使用者:Hmgqzx/sandboxII

Template:古生物學

古生物學 or palaeontology (發音: /ˌpeɪlɪɒnˈtɒlədʒi/, /ˌpeɪlɪənˈtɒlədʒi/ or /ˌpælɪɒnˈtɒlədʒi/, /ˌpælɪənˈtɒlədʒi/) is the scientific study of 史前史的生命. It includes the study of 化石s to determine 生命體s' 演變 and interactions with each other and their environments (their 古生態學). As a "歷史學的 science" it attempts to explain 成因 rather than conduct experiments to observe effects. Paleontological observations have been documented as far back as the 5th century BC. The science became established in the 18th century as a result of 喬治·居維葉's work on 比較解剖學, and developed rapidly in the 19th century. The term itself originates from Greek: παλαιός (palaios) meaning "old, ancient," ὄν, ὀντ- (on, ont-), meaning "being, creature" and λόγος (logos), meaning "speech, thought, study".

f

古生物學處在生物學與地質學的交界處,和考古學的邊界更加是不易分辨。它現在廣泛運用了其他科學支系的技術,包括生物化學,數學以及工程學。藉由這些技術,古生物學家去發現更多關於生命的進化歷史的事情, almost all the way back to when 地球 became capable of supporting 生命, about 3,800百萬年前. 隨着知識增加, 古生物學已經發展出更加專業的子分類 , 有些人專注於研究生物體 化石,有人研究生態學和有關環境的歷史,如古氣候學。

f

實體化石 and 遺蹟化石 are 主要證據 about 古生命, and 地球化學的證據已幫助破譯 演變 of 生命 before 有足夠大的 生命體s to 留下化石s.

估計現存化石的時期是必要的,但也難以實現: 有時 相鄰的 地層允許使用放射性定年法, which provides absolute dates that are accurate to within 0.5%, 但更加經常的是古生物學家必須依靠 相對年齡測定 by 解決"拼圖" of 生物地層學.

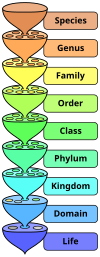

分類 古生命體也很困難, 因為許多生命體並不適用於生物分類法 that 普遍用來分類現在倖存的生命體, and 古生物學家 更加經常 使用 支序分類學 來 描繪出 演化的 "family trees".

(The final quarter of 20世紀)20世紀的前25年 見證了 分子系統發生學(Molecular phylogenetics)的發展, which 研究調查 生命體間的親緣關係 by 測量他們的基因組中的DNA的相似度。

分子系統發生學 現用來 估計 物種 diverged 的時期 , but 有爭議 about (這種估計所依賴的)分子鐘的可靠性。

Overview

最簡單的定義是"對古生命的研究".[1] 古生物學 尋找 幾個方面的信息 of 過去的生命體s: "他們的特性和起源,他們的 環境and 演變, and what they can tell us about the 地球's organic and inorganic 過去".[2]

A 歷史學的 science

古生物學是歷史科學之一, along with 考古學, 地質學, 生物學, 天文學, 宇宙學, 語言學 and 歷史學 它本身.[3] 這意味着它主要致力於 描述過去的現象 and 重現他們的成因.[4] 所以它主要有3個要素: 描述現象; 建立發展出統一的理論 about the 成因 of 各種類型的change; and 應用這些理論 to 特定事實.[3]

.

當試圖解釋過去的現象時, 古生物學家s and 其他的歷史學家一樣,通常是 建立 一連串假定 about the 成因 ,然後尋找確鑿證據, a piece of 證據 that 表明s that 其中的一個假定比其他的假定能解釋更好。有時 the 確鑿證據 被發現 by 幸運的意外 during 其他研究時. 例如,發現 by 路易斯·沃爾特·阿爾瓦雷茨(Luis Alvarez) and 沃爾特·阿爾瓦雷茨 of an 銥-rich layer at the 白堊紀–第三紀 boundary 讓 小行星撞擊 and 火山作用 成為 最受喜愛的(favored)解釋 for the 白堊紀-第三紀滅絕事件.[4]

f

另一種主要的科學形式-實驗科學,which is often said to work by 設計實驗s to 證明假定錯誤 about the workings and 成因 of 自然現象 – 注意 that 這種方法不能證明假定正確,因為往後可能有實驗證明它錯誤。 然而,當面對完全意想不到的現象時, 例如 the first 證據 for 看不見的輻射, 實驗科學家 通常使用相同的方法as 歷史學家: 建立一連串假定 about the 成因 and 然後尋找一個 "確鑿證據".[4]

Related sciences

f

古生物學 lies on the boundary between 生物學 and 地質學 since 古生物學 focuses on the record of past 生命 but its main source of 證據 is 化石s, which are found in rocks.[5] For 歷史學的 reasons 古生物學 is part of the 地質學 系s of many universities, 因為在19世紀和20世紀早期,地質學系發現了估計岩層年代的重要古生物學證據 while 生物學系s showed little interest.[6]

f

古生物學也與考古學有一些重疊, which 主要 works with objects made by humans and with human remains, while 古生物學家s 感興趣於 特性和演變 of 人類 as 生命體s. 當處理 證據 about 人類, 考古學家 and 古生物學家 可能會一起工作 – 例如, 古生物學家 might 識別 動物或植物的化石 around 考古遺址(遺蹟), to 發現 曾居住在此的人們吃了什麼; or 他們 might 分析當時的氣候 when 人類居住在此.[7]

f

另外, 古生物學也經常使用其他學科的方法技術, 包括 生物學, 生態學, 化學, 物理學 and 數學.[1] 例如, 地球化學的 特徵 from 岩石能 may 幫助 to 發現何時生命第一次出現 on 地球,[8] and 分析 of 碳 同位素比 能幫助 to 確定氣候 變化 and 甚至解釋 主要的 transitions ,像二疊紀-三疊紀滅絕事件.[9] 一個相對較近的學科, 分子系統發生學, 常用來 重建 演化的 "family trees" by 使用比較 of 不同現代生命體s' DNA and RNA ; 它現在也被用來 估計 日期 of 重大演化的發展, 儘管這種方法仍有爭議 because of 懷疑 about "分子鐘"的可靠性.[10] 工程學中的技術 現在也被用來分析 古生命體可能是如何 worked 的, 例如 暴龍能移動多快 and 它的咬力有多大.[11][12]

f

A 組合 of 古生物學, 生物學, and 考古學, 古神經病學(paleoneurology) is the study of 顱腔模型 of 物種s related to humans to 了解人類大腦的演變 . [13]

古生物學 甚至 對 太空生物學有貢獻, the 調查 of 可能存在的生命 on 其他行星, by 發展模型 of 生命如何出現 and by 提供技術方法 for 檢測生命存在的證據 .[14]

Subdivisions

As knowledge has increased, 古生物學 has developed specialised subdivisions.[15] 古脊椎動物學 concentrates on 化石s of 脊椎動物, from the earliest 魚類 to the immediate ancestors of modern 哺乳動物s. 古無脊椎動物學 deals with 化石s of 無脊椎動物s such as molluscs, arthropods, annelid worms and 棘皮動物s. 古植物學 focuses on the study of 化石 plants, but traditionally includes the study of 化石 algae and fungi. 孢粉學, the study of pollen and spores produced by land plants and protists, straddles the border between 古生物學 and botany, as it deals with both living and 化石 生命體s. Micro古生物學 deals with all microscopic 化石 生命體s, regardless of the group to which they belong.[16]

.

