Gene Roddenberry: Difference between revisions

Makecat-bot (talk | contribs) m r2.7.3) (Robot: Adding ka:ჯინ როდენბერი |

Changed "Genesis" to its proper title "Genesis II" |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American screenwriter and producer (1921–1991)}} |

|||

{{redirect|Eugene Roddenberry|Roddenberry's son|Eugene Roddenberry Jr.}} |

|||

{{good article}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2022}} |

|||

{{Infobox person |

{{Infobox person |

||

| name = Gene Roddenberry |

| name = Gene Roddenberry |

||

| image = Gene |

| image = Gene Roddenberry crop.jpg |

||

| caption = Roddenberry with [[Space Shuttle Enterprise|Space Shuttle ''Enterprise'']] in [[Palmdale, California]], 1976 |

|||

| imagesize = 200px |

|||

| caption = Roddenberry in 1976 |

|||

| birth_name = Eugene Wesley Roddenberry |

| birth_name = Eugene Wesley Roddenberry |

||

| birth_date = {{ |

| birth_date = {{birth date|mf=yes|1921|8|19}} |

||

| birth_place = [[El Paso, Texas]], U.S. |

| birth_place = [[El Paso, Texas]], U.S. |

||

| death_date = {{ |

| death_date = {{death date and age|1991|10|24|1921|8|19}} |

||

| death_cause = Heart failure |

|||

<!--''Incorrect info - see talk page'': |resting_place = [[Outer space]] --> |

|||

| death_place = [[Santa Monica, California]], U.S. |

| death_place = [[Santa Monica, California]], U.S. |

||

| other_names = Robert Wesley |

| other_names = Robert Wesley |

||

| notable_works = ''[[Star Trek]]'', ''[[Star Trek: The Next Generation]]'' |

|||

| nationality = American |

|||

| education = [[Franklin High School (Los Angeles)|Franklin High School]] |

|||

| alma_mater = [[Los Angeles City College]] |

| alma_mater = [[Los Angeles City College]] |

||

| |

| awards = [[Hollywood Walk of Fame]] |

||

| occupation = {{cslist|Television writer|producer}} |

|||

| residence = Bel Air, Los Angeles, California |

|||

| spouse = {{plainlist| |

|||

| occupation = [[Television writer]], [[Television producer|producer]] and [[futurist]] |

|||

* {{marriage|Eileen-Anita Rexroat|June 20, 1942|1969|end=divorced}} |

|||

| spouse = Eileen-Anita Rexroat (1942–69)<br />[[Majel Barrett]] (1969–91, his death) |

|||

* {{marriage|[[Majel Barrett]]|1969|<!-- Omission per Template:Marriage instructions -->}} |

|||

| children = 2 daughters<br>[[Rod Roddenberry]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| partner = [[Susan Sackett]] (1975–1991; his death) |

|||

'''Eugene Wesley "Gene" Roddenberry''' (August 19, 1921 – October 24, 1991) was an American television screenwriter and producer. He was best known for creating the American science fiction series ''[[Star Trek]]''. Born in [[El Paso, Texas]], Roddenberry grew up in [[Los Angeles|Los Angeles, California]] where his father worked as a police officer. Roddenberry flew 89 combat missions in the [[United States Army Air Forces]] during [[World War II]], and worked as a commercial pilot after the war. He later followed in his father's footsteps, joining the [[Los Angeles Police Department]] to provide for his family, but began focusing on writing scripts for television. |

|||

| children = 3, including [[Rod Roddenberry|Rod]] |

|||

As a freelance writer, Roddenberry wrote scripts for ''[[Highway Patrol (TV series)|Highway Patrol]]'', ''[[Have Gun–Will Travel]]'', and other series, before creating and producing his own television program, ''[[The Lieutenant]]''. In 1964, Roddenberry created ''Star Trek'', which premiered in 1966 and ran for three seasons before being canceled. Syndication of ''Star Trek'' led to increasing popularity, and Roddenberry continued to create, produce, and consult on [[Star Trek (film series)|''Star Trek'' films]] and the television series, ''[[Star Trek: The Next Generation]]'' until his death. Roddenberry received a star on the [[Hollywood Walk of Fame]] and he was inducted into the [[Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame|Science Fiction Hall of Fame]] and the [[Academy of Television Arts & Sciences]]' Hall of Fame. Years after his death, Roddenberry was one of the first humans to have his ashes [[space burial|"buried" in outer space]]. |

|||

The ''Star Trek'' franchise Roddenberry created has produced material for over four decades, producing six television series, 726 episodes and eleven films, with a twelfth film currently in post-production and scheduled for a May 2013 release. Additionally, the popularity of the ''Star Trek'' universe and films inspired the gentle parody/homage film ''[[Galaxy Quest]]'' (1999), as well as many books, video games and [[Star Trek fan productions|fan films]] set in the various "eras" of the ''Star Trek'' universe. |

|||

==Early life (1921–1941)== |

|||

Gene Roddenberry was born on August 19, 1921, in [[El Paso, Texas]],<ref name="SpaceSciences">{{cite book |year=2002 |chapter=Gene Roddenberry |title=Space Sciences (Macmillan Science Library) |publisher=Gale |isbn=0-02-865546-X}}</ref> His parents were police officer Eugene Edward Roddenberry and Caroline "Glen" (née Golemon) Roddenberry.<ref name="museum.tv">[http://www.museum.tv/archives/etv/R/htmlR/roddenberry/roddenberry.htm RODDENBERRY, GENE - The Museum of Broadcast Communications<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> He grew up in Los Angeles and attended Berendo Junior High School (now Berendo Middle School) before graduating from [[Franklin High School (Los Angeles, California)|Franklin High School]] in the winter of 1939; he subsequently entered [[Los Angeles City College]] that February. |

|||

Although Roddenberry ranked at or above the ninetieth percentile in an [[intelligence test]] administered as part of his college entrance examination, he elected to "[stay] true to his roots" and major in the "solidly [[blue collar]]" [[police science]] curriculum; as president of the school's Police Club, he liaised with the [[Federal Bureau of Investigation]].<ref>Alexander, David, "Star Trek Creator", ROC Books, an imprint of Dutton Signet, a division of Penguin Books USA, New York, June 1994, ISBN 0-451-54518-9 {{Please check ISBN|reason=Check digit (9) does not correspond to calculated figure.}}, pp. 47-48.</ref> He also developed an interest in [[aeronautical engineering]] and obtained a [[pilot licensing and certification|pilot's license]] through the [[United States Army Air Corps]]-sponsored Civilian Pilot Training program.<ref>Alexander, David, "Star Trek Creator", ROC Books, an imprint of Dutton Signet, a division of Penguin Books USA, New York, June 1994, ISBN 0-451-54518-9 {{Please check ISBN|reason=Check digit (9) does not correspond to calculated figure.}}, pp. 49-50.</ref> He graduated from Los Angeles City College with an [[Associate of Arts]] degree in police science in 1941, becoming the first member of his family to earn a [[college degree]].<ref>Alexander, David, "Star Trek Creator", ROC Books, an imprint of Dutton Signet, a division of Penguin Books USA, New York, June 1994, ISBN 0-451-54518-9 {{Please check ISBN|reason=Check digit (9) does not correspond to calculated figure.}}, pp. 52.</ref> |

