锑:修订间差异

TuhansiaVuoria(留言 | 贡献) 小 →历史: 增加或调整内部链接 |

|||

| 第194行: | 第194行: | ||

=== 名稱來源 === |

=== 名稱來源 === |

||

現代語言和[[中古希腊语|中古希臘語]]中銻的名稱antimony是來自中世紀拉丁語的antimonium。這個說法的來源不可考。所有的說法都有一些難以解釋的地方。其他名稱來源的說法像是:銻名稱可能來自於'''ἀντίμοναχός''' '''anti-monachos'''或法文'''antimoine'''。這些名稱來源是因為早期[[炼金术|煉金]]的修士們還有銻的毒性,而被稱為「反」 |

現代語言和[[中古希腊语|中古希臘語]]中銻的名稱antimony是來自中世紀拉丁語的antimonium。這個說法的來源不可考。所有的說法都有一些難以解釋的地方。其他名稱來源的說法像是:銻名稱可能來自於'''ἀντίμοναχός''' '''anti-monachos'''或法文'''antimoine'''。這些名稱來源是因為早期[[炼金术|煉金]]的修士們還有銻的毒性,而被稱為「反」(Anti-)「修士」(Monk),也就是修士剋星。<ref name="#1">{{Cite journal|title=Online etymology dictionary|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/choice.41-0659|date=2003-10-01|journal=Choice Reviews Online|issue=02|doi=10.5860/choice.41-0659|volume=41|pages=41–0659-41-0659|issn=0009-4978}}</ref> |

||

另一個常見的名稱來源是希臘語'''ἀντίμόνος'''(antimonos)表示「對抗孤獨」,可以解釋為「未被以金屬形式發現」或「未被發現為無雜質的」。<ref>{{Cite book|edition=5th|title=Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology.|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/53178503|publisher=Hoboken, N.J.|isbn=9780471484943|oclc=53178503|author1=Kroschwitz, Jacqueline I.|author2=Seidel, Arza.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=How Hooker found his boogie: a rhythmic analysis of a classic groove|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0261143008001578|last=BENADON|first=FERNANDO|last2=GIOIA|first2=TED|date=2009-01|journal=Popular Music|issue=1|doi=10.1017/s0261143008001578|volume=28|pages=19–32|issn=0261-1430}}</ref> Lippmann推測一假設的希臘語'''ανθήμόνιον'''(anthemonion)表示「小花」,並引用了幾個描述化學或生物風化的相關希臘詞的例子。<ref>{{Cite book|chapter=Gender and Media: Content, Uses, and Impact|title=Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1467-5_27|publisher=Springer New York|date=2009-12-04|location=New York, NY|isbn=9781441914668|pages=643–669|first=Dara N.|last=Greenwood|first2=Julia R.|last2=Lippman}}</ref> |

另一個常見的名稱來源是希臘語'''ἀντίμόνος'''(antimonos)表示「對抗孤獨」,可以解釋為「未被以金屬形式發現」或「未被發現為無雜質的」。<ref>{{Cite book|edition=5th|title=Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology.|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/53178503|publisher=Hoboken, N.J.|isbn=9780471484943|oclc=53178503|author1=Kroschwitz, Jacqueline I.|author2=Seidel, Arza.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=How Hooker found his boogie: a rhythmic analysis of a classic groove|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0261143008001578|last=BENADON|first=FERNANDO|last2=GIOIA|first2=TED|date=2009-01|journal=Popular Music|issue=1|doi=10.1017/s0261143008001578|volume=28|pages=19–32|issn=0261-1430}}</ref> Lippmann推測一假設的希臘語'''ανθήμόνιον'''(anthemonion)表示「小花」,並引用了幾個描述化學或生物風化的相關希臘詞的例子。<ref>{{Cite book|chapter=Gender and Media: Content, Uses, and Impact|title=Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1467-5_27|publisher=Springer New York|date=2009-12-04|location=New York, NY|isbn=9781441914668|pages=643–669|first=Dara N.|last=Greenwood|first2=Julia R.|last2=Lippman}}</ref> |

||

| 第200行: | 第200行: | ||

銻的早期使用包含1050至1100年時的翻譯文件,由非洲君士坦丁書寫的阿拉伯醫學論文翻譯。<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Writing That Says Nothing|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199314645.003.0009|last=Pouillaude|first=Frédéric|date=2017-06-22|journal=Oxford Scholarship Online|doi=10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199314645.003.0009}}</ref>一些當局認為銻之名稱來自於某些阿拉伯腐敗的相關名詞,是麥爾侯夫從ithmid中得知;<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Schröder Asserts the German National Interest, 1999–2003|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199351381.003.0004|last=Mody|first=Ashoka|date=2018-05-24|journal=Oxford Scholarship Online|doi=10.1093/oso/9780199351381.003.0004}}</ref>其他可能性包括非金屬的阿拉伯語athimar以及源自於或平行於希臘語as-stimmi。<ref>{{Cite book|chapter=Introduction “The Angel Would Like to Stay, Awaken the Dead, and Make Whole What Has Been Smashed”|title=Black and White Manhattan|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195165371.003.0001|publisher=Oxford University Press|date=2004-11-18|isbn=9780195165371|pages=3–20|first=THELMA WILLS|last=FOOTE}}</ref> [[永斯·贝采利乌斯|Jöns Jakob Berzelius]]自stibium中得出銻的標準元素符號Sb。<ref>{{Cite book|title=A view of the progress and present state of animal chemistry (translated from the Swedish by Gustavus Brunnmark)|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.30007|publisher=Printed by J. Skirven and sold by J. Hatchard, J. Johnson, and T. Boosey|year=1813|location=London|first=Jöns Jakob|last=Berzelius}}</ref>銻的古代詞語主要以銻的硫化物為主要含義。 |

銻的早期使用包含1050至1100年時的翻譯文件,由非洲君士坦丁書寫的阿拉伯醫學論文翻譯。<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Writing That Says Nothing|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199314645.003.0009|last=Pouillaude|first=Frédéric|date=2017-06-22|journal=Oxford Scholarship Online|doi=10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199314645.003.0009}}</ref>一些當局認為銻之名稱來自於某些阿拉伯腐敗的相關名詞,是麥爾侯夫從ithmid中得知;<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Schröder Asserts the German National Interest, 1999–2003|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199351381.003.0004|last=Mody|first=Ashoka|date=2018-05-24|journal=Oxford Scholarship Online|doi=10.1093/oso/9780199351381.003.0004}}</ref>其他可能性包括非金屬的阿拉伯語athimar以及源自於或平行於希臘語as-stimmi。<ref>{{Cite book|chapter=Introduction “The Angel Would Like to Stay, Awaken the Dead, and Make Whole What Has Been Smashed”|title=Black and White Manhattan|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195165371.003.0001|publisher=Oxford University Press|date=2004-11-18|isbn=9780195165371|pages=3–20|first=THELMA WILLS|last=FOOTE}}</ref> [[永斯·贝采利乌斯|Jöns Jakob Berzelius]]自stibium中得出銻的標準元素符號Sb。<ref>{{Cite book|title=A view of the progress and present state of animal chemistry (translated from the Swedish by Gustavus Brunnmark)|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.30007|publisher=Printed by J. Skirven and sold by J. Hatchard, J. Johnson, and T. Boosey|year=1813|location=London|first=Jöns Jakob|last=Berzelius}}</ref>銻的古代詞語主要以銻的硫化物為主要含義。 |

||

埃及人稱銻為'''mśdmt'''<ref>{{Cite journal|title=(Al-morchid fi'l-kohhl) ou Le guide d'oculistique. Max Meyerhof|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/346926|last=Sarton|first=George|date=1935-02|journal=Isis|issue=2|doi=10.1086/346926|volume=22|pages=539–542|issn=0021-1753}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=Notes on Egypto-Semitic Etymology. II|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/369866|last=Albright|first=W. F.|date=1918-07|journal=The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures|issue=4|doi=10.1086/369866|volume=34|pages=215–255|issn=1062-0516}}</ref>,在象形文字中此處母音不確定,但是在科普特語中是'''ⲥⲧⲏⲙ''' |