Instead of focusing on individual 生命體s, 古生態學 examines the interactions between different 生命體s, such as their places in 食物鏈s, and the two-way interaction between 生命體s and their environment[17] – for example the development of oxygenic photosynthesis by 細菌 hugely increased the productivity and diversity of ecosystems,[18] and also caused the oxygenation of the atmosphere, which in turn was a prerequisite for the 演變 of the most complex eucaryotic cells, from which all 多細胞 的生命體s are built.[19] 古氣候學, although sometimes treated as part of 古生態學,[16] focuses more on the history of 地球's climate and the mechanisms that have changed it[20] – which have sometimes included 演變ary developments, for example the rapid expansion of land plants in the 泥盆紀 period removed more 二氧化碳 from the atmosphere, reducing the 溫室效應 and thus helping to cause an 冰河時代 in the 石炭紀的 period.[21]

生物地層學, the use of 化石s to work out the chronological order in which rocks were formed, is useful to both 古生物學家s and geologists.[22] Biogeography studies the spatial distribution of 生命體s, and is also linked to 地質學, which explains how 地球's geography has changed over time.[23]

Sources of 證據

Body 化石s

化石s of 生命體s' 遺體 通常是最有益的證據類型. 最常見的類型是 木材, 骨頭, and 貝殼.[24] 化石isation is a rare event, and most 化石s 被破壞 by 侵蝕 or 變質作用 before 他們能被 observed. Hence the 化石 record is very incomplete, increasingly so further back in time. Despite this, it is often adequate to illustrate the broader patterns of 生命's history.[25] There are also biases in the 化石 record: different environments are more favorable to the preservation of different types of 生命體 or parts of 生命體s.[26] Further, only the parts of 生命體s that were already 礦化的(mineralised) are usually preserved, such as the shells of molluscs. Since most 動物 物種s are soft-bodied, they decay before they can become 化石ised. As a result, although there are 30-plus phyla of living 動物s, two-thirds have never been found as 化石s.[27]

.

Occasionally, unusual environments may preserve soft tissues. These lagerstätten allow 古生物學家s to examine the internal anatomy of 動物s that in other 沉積(沉澱物)s are represented only by shells, spines, claws, etc. – if they are preserved at all. However, even lagerstätten present an incomplete picture of 生命 at the time. The majority of 生命體s living at the time are probably not represented because lagerstätten are restricted to a narrow range of environments, e.g. where soft-bodied 生命體s can be preserved very quickly by events such as mudslides; and the exceptional events that cause quick burial make it difficult to study the normal environments of the 動物s.[28] The sparseness of the 化石 record means that 生命體s are expected to exist long before and after they are found in the 化石 record – this is known as the Signor-Lipps effect.[29]

遺蹟化石s

遺蹟化石s consist 主要 of 遺蹟 and 洞穴, 也包括 糞化石s (化石 排泄物) and 進食後留下的痕跡.[24][30] 遺蹟化石s are 特別有意義 because they represent a data source that is not limited to 動物s with easily 化石ized hard parts, and 他們反映了 生命體的行為習慣。 Also many traces date from significantly earlier than the body 化石s of 動物s that are thought to have been capable of making them.[31] 然而 精確分配 of 遺蹟化石s to 他們的製造者 is 通常不可能, 但 遺蹟 可能 for example 提供最早的物理證據 of the 外觀 of (moderately)中度複雜的動物 (comparable to 地球worms).[30]

地球化學的 observations

f

地球化學的 觀察結果 也許能幫助 to 推論 全球生物活性層次(the global level of biological activity), or the affinity of a certain 化石. For example 地球化學的 features of rocks 可能 揭露 生命 何時第一次出現在地球上,[8] and 可能提供 證據 of 真核細胞的 presence, 所有的多細胞生命體由此發展而來.[32] 分析 of 碳 同位素比 也許能幫助解釋 主要的 transitions ,像二疊紀-三疊紀滅絕事件.[9]

分類ing 古生命體s

.

Warm-bloodedness evolved somewhere in the

合弓綱–哺乳動物 transition.

? Warm-bloodedness must also have evolved at one of

these points – an example of convergent 演變.[33]

f

命名 groups of 生命體s in a way (that 清晰且廣泛同意) is 重要的, 因為引起古生物學的一些爭論僅是因為名字上的誤解。[34] 生物分類法 通常用來 分類 現在倖存的生命體s, but 陷入困難 when 處理 新發現的 生命體s that are 有顯着性差異 from 已知物種.例如: 很難決定 at what level to place a new higher-level grouping, e.g. 屬 or family or order;這是重要的,因為 the Linnean rules for naming groups 與 their levels 相關聯, and 因此如果一個 group 移動到一個不同的 level,它必須重新命名.[35]

.

古生物學家通常也使用支序分類學的方法, a 技術方法 for working out the 演化的 "family tree" of a set of 生命體s.[34] It works by the logic that, if groups B and C have more similarities to each other than either has to group A, then B and C are more closely related to each other than either is to A. Characters that are compared may be anatomical, such as the presence of a 脊索, or 分子, by comparing sequences of DNA or 蛋白質s. The result of a successful analysis is a hierarchy of clades – groups that share a common ancestor. Ideally the "family tree" has only two branches leading from each node ("junction"), but sometimes there is too little information to achieve this and 古生物學家s have to make do with junctions that have several branches. The cladistic technique is sometimes fallible, as some features, such as wings or camera eyes, evolved more than once, convergently – this must be taken into account in analyses.[33]

f

演化發展生物學, 通常縮寫為 "Evo Devo", 也能幫助古生物學家 to produce "family trees". 例如 the 胚胎學的 development of 一些現代腕足動物 顯示腕足動物也許是 the halkieriid的後代, which已在寒武紀時期滅絕。[36]

Estimating the dates of 生命體s

.

