=Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-03 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|||

|first=James |last=Schombert |

|||

|date=2006-04-18|url=http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/ast123/lectures/lec07.html |

|||

|title=Elementary Particles |

|||

|publisher=University of Oregon |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-03 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

=== 原子核 === |

=== 原子核 === |

||

{{main|原子核}} |

{{main|原子核}} |

||

[[File:Binding energy curve - common isotopes.svg|thumb|400px| |

[[File:Binding energy curve - common isotopes.svg|thumb|400px|不同同位素将核子连在一起所需的能量。]] |

||

原子中所有的质子和中子结合起来 |

'''[[原子核]]'''是原子中所有的质子和中子构成的,结合起来很小,它们一起也可以称为[[核子]]。质子带正电荷,中子不显电性,故原子核的正电荷由质子数决定。原子核的半径约等于<math>1.07 \cdot \sqrt[3]{A}</math>[[飛米|fm]]其中<math>A</math>是核子的总数。<ref>Jevremovic (2005:63).</ref>原子半径的数量级大约是10<sup>5</sup>fm,因此原子核半径远远小于原子半径。能在短距离上起作用的[[核力|残留强力]]將核子束缚在一起。当距离小于2.5fm的时候,强力远远大于[[库仑定律|静电力]],因此它能够克服带正电的质子间的相互排斥。<ref name="pfeffer">Pfeffer (2000:330–336).</ref> |

||

同种元素的原子带有相同数量的质子,这 |

同种元素的原子带有相同数量的质子,这数也称[[原子序数]]。而对于某种特定的元素,中子数是可以变化的,这也就决定了该原子是这种元素的哪一种同位素。质子数量和中子数量决定了该原子是这种元素的哪一种[[核素]]。中子数决定了该原子的稳定程度,一些同位素能自发[[放射性]][[衰变模式|衰变]]。<ref>{{Cite web |title=How Does Radioactive Decay Work? |url=http://serc.carleton.edu/quantskills/methods/quantlit/RadDecay.html |accessdate=2008-01-09 |date=2007-10-10 |last=Wenner |first=Jennifer M. |publisher=Carleton College |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080511173156/http://serc.carleton.edu/quantskills/methods/quantlit/RadDecay.html |archive-date=2008-05-11 }}</ref> |

||

|last=Wenner |first=Jennifer M. |date=2007-10-10|url=http://serc.carleton.edu/quantskills/methods/quantlit/RadDecay.html |

|||

|title=How Does Radioactive Decay Work? |

|||

|publisher=Carleton College |accessdate=2008-01-09 }}</ref> |

|||

中子和质子都是[[费米子]]的一种,根据[[量子力学]]中的[[泡利不相容原理]],不可能有完全相同的两 |

中子和质子都是[[费米子]]的一种,根据[[量子力学]]中的[[泡利不相容原理]],不可能有完全相同的两粒费米子同时拥有一样量子物理态。因此,原子核每粒质子都占用不同的能级,中子的情况也与此相同。不过泡利不相容原理并没有禁止质子和中子有相同量子态。<ref name="raymond" /> |

||

[[File:Wpdms physics proton proton chain 1.svg|thumb|265x265px|核聚变示意图,两粒质子聚变生成有一粒质子和一粒中子的氘原子核,并放出[[正電子|正电子]](电子的[[反物质]])以及一粒电子[[中微子]]。|替代=]] |

|||

如果一个原子核的质子数和中子数不相同,那么该原子核很容易发生放射性衰变到一个更低的能级,并且使得质子数和中子数更加相近。因此,质子数和中子数相同或很相近的原子更加不容易衰变。然而,当原子序数逐渐增加时,因为质子之间的排斥力增强,需要更多的中子来使整个原子核变的稳定,所以对上述趋势有所影响。因此,当原子序数大于20时,就不能找到一个质子数与中子数相等而又稳定的原子核了。随着Z的增加,中子和质子的比例逐渐趋于1.5。<ref name="raymond"/> |

|||

如果原子核的质子数和中子数不相同,该原子核很易放射性衰变到更低的能级,拉近质子数和中子数。因此,质子数和中子数相同或很相近的原子更加不易衰变。然而,当原子序数逐渐增加时,质子间排斥力增强,需要更多中子來稳定原子核,所以对上述趋势有所影响。原子序数大于20时,就找不到质子数与中子数相等而又稳定的原子核了。随着Z增加,中子和质子的比例逐渐趋于1.5。<ref name="raymond" /> |

|||

[[File:Wpdms physics proton proton chain 1.svg|right|thumb|200px|核聚变示意图,图中两个质子聚变生成一个包含有一个质子和一个中子的氘原子核,并释放出一个[[正電子|正电子]](电子的[[反物质]])以及一个电子[[中微子]]。]] |

|||

原子核中的质子数和中子数也是可以变化的,不过因为它们之间的力很强,所以需要很高的能量,当多 |

原子核中的质子数和中子数也是可以变化的,不过因为它们之间的力很强,所以需要很高的能量,当多粒粒子聚集形成更重的原子核时,就会发生[[核聚变]],例如两粒核之间的高能碰撞。在太阳的核心,质子需要3-10KeV的能量才能够克服它们之间的相互排斥,也就是[[庫侖障壁|库仑障壁]],进而融合起来形成新的核。<ref>{{Cite web |title=Overcoming the Coulomb Barrier |url=http://burro.cwru.edu/Academics/Astr221/StarPhys/coulomb.html |accessdate=2008-02-13 |date=2002-07-23 |last=Mihos |first=Chris |publisher=Case Western Reserve University |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060912013620/http://burro.cwru.edu/Academics/Astr221/StarPhys/coulomb.html |archive-date=2006-09-12 }}</ref>与此相反的过程是核裂变,在[[核裂变]]中,一个核通常是经过放射性衰变,分裂成为两粒更小的核。使用高能的亚原子粒子或光子轰击也能够改变原子核。如果在过程中,原子核的质子数变了,此原子就变成另一种元素的原子。<ref>{{Cite web |title=ABC's of Nuclear Science |url=http://www.lbl.gov/abc/Basic.html |accessdate=2007-01-03 |author=Staff |date=2007-03-30 |publisher=Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061205215708/http://www.lbl.gov/abc/Basic.html |archive-date=2006-12-05 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Basics of Nuclear Physics and Fission |url=http://www.ieer.org/reports/n-basics.html |accessdate=2007-01-03 |date=2001-03-02 |last=Makhijani |first=Arjun |coauthors=Saleska, Scott |publisher=Institute for Energy and Environmental Research |dead-url=no |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070116045217/http://www.ieer.org/reports/n-basics.html |archive-date=2007-01-16 }}</ref> |

||

|last=Mihos |first=Chris |date=2002-07-23|url=http://burro.cwru.edu/Academics/Astr221/StarPhys/coulomb.html |

|||

|title=Overcoming the Coulomb Barrier |

|||

|publisher=Case Western Reserve University |

|||

|accessdate=2008-02-13 }}</ref>与此相反的过程是核裂变,在[[核裂变]]中,一个核通常是经过放射性衰变,分裂成为两个更小的核。使用高能的亚原子粒子或光子轰击也能够改变原子核。如果在一个过程中,原子核中质子数发生了变化,则此原子就变成了另外一种元素的原子了。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|author=Staff |date=2007-03-30|url=http://www.lbl.gov/abc/Basic.html |

|||

|title=ABC's of Nuclear Science |

|||

|publisher=Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-03 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|||

|first=Arjun |last=Makhijani |coauthors=Saleska, Scott |

|||

|date=2001-03-02|url=http://www.ieer.org/reports/n-basics.html |

|||

|title=Basics of Nuclear Physics and Fission |

|||

|publisher=Institute for Energy and Environmental Research |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-03 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