埃及人稱銻為'''mśdmt'''<ref>{{Cite journal|title=(Al-morchid fi'l-kohhl) ou Le guide d'oculistique. Max Meyerhof|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/346926|last=Sarton|first=George|date=1935-02|journal=Isis|issue=2|doi=10.1086/346926|volume=22|pages=539–542|issn=0021-1753}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=Notes on Egypto-Semitic Etymology. II|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/369866|last=Albright|first=W. F.|date=1918-07|journal=The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures|issue=4|doi=10.1086/369866|volume=34|pages=215–255|issn=1062-0516}}</ref>,在象形文字中此處母音不確定,但是在科普特語中是'''ⲥⲧⲏⲙ''' (stēm)。而希臘語'''στίμμι stimmi'''可能是來自阿拉伯或埃及的[[外來語]]<ref name="#1"/>。 |

||

並被公元前5世紀的雅典悲劇詩人使用。後來在公元一世紀,希臘人也使用'''στἰβι'''輝銻礦,而[[凯尔苏斯|凱爾蘇斯]]和[[老普林尼]]亦如此。此外,老普林尼也給了它stimi [''sic'']、larbaris、[[雪花石膏]](Alabaster)、“非常平凡的” platyophthalmos“、”放大的眼睛 |

並被公元前5世紀的雅典悲劇詩人使用。後來在公元一世紀,希臘人也使用'''στἰβι'''輝銻礦,而[[凯尔苏斯|凱爾蘇斯]]和[[老普林尼]]亦如此。此外,老普林尼也給了它stimi [''sic'']、larbaris、[[雪花石膏]](Alabaster)、“非常平凡的” platyophthalmos“、”放大的眼睛“(來自化妝品的效果) 的名字。後來拉丁人作者將這個詞改為拉丁語的銻,為「物質」的阿拉伯語,相對於「化妝品」的,可以以'''إثمد''' ithmid、athmoud、othmod或uthmod的形式出現。[[埃米勒·利特雷]]提議出最早來自stimmida<ref>{{Cite web|title=Celsus|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2214-8647_bnps2_com_0060|accessdate=2019-09-28|work=Brill’s New Pauly Supplements I - Volume 2 : Dictionary of Greek and Latin Authors and Texts}}</ref>的第一個形式,是stimmi的直接受格。 |

||

== 生产 == |

== 生产 == |

||

| 第381行: | 第381行: | ||

===供應風險=== |

===供應風險=== |

||

對於歐洲和美國等銻進口地區,銻被認為是存在供應鏈中斷風險的工業製造關鍵礦物。由於全球產量主要來自中國 |

對於歐洲和美國等銻進口地區,銻被認為是存在供應鏈中斷風險的工業製造關鍵礦物。由於全球產量主要來自中國 (74%)、塔吉克斯坦 (8%) 和俄羅斯 (4%),這些來源對供應至關重要。 |

||

<ref name="EU Raw 2020">{{cite web|date=2020|title=Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability|url=https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/42849|access-date=2 February 2022|publisher=European Commission|archive-date=2023-09-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230920053156/https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/42849|dead-url=no}}</ref><ref name="Nassar SciAdv 2020">{{cite journal |last=Nassar |first=Nedal T. |display-authors=etal |date=2020-02-21 |title=Evaluating the mineral commodity supply risk of the U.S. manufacturing sector |journal=Sci. Adv. |volume=6 |issue=8 |page=eaay8647 |bibcode=2020SciA....6.8647N |doi=10.1126/sciadv.aay8647 |issn=2375-2548 |pmc=7035000 |pmid=32128413}}</ref>隨著中國正在修訂及提升環境管制標準,銻的生產越來越受到限制,這導致了中國過去幾年的銻出口配額也一直下降。此外,中美之間的地緣政治緊張關係,也令到歐洲及美國的銻供應風險增加。 |

<ref name="EU Raw 2020">{{cite web|date=2020|title=Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability|url=https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/42849|access-date=2 February 2022|publisher=European Commission|archive-date=2023-09-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230920053156/https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/42849|dead-url=no}}</ref><ref name="Nassar SciAdv 2020">{{cite journal |last=Nassar |first=Nedal T. |display-authors=etal |date=2020-02-21 |title=Evaluating the mineral commodity supply risk of the U.S. manufacturing sector |journal=Sci. Adv. |volume=6 |issue=8 |page=eaay8647 |bibcode=2020SciA....6.8647N |doi=10.1126/sciadv.aay8647 |issn=2375-2548 |pmc=7035000 |pmid=32128413}}</ref>隨著中國正在修訂及提升環境管制標準,銻的生產越來越受到限制,這導致了中國過去幾年的銻出口配額也一直下降。此外,中美之間的地緣政治緊張關係,也令到歐洲及美國的銻供應風險增加。 |

||

<ref name="Roskill" /> |

<ref name="Roskill" /> |

||

==== 英国 ==== |

==== 英国 ==== |

||

英国地质调查局在2011年下半年将锑列在风险列表第一位。这个列表表示如果化学元素不能稳定供应,会对维持英国经济和生活方式造成的相对风险。<ref>{{cite web|title=British Geologocal Survey - Risk List|url=http://www.bgs.ac.uk/mineralsuk/statistics/riskList.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110923163328/http://www.bgs.ac.uk/mineralsuk/statistics/risklist.html|archive-date=2011-09-23|accessdate=2012-07-03|dead-url=yes}}</ref> |

英国地质调查局在2011年下半年将锑列在风险列表第一位。这个列表表示如果化学元素不能稳定供应,会对维持英国经济和生活方式造成的相对风险。<ref>{{cite web|title=British Geologocal Survey - Risk List|url=http://www.bgs.ac.uk/mineralsuk/statistics/riskList.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110923163328/http://www.bgs.ac.uk/mineralsuk/statistics/risklist.html|archive-date=2011-09-23|accessdate=2012-07-03|dead-url=yes}}</ref>2015年[[英国地质调查局]]風險列表,銻在相對供應風險指數中排名第二(僅次於稀土元素)。<ref>{{Cite book|chapter=List of Contributors|title=Coastal Risk Management in a Changing Climate|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-397310-8.01002-2|publisher=Elsevier|date=2015|isbn=9780123973108|pages=xiii–xxxi}}</ref> 這指出它目前是對於英國經濟和生活方式具有經濟價值的化學元素或元素群的第二高供應風險。此外,在2014年發布的一份報告(修訂了2011年發布的初始報告)中,銻被確定為歐盟20種關鍵原材料之一。相對於其經濟重要性,銻保持著高供應風險,92%的銻是從中國進口的,此為一個極高的生產集中度。<ref>{{Cite journal |date=2015-02 |title=Phosphate rock in EU list of 20 critical raw materials |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1351-4210(15)30009-3 |journal=Focus on Surfactants |volume=2015 |issue=2 |pages=4 |doi=10.1016/s1351-4210(15)30009-3 |issn=1351-4210}}</ref> |

||

==== 欧盟 ==== |

==== 欧盟 ==== |

||

欧盟在2011年的一份报告中也将锑列为12种关键的原料之一,主要是因为来自中国以外的锑产量很少。<ref>{{cite news|last=Khrennikov|first=Ilya|title=Russian Antimony Miner for iPads Looks at IPO to Challenge China|url=http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-03-05/russian-antimony-miner-for-ipads-looks-at-ipo-to-challenge-china.html|date=2012-03-05|accessdate=2012-07-03|archive-date=2012-05-08|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120508073746/http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-03-05/russian-antimony-miner-for-ipads-looks-at-ipo-to-challenge-china.html|dead-url=no}}</ref>銻被認為是國防、汽車、建築和紡織品的重要原材料。 歐盟成員國境內沒有開採锑,因此是完全依賴進口,主要來自土耳其 |