古生物學 seeks to map out how living things have changed through time. A substantial hurdle to this aim is the difficulty of working out how old 化石s are. Beds that preserve 化石s typically lack the radioactive elements needed for 放射性定年法. This technique is our only means of giving rocks greater than about 50 million years old an absolute age, and can be accurate to within 0.5% or better.[37] Although 放射性定年法 requires very careful laboratory work, its basic principle is simple: the rates at which various radioactive elements decay are known, and so the ratio of the radioactive element to the element into which it decays shows how long ago the radioactive element was incorporated into the rock. Radioactive elements are common only in rocks with a volcanic origin, and so the only 化石-bearing rocks that can be dated radiometrically are a few volcanic ash layers.[37]

.

Consequently, 古生物學家s must usually rely on 地層學 to date 化石s. 地層學 is the science of deciphering the "layer-cake" that is the 沉積(沉澱物)ary record, and has been compared to a 七巧板.[38] Rocks normally form relatively horizontal layers, with each layer younger than the one underneath it. If a 化石 is found between two layers whose ages are known, the 化石's age must lie between the two known ages.[39] Because rock sequences are not continuous, but may be broken up by faults or periods of 侵蝕, it is very difficult to match up rock beds that are not directly next to one another. However, 化石s of 物種s that survived for a relatively short time can be used to link up isolated rocks: this technique is called 生物地層學. For instance, the conodont Eoplacognathus pseudoplanus has a short range in the Middle Ordovician period.[40] If rocks of unknown age are found to have traces of E. pseudoplanus, they must have a mid-Ordovician age. Such index 化石s must be distinctive, be globally distributed and have a short time range to be useful. However, misleading results are produced if the index 化石s turn out to have longer 化石 ranges than first thought.[41] 地層學 and 生物地層學 can in general provide only relative dating (A was before B), which is often sufficient for studying 演變. However, this is difficult for some time periods, because of the problems involved in matching up rocks of the same age across different 大陸s.[42]

f

Family-tree 關係也許能幫助 減少 譜系(lineages)首次出現時的 日期. 例如, 如果B或C的化石在 X million years ago, and 計算出來的 "family tree" 說 A 是 B and C的祖先之一, 那麼 A 在X million years ago更早之前就已演變完成(then A must have evolved)。

f

也有可能估計 多久之前 兩個現存的演化支就已 diverged – 例如,它們最後的共同祖先大約多久前肯定還存在 – by 假設 that DNA 突變以恆定速率累積. These "分子鐘s", 然而, 是不可靠的, and 只提供非常粗略的時間: 例如,它們沒能足夠精確和可靠地去估計 在何時 the groups that feature in the 寒武紀大爆發 first evolved,[43] and (?)-不同技術中也許會因為某個因素變化,令估計結果不同(produced by different techniques may vary by a factor of two)[10]

Overview of the history of 生命

f

生命的演化歷史可以追溯到比3,000百萬年前更早, 可能遠至3,800百萬年前. 地球在大約4,570百萬年前形成 and, after a collision that 月球 在大約40 million years later形成, 也許在約4,440百萬年前能冷卻得足夠快以形成大氣層和海洋.[44] 然而有證據顯示月球 from 4,000 to 3,800 百萬年前有一個後期重轟炸期. 如果, as seem likely, 當時在地球也有這樣的轟炸, 首次出現的大氣層和海洋也許會被剝奪掉。[45] 最早的 明確的 關於地球上的生命 的證據 dates to 3,000百萬年前,( 儘管已經reports, 但仍常有爭議), 3,400百萬年前的細菌化石 和 地球化學中關於生命出現的證據 。3,800百萬年前.[8][46] 一些科學家提議 that 地球上的生命是從其他地方播種而來,[47] 但大多數研究集中在 各種解釋 of 生命如何能在地球上自然出現.[48]

The image shows the location, in the Burgsvik beds of 瑞典, where the texture was first identified as 證據 of a 微生物席.[49]

.

For about 2,000 million years 微生物席s, multi-layered colonies of different types of 細菌, were the 統治地位的 生命 on 地球.[50] The 演變 of oxygenic photosynthesis enabled them to play the major role in the oxygenation of the atmosphere[51] from about 2,400百萬年前. This change in the atmosphere increased their effectiveness as nurseries of 演變.[52] While 真核細胞s, cells with complex internal structures, may have been present earlier, their 演變 speeded up when they acquired the ability to transform oxygen from a 毒物 to a powerful source of energy in their 新陳代謝. This innovation may have come from primitive 真核細胞s capturing oxygen-powered 細菌 as 內共生體s and transforming them into 細胞器s called mitochondria.[53] The earliest 證據 of complex 真核細胞s with 細胞器s such as mitochondria, dates from 1,850百萬年前.[19]

f

多細胞生命只由真核細胞組成 , and the 最早的證據 for it 是[弗朗斯維爾化石群]](Francevillian Group Fossil) from 2,100百萬年前,[54] 儘管 細胞分化 for 不同功能 第一次出現在 between 1,430百萬年前 (一種可能的真菌) and 1,200百萬年前 (一種相當可能的 紅藻). 有性生殖 may be 細胞分化的先決條件之一, 因為一個無性生殖的多細胞生命體 might be 處於危險 of 被占據 by 無賴細胞(rogue cells) that 保持再生能力.[55][56]

.

已知的最早的動物 are 刺細胞動物ns from about 580百萬年前, but these are so modern-looking that the earliest 動物s must have appeared before then.[57] 早期的動物化石很稀少,因為它們沒有 develop mineralized hard parts that 化石ize easily until 約548百萬年前.[58] 最早的 modern-looking 兩側對稱動物n 動物s 出現在寒武紀早期, along with several "weird wonders" that bear little obvious resemblance to any modern 動物s. There is a long-running debate about whether this 寒武紀大爆發 was truly a very rapid period of 演化的 experimentation; alternative views are that modern-looking 動物s began evolving earlier but 化石s of their precursors have not yet been found, or that the "weird wonders" are 演化的 "aunts" and "cousins" of modern groups.[59] 脊椎動物 remained an obscure group until 第一條有頜的魚在奧陶紀後期出現。[60][61]

.

