苯丙胺

此条目可参照英语维基百科相应条目来扩充,此条目在对应语言版为高品质条目。 |

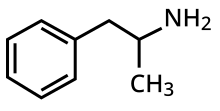

安非他命(英文名称:Amphetamine[note 1]为一种中枢神经兴奋剂,用来治疗注意力不足过动症、嗜睡症、和肥胖症。“Amphetamine”一名撷取自 alpha‑methylphenethylamine。

安非他命于公元1887年被发现,以两种对映异构体的形式存在[note 2] ,分别是左旋安非他命和右旋安非他命。

准确来说,安非他命指的是特定的化学物质-外消旋纯胺类型态[24][25],这个物质等同于安非他命的的两个对映异构体:左旋安非他命和右旋安非他命的等比化合物之纯胺类型态。 然而,实际上安非他命一词已被广泛的用来表示任何由安非他命对映异构体构成的物质或安非他命对映异构体本身。[21][26][25]

安非他命是一种中枢神经兴奋剂,适度适量地使用能提升整体冲动控制能力(inhibitory control)[27][28]。在医疗用的剂量范围内,安非他命能带来情绪以及执行功能的变化,例如:欣快感的增强、性欲的改变、清醒度的提升、大脑执行功能的进化。安非他命所改变的生理反应包含:减少反应时间、降低疲劳、以及肌耐力的增强。然而,若摄取剂量远超过医疗用的剂量范围,将会导致大脑执行功能受损以及横纹肌溶解症。 摄取过分超越医疗用剂量范围的安非他命可引发严重的药物成瘾。然而长期摄取医疗剂量范围的安非他命并不会产生上瘾的风险。

此外,服用远超医疗用剂量范围的安非他命会引起精神疾病(例如:妄想[参 1]、偏执[参 2])。然而长期摄取医疗剂量范围的安非他命并不会引起上述疾病。

那些为享乐而摄入的安非他命通常会远超过医疗用剂量范围,且伴随着非常严重甚至致命的副作用。 [sources 1]

历史上,安非他命也曾被用来治疗鼻塞(nasal congestion)和抑郁。

安非他命也被用来提升表现、促进大脑的认知功能及在助兴时(非医疗用途情况下)被作为增强性欲[a]、和欣快感促进剂。

安非他命在许多国家为合法的处方药[参 3]。然而,私自散布和囤积安非他命被视为非法行为,因为安非他命被用于非医疗用途的助兴可能性极高。[sources 2]

首个药用安非他命的药品名称为Benzedrine。当今药用安非他命[参 4]以下列几种形式存在:外消旋安非他命[参 5]、Adderall [note 3]。 、dextroamphetamine、或对人体无药效的前驱药物体[参 6]:lisdexamfetamine。

安非他命借着自身作用于儿茶酚胺神经传导元素:正肾上腺素及多巴胺的特点来活化trace amine receptor ,进而增加单胺类神经递质和神经递质(excitatory neurotransmitter)在脑内的活动。[sources 3]

安非他命属于替代性苯乙胺类的物质。由安非他命衍伸出的物质被归纳在替代性苯乙胺[参 7]的分类中[note 4],比如说:安非他酮[参 8]、 cathinone、 MDMA、 和 甲基苯丙胺[参 9]。安非他命也与人体内可自然生成的两个属于痕量胺的神经传导物质--特别是 phenethylamine 和 N-Methylphenethylamine--有关。 Phenethylamine 是安非他命的原始化合物,而N-methylphenethylamine则是安非他命的位置异构体(只有在甲基族中才会区分出此位置异构体)。[sources 4]

用途

医疗

安非他命是用来治疗注意力不足过动症(ADHD)、嗜睡症(一种睡眠疾病)、和肥胖症。有时候安非他命会以仿单标示外使用的方式处方来治疗顽固性忧郁症及顽固性强迫症[1][10] [43] [50]。 在动物试验中,已知非常高剂量的安非他命会造成某些动物的多巴胺系统和神经系统的受损。[51][52] 但是,在人体试验中,注意力不足过动症患者在接受安非他命的治疗后,则发现安非他命可促进大脑的发育及神经的成长。[53][54][55]

回顾许多核磁共振照影(MRI)的研究后发现,长期以安非他命治疗注意力不足过动症患者能显著降低患者大脑结构及大脑执行功能上的异常。并且优化大脑中数个部位,例如:基底神经节的右尾状核。 [53][54][55]

众多临床研究的系统性及统合性回顾已确立长期使用安非他命治疗注意力不足过动症的疗效及安全。[56][57][58]

持续长达两年的随机对照试验[参 10][b]结果显示:长期使用安非他命治疗注意力不足过动症,是有效且安全的。[56][58]

两个系统性/统合性回顾的结果显示长期且持续地使用中枢神经兴奋剂治疗注意力不足过动症能有效地减少注意力不足过动症的核心症状(核心症状即为:过动、冲动和分心/无法专心)、增进生活品质、提升学业成就、广泛地强化大脑的执行功能。[note 5] 这些执行功能分别与下列项目有关:学业、反社会行为、驾驶习惯、药物滥用、肥胖、职业、日常活动、自尊心、服务使用(例如:学习、职业、健康、财金、和法律等)、社交功能。[57][58]

一篇系统性/统合性回顾标志了一个重要发现:一个为期九个月的随机双盲试验中,持续以安非他命治疗的ADHD患者,其智力商数平均增加4.5单位[注 1],且在专注力、冲动、过动的改善皆呈现持续进步的态势。[56] 另一篇系统性/统合性回顾则指出:根据迄今为止为时最长的数个临床追踪研究[参 11],可以得到一个结论:即便从儿童时期开始以中枢神经兴奋剂治疗直到老年,中枢神经兴奋剂都能持续有效地控制ADHD的症状并且减少物质滥用的风险。[58] 研究表明,ADHD与大脑的执行功能受损有关。而这些受损的执行功能分别与大脑中部分的神经传导系统有关[参 12]。[59] ;又此部分受损的神经传导系统和中脑皮质激素-多巴胺[参 13]的传导及蓝斑核[参 14]和前额叶[参 15]中的正肾上腺素[参 16]的传导相关。[59]

中枢神经兴奋剂,例如:methylphenidate和安非他命对于治疗ADHD都是有效的,因为中枢神经兴奋剂刺激了上述神经系统中的神经传导物质活动。[29][59] [60]

至少超过80%的ADHD患者在使用中枢神经兴奋剂治疗后,其ADHD的症状可以获得改善。[61]

使用中枢神经兴奋剂治疗的ADHD患者相较之下,普遍与同侪及家庭成员的关系较佳并且在学校拥有较好的表现。兴奋剂能使ADHD患者较不易分心、冲动、且拥有较长的专注力时间和范围。[62] [63]

根据考科蓝协作组织[参 17]所提供的文献回顾结果[note 6]指出:使用中枢神经兴奋剂治疗的ADHD患者即便其症状改善,相较于使用非中枢神经兴奋剂,仍因副作用而有较高的停药率。[65] [66]

回顾结果也发现,中枢神经兴奋剂并不会恶化抽动综合症的症状,例如:妥瑞氏症,除非服用dextroamphetamine[c]的剂量过高才有可能在部分妥瑞氏症合并注意力不足过动症患者身上观察到抽动综合症的症状恶化。[67]

中枢神经兴奋剂只要依照医师指示用药,都是相当安全的。[68][69][69][70] 中枢神经兴奋剂,例如:利他能与专思达,可能导致:心悸、头痛、胃痛、丧失食欲、失眠、因相对专注而变得冷淡(面无表情)等副作用,因此6岁以下的儿童不适宜服用。(副作用产生与否因人而异) [71]

随着时间推进与各方的努力,中枢神经兴奋剂的相关副作用已可借由包括但不限于剂量调整、服药时间、饭前饭后服用、服药频率等服药模式之改变以及改变药物组合等方式获得相当程度的减少。[72] [73] [74] [69] [75]

提升表现

- 认知方面(Cognitive)

公元2015年中,一篇系统性回顾[参 18]和一篇元分析/整合分析[参 19]回顾了数篇优秀的临床试验[参 20]报告后发现, 低剂量(医疗用剂量)的安非他命能适度但不强烈地促进一个人的认知功能,包含工作记忆(working memory)、长期的情节记忆(episodic memory)、冲动控制以及在一些方面的注意力(attention)。 [27] [28] 安非他命强化认知功能的效果已知是部分透过间接活化在大脑前额叶(prefrontal cortex)的dopamine receptor D1 和adrenoceptor α2。 [29] [27] 一篇2014年的系统性回顾发现低剂量(医疗用剂量)的安非他命能促进memory consolidation,进而提升一个人的recall of information。 [76] 低剂量(医疗用剂量)的安非他命也可增加大脑皮层(质)区的效率,这能让一个人的工作记忆(working memory)获得进步。 [29] [77] 安非他命和其他用于治疗ADHD的中枢神经刺激剂能透过提升task saliency来增加一个人去做事情的动机、并强化一个人的警觉心(清醒度),因而能刺激一个人开始做“以目标为导向”的行为。 [29] [78] [79] 中枢神经兴奋剂(例如:安非他命)能提升一个人在困难且枯燥的任务中的表现。 [29] [79] [80] 超过医疗用剂量范围(包含其误差范围及容许最大上限)的安非他命剂量将不利于工作记忆(working memory)和其他的认知功能。 [29][79]

- 生理(physical)

虽然安非他命可以提升速度、耐力(延迟疲劳的发生)、肌耐力、身体素质和警觉心并减少心理反应时间。[30][34] [30] [81] [82] 然而,“非因医疗需求使用安非他命”在各种运动场合都是被严格禁止的。[83] [84]

安非他命借由抑制多巴胺在中枢神经系统中的回收及外流来促进耐力和反应时间的提升。 [81][82] [85] 安非他命和其他作用于多巴胺系统的药物一样,都能增加在固定施力(levels of perceived exertion)下的动力(能)输出。这是因为安非他命能夺取(override)体温的“安全开关”的控制权并将身体核心温度(core temperature limit)的上限提高以取得在体温安全上限提高前被身体保留的能量。 [82] [86] [87] 于医疗用剂量范围(包含其误差范围),安非他命的副作用不至于影响运动员的运动表现; [30][81] 然而,当摄取的剂量过多时,安非他命可能会引起严重的后果,例如:横纹肌溶解症和体温过高。 [31][33] [81]

医疗上的禁忌

根据International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS)和美国食品药物管理局 (USFDA), [note 7]

安非他命不建议处方给有药物滥用、心血管疾病、对于各种刺激严重反应过度、和严重焦虑历史的人。 [note 8][89][90]