欧盟在2011年的一份报告中也将锑列为12种关键的原料之一,主要是因为来自中国以外的锑产量很少。<ref>{{cite news|last=Khrennikov|first=Ilya|title=Russian Antimony Miner for iPads Looks at IPO to Challenge China|url=http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-03-05/russian-antimony-miner-for-ipads-looks-at-ipo-to-challenge-china.html|date=2012-03-05|accessdate=2012-07-03|archive-date=2012-05-08|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120508073746/http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-03-05/russian-antimony-miner-for-ipads-looks-at-ipo-to-challenge-china.html|dead-url=no}}</ref>銻被認為是國防、汽車、建築和紡織品的重要原材料。 歐盟成員國境內沒有開採锑,因此是完全依賴進口,主要來自土耳其 (62%)、玻利維亞 (20%) 和危地馬拉 (7%)。<ref name="EU Raw 20202">{{cite web|date=2020|title=Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability|url=https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/42849|access-date=2 February 2022|publisher=European Commission|archive-date=2023-09-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230920053156/https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/42849|dead-url=no}}</ref> |

||

==== 美國 ==== |

==== 美國 ==== |

||

銻被美國被認為是一種對經濟和國家安全至關重要的礦產商品。美國關鍵和戰略礦產供應鏈小組委員會 |

銻被美國被認為是一種對經濟和國家安全至關重要的礦產商品。美國關鍵和戰略礦產供應鏈小組委員會(Subcommittee on Critical and Strategic Mineral Supply Chains)從1996年至2008年篩選了78種礦產資源,發現包括銻在內的一小部分礦物一直屬於潛在的關鍵礦物類別。在未來將對已發現的礦物子集進行第二次評估,以確定哪些礦產應該被定義為重大風險且對美國的利益至關重要。<ref>{{Cite journal |title=General method to declare the use of critical raw materials in energy-related products |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.3403/30373793 |publisher=BSI British Standards}}</ref>從2011年到2014年,美國68%的銻來自中國,14%來自印度,4%來自墨西哥,14%來自其他地方,而目前沒有公開美國政府的庫存量。<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Purcell |first=Arthur |date=1978-06 |title=Conference report |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0301-4207(78)90019-3 |journal=Resources Policy |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=146 |doi=10.1016/0301-4207(78)90019-3 |issn=0301-4207}}</ref>截止2021年,美國本土並未開採任何銻。<ref name=""USGS 2022">{{cite web|last1=U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2022|title=Antimony|url=https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022-antimony.pdf|url-status=live|archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022-antimony.pdf|archive-date=2022-10-09|access-date=1 February 2022}}</ref> |

||

== 应用 == |

== 应用 == |

||

2024年12月5日 (四) 03:34的最新版本

几十年以来,中国已成为世界上最大的锑及其化合物生产国,而其中大部分又都产自湖南省冷水江市的锡矿山。[8]锑的工业制法是先焙烧,再用碳在高温下还原,或者是直接用金属铁还原辉锑矿。[9]

金属锑最大的用途是与铅和锡制作合金,以及铅酸电池中所用的铅锑合金板。锑与铅和锡制成合金可用来提升焊接材料、子弹及轴承的性能。[10]锑化合物是用途广泛的含氯及含溴阻燃剂的重要添加剂。锑在新兴的微电子技术也有用途。[11]

特点

[编辑]性质

[编辑]

锑是氮族元素(15族),电负性为2.05,有反磁性,根据元素周期律,它的电负性比锡和铋大,比碲和砷小。锑在室温下的空气中是稳定的,但加热时能与氧气反应生成三氧化二锑。[12]:758

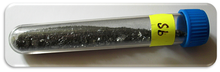

锑是一种带有银色光泽的灰色金属,其莫氏硬度为3。因此,纯锑不能用于制造硬的物件:中国的贵州省曾在1931年发行锑制的硬币,但因为锑很容易磨损,在流通过程损失严重。[13][14]锑會與稀硝酸或溫暖的濃硫酸發生化學反應。[15]

锑在标准情况下只有一种稳定的同素异形体——金属锑。[16]金属锑是一种易碎的银白色有光泽的金属。把熔融的锑缓慢冷却,金属锑就会结成三方晶系的晶体,其结构与砷、铋相同。黑锑是由金属锑的蒸汽急剧冷却形成,只能以厚度只有几纳米的薄膜形式稳定存在,更厚时就会自发变成金属锑。[17]它的晶体结构与红磷和黑砷相同[來源請求],在氧气中易被氧化甚至自燃。当100 °C时,它逐渐转变成稳定的金属锑。罕见的爆炸性锑可由电解三氯化锑制得,其中含有相当量的杂质氯,因此不算是锑的同素异形体。[18]用尖锐的器具刮擦它就会发生放热的化学反应,放出白烟并生成金属锑。如果在研钵中用研杵将它磨碎,就会发生剧烈的爆炸。黄锑只能由锑化氢在−90 °C下氧化而得,它同样不是纯锑,所以也不算是锑的同素异形体。[18][19]它在超过−90 °C时及环境光线的作用下,会转化成更稳定的黑锑。[20][21][22]

金属锑的结构为层状结构(空间群:R3m No. 166),而每层都包含相连的褶皱六元环结构。最近的和次近的锑原子形成变形八面体,在相同双层中的三个锑原子比其他三个相距略近一些。这种距离上的相对近使得金属锑的密度达到6.697 g/cm3,但层与层之间的成键很弱也造成它很软且易碎。[12]:758

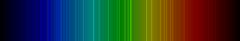

同位素

[编辑]锑有两种稳定同位素,121Sb的自然丰度为57.36%,而123Sb的自然丰度为42.64%。锑还有35种放射性同位素,其中半衰期最长的125Sb为2.75年。此外,目前已发现了29种亚稳态。这其中最稳定的是124Sb,半衰期为60.20天,它可以用作中子源。比稳定同位素123Sb轻的同位素倾向于发生β+衰变,而较重的同位素更易发生β-衰变。当然也有一些例外。[23]

自然存在

[编辑]

锑在地壳中的丰度估计为百万分之0.2至0.5,与之接近的是铊(0.5ppm)和银(0.07ppm)。[24]尽管这种元素并不丰富,但它依然在超过一百种矿物中存在。虽然自然界中会有一些锑单质存在,但多数锑依然存在于它最主要的矿石——辉锑矿(主要成分Sb2S3)中。[24]

化合物

[编辑]锑化合物通常分为+3价和+5价两类。[25]

氧化物与氢氧化物

[编辑]三氧化二锑可由锑在空气中燃烧制得。[26]在气相中,它以双聚体Sb

4O

6的形式存在,但冷凝时会形成多聚体。[12]五氧化二锑只能用浓硝酸氧化三价锑化合物制得。[27]锑也能形成混合价态化合物——四氧化二锑,其中的锑为Sb(III)和Sb(V)。[27]与磷和砷不同的是,这些氧化物都是两性的,它们不形成定义明确的含氧酸,而是与酸反应形成锑盐。

目前还没有制得亚锑酸(Sb(OH)

3),但它的共轭碱亚锑酸钠([Na

3SbO

3]

4)可由熔融的氧化钠与三氧化二锑反应制得。[12]:763过渡金属的亚锑酸盐也已制得。[28]:122锑酸只能以水合物HSb(OH)

6的形式存在,它形成的盐中含有Sb(OH)6−。这些盐脱水得到混合氧化物。[28]:143

许多锑矿石是硫化物,其中如辉锑矿(Sb

2S

3)、深红银矿(Ag

3SbS

3)、辉锑铅矿、脆硫锑铅矿和硫锑铅矿。[12]:757五硫化二锑是一种非整比化合物,锑处于+3氧化态并含有S-S键。[29]有多种硫代锑酸盐是已知的,例如[Sb

6S

10]2−

和[Sb

8S

13]2−

。[30]