生命從水生到陸生 需要 生命體s to 解決數個問題, 包括對drying out的防護 and 支持他們自身對抗重力。[62][63][64](?)-最早的證據 of 陸生植物and 陸生無脊椎動物 大約從476百萬年前到490百萬年前開始各自出現.[63][65] The lineage that produced 陸生脊椎動物 evolved later but very rapidly( between370百萬年前 and 360百萬年前);[66] recent discoveries have overturned earlier ideas about the history and driving forces behind their 演變.[67] 陸生植物 were 如此成功 that 以至於他們造成了一場 生態危機 in 泥盆紀後期, until the 演變 and spread of fungi that could digest dead wood.[21]

f

在二疊紀時期合弓綱,包括哺乳動物的祖先,可能已經統治支配了陸地環境,[70]但二疊紀-三疊紀滅絕事件 251百萬年前 到來 very close to 擦掉 複雜的生命.[71] 這場滅絕顯然非常突然,至少對於脊椎動物來說。[72] 在從這場災難緩慢恢復的過程中, a previously obscure group, 古蜥s, became 最豐富和多樣化的陸生脊椎動物. One 古蜥 group,恐龍, were 統治地位的陸生脊椎動物 for the rest of the 中生代,[73] and 鳥類 進化出來 from one group of 恐龍.[69] 這一時期倖存的哺乳動物的祖先只有小的、主要在夜間活動的食蟲動物, but this apparent set-back may have accelerated the development of 哺乳動物ian traits such as 溫血性 and 毛髮.[74] (65百萬年前)白堊紀-第三紀滅絕事件之後, 殺掉非鳥類的恐龍s – 鳥類是唯一僅存的恐龍s – 哺乳動物 迅速增長 in 大小和多樣性,and(?)-一些接管了天空和海洋。[some took to the air and the sea].[75][76][77]

f

化石 證據 表明s that 開花植物s 出現 and 迅速多樣化 in白堊紀早期, between 130百萬年前 and 90百萬年前.[78] 它們迅速增加,統治了陸地生態系統,被認為是與傳粉昆蟲的共同演變推動所致。[79] 社會性昆蟲在大約相同的時期出現 and, 儘管它們的數量在 昆蟲"family tree" 占很小一部分, 但現在在整個昆蟲群中的構成了超過50%.[80]

.

Humans evolved from a lineage of upright-walking 猿s whose earliest 化石s date from over 6百萬年前.[81] Although early members of this lineage had 黑猩猩-sized 腦s, about 25% as big as modern humans', there are signs of a steady increase in 腦 size after about 3百萬年前.[82] There is a long-running debate about whether modern humans are descendants of a single small population in Africa, which then migrated all over the world less than 200,000 years ago and replaced previous 有人類特徵的 物種s, or arose worldwide at the same time as a result of 雜種繁殖.[83]

生物集群滅絕

至少從542百萬年前開始,地球上的生命就已遭受過偶然發生的生物集群滅絕。儘管這是當時的災難,但生物集群滅絕有時能加速地球上的生命的演化。 When dominance of particular 生態位s passes from one group of 生命體s to another, it is rarely because the new 統治地位的 group is "superior" to the old and 通常是因為一場滅絕事件消除了占統治地位的 the old group and 為new one 辟開了新道路。[84][85]

f

化石記錄似乎顯示滅絕的速度正在緩慢下來, with both 生物集群滅絕間的距離越來越長 and the average and background rates of 滅絕 正在減少。 然而並不確定真正的滅絕速度已經改變,因為這兩個觀察結果能以如下幾個方式解釋:[86]

.

- The oceans may have become more hospitable to 生命 over the last 500 million years and less vulnerable to 生物集群滅絕: 溶解氧 became more widespread and penetrated to greater depths; the development of 生命 on land reduced the run-off of nutrients and hence the risk of 富營養化 and 缺氧事件s; marine ecosystems became more diversified so that 食物鏈s were less likely to be disrupted.

f

- Reasonably 完整的化石非常稀少,大多數滅絕的生命體 are represented only by 局部化石s, and 在最老的岩層中,完整的化石是最少的。所以古生物學家肯定會錯誤地分配一些相同生命體的不同部分到不同的genera, ?[為了容納這些發現,通常單獨定義出一個genera]。 – 奇蝦的故事可以作為一個例子。

.

The risk of this mistake is higher for older 化石s because these are often unlike parts of any living 生命體. Many "superfluous" genera are represented by fragments that are not found again, and these "superfluous" genera appear to become extinct very quickly.[86]

f

化石記錄中的生物多樣性, which is

- "the number of distinct genera alive at any given time; that is, those whose first occurrence predates and whose last occurrence postdates that time"[90]

顯示了一個不同的趨勢: a 相當迅速的增加 from 542 to 400 百萬年前, a 輕微的下降 from 400 to 200 百萬年前(其中滅絕性的二疊紀-三疊紀滅絕事件 是重要因素之一), and a 迅速的增加 從200百萬年前至今.[90]

History of 古生物學

f

儘管 古生物學在大約1800年建立, 更早時已有思想家注意到了關於化石記錄的方面。 古希臘哲學家 色諾芬尼 (570–480 BC)從?[ 化石 sea shells] 總結出:陸地的一些區域曾經在水下.[91] 到了中世紀,波斯博物學家 伊本·西那,討論了化石s and 提議 a 理論 of 石化液(petrifying fluids) (Albert of Saxony (philosopher)在14世紀將其詳盡)。[92] 中國博物學家 沈括 (1031–1095) 提出 a 理論 of 氣候變化 ,根據某地區石化竹子的存在,因為在他的時代,那個地區對竹子來說太乾燥了。.[93]

f

In 近代史, 作為啟蒙時代自然哲學中一個不可分割的改變部分,對化石的系統研究出現了。在18世紀末期,喬治·居維葉's work 建立了比較解剖學 as 一個科學學科 and, by 證明一些形成化石的動物沒有倖存的動物與之相似, 論證 that 這些動物可能滅絕,引導了古生物學的萌芽.[94]關於化石記錄的知識擴展也在地質學的發展中扮演了越來越重要的角色, 特別是在地層學.[95]

f

19世紀上半葉,地質學和古生物學的活動日益好了起來,地質學協會和博物館的增加[96][97] 以及專業的地質學家和化石專家人數的增加.非純粹科學的原因也使得興趣增加,因為地質學和古生物學幫助實業家去發現和開採自然資源 例如煤.[98]

f

這(活動和專家)使得,關於地球生命歷史的知識急速增加 and 使對地質年代的定義有所進展, 主要依據化石證據. In 1822 Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blanville,Journal de Phisique的編輯, 創造了單詞"palaeontology"(古生物學) to 指代 the 通過化石對古代生活的生命體進行的研究。[99] 隨着關於生命歷史的知識繼續增加, it became日益明顯的 that 有一些連序系列(successive order) to 生命的發展過程. ?-This 推動發展了(encouraged) 早期的演化理論 on the 物種變遷論(Transmutation of species).[100] 在1859年查爾斯·達爾文出版物種起源後 , 許多古生物學的注意點轉移至理解演變的途徑(path), 包括人類演變, and 演化的理論.[100]

.

The last half of the 19th century saw a tremendous expansion in paleontological activity, especially in 北美洲.[102] The trend continued in the 20th century with additional regions of the 地球 being opened to systematic 化石 collection. 化石s found in China near the end of the 20th century have been particularly important as they have provided new information about the earliest 演變 of 動物s, early 魚類, 恐龍s and the 演變 of 鳥類s.[103]

.

The last few decades of the 20th century saw a renewed interest in mass 灭绝s and their role in the 演变 of 生命 on 地球.[104] There was also a renewed interest in the 寒武纪大爆发 that apparently saw the development of the body plans of most 动物 phyla. The discovery of 化石s of the Ediacaran biota and developments in paleo生物学 extended knowledge about the history of 生命 back far before the 寒武纪.[59]

.