安非他命也不被建议处方给正经历动脉血管硬化(血管硬化)、中度到重度高血压、青光眼(眼压过高)、或甲状腺机能亢进(身体在体内制造出过量的甲状腺 贺尔蒙/激素)的人。 [89][90][91]

曾对中枢神经刺激剂有药物过敏的人以及正在服用单胺氧化酶抑制剂 (MAOI)或单胺氧化酶抑制剂类药物 (MAOIs),可能不适合使用安非他命。即便曾有合并使用安非他命和单胺氧化酶抑制剂后仍一切平安的案例。 [89][90] [92][93] IPCS和美国食品药物管理局也同意患有神经性厌食症(anorexia nervosa)、双极性情感疾患(bipolar disorder)、忧郁、高血压、mania、思觉失调症、Raynaud's phenomenon、心脏病发(seizures)、抽动综合症(tics)、妥瑞氏症(Tourette's disease)、和有甲状腺问题、肝肾问题的人在使用安非他命时应密切追踪上述疾病的变化。 [89][90]

人体试验证明,医疗用剂量下的安非他命并不会导致胎儿或新生儿畸形(i.e., it is not a human teratogen)。然而超越医疗用剂量甚多的安非他命确实会增加胎儿或新生儿畸形的机会。 [90]

研究观察发现,安非他命会进入母亲的母乳中,因此建议母亲不要在使用安非他命药物的期间内授乳。 [89][90]

由于安非他命可能影响食欲继而导致可反转的身高及体重的成长迟缓, [note 9] ,因此建议儿童或青少年在用药期间定期测量自己的身高及体重。 [89]

副作用

生理

心理

严重过量

安非他命过量使用会引起许多症状,然而在适当的医疗照护下,不至于死亡。 [90][95]

药物过量症状的严重度与剂量成正比;与身体对安非他命的药物耐受性成反比。 [34][90] 已知每天摄取达到5公克的安非他命(每天最大摄取量的五十倍)会导致身体对安非他命产生药物耐受性。 [90] 严重过量的安非他命摄取所致的症状列于下方;安非他命中毒一旦到达出现全身抽蓄(convulsion)和昏厥(coma)则必须立刻急救以避免死亡。 [31][34] 在2013年,安非他命、甲基安非他命和其他列于ICD-10 第五章:精神和行为障碍§使用化学药物、物质或酒精引起的精神和行为障碍中的安非他命相关物质的过量使用在世界上共导致3788人死亡。(3,425–4,145 人死亡、 95% 信赖区间)。 [note 10][96]

被过度活化达到病态程度的mesolimbic pathway(一个连接腹侧被盖区(ventral tegmental area)和伏隔核(nucleus accumbens)的多巴胺通道),在安非他命的成瘾中扮演着主要的脚色。 [97] [98]

当一个人经常服用严重过量的安非他命,将伴随安非他命成瘾的高度风险, 因为持续过量的安非他命会逐渐增加accumbal ΔFosB(“成瘾”与否的分子开关和主控蛋白 原文:a "molecular switch" and "master control protein" for addiction.)的档次。 [99][100][101] 一旦伏隔核的ΔFosB破表(over-expressed),这个人的“成瘾性行为”[注 2](例如:出现试图取得安非他命的冲动行为)将开始随之增加。 [99][102] 虽然目前没有治疗安非他命成瘾的有效药物,但规律的且每次都有持续一定时间的有氧运动能降低安非他命的成瘾风险也是治疗安非他命成瘾的天然疗法。 [103][104] [sources 5] 运动能提升临床治疗的预后,且可能与认知行为治疗(目前已知最有效的安非他命成瘾的临床治疗法)相搭配为combination therapy。 [103][105][106]

| 生物系统 | 轻度、中度过量[31][34][90] | 过量[sources 6] |

|---|---|---|

| 心脏血管系统 | ||

| 中枢神经系统 | ||

| 肌肉骨骼系统 |

| |

| 呼吸系统 |

|

|

| 生殖泌尿系统 | ||

| 其他 |

成瘾

| “成瘾及生理、心理依赖”的相关术语词汇表[108][100][109][110] | |

|---|---|

| |

长期服用远超医疗用剂量范围的安非他命会导致安非他命成瘾(Addiction)。然而长期摄取医疗剂量范围的安非他命并不会引起上述问题。 [37][38][39] 安非他命滥用(例如:长期摄取严重过量的安非他命)会导致大脑对于该剂量产生药物耐受性。渐渐地,滥用者必须服用更大量的安非他命以换取同样的效果。 [111][112]

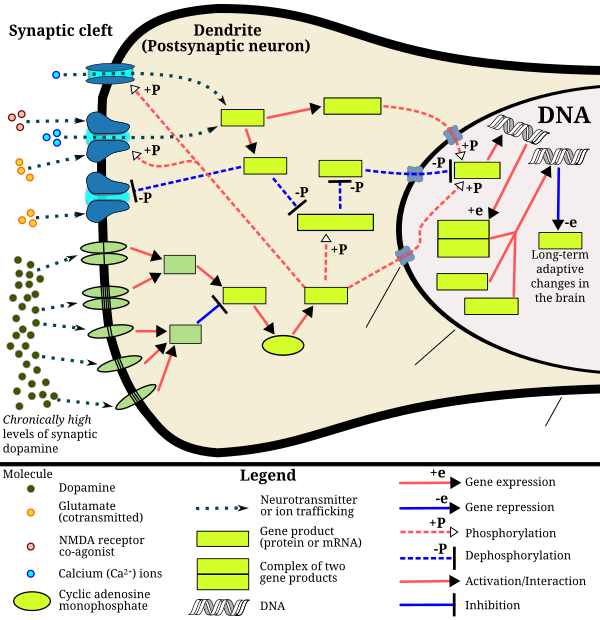

分子生物机转(Biomolecular mechanisms)

当前关于“长期安非他命滥用所致的成瘾”的模型(model)中,已知会改变一些脑部的结构(特别是伏隔核) [113][114][115]。 造成脑部结构改变的最重要的转录因子(transcription factor)为:ΔFosB、 cAMP response element binding protein (CREB)、和 nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)。 [note 11] [114] ΔFosB 在药物成瘾的发展过程中扮演着至关重要的脚色,主要的原因在于其在 伏隔核中D1-type medium spiny neurons的破表(over-expression),为“成瘾”及“成瘾衍生的行为”及“神经元为了适应新常态所做的调适”的充分且必要条件。 [note 12] [99][100][114]

一旦ΔFosB充分破表(sufficiently overexpressed),将诱发越来越严重的成瘾状态并伴随ΔFosB值的持续创新高。 [99][100] ΔFosB已被证明与酒精成瘾、大麻成瘾、古柯碱成瘾、派醋甲酯成瘾、尼古丁成瘾、鸭片成瘾、phencyclidine成瘾、异丙酚、和安非他命的替代性物质成瘾、及其他成瘾有关。 [sources 7] ΔJunD为一个转录因子;而G9a为组织蛋白甲基转移酶的一种。ΔJunD和G9a直接与伏隔核中的ΔFosB值的升高成反比。 [100][114][119]

利用载体让伏隔核中的ΔJunD充分破表,可以使由长期药物滥用所致的渐进式神经元和行为改变完全停止。(比如说:ΔFosB所致的改变)。 [114] ΔFosB也在人们于天然酬赏(natural reward)中的行为反应调节上扮演重要的脚色。天然酬赏(natural rewards)包含:美味的食物(palatable food)、性爱(sex)、运动(exercise)、......。 [102][114][120] 因为天然酬赏以及成瘾性药物皆会激发ΔFosB(这些酬赏让大脑刺激ΔFosB的增加。原文:i.e., they cause the brain to produce more of it),长期过度地从事上述行为将可能导致类似的成瘾之病理生理(pathological)。 [102][114]

Consequently, ΔFosB is the most significant factor involved in both amphetamine addiction and amphetamine-induced sex addictions, which are compulsive sexual behaviors that result from excessive sexual activity and amphetamine use.[102][121][122] These sex addictions are associated with a dopamine dysregulation syndrome which occurs in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs.[102][120]

The effects of amphetamine on gene regulation are both dose- and route-dependent.[115] Most of the research on gene regulation and addiction is based upon animal studies with intravenous amphetamine administration at very high doses.[115] The few studies that have used equivalent (weight-adjusted) human therapeutic doses and oral administration show that these changes, if they occur, are relatively minor.[115] This suggests that medical use of amphetamine does not significantly affect gene regulation.[115]

Pharmacological treatments

截至May 2014年[update] there is no effective pharmacotherapy for amphetamine addiction.[123][124][125] Reviews from 2015 and 2016 indicated that TAAR1-selective agonists have significant therapeutic potential as a treatment for psychostimulant addictions;[46][126] however, 截至February 2016年[update] the only compounds which are known to function as TAAR1-selective agonists are experimental drugs.[46][126] Amphetamine addiction is largely mediated through increased activation of dopamine receptors and co-localized NMDA receptors[note 13] in the nucleus accumbens;[98] magnesium ions inhibit NMDA receptors by blocking the receptor calcium channel.[98][127] One review suggested that, based upon animal testing, pathological (addiction-inducing) psychostimulant use significantly reduces the level of intracellular magnesium throughout the brain.[98] Supplemental magnesium[note 14] treatment has been shown to reduce amphetamine self-administration (i.e., doses given to oneself) in humans, but it is not an effective monotherapy for amphetamine addiction.[98]