如果核聚变后产生的原子核质量小于聚变前原子质量的总和,那么根据爱因斯坦的[[質能方程|质能方程]], |

如果核聚变后产生的原子核质量小于聚变前原子质量的总和,那么根据爱因斯坦的[[質能方程|质能方程]],质量的差就以能量形式释放出來。这差别实际是原子核之间的[[结合能]]。<ref>Shultis ''et al'' (2002:72–6).</ref> |

||

对于两 |

对于两粒原子序数在[[铁]]或[[镍]]之前的原子核来说,它们之间的核聚变是[[放热过程]],也就是说过程释放的能量大于将它们连在一起的能量。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=The atomic nuclide with the highest mean binding energy |url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995AmJPh..63..653F |last=Fewell |first=M. P. |journal=[[American Journal of Physics]] |accessdate=2007-02-01 |issue=7 |doi=10.1119/1.17828 |year=1995 |volume=63 |pages=653–58 |bibcode=1995AmJPh..63..653F |archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/5xNHry2gq?url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995AmJPh..63..653F |archive-date=2011-03-22 |dead-url=no }}</ref>正是因为如此,才确保了恒星中的核聚变能够自我维持。对于更重一些的原子来说,结合能开始减少,也就是说它们的核聚变会是[[吸热过程]]。因此,这些更重的原子不能以核聚变产能,也就不能够维持恒星的[[流体静力平衡]]。<ref name="raymond">{{cite web |

||

|last= |

|last=Raymond |

||

|first=David |

|||

|title=The atomic nuclide with the highest mean binding energy |

|||

|date=2006-04-07 |

|||

|journal=[[American Journal of Physics]] |

|||

|url=http://physics.nmt.edu/~raymond/classes/ph13xbook/node216.html |

|||

|year=1995|volume=63 |issue=7 |pages=653–58 |

|||

|title=Nuclear Binding Energies |

|||

|url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995AmJPh..63..653F |

|||

|publisher=New Mexico Tech |

|||

|accessdate= 2007-02-01 |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-03 |

|||

|doi=10.1119/1.17828 |bibcode= 1995AmJPh..63..653F }}</ref>正是因为如此,才确保了恒星中的核聚变能够自我维持。对于更重一些的原子来说,结合能开始减少,也就是说它们的核聚变会是一个[[吸热过程]]。因此,这些更重的原子不能够进行产能的核聚变,也就不能够维持恒星的[[流体静力平衡]]。<ref name="raymond">{{cite web |

|||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|last=Raymond |first=David |date=2006-04-07|url=http://physics.nmt.edu/~raymond/classes/ph13xbook/node216.html |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20021201030437/http://physics.nmt.edu/~raymond/classes/ph13xbook/node216.html |

|||

|title=Nuclear Binding Energies |

|||

|archivedate=2002-12-01 |

|||

|publisher=New Mexico Tech |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-03 }}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref> |

|||

=== 电子云 === |

=== 电子云 === |

||

{{main|电子云|原子轨道}} |

{{main|电子云|原子轨道}} |

||

[[File:Potential energy well.svg |

[[File:Potential energy well.svg|thumb|势阱显示了要到每一个位置''x''所需要的最低能量<math>V(x)</math>。如果粒子的能量为<math>E</math>,它就限制在<math>x_1</math>和<math>x_2</math>间。|替代=]] |

||

在 |

在原子中,电子和质子以[[電磁力|电磁力]]相互吸引,也正是这道力将电子束缚在环绕着原子核的[[靜電學|静电]][[球對稱位勢|位势阱]]中,要从这[[势阱]]中逃逸则需要外部能量。电子离原子核越近,吸引力则越大。因此,与外层电子相比,离核近的电子需要更多能量才能够逃逸。<ref name="歐風烈2018">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-bR9DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA407 |title=陽陰宇宙: 重新思考我們對宇宙的想法 |last=歐風烈 |date=1 December 2018 |publisher=Fong Lieh Ou(Showwe Information Co Ltd) |isbn=978-957-43-6142-7 |pages=407– |access-date=2019-04-11 |archive-date=2022-04-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220404040823/https://books.google.com/books?id=-bR9DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA407 |dead-url=no }}</ref> |

||

[[原子轨道]]则是 |

[[原子轨道]]则是描述电子在核内的概率分布的数学方程。在实际中,只有一组离散的(或量子化的)轨道存在,其他可能的形式会很快的坍塌成更稳定的形式。<ref name=Brucat>{{cite web |

||

|last=Brucat |first=Philip J. |year=2008|url=http://www.chem.ufl.edu/~itl/2045/lectures/lec_10.html |

|last=Brucat |

||

|first=Philip J. |

|||

|year=2008 |

|||

|url=http://www.chem.ufl.edu/~itl/2045/lectures/lec_10.html |

|||

|title=The Quantum Atom |publisher=University of Florida |

|title=The Quantum Atom |

||

|publisher=University of Florida |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-04 |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-04 }}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref>这些轨道可以有一个或多个的环或节点,并且它们的大小,形状和空间方向都有不同。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|last=Manthey |first=David |year=2001|url=http://www.orbitals.com/orb/ |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20061207032136/http://www.chem.ufl.edu/~itl/2045/lectures/lec_10.html |

|||

|title=Atomic Orbitals |publisher=Orbital Central |

|||

|archivedate=2006-12-07 |

|||

|accessdate=2008-01-21 }}</ref> |

|||

}}</ref>这些轨道可以有一个或以上的环或节点,并且它们的大小,形状和空间方向都有不同。<ref>{{cite web |last=Manthey |first=David |year=2001 |url=http://www.orbitals.com/orb/ |title=Atomic Orbitals |publisher=Orbital Central |accessdate=2008-01-21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080110102801/http://www.orbitals.com/orb/ |archive-date=2008-01-10 |dead-url=no }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:S-p-Orbitals.svg|left|250px|thumb|前五 |

[[File:S-p-Orbitals.svg|left|250px|thumb|前五條原子轨道的波函数。三條[[P軌域|2p轨道]]中的每條都有一粒角节点,因此有特定的朝向。它们都有一个最小值点在中心。]] |

||

每 |

每條原子轨道都对应一粒电子的[[能级]]。电子可以吸收一粒有足够能量的光子而跃迁到更高的能级。同样,通过[[自发辐射]],在高能级态的电子也可以跃迁回低能级态,放出光子。这些典型的能量,也就是不同量子态之间的能量差,可以用来解释原子[[譜線|谱线]]。<ref name=Brucat/> |

||

在原子核中除去或增加一 |

在原子核中除去或增加一粒电子所需要的能量远远小于核子的结合能,这些能量称为[[电子亲合能|电子结合能]]。例如:夺去氢原子中[[基态]]电子只需要13.6eV。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Herter |first=Terry |year=2006|url=http://instruct1.cit.cornell.edu/courses/astro101/lectures/lec08.htm |