|||

==Military service and civil aviation (1941-1949)== |

|||

In 1941, he joined the [[United States Army Air Corps]], which in the same year became the [[United States Army Air Forces]]. He began training at Goodfellow Field (now [[Goodfellow Air Force Base]]) in [[San Angelo, Texas]] with other Civilian Pilot Training alums and graduated as a [[second lieutenant]] in September 1942, Class G.<ref name="Undergraduate Pilot Training Yearbook">{{cite book|title=CAVU Forty-Two G|year=1942|publisher=Class 42-G, US Army Air Corps|location=Goodfellow Field, San Angelo, TX|pages=70|url=http://aafcollection.info/items/documents/view.php?file=000105-01-00.pdf}}</ref> He flew combat missions in the [[Pacific Theater of Operations|Pacific Theatre]] with the "Bomber Barons" of the [[394th Bomb Squadron]], [[5th Bombardment Group]] of the [[Thirteenth Air Force]] and on August 2, 1943, Roddenberry was piloting a [[B-17 Flying Fortress|B-17E Flying Fortress]] named the "Yankee Doodle", from [[Espiritu Santo|Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides]], when mechanical failure caused it to crash on take-off. In total, he flew eighty-nine missions for which he was awarded the [[Distinguished Flying Cross (U.S.)|Distinguished Flying Cross]] and the [[Air Medal]] before being honorably discharged at the rank of [[Captain (United States)|captain]] in July 1945.<ref>Freeman, Roger A., with Osborne, David., "The B-17 Flying Fortress Story", Arms & Armour Press, Wellington House, London, UK, 1998, ISBN 1-85409-301-0, p. 74.</ref><ref>Alexander, David, "Star Trek Creator", ROC Books, an imprint of Dutton Signet, a division of Penguin Books USA, New York, June 1994, ISBN 0-451-54518-9 {{Please check ISBN|reason=Check digit (9) does not correspond to calculated figure.}}, pp. 75-76.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.smdc-armyforces.army.mil/Pic_Archive/ASJ_PDFs/ASJ_VOL_3_NO_1_Y_FLIP_1.pdf|accessdate=December 21, 2008|author=Edward B. Kiker|format=PDF|title=SOLDIERS OF VISION: We Don’t Stop When We Take off the Uniform|date=Winter/Spring 2004|publisher=Army Space Journal|quote=He took part in 89 missions and sorties, and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal.}}</ref> |

|||

While working on ''Star Trek'', Roddenberry would spend much of his spare time at California's Monterey Peninsula Airport with a group of aviation enthusiasts who flew World War II fighters. |

|||

After the military, Roddenberry worked as a commercial pilot for [[Pan American World Airways]]. He received a Civil Aeronautics commendation for his rescue efforts following a June 1947 crash in the Syrian desert while on a flight to [[Istanbul]] from [[Karachi]]. While based out of [[Miami]], Roddenberry enrolled in three writing classes at the [[University of Miami]], from which he withdrew with passing grades following his transfer to [[New York City]] in November 1945. During his New York-area sojourn, the Roddenberrys lived in [[Jamaica, Queens]] and [[River Edge, New Jersey]]. He briefly continued his education, taking four writing courses offered by the [[Columbia University School of General Studies]] in the spring and fall of 1946 before withdrawing due to the demands of his employment in January 1947. |

|||

==Los Angeles Police Department (1949–1956)== |

|||

{{Infobox police officer |

|||

|name = Gene Roddenberry |

|||

|image = |

|||

|caption = |

|||

|birth_date = {{Birth date|1921|8|19}} |

|||

|death_date = {{Death date and age|1991|10|24|1921|8|19}} |

|||

|badgenumber = |

|||

|birth_place = [[El Paso, Texas]] |

|||

|nickname = |

|||

|department = [[Los Angeles Police Department]] |

|||

|service = United States |

|||

|serviceyears = 1949–1956 |

|||

|rank = Sworn in as an Officer – 1949;<br>[[File:LAPD Police Officer-3.jpg|20px]] Police Officer III – 1951;<br />[[File:LAPD Sergeant-1.jpg|20px]] Sergeant I – 1953. |

|||

|relations = Eileen-Anita Rexroat (wife) |

|||

|laterwork = LAPD speechwriter, screenwriter, dramatist, television producer, creator of [[Star Trek]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Eugene Wesley Roddenberry Sr.''' (August 19, 1921 – October 24, 1991) was an American television screenwriter and producer who created the science fiction series and fictional universe ''[[Star Trek]].'' Born in [[El Paso, Texas]], Roddenberry grew up in Los Angeles, where his father was a police officer. Roddenberry flew 89 combat missions in the [[United States Army Air Forces|Army Air Forces]] during [[World War II]] and worked as a commercial pilot after the war. Later, he joined the [[Los Angeles Police Department]] and began to write for television. |

|||

Pursuing a career in Hollywood, Roddenberry left Pan Am in 1949 and returned to Los Angeles. To provide for his family, he joined the [[Los Angeles Police Department]] on February 1, 1949. He became a police officer III in 1951 and was made a Sergeant in 1953.<ref>David Alexander.(1994) "Star Trek Creator : The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry," Roc, p. 104.</ref> Toward the end of his Law enforcement career as a sergeant he became the speech writer for legendary LAPD Chief [[William H. Parker (police officer)|William H. Parker]]. He reputedly based his iconic ''Star Trek'' character [[Mr. Spock]] on Parker for his very rational and low emotional behavior.<ref>[http://www.latimesmagazine.com/2010/04/shadow-caster.html ''Shadow Caster: William H. Parker and Mickey Cohen’s L.A. cops-and-robbers tale is way stranger than fiction'' by John Buntin ''LA Times Magazine'' April 2010]</ref> On June 7, 1956, he resigned from the police force to concentrate on his writing career.<ref name="Alexander, p.141">Alexander, p. 141.</ref> In his brief letter of resignation, Roddenberry wrote: |

|||

<blockquote>I find myself unable to support my family at present on anticipated police salary levels in a manner we consider necessary. Having spent slightly more than seven years on this job, during all of which fair treatment and enjoyable working conditions were received, this decision is made with considerable and genuine regret.<ref name="Alexander, p.141"/></blockquote> |

|||

As a [[freelance writer]], Roddenberry wrote scripts for ''[[Highway Patrol (American TV series)|Highway Patrol]]'', ''[[Have Gun – Will Travel]]'', and other series, before creating and producing his own television series, ''[[The Lieutenant]].'' In 1964, Roddenberry created the original ''[[Star Trek: The Original Series|Star Trek]]'' series, which premiered in 1966 and ran for three seasons. He then worked on projects including a string of failed television pilots. The syndication of ''Star Trek'' led to its growing popularity, resulting in the [[Star Trek (film series)|''Star Trek'' feature films]], which Roddenberry continued to produce and consult on. In 1987, the sequel series ''[[Star Trek: The Next Generation]]'' began airing on television in [[first-run syndication]]; Roddenberry was involved in the initial development but took a less active role after the first season due to ill health. He consulted on the series until his death in 1991. |

|||

==Television and film career (1955–1991)== |

|||

While Roddenberry worked for the LAPD, he wrote television scripts under the pseudonym "Robert Wesley" for the series ''[[Highway Patrol (TV series)|Highway Patrol]]'' and both the TV and radio versions of ''[[Have Gun–Will Travel]]''. In 1957, he wrote an episode for the ''[[Boots and Saddles (TV series)|Boots and Saddles]]'' [[Western (genre)|western]] series entitled "The Prussian Farmer". In 1960, he wrote four episodes of the British ([[ITC Entertainment]]) made Australian western ''[[Whiplash (TV series)|Whiplash]]''. |

|||

In 1985, Roddenberry became the first TV writer with a star on the [[Hollywood Walk of Fame]]. He was later inducted into the [[EMP Museum#Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame|Science Fiction Hall of Fame]] and the [[Academy of Television Arts & Sciences]] Hall of Fame. Years after his death, Roddenberry was one of the first humans to have their ashes carried into earth orbit. ''Star Trek'' has inspired films, books, comic books, video games and [[Star Trek fan productions|fan films]] set in the ''Star Trek'' universe. |

|||

Eventually, Roddenberry's dissatisfaction with his work as a freelance writer led him to produce his own television program. He came up with many story ideas and other concepts for his new television series that ultimately went unused, among them were ''Night Stick'', ''Defiance County'' and ''The Long Hunt of April Savage''; meanwhile, his first attempt, ''[[APO 923]]'', was not picked up by the networks, but in 1963, he created and produced ''[[The Lieutenant]]'', which lasted for a single season and was set inside the [[United States Marine Corps]] with [[Nichelle Nichols]] starring in the first episode. |