Behavioral treatments

Cognitive behavioral therapy is currently the most effective clinical treatment for psychostimulant addictions.[106] Additionally, research on the neurobiological effects of physical exercise suggests that daily aerobic exercise, especially endurance exercise (e.g., marathon running), prevents the development of drug addiction and is an effective adjunct therapy (i.e., a supplemental treatment) for amphetamine addiction.[sources 5] Exercise leads to better treatment outcomes when used as an adjunct treatment, particularly for psychostimulant addictions.[103][105][128] In particular, aerobic exercise decreases psychostimulant self-administration, reduces the reinstatement (i.e., relapse) of drug-seeking, and induces increased dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) density in the striatum.[102][128] This is the opposite of pathological stimulant use, which induces decreased striatal DRD2 density.[102] One review noted that exercise may also prevent the development of a drug addiction by altering ΔFosB or c-Fos immunoreactivity in the striatum or other parts of the reward system.[104]

| 神经可塑性和行为可塑性的形式 | 增强物的种类 | 来源 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 鸦片类 | 中枢神经刺激剂 | 高脂肪或高糖食物 | 性交 | 运动与神经元关系 | 环境丰富化 | ||

| 伏隔核中D1-type中的ΔFosB表现 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [102] |

| 行为可塑性 | |||||||

| 摄取量的增加 | 有 | 有 | 有 | [102] | |||

| 中枢神经刺激剂跨越-敏化作用 | 有 | 不适用 | 有 | 有 | 削减 | 削减 | [102] |

| 未经过处方而自行私下摄取中枢神经刺激剂 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [102] | |

| 强化“在特定地点摄取兴奋剂的习惯” | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [102] |

| 强化“试图取得该致瘾药物的行为” | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [102] | ||

| 神经化学物质的可塑性 | |||||||

| 伏隔核中CREB磷酸化 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [102] | |

| 伏隔核中对于多巴胺的过敏反应 | 没有 | 有 | 没有 | 有 | [102] | ||

| 经过变动的纹状体多巴胺接收器的讯号发送 | ↓DRD2 , ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2 , ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD2 | ↑DRD2 | [102] | |

| 经过变动的纹状体鸦片样肽受体的讯号发送 | 未改变,或 ↑μ-鸦片接收器 |

↑μ-鸦片接收器 ↑κ-鸦片接收器 |

↑μ-鸦片接收器 | ↑μ-鸦片接收器 | 未改变 | 未改变 | [102] |

| 发生于纹状体鸦片肽的改变 | ↑强啡肽 脑啡肽未改变 |

↑强啡肽 | ↓脑啡肽 | ↑强啡肽 | ↑强啡肽 | [102] | |

| 多巴胺通道的神经突触的可塑性 | |||||||

| 伏隔核中树突的数量 | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [102] | |||

| 伏隔核中树突棘的密度 | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [102] | |||

注解:DRD2 = 多巴胺受体D2;↑ = 上升;↓ = 下降

依赖和戒断症状 Dependence and withdrawal

According to another Cochrane Collaboration review on withdrawal in individuals who compulsively use amphetamine and methamphetamine, "when chronic heavy users abruptly discontinue amphetamine use, many report a time-limited withdrawal syndrome that occurs within 24 hours of their last dose."[129] This review noted that withdrawal symptoms in chronic, high-dose users are frequent, occurring in up to 87.6% of cases, and persist for three to four weeks with a marked "crash" phase occurring during the first week.[129] Amphetamine withdrawal symptoms can include anxiety, drug craving, depressed mood, fatigue, increased appetite, increased movement or decreased movement, lack of motivation, sleeplessness or sleepiness, and lucid dreams.[129] The review indicated that the severity of withdrawal symptoms is positively correlated with the age of the individual and the extent of their dependence.[129] Manufacturer prescribing information does not indicate the presence of withdrawal symptoms following discontinuation of amphetamine use after an extended period at therapeutic doses.[91][130][131]

Toxicity and psychosis

In rodents and primates, sufficiently high doses of amphetamine cause dopaminergic neurotoxicity, or damage to dopamine neurons, which is characterized by dopamine terminal degeneration and reduced transporter and receptor function.[132][133] There is no evidence that amphetamine is directly neurotoxic in humans.[134][135] However, large doses of amphetamine may indirectly cause dopaminergic neurotoxicity as a result of hyperpyrexia, the excessive formation of reactive oxygen species, and increased autoxidation of dopamine.[sources 8] Animal models of neurotoxicity from high-dose amphetamine exposure indicate that the occurrence of hyperpyrexia (i.e., core body temperature ≥ 40 °C) is necessary for the development of amphetamine-induced neurotoxicity.[133] Prolonged elevations of brain temperature above 40 °C likely promote the development of amphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in laboratory animals by facilitating the production of reactive oxygen species, disrupting cellular protein function, and transiently increasing blood–brain barrier permeability.[133]

A severe amphetamine overdose can result in a stimulant psychosis that may involve a variety of symptoms, such as delusions and paranoia.[35] A Cochrane Collaboration review on treatment for amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methamphetamine psychosis states that about 5–15% of users fail to recover completely.[35][138] According to the same review, there is at least one trial that shows antipsychotic medications effectively resolve the symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.[35] Psychosis very rarely arises from therapeutic use.[36][89] }}

交互作用(Interactions)

Many types of substances are known to interact with amphetamine, resulting in altered drug action or metabolism of amphetamine, the interacting substance, or both.[4][139] Inhibitors of the enzymes that metabolize amphetamine (e.g., CYP2D6 and FMO3) will prolong its elimination half-life, meaning that its effects will last longer.[16][139] Amphetamine also interacts with MAOIs, particularly monoamine oxidase A inhibitors, since both MAOIs and amphetamine increase plasma catecholamines (i.e., norepinephrine and dopamine);[139] therefore, concurrent use of both is dangerous.[139] Amphetamine modulates the activity of most psychoactive drugs. In particular, amphetamine may decrease the effects of sedatives and depressants and increase the effects of stimulants and antidepressants.[139] Amphetamine may also decrease the effects of antihypertensives and antipsychotics due to its effects on blood pressure and dopamine respectively.[139] Zinc supplementation may reduce the minimum effective dose of amphetamine when it is used for the treatment of ADHD.[note 15][143]

In general, there is no significant interaction when consuming amphetamine with food, but the pH of gastrointestinal content and urine affects the absorption and excretion of amphetamine, respectively.[139] Acidic substances reduce the absorption of amphetamine and increase urinary excretion, and alkaline substances do the opposite.[139] Due to the effect pH has on absorption, amphetamine also interacts with gastric acid reducers such as proton pump inhibitors and H2 antihistamines, which increase gastrointestinal pH (i.e., make it less acidic).[139]

药学(Pharmacology)

药效动力学(Pharmacodynamics)

苯丙胺在多巴胺能神经元的药物效应动力学

|

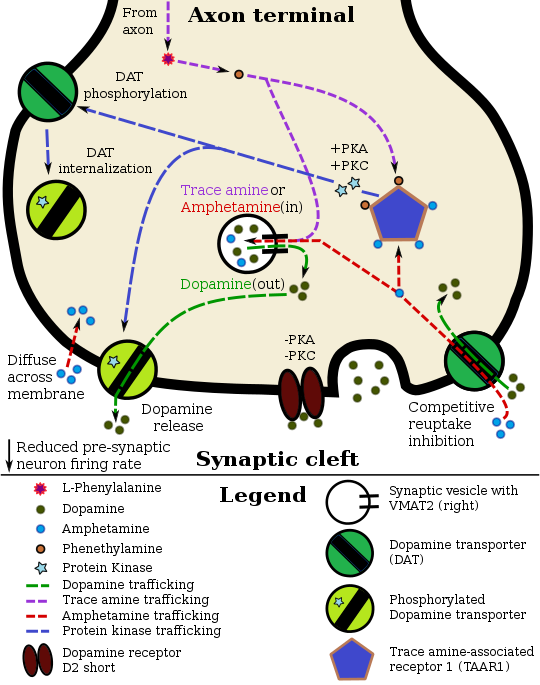

Amphetamine exerts its behavioral effects by altering the use of monoamines as neuronal signals in the brain, primarily in catecholamine neurons in the reward and executive function pathways of the brain.[45][60] The concentrations of the main neurotransmitters involved in reward circuitry and executive functioning, dopamine and norepinephrine, increase dramatically in a dose-dependent manner by amphetamine due to its effects on monoamine transporters.[45][60][144] The reinforcing and motivational salience-promoting effects of amphetamine are mostly due to enhanced dopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic pathway.[29] The euphoric and locomotor-stimulating effects of amphetamine are dependent upon the magnitude and speed by which it increases synaptic dopamine and norepinephrine concentrations in the striatum.[1]

Amphetamine has been identified as a potent full agonist of trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1), a Gs-coupled and Gq-coupled G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) discovered in 2001, which is important for regulation of brain monoamines.[45][145] Activation of TAAR1 increases cAMP production via adenylyl cyclase activation and inhibits monoamine transporter function.[45][146] Monoamine autoreceptors (e.g., D2 short, presynaptic α2, and presynaptic 5-HT1A) have the opposite effect of TAAR1, and together these receptors provide a regulatory system for monoamines.[45][46] Notably, amphetamine and trace amines bind to TAAR1, but not monoamine autoreceptors.[45][46] Imaging studies indicate that monoamine reuptake inhibition by amphetamine and trace amines is site specific and depends upon the presence of TAAR1 co-localization in the associated monoamine neurons.[45] 截至2010年[update] co-localization of TAAR1 and the dopamine transporter (DAT) has been visualized in rhesus monkeys, but co-localization of TAAR1 with the norepinephrine transporter (NET) and the serotonin transporter (SERT) has only been evidenced by messenger RNA (mRNA) expression.[45]

In addition to the neuronal monoamine transporters, amphetamine also inhibits both vesicular monoamine transporters, VMAT1 and VMAT2, as well as SLC1A1, SLC22A3, and SLC22A5.[sources 9] SLC1A1 is excitatory amino acid transporter 3 (EAAT3), a glutamate transporter located in neurons, SLC22A3 is an extraneuronal monoamine transporter that is present in astrocytes, and SLC22A5 is a high-affinity carnitine transporter.[sources 9] Amphetamine is known to strongly induce cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) gene expression,[153][154] a neuropeptide involved in feeding behavior, stress, and reward, which induces observable increases in neuronal development and survival in vitro.[154][155][156] The CART receptor has yet to be identified, but there is significant evidence that CART binds to a unique Gi/Go-coupled GPCR.[156][157] Amphetamine also inhibits monoamine oxidase at very high doses, resulting in less dopamine and phenethylamine metabolism and consequently higher concentrations of synaptic monoamines.[18][158] In humans, the only post-synaptic receptor at which amphetamine is known to bind is the 5-HT1A receptor, where it acts as an agonist with micromolar affinity.[159][160]

The full profile of amphetamine's short-term drug effects in humans is mostly derived through increased cellular communication or neurotransmission of dopamine,[45] serotonin,[45] norepinephrine,[45] epinephrine,[144] histamine,[144] CART peptides,[153][154] endogenous opioids,[161][162][163] adrenocorticotropic hormone,[164][165] corticosteroids,[164][165] and glutamate,[147][149] which it effects through interactions with CART, 5-HT1A, EAAT3, TAAR1, VMAT1, VMAT2, and possibly other biological targets.[sources 10]

Dextroamphetamine is a more potent agonist of TAAR1 than levoamphetamine.[166] Consequently, dextroamphetamine produces greater CNS stimulation than levoamphetamine, roughly three to four times more, but levoamphetamine has slightly stronger cardiovascular and peripheral effects.[34][166]