|last=Herter |

||

|first=Terry |

|||

|year=2006 |

|||

|url=http://instruct1.cit.cornell.edu/courses/astro101/lectures/lec08.htm |

|||

|title=Lecture 8: The Hydrogen Atom |

|title=Lecture 8: The Hydrogen Atom |

||

|publisher=Cornell University |

|||

|publisher=Cornell University |accessdate=2008-02-14 }}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref>当电子数与质子数相等时,原子是[[电中性]]的。如果电子数大于或小于质子数时,该原子就会被称为[[离子]]。原子最外层电子可以移动至相邻的原子,也可以由两个原子所共有。正是由于有了这种机理,原子才能够键合形成[[分子]]或其他种类的[[化合物]],例如离子或共价的网状[[晶体]]。<ref>Smirnov (2003:249–72).</ref> |

|||

|accessdate=2008-02-14 |

|||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080415114913/http://instruct1.cit.cornell.edu/Courses/astro101/lectures/lec08.htm |

|||

|archivedate=2008-04-15 |

|||

}}</ref>当电子数与质子数相等时,原子是[[电中性]]的。如果电子数大于或小于质子数时,该原子就会称为[[离子]]。原子最外层电子可以移动至相邻的原子,也可以由两粒原子所共有。正是由于有了这种机理,原子才能够键合形成[[分子]]或其他种类的[[化合物]],例如离子或共价的网状[[晶体]]。<ref>Smirnov (2003:249–72).</ref> |

|||

== 性质 == |

== 性质 == |

||

| 第251行: | 第196行: | ||

{{main|同位素}} |

{{main|同位素}} |

||

根据定义, |

根据定义,有相同质子数的原子即属同一元素,质子数相同而中子数不同的则是同一元素的不同同位素。例如,所有的氢原子都只有一粒质子,但氢原子的同位素有几种,分别含有零粒中子(氢-1,目前最常见的类型,有时也称为[[氫原子|氕]]),一粒中子([[氘]]),两粒中子([[氚]])以及[[氫的同位素|更多中子]]。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Matis |

|last=Matis |

||

|first=Howard S. |

|||

|date=2000-08-09 |

|||

|url=http://www.lbl.gov/abc/wallchart/chapters/02/3.html |

|||

|title=The Isotopes of Hydrogen |

|title=The Isotopes of Hydrogen |

||

|work=Guide to the Nuclear Wall Chart |

|work=Guide to the Nuclear Wall Chart |

||

|publisher=Lawrence Berkeley National Lab |

|publisher=Lawrence Berkeley National Lab |

||

|accessdate=2007-12-21 |

|accessdate=2007-12-21 |

||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071218153548/http://www.lbl.gov/abc/wallchart/chapters/02/3.html |

|||

|last=Weiss |first=Rick |date=2006-10-17|title=Scientists Announce Creation of Atomic Element, the Heaviest Yet |

|||

|archive-date=2007-12-18 |

|||

|publisher=Washington Post |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/10/16/AR2006101601083.html |

|||

}}</ref>原子序数从1(氢)到118([[Og]])均为已知元素。<ref>{{cite news |last=Weiss |first=Rick |date=2006-10-17 |title=Scientists Announce Creation of Atomic Element, the Heaviest Yet |publisher=Washington Post |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/10/16/AR2006101601083.html |accessdate=2007-12-21 |archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/616Q0bWla?url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/10/16/AR2006101601083.html |archive-date=2011-08-21 |dead-url=no }}</ref>对于所有[[原子序]]数大于[[82]]的同位素都有放射性。<ref name="sills">Sills (2003:131–134).</ref><ref name=dume>{{cite news |last=Dumé |first=Belle |date=2003-04-23 |title=Bismuth breaks half-life record for alpha decay |publisher=Physics World |url=http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/17319 |accessdate=2007-12-21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071214151450/http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/17319 |archive-date=2007-12-14 |dead-url=no }}</ref> |

|||

|accessdate=2007-12-21 }}</ref>对于所有[[原子序]]数大于[[82]]的同位素都有放射性。<ref name=sills>Sills (2003:131–134).</ref><ref name=dume>{{cite news |

|||

|last=Dumé |first=Belle |date=2003-04-23|title=Bismuth breaks half-life record for alpha decay |

|||

|publisher=Physics World |

|||

|url=http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/17319 |

|||

|accessdate=2007-12-21 }}</ref> |

|||

地球上自然存在约[[339]]种[[核素]],其中[[255]]种是稳定的,约占总数79%。<ref>{{cite web |last=Lindsay |first=Don |date=2000-07-30 |url=http://www.don-lindsay-archive.org/creation/isotope_list.html |title=Radioactives Missing From The Earth |publisher=Don Lindsay Archive |accessdate=2007-05-23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070428225550/http://www.don-lindsay-archive.org/creation/isotope_list.html |archive-date=2007-04-28 |dead-url=no }}</ref>80种元素有一種或以上的[[稳定同位素]]。[[锝|第43号元素]]、[[钷|第61号元素]]及所有原子序数大于等于[[铋|83]]的元素没有稳定的同位素。有十六种元素只含有一个稳定的同位素,而拥有同位素最多的元素,[[锡]],则有十个同位素。<ref name="CRC">CRC Handbook (2002).</ref> |

|||

地球上自然存在约[[339]]种核素,其中[[255]]种是稳定的,约占总数79%。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|last=Lindsay |first=Don |date=2000-07-30|url=http://www.don-lindsay-archive.org/creation/isotope_list.html |

|||

|title=Radioactives Missing From The Earth |

|||

|publisher=Don Lindsay Archive |

|||

|accessdate=2007-05-23 }}</ref>80种元素含有一个或一个以上的[[稳定同位素]]。[[锝|第43号元素]]、[[钷|第61号元素]]及所有原子序数大于等于[[铋|83]]的元素没有稳定的同位素。有十六种元素只含有一个稳定的同位素,而拥有同位素最多的元素,[[锡]],则有十个同位素。<ref name=CRC>CRC Handbook (2002).</ref> |

|||

同位素的稳定性不只受到质子数与中子数之比的影响,也受到所谓幻数的影响,实际上幻数就代表了全满的量子层。这些量子层对应于原子核层模型中一组能级。在已知的269种稳定核素中,只有四 |

同位素的稳定性不只受到质子数与中子数之比的影响,也受到所谓幻数的影响,实际上幻数就代表了全满的量子层。这些量子层对应于原子核层模型中一组能级。在已知的269种稳定核素中,只有四種同时有奇数粒质子和奇数粒中子。它们是[[氢|<sup>2</sup>H]], [[锂|<sup>6</sup>Li]], [[硼|<sup>10</sup>B]]和[[氮|<sup>14</sup>N]];对于放射性核素来说,也只有5种奇-奇核素的[[半衰期]]超过一亿年:[[钾|<sup>40</sup>K]], [[钒|<sup>50</sup>V]], [[镧|<sup>138</sup>La]],[[镥|<sup>176</sup>Lu]]和[[钽|<sup>180m</sup>Ta]]。这是因为对于大多数奇-奇核素来说,很易会[[β衰变]],产生更稳定的偶-偶核素。<ref name=CRC/> |

||

=== 质量 === |

=== 质量 === |

||

{{main|原子质量}} |

{{main|原子质量}} |

||

因为原子质量的绝大部分是质子和中子的质量,所以质子和中子数量的总和叫做[[質量數|质量数]]。原子的静止质量通常用[[原子质量单位|统一原子质量单位]](u)来表示,也 |