卤化物

[编辑]锑能形成两类卤化物——SbX

3和SbX

5。其中三卤化物(SbF

3、SbCl

3、SbBr

3和SbI

3)的空间构型都是三角锥形。三氟化锑可以由三氧化二锑与氢氟酸反应制得:[12]:761–762

- Sb

2O

3 + 6 HF → 2 SbF

3 + 3 H

2O

这种氟化物是路易斯酸,能结合氟离子形成配离子SbF−

4和SbF2−

5。熔化的三氟化锑是一种弱的导体。三氯化锑则由三硫化二锑溶于盐酸制得:[31]:56

- Sb

2S

3 + 6 HCl → 2 SbCl

3 + 3 H

2S

五卤化物(SbF

5和SbCl

5)气态时的空间构型为三角双锥形。但是转化为液态后,五氟化锑形成聚合物,而五氯化锑依旧是单体。[12]:761五氟化锑是很强的路易斯酸,可用于配制著名的超强酸氟锑酸(HSbF6)。

锑的卤氧化物比砷和磷更为常见。三氧化二锑溶于浓酸再稀释可形成锑酰化合物,例如SbOCl和(SbO)

2SO

4。[12]:764

锑化物、氢化物与有机锑化合物

[编辑]这类化合物通常被视作Sb3-的衍生物。锑能与金属形成锑化物,例如锑化铟(InSb)和锑化银(Ag

3Sb)。[12]:760碱金属和锌的锑化物,例如Na3Sb和Zn3Sb2比前者更为活泼。这些锑化物用酸处理可以生成不稳定的气体锑化氢(SbH

3):[32]

- Sb3−

+ 3 H+

→ SbH

3

锑化氢也可用活泼氢化物(如硼氢化钠)还原三价锑化合物来制备。它在室温下就会自发分解,因为它的标准摩尔生成焓为正值。正因为如此,它在热力学上不稳定,不能由锑和氢气直接化合制得。[25]

有机锑化合物一般可由格氏试剂对卤化锑的烷基化反应制备。[33]已知有超過3,000種有机锑化合物[34],包括混合氯代衍生物,还有以锑为中心的阳离子和阴离子。例如Sb(C6H5)3(三苯基锑)、Sb2(C6H5)4(含有一根Sb-Sb键)以及环状的[Sb(C6H5)]n。五配位的有机锑化合物也很常见,例如Sb(C6H5)5和一些类似的卤代物。

历史

[编辑]

早在公元前3100年的古埃及前王朝時期,化妆品刚被发明,三硫化二锑就用作化妆用的眼影粉。[5]

在迦勒底的泰洛赫(今伊拉克),曾发现一块可追溯到公元前3000年的锑制史前花瓶碎片;而在埃及发现了公元前2500年至前2200年间的镀锑的铜器。[20]奥斯汀在1892年赫伯特·格拉斯顿的一场演讲时[35]说道:“我们只知道锑现在是一种很易碎的金属,很难被塑造成实用的花瓶,因此这项值得一提的发现(即上文的花瓶碎片)表现了已失传的使锑具有可塑性的方法。”[注 1][35]然而,默里(Moorey)不相信那个碎片真的来自花瓶,在1975年发表他的分析论文后,认为瑟里姆卡诺夫(Selimkhanov)试图将那块金属与外高加索的天然锑联系起来,但用那种材料制成的都是小饰物。[35]这大大削弱了锑在古代技术下具有可塑性这种说法的可信度。[35]

欧洲人万诺乔·比林古乔于1540年最早在《火法技艺》(De la pirotechnia)中描述了提炼锑的方法,这早于1556年格奥尔格·阿格里科拉出版的名作《论矿冶》(De re Metallica)。此书中阿格里科拉错误地记入了金属锑的发现。1604年,德国出版了一本名为《Currus Triumphalis Antimonii》(直译为“凯旋战车锑”)的书,其中介绍了金属锑的制备。15世纪时,本笃会修士巴西利厄斯·华伦提努提到了锑的制法,如果此事属实,就早于比林古乔。[注 2][21][37]

一般认为,纯锑是由贾比尔(Jābir ibn Hayyān)于8世纪时最早制得的。然而争议依旧不断,翻译家马塞兰·贝特洛声称贾比尔的书里没有提到锑,但其他人认为[21][38]贝特洛只翻译了一些不重要的著作,而最相关的那些(可能描述了锑)还没翻译,它们的内容至今还是未知的。[39]

地壳中自然存在的纯锑最早是由瑞典科学家和矿区工程师安东·冯·斯瓦伯于1783年记载的。品种样本采集自瑞典西曼兰省萨拉市镇的萨拉银矿。[7][40]

名稱來源

[编辑]現代語言和中古希臘語中銻的名稱antimony是來自中世紀拉丁語的antimonium。這個說法的來源不可考。所有的說法都有一些難以解釋的地方。其他名稱來源的說法像是:銻名稱可能來自於ἀντίμοναχός anti-monachos或法文antimoine。這些名稱來源是因為早期煉金的修士們還有銻的毒性,而被稱為「反」(Anti-)「修士」(Monk),也就是修士剋星。[41]

另一個常見的名稱來源是希臘語ἀντίμόνος(antimonos)表示「對抗孤獨」,可以解釋為「未被以金屬形式發現」或「未被發現為無雜質的」。[42][43] Lippmann推測一假設的希臘語ανθήμόνιον(anthemonion)表示「小花」,並引用了幾個描述化學或生物風化的相關希臘詞的例子。[44]

銻的早期使用包含1050至1100年時的翻譯文件,由非洲君士坦丁書寫的阿拉伯醫學論文翻譯。[45]一些當局認為銻之名稱來自於某些阿拉伯腐敗的相關名詞,是麥爾侯夫從ithmid中得知;[46]其他可能性包括非金屬的阿拉伯語athimar以及源自於或平行於希臘語as-stimmi。[47] Jöns Jakob Berzelius自stibium中得出銻的標準元素符號Sb。[48]銻的古代詞語主要以銻的硫化物為主要含義。

埃及人稱銻為mśdmt[49][50],在象形文字中此處母音不確定,但是在科普特語中是ⲥⲧⲏⲙ (stēm)。而希臘語στίμμι stimmi可能是來自阿拉伯或埃及的外來語[41]。

並被公元前5世紀的雅典悲劇詩人使用。後來在公元一世紀,希臘人也使用στἰβι輝銻礦,而凱爾蘇斯和老普林尼亦如此。此外,老普林尼也給了它stimi [sic]、larbaris、雪花石膏(Alabaster)、“非常平凡的” platyophthalmos“、”放大的眼睛“(來自化妝品的效果) 的名字。後來拉丁人作者將這個詞改為拉丁語的銻,為「物質」的阿拉伯語,相對於「化妝品」的,可以以إثمد ithmid、athmoud、othmod或uthmod的形式出現。埃米勒·利特雷提議出最早來自stimmida[51]的第一個形式,是stimmi的直接受格。

生产

[编辑]

生产国

[编辑]根据英国地质调查局2005年的报告,中华人民共和国是世界上锑产量最大的国家,占了全球的84%,远远超出其后的南非、玻利维亚和塔吉克斯坦。湖南省冷水江市的锡矿山是世界最大锑矿,估计储量为210万吨。[8]

2010年,根据美国地质调查局的报告,中国生产的锑占全球的88.9%。2016年,中国锑产量下降至76.9%,其次是俄羅斯6.9%和塔吉克斯坦6.2%。[52]

| 国家 | 产量(吨) | 占比(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 100,000 | 76.9 | |

| 9,000 | 6.9 | |

| 8,000 | 6.2 | |

| 4,000 | 3.1 | |

| 3,500 | 2.7 | |

| 以上五国总计 | 124,500 | 95.8 |

| 世界总计 | 130,000 | 100.0 |

中國之後的銻產量持續下降,因為中國政府為了控制污染,關閉了多個礦山和冶煉廠。2015年1月,中國開始實施的環保法和修訂後的《錫、銻、汞污染物排放標準》,銻開採的經濟生產變得門檻更高。 根據中國國家統計局的數據,截至2015年9月,湖南省(中國銻儲量最大的省份)有超過50%的銻產能未被有使用。[53][54]根据洛斯基公司的报告,2010年起中国的锑产量開始减少,并且在未来一段时间不可能上升,因為中国已没有开发開採時間達十年左右的重要锑矿床。[55]