|||

==Early life and career== |

|||

===''Star Trek''=== |

|||

{{main|Early life and career of Gene Roddenberry}} |

|||

Roddenberry developed ''[[Star Trek]]'' in 1964, developing it as a combination of the science-fiction series [[Buck Rogers]] and [[Flash Gordon]]. Roddenberry sold the project as a "[[Wagon Train]] to the Stars", and it was picked up by [[Desilu Productions|Desilu Studios]]. The first [[television pilot|pilot]] went over its budget and received only minor support from [[NBC]]. Nevertheless, the network commissioned an unprecedented second pilot and the series premiered on September 8, 1966, and ran for three seasons. The show began to receive low [[Nielsen ratings|ratings]], and in the final season, Roddenberry left active involvement with the show (though retained his executive producer title in name only) when the network reneged on its promise for a more desirable time slot. In 1970, Paramount agreed to sell him all rights to ''Star Trek'', but Roddenberry could not afford the $150,000 (${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|150000|1970|r=-3}}}} today) price.<ref name="davies2007">{{cite book | title=NBC: America's Network | chapter=The Little Program That Could: The Relationship Between NBC and ''Star Trek'' | publisher=University of California Press | author=Davies, Máire Messenger; Pearson, Roberta | editor=Hilmes, Michele; Henry, Michael Lowell | year=2007 | url=http://books.google.com/books?id=lhmw637JRgUC&pg=PA209#v=onepage&q&f=false | isbn=0-520-25079-6}}</ref>{{rp|220}} |

|||

[[File:Gene Roddenberry 1939.JPG|thumb|left|upright|Roddenberry during his senior year of high school (1939)]] |

|||

Gene Roddenberry was born on August 19, 1921, in his parents' rented home in El Paso, Texas, the first child of Eugene Edward Roddenberry and Caroline "Glen" ({{nee|Golemon}}) Roddenberry.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 10</ref> The family moved to Los Angeles in 1923 after Gene's father passed the civil service test and was given a police commission there.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 15–17</ref> During his childhood, Roddenberry was interested in reading, especially [[pulp magazine]]s,<ref name=alexander34>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 34</ref> and was a fan of stories such as ''[[John Carter of Mars]]'', ''[[Tarzan]]'', and the ''[[Skylark (series)|Skylark]]'' series by [[E. E. Smith]].<ref name=alexander37>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 37</ref> |

|||

Roddenberry majored in [[police science]] at [[Los Angeles City College]],<ref name=alexander48>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 48</ref>{{refn|Studio biographies have erroneously credited Roddenberry as taking pre-law at Los Angeles City College, before switching to a major in engineering at the UCLA.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 47</ref>|group="n"}} where he began dating Eileen-Anita Rexroat and became interested in [[aeronautical engineering]].<ref name=alexander48/> He obtained a [[pilot licensing and certification|pilot's license]] through the [[United States Army Air Corps]]-sponsored [[Civilian Pilot Training Program]].<ref name=alexander49>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 49</ref> He enlisted with the USAAC on December 18, 1941<ref>{{cite web|title=World War II Army Enlistment Records Transcription|url=http://search.findmypast.com/record?id=usm%2fwwarmyenlist%2f2020307|publisher=[[Findmypast]]|access-date=April 28, 2015|url-access=subscription }}</ref> and married Eileen on June 13, 1942.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 54–55</ref> He graduated from the USAAC on August 5, 1942, when he was commissioned as a [[second lieutenant]].<ref name=alex59>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 59–61</ref> |

|||

The series went on to gain popularity through [[Television syndication|syndication]].<ref>Sackett, Susan (2002). Inside Trek: My Secret Life with Star Trek Creator Gene Roddenberry. Hawk Publishing Group. ISBN 1-930709-42-0.</ref> |

|||

He was posted to [[Bellows Field]], Oahu, to join the [[394th Bomb Squadron]], [[5th Bombardment Group]], of the [[Thirteenth Air Force]], which flew the [[Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress]].<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 62–63</ref> |

|||

[[File:Space shuttle enterprise star trek-cropcast.jpg|upright=1.5|thumb|Gene Roddenberry (third from the right) in 1976 with most of the cast of ''Star Trek'' at the rollout of the [[Space Shuttle]] [[Space Shuttle Enterprise|''Enterprise'']] at the [[Rockwell International]] plant at [[Palmdale, California]], USA]] |

|||

Beginning in 1975, the go-ahead was given by Paramount for Roddenberry to develop a new ''Star Trek'' television series, with many of the original cast to be included. It was originally called ''[[Star Trek: Phase II|Phase II]]''. This series was the anchor show of a new network (the ancestor of [[UPN]], which later became part of [[The CW Television Network]]), but plans by Paramount for this network were scrapped and the project was reworked into a feature film. The result, ''[[Star Trek: The Motion Picture]]'', received a lukewarm critical response, but was a hit at the box office – adjusted for [[inflation]] it was the second-highest-grossing of all ''Star Trek'' movies, with ''[[Star Trek (film)| Star Trek (2009)]]'' coming in first.<ref>{{cite web| title = Star Trek Movies at the Box Office| work = Box Office Mojo| url =http://www.boxofficemojo.com/franchises/chart/?id=startrek.htm| accessdate = February 2013}}</ref> |

|||

On August 2, 1943, while flying B-17E-BO, ''41-2463'', "Yankee Doodle", out of [[Espiritu Santo]], the plane Roddenberry was piloting overran the runway by {{convert|500|ft|m}} and crashed into trees, crushing the nose and starting a fire as well as killing two men: bombardier Sgt. John P. Kruger and navigator Lt. Talbert H. Woolam.<ref name=alexander82>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 81–82</ref> The official report absolved Roddenberry of any responsibility.<ref name=alexander82/> Roddenberry spent the remainder of his military career in the United States<ref name=alexander83>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 83</ref> and flew all over the country as a plane crash investigator. He was involved in a second plane crash, this time as a passenger.<ref name=alexander83/> He was awarded the [[Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)|Distinguished Flying Cross]] and the [[Air Medal]].<ref>[[#hamilton2007|Hamilton (2007)]]: p. 14</ref> |

|||

When asked to produce a sequel to the first movie, Roddenberry submitted a story of a time-traveling ''Enterprise'' crew involved in the [[John F. Kennedy assassination]].{{citation needed|date=November 2011}} It was rejected. He was removed as [[executive producer]] and replaced by [[Harve Bennett]].<ref name=sackett>{{cite book|author=Susan Sackett|title=Inside Trek: My Secret Life With Star Trek Creator Gene Roddenberry|publisher=HAWK Publishing Group|isbn=1-930709-42-0|year=2002}}</ref> He continued, however, as executive consultant for the next five films: ''[[Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan]]''; ''[[Star Trek III: The Search for Spock]]''; ''[[Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home]]''; ''[[Star Trek V: The Final Frontier]]''; and ''[[Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country]]''. Star Trek VI was the last film with the cast of the original ''Star Trek'' series and was dedicated to Roddenberry. He reportedly viewed an early version of the film a few days before his death.<ref name=sackett /> |

|||

In 1945, Roddenberry began flying for [[Pan American World Airways]],<ref name=alex85/> including routes from New York to Johannesburg or Calcutta, the two longest Pan Am routes at the time.<ref name=alex85>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 85</ref> Listed as a resident of [[River Edge, New Jersey]], he experienced his third crash while on the [[Pan Am Flight 121|Clipper ''Eclipse'']] on June 18, 1947.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Freeze|first1=Christopher|title=Clipper Eclipse|url=http://www.check-six.com/Crash_Sites/ClipperEclipse-NC88845.htm|website=Check-Six.com|access-date=September 6, 2016|url-status=live|archive-date=24 September 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160924104855/http://www.check-six.com/Crash_Sites/ClipperEclipse-NC88845.htm}}</ref> The plane came down in the [[Syrian Desert]], and Roddenberry, who took control as the ranking flight officer, suffered two [[Rib fracture|broken ribs]] but was able to drag injured passengers out of the burning plane and led the group to get help.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 91–95</ref> Fourteen (or fifteen)<ref>[https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=gL9scSG3K_gC&dat=19470620&printsec=frontpage&hl=en "Clipper Plane Crash Kills 14"], ''Pittsburgh Post-Gazette'', June 20, 1947, p4</ref> people died in the crash; eleven passengers required hospital treatment (including [[Bishnu Charan Ghosh]]), and eight were unharmed.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 97–98</ref> Roddenberry resigned from Pan Am on May 15, 1948, and decided to pursue his dream of writing, particularly for the new medium of television.<ref name=alex103>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 103–104</ref> |