Increasing awareness of Gregor Mendel's pioneering work in genetics led first to the development of population genetics and then in the mid-20th century to the modern 演化的 synthesis, which explains 演變 as the outcome of events such as 突變s and horizontal gene transfer, which provide genetic variation, with genetic drift and 自然選擇 driving changes in this variation over time.[105] Within the next few years the role and operation of DNA in genetic inheritance were discovered, leading to what is now known as the "Central Dogma" of molecular 生物學.[106] In the 1960s 分子系統發生學, the investigation of 演化的 "family trees" by techniques derived from 生物化學, began to make an impact, particularly when it was proposed that the human lineage had diverged from 猿s much more recently than was generally thought at the time.[107] Although this early study compared 蛋白質s from 猿s and humans, most 分子系統發生學 research is now based on comparisons of RNA and DNA.[108]

See also

- 化石 collecting

- List of 化石 sites (with link directory)

- List of notable 化石s

- List of transitional 化石s

- 放射性定年法

- Taxonomy of commonly 化石ised in脊椎動物

- Treatise on 無脊椎動物 古生物學

Notes

External links

- Smithsonian's Paleo生物學 website

- University of California Museum of 古生物學 FAQ About 古生物學

- The Paleontological Society

- The Palaeontological Association

- The 古生物學 Portal

Template:生物學-footer Template:Good article 僅在優良條目中使用!

- ^ 1.0 1.1 Cowen, R. History of 生命 3rd. Blackwell Science. 2000: xi. ISBN 0-632-04444-6.

- ^ Laporte, L.F. What, after All, Is 古生物学?. PALAIOS. 1988, 3 (5): 453. JSTOR 3514718. doi:10.2307/3514718. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ 3.0 3.1 Laudan, R. What's so Special about the Past?. Nitecki, M.H., and Nitecki, D.V. (編). History and 演变. SUNY Press. 1992: 58 [7 February 2010]. ISBN 0-7914-1211-3.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cleland, C.E. Methodological and Epistemic Differences between 历史学的 Science and 实验al Science (PDF). Philosophy of Science. 2002, 69 (3): 474–496 [September 17, 2008]. doi:10.1086/342453. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology. McGraw-Hill. 2002: 58. ISBN 0-07-913665-6.

- ^ Laudan, R. What's so Special about the Past?. Nitecki, M.H., and Nitecki, D.V. (編). History and 演变. SUNY Press. 1992: 57. ISBN 0-7914-1211-3.

- ^ How does 古生物学 differ from anthropology and 考古学?. University of California Museum of 古生物學. [September 17, 2008].

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Brasier, M., McLoughlin, N., Green, O., and Wacey, D. A fresh look at the 化石 证据 for early Archaean cellular 生命 (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: 生物學. 2006, 361 (1470): 887–902 [August 30, 2008]. PMC 1578727

. PMID 16754605. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1835. 已忽略未知參數

. PMID 16754605. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1835. 已忽略未知參數|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ 9.0 9.1 Twitchett RJ, Looy CV, Morante R, Visscher H, Wignall PB. Rapid and synchronous collapse of marine and terrestrial ecosystems during the end-二叠纪 biotic crisis. 地質學. 2001, 29 (4): 351–354. Bibcode:2001Geo....29..351T. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0351:RASCOM>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Peterson, Kevin J., and Butterfield, N.J. Origin of the Eumetazoa: Testing ecological predictions of 分子钟s against the Proterozoic 化石 record. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005, 102 (27): 9547–52. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.9547P. PMC 1172262

. PMID 15983372. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503660102.

. PMID 15983372. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503660102.

- ^ Hutchinson, John R.; Garcia, M. 暴龙 was not a fast runner. Nature. 28 February 2002, 415 (6875): 1018–1021. PMID 11875567. doi:10.1038/4151018a. Summary in press release No Olympian: Analysis hints T. rex ran slowly, if at all

- ^ Meers, M.B. Maximum bite force and prey size of 暴龙 rex and their relationships to the inference of feeding behavior. 歷史學的 生物學: A Journal of Paleo生物學. 2003, 16 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/0891296021000050755. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Bruner, Emiliano. Geometric morphometrics and palaeoneurology: 脑 sh猿 演变 in the 属 Homo. Journal of Human 演變. 2004, 47 (5): 279–303 [27 September 2011]. PMID 15530349. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.03.009. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Cady, S.L. 太空生物学: A New Frontier for 21st Century 古生物学家s. PALAIOS. 1998, 13 (2): 95–97. JSTOR 3515482. PMID 11542813. doi:10.2307/3515482. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Plotnick, R.E. A Somewhat Fuzzy Snapshot of Employment in 古生物学 in the United States. Palaeontologia Electronica (Coquina Press). [September 17, 2008]. ISSN 1094-8074.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 What is 古生物学?. University of California Museum of 古生物學. [September 17, 2008].

- ^ Kitchell, J.A. 演化的 Paleocology: Recent Contributions to 演化的 Theory. Paleo生物學. 1985, 11 (1): 91–104 [September 17, 2008].

- ^ Hoehler, T.M., Bebout, B.M., and Des Marais, D.J. The role of 微生物席s in the production of reduced gases on the early 地球. Nature. 19 July 2001, 412 (6844): 324–327 [July 14, 2008]. PMID 11460161. doi:10.1038/35085554.

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Hedges, S.B., Blair, J.E, Venturi, M.L., and Shoe, J.L. A molecular timescale of 真核细胞 演变 and the rise of complex 多细胞的 生命. BMC 演化的 生物學. 2004, 4: 2 [July 14, 2008]. PMC 341452

. PMID 15005799. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-2. 已忽略未知參數

. PMID 15005799. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-2. 已忽略未知參數|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ 古气候学. Ohio State University. [September 17, 2008].

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Algeo, T.J., and Scheckler, S.E. Terrestrial-marine teleconnections in the 泥盆纪: links between the 演变 of land plants, weathering processes, and marine 缺氧事件s. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: 生物學. 1998, 353 (1365): 113–130. PMC 1692181

. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0195.

. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0195.

- ^ 生物地层学: William Smith 請檢查

|url=值 (幫助). [September 17, 2008]. - ^ Biogeography: Wallace and Wegener (1 of 2) 請檢查

|url=值 (幫助). University of California Museum of 古生物學 and University of California at Berkeley. [September 17, 2008]. - ^ 24.0 24.1 What is 古生物学?. University of California Museum of 古生物學. [September 17, 2008].

- ^ Benton MJ, Wills MA, Hitchin R. Quality of the 化石 record through time. Nature. 2000, 403 (6769): 534–7. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..534B. PMID 10676959. doi:10.1038/35000558.