Dopamine

In certain brain regions, amphetamine increases the concentration of dopamine in the synaptic cleft.[45] Amphetamine can enter the presynaptic neuron either through DAT or by diffusing across the neuronal membrane directly.[45] As a consequence of DAT uptake, amphetamine produces competitive reuptake inhibition at the transporter.[45] Upon entering the presynaptic neuron, amphetamine activates TAAR1 which, through protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) signaling, causes DAT phosphorylation.[45] Phosphorylation by either protein kinase can result in DAT internalization (non-competitive reuptake inhibition), but PKC-mediated phosphorylation alone induces the reversal of dopamine transport through DAT (i.e., dopamine efflux).[45][167] Amphetamine is also known to increase intracellular calcium, an effect which is associated with DAT phosphorylation through an unidentified Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CAMK)-dependent pathway, in turn producing dopamine efflux.[145][147][168] Through direct activation of G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels, TAAR1 reduces the firing rate of dopamine neurons, preventing a hyper-dopaminergic state.[169][170][171]

Amphetamine is also a substrate for the presynaptic vesicular monoamine transporter, VMAT2.[144][172] Following amphetamine uptake at VMAT2, amphetamine induces the collapse of the vesicular pH gradient, which results in the release of dopamine molecules from synaptic vesicles into the cytosol via dopamine efflux through VMAT2.[144][172] Subsequently, the cytosolic dopamine molecules are released from the presynaptic neuron into the synaptic cleft via reverse transport at DAT.[45][144][172]

Norepinephrine

Similar to dopamine, amphetamine dose-dependently increases the level of synaptic norepinephrine, the direct precursor of epinephrine.[47][60] Based upon neuronal TAAR1 mRNA expression, amphetamine is thought to affect norepinephrine analogously to dopamine.[45][144][167] In other words, amphetamine induces TAAR1-mediated efflux and non-competitive reuptake inhibition at phosphorylated NET, competitive NET reuptake inhibition, and norepinephrine release from VMAT2.[45][144]

Serotonin

Amphetamine exerts analogous, yet less pronounced, effects on serotonin as on dopamine and norepinephrine.[45][60] Amphetamine affects serotonin via VMAT2 and, like norepinephrine, is thought to phosphorylate SERT via TAAR1.[45][144] Like dopamine, amphetamine has low, micromolar affinity at the human 5-HT1A receptor.[159][160]

Other neurotransmitters, peptides, and hormones

Acute amphetamine administration in humans increases endogenous opioid release in several brain structures in the reward system.[161][162][163] Extracellular levels of glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, have been shown to increase in the striatum following exposure to amphetamine.[147] This increase in extracellular glutamate presumably occurs via the amphetamine-induced internalization of EAAT3, a glutamate reuptake transporter, in dopamine neurons.[147][149] Amphetamine also induces the selective release of histamine from mast cells and efflux from histaminergic neurons through VMAT2.[144] Acute amphetamine administration can also increase adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosteroid levels in blood plasma by stimulating the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.[43][164][165]

药物代谢动力学

安非他命的口服生物体可利用率[参 21]与肠胃的pH值连动; [139] 安非他命非常容易在肠道被吸收,dextroampetamine的生体可利用率在多数的情况下高于75%。 [2] 安非他命呈弱碱性,其pKa值介于9–10之间;[4] 因此,当pH值呈碱性时,多数的安非他命会以其易溶于脂类的纯胺类型态形式存在。在此情况下,身体会通过肠道上皮组织富含脂类的细胞膜[参 22]来吸收安非他命。 [4] [139] 相反地,酸性的pH值表示安非他命主要以易溶于水的离子[参 23](盐)形式存在,因此较少能被吸收。 [4] 大约15–40%循环于血管中的安非他命与血浆蛋白[参 24]相连接。 [3] 安非他命的对映异构物的半衰期会随着尿液的pH值而有所不同。 [4] 当尿液的酸碱值落在正常范围中,dextroamphetamine和levoamphetamine的半衰期分别为9–11 小时及 11–14 小时。 [4] 酸性饮食会导致安非他命的对映异构物的半衰期降低至8–11 小时;碱性饮食则会使安非他命的对映异构物的半衰期增加到16–31 小时。 [5][11]

成分为安非他命或其衍生物的短效药品大约在口服后三小时在体内达到最高血浆浓度;而成分为安非他命或其衍生物的长效药品则在口服后大约七小时在体内达到最高血浆浓度。 [4]

安非他命主要透过肾脏来代谢,大约30–40%的药物以药物本身原始的型态从酸碱度正常的尿液中排出。 [4] 当尿液是碱性时,安非他命倾向以其纯胺类型态存在,因此较少被排泄。 [4]

当尿液的pH值失常时,各种安非他命的分解物在尿液中重新结合的程度将从最低1%到最高75%。该程度的高低大多取决于于尿液的酸碱值,尿液越酸,结合率越高;尿液愈碱,结合率越低。 [4] 安非他命通常于口服后两天内自体内完全代谢完毕。 [5] 安非他命确切的半衰期及药效作用期随着(小于两天的)重复服用导致的血浆内安非他命浓度(plasma concentration of amphetamine)的增加而延长。[173]

对人体无药效的前驱药物体(prodrug):lisdexamfetamine并不若安非他命一样容易受肠胃道环境的pH值影响; [174] lisdexamfetamine在肠道被吸收进入血管的血液后很快就会透过水解(hydrolysis)的方式转化为dextroamphetamine。而参与这水解反应的酶(enzymes)与红血球有关。 [174]

Lisdexamfetamine的半衰期通常小于一个小时。 [174]

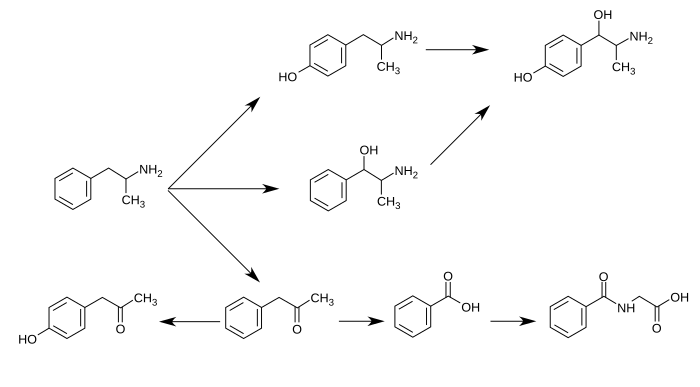

细胞色素 P450 2D6(Cytochrome P450 2D6、或CYP2D6)、多巴胺β羟化酶(Dopamine β-hydroxylase、或DBH)、flavin-containing monooxygenase 3、butyrate-CoA ligase、和 glycine N-acyltransferase为已知在人体中参与[注 3]“安非他命”及“安非他命代谢后之产物”的代谢反应的酶(enzyme)。 [sources 11]

“安非他命代谢后之产物”包含:4-hydroxyamphetamine、4-hydroxynorephedrine、4-hydroxyphenylacetone、苯甲酸(benzoic acid)、马尿酸(hippuric acid)、苯丙醇胺(norephedrine)、苯基丙酮(phenylacetone)[注 4] [4] [5] [6]。

在这些“安非他命代谢后之产物”之中,有实际药效的产物(sympathomimetics)为:4‑hydroxyamphetamine[177]、4‑hydroxynorephedrine[178]、和norephedrine[179]。

安非他命的主要代谢途径包含:aromatic para-hydroxylation、aliphatic alpha- 、beta-hydroxylation、N-oxidation、N-dealkylation、和 deamination。 [4][5]

下图为已知的“安非他命”代谢途径和“安非他命代谢后之产物”: [4][16][6]

苯丙胺的代谢途径

从酸碱度正常的尿液中可发现,大约30–40%的“安非他命”以本身原始的型态排出;大约50%的安非他命以不具药效的“安非他命代谢后之产物”(即为图片中最下列的产物)的型态排出。 [4] 剩下的10–20%则为“安非他命代谢后之产物”之中,有实际药效的产物。 [4] 苯甲酸(Benzoic acid)被butyrate-CoA连接酶(butyrate-CoA ligase)代谢后成为一个中介物质/中间产物(intermediate product):benzoyl-CoA [175] 随后透过glycine N-acyltransferase代谢并转化为马尿酸(hippuric acid)。[176] |

相关的内部生成化合物/混和物(endogenous compound)

历史、社会与文化

合法状态与条件

药品

备注A

- ^ 别名有:1-phenylpropan-2-amine (IUPAC name), α-methylbenzeneethanamine, α-methylphenethylamine, amfetamine (International Nonproprietary Name [INN]), β-phenylisopropylamine, desoxynorephedrine, and speed.[18][21][22]

- ^ 对映异构体指的是两个形状相同但方向相反的两个分子,他们又称为彼此的镜中影像。[23] Levoamphetamine 和 dextroamphetamine 分别被简称为 L-amph 或 levamfetamine (INN) 和 D-amph 或 dexamfetamine (INN) [18]

- ^

"Adderall"是一个品牌名称。因为以下几个安非他命的异构物的英文名称太长了:("dextroamphetamine sulfate, dextroamphetamine saccharate, amphetamine sulfate, and amphetamine aspartate"),因此本文单独以此名称来表示此安非他命的此种混合物。

原文对照:"Adderall" is a brand name as opposed to a nonproprietary name; because the latter ("dextroamphetamine sulfate, dextroamphetamine saccharate, amphetamine sulfate, and amphetamine aspartate" [44]) is excessively long, this article exclusively refers to this amphetamine mixture by the brand name. - ^

“安非他命”一词也意指一个化学分类,但与“替代性安非他命”这个化学分类不同的是,“安非他命”类在学术上并无标准的定义。

[13][25]

有一个“安非他命”类的定义严格限定分类中仅有:安非他命的racemate and enantiomers 和 甲基安非他命methamphetamine的racemate and enantiomers。

[25]

大多数“安非他命”类的定义为那些在药理学上以及结构上与安非他命相关的化合物。

[25]

为避免让amphetamine 和 amphetamines 把读者给弄糊涂了,本条目中仅会使用amphetamine、amphetamines来表示racemic amphetamine, levoamphetamine, and dextroamphetamine;‘替代性安非他命(substituted amphetamines)’来表示安非他命的结构分类。

原文对照: Due to confusion that may arise from use of the plural form, this article will only use the terms "amphetamine" and "amphetamines" to refer to racemic amphetamine, levoamphetamine, and dextroamphetamine and reserve the term "substituted amphetamines" for its structural class. - ^

研究证实,长期以中枢神经兴奋剂治疗ADHD能在下列这些方面产生大幅的进步:学业、驾驶、降低药物滥用、降低肥胖、自尊、和社交功能等。

[57]

在上述领域中,最为突出的领域为: 学业(例如:GPA分数 grade point average、成果测验分数 achievement test scores、受教育的时间长度 length of education、和教育程度 education level) 、自尊(例如:自尊心测验分数 self-esteem questionnaire assessments、尝试自杀的次数、自杀率等) 和社交功能(例如:peer nomination scores、社交技巧、家庭关系 quality of family、同侪关系 quality of peer、和浪漫关系/情侣关系 romantic relationships) [57]