因为原子质量的绝大部分是质子和中子的质量,所以质子和中子数量的总和叫做[[質量數|质量数]]。原子的静止质量通常用[[原子质量单位|统一原子质量单位]](u)来表示,也称作道尔顿(Da)。这单位定义为电中性的[[碳-12|碳12]]质量的十二分之一,约为<math>1.660\ 556\ 5 \times 10^{-27}</math>公斤。<ref name=iupac/>氢最轻的同位素氕是最轻的原子,重约1.007825u。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Chieh |

|last=Chieh |

||

|first=Chung |

|||

|date=2001-01-22|url=http://www.science.uwaterloo.ca/~cchieh/cact/nuctek/nuclideunstable.html |

|date=2001-01-22 |

||

|url=http://www.science.uwaterloo.ca/~cchieh/cact/nuctek/nuclideunstable.html |

|||

|title=Nuclide Stability |

|title=Nuclide Stability |

||

|publisher=University of Waterloo |

|publisher=University of Waterloo |

||

|accessdate=2007-01-04 |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-04 }}</ref>一个原子的质量约是质量数与原子质量单位的乘积。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070830110015/http://www.science.uwaterloo.ca/~cchieh/cact/nuctek/nuclideunstable.html |

|||

|archive-date=2007-08-30 |

|||

|dead-url=yes |

|||

}}</ref>原子质量约是质量数与原子质量单位的乘积。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ele=&ascii=html&isotype=some |

|url=http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ele=&ascii=html&isotype=some |

||

|title=Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for All Elements |

|title=Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for All Elements |

||

|publisher=National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|publisher=National Institute of Standards and Technology |

||

|accessdate=2007-01-04 |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-04 }}</ref>最重的稳定原子是铅-208,<ref name=sills/>质量为207.9766521u。<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061231212733/http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ele=&ascii=html&isotype=some |

|||

|last=Audi |first=G. |coauthors=Wapstra, A. H.; Thibault C. |

|||

|archive-date=2006-12-31 |

|||

|title=The Ame2003 atomic mass evaluation(II) |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

|journal=Nuclear Physics |

|||

}}</ref>最重的稳定原子是铅-208,<ref name=sills/>质量为207.9766521u。<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|year=2003|volume=A729 |pages=337–676 |

|||

|last=Audi |

|||

|url=http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/amdc/web/masseval.html |

|||

|first=G. |

|||

|accessdate=2008-02-07 }}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref> |

|||

|coauthors=Wapstra, A. H.; Thibault C. |

|||

就算是最重的原子,化学家也很难直接对其进行操作,所以它们通常使用另外一个单位,[[摩尔]]。摩尔的定义是对于任意一种元素,一摩尔总是含有同样数量的原子,约为6.022×10<sup>23</sup>。因此,如果一个元素的原子质量为1u,一摩尔该原子的质量就为0.001kg,也就是1克。例如,碳的原子质量是12u,一摩尔碳的质量则是0.012kg。<ref name=iupac>Mills ''et al'' (1993).</ref> |

|||

|title=The Ame2003 atomic mass evaluation(II) |

|||

|journal=Nuclear Physics |

|||

|year=2003 |

|||

|volume=A729 |

|||

|pages=337–676 |

|||

|url=http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/amdc/web/masseval.html |

|||

|accessdate=2008-02-07 |

|||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080916155656/http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/amdc/web/masseval.html |

|||

|archivedate=2008-09-16 |

|||

}}</ref>就算是最重的原子,化学家也很难直接操作之,所以它们通常使用另一单位,[[摩尔 (单位)|摩尔]],簡稱摩。摩的定义是对于任何元素,一摩总是有同样数量的原子,约<math>6.022 \times 10^{23}</math>。如果元素的原子质量为1u,一摩该原子的质量就为0.001kg,也就是1克。例如,碳的原子质量是12u,一摩碳的质量则是0.012kg。<ref name="iupac">Mills ''et al'' (1993).</ref> |

|||

=== 大小 === |

=== 大小 === |

||

{{main|原子半径}} |

{{main|原子半径}} |

||

原子并没有 |

原子并没有精确定义的最外层,只有当两粒原子形成[[化学键]]后,测量两粒原子核间的距离,才能得到原子半径的近似值。影响原子半径的因素很多,包括在[[元素周期表]]的位置,化学键的类型,周围的原子数(配位数)以及[[自旋]]。<ref>{{cite journal |

||

|last |

|last = Shannon |

||

|title=Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides |

|first = R. D. |

||

|title = Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides |

|||

|journal=[[Acta Crystallographica]], Section a |

|journal = [[Acta Crystallographica]], Section a |

||

|year |

|year = 1976 |

||

|volume = 32 |

|||

|url=http://journals.iucr.org/a/issues/1976/05/00/issconts.html |

|||

|pages = 751 |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-03 |

|||

|url = http://journals.iucr.org/a/issues/1976/05/00/issconts.html |

|||

|doi=10.1107/S0567739476001551 |bibcode= 1976AcCrA..32..751S }}</ref>在元素周期表中,原子的半径变化的大体趋势是自上而下增加,而从左至右减少。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|accessdate = 2007-01-03 |

|||

|last=Dong |first=Judy |year=1998|url=http://hypertextbook.com/facts/MichaelPhillip.shtml |

|||

|doi = 10.1107/S0567739476001551 |

|||

|title=Diameter of an Atom |

|||

|bibcode = 1976AcCrA..32..751S |

|||

|publisher=The Physics Factbook |

|||

|author = |

|||

|accessdate=2007-11-19 }}</ref>因此,最小的原子是[[氦]],半径为32pm;最大的原子是[[铯]],半径为225pm。<ref>Zumdahl (2002).</ref>因为这样的尺寸远远小于可见光的波长(约400-700nm),所以不能够通过[[光学显微镜]]来观测它们。然而,使用[[扫描隧道显微镜]]我们能够观察到单个原子。 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070930224738/http://journals.iucr.org/a/issues/1976/05/00/issconts.html |

|||

|archive-date = 2007-09-30 |

|||

|dead-url = no |

|||

}}</ref>在元素周期表中,原子的半径变化的大体趋势是自上而下增加,而从左至右减少。<ref>{{cite web |last=Dong |first=Judy |year=1998 |url=http://hypertextbook.com/facts/MichaelPhillip.shtml |title=Diameter of an Atom |publisher=The Physics Factbook |accessdate=2007-11-19 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071104160920/http://hypertextbook.com/facts/MichaelPhillip.shtml |archive-date=2007-11-04 |dead-url=no }}</ref>因此,最小的原子是[[氦]],半径32pm;最大的原子是[[铯]],半径为225pm。<ref>Zumdahl (2002).</ref>因为这样的尺寸远远小于可见光的波长(约400-700nm),所以不能够通过[[光学显微镜]]来观测它们。然而,使用[[扫描隧道显微镜]]我们能够观察到单粒原子。 |

|||

可以看到:原子的体积很小。一根人的[[頭髮|头发]]的直径大约是一百万 |

可以看到:原子的体积很小。一根人的[[頭髮|头发]]的直径大约是一百万粒原子。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|author=Staff |year=2007|url=http://oregonstate.edu/terra/2007winter/features/nanotech.php |