|||

Roddenberry was deeply involved with creating and producing ''[[Star Trek: The Next Generation]]''. His participation greatly decreased after the first installment, although this was not publicly disclosed because of the value of his name to fans. Besides ''The Next Generation'', Roddenberry was credited with "Based on Star Trek by Gene Roddenberry" on ''[[Star Trek: Deep Space Nine]]'', ''[[Star Trek: Voyager]]'', and ''[[Star Trek: Enterprise]]''.{{r|pearson2011}}{{rp|114}} |

|||

Roddenberry applied for a position with the [[Los Angeles Police Department]] on January 10, 1949,<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 110</ref> and spent his first sixteen months in the traffic division before being transferred to the newspaper unit.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 114</ref> That became the Public Information Division, and Roddenberry became the Chief of Police's speech writer.<ref name="Alexander 1995 p. 115">[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 115</ref> In this position, he also became the LAPD liaison to the very popular ''[[Dragnet (franchise)|Dragnet]]'' television series, providing technical advisors for specific episodes. He also did his first TV writing for the show, taking actual cases, and boiling them down to short screen treatments that would be fleshed out into full scripts by [[Jack Webb|Jack Webb's]] staff of writers, and splitting the fee with the officers who actually investigated the real-life case. He became then technical advisor for a new television version of ''[[Mr. District Attorney]]'', which led to him writing for the show under his pseudonym "Robert Wesley".<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 135–137</ref> He began to collaborate with [[Ziv Television Programs]]<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]] p. 145</ref> and continued to sell scripts to ''Mr. District Attorney'', in addition to Ziv's ''[[Highway Patrol (U.S. TV series)|Highway Patrol]]''. In early 1956, he sold two story ideas for ''[[I Led Three Lives]]'', and he found that it was becoming increasingly difficult to be a writer and a policeman.<ref name=alex148>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 148</ref> On June 7, 1956, he resigned from the force to concentrate on his writing career.<ref name=alex151>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 151</ref> |

|||

In addition to his film and TV work, Roddenberry also wrote the novelization of ''[[Star Trek: The Motion Picture]]''. It was published in 1979 and was the first of hundreds of ''Star Trek''-based novels to be published by the [[Pocket Books]] unit of [[Simon & Schuster]], whose parent company also owned [[Paramount Pictures Corporation]]. Because [[Alan Dean Foster]] wrote the original treatment of the ''[[Star Trek: The Motion Picture]]'' film, there was{{Who|date=October 2009}} a rumor that Foster was the [[ghostwriter]] of the novel. This has been debunked by Foster on his personal web site. (Foster did, however, ghostwrite the novelization of [[George Lucas]]'s ''[[Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope|Star Wars]]''.) Roddenberry talked of writing a second ''Trek'' novel based on his rejected 1975 script of the [[John F. Kennedy assassination|JFK assassination]] plot, but he died before he was able to do so.<ref>Starlog #16, September, 1978, "Star Trek Report" by Susan Sackett as quoted by "The God Thing: Gene Roddenberry's Lost Star Trek Novel" at http://www.well.com/~sjroby/godthing.html</ref> |

|||

==Career as full-time writer and producer== |

|||

Roddenberry is reported to have made comments regarding what was to be considered [[canon (fiction)|canonical]] material in the fictional Star Trek universe, even toward the end of his life. In particular, claims have been made about his expressed opinions as to the place of the films ''[[Star Trek V: The Final Frontier]]'', ''[[Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country]]'', and ''[[Star Trek: The Animated Series]]'' in [[Star Trek canon]]. |

|||

{{see also|Gene Roddenberry filmography}} |

|||

===Early career=== |

|||

''Star Trek'' is a rare instance of a television series gaining substantially in popularity and cultural currency long after cancellation (see main article, [[Cultural influence of Star Trek]]). Perhaps inevitably, then, there has been some contention over the years regarding proper attribution of artistic credit and assignment of royalties related to the show. A few writers and other production staff for the series have said that ideas they developed were later claimed by Roddenberry as his own, or that Roddenberry discounted their contributions and involvement. Roddenberry was confronted by some of these people, and he apologized to them; but according to at least one critic, he continued to claim undue credit.<ref name="engel">{{cite book |last=Engel |first=Joel |year=1994 |title=Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek |publisher=Hyperion Books |isbn=0-7868-6004-9}} Inside Star Trek: The Real Story (1996) commentary by Star Trek producer [[Herb Solow|Herbert F. Solow]], science-fiction convention talks by Star Trek writer Dorothy C. Fontana, and books and articles by [[Harlan Ellison]].</ref> |

|||

Roddenberry was promoted to head writer for ''[[The West Point Story (TV series)|The West Point Story]]'' and wrote ten scripts for the first season, about a third of the total episodes.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 160</ref> While working for Ziv, in 1956, he pitched a series to [[CBS]] set aboard a [[cruise ship]], ''Hawaii Passage'',<ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Gross |editor1-first=Edward |editor2-last=Altman |editor2-first=Mark A. |editor2-link=Mark A. Altman |title=The Fifty-Year Mission: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Star Trek: The First 25 Years |date=June 2016 |publisher=[[Thomas Dunne Books]] |location=New York, NY |isbn=978-1-250-06584-1 |page=66 |edition=1st |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CCN3CgAAQBAJ&q=%22gene+roddenberry%22+%22hawaii+passage%22&pg=PA66 |access-date=May 12, 2019 |chapter=Gene had been a big fan of 1961's Master of the World. But less known is that five years earlier, in 1956, Gene had pitched an idea for a new series called Hawaii Passage, which followed the adventures of a cruise ship, her captain, and senior officers. What was different here was that Gene referred to the ship as one of the characters, unheard of at the time.}}</ref> but they did not buy it, as he wanted to become a [[Producer (television)|producer]] and have full creative control. He wrote another script for Ziv's series ''[[Harbourmaster (TV series)|Harbourmaster]]'' titled "Coastal Security" and signed a contract with the company to develop a show called ''Junior Executive'' with [[Quinn Martin]]. Nothing came of the series.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 162–164</ref> |

|||

[[File:Leonard Nimoy mid 1960s.JPG|thumb|right|upright|[[Leonard Nimoy]] first worked with Roddenberry on ''The Lieutenant''.]] |

|||

He wrote scripts for a number of other series in his early years as a professional writer, including ''[[Fireside Theatre|The Jane Wyman Show]]'', ''[[Bat Masterson (TV series)|Bat Masterson]]'' and ''[[Jefferson Drum]]''.<ref name=alex167/> Roddenberry's episode of the series ''[[Have Gun – Will Travel]]'', "Helen of Abajinian", won the [[Writers Guild of America]] award for Best Teleplay in 1958.<ref name="reginald1052"/> He also continued to create series of his own, including a series based on an agent for [[Lloyd's of London]] called ''The Man from Lloyds''. He pitched a police-based series called ''Footbeat'' to CBS, Hollis Productions, and [[Screen Gems]]. It nearly made it into [[ABC (TV station)|ABC]]'s Sunday-night lineup, but they opted to show only [[Western (genre)|Western]] series that night.<ref name=alex167>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 166–167</ref> |

|||

Roddenberry was asked to write a series called ''Riverboat'', set in 1860s Mississippi. When he discovered that the producers wanted no black people on the show, he argued so much with them that he lost the job.<ref>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 13</ref> He also considered moving to England around this time, as <!-- Not knighted until 1969. -->[[Lew Grade]]<!-- Much more likely the affiliated ITC (aimed at the US market) rather than the previously listed Associated Television (UK domestic ITV contractor), but no confirmation & source not online. --> wanted Roddenberry to develop series and set up his own production company.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 170</ref> Though he did not move, he leveraged the deal to land a contract with Screen Gems that included a guaranteed $100,000, and became a producer for the first time on a summer replacement for ''[[The Ford Show|The Tennessee Ernie Ford Show]]'' titled ''[[Wrangler (TV series)|Wrangler]]''.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 175</ref> |