长期以“药物治疗合并行为治疗”的模式来治疗ADHD,能够比单独以药物治疗,产生更全面且更长足的进步。 [57] - ^ 考科蓝协作组织对于历年众多的“随机对照试验”的系统性回顾、数据统整分析后所得出的总结,基本上都是非常有水准且深具参考价值的。 [64]

- ^ 美国食品药物管理局核准的药品使用指引及医疗上的禁忌(放在药盒中的仿单/说明书)并非为了限制医师的决策而是为了避免药商恣意宣称药物的作用。医师可以此为参考,并依照每位病人的实际情况做出独立的判断。 [88]

- ^ 然而根据一篇回顾性论文,安非他命可以处方给曾有药物滥用历史的人,不过需要有对患者适度的药品控管,例如:每天由医护人员配给处方剂量。[1]

- ^ 曾受此副作用的用药者,身高及体重在在短暂停药后恢复至应有水准是可以被预期的。[56][58][94] 根据追踪,持续三年过程不停歇的安非他命治疗(没有合并任何积极减少安非他命副作用的疗法的情况下)平均会减少 2公分的最终身高。 [94]

- ^ “95% 信赖区间”指的是:有95%的几率,真实的死亡人数介于3,425 和 4,145 之间。

- ^

转录因子是一种可以增加或降低一个特定基因的基因表现的蛋白。

原文:Transcription factors are proteins that increase or decrease the expression of specific genes.[116] - ^ 简单来说,这里的“充分且必要(necessary and sufficient)”关系指的是“ΔFosB在伏隔核中的破表(over-expression)”与“成瘾衍生的行为”及“神经元为了适应新常态所做的调适”永远都是一起发生。

- ^ NMDA receptors are voltage-dependent ligand-gated ion channels that requires simultaneous binding of glutamate and a co-agonist (D-serine or glycine) to open the ion channel.[127]

- ^ The review indicated that magnesium L-aspartate and magnesium chloride produce significant changes in addictive behavior;[98] other forms of magnesium were not mentioned.

- ^ The human dopamine transporter contains a high affinity extracellular zinc binding site which, upon zinc binding, inhibits dopamine reuptake and amplifies amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux in vitro.[140][141][142] The human serotonin transporter and norepinephrine transporter do not contain zinc binding sites.[142]

备注B

备注C

注释

英文名称对照

- ^ 英文名称为:delusions

- ^ 英文名称为:paranoia

- ^ 英文名称为:Prescription drug

- ^ 英文名称为:Pharmaceutical amphetamine

- ^ 英文名称为:racemic amphetamine

- ^ 英文名称为:Prodrug

- ^ 英文名称为:substituted amphetamine

- ^ 英文名称为:Bupropion

- ^ 英文名称为:meth-amphetamine

- ^ 英文名称为:Randomized controlled trials

- ^ 英文名称为:follow-up studies

- ^ 英文名称为:neurotransmitter systems

- ^ 英文名称为:dopamine

- ^ 英文名称为:locus coeruleus

- ^ 英文名称为:prefrontal cortex

- ^ 英文名称为:nor-epinephrine或nor-adrenaline

- ^ 英文名称为:Cochrane Collaboration

- ^ 英文名称为:systematic review

- ^ 英文名称为:meta-analysis

- ^ 英文名称为:临床试验

- ^ 英文名称为:bioavailability

- ^ 英文名称为:cell membrane

- ^ 英文名称为:cation

- ^ 英文名称为:plasma protein

引用

- ^ [10][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39]

- ^ [1][25] [29] [30] [31] [40] [41] [42] [32] [26] [24][43]

- ^ [1] [10] [29] [40] [43] [45] [46]

- ^ [47] [48] [49]

- ^ 5.0 5.1 [102][103][104][105][128]

- ^ [22][31][34][95][107]

- ^ [99][102][114][117][118]

- ^ [51][133][136][137]

- ^ 9.0 9.1 [144][147][148][149][150][151][152]

- ^ [45][144][148][149][153][159]

- ^ [4][13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [175] [176]

来源

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 引用错误:没有为名为

Amph Uses的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 2.0 2.1 Dextroamphetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. 2013-02-08.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 3.0 3.1

Amphetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. 2013-02-08.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 Adderall XR Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc: 12–13. December 2013 [2013-12-30].

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4

Amphetamine. Pubchem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Santagati NA, Ferrara G, Marrazzo A, Ronsisvalle G. Simultaneous determination of amphetamine and one of its metabolites by HPLC with electrochemical detection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. September 2002, 30 (2): 247–255. PMID 12191709. doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00330-8.

- ^ amphetamine/dextroamphetamine. Medscape. WebMD.

Onset of action: 30–60 min

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2

Millichap JG. Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD. Millichap JG (编). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD 2nd. New York, USA: Springer. 2010: 112. ISBN 9781441913968.

Table 9.2 Dextroamphetamine formulations of stimulant medication

Dexedrine [Peak:2–3 h] [Duration:5–6 h] ...

Adderall [Peak:2–3 h] [Duration:5–7 h]

Dexedrine spansules [Peak:7–8 h] [Duration:12 h] ...

Adderall XR [Peak:7–8 h] [Duration:12 h]

Vyvanse [Peak:3–4 h] [Duration:12 h] - ^ 9.0 9.1 Brams M, Mao AR, Doyle RL. Onset of efficacy of long-acting psychostimulants in pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Postgrad. Med. September 2008, 120 (3): 69–88. PMID 18824827. doi:10.3810/pgm.2008.09.1909.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Adderall IR Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.: 1–6. October 2015 [2016-05-18].

- ^ 11.0 11.1

AMPHETAMINE. United States National Library of Medicine – Toxnet. Hazardous Substances Data Bank.

Concentrations of (14)C-amphetamine declined less rapidly in the plasma of human subjects maintained on an alkaline diet (urinary pH > 7.5) than those on an acid diet (urinary pH < 6). Plasma half-lives of amphetamine ranged between 16-31 hr & 8-11 hr, respectively, & the excretion of (14)C in 24 hr urine was 45 & 70%.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 12.0 12.1

Mignot EJ. A practical guide to the therapy of narcolepsy and hypersomnia syndromes. Neurotherapeutics. October 2012, 9 (4): 739–752. PMC 3480574

. PMID 23065655. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0150-9.

. PMID 23065655. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0150-9.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3

Glennon RA. Phenylisopropylamine stimulants: amphetamine-related agents. Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (编). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry 7th. Philadelphia, USA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2013: 646–648 [2015-09-11]. ISBN 9781609133450.

The phase 1 metabolism of amphetamine analogs is catalyzed by two systems: cytochrome P450 and flavin monooxygenase. ... Amphetamine can also undergo aromatic hydroxylation to p-hydroxyamphetamine. ... Subsequent oxidation at the benzylic position by DA β-hydroxylase affords p-hydroxynorephedrine. Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

- ^ 14.0 14.1

Taylor KB. Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Stereochemical course of the reaction (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. January 1974, 249 (2): 454–458 [2014-11-06]. PMID 4809526.

Dopamine-β-hydroxylase catalyzed the removal of the pro-R hydrogen atom and the production of 1-norephedrine, (2S,1R)-2-amino-1-hydroxyl-1-phenylpropane, from d-amphetamine.

- ^ 15.0 15.1

Horwitz D, Alexander RW, Lovenberg W, Keiser HR. Human serum dopamine-β-hydroxylase. Relationship to hypertension and sympathetic activity. Circ. Res. May 1973, 32 (5): 594–599. PMID 4713201. doi:10.1161/01.RES.32.5.594.

Subjects with exceptionally low levels of serum dopamine-β-hydroxylase activity showed normal cardiovascular function and normal β-hydroxylation of an administered synthetic substrate, hydroxyamphetamine.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3

Krueger SK, Williams DE. Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism. Pharmacol. Ther. June 2005, 106 (3): 357–387. PMC 1828602

. PMID 15922018. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001.

. PMID 15922018. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001.

"Table 5: N-containing drugs and xenobiotics oxygenated by FMO" - ^ 17.0 17.1 Cashman JR, Xiong YN, Xu L, Janowsky A. N-oxygenation of amphetamine and methamphetamine by the human flavin-containing monooxygenase (form 3): role in bioactivation and detoxication. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. March 1999, 288 (3): 1251–1260. PMID 10027866.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Amphetamine. PubChem Compound. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2015-04-11.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Properties的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Amphetamine. Chemspider.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 21.0 21.1 引用错误:没有为名为

DrugBank1的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 22.0 22.1 Greene SL, Kerr F, Braitberg G. Review article: amphetamines and related drugs of abuse. Emerg. Med. Australas. October 2008, 20 (5): 391–402. PMID 18973636. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2008.01114.x.

- ^

Enantiomer. IUPAC Goldbook. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. [2014-03-14]. doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02069. (原始内容存档于2013-03-17).

One of a pair of molecular entities which are mirror images of each other and non-superposable.

- ^ 24.0 24.1

Guidelines on the Use of International Nonproprietary Names (INNS) for Pharmaceutical Substances. World Health Organization. 1997 [2014-12-01].

In principle, INNs are selected only for the active part of the molecule which is usually the base, acid or alcohol. In some cases, however, the active molecules need to be expanded for various reasons, such as formulation purposes, bioavailability or absorption rate. In 1975 the experts designated for the selection of INN decided to adopt a new policy for naming such molecules. In future, names for different salts or esters of the same active substance should differ only with regard to the inactive moiety of the molecule. ... The latter are called modified INNs (INNMs).

- ^ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5

Yoshida T. Chapter 1: Use and Misuse of Amphetamines: An International Overview. Klee H (编). Amphetamine Misuse: International Perspectives on Current Trends. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers. 1997: 2 [2014-12-01]. ISBN 9789057020810.

Amphetamine, in the singular form, properly applies to the racemate of 2-amino-1-phenylpropane. ... In its broadest context, however, the term [amphetamines] can even embrace a large number of structurally and pharmacologically related substances.

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Amphetamine. Medical Subject Headings. United States National Library of Medicine. [2013-12-16].

- ^ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Spencer RC, Devilbiss DM, Berridge CW. The Cognition-Enhancing Effects of Psychostimulants Involve Direct Action in the Prefrontal Cortex. Biol. Psychiatry. June 2015, 77 (11): 940–950. PMID 25499957. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.013.