- Non-technical summary

- ^ Butterfield, N.J. Exceptional 化石 Preservation and the 寒武纪大爆发. Integrative and Comparative 生物學. 2003, 43 (1): 166–177 [June 28, 2008]. PMID 21680421. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.166.

- ^ Cowen, R. History of 生命 3rd. Blackwell Science. 2000: 61. ISBN 0-632-04444-6.

- ^ Butterfield, N.J. 生态学 and 演变 of 寒武纪 plankton (PDF). The 生態學 of the 寒武紀 輻射 (New York: Columbia University Press). 2001: 200–216 [September 27, 2007].

- ^ Signor, P.W. Sampling bias, gradual 灭绝 patterns and catastrophes in the 化石 record. Geological implications of impacts of large asteroids and comets on the 地球 (Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America). 1982: 291–296 [January 1, 2008]. A 84–25651 10–42.

- ^ 30.0 30.1 Fedonkin, M.A., Gehling, J.G., Grey, K., Narbonne, G.M., Vickers-Rich, P. The Rise of 动物s: 演变 and Diversification of the Kingdom 动物ia. JHU Press. 2007: 213–216 [November 14, 2008]. ISBN 0-8018-8679-1.

- ^ e.g. Seilacher, A. How valid is Cruziana 地层学? (PDF). International Journal of 地球 Sciences. 1994, 83 (4): 752–758 [September 9, 2007]. Bibcode:1994GeoRu..83..752S. doi:10.1007/BF00251073.

- ^ Brocks, J.J., Logan, G.A., Buick, R., and Summons, R.E. Archaean molecular 化石s and the rise of 真核细胞s. Science. 1999, 285 (5430): 1033–1036 [September 2, 2008]. PMID 10446042. doi:10.1126/science.285.5430.1033.

- ^ 33.0 33.1 Cowen, R. History of 生命 3rd. Blackwell Science. 2000: 47–50. ISBN 0-632-04444-6.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Brochu, C.A, and Sumrall, C.D. Phylogenetic Nomenclature and 古生物学. Journal of 古生物學. 2001, 75 (4): 754–757. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1306999. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2001)075<0754:PNAP>2.0.CO;2. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Ereshefsky, M. The Poverty of the Linnaean Hierarchy: A Philosophical Study of Biological Taxonomy. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 5. ISBN 0-521-78170-1.

- ^ Cohen, B. L. and Holmer, L. E. and Luter, C. The 腕足动物 fold: a neglected body plan hypothesis (PDF). Palaeontology. 2003, 46 (1): 59–65 [August 7, 2008]. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00287.

- ^ 37.0 37.1 Martin, M.W.; Grazhdankin, D.V.; Bowring, S.A.; Evans, D.A.D.; Fedonkin, M.A.; Kirschvink, J.L. Age of Neoproterozoic 两侧对称动物n Body and 遗迹化石s, White Sea, Russia: Implications for Metazoan 演变. Science (abstract). May 5, 2000, 288 (5467): 841–5. Bibcode:2000Sci...288..841M. PMID 10797002. doi:10.1126/science.288.5467.841.

- ^ Pufahl, P.K., Grimm, K.A., Abed, A.M., and Sadaqah, R.M.Y. Upper 白垩纪 (Campanian) phosphorites in Jordan: implications for the formation of a south Tethyan phosphorite giant. 沉積(沉澱物)ary 地質學. 2003, 161 (3–4): 175–205. Bibcode:2003SedG..161..175P. doi:10.1016/S0037-0738(03)00070-8. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Geologic Time: Radiometric Time Scale. U.S. Geological Survey. [September 20, 2008].

- ^ Löfgren, A. The conodont fauna in the Middle Ordovician Eoplacognathus pseudoplanus Zone of Baltoscandia. Geological Magazine. 2004, 141 (4): 505–524 [November 17, 2008]. doi:10.1017/S0016756804009227.

- ^ Gehling, James; Jensen, Sören; Droser, Mary; Myrow, Paul; Narbonne, Guy. Burrowing below the basal 寒武纪 GSSP, Fortune Head, Newfoundland. Geological Magazine. 2001, 138 (2): 213–218 [November 17, 2008]. doi:10.1017/S001675680100509X. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ e.g. Gehling, James; Jensen, Sören; Droser, Mary; Myrow, Paul; Narbonne, Guy. Burrowing below the basal 寒武纪 GSSP, Fortune Head, Newfoundland. Geological Magazine. 2001, 138 (2): 213–218 [November 17, 2008]. doi:10.1017/S001675680100509X. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Hug, L.A., and Roger, A.J. The Impact of 化石s and Taxon Sampling on Ancient Molecular Dating Analyses. Molecular 生物學 and 演變. 2007, 24 (8): 889–1897. PMID 17556757. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm115.

- ^ * Early 地球 Likely Had 大陆s And Was Habitable. 2005-11-17.

* Cavosie, A. J.; J. W. Valley, S. A., Wilde, and E.I.M.F. Magmatic δ18O in 4400-3900 Ma detrital zircons: A record of the alteration and recycling of crust in the Early Archean. 地球 and 行星ary Science Letters. July 15, 2005, 235 (3–4): 663–681. Bibcode:2005E&PSL.235..663C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.04.028. - ^ Dauphas, N., Robert, F., and Marty, B. The Late Asteroidal and Cometary Bombardment of 地球 as Recorded in Water Deuterium to Protium Ratio. Icarus. 2000, 148 (2): 508–512. Bibcode:2000Icar..148..508D. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6489. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Schopf, J. 化石 证据 of Archaean 生命. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006, 361 (1470): 869–85. PMC 1578735

. PMID 16754604. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834.

. PMID 16754604. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834.

- ^ * Arrhenius, S. The Propagation of 生命 in Space. Die Umschau volume=7. 1903: 32. Bibcode:1980qel..book...32A. Reprinted in Goldsmith, D., (編). The Quest for Extraterrestrial 生命. University Science Books. ISBN 0-19-855704-3.

* Hoyle, F., and Wickramasinghe, C. On the Nature of Interstellar Grains. Astro物理學 and Space Science. 1979, 66: 77–90. Bibcode:1979Ap&SS..66...77H. doi:10.1007/BF00648361.

* Crick, F. H.; Orgel, L. E. Directed 泛种论. Icarus. 1973, 19 (3): 341–348. Bibcode:1973Icar...19..341C. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(73)90110-3. - ^ Peretó, J. Controversies on the origin of 生命 (PDF). Int. Microbiol. 2005, 8 (1): 23–31 [October 7, 2007]. PMID 15906258.

- ^ Manten, A.A. Some problematic shallow-marine structures. Marine Geol. 1966, 4 (3): 227–232 [June 18, 2007]. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(66)90023-5.