|||

''Star Trek'' theme music composer [[Alexander Courage]] long harbored resentment of Roddenberry's attachment of lyrics to his composition. By union rules, this resulted in the two men splitting the music royalties payable whenever an episode of ''Star Trek'' aired, which otherwise would have gone to Courage in full.<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.snopes.com/radiotv/tv/trek1.htm |title = Unthemely Behavior |accessdate = May 20, 2007 |date = August 8, 2007|work = [[Urban Legends Reference Pages]]}}</ref> (The lyrics were never used on the show, but were performed by [[Nichelle Nichols]] on her 1991 album, "Out of this World.") Later, while cooperating with Stephen Whitfield for the latter's book ''The Making of Star Trek,'' Roddenberry demanded and received Whitfield's acquiescence for 50 percent of that book's royalties. As Roddenberry explained to Whitfield in 1968: <blockquote>I had to get some money somewhere. I'm sure not going to get it from the profits of ''Star Trek''.<ref>[[Herb Solow|Herbert F. Solow]] & [[Robert H. Justman]], Inside Star Trek: the Real Story, Pocket Books, 1996, p. 402.</ref></blockquote> Herbert Solow and [[Robert H. Justman]] observe that Whitfield never regretted his fifty-fifty deal with Roddenberry since it gave him "the opportunity to become the first chronicler of television's successful unsuccessful series".<ref>Solow & Justman, p. 402.</ref> |

|||

Screen Gems backed Roddenberry's first attempt at creating a pilot. His series, ''The Wild Blue'', went to pilot, but was not picked up. The three main characters had names that later appeared in the ''Star Trek'' series: Philip Pike, Edward Jellicoe, and James T. Irvine.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 179–180</ref> While working at Screen Gems, an actress, new to Hollywood, wrote to him asking for a meeting. They quickly became friends and met every few months; the woman was [[Majel Barrett|Majel Leigh Hudec]], later known as Majel Barrett.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 181</ref> He created a second pilot called ''333 Montgomery'' about a lawyer, played by [[DeForest Kelley]].<ref name=hise15>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 15</ref> It was not picked up by the network but was later rewritten as a new series called ''Defiance County''. His career with Screen Gems ended in late 1961,<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 182</ref> and shortly afterward, he had issues with his old friend [[Erle Stanley Gardner]]. The ''[[Perry Mason]]'' creator claimed that ''Defiance County'' had infringed his character [[Doug Selby]].<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 186</ref> The two writers fell out via correspondence and stopped contacting one another, though ''Defiance County'' never proceeded past the pilot stage.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 195</ref> The project finally wound up as the NBC series ''[[Sam Benedict]]'' with [[Edmond O'Brien]] in the title role, produced by MGM. E. Jack Neuman took the creator's credit; claiming the character was based on real-life San Francisco lawyer [[Jake Ehrlich]].<ref>https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0507862/ {{User-generated source|certain=yes|date=August 2022}}</ref><ref>https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0055703/trivia/?ref_=tt_trv_trv {{User-generated source|certain=yes|date=August 2022}}</ref> |

|||

===Other television work=== |

|||

[[File:MONY Gene Roddenberry.JPG|thumb|left|Roddenberry appearing in an advertisement for MONY in 1961]] |

|||

Aside from ''Star Trek'', Roddenberry produced ''[[Pretty Maids All in a Row]]'', a [[sexploitation]] film adapted from the novel written by Francis Pollini and directed by [[Roger Vadim]]. The cast included [[Rock Hudson]], [[Angie Dickinson]], [[Telly Savalas]] and [[Roddy McDowall]] alongside ''Star Trek'' regular [[James Doohan]] and [[William Campbell (film actor)|William Campbell]] (who appeared as a guest in two ''Star Trek'' episodes). It also featured Gretchen Burrell, the wife of country-rock pioneer [[Gram Parsons]]. Despite Roddenberry's expectations, the film was not a success. |

|||

In 1961, he agreed to appear in an advertisement for [[MONY]] (Mutual of New York) as long as he had final approval.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 198</ref> With the money from Screen Gems and other works, he and Eileen moved to 539 South Beverly Glen, near [[Beverly Hills]].<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 200</ref> He discussed an idea about a multi-ethnic crew on an [[airship]] traveling the world, based on the film ''[[Master of the World (1961 film)|Master of the World]]'' (1961), with fellow writer [[Christopher Knopf]] at [[MGM]]. As the time was not right for science fiction, he began work on ''[[The Lieutenant]]'' for Arena Productions. This made it to the [[NBC]] Saturday night lineup at 7:30 pm<ref name=alex201/> and premiered on September 14, 1963. The show set a new ratings record for the time slot.<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=25}}</ref> Roddenberry worked with several cast and crew who would later join him on ''Star Trek'', including [[Gene L. Coon]], star [[Gary Lockwood]], Joe D'Agosta, [[Leonard Nimoy]], [[Nichelle Nichols]], and Majel Barrett.<ref name=alex201>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 201–202</ref> |

|||

''The Lieutenant'' was produced with the co-operation of [[the Pentagon]], which allowed them to film at an actual Marine base. During the production of the series Roddenberry clashed regularly with the [[United States Department of Defense|Department of Defense]] over potential plots.<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=26}}</ref> The department withdrew its support after Roddenberry pressed ahead with a plot titled "[[To Set It Right]]" in which a white and a black man find a common cause in their roles as Marines.<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=28}}</ref><ref name=nichols122/> "To Set It Right" was the first time he worked with Nichols, and it was her first television role. The episode has been preserved at the [[Museum of Television and Radio]] in New York City.<ref name=nichols122>[[#nichols1994|Nichols (1994)]]: p. 122</ref> The show was not renewed after its first season. Roddenberry was already working on a new series idea. This included his ship location from ''Hawaii Passage'' and added a [[Horatio Hornblower]] character, plus the multiracial crew from his airship idea. He decided to write it as science fiction, and by March 11, 1964, he brought together a 16-page pitch. On April 24, he sent three copies and two dollars to the [[Writers Guild of America]] to register his series. He called it ''Star Trek''.<ref name=alex204>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 204</ref> |

|||

In the early 1970s, Roddenberry pitched pilots for three sci-fi TV series concepts, although none were developed as series: ''[[The Questor Tapes]]''; ''[[Spectre (film)|Spectre]]'', and ''[[Genesis II (film)|Genesis II]]''. ABC asked to see another TV movie using the characters from ''Genesis II'', but with more action, and Roddenberry produced ''[[Planet Earth (TV pilot)|Planet Earth]]''. He was not, however, involved in a third TV Movie, ''[[Strange New World (television pilot)|Strange New World]]'', which used some of the characters and situations from ''Planet Earth'', but with a different original story. |

|||

===''Star Trek''=== |

|||

Roddenberry feared that he would be unable to provide for his family, as he was unable to find work in the television and film industry and was facing possible bankruptcy.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

|||

{{main|Star Trek: The Original Series}} |

|||

When Roddenberry pitched ''Star Trek'' to MGM, it was warmly received, but no offer was made.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 206</ref> He then went to [[Desilu Productions]], but rather than being offered a one-script deal, he was hired as a producer and allowed to work on his own projects. His first was a half-hour pilot called ''Police Story'' (not to be confused with [[Police Story (1973 TV series)|the anthology series]] created by [[Joseph Wambaugh]]), which was not picked up by the networks.<ref name=alex211/> Having not sold a pilot in five years, Desilu was having financial difficulties; its only success was ''[[The Lucy Show]]''.<ref name=vanhise20>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 20</ref> Roddenberry took the ''Star Trek'' idea to Oscar Katz, head of programming, and the duo immediately started work on a plan to sell the series to the networks. They took it to CBS, which ultimately passed on it. The duo later learned that CBS had been eager to find out about ''Star Trek'' because it had a science fiction series in development—''[[Lost in Space]]''. Roddenberry and Katz next took the idea to Mort Werner at NBC,<ref name=vanhise20/> this time downplaying the science fiction elements and highlighting the links to ''[[Gunsmoke]]'' and ''[[Wagon Train]].''<ref name=alex211>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 211–212</ref> The network funded three story ideas and selected "The Menagerie", which was later known as "[[The Cage (Star Trek: The Original Series)|The Cage]]", to be made into a pilot. (The other two later became episodes of the series.) While most of the money for the pilot came from NBC, the remaining costs were covered by Desilu.<ref name=alex213>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 213</ref><ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 216</ref> Roddenberry hired Dorothy Fontana, better known as [[D. C. Fontana]], as his assistant. They had worked together previously on ''The Lieutenant,'' and she had eight script credits to her name.<ref name=vanhise20/> |