The procognitive actions of psychostimulants are only associated with low doses. Surprisingly, despite nearly 80 years of clinical use, the neurobiology of the procognitive actions of psychostimulants has only recently been systematically investigated. Findings from this research unambiguously demonstrate that the cognition-enhancing effects of psychostimulants involve the preferential elevation of catecholamines in the PFC and the subsequent activation of norepinephrine α2 and dopamine D1 receptors. ... This differential modulation of PFC-dependent processes across dose appears to be associated with the differential involvement of noradrenergic α2 versus α1 receptors. Collectively, this evidence indicates that at low, clinically relevant doses, psychostimulants are devoid of the behavioral and neurochemical actions that define this class of drugs and instead act largely as cognitive enhancers (improving PFC-dependent function). This information has potentially important clinical implications as well as relevance for public health policy regarding the widespread clinical use of psychostimulants and for the development of novel pharmacologic treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other conditions associated with PFC dysregulation. ... In particular, in both animals and humans, lower doses maximally improve performance in tests of working memory and response inhibition, whereas maximal suppression of overt behavior and facilitation of attentional processes occurs at higher doses.

引用错误:带有name属性“Unambiguous PFC D1 A2”的<ref>标签用不同内容定义了多次 - ^ 28.0 28.1 Ilieva IP, Hook CJ, Farah MJ. Prescription Stimulants' Effects on Healthy Inhibitory Control, Working Memory, and Episodic Memory: A Meta-analysis. J. Cogn. Neurosci. January 2015: 1–21. PMID 25591060. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00776.

Specifically, in a set of experiments limited to high-quality designs, we found significant enhancement of several cognitive abilities. ... The results of this meta-analysis ... do confirm the reality of cognitive enhancing effects for normal healthy adults in general, while also indicating that these effects are modest in size.

引用错误:带有name属性“Cognitive and motivational effects”的<ref>标签用不同内容定义了多次 - ^ 29.00 29.01 29.02 29.03 29.04 29.05 29.06 29.07 29.08 29.09

Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 318, 321. ISBN 9780071481274.

Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in normal subjects and those with ADHD. ... stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks ... through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors. ...

Beyond these general permissive effects, dopamine (acting via D1 receptors) and norepinephrine (acting at several receptors) can, at optimal levels, enhance working memory and aspects of attention. - ^ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4

Liddle DG, Connor DJ. Nutritional supplements and ergogenic AIDS. Prim. Care. June 2013, 40 (2): 487–505. PMID 23668655. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training ...

Physiologic and performance effects

· Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

· Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

· Improved reaction time

· Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

· Increased acceleration

· Increased alertness and attention to task - ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 引用错误:没有为名为

FDA Abuse & OD的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 32.0 32.1 引用错误:没有为名为

Libido的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 33.0 33.1 引用错误:没有为名为

FDA Effects的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 34.5 34.6 引用错误:没有为名为

Westfall的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Ling W. Shoptaw SJ, Ali R , 编. Treatment for amphetamine psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. January 2009, (1): CD003026. PMID 19160215. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003026.pub3.

A minority of individuals who use amphetamines develop full-blown psychosis requiring care at emergency departments or psychiatric hospitals. In such cases, symptoms of amphetamine psychosis commonly include paranoid and persecutory delusions as well as auditory and visual hallucinations in the presence of extreme agitation. More common (about 18%) is for frequent amphetamine users to report psychotic symptoms that are sub-clinical and that do not require high-intensity intervention ...

About 5–15% of the users who develop an amphetamine psychosis fail to recover completely (Hofmann 1983) ...

Findings from one trial indicate use of antipsychotic medications effectively resolves symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis. - ^ 36.0 36.1 引用错误:没有为名为

Stimulant Misuse的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 37.0 37.1 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 368. ISBN 9780071481274.

Such agents also have important therapeutic uses; cocaine, for example, is used as a local anesthetic (Chapter 2), and amphetamines and methylphenidate are used in low doses to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and in higher doses to treat narcolepsy (Chapter 12). Despite their clinical uses, these drugs are strongly reinforcing, and their long-term use at high doses is linked with potential addiction, especially when they are rapidly administered or when high-potency forms are given.

- ^ 38.0 38.1 Kollins SH. A qualitative review of issues arising in the use of psycho-stimulant medications in patients with ADHD and co-morbid substance use disorders. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. May 2008, 24 (5): 1345–1357. PMID 18384709. doi:10.1185/030079908X280707.

When oral formulations of psychostimulants are used at recommended doses and frequencies, they are unlikely to yield effects consistent with abuse potential in patients with ADHD.

- ^ 39.0 39.1 Stolerman IP. Stolerman IP , 编. Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology. Berlin, Germany; London, England: Springer. 2010: 78. ISBN 9783540686989.

- ^ 40.0 40.1 引用错误:没有为名为

Benzedrine的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

UN Convention的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Nonmedical的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 引用错误:没有为名为

Evekeo的参考文献提供内容 - ^ National Drug Code Amphetamine Search Results. National Drug Code Directory. United States Food and Drug Administration. [2013-12-16]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-16).

- ^ 45.00 45.01 45.02 45.03 45.04 45.05 45.06 45.07 45.08 45.09 45.10 45.11 45.12 45.13 45.14 45.15 45.16 45.17 45.18 45.19 45.20 45.21 45.22 Miller GM. The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity. J. Neurochem. January 2011, 116 (2): 164–176. PMC 3005101

. PMID 21073468. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x.

. PMID 21073468. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x.

- ^ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 Grandy DK, Miller GM, Li JX. "TAARgeting Addiction"-The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution: An Overview of the Plenary Symposium of the 2015 Behavior, Biology and Chemistry Conference. Drug Alcohol Depend. February 2016, 159: 9–16. PMID 26644139. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014.

When considered together with the rapidly growing literature in the field a compelling case emerges in support of developing TAAR1-selective agonists as medications for preventing relapse to psychostimulant abuse.

- ^ 47.0 47.1 引用错误:没有为名为

Trace Amines的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Amphetamine. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. [2013-10-19].

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Amphetamine - a substituted amphetamine的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). NHS Choice. 2016-09-28 [2017-04-04].

- ^ 51.0 51.1 Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, Carvalho F, Bastos Mde L. Toxicity of amphetamines: an update. Arch. Toxicol. August 2012, 86 (8): 1167–1231. PMID 22392347. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5.

- ^ Berman S, O'Neill J, Fears S, Bartzokis G, London ED. Abuse of amphetamines and structural abnormalities in the brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. October 2008, 1141: 195–220. PMC 2769923

. PMID 18991959. doi:10.1196/annals.1441.031.

. PMID 18991959. doi:10.1196/annals.1441.031.

- ^ 53.0 53.1 Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K. Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects. JAMA Psychiatry. February 2013, 70 (2): 185–198. PMID 23247506. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277.

- ^ 54.0 54.1

Spencer TJ, Brown A, Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N, Lomedico A, Faraone SV, Biederman J. Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies. J. Clin. Psychiatry. September 2013, 74 (9): 902–917. PMC 3801446

. PMID 24107764. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08287.

. PMID 24107764. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08287.

- ^ 55.0 55.1

Frodl T, Skokauskas N. Meta-analysis of structural MRI studies in children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder indicates treatment effects.. Acta psychiatrica Scand. February 2012, 125 (2): 114–126. PMID 22118249. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01786.x.

Basal ganglia regions like the right globus pallidus, the right putamen, and the nucleus caudatus are structurally affected in children with ADHD. These changes and alterations in limbic regions like ACC and amygdala are more pronounced in non-treated populations and seem to diminish over time from child to adulthood. Treatment seems to have positive effects on brain structure.

- ^ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3

Millichap JG. Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD. Millichap JG (编). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD 2nd. New York, USA: Springer. 2010: 121–123, 125–127. ISBN 9781441913968.

Ongoing research has provided answers to many of the parents’ concerns, and has confirmed the effectiveness and safety of the long-term use of medication.

- ^ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 Arnold LE, Hodgkins P, Caci H, Kahle J, Young S. Effect of treatment modality on long-term outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. February 2015, 10 (2): e0116407. PMC 4340791

. PMID 25714373. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116407.

. PMID 25714373. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116407. The highest proportion of improved outcomes was reported with combination treatment (83% of outcomes). Among significantly improved outcomes, the largest effect sizes were found for combination treatment. The greatest improvements were associated with academic, self-esteem, or social function outcomes.

Figure 3: Treatment benefit by treatment type and outcome group - ^ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 58.4 Huang YS, Tsai MH. Long-term outcomes with medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: current status of knowledge. CNS Drugs. July 2011, 25 (7): 539–554. PMID 21699268. doi:10.2165/11589380-000000000-00000.

Recent studies have demonstrated that stimulants, along with the non-stimulants atomoxetine and extended-release guanfacine, are continuously effective for more than 2-year treatment periods with few and tolerable adverse effects. The effectiveness of long-term therapy includes not only the core symptoms of ADHD, but also improved quality of life and academic achievements. The most concerning short-term adverse effects of stimulants, such as elevated blood pressure and heart rate, waned in long-term follow-up studies. ... In the longest follow-up study (of more than 10 years), lifetime stimulant treatment for ADHD was effective and protective against the development of adverse psychiatric disorders.

- ^ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 154–157. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 Bidwell LC, McClernon FJ, Kollins SH. Cognitive enhancers for the treatment of ADHD. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. August 2011, 99 (2): 262–274. PMC 3353150

. PMID 21596055. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.002.

. PMID 21596055. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.002.

- ^

Parker J, Wales G, Chalhoub N, Harpin V. The long-term outcomes of interventions for the management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. (systematic review (secondary source)). September 2013, 6: 87–99. PMC 3785407

. PMID 24082796. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S49114.

. PMID 24082796. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S49114. Only one paper53 examining outcomes beyond 36 months met the review criteria. ... There is high level evidence suggesting that pharmacological treatment can have a major beneficial effect on the core symptoms of ADHD (hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity) in approximately 80% of cases compared with placebo controls, in the short term.

- ^ Millichap JG. Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD. Millichap JG (编). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD 2nd. New York, USA: Springer. 2010: 111–113. ISBN 9781441913968.

- ^ Stimulants for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. WebMD. Healthwise. 2010-04-12 [2013-11-12].

- ^ Scholten RJ, Clarke M, Hetherington J. The Cochrane Collaboration. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. August 2005,. 59 Suppl 1: S147–S149; discussion S195–S196. PMID 16052183. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602188.

- ^ Castells X, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Bosch R, Nogueira M, Casas M. Castells X , 编. Amphetamines for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. June 2011, (6): CD007813. PMID 21678370. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007813.pub2.

- ^ Punja S, Shamseer L, Hartling L, Urichuk L, Vandermeer B, Nikles J, Vohra S. Amphetamines for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. February 2016, 2: CD009996. PMID 26844979. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009996.pub2.