- ^ Krumbein, W.E., Brehm, U., Gerdes, G., Gorbushina, A.A., Levit, G. and Palinska, K.A. Biofilm, Biodictyon, Biomat Microbialites, Oolites, 叠层石s, Geophysiology, Global Mechanism, Parahistology. Krumbein, W.E., Paterson, D.M., and Zavarzin, G.A. (編). 化石 and Recent Biofilms: A Natural History of 生命 on 地球 (PDF). Kluwer Academic. 2003: 1–28 [July 9, 2008]. ISBN 1-4020-1597-6.

- ^ Hoehler, T.M., Bebout, B.M., and Des Marais, D.J. The role of 微生物席s in the production of reduced gases on the early 地球. Nature. July 19, 2001, 412 (6844): 324–327 [July 14, 2008]. PMID 11460161. doi:10.1038/35085554.

- ^ Nisbet, E.G., and Fowler, C.M.R. Archaean metabolic 演变 of 微生物席s (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society: 生物學. December 7, 1999, 266 (1436): 2375. PMC 1690475

. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0934.

. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0934.

- ^ Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. Mitochondrial 演变. Science. 1999, 283 (5407): 1476–81. Bibcode:1999Sci...283.1476G. PMID 10066161. doi:10.1126/science.283.5407.1476. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ El Albani, Abderrazak; Bengtson, Stefan; Canfield, Donald E.; Bekker, Andrey; Macchiarelli, Reberto; Mazurier, Arnaud; Hammarlund, Emma U.; Boulvais, Philippe; Dupuy, Jean-Jacques. Large colonial 生命体s with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago. Nature. 2010, 466 (7302): 100–104. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..100A. PMID 20596019. doi:10.1038/nature09166. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Butterfield, N.J. Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the 演变 of sex, 多细胞的ity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic 辐射 of 真核细胞s. Paleo生物學. 2000, 26 (3): 386–404 [2008-09-02]. ISSN 0094-8373. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Butterfield, N.J. Probable Proterozoic fungi. Paleo生物學. 2005, 31 (1): 165–182 [2008-09-02]. ISSN 0094-8373. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031<0165:PPF>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Chen, J.-Y., Oliveri, P., Gao, F., Dornbos, S.Q., Li, C-W., Bottjer, D.J. and Davidson, E.H. Pre寒武纪 动物 生命: Probable Developmental and Adult 刺细胞动物n Forms from Southwest China (PDF). Developmental 生物學. 2002, 248 (1): 182–196 [September 3, 2008]. PMID 12142030. doi:10.1006/dbio.2002.0714. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Bengtson, S. Lipps, J.H., and Waggoner, B.M. , 編. Neoproterozoic — 寒武纪 Biological R演变s (PDF). Paleontological Society P猿rs. 2004, 10: 67–78 [July 18, 2008].

|contribution=被忽略 (幫助) - ^ 59.0 59.1 Marshall, C.R. Explaining the 寒武纪 "Explosion" of 动物s. Annu. Rev. 地球 行星. Sci. 2006, 34: 355–384 [November 6, 2007]. Bibcode:2006AREPS..34..355M. doi:10.1146/annurev.地球.33.031504.103001.

- ^ Conway Morris, S. Once we were worms. New Scientist. August 2, 2003, 179 (2406): 34 [September 5, 2008].

- ^ Sansom I.J., Smith, M.M., and Smith, M.P. The 奥陶纪 辐射 of 脊椎动物. Ahlberg, P.E. (編). Major Events in Early Vertebrate 演变. Taylor and Francis. 2001: 156–171. ISBN 0-415-23370-4.

- ^ Selden, P.A. "Terrestrialization of 动物s". Briggs, D.E.G., and Crowther, P.R. (編). Palaeo生物学 II: A Synthesis. Blackwell. 2001: 71–74 [September 5, 2008]. ISBN 0-632-05149-3.

- ^ 63.0 63.1 Kenrick, P., and Crane, P.R. The origin and early 演变 of plants on land (PDF). Nature. 1997, 389 (6646): 33 [2010-11-10]. Bibcode:1997Natur.389...33K. doi:10.1038/37918. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Laurin, M. How 脊椎动物 Left the Water. Berkeley, California, USA.: University of California Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-520-26647-6.

- ^ MacNaughton, R.B., Cole, J.M., Dalrymple, R.W., Braddy, S.J., Briggs, D.E.G., and Lukie, T.D. First steps on land: Arthropod trackways in 寒武纪-Ordovician eolian sandstone, southeastern Ontario, Canada 請檢查

|url=值 (幫助). 地質學. 2002, 30 (5): 391–394 [2008-09-05]. Bibcode:2002Geo....30..391M. ISSN 0091-7613. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0391:FSOLAT>2.0.CO;2. 已忽略未知參數|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Gordon, M.S, Graham, J.B., and Wang, T. Revisiting the Vertebrate Invasion of the Land. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. September/October 2004, 77 (5): 697–699. doi:10.1086/425182.

- ^ Clack, J.A. Getting a Leg Up on Land. November 2005 [September 6, 2008]. 已忽略未知參數

|newsp猿r=(幫助) - ^ Luo, Z., Chen, P., Li, G., & Chen, M. A new eutriconodont 哺乳动物 and 演化的 development in early 哺乳动物s. Nature. March 2007, 446 (7133): 288–293. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..288L. PMID 17361176. doi:10.1038/nature05627.

- ^ 69.0 69.1 Padian, Kevin. Basal Avialae. Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; & Osmólska, Halszka (eds.) (編). The 恐龙ia Second. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2004: 210–231. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ Sidor, C.A., O'Keefe, F.R., Damiani, R., Steyer, J.S., Smith, R.M.H., Larsson, H.C.E., Sereno, P.C., Ide, O, and Maga, A. 二叠纪 tetrapods from the Sahara show climate-controlled endemism in Pangaea. Nature. 2005, 434 (7035): 886–889 [September 8, 2008]. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..886S. PMID 15829962. doi:10.1038/nature03393. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Benton M.J. When 生命 Nearly Died: The Greatest Mass 灭绝 of All Time. Thames & Hudson. 2005. ISBN 978-0-500-28573-2.

- ^ Ward, P.D.; Botha, J.; Buick, R.; Kock, M.O.; Erwin, D.H.; Garrisson, G.H.; Kirschvink, J.L.; Smith, R. Abrupt and gradual 灭绝 among late 二叠纪 land 脊椎动物 in the Karoo Basin, South Africa. Science. 2005, 307 (5710): 709–714. PMID 15661973. doi:10.1126/science.1107068.

- ^ Benton, M.J. 恐龙 Success in the Triassic: a Noncompetitive Ecological Model (PDF). Quarterly Review of 生物學. March 1983, 58 (1) [September 8, 2008].

- ^ Ruben, J.A., and Jones, T.D. Selective Factors Associated with the Origin of Fur and Feathers. American Zoologist. 2000, 40 (4): 585–596. doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.585.