|author=Staff |

||

|year=2007 |

|||

|url=http://oregonstate.edu/terra/2007winter/features/nanotech.php |

|||

|title=Small Miracles: Harnessing nanotechnology |

|title=Small Miracles: Harnessing nanotechnology |

||

|publisher=Oregon State University |

|publisher=Oregon State University |

||

|accessdate=2007-01-07 |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-07 }}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}—describes the width of a human hair as 10<sup>5</sup> nm and 10 carbon atoms as spanning 1 nm.</ref>一滴水则大约有二十[[中文数字|米]](2×10<sup>21</sup>)个氧原子以及两倍的氢原子。<ref>Padilla ''et al''(2002:32)—"There are 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (that's 2 sextillion) atoms of oxygen in one drop of water—and twice as many atoms of hydrogen."</ref>一[[克拉]][[钻石]]重量为2×10<sup>-4</sup>kg,含有约100垓个碳原子。<ref>A carat is 200 milligrams. [[Atomic mass|By definition]], Carbon-12 has 0.012 kg per mole. The [[Avogadro constant]] defines 6{{Esp|23}} atoms per mole.</ref>如果[[苹果]]被放大到[[地球]]的大小,那么苹果中的原子大约就有原来苹果那么大了。<ref>Feynman (1995).</ref> |

|||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071204164837/http://oregonstate.edu/terra/2007winter/features/nanotech.php |

|||

|archivedate=2007-12-04 |

|||

}}—describes the width of a human hair as 10<sup>5</sup> nm and 10 carbon atoms as spanning 1 nm.</ref>一滴水则大约有二十[[中文数字|垓]](<chem>2 \times 10^{21}</chem>)粒氧原子以及两倍的氢原子。<ref>Padilla ''et al''(2002:32)—"There are 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (that's 2 sextillion) atoms of oxygen in one drop of water—and twice as many atoms of hydrogen."</ref>一[[克拉]][[钻石]]重量为<math>2 \times 10^{-4}</math>kg,含有约100垓粒碳原子。<ref>A carat is 200 milligrams. [[Atomic mass|By definition]], Carbon-12 has 0.012 kg per mole. The [[Avogadro constant]] defines 6{{Esp|23}} atoms per mole.</ref>如果[[苹果]]放大到[[地球]]的大小,苹果中的原子就大约有原来苹果那么大。<ref>Feynman (1995).</ref> |

|||

=== 放射性 === |

=== 放射性 === |

||

{{main|放射性}} |

{{main|放射性}} |

||

[[File:Isotopes and half-life.svg|right|280px|thumb|这个图表展示了含有Z |

[[File:Isotopes and half-life.svg|right|280px|thumb|这个图表展示了含有Z粒质子和N粒中子的同位素的半衰期(T<sub>½</sub>),单位是秒]] |

||

每 |

每种元素都有一个或以上同位素有不稳定的原子核,从而能放射性衰变,在这个过程中,原子核可释放出粒子或电磁辐射。原子核半径大于强力的作用半径时就可能會放射性衰变,而强力的作用半径仅为几飞米。<ref name=splung>{{cite web |

||

|url=http://www.splung.com/content/sid/5/page/radioactivity |

|url=http://www.splung.com/content/sid/5/page/radioactivity |

||

|title=Radioactivity |

|title=Radioactivity |

||

|publisher=Splung.com |

|||

|accessdate=2007-12-19 |

|accessdate=2007-12-19 |

||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071204135150/http://www.splung.com/content/sid/5/page/radioactivity |

|||

|archive-date=2007-12-04 |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

最常见的放射性衰变如下:<ref>L'Annunziata (2003:3–56).</ref><ref>{{cite web |

最常见的放射性衰变如下:<ref>L'Annunziata (2003:3–56).</ref><ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Firestone |first=Richard B. |date=2000-05-22|url=http://isotopes.lbl.gov/education/decmode.html |

|last=Firestone |

||

|first=Richard B. |

|||

|date=2000-05-22 |

|||

|url=http://isotopes.lbl.gov/education/decmode.html |

|||

|title=Radioactive Decay Modes |

|title=Radioactive Decay Modes |

||

|publisher=Berkeley Laboratory |

|publisher=Berkeley Laboratory |

||

|accessdate=2007-01-07 |

|accessdate=2007-01-07 |

||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20060929111801/http://isotopes.lbl.gov/education/decmode.html |

|||

|archivedate=2006-09-29 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

* [[α衰变]]:原子核释放一 |

* [[α衰变]]:原子核释放一粒α粒子,即含有两粒质子和两粒中子的氦原子核。衰变产生[[原子序数]]低一些的新元素。 |

||

* [[β衰变]]:弱相互作用的现象,过程中 |

* [[β衰变]]:弱相互作用的现象,过程中中子转变成质子或者质子转变成中子。前者亦释放一粒电子和一粒反中微子,后者则释放一粒正电子和一粒中微子。所释放的电子或正电子叫β粒子。因此,β衰变能够使得该原子的原子序数增加或减少一。 |

||

* [[γ衰变]]:原子核的能级降低,释放出电磁波辐射,通常在释放了α粒子或β粒子后发生。 |

* [[γ衰变]]:原子核的能级降低,释放出电磁波辐射,通常在释放了α粒子或β粒子后发生。 |

||

其它比较罕见的放射性衰变还包括:释放中子或质子,释放[[核子]]团或电子团,通过[[内转换]]产生高速的电子而非[[β粒子|β射线]]以及高能的光子而非伽马射线。 |

其它比较罕见的放射性衰变还包括:释放中子或质子,释放[[核子]]团或电子团,通过[[内转换]]产生高速的电子而非[[β粒子|β射线]]以及高能的光子而非伽马射线。 |

||

每一个放射性同位素都有一个特征衰变期间,即半衰期。[[半衰期]]就是一半样品发生衰变所需要的时间。这是一种[[指数衰 |

每一个放射性同位素都有一个特征衰变期间,即半衰期。[[半衰期]]就是一半样品发生衰变所需要的时间。这是一种[[指数衰减]],即样品在每一个半衰期内恒定的衰变50%,换句话说,当两次半衰期之后,就只剩下25%的起始同位素了。<ref name=splung/> |

||

=== 磁矩 === |

=== 磁矩 === |

||

{{main|电磁偶极矩|核磁矩}} |

{{main|电磁偶极矩|核磁矩}} |

||

基本微粒都有一个固有性质,就像在宏观物理中围绕[[质心]]旋转的物体都有[[角动量]]一样,在[[量子力学]] |

基本微粒都有一个固有性质,就像在宏观物理中围绕[[质心]]旋转的物体都有[[角动量]]一样,在[[量子力学]]叫[[自旋]]。但是严格来说,这些微粒仅仅是一些点,不能够旋转。自旋的单位是[[普朗克常数|约化普朗克常数]](<math>\hbar</math>),电子、质子和中子的自旋都是½<math>\hbar</math>。在原子里,电子围绕原子核运动,所以除了自旋,它们还有[[軌角動量|轨道角动量]]。而对于原子核来说,轨道角动量是起源于自身的自旋。<ref>{{Cite web |title=Chapter 3: Spin Physics |url=http://astro.rit.edu/htbooks/nmr/bnmr.htm |accessdate=2007-01-07 |last=Hornak |first=J. P. |year=2006 |work=The Basics of NMR |publisher=Rochester Institute of Technology |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070526190509/http://astro.rit.edu/htbooks/nmr/bnmr.htm |archivedate=2007-05-26 |deadurl=yes }}</ref> |

||

|last=Hornak |first=J. P. |year=2006|url=http://astro.rit.edu/htbooks/nmr/bnmr.htm |