- ^ Pringsheim T, Steeves T. Pringsheim T , 编. Pharmacological treatment for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children with comorbid tic disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. April 2011, (4): CD007990. PMID 21491404. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007990.pub2.

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

medlineplus1的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Abuse, National Institute on Drug. Stimulant ADHD Medications: Methylphenidate and Amphetamines.

- ^ Choices, N. H. S. What is a controlled medicine (drug)? - Health questions - NHS Choices. 2016-12-12.

- ^ Methylphenidate. Home of MedlinePlus → Drugs, Herbs and Supplements → Methylphenidate Methylphenidate pronounced as (meth il fen i date). 2016-02-15 [February twenty seventh, 2017].

- ^ Combining medications could offer better results for ADHD patients. Science News. Elsevier. 2016-08-01 [January 2017]. (原始内容存档于August 2016).

"Three studies to be published in the August 2016 issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (JAACAP) report that combining two standard medications could lead to greater clinical improvements for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than either ADHD therapy alone.", August, 2016

- ^ Adults with ADHD. MedlinePlus the Magazine 9. 8600 Rockville Pike • Bethesda, MD 20894, United States of America: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE at the NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH. Spring 2014: 19. ISSN 1937-4712 (美国英语).

- ^ Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Home → Medical Encyclopedia → Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE at the NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH. 2016-05-25 [February twenty seventh, 2017.].

- ^ All Disorders. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. [February twenty seventh, 2017].

- ^

Bagot KS, Kaminer Y. Efficacy of stimulants for cognitive enhancement in non-attention deficit hyperactivity disorder youth: a systematic review. Addiction. April 2014, 109 (4): 547–557. PMC 4471173

. PMID 24749160. doi:10.1111/add.12460.

. PMID 24749160. doi:10.1111/add.12460. Amphetamine has been shown to improve consolidation of information (0.02 ≥ P ≤ 0.05), leading to improved recall.

- ^ Devous MD, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ. Regional cerebral blood flow response to oral amphetamine challenge in healthy volunteers. J. Nucl. Med. April 2001, 42 (4): 535–542. PMID 11337538.

- ^

Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 10: Neural and Neuroendocrine Control of the Internal Milieu. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 266. ISBN 9780071481274.

Dopamine acts in the nucleus accumbens to attach motivational significance to stimuli associated with reward.

- ^ 79.0 79.1 79.2 Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG. Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation. Pharmacol. Rev. January 2014, 66 (1): 193–221. PMID 24344115. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054.

- ^ Twohey M. Pills become an addictive study aid. JS Online. 2006-03-26 [2007-12-02]. (原始内容存档于2007-08-15).

- ^ 81.0 81.1 81.2 81.3

Parr JW. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the athlete: new advances and understanding. Clin. Sports Med. July 2011, 30 (3): 591–610. PMID 21658550. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2011.03.007.

In 1980, Chandler and Blair47 showed significant increases in knee extension strength, acceleration, anaerobic capacity, time to exhaustion during exercise, pre-exercise and maximum heart rates, and time to exhaustion during maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) testing after administration of 15 mg of dextroamphetamine versus placebo. Most of the information to answer this question has been obtained in the past decade through studies of fatigue rather than an attempt to systematically investigate the effect of ADHD drugs on exercise.

- ^ 82.0 82.1 82.2

Roelands B, de Koning J, Foster C, Hettinga F, Meeusen R. Neurophysiological determinants of theoretical concepts and mechanisms involved in pacing. Sports Med. May 2013, 43 (5): 301–311. PMID 23456493. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0030-4.

In high-ambient temperatures, dopaminergic manipulations clearly improve performance. The distribution of the power output reveals that after dopamine reuptake inhibition, subjects are able to maintain a higher power output compared with placebo. ... Dopaminergic drugs appear to override a safety switch and allow athletes to use a reserve capacity that is ‘off-limits’ in a normal (placebo) situation.

- ^ Bracken NM. National Study of Substance Use Trends Among NCAA College Student-Athletes (PDF). NCAA Publications. National Collegiate Athletic Association. January 2012 [2013-10-08].

- ^

Docherty JR. Pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Br. J. Pharmacol. June 2008, 154 (3): 606–622. PMC 2439527

. PMID 18500382. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124.

. PMID 18500382. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124.

- ^

Parker KL, Lamichhane D, Caetano MS, Narayanan NS. Executive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease and timing deficits. Front. Integr. Neurosci. October 2013, 7: 75. PMC 3813949

. PMID 24198770. doi:10.3389/fnint.2013.00075.

. PMID 24198770. doi:10.3389/fnint.2013.00075. Manipulations of dopaminergic signaling profoundly influence interval timing, leading to the hypothesis that dopamine influences internal pacemaker, or “clock,” activity. For instance, amphetamine, which increases concentrations of dopamine at the synaptic cleft advances the start of responding during interval timing, whereas antagonists of D2 type dopamine receptors typically slow timing;... Depletion of dopamine in healthy volunteers impairs timing, while amphetamine releases synaptic dopamine and speeds up timing.

- ^

Rattray B, Argus C, Martin K, Northey J, Driller M. Is it time to turn our attention toward central mechanisms for post-exertional recovery strategies and performance?. Front. Physiol. March 2015, 6: 79. PMC 4362407

. PMID 25852568. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00079.

. PMID 25852568. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00079. Aside from accounting for the reduced performance of mentally fatigued participants, this model rationalizes the reduced RPE and hence improved cycling time trial performance of athletes using a glucose mouthwash (Chambers et al., 2009) and the greater power output during a RPE matched cycling time trial following amphetamine ingestion (Swart, 2009). ... Dopamine stimulating drugs are known to enhance aspects of exercise performance (Roelands et al., 2008)

- ^

Roelands B, De Pauw K, Meeusen R. Neurophysiological effects of exercise in the heat. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. June 2015,. 25 Suppl 1: 65–78. PMID 25943657. doi:10.1111/sms.12350.

This indicates that subjects did not feel they were producing more power and consequently more heat. The authors concluded that the “safety switch” or the mechanisms existing in the body to prevent harmful effects are overridden by the drug administration (Roelands et al., 2008b). Taken together, these data indicate strong ergogenic effects of an increased DA concentration in the brain, without any change in the perception of effort.

- ^

Kessler S. Drug therapy in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. South. Med. J. January 1996, 89 (1): 33–38. PMID 8545689. doi:10.1097/00007611-199601000-00005.

statements on package inserts are not intended to limit medical practice. Rather they are intended to limit claims by pharmaceutical companies. ... the FDA asserts explicitly, and the courts have upheld that clinical decisions are to be made by physicians and patients in individual situations.

- ^ 89.0 89.1 89.2 89.3 89.4 89.5 89.6 Adderall XR Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc: 4–6. December 2013 [2013-12-30].

- ^ 90.00 90.01 90.02 90.03 90.04 90.05 90.06 90.07 90.08 90.09 Heedes G, Ailakis J. Amphetamine (PIM 934). INCHEM. International Programme on Chemical Safety. [2014-06-24].

- ^ 91.0 91.1 Dexedrine Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Amedra Pharmaceuticals LLC. October 2013 [2013-11-04].

- ^

Feinberg SS. Combining stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review of uses and one possible additional indication. J. Clin. Psychiatry. November 2004, 65 (11): 1520–1524. \ PMID 15554766 \ 请检查

|pmid=值 (帮助). doi:10.4088/jcp.v65n1113. - ^ Stewart JW, Deliyannides DA, McGrath PJ. How treatable is refractory depression?. J. Affect. Disord. June 2014, 167: 148–152. PMID 24972362. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.047.

- ^ 94.0 94.1 引用错误:没有为名为

pmid18295156的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 95.0 95.1 Spiller HA, Hays HL, Aleguas A. Overdose of drugs for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: clinical presentation, mechanisms of toxicity, and management. CNS Drugs. June 2013, 27 (7): 531–543. PMID 23757186. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0084-8.

Amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methylphenidate act as substrates for the cellular monoamine transporter, especially the dopamine transporter (DAT) and less so the norepinephrine (NET) and serotonin transporter. The mechanism of toxicity is primarily related to excessive extracellular dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin.

- ^ Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 (PDF). Lancet. 2015, 385 (9963): 117–171 [2015-03-03]. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. Amphetamine use disorders ... 3,788 (3,425–4,145)

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories. Amphetamine – Homo sapiens (human). KEGG Pathway. 2014-10-10 [2014-10-31].

- ^ 98.0 98.1 98.2 98.3 98.4 98.5 Nechifor M. Magnesium in drug dependences. Magnes. Res. March 2008, 21 (1): 5–15. PMID 18557129.

- ^ 99.0 99.1 99.2 99.3 99.4 Ruffle JK. Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. November 2014, 40 (6): 428–437. PMID 25083822. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840.

ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure.

- ^ 100.0 100.1 100.2 100.3 100.4 Nestler, Eric J. Cellular basis of memory for addiction. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2013-12, 15 (4): 431–443. ISSN 1294-8322. PMC 3898681

. PMID 24459410. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler.

. PMID 24459410. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler.

- ^ Robison AJ, Nestler EJ. Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. November 2011, 12 (11): 623–637. PMC 3272277

. PMID 21989194. doi:10.1038/nrn3111.

. PMID 21989194. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity.

- ^ 102.00 102.01 102.02 102.03 102.04 102.05 102.06 102.07 102.08 102.09 102.10 102.11 102.12 102.13 102.14 102.15 102.16 102.17 102.18 102.19 102.20 102.21 Olsen CM. Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions. Neuropharmacology. December 2011, 61 (7): 1109–1122. PMC 3139704

. PMID 21459101. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010.

. PMID 21459101. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. Similar to environmental enrichment, studies have found that exercise reduces self-administration and relapse to drugs of abuse (Cosgrove et al., 2002; Zlebnik et al., 2010). There is also some evidence that these preclinical findings translate to human populations, as exercise reduces withdrawal symptoms and relapse in abstinent smokers (Daniel et al., 2006; Prochaska et al., 2008), and one drug recovery program has seen success in participants that train for and compete in a marathon as part of the program (Butler, 2005). ... In humans, the role of dopamine signaling in incentive-sensitization processes has recently been highlighted by the observation of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs. This syndrome is characterized by a medication-induced increase in (or compulsive) engagement in non-drug rewards such as gambling, shopping, or sex (Evans et al., 2006; Aiken, 2007; Lader, 2008).

- ^ 103.0 103.1 103.2 103.3 Lynch WJ, Peterson AB, Sanchez V, Abel J, Smith MA. Exercise as a novel treatment for drug addiction: a neurobiological and stage-dependent hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. September 2013, 37 (8): 1622–1644. PMC 3788047

. PMID 23806439. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.011.