- ^ Alroy J. The 化石 record of 北美洲n 哺乳动物s: 证据 for a Paleocene 演化的 辐射. Systematic 生物學. 1999, 48 (1): 107–18. PMID 12078635. doi:10.1080/106351599260472. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Simmons, N.B., Seymour,K.L., Habersetzer, J.,and Gunnell, G.F. Primitive Early Eocene bat from Wyoming and the 演变 of flight and echolocation. Nature. 2008, 451 (7180): 818–821. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..818S. PMID 18270539. doi:10.1038/nature06549. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ J. G. M. Thewissen, S. I. Madar, and S. T. Hussain. Ambulocetus natans, an Eocene cetacean (哺乳动物ia) from Pakistan. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. 1996, 191: 1–86.

- ^ Crane, P.R., Friis, E.M., and Pedersen, K.R. The Origin and Early Diversification of Angiosperms. Gee, H. (編). Shaking the Tree: Readings from Nature in the History of 生命. University of Chicago Press. 2000: 233–250 [September 9, 2008]. ISBN 0-226-28496-4.

- ^ Crepet, W.L. Progress in understanding angiosperm history, success, and relationships: Darwin's abominably "perplexing phenomenon" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000, 97 (24): 12939–12941 [September 9 , 2008]. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9712939C. PMC 34068

. PMID 11087846. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.24.12939. 已忽略未知參數

. PMID 11087846. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.24.12939. 已忽略未知參數|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助); - ^ Brunet M., Guy, F., Pilbeam, D., Mackaye, H.T.; et al. A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa. Nature. 2002, 418 (6894): 145–151 [September 9, 2008]. PMID 12110880. doi:10.1038/nature00879. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ De Miguel, C., and M. Henneberg, M. Variation in hominid 脑 size: How much is due to method?. HOMO — Journal of Comparative Human 生物學. 2001, 52 (1): 3–58 [September 9, 2008]. doi:10.1078/0018-442X-00019.

- ^ Leakey, Richard. The Origin of Humankind. Science Masters Series. New York, NY: Basic Books. 1994: 87–89. ISBN 0-465-05313-0.

- ^ Benton, M.J. 6. Reptiles Of The Triassic. Vertebrate Palaeontology. Blackwell. 2004 [November 17, 2008]. ISBN 0-04-566002-6.

- ^ Van Valkenburgh, B. Major patterns in the history of xarnivorous 哺乳动物s. Annual Review of 地球 and 行星ary Sciences. 1999, 27: 463–493. Bibcode:1999AREPS..27..463V. doi:10.1146/annurev.地球.27.1.463.

- ^ 86.0 86.1 MacLeod, Norman. 灭绝!. 2001-01-06 [September 11, 2008].

- ^ Martin, R.E. Cyclic and secular variation in micro化石 bio矿化作用: clues to the bio地球化学的 演变 of Phanerozoic oceans. Global and 行星ary Change. 1995, 11 (1): 1. Bibcode:1995GPC....11....1M. doi:10.1016/0921-8181(94)00011-2.

- ^ Martin, R.E. Secular increase in nutrient levels through the Phanerozoic: Implications for productivity, biomass, and diversity of the marine biosphere. PALAIOS. 1996, 11 (3): 209–219. JSTOR 3515230. doi:10.2307/3515230.

- ^ Gould, S.J. Wonderful 生命: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. Hutchinson Radius. 1990: 194–206. ISBN 0-09-174271-4.

- ^ 90.0 90.1 Rohde, R.A., and Muller, R.A. Cycles in 化石 diversity (PDF). Nature. 2005, 434 (7030): 208–210 [September 22, 2008]. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..208R. PMID 15758998. doi:10.1038/nature03339. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Rudwick, Martin J.S. The Meaning of 化石s 2nd. The University of Chicago Press. 1985: 39. ISBN 0-226-73103-0.

- ^ Rudwick, Martin J.S. The Meaning of 化石s 2nd. The University of Chicago Press. 1985: 24. ISBN 0-226-73103-0.

- ^ Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, 数学s and the Sciences of the Heavens and the 地球. Caves Books Ltd. 1986: 614. ISBN 0-253-34547-2.

- ^ McGowan, Christopher. The Dragon Seekers. Persus Publishing. 2001: 3–4. ISBN 0-7382-0282-7.

- ^ Palmer, D. 地球 Time: Exploring the Deep Past from Victorian England to the Grand Canyon. Wiley. 2005. ISBN 780470022214 請檢查

|isbn=值 (幫助). - ^ Greene, Marjorie; David Depew. The Philosophy of 生物学: An Episodic History. Cambridge University Press. 2004: 128–130. ISBN 0-521-64371-6.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J.; Iwan Rhys Morus. Making Modern Science. The University of Chicago Press. 2005: 168–169. ISBN 0-226-06861-7.

- ^ Rudwick, Martin J.S. The Meaning of 化石s 2nd. The University of Chicago Press. 1985: 200–201. ISBN 0-226-73103-0.

- ^ Rudwick, Martin J.S. Worlds Before Adam: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Reform. The University of Chicago Press. 2008: 48. ISBN 0-226-73128-6.

- ^ 100.0 100.1 Buckland W & Gould SJ. 地质学 and Mineralogy Considered With Reference to Natural Theology (History of 古生物学). Ayer Company Publishing. 1980. ISBN 978-0-405-12706-9.

- ^ Shu, D-G., Conway Morris, S., Han, J.; et al. Head and backbone of the Early 寒武纪 vertebrate Haikouichthys. Nature. January 2003, 421 (6922): 526–529 [September 21, 2008]. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..526S. PMID 12556891. doi:10.1038/nature01264.

- ^ Everhart, Michael J. Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press. 2005: 17. ISBN 0-253-34547-2.

- ^ Gee, H. (編). Rise of the Dragon: Readings from Nature on the Chinese 化石 Record. Chicago, Ill. ;London: University of Chicago Press. 2001: 276 [September 21, 2008]. ISBN 0-226-28491-3.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. 演变:The History of an Idea. University of California Press. 2003: 351–352. ISBN 0-520-23693-9.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. 演变:The History of an Idea. University of California Press. 2003: 325–339. ISBN 0-520-23693-9.

- ^ Crick, F.H.C. On degenerate templates and the adaptor hypothesis 請檢查

|url=值 (幫助) (PDF). 1955 [October 4, 2008]. - ^ Sarich V.M., and Wilson A.C. Immunological time scale for hominid 演变. Science. 1967, 158 (3805): 1200–1203 [September 21, 2008]. Bibcode:1967Sci...158.1200S. PMID 4964406. doi:10.1126/science.158.3805.1200. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Page, R.D.M, and Holmes, E.C. Molecular 演变: A Phylogenetic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell Science. 1998: 2. ISBN 0-86542-889-1.