|||

|title=Chapter 3: Spin Physics |work=The Basics of NMR |

|||

|publisher=Rochester Institute of Technology |

|||

|accessdate=2007-01-07 }}</ref> |

|||

正如 |

正如旋转的带电物体能够产生[[磁場|磁场]]一样,原子所产生的磁场,即它的[[磁矩]],就是由这些不同的角动量决定的。然后,自旋对它的影响应该是最大的。因为电子的一个性质就是要符合[[泡利不相容原理]],即不能有两粒位于同样量子态的电子,所以当电子成对时,总是一个自旋朝上而另外一个自旋朝下。这样,它们产生的磁场相互抵消。对于某些带有偶数电子的原子,总的磁偶极矩会减少至零。<ref name=schroeder>{{cite web |

||

|last=Schroeder |first=Paul A. |

|last=Schroeder |

||

|first=Paul A. |

|||

|date=2000-02-25|url=http://www.gly.uga.edu/schroeder/geol3010/magnetics.html |

|date=2000-02-25 |

||

|url=http://www.gly.uga.edu/schroeder/geol3010/magnetics.html |

|||

|title=Magnetic Properties |

|title=Magnetic Properties |

||

|publisher=University of Georgia |

|publisher=University of Georgia |

||

|accessdate=2007-01-07 |

|accessdate=2007-01-07 |

||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

}}{{dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref> |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070429150216/http://www.gly.uga.edu/schroeder/geol3010/magnetics.html |

|||

|archivedate=2007-04-29 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

对于[[铁磁性]] |

对于[[铁磁性|铁磁]]元素,例如铁,电子总数为奇数,会产生净磁矩。同时,因为相邻原子轨道重叠等原因,当未成对电子都朝向同一个方向时,体系的总能量最低,这个过程称为[[交换相互作用]]。当这些铁磁性元素的磁动量都统一朝向后,整个材料就会拥有一个宏观可以测量的磁场。[[順磁性|顺磁性]]材料中,在没有外部磁场的情况下,原子磁矩都是随机分布的;施加了外部磁场以后,所有原子都会统一朝向,产生磁场。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Goebel |

|last=Goebel |

||

|first=Greg |

|||

|date=2007-09-01|url=http://www.vectorsite.net/tpqm_04.html |

|date=2007-09-01 |

||

|url=http://www.vectorsite.net/tpqm_04.html |

|||

|title= |

|title=[4.3] Magnetic Properties of the Atom |

||

|work=Elementary Quantum Physics |

|work=Elementary Quantum Physics |

||

|publisher=In The Public Domain website |

|publisher=In The Public Domain website |

||

|accessdate=2007-01-07 |

|accessdate=2007-01-07 |

||

|archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/616Q7pLdl?url=http://www.vectorsite.net/tpqm_04.html |

|||

}}</ref><ref name=schroeder/> |

|||

|archive-date=2011-08-21 |

|||

|dead-url=yes |

|||

}}</ref><ref name=schroeder/> |

|||

原子核也可以存在净自旋。由于[[热平衡]], |

原子核也可以存在净自旋。由于[[热平衡定律|热平衡]],这些原子核通常都随机朝向。但一些元素,例如[[氙]]-129,一部分核自旋也可能[[极化]],这状态叫做[[超极化 (物理学)|超极化]],在[[核磁共振成像]]中有很重要的用途。<ref>{{cite journal |

||

|last=Yarris |

|last=Yarris |

||

|first=Lynn |

|||

|title=Talking Pictures |

|||

|journal=Berkeley Lab Research Review |

|journal=Berkeley Lab Research Review |

||

|year=1997|url=http://www.lbl.gov/Science-Articles/Research-Review/Magazine/1997/story1.html |

|year=1997 |

||

|url=http://www.lbl.gov/Science-Articles/Research-Review/Magazine/1997/story1.html |

|||

|accessdate=2008-01-09 |

|accessdate=2008-01-09 |

||

|author= |

|||

}}</ref><ref>Liang and Haacke (1999:412–26).</ref> |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080113104939/http://www.lbl.gov/Science-Articles/Research-Review/Magazine/1997/story1.html |

|||

|archive-date=2008-01-13 |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

}}</ref><ref>Liang and Haacke (1999:412–26).</ref> |

|||

=== 能-{級 |

=== 能-{zh:級;zh-hans:級;zh-hant:級;zh-cn:级;zh-tw:階;zh-hk:級;zh-sg:級;zh-mo:級;}- === |

||

{{main|能 |

{{main|能級|原子谱线}} |

||

原子中,电子的[[势能]]与它离原子核的距离成反比。测量电子的势能,通常的测量将让该电子脱离原子所需要的能量,单位是[[電子伏特|电子伏特]](eV)。在量子力学模型中,电子只能占据一组以原子核为中心的状态,每一个状态就对应于一个能级。最低的能级就 |

原子中,电子的[[势能]]与它离原子核的距离成反比。测量电子的势能,通常的测量将让该电子脱离原子所需要的能量,单位是[[電子伏特|电子伏特]](eV)。在量子力学模型中,电子只能占据一组以原子核为中心的状态,每一个状态就对应于一个能级。最低的能级就叫做基态,而更高的能级就叫做激发态。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Zeghbroeck |first=Bart J. Van |year=1998|url=http://physics.ship.edu/~mrc/pfs/308/semicon_book/eband2.htm |

|last=Zeghbroeck |

||

|first=Bart J. Van |

|||

|year=1998 |

|||

|url=http://physics.ship.edu/~mrc/pfs/308/semicon_book/eband2.htm |

|||

|title=Energy levels |publisher=Shippensburg University |

|title=Energy levels |

||

|publisher=Shippensburg University |

|||

|accessdate=2007-12-23 |

|accessdate=2007-12-23 |

||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20050115030639/http://physics.ship.edu/~mrc/pfs/308/semicon_book/eband2.htm |

|||

|archivedate=2005-01-15 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

电子要在两个能级之间跃迁的前提是它要吸收或者释放能量,该能量还必须要和这两个能级之间的能量差一致。因为释放的[[光]]子能量只与光子的频率有关,并且能级是不连续的,所以在[[電磁波譜|电磁波谱]]中就会出现一些不连续的带。<ref>Fowles (1989:227–233).</ref>每 |

电子要在两个能级之间跃迁的前提是它要吸收或者释放能量,该能量还必须要和这两个能级之间的能量差一致。因为释放的[[光]]子能量只与光子的频率有关,并且能级是不连续的,所以在[[電磁波譜|电磁波谱]]中就会出现一些不连续的带。<ref>Fowles (1989:227–233).</ref>每種元素都有特征波谱,特征波谱取决于核电荷的多少,电子的填充情况,电子间的电磁相互作用以及一些其他的因素。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Martin |

|last=Martin |

||

|first=W. C. |

|||

|coauthors=Wiese, W. L. |

|coauthors=Wiese, W. L. |

||

|date=2007年5月 |

|||

|url=http://physics.nist.gov/Pubs/AtSpec/ |

|||

|title=Atomic Spectroscopy: A Compendium of Basic Ideas, Notation, Data, and Formulas |

|title=Atomic Spectroscopy: A Compendium of Basic Ideas, Notation, Data, and Formulas |

||

|publisher=National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|publisher=National Institute of Standards and Technology |

||

|accessdate=2007-01-08 |

|accessdate=2007-01-08 |

||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070208113156/http://physics.nist.gov/Pubs/AtSpec/ |

|||

|archive-date=2007-02-08 |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Fraunhofer lines.svg|right|thumb|300px| |