以下是洛斯基公司提供的2010年世界锑的主要生产者:

| 国家 | 公司 | 产量(吨/年) |

|---|---|---|

| 曼德勒资源 | 2,750 | |

| 许多 | 5,460 | |

| 比弗·布鲁克 | 6,000 | |

| 锡矿山闪星锑业 | 55,000 | |

| 湖南郴州矿业 | 20,000 | |

| 华锡集团 | 20,000 | |

| 沈阳华昌锑业 | 15,000 | |

| Kazzinc | 1,000 | |

| Kadamdzhai | 500 | |

| SRS | 500 | |

| 美国锑业 | 70 | |

| 许多 | 6,000 | |

| GeoProMining | 6,500 | |

| 默奇森联合公司 | 6,000 | |

| Unzob | 5,500 | |

| 未知 | 600 | |

| Cengiz & Özdemir Antimuan Madenleri | 2,400 |

储量

[编辑]| 国家 | 储量(吨) | 占比(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 950,000 | 47.81 | |

| 350,000 | 17.61 | |

| 310,000 | 15.60 | |

| 140,000 | 7.05 | |

| 60,000 | 3.02 | |

| 50,000 | 2.52 | |

| 27,000 | 1.36 | |

| 其它国家 | 100,000 | 5.03 |

| 世界总计 | 1,987,000 | 100.0 |

生产过程

[编辑]从矿石中提取锑的方法取决于矿石的质量与成分。大部分锑以硫化物矿石形式存在。低品位矿石可用泡沫浮选的方法富集,而高品位矿石加热到500–600 °C使辉锑矿熔化,并得以从脉石中分离出来。锑可以用铁屑从天然硫化锑中还原并分离出来:[9]

- Sb

2S

3 + 3 Fe → 2 Sb + 3 FeS

三硫化二锑比三氧化二锑稳定,因此易于转化,而焙烧后又恢复成硫化物。[10]这种材料直接用于许多应用中,可能产生的杂质是砷和硫化物。[57][58] 将锑从氧化物中提取出来可使用碳的热还原法:[9][57]

- 2 Sb

2O

3 + 3 C → 4 Sb + 3 CO

2

低品位的矿石在高炉中还原,而高品位的则在反射炉中还原。[9]

供應風險

[编辑]對於歐洲和美國等銻進口地區,銻被認為是存在供應鏈中斷風險的工業製造關鍵礦物。由於全球產量主要來自中國 (74%)、塔吉克斯坦 (8%) 和俄羅斯 (4%),這些來源對供應至關重要。 [59][60]隨著中國正在修訂及提升環境管制標準,銻的生產越來越受到限制,這導致了中國過去幾年的銻出口配額也一直下降。此外,中美之間的地緣政治緊張關係,也令到歐洲及美國的銻供應風險增加。 [55]

英国

[编辑]英国地质调查局在2011年下半年将锑列在风险列表第一位。这个列表表示如果化学元素不能稳定供应,会对维持英国经济和生活方式造成的相对风险。[61]2015年英国地质调查局風險列表,銻在相對供應風險指數中排名第二(僅次於稀土元素)。[62] 這指出它目前是對於英國經濟和生活方式具有經濟價值的化學元素或元素群的第二高供應風險。此外,在2014年發布的一份報告(修訂了2011年發布的初始報告)中,銻被確定為歐盟20種關鍵原材料之一。相對於其經濟重要性,銻保持著高供應風險,92%的銻是從中國進口的,此為一個極高的生產集中度。[63]

欧盟

[编辑]欧盟在2011年的一份报告中也将锑列为12种关键的原料之一,主要是因为来自中国以外的锑产量很少。[64]銻被認為是國防、汽車、建築和紡織品的重要原材料。 歐盟成員國境內沒有開採锑,因此是完全依賴進口,主要來自土耳其 (62%)、玻利維亞 (20%) 和危地馬拉 (7%)。[65]

美國

[编辑]銻被美國被認為是一種對經濟和國家安全至關重要的礦產商品。美國關鍵和戰略礦產供應鏈小組委員會(Subcommittee on Critical and Strategic Mineral Supply Chains)從1996年至2008年篩選了78種礦產資源,發現包括銻在內的一小部分礦物一直屬於潛在的關鍵礦物類別。在未來將對已發現的礦物子集進行第二次評估,以確定哪些礦產應該被定義為重大風險且對美國的利益至關重要。[66]從2011年到2014年,美國68%的銻來自中國,14%來自印度,4%來自墨西哥,14%來自其他地方,而目前沒有公開美國政府的庫存量。[67]截止2021年,美國本土並未開採任何銻。[68]

应用

[编辑]60%的锑用于生产阻燃剂,而20%的锑用于制造电池中的合金材料、滑动轴承和焊接剂。[9]

阻燃剂

[编辑]锑的最主要用途是它的氧化物三氧化二锑用于制造耐火材料。除了含卤素的聚合物阻燃剂以外,它几乎总是与卤化物阻燃剂一起使用。三氧化二锑形成锑的卤化物的过程可以减缓燃烧,即为它具有阻燃效应的原因。[69] 这些化合物与氢原子、氧原子和羟基自由基反应,最终使火熄灭。[70]商业中这些阻燃剂应用于儿童服装、玩具、飞机和汽车座套。它也用于玻璃纤维复合材料(俗称玻璃钢)工业中聚酯树脂的添加剂,例如轻型飞机的发动机盖。树脂遇火燃烧但火被扑灭后它的燃烧就会自行停止。[10][71]

合金

[编辑]锑能与铅形成用途广泛的合金,这种合金硬度与机械强度相比锑都有所提高。大部分使用铅的场合都加入数量不等的锑来制成合金。在铅酸电池中,这种添加剂改变电极性质,并能减少放电时副产物氢气的生成。[10][72]锑也用于减摩合金(例如巴比特合金),[73]子弹、铅弹、网线外套、铅字合金(例如Linotype排字机[74])、銲料(一些无铅焊接剂含有5%的锑)、[75]铅锡锑合金、[76]以及硬化制作管风琴的含锡较少的合金。

其他应用

[编辑]其他的锑几乎都用在下文所述的三个方面。[9]第一项应用是生产聚对苯二甲酸乙二酯的稳定剂和催化剂。[9]第二项应用则是去除玻璃中显微镜下可见的气泡的澄清剂,主要用途是制造电视屏幕;[11]这是因为锑离子与氧气接触后阻碍了气泡继续生成。[77]第三项应用则是颜料。[9]锑在半导体工业中的应用正不断发展,主要是在超高电导率的n-型硅晶圆中用作掺杂剂,[78]这种材料用于生产二极管、红外线探测器和霍尔效应元件。20世纪50年代,小珠装的铅锑合金用于给NPN型合金型双极型锗晶体管晶体管的发射极和集电极上的渗杂,但此法晶体管早已被淘汰了四十多年。[79]锑化铟是用于制作中红外探测仪的原材料。[80][81][82]

锑的生物学或医学应用很少。主要成分为锑的药品称作含锑药剂(antimonial),是一种催吐剂。[83]锑化合物也用作抗原虫剂。从1919年起,酒石酸锑钾(俗称吐酒石)曾用作治疗血吸虫病的药物。它后来逐渐被吡喹酮所取代。[84]锑及其化合物用于多种兽医药剂,例如安修马林(硫苹果酸锑锂)用作反刍动物的皮肤调节剂。[85]锑对角质化的组织有滋养和调节作用,至少对动物是如此。