. PMID 23806439. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.011. These findings suggest that exercise may “magnitude”-dependently prevent the development of an addicted phenotype possibly by blocking/reversing behavioral and neuroadaptive changes that develop during and following extended access to the drug. ... Exercise has been proposed as a treatment for drug addiction that may reduce drug craving and risk of relapse. Although few clinical studies have investigated the efficacy of exercise for preventing relapse, the few studies that have been conducted generally report a reduction in drug craving and better treatment outcomes ... Taken together, these data suggest that the potential benefits of exercise during relapse, particularly for relapse to psychostimulants, may be mediated via chromatin remodeling and possibly lead to greater treatment outcomes.

- ^ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Zhou Y, Zhao M, Zhou C, Li R. Sex differences in drug addiction and response to exercise intervention: From human to animal studies. Front. Neuroendocrinol. July 2015, 40: 24–41. PMID 26182835. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2015.07.001.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that exercise may serve as a substitute or competition for drug abuse by changing ΔFosB or cFos immunoreactivity in the reward system to protect against later or previous drug use. ... The postulate that exercise serves as an ideal intervention for drug addiction has been widely recognized and used in human and animal rehabilitation.

- ^ 105.0 105.1 105.2 Linke SE, Ussher M. Exercise-based treatments for substance use disorders: evidence, theory, and practicality. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. January 2015, 41 (1): 7–15. PMC 4831948

. PMID 25397661. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.976708.

. PMID 25397661. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.976708. The limited research conducted suggests that exercise may be an effective adjunctive treatment for SUDs. In contrast to the scarce intervention trials to date, a relative abundance of literature on the theoretical and practical reasons supporting the investigation of this topic has been published. ... numerous theoretical and practical reasons support exercise-based treatments for SUDs, including psychological, behavioral, neurobiological, nearly universal safety profile, and overall positive health effects.

- ^ 106.0 106.1 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 386. ISBN 9780071481274.

Currently, cognitive–behavioral therapies are the most successful treatment available for preventing the relapse of psychostimulant use.

- ^ Albertson TE. Amphetamines. Olson KR, Anderson IB, Benowitz NL, Blanc PD, Kearney TE, Kim-Katz SY, Wu AH (编). Poisoning & Drug Overdose 6th. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2011: 77–79. ISBN 9780071668330.

- ^ Nestler, Eric J.; Malenka, Robert C. Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders. Molecular neuropharmacology : a foundation for clinical neuroscience 2nd. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 364–375. ISBN 978-0-07-164119-7. OCLC 273018757.

- ^ Glossary. Icahn School of Medicine. [2021-04-29].

- ^ Volkow, Nora D.; Koob, George F.; McLellan, A. Thomas. Longo, Dan L. , 编. Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016-01-28, 374 (4): 363–371. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 6135257

. PMID 26816013. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480 (英语).

. PMID 26816013. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480 (英语).

- ^ Amphetamines: Drug Use and Abuse. Merck Manual Home Edition. Merck. February 2003 [2007-02-28]. (原始内容存档于2007-02-17).

- ^ Perez-Mana C, Castells X, Torrens M, Capella D, Farre M. Pérez-Mañá C , 编. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for amphetamine abuse or dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. September 2013, 9: CD009695. PMID 23996457. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009695.pub2.

- ^ Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. July 2006, 29: 565–598. PMID 16776597. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009.

- ^ 114.0 114.1 114.2 114.3 114.4 114.5 114.6 114.7 Robison AJ, Nestler EJ. Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. November 2011, 12 (11): 623–637. PMC 3272277

. PMID 21989194. doi:10.1038/nrn3111.

. PMID 21989194. doi:10.1038/nrn3111.

- ^ 115.0 115.1 115.2 115.3 115.4 Steiner H, Van Waes V. Addiction-related gene regulation: risks of exposure to cognitive enhancers vs. other psychostimulants. Prog. Neurobiol. January 2013, 100: 60–80. PMC 3525776

. PMID 23085425. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.10.001.

. PMID 23085425. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.10.001.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 4: Signal Transduction in the Brain. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 94. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories. Alcoholism – Homo sapiens (human). KEGG Pathway. 2014-10-29 [2014-10-31].

- ^ Kim Y, Teylan MA, Baron M, Sands A, Nairn AC, Greengard P. Methylphenidate-induced dendritic spine formation and DeltaFosB expression in nucleus accumbens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. February 2009, 106 (8): 2915–2920. PMC 2650365

. PMID 19202072. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813179106.

. PMID 19202072. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813179106.

- ^ Nestler EJ. Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction. Neuropharmacology. January 2014,. 76 Pt B: 259–268. PMC 3766384

. PMID 23643695. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.004.

. PMID 23643695. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.004.

- ^ 120.0 120.1 Blum K, Werner T, Carnes S, Carnes P, Bowirrat A, Giordano J, Oscar-Berman M, Gold M. Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms. J. Psychoactive Drugs. March 2012, 44 (1): 38–55. PMC 4040958

. PMID 22641964. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.662112.

. PMID 22641964. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.662112.

- ^ Pitchers KK, Vialou V, Nestler EJ, Laviolette SR, Lehman MN, Coolen LM. Natural and drug rewards act on common neural plasticity mechanisms with ΔFosB as a key mediator. J. Neurosci. February 2013, 33 (8): 3434–3442. PMC 3865508

. PMID 23426671. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4881-12.2013.

. PMID 23426671. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4881-12.2013.

- ^ Beloate LN, Weems PW, Casey GR, Webb IC, Coolen LM. Nucleus accumbens NMDA receptor activation regulates amphetamine cross-sensitization and deltaFosB expression following sexual experience in male rats. Neuropharmacology. February 2016, 101: 154–164. PMID 26391065. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.023.

- ^ Stoops WW, Rush CR. Combination pharmacotherapies for stimulant use disorder: a review of clinical findings and recommendations for future research. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. May 2014, 7 (3): 363–374. PMC 4017926

. PMID 24716825. doi:10.1586/17512433.2014.909283.

. PMID 24716825. doi:10.1586/17512433.2014.909283. Despite concerted efforts to identify a pharmacotherapy for managing stimulant use disorders, no widely effective medications have been approved.

- ^ Perez-Mana C, Castells X, Torrens M, Capella D, Farre M. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for amphetamine abuse or dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. September 2013, 9: CD009695. PMID 23996457. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009695.pub2.

To date, no pharmacological treatment has been approved for [addiction], and psychotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment. ... Results of this review do not support the use of psychostimulant medications at the tested doses as a replacement therapy

- ^ Forray A, Sofuoglu M. Future pharmacological treatments for substance use disorders. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. February 2014, 77 (2): 382–400. PMC 4014020

. PMID 23039267. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04474.x.

. PMID 23039267. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04474.x.

- ^ 126.0 126.1 Jing L, Li JX. Trace amine-associated receptor 1: A promising target for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction. Eur. J. Pharmacol. August 2015, 761: 345–352. PMC 4532615

. PMID 26092759. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.019.

. PMID 26092759. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.019. Existing data provided robust preclinical evidence supporting the development of TAAR1 agonists as potential treatment for psychostimulant abuse and addiction.

- ^ 127.0 127.1 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 5: Excitatory and Inhibitory Amino Acids. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 124–125. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ 128.0 128.1 128.2 Carroll ME, Smethells JR. Sex Differences in Behavioral Dyscontrol: Role in Drug Addiction and Novel Treatments. Front. Psychiatry. February 2016, 6: 175. PMC 4745113

. PMID 26903885. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00175.

. PMID 26903885. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00175. Physical Exercise

There is accelerating evidence that physical exercise is a useful treatment for preventing and reducing drug addiction ... In some individuals, exercise has its own rewarding effects, and a behavioral economic interaction may occur, such that physical and social rewards of exercise can substitute for the rewarding effects of drug abuse. ... The value of this form of treatment for drug addiction in laboratory animals and humans is that exercise, if it can substitute for the rewarding effects of drugs, could be self-maintained over an extended period of time. Work to date in [laboratory animals and humans] regarding exercise as a treatment for drug addiction supports this hypothesis. ... Animal and human research on physical exercise as a treatment for stimulant addiction indicates that this is one of the most promising treatments on the horizon. - ^ 129.0 129.1 129.2 129.3 Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Heinzerling K, Ling W. Shoptaw SJ , 编. Treatment for amphetamine withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. April 2009, (2): CD003021. PMID 19370579. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003021.pub2.

- ^ Adderall IR Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. October 2015 [2016-05-18].

- ^ Adderall XR Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc. December 2013 [2013-12-30].

- ^ Advokat C. Update on amphetamine neurotoxicity and its relevance to the treatment of ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. July 2007, 11 (1): 8–16. PMID 17606768. doi:10.1177/1087054706295605.

- ^ 133.0 133.1 133.2 133.3 Bowyer JF, Hanig JP. Amphetamine- and methamphetamine-induced hyperthermia: Implications of the effects produced in brain vasculature and peripheral organs to forebrain neurotoxicity. Temperature (Austin). November 2014, 1 (3): 172–182. PMC 5008711

. PMID 27626044. doi:10.4161/23328940.2014.982049.

. PMID 27626044. doi:10.4161/23328940.2014.982049. Hyperthermia alone does not produce amphetamine-like neurotoxicity but AMPH and METH exposures that do not produce hyperthermia (≥40°C) are minimally neurotoxic. Hyperthermia likely enhances AMPH and METH neurotoxicity directly through disruption of protein function, ion channels and enhanced ROS production. ... The hyperthermia and the hypertension produced by high doses amphetamines are a primary cause of transient breakdowns in the blood-brain barrier (BBB) resulting in concomitant regional neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in laboratory animals. ... In animal models that evaluate the neurotoxicity of AMPH and METH, it is quite clear that hyperthermia is one of the essential components necessary for the production of histological signs of dopamine terminal damage and neurodegeneration in cortex, striatum, thalamus and hippocampus.

- ^ Amphetamine. Hazardous Substances Data Bank. United States National Library of Medicine – Toxicology Data Network. [2014-02-26].

Direct toxic damage to vessels seems unlikely because of the dilution that occurs before the drug reaches the cerebral circulation.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 15: Reinforcement and addictive disorders. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 370. ISBN 9780071481274.

Unlike cocaine and amphetamine, methamphetamine is directly toxic to midbrain dopamine neurons.

- ^ Sulzer D, Zecca L. Intraneuronal dopamine-quinone synthesis: a review. Neurotox. Res. February 2000, 1 (3): 181–195. PMID 12835101. doi:10.1007/BF03033289.

- ^ Miyazaki I, Asanuma M. Dopaminergic neuron-specific oxidative stress caused by dopamine itself (PDF). Acta Med. Okayama. June 2008, 62 (3): 141–150. PMID 18596830.