[[File:Fraunhofer lines.svg|right|thumb|300px|吸收谱线的例子:太陽的夫朗和斐譜線]] |

||

当一束全谱的光经过一团气体或者一团等离子体后, |

当一束全谱的光经过一团气体或者一团等离子体后,原子会吸收一些光子,使得这些原子内的电子跃迁。而在激发态的电子则会自发的返回低能态,能量差作为光子释放至随机方向。前者就使那些原子有了类似于滤镜的功能,观测者在最后接收到的光谱中会发现一些黑色的[[吸收频带|吸收能带]]。而后者能够使那些与光线不在同一条直线上的观察者观察到一些不连续的谱线,实际就是那些原子的[[發射譜線|发射谱线]]。用光谱学测量这些谱线就可知该物质的组成以及物理性质。<ref name=>{{cite web |

||

|url=http://www.avogadro.co.uk/light/bohr/spectra.htm |

|url=http://www.avogadro.co.uk/light/bohr/spectra.htm |

||

|title=Atomic Emission Spectra—Origin of Spectral Lines |

|title=Atomic Emission Spectra—Origin of Spectral Lines |

||

|publisher=Avogadro Web Site |

|publisher=Avogadro Web Site |

||

|accessdate=2006-08-10 |

|accessdate=2006-08-10 |

||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20060228231025/http://www.avogadro.co.uk/light/bohr/spectra.htm |

|||

|archivedate=2006-02-28 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

仔细分析谱线后,科学家发现一些谱线有着[[精細結構|精细结构]]的[[裂分]]。这是因为自旋与最外层电子运动间的相互作用,也称作[[自旋-軌道耦合|自旋-轨道耦合]]。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|last=Fitzpatrick |

|last=Fitzpatrick |

||

|first=Richard |

|||

|date=2007-02-16|url=http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/qm/lectures/node55.html |

|date=2007-02-16 |

||

|url=http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/qm/lectures/node55.html |

|||

|title=Fine structure |

|title=Fine structure |

||

|publisher=University of Texas at Austin |

|publisher=University of Texas at Austin |

||

|accessdate=2008-02-14 |

|||

|accessdate=2008-02-14 }}</ref>当原子位于外部磁场中时,谱线能够裂分成三个或多个部分,这个现象被叫做[[塞曼效应]],其原因是原子的磁矩及其电子与外部磁场的相互作用。一些原子拥有许多相同能级电子排布,因而只产生一条谱线。当这些原子被安置在外部[[磁場|磁场]]中时,这几种电子排布的能级就有了一些细小的区别,这样就出现了裂分。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| |

|archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/616Q9bw2M?url=http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/qm/lectures/node55.html |

||

|archive-date=2011-08-21 |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

}}</ref>当原子位于外部磁场中时,谱线能够裂分成三个或多个部分,这现象叫[[塞曼效应]],其原因是原子的磁矩及其电子与外部磁场的相互作用。一些原子拥有许多相同能级电子排布,因而只产生一条谱线。当这些原子安置在外部[[磁場|磁场]]中时,这几种电子排布的能级就有了一些细小区别,这样就出现了裂分。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|last=Weiss |

|||

|first=Michael |

|||

|year=2001 |

|||

|url=http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/spin/node8.html |

|||

|title=The Zeeman Effect |

|title=The Zeeman Effect |

||

|publisher=University of California-Riverside |

|publisher=University of California-Riverside |

||

|accessdate=2008-02-06 |

|accessdate=2008-02-06 |

||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080202143147/http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/spin/node8.html |

|||

}}</ref>外部电场的存在也能导致类似的现象发生,被成为[[斯塔克效应]]。<ref>Beyer (2003:232–236).</ref> |

|||

|archive-date=2008-02-02 |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

}}</ref>外部电场也能导致类似的现象发生,成为[[斯塔克效应]]。<ref>Beyer (2003:232–236).</ref> |

|||

如果一 |

如果一粒电子在激发态,一粒有恰当能量的光子能够使得该电子[[受激辐射]],释放出一粒拥有相同能量的光子,其前提就是电子返回低能级所释放出来的能量必须要与之作用的光子的能量一致。此时,受激释放的光子与原光子向同一个方向运动,也就是说这两粒光子的波是同步的。利用这个原理,人们设计出了[[激光]],用来产生一束拥有很窄频率[[相干性|相干]]光源。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Watkins |

|last=Watkins |

||

|first=Thayer |

|first=Thayer |

||

| 第416行: | 第439行: | ||

|publisher=San José State University |

|publisher=San José State University |

||

|accessdate=2007-12-23 |

|accessdate=2007-12-23 |

||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080112234014/http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/stimem.htm |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

|archive-date=2008-01-12 |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

=== 化合价 === |

=== 化合价 === |

||

{{main|化合价}} |

{{main|化合价}} |

||

单 |

单粒原子的电子层最外层一般称为价层,其中的电子称为[[价电子]]。价电子粒数决定了这原子与其他原子成[[化学键|键]]的性质。原子能发生化学反应的一个统一趋势是使其价层全满或者全空。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Reusch |first=William |date=2007-07-16|url=http://www.cem.msu.edu/~reusch/VirtualText/intro1.htm |

|last=Reusch |

||

|first=William |

|||

|date=2007-07-16 |

|||

|url=http://www.cem.msu.edu/~reusch/VirtualText/intro1.htm |

|||

|title=Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry |

|title=Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry |

||

|publisher=Michigan State University |

|publisher=Michigan State University |

||

|accessdate=2008-01-11 |

|accessdate=2008-01-11 |

||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071029211245/http://www.cem.msu.edu/~reusch/VirtualText/intro1.htm |

|||

|archivedate=2007-10-29 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

[[元素|化学元素]]通常 |

[[元素|化学元素]]通常写在化学周期表中,用来表明它们有周期重复的一些化学性质。通常,拥有相同数量价电子的元素形成一组,在元素周期表中占相同的一列。而元素周期表中的横排则与量子层的电子填充情况相对应。周期表最右边的元素价层都全满,它们在[[化学反应]]中表现出一定的惰性,称为[[稀有气体|惰性气体]]。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|author=Husted, Robert et al |

|author=Husted, Robert et al |

||

|date=2003-12-11 |

|||

|url=http://periodic.lanl.gov/default.htm |

|||

|title=Periodic Table of the Elements |

|title=Periodic Table of the Elements |

||

|publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory |

|publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory |

||

|accessdate=2008-01-11 |

|accessdate=2008-01-11 |

||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080110103232/http://periodic.lanl.gov/default.htm |

|||

</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|||

|archive-date=2008-01-10 |

|||

|first=Rudy |last=Baum |year=2003|url=http://pubs.acs.org/cen/80th/elements.html |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

|title=It's Elemental: The Periodic Table |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |first=Rudy |last=Baum |year=2003 |url=http://pubs.acs.org/cen/80th/elements.html |title=It's Elemental: The Periodic Table |publisher=Chemical & Engineering News |accessdate=2008-01-11 |archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/616QCRYK8?url=http://pubs.acs.org/cen/80th/elements.html |archive-date=2011-08-21 |dead-url=no }}</ref> |