含锑的药物也用作治疗家畜的利什曼病的选择之一,例如葡甲胺锑酸盐。可惜的是,它不仅治疗指数较低,而且难以进入一些利什曼原虫无鞭毛体所在的骨髓,也就无法治愈影响内脏的疾病。[86]金属锑制成的锑丸曾被當作药。但它被其他人从空气中摄入后会导致中毒。[87]

在一些安全火柴的火柴头中使用了三硫化二锑。[88][89]锑-124和铍一起用于中子源:锑-124释放出伽马射线,引发铍的光致蛻變。[90][91]这样释放出的中子平均能量为24 keV。[92]锑的硫化物已被证实可以稳定汽车刹车片材料的摩擦系数。[93]锑也用于制造子弹和子弹示踪剂。[94]这种元素也用于传统的装饰中,[95][96]例如刷漆和艺术玻璃工艺。20世纪30年代前曾用它作牙釉质的遮光剂,但是多次发生中毒后就不再使用了。[88][97]

防护

[编辑]锑和它的许多化合物有毒,作用机理为抑制酶的活性,这点与砷类似;与同族的砷和铋一样,三价锑的毒性要比五价锑大。[98] 但是,锑的毒性比砷低得多,这可能是砷与锑之间在摄取、新陈代谢和排泄过程中的巨大差别所造成的:如三价锑和五价锑在消化道的吸收最多为20%;五价锑在细胞中不能被定量地还原为三价(事实上在细胞中三价锑反而会被氧化成五价锑[99]);由于体内不能发生甲基化反应,五价锑的主要排泄途径是尿液。[100] 急性锑中毒的症状也与砷中毒相似,主要引起心脏毒性(表现为心肌炎),不过锑的心脏毒性还可能引起阿-斯综合征。有报告称,从搪瓷杯中溶解的锑等价于90毫克酒石酸锑钾时,锑中毒对人体只有短期影响;但是相当于6克酒石酸锑钾时,就会在三天后致人死亡。[96] 吸入锑灰也对人体有害,有时甚至是致命的:小剂量吸入时会引起头疼、眩晕和抑郁;大剂量摄入,例如长期皮肤接触可能引起皮肤炎、损害肝肾、剧烈而频繁的呕吐,甚至死亡。[101]

锑不能与强氧化剂、强酸、氢卤酸、氯或氟一起存放,并且应与热源隔绝。[102]

锑在浸取时会从聚对苯二甲酸乙二酯(PET)瓶中进入液体。[103]检测到的锑浓度标准则是瓶裝水低于饮用水,[104]英国生产的浓缩果汁(暂无标准)被检测到含锑44.7 µg/L,远远超出欧盟自来水的标准5 µg/L。[105][106]各个组织的标准分别是:

参见

[编辑]注释

[编辑]- ^ 原文:We only know of antimony at the present day as a highly brittle and crystalline metal, which could hardly be fashioned into a useful vase, and therefore this remarkable 'find' (artifact mentioned above) must represent the lost art of rendering antimony malleable.

- ^ 在1710年时戈特弗里德·莱布尼茨在认真调查过后认为前面的作品都是错误的,也没有名叫巴西利厄斯·华伦提努的修士。那本书的作者实际上是Johann Thölde(1565年—1624年)。历史专家现在同意此书为16世纪中叶所著,其作者很可能是Thölde。[36] 在这以后,Harold Jantz可能是唯一否认Thölde的原作者身份的现代学者,但他同意此书著于1550年之后,参见Catalogue of German Baroque literature。

参考资料

[编辑]- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 2022-05-04. ISSN 1365-3075. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603 (英语).

- ^ Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2012-01-12.archive, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 81st edition, CRC press.

- ^ 夏征农、陈至立 (编). 《辞海》第六版彩图本. 上海: 上海辞书出版社. 2009年: 第3227页. ISBN 9787532628599.

- ^ 銻. 萌典. [2016-08-12]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-06) (中文(臺灣)).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 SHORTLAND, A. J. APPLICATION OF LEAD ISOTOPE ANALYSIS TO A WIDE RANGE OF LATE BRONZE AGE EGYPTIAN MATERIALS. Archaeometry. 2006-11-01, 48 (4): 657–669. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2006.00279.x.

- ^ 成倩, 郭金龙. 古代西方玻璃制作中锑与锡的使用[C]// 全国第十届考古与文物保护化学学术研讨会. 中国化学会, 2008.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Native antimony. Mindat.org. (原始内容存档于2003-04-28).

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Peng, J.; Hu, R.-Z.; Burnard, P. G. Samarium–neodymium isotope systematics of hydrothermal calcites from the Xikuangshan antimony deposit (Hunan, China): the potential of calcite as a geochronometer. Chemical Geology. 2003, 200: 129. doi:10.1016/S0009-2541(03)00187-6.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Butterman, C.; Carlin, Jr., J.F. Mineral Commodity Profiles: Antimony (PDF). Unites States Geological Survey. 2003 [2012-07-23]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-11-04).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Sabina C. Grund, Kunibert Hanusch, Hans J. Breunig, Hans Uwe Wolf "Antimony and Antimony Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi: 10.1002/14356007.a03_055.pub2

- ^ 11.0 11.1 De Jong, Bernard H. W. S.; Beerkens, Ruud G. C.; Van Nijnatten, Peter A. Glass. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. 2000. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_365.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils and Holleman, Arnold Frederick. Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. 2001. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ^ 高惠章. 世界钱币史上的珍品:贵州当十锑币. 收藏界. 2004, (3) [2012-07-05]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-04).

- ^ Metals Used in Coins and Medals. ukcoinpics.co.uk. (原始内容存档于2010-12-26).

- ^ Robert Hare. A Compendium of the Course of Chemical Instruction in the Medical Department of the University of Pennsylvania 3. J.G. Auner. 1836: 401.

- ^ Ashcheulov, A. A.; Manyk, O. N.; Manyk, T. O.; Marenkin, S. F.; Bilynskiy-Slotylo, V. R. Some Aspects of the Chemical Bonding in Antimony. Inorganic Materials. 2013, 49 (8): 766–769. doi:10.1134/s0020168513070017.

- ^ Shen, Xueyang; Zhou, Yuxing; Zhang, Hanyi; Derlinger, Volker L.; Mazzarello, Riccardo; Zhang, Wei. Surface effects on the crystallization kinetics of amorphous antimony. Nanoscale. 2023, 15: 15259–15267. doi:10.1039/D3NR03536K.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Lide, D. R. (编). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 82nd. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 2001: 4-4. ISBN 0-8493-0482-2.

- ^ Krebs, H.; Schultze-Gebhardt, F.; Thees, R. Über die Struktur und die Eigenschaften der Halbmetalle. IX: Die Allotropie des Antimons. Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie. 1955, 282 (1–6): 177–195. doi:10.1002/zaac.19552820121 (德语).

- ^ 20.0 20.1 "Antimony" in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 5th ed. 2004. ISBN 978-0-471-48494-3

- ^ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Wang, Chung Wu. The Chemistry of Antimony. Antimony: Its History, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Geology, Metallurgy, Uses, Preparation, Analysis, Production and Valuation with Complete Bibliographies (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Charles Geiffin and Co. Ltd. 1919: 6–33 [2012-06-22]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-09-12).

- ^ Norman, Nicholas C. Chemistry of arsenic, antimony, and bismuth. 1998: 50–51. ISBN 978-0-7514-0389-3. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ Georges, Audi; Bersillon, O.; Blachot, J.; Wapstra, A.H. The NUBASE Evaluation of Nuclear and Decay Properties. Nuclear Physics A (Atomic Mass Data Center). 2003, 729: 3–128. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Carlin, Jr., James F. Mineral Commodity Summaries: Antimony (PDF). United States Geological Survey. [2012-01-23]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-01-31).

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edn.), Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-3365-9.