|||

[[File:William Shatner Sally Kellerman Star Trek 1966.JPG|thumb|right|upright|[[William Shatner]] and [[Sally Kellerman]], from "[[Where No Man Has Gone Before]]", the second pilot of ''Star Trek'']] |

|||

==Marriages== |

|||

Roddenberry and Barrett had begun an affair by the early days of ''Star Trek'',<ref name=alex213/> and he specifically wrote the part of the character [[Number One (Star Trek)|Number One]] in the pilot with her in mind; no other actresses were considered for the role. Barrett suggested [[Leonard Nimoy|Nimoy]] for the part of [[Spock (Star Trek)|Spock]]. He had worked with both Roddenberry and Barrett on ''The Lieutenant'', and once Roddenberry remembered the thin features of the actor, he did not consider anyone else for the part.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 227–228</ref> The remaining cast came together; filming began on November 27, 1964, and was completed on December 11.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 234–236</ref> After post-production, the episode was shown to NBC executives, and it was rumored that ''Star Trek'' would be broadcast at 8:00 pm on Friday nights. The episode failed to impress test audiences,<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 238</ref> and after the executives became hesitant, Katz offered to make a second pilot. On March 26, 1965, NBC ordered a new episode.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 243–244</ref> |

|||

In 1942, Roddenberry married Eileen Rexroat. They had two daughters, Darleen and Dawn, but during the 1960s, he had affairs with [[Nichelle Nichols]] (said by Nichols to be the reason he wanted her on the show)<ref>Nichelle Nichols, Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, G.P. Putnam & Sons, New York, 1994.</ref> and [[Majel Barrett]]. Twenty-seven years after his first marriage, Roddenberry divorced his first wife and married Barrett in Japan in a traditional [[Shinto]] ceremony on August 6, 1969, and they had one child together, [[Rod Roddenberry|Eugene Wesley Roddenberry, Jr.]]<ref>{{cite book|title=Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry|author=David Alexander|publisher=Roc|year=1994|isbn=0-451-45440-5}}</ref> |

|||

Roddenberry developed several possible scripts, including "[[Mudd's Women]]", "[[The Omega Glory]]", and with the help of [[Samuel A. Peeples]], "[[Where No Man Has Gone Before]]". NBC selected the last one, leading to later rumors that Peeples created ''Star Trek'', something he always denied.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 246–248</ref> Roddenberry was determined to make the crew racially diverse, which impressed actor [[George Takei]] when he came for his audition.<ref>{{harvp|Takei|1994|p=149}}</ref> The episode went into production on July 15, 1965, and was completed at around half the cost of "The Cage", since the sets were already built.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 252</ref> Roddenberry worked on several projects for the rest of the year. In December, he decided to write lyrics to the ''Star Trek'' theme; this angered the theme's composer, [[Alexander Courage]], as it meant that royalties would be split between them. In February 1966, NBC informed Desilu that they were buying ''Star Trek'' and that it would be included in the fall 1966 television schedule.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 255–256</ref> |

|||

==Religious views== |

|||

Although Roddenberry was raised as a [[Southern Baptist]], he instead considered himself a [[humanism|humanist]] and [[agnosticism|agnostic]]. He saw religion as the cause of many wars and human suffering.<ref>{{cite journal |author= |year=1991 |month=March/April |title=Roddenberry Interview |journal=The Humanist |volume=51 |issue=2}}</ref> [[Brannon Braga]] has said that Roddenberry made it known to the writers of ''Star Trek'' and ''Star Trek: The Next Generation'' that religion and mystical thinking were not to be included, and that in Roddenberry's vision of Earth's future, everyone was an atheist and better for it.<ref>{{cite conference | last = Braga | first = Brannon |

|||

| title = Every religion has a mythology |

|||

| booktitle = International Atheist Conference |

|||

| place = Reykjavik, Iceland |

|||

| date = June 24, 2006 |

|||

| url = http://sidmennt.is/2006/08/16/every-religion-has-a-mythology/ |

|||

| accessdate = May 11, 2009 }}</ref> However, Roddenberry was clearly not punctilious in this regard, and some religious references exist in various episodes of both series under his watch. The original series episodes "[[Bread and Circuses (Star Trek: The Original Series)|Bread and Circuses]]", "[[Who Mourns for Adonais?]]" and "[[The Ultimate Computer]]", and the ''Star Trek: The Next Generation'' episodes "[[Data's Day]]" and "[[Where Silence Has Lease]]" are examples. On the other hand, "[[Metamorphosis (Star Trek: The Original Series)|Metamorphosis]]", "[[The Empath]]", "[[Who Watches the Watchers]]", and several others reflect his agnostic views. |

|||

He stubbornly resisted the effort of network execs to put a Christian chaplain on the crew of the Enterprise. It would be ludicrous, he argued, to pretend that all other religions would have become obliterated by this point, or that such a cosmopolitan people would impose one group's religion on all the rest of the crew.<ref>{{cite conference | title = Gene Roddenberry |

|||

| year = 2012 |

|||

| url = http://www.nndb.com/people/503/000022437/ |

|||

| accessdate = October 25, 2012 }}</ref> |

|||

On May 24, the first episode of the ''Star Trek'' series went into production;<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 272</ref> Desilu was contracted to deliver 13 episodes.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 275</ref> Five days before the first broadcast, Roddenberry appeared at the 24th [[World Science Fiction Convention]] and previewed "Where No Man Has Gone Before". After the episode was shown, he received a standing ovation. The first episode to air on NBC was "[[The Man Trap]]", on September 8, 1966, at 8:00 pm.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 278</ref> Roddenberry was immediately concerned about the series' low ratings and wrote to [[Harlan Ellison]] to ask if he could use his name in letters to the network to save the show. Not wanting to lose a potential source of income, Ellison agreed and also sought the help of other writers who also wanted to avoid losing potential income.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 284</ref> Roddenberry corresponded with science fiction writer [[Isaac Asimov]] about how to address the issue of Spock's growing popularity and the possibility that his character would overshadow Kirk.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 304</ref> Asimov suggested having Kirk and Spock work together as a team "to get people to think of Kirk when they think of Spock."<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 307</ref> The series was renewed by NBC, first for a full season's order, and then for a second season. An article in the ''[[Chicago Tribune]]'' quoted studio executives as stating that the letter-writing campaign had been wasted because they had already been planning to renew ''Star Trek''.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 287</ref> |

|||

==Death and legacy== |

|||

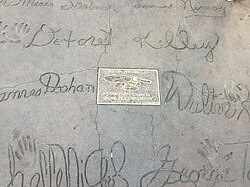

[[File:Gene Roddenberry - Star for TV.png|thumb|right|200px|Roddenberry's star at 6683 [[Hollywood Boulevard]] on [[Hollywood, Los Angeles, California|Hollywood]]'s [[Hollywood Walk of Fame|Walk of Fame]], presented in 1985. He was the first television writer to receive a star.<ref name="pearson2011">{{cite book | title=Television as Digital Media | publisher=Duke University Press | author=Pearson, Roberta | year=2011 | editor=Bennett, James; Strange, Niki | chapter = Cult Television as Digital Television's Cutting Edge | url=http://books.google.com/books?id=3cYJndq9K1IC&pg=PA105#v=onepage&q&f=false | pages=105–131 | isbn=0-8223-4910-8}}</ref>{{rp|110}}]] |