|||

|publisher=Chemical & Engineering News |

|||

|accessdate=2008-01-11 }}</ref> |

|||

=== 态 === |

=== 态 === |

||

| 第450行: | 第484行: | ||

|doi=10.1070/PU2006v049n07ABEH006013 |bibcode= 2006PhyU...49..719B }}</ref> |

|doi=10.1070/PU2006v049n07ABEH006013 |bibcode= 2006PhyU...49..719B }}</ref> |

||

当温度很靠近[[绝对零度]]时,原子可以形成[[玻色-爱因斯坦凝聚|玻 |

当温度很靠近[[绝对零度]]时,原子可以形成[[玻色-爱因斯坦凝聚|玻斯-爱因斯坦凝聚态]]。<ref>Myers (2003:85).</ref><ref>{{cite news |

||

|author=Staff |date=2001-10-09|title=Bose-Einstein Condensate: A New Form of Matter |

|author=Staff |

||

|date=2001-10-09 |

|||

|title=Bose-Einstein Condensate: A New Form of Matter |

|||

|publisher=National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|publisher=National Institute of Standards and Technology |

||

|url=http://www.nist.gov/public_affairs/releases/BEC_background.htm |

|url=http://www.nist.gov/public_affairs/releases/BEC_background.htm |

||

|accessdate=2008-01-16 |

|||

|accessdate=2008-01-16 }}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref>这些超冷的原子可以被视为一个[[超原子]],使得科学家可以研究量子力学的一些基本原理。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|last=Colton |first=Imogen |coauthors=Fyffe, Jeanette |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080103192918/http://www.nist.gov/public_affairs/releases/BEC_background.htm |

|||

|date=1999-02-03|url=http://www.ph.unimelb.edu.au/~ywong/poster/articles/bec.html |

|||

|archivedate=2008-01-03 |

|||

|title=Super Atoms from Bose-Einstein Condensation |

|||

}}</ref>这些超冷的原子可视为[[超原子]],使得科学家可以研究量子力学的一些基本原理。<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|publisher=The University of Melbourne |

|||

|last=Colton |

|||

|accessdate=2008-02-06 }}{{Dead link|date=July 2015}}</ref> |

|||

|first=Imogen |

|||

|coauthors=Fyffe, Jeanette |

|||

|date=1999-02-03 |

|||

|url=http://www.ph.unimelb.edu.au/~ywong/poster/articles/bec.html |

|||

|title=Super Atoms from Bose-Einstein Condensation |

|||

|publisher=The University of Melbourne |

|||

|accessdate=2008-02-06 |

|||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070829200820/http://www.ph.unimelb.edu.au/~ywong/poster/articles/bec.html |

|||

|archivedate=2007-08-29 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== 测定 == |

||

[[File:Atomic resolution Au100. |

[[File:Atomic resolution Au100.JPG|right|250px|thumb|扫描隧道显微镜图片,显示了组成[[金|Au]]([[密勒指数|100]])的单粒金原子。]] |

||

[[扫描隧道显微镜]]是用来在原子 |

[[扫描隧道显微镜]]是用来在原子級數观测物体表面的仪器。它利用了[[量子穿隧效應|量子穿隧效应]],使电子能穿越平时不能克服的障碍。在操作中,电子能够隧穿介于两塊平面金属电极间的真空。每塊电极表面吸附有一粒原子,使得穿隧电流密度大到可以测量。扫描時保持电流恒定,可以得到探针末端上下位移与横向位移间关系的图。计算证明扫描隧道显微镜所得到的显微图像能够分辨出单粒原子。在低偏差的情况下,显微图像显示的是对相近能级的电子轨道的一种空间平均后的尺寸,这些相近的能级也就是[[费米能]]中的[[局部态密度]]。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Jacox |

|last=Jacox |

||

|first=Marilyn |

|||

|coauthors=Gadzuk, J. William |

|||

|url=http://physics.nist.gov/GenInt/STM/stm.html |

|url=http://physics.nist.gov/GenInt/STM/stm.html |

||

|title=Scanning Tunneling Microscope |

|title=Scanning Tunneling Microscope |

||

|publisher=National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|publisher=National Institute of Standards and Technology |

||

|date=1997年11月|accessdate=2008-01-11 |

|date=1997年11月 |

||

|accessdate=2008-01-11 |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080107133132/http://physics.nist.gov/GenInt/STM/stm.html |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|||

|archive-date=2008-01-07 |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1986/index.html |

|url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1986/index.html |

||

|title=The Nobel Prize in Physics 1986 |

|title=The Nobel Prize in Physics 1986 |

||

|publisher=The Nobel Foundation |

|publisher=The Nobel Foundation |

||

|accessdate=2008-01-11 |

|accessdate=2008-01-11 |

||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080917103215/http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1986/index.html |

|||

|archive-date=2008-09-17 |

|||

|dead-url=no |

|||

}}—in particular, see the Nobel lecture by G. Binnig and H. Rohrer.</ref> |

|||

原子失去电子时就[[电离]]了。这多余的电荷會偏折它在磁场运行的轨迹。这偏转角度由原子质量决定。[[质谱|质谱仪]]就用这原理测定离子的[[荷质比|质荷比]]。如果样品里有多种同位素,质谱可以通过测量不同离子束的强度来推导同位素的比例。使原子气化的技术包括[[电感耦合等离子体原子发射光谱]]以及[[电感耦合等离子体质谱法]]。这两种技术都使用了气态或等离子态的样品。<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|first=N. |last=Jakubowski |

|first=N. |last=Jakubowski |

||

|coauthors= Moens, L.; Vanhaecke, F |

|coauthors= Moens, L.; Vanhaecke, F |

||

| 第483行: | 第540行: | ||

|volume= 53 |issue= 13 |year=1998|doi=10.1016/S0584-8547(98)00222-5 |pages= 1739–63|bibcode= 1998AcSpe..53.1739J }}</ref> |

|volume= 53 |issue= 13 |year=1998|doi=10.1016/S0584-8547(98)00222-5 |pages= 1739–63|bibcode= 1998AcSpe..53.1739J }}</ref> |

||

另 |

另一有侷限的方法是[[电子能量损失谱]],它是通过测量透射电子显微镜中电子束穿越一个样品后所损失的能量。{{le|原子探针|Atom probe|原子探针显像}}具有三维亚纳米级的分辨率,也可以通过{{le|飞行时间质谱仪|Time-of-flight mass spectrometry}}来鉴定单粒的原子。<ref>{{cite journal |

||

|last=Müller |first=Erwin W. |

|last=Müller |first=Erwin W. |

||

|authorlink=Erwin Müller |

|authorlink=Erwin Müller |

||

| 第492行: | 第549行: | ||

|issn=0034-6748 |doi=10.1063/1.1683116 |bibcode= 1968RScI...39...83M }}</ref> |

|issn=0034-6748 |doi=10.1063/1.1683116 |bibcode= 1968RScI...39...83M }}</ref> |

||

[[激发态光谱 |

[[激发态]]光谱可以用来研究远距离[[恒星]]的元素组成。观测来自恒星的光谱中特殊的波长,可以得到气体状态下原子的量子转变。使用同种元素的[[氣體放電燈|气体放电灯]],可以得到相同的颜色。<ref>{{cite web |

||

|last=Lochner |

|last=Lochner |

||

|first=Jim |

|||

|coauthors=Gibb, Meredith; Newman, Phil |

|coauthors=Gibb, Meredith; Newman, Phil |

||

|date=2007-04-30|url=http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/how_l1/spectral_what.html |

|date=2007-04-30 |

||