- ^ Daniel L. Reger; Scott R. Goode; David W. Ball. Chemistry: Principles and Practice 3rd. Cengage Learning. 2009: 883.

- ^ 27.0 27.1 James E. House. Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. 2008: 502.

- ^ 28.0 28.1 S. M. Godfrey; C. A. McAuliffe; A. G. Mackie; R. G. Pritchard. Nicholas C. Norman , 编. Chemistry of arsenic, antimony, and bismuth. Springer. 1998. ISBN 0-7514-0389-X.

- ^ Long, G. The oxidation number of antimony in antimony pentasulfide. Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry Letters. 1969, 5: 21. doi:10.1016/0020-1650(69)80231-X.

- ^ Lees, R; Powell, A; Chippindale, A. The synthesis and characterisation of four new antimony sulphides incorporating transition-metal complexes. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 2007, 68 (5–6): 1215. Bibcode:2007JPCS...68.1215L. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2006.12.010.

- ^ Antimony. PediaPress.

- ^ Louis Kahlenberg. Outlines of Chemistry – A Textbook for College Students. READ BOOKS. 2008: 324–325. ISBN 1-4097-6995-X.

- ^ Elschenbroich, C. "Organometallics" (2006) Wiley-VCH: Weinheim. ISBN 978-3-527-29390-2

- ^ Robert E. Tapscott; Ronald S. Sheinson; Valeri Babushok; Marc R. Nyden; Richard G. Gann. Alternative Fire Suppressant Chemicals: A Research Review with Recommendations (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology: 65. [2016-12-17]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2010-05-31).

- ^ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Moorey, P. R. S. Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: the Archaeological Evidence. New York: Clarendon Press. 1994: 241. ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- ^ Priesner, Claus and Figala, Karin (编). Alchemie. Lexikon einer hermetischen Wissenschaft. München: C.H. Beck. 1998 (德语).

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira. The discovery of the elements. II. Elements known to the alchemists. Journal of Chemical Education. 1932, 9: 11. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9...11W. doi:10.1021/ed009p11.

- ^ Dampier, William Cecil. A history of science and its relations with philosophy & religion. London: Cambridge U.P.: 73. 1961. ISBN 978-0-521-09366-8.

- ^ Mellor, Joseph William. Antimony. A comprehensive treatise on inorganic and theoretical chemistry. 1964: 339 [2012-07-03]. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ Klaproth, M. XL.Extracts from the third volume of the analyses. Philosophical Magazine Series 1. 1803, 17 (67): 230 [2012-07-03]. doi:10.1080/14786440308676406. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ 41.0 41.1 Online etymology dictionary. Choice Reviews Online. 2003-10-01, 41 (02): 41–0659–41–0659. ISSN 0009-4978. doi:10.5860/choice.41-0659.

- ^ Kroschwitz, Jacqueline I.; Seidel, Arza. Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology. 5th. Hoboken, N.J. ISBN 9780471484943. OCLC 53178503.

- ^ BENADON, FERNANDO; GIOIA, TED. How Hooker found his boogie: a rhythmic analysis of a classic groove. Popular Music. 2009-01, 28 (1): 19–32. ISSN 0261-1430. doi:10.1017/s0261143008001578.

- ^ Greenwood, Dara N.; Lippman, Julia R. Gender and Media: Content, Uses, and Impact. Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology. New York, NY: Springer New York. 2009-12-04: 643–669. ISBN 9781441914668.

- ^ Pouillaude, Frédéric. Writing That Says Nothing. Oxford Scholarship Online. 2017-06-22. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199314645.003.0009.

- ^ Mody, Ashoka. Schröder Asserts the German National Interest, 1999–2003. Oxford Scholarship Online. 2018-05-24. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199351381.003.0004.

- ^ FOOTE, THELMA WILLS. Introduction “The Angel Would Like to Stay, Awaken the Dead, and Make Whole What Has Been Smashed”. Black and White Manhattan. Oxford University Press. 2004-11-18: 3–20. ISBN 9780195165371.

- ^ Berzelius, Jöns Jakob. A view of the progress and present state of animal chemistry (translated from the Swedish by Gustavus Brunnmark). London: Printed by J. Skirven and sold by J. Hatchard, J. Johnson, and T. Boosey. 1813.

- ^ Sarton, George. (Al-morchid fi'l-kohhl) ou Le guide d'oculistique. Max Meyerhof. Isis. 1935-02, 22 (2): 539–542. ISSN 0021-1753. doi:10.1086/346926.

- ^ Albright, W. F. Notes on Egypto-Semitic Etymology. II. The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 1918-07, 34 (4): 215–255. ISSN 1062-0516. doi:10.1086/369866.

- ^ Celsus. Brill’s New Pauly Supplements I - Volume 2 : Dictionary of Greek and Latin Authors and Texts. [2019-09-28].

- ^ Antimony Statistics and Information (PDF). National Minerals Information Center. USGS. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-10-09).

- ^ Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability. European Commission. 2020 [2 February 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-20).

- ^ Nassar, Nedal T.; et al. Evaluating the mineral commodity supply risk of the U.S. manufacturing sector. Sci. Adv. 2020-02-21, 6 (8): eaay8647. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.8647N. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7035000

. PMID 32128413. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay8647.

. PMID 32128413. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay8647.

- ^ 55.0 55.1 Study of the Antimony market by Roskill Consulting Group (PDF). (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-10-18).

- ^ 56.0 56.1 Antimony Uses, Production and Prices Primer (PDF). (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-10-25).

- ^ 57.0 57.1 Norman, Nicholas C. Chemistry of arsenic, antimony, and bismuth. 1998: 45 [2012-07-23]. ISBN 978-0-7514-0389-3. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ Wilson, N.J.; Craw, D.; Hunter, K. Antimony distribution and environmental mobility at an historic antimony smelter site, New Zealand. Environmental Pollution. 2004, 129 (2): 257–66. PMID 14987811. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2003.10.014.

- ^ Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability. European Commission. 2020 [2 February 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-20).

- ^ Nassar, Nedal T.; et al. Evaluating the mineral commodity supply risk of the U.S. manufacturing sector. Sci. Adv. 2020-02-21, 6 (8): eaay8647. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.8647N. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7035000

. PMID 32128413. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay8647.

. PMID 32128413. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay8647.

- ^ British Geologocal Survey - Risk List. [2012-07-03]. (原始内容存档于2011-09-23).

- ^ List of Contributors. Coastal Risk Management in a Changing Climate. Elsevier. 2015: xiii–xxxi. ISBN 9780123973108.

- ^ Phosphate rock in EU list of 20 critical raw materials. Focus on Surfactants. 2015-02, 2015 (2): 4. ISSN 1351-4210. doi:10.1016/s1351-4210(15)30009-3.

- ^ Khrennikov, Ilya. Russian Antimony Miner for iPads Looks at IPO to Challenge China. 2012-03-05 [2012-07-03]. (原始内容存档于2012-05-08).

- ^ Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability. European Commission. 2020 [2 February 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-20).

- ^ General method to declare the use of critical raw materials in energy-related products. BSI British Standards.

- ^ Purcell, Arthur. Conference report. Resources Policy. 1978-06, 4 (2): 146. ISSN 0301-4207. doi:10.1016/0301-4207(78)90019-3.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2022. Antimony (PDF). [1 February 2022]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-10-09).

- ^ Weil, Edward D; Levchik, Sergei V. Antimony trioxide and Related Compounds. Flame retardants for plastics and textiles: Practical applications. 2009-06-04 [2012-07-23]. ISBN 978-3-446-41652-9. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ JW Hastie, Mass spectrometric studies of flame inhibition: Analysis of antimony trihalides in flames, Combustion and Flame, vol. 21, Aug 1973, pp49-54

- ^ Weil, Edward D; Levchik, Sergei V. Flame retardants for plastics and textiles: Practical applications. 2009-06-04: 15–16 [2012-07-23]. ISBN 978-3-446-41652-9. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ Kiehne, Heinz Albert. Types of Alloys. Battery technology handbook. CRC Press. 2003: 60–61. ISBN 978-0-8247-4249-2.