|||

Roddenberry died from [[cardiopulmonary arrest]], on October 24, 1991.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.nytimes.com/1991/10/26/movies/gene-roddenberry-star-trek-creator-dies-at-70.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm|title=Gene Roddenberry, 'Star Trek' Creator, Dies at 70|first=Robert D.|last= McFadden|date=26 October 1991|publisher=The New York Times|accessdate=17 August 2012}}</ref> The second episode of ''[[Star Trek: The Next Generation]]'' to air after his death, "[[Unification (Star Trek: The Next Generation)|Unification]]", featured a dedication to Roddenberry. In 1992, a portion of Roddenberry's ashes flew and returned to earth on the [[Space Shuttle Columbia|Space Shuttle ''Columbia'']] mission [[STS-52]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=348&dat=19940429&id=bUMvAAAAIBAJ&sjid=CjMDAAAAIBAJ&pg=1725,8689414|title=Shuttle bore Roddenberry's ashes|publisher=[[Rome News-Tribune]]|date=April 29, 1994|accessdate=August 4, 2012}}</ref> On April 21, 1997, a [[Celestis| Celestis spacecraft]] — carrying portions of the cremated remains of Roddenberry, of [[Timothy Leary]] and of 22 other individuals — was launched into Earth orbit aboard a [[Pegasus (rocket)|Pegasus XL]] rocket from near the [[Canary Islands]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.celestis.com/foundersFlight.asp|title=The Founders Flight|publisher=celestis.com}}, Retrieved 2011-11-14.</ref> On May 20, 2002, the spacecraft's orbit deteriorated and it disintegrated in the atmosphere. Another flight to launch more of his ashes into deep space along with those of Majel (Barrett) Roddenberry, his widow who died in 2008, is planned for launch in 2014.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.celestis.com/memorial/voyager/default.asp|title=Celestis Voyager Flight Participants|publisher=celestis.com}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Star Trek crew members.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Some of the main cast of ''Star Trek'' during the third season]] |

|||

After his death, Roddenberry's estate permitted the filming of ''[[Earth: Final Conflict]]'' and ''[[Andromeda (TV series)|Andromeda]]'', two television series which were based on his unused stories. A third story idea{{Citation needed|date=August 2010}} was adapted in 1995 as the [[comic book]] ''Gene Roddenberry's Lost Universe'' (later titled ''Gene Roddenberry's Xander in Lost Universe''). ''Gene Roddenberry's Starship'', was a computer-animated series that was proposed by Majel Barrett and [[John Semper]] but was not produced.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0EIN/is_1998_Oct_20/ai_53099756|date=October 20, 1998|accessdate=December 18, 2007|title=Mainframe Entertainment Lands Gene Roddenberry's 'Starship' for Computer Animated Television Series|publisher=BNet Research Center}}</ref> |

|||

Roddenberry often rewrote submitted scripts, although he did not always take credit for these.<ref name=alex314>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 314</ref> Roddenberry and Ellison fell out over "[[The City on the Edge of Forever]]" after Roddenberry rewrote Ellison's script to make it both financially feasible to film and usable for the series context.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 313</ref> Even his close friend [[Don Ingalls]] had his script for "[[A Private Little War]]" altered drastically,<ref name=alex314/> and as a result, Ingalls declared that he would only be credited under the pseudonym "Jud Crucis" (a play on "Jesus Christ"), claiming he had been crucified by the process.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 315</ref> Roddenberry's work rewriting "[[The Menagerie (Star Trek: The Original Series)|The Menagerie]]", based on footage originally shot for "The Cage", resulted in a Writers Guild arbitration board hearing. The Guild ruled in his favor over [[John D. F. Black]], the complainant.<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=118}}</ref> The script won a [[Hugo Award]], but the awards board neglected to inform Roddenberry, who found out through correspondence with Asimov.<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|pp=120–121}}</ref> |

|||

As the second season was drawing to a close, Roddenberry once again faced the threat of cancellation. He enlisted the help of Asimov,<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 327</ref> and even encouraged a student-led protest march on NBC. On January 8, 1968, a thousand students from 20 schools marched on the studio.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 329</ref> Roddenberry began to communicate with ''Star Trek'' fan [[Bjo Trimble]], who led a fan-writing campaign to save the series. Trimble later noted that this campaign of writing to fans who had written to Desilu about the show, urging them to write NBC, had created an organized [[Star Trek fandom|''Star Trek'' fandom]].<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 336–337</ref> The network received around 6,000 letters a week from fans petitioning it to renew the series.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 338</ref> On March 1, 1968, NBC announced on air, at the end of "The Omega Glory", that ''Star Trek'' would return for a third season.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 341</ref> |

|||

Roddenberry and his wife Majel were honored by the [[Space Foundation]] in 2002 with the Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award,<ref>[http://2010.nationalspacesymposium.org/about-the-show/symposium-awards/douglas-s-morrow-public-outreach-award Foundation Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award]</ref> in recognition of their contributions to awareness of and enthusiasm for space exploration. |

|||

The network had initially planned to place ''Star Trek'' in the 7:30 pm Monday-night time slot freed up by ''[[The Man from U.N.C.L.E.]]'' completing its run. That would have meant ''[[Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In]]'' had to start a half-hour later (moving from 9:00 to 9:30). Powerful ''Laugh-In'' producer [[George Schlatter]] objected to his highly rated show yielding its slot to the poorly-rated ''Star Trek''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tvobscurities.com/articles/star_trek_look/|title=A Look At Star Trek – Television Obscurities|work=Television Obscurities|date=May 24, 2009 |access-date=May 16, 2022|quote=Citing: “‘Laugh-In’ staying put.” ''Broadcasting''. 18 Mar. 1968: 9.}}</ref> Instead, ''Laugh-In'' retained the slot, and ''Star Trek'' was moved to 10:00 pm on Fridays. Realizing the show could not survive in that time slot and burned out from arguments with the network, Roddenberry resigned from the day-to-day running of ''Star Trek'', although he continued to be credited as executive producer.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 342–343</ref> Roddenberry cooperated with Stephen Edward Poe, writing as Stephen Whitfield, on the 1968 non-fiction book ''The Making of Star Trek'' for Ballantine Books, splitting the royalties evenly. Roddenberry explained to Whitfield: "I had to get some money somewhere. I'm sure not going to get it from the profits of ''Star Trek''."<ref name=sojust402>[[#solowjustman1996|Solow & Justman (1996)]]: p. 402</ref> Herbert Solow and [[Robert H. Justman]] observed that Whitfield never regretted his 50–50 deal with Roddenberry, since it gave him "the opportunity to become the first chronicler of television's successful unsuccessful series."<ref name=sojust402/> Whitfield had previously been the national advertising and promotion director for model makers [[Aluminum Model Toys]], better known as "AMT", which then held the ''Star Trek'' license, and moved to run [[Lincoln Enterprises]], Roddenberry's company set up to sell the series' merchandise.<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=123}}</ref> |

|||

Roddenberry was inducted into the [[Television Academy Hall of Fame]] in 2010. |

|||

Having stepped aside from the majority of his ''Star Trek'' duties, Roddenberry sought instead to create a film based on Asimov's "[[I, Robot]]" and also began work on a ''Tarzan'' script for [[National General Pictures]].<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 390–391</ref> After initially requesting a budget of $2 million and being refused, Roddenberry made cuts to reduce costs to $1.2 million. When he learned they were being offered only $700,000 to shoot the film, which by now was being called a TV movie, he canceled the deal.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: pp. 393–394</ref> NBC announced ''Star Trek''{{'s}} cancellation in February 1969. A similar but much smaller letter-writing campaign followed news of the cancellation.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 398</ref> Because of the manner in which the series was sold to NBC, it left the production company $4.7 million in debt.<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 399</ref> The last episode of ''Star Trek'' aired 47 days before [[Neil Armstrong]] stepped onto the moon as part of the [[Apollo 11]] mission,<ref>[[#alexander1995|Alexander (1995)]]: p. 400</ref> and Roddenberry declared that he would never write for television again.<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=175}}</ref> |

|||

== Filmography == |

|||

===1970s projects=== |

|||

"Atop the Fourth Wall" (1 episode) |

|||

[[File:Rock Hudson, Gene Roddenberry, Roger Vadim, and cast of Pretty Maids All in a Row.jpg|thumb|left|Cast of ''[[Pretty Maids All in a Row]]'' (L-R): (front row) [[June Fairchild]], [[Joy Bang]], Aimee Eccles; (middle row) [[Joanna Cameron]], Gene Roddenberry, [[Rock Hudson]], [[Roger Vadim]]; (back row) [[Margaret Markov]], [[Brenda Sykes]], Diane Sherry, Gretchen Burrell]] |