- ^ Williams, Robert S. Principles of Metallography. Read books. 2007: 46–47. ISBN 978-1-4067-4671-6.

- ^ Holmyard, E. J. Inorganic Chemistry – A Textbooks for Colleges and Schools. Read Books. 2008: 399–400. ISBN 978-1-4437-2253-7.

- ^ Ipser, H.; Flandorfer, H.; Luef, Ch.; Schmetterer, C.; Saeed, U. Thermodynamics and phase diagrams of lead-free solder materials. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics. 2007, 18 (1–3): 3–17. doi:10.1007/s10854-006-9009-3.

- ^ Hull, Charles. Pewter. Osprey Publishing. 1992: 1–5. ISBN 978-0-7478-0152-8.

- ^ Yamashita H. et al, Voltammetric Studies of Antimony Ions in Soda-lime-silica Glass Melts up to 1873 K, Analytical Sciences, Jan 2001, Vol. 17

- ^ O'Mara, William C.; Herring, Robert B.; Hunt, Lee Philip. Handbook of semiconductor silicon technology. William Andrew. 1990: 473. ISBN 978-0-8155-1237-0.

- ^ Maiti,, C. K. Selected Works of Professor Herbert Kroemer. World Scientific, 2008. 2008: 101. ISBN 978-981-270-901-1.

- ^ Committee On New Sensor Technologies: Materials And Applications, National Research Council (U.S.). Expanding the vision of sensor materials. 1995: 68 [2012-07-23]. ISBN 978-0-309-05175-0. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ Kinch, Michael A. Fundamentals of infrared detector materials. 2007: 35 [2012-07-23]. ISBN 978-0-8194-6731-7. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ Willardson, Robert K; Beer, Albert C. Infrared detectors. 1970: 15 [2012-07-23]. ISBN 978-0-12-752105-3. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ Russell, Colin A. Antimony's Curious History. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 2000, 54 (1): 115–116. JSTOR 532063. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2000.0101.

- ^ a., Harder. Chemotherapeutic approaches to schistosomes: Current knowledge and outlook. Parasitology Research. 2002, 88 (5): 395–7. PMID 12049454. doi:10.1007/s00436-001-0588-x.

- ^ Kassirsky, I. A; Plotnikov, N. N. Diseases of Warm Lands: A Clinical Manual. 2003-08-01: 262–265. ISBN 978-1-4102-0789-0.

- ^ Santé, Organisation Mondiale de la. Drugs used in parasitic diseases. 1995-10: 19–21 [2012-07-23]. ISBN 978-92-4-140104-3. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ McCallum, R. Ian. Antimony in medical history.. Edinburgh: Pentland. 1999. ISBN 1-85821-642-7.

- ^ 88.0 88.1 National Research Council. Trends in usage of antimony: report. National Academies. 1970: 50.

- ^ Stellman, Jeanne Mager; Office, International Labour. Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety: Chemical, industries and occupations. 1998: 109 [2012-07-23]. ISBN 978-92-2-109816-4. (原始内容存档于2019-07-10).

- ^ Lalovic, M. The energy distribution of antimonyberyllium photoneutrons. Journal of Nuclear Energy. 1970, 24 (3): 123. Bibcode:1970JNuE...24..123L. doi:10.1016/0022-3107(70)90058-4.

- ^ Ahmed, Syed Naeem. Physics and engineering of radiation detection. 2007-04-12: 51 [2012-07-23]. ISBN 978-0-12-045581-2. (原始内容存档于2015-02-22).

- ^ Schmitt, H. Determination of the energy of antimony-beryllium photoneutrons. Nuclear Physics. 1960, 20: 220. Bibcode:1960NucPh..20..220S. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(60)90171-1.

- ^ Jang, H and Kim, S. The effects of antimony trisulfide Sb S and zirconium silicate in the automotive brake friction material on friction. Journal of Wear. 2000.

- ^ Randich, Erik; Duerfeldt, Wayne; McLendon, Wade; Tobin, William. A metallurgical review of the interpretation of bullet lead compositional analysis. Forensic Science International. 2002, 127 (3): 174–91. PMID 12175947. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(02)00118-4.

- ^ Haq, I; Khan, C. Hazards of a traditional eye-cosmetic--SURMA. JPMA. the Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 1982, 32 (1): 7–8. PMID 6804665.

- ^ 96.0 96.1 McCallum, RI. President's address. Observations upon antimony. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1977, 70 (11): 756–63. PMC 1543508

. PMID 341167.

. PMID 341167.

- ^ Kaplan, Emanuel; Korff, Ferdinand A. Antimony in Food Poisoning. Journal of Food Science. 1936, 1 (6): 529. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1936.tb17817.x.

- ^ Winship, K. A. Toxicity of antimony and its compounds. Adverse drug reactions and acute poisoning reviews. 1987, 6 (2): 67–90. PMID 3307336.

- ^ Foster, S.; Maher, W.; Krikowa, F.; Telford, K.; Ellwood, M. Observations on the measurement of total antimony and antimony species in algae, plant and animal tissues. Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 2005, 7 (12): 1214–1219. PMID 16307074. doi:10.1039/b509202g.

- ^ Gebel, T. Arsenic and antimony: Comparative approach on mechanistic toxicology. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 1997, 107 (3): 131–44. PMID 9448748. doi:10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00087-2.

- ^ Sundar, S.; Chakravarty, J. Antimony Toxicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2010, 7 (12): 4267–4277. PMC 3037053

. PMID 21318007. doi:10.3390/ijerph7124267.

. PMID 21318007. doi:10.3390/ijerph7124267.

- ^ Antimony MSDS[永久失效連結]. Baker

- ^ Westerhoff, P; Prapaipong, P; Shock, E; Hillaireau, A. Antimony leaching from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic used for bottled drinking water. Water research. 2008, 42 (3): 551–6. PMID 17707454. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2007.07.048.

- ^ 104.0 104.1 Shotyk, W.; Krachler, M.; Chen, B. Contamination of Canadian and European bottled waters with antimony from PET containers. Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 2006, 8 (2): 288–92. PMID 16470261. doi:10.1039/b517844b.

- ^ Hansen, Claus; Tsirigotaki, Alexandra; Bak, Søren Alex; Pergantis, Spiros A.; Stürup, Stefan; Gammelgaard, Bente; Hansen, Helle Rüsz. Elevated antimony concentrations in commercial juices. Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 17 February 2010, 12 (4): 822–4. PMID 20383361. doi:10.1039/b926551a.

- ^ Borland, Sophie. Fruit juice cancer warning as scientists find harmful chemical in 16 drinks. Daily Mail. 1 March 2010. (原始内容存档于2012-10-23).

- ^ Wakayama, Hiroshi, "Revision of Drinking Water Standards in Japan" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (Japan), 2003; Table 2, p. 84

参考书目

[编辑]- (英文)Endlich, F. M. On Some Interesting Derivations of Mineral Names. The American Naturalist. 1888, 22 (253): 21–32 [28]. JSTOR 2451020. doi:10.1086/274630.

- (德文)埃德蒙·奥斯卡·冯·李普曼 (1919) Entstehung und Ausbreitung der Alchemie, teil 1. Berlin: Julius Springer.

- (英文)Public Health Statement for Antimony

外部链接

[编辑]- 元素锑在洛斯阿拉莫斯国家实验室的介紹(英文)

- EnvironmentalChemistry.com —— 锑(英文)

- 元素锑在The Periodic Table of Videos(諾丁漢大學)的介紹(英文)

- 元素锑在Peter van der Krogt elements site的介紹(英文)

- WebElements.com – 锑(英文)

- National Pollutant Inventory – Antimony and compounds,archive

- WebElements.com – Antimony (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Chemistry in its element podcast (MP3),来自英国皇家化学学会的化学世界:Antimony (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)