|||

... aka "At4W" - USA (short title) |

|||

After the cancellation of ''Star Trek,'' Roddenberry felt [[Typecasting (acting)|typecast]] as a producer of science fiction, despite his background in Westerns and police stories.<ref>[[#asherman1988|Asherman (1988)]]: p. 13</ref> He later described the period, saying, "My dreams were going downhill because I could not get work after the original series was cancelled."<ref>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 45</ref> He felt that he was "perceived as the guy who made the show that was an expensive flop."<ref>{{cite news|last1=Schonauer|first1=David|title=What's important is what hasn't changed|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1876&dat=19880422&id=qzwsAAAAIBAJ&pg=6960,2530069&hl=en|access-date=April 15, 2015|work=Herald-Journal|issue=113|date=April 22, 1988|volume=58|page=B8|via=[[Google News]]}}</ref> Roddenberry had sold his interest in ''Star Trek'' to [[Paramount Studios]] in return for a third of the profits but this did not result in any quick financial gain; the studio was still claiming that the series was $500,000 in the red in 1982.<ref>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 58</ref> |

|||

He wrote and produced ''[[Pretty Maids All in a Row]]'' (1971), a [[sexploitation]] film directed by [[Roger Vadim]], for MGM. The cast included [[Rock Hudson]], [[Angie Dickinson]], [[Telly Savalas]], and [[Roddy McDowall]] alongside ''Star Trek'' regular [[James Doohan]] and notable guest star [[William Campbell (film actor)|William Campbell]], who had appeared in "[[The Squire Of Gothos]]" and "[[The Trouble with Tribbles]]". ''[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]]'' was unimpressed: "Whatever substance was in the original [novel by Francis Pollini] or screen concept has been plowed under, leaving only superficial, one-joke results."<ref>{{cite news|title=Review: 'Pretty Maids All in a Row'|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150112054028/http://variety.com/1970/film/reviews/pretty-maids-all-in-a-row-1200422446/|archive-date=January 12, 2015|url=https://variety.com/1970/film/reviews/pretty-maids-all-in-a-row-1200422446/|access-date=March 25, 2015|work=Variety|date=December 31, 1970}}</ref> Herbert Solow had given Roddenberry the work as a favor, paying him $100,000 for the script.<ref name="engel139"/> |

|||

#Youngblood #4/Star Trek III: The Search for Spock #1 (13 February 2012) - special thanks |

|||

[[File:Gene roddenberry 1976.jpg|thumb|upright|right|Roddenberry at a ''Star Trek'' convention in 1976]] |

|||

"Star Trek: GENESIS" (2 episodes ) |

|||

Faced with a mortgage and a $2,000-per-month alimony obligation as a result of his 1969 divorce, he retained a booking agent (with the assistance of his friend [[Arthur C. Clarke]]) and began to support himself largely by scheduling appearances at colleges and science fiction conventions.<ref name=engel140>[[#engel1994|Engel (1994)]]: p. 140</ref><ref>[[#nemecek2003|Nemecek (2003)]]: p. 2</ref> These presentations typically included screenings of "The Cage" and blooper reels from the production of ''Star Trek.''<ref>{{cite news|title='Star Trek' creator brings banned pilot to the Arena Sunday|url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/2295345//|access-date=April 26, 2015|work=San Antonio Express|date=January 7, 1977|page=4C|url-access=subscription |via=[[Newspapers.com]]}} {{open access}}</ref> The conventions began to build the fan support to bring back ''Star Trek,'' leading ''[[TV Guide]]'' to describe it, in 1972, as "the show that won't die."<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=149}}</ref> |

|||

In 1972 and 1973, Roddenberry made a comeback to science fiction, selling ideas for four new series to a variety of networks.<ref name=hise59/> Roddenberry's ''[[Genesis II (film)|Genesis II]]'' was set in a post-apocalyptic Earth. He had hoped to recreate the success of ''Star Trek'' without "doing another space-hopping show." He created a 45-page writing guide, and proposed several story ideas based on the concept that pockets of civilisation had regressed to past eras or changed altogether.<ref>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 60</ref> The pilot aired as a TV movie in March 1973, setting new records for the ''Thursday Night Movie of the Week''. Roddenberry was asked to produce four more scripts for episodes, but before production could begin again, CBS aired the film ''[[Planet of the Apes (1968 film)|Planet of the Apes]].'' It was watched by an even greater audience than ''Genesis II.'' CBS scrapped ''Genesis II'' and replaced it with a [[Planet of the Apes (TV series)|television series]] based on the film; the results were disastrous from a ratings standpoint, and ''Planet of the Apes'' was canceled after 14 episodes.<ref>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 61</ref> |

|||

#Slave World (1 January 2012) - Writer (creator) |

|||

#Alone (6 October 2012) - Writer (creator) |

|||

''[[The Questor Tapes]]'' project reunited him with his ''Star Trek'' collaborator, Gene L. Coon, who was in poor health. NBC ordered 16 episodes, and tentatively scheduled the series to follow ''[[The Rockford Files]]'' on Friday nights;<ref name=hise65/> the pilot launched on January 23, 1974,<ref>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 63</ref> to positive critical response, but Roddenberry balked at the substantial changes requested by the network and left the project, leading to its immediate cancellation. During 1974, Roddenberry reworked the ''Genesis II'' concept as a second pilot, ''[[Planet Earth (film)|Planet Earth]],'' for rival network ABC, with similar less-than-successful results. The pilot was aired on April 23, 1974. While Roddenberry wanted to create something that could feasibly exist in the future, the network wanted stereotypical science-fiction women and were unhappy when that was not delivered.<ref name=hise65>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 65</ref> Roddenberry was not involved in a third reworking of the material by ABC that produced ''[[Strange New World (film)|Strange New World]].''<ref>Alexander, David, "Star Trek Creator." ROC Books, an imprint of Dutton Signet, a division of Penguin Books USA, New York, June 1994, {{ISBN|0-451-45418-9}}, pp. 398–403.</ref> He began developing ''MAGNA I,'' an underwater science-fiction series, for [[20th Century Fox Television]]. By the time the work on the script was complete, though, those who had approved the project had left Fox and their replacements were not interested in the project. A similar fate was faced by ''Tribunes,'' a science-fiction police series, which Roddenberry attempted to get off the ground between 1973 and 1977. He gave up after four years;<ref>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 67</ref> the series never even reached the pilot stage.{{Citation needed|date=August 2019}} |

|||

"Star Trek New Voyages: Phase II" (10 episodes ) |

|||

... aka "Star Trek: New Voyages" - USA (original title) |

|||

In 1974, Roddenberry was paid $25,000 by [[John Whitmore (racing driver)|John Whitmore]] to write a script called ''The Nine''.<ref name=nine/> Intended to be about [[Andrija Puharich]]'s parapsychological research, it evolved into a frank exploration of his experiences attempting to earn a living attending science fiction conventions.<ref name=hise59>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 59</ref> At the time, he was again close to losing his house because of a lack of income.<ref name=nine>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=165}}</ref> The pilot ''[[Spectre (1977 film)|Spectre]],'' Roddenberry's 1977 attempt to create an [[Occult detective fiction|occult detective]] duo similar to [[Sherlock Holmes]] and [[Dr. Watson]],<ref name=hise68>[[#vanhise1992|Van Hise (1992)]]: p. 68</ref> was released as a television movie within the United States and received a limited theatrical release in the United Kingdom.<ref>{{cite web|title=A new Trek? Roddenberry's failed TV pilots (video)|url=http://www.blastr.com/2009/10/a_new_trek_roddenberrys_f.php|publisher=blastr|access-date=March 15, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160315182604/http://www.blastr.com/2009/10/a_new_trek_roddenberrys_f.php|archive-date=March 15, 2016|date=December 14, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

#Come What May (16 January 2004) - Writer (creator: "Star Trek") |

|||

#In Harms Way (8 October 2004) - Writer (creator: "Star Trek") |

|||

#Center Seat (17 March 2006) - Writer (creator: "Star Trek") |

|||

#To Serve All My Days (23 November 2006) - Writer (creator: "Star Trek") |

|||

#World Enough and Time (23 August 2007) - Writer (creator: "Star Trek") |

|||

#Blood and Fire: Part One (20 December 2008) - Writer (creator: "Star Trek") |

|||

#Blood and Fire: Part Two (20 November 2009) - Writer (creator) |

|||

#Enemy: Starfleet! (15 April 2011) - Writer (creator) |

|||

#The Child (2 April 2012) - Writer (creator) |

|||

#Kitumba (31 October 2013) - Writer (creator) |

|||

===''Star Trek'' revival=== |

|||

[[File:Space shuttle enterprise star trek-cropcast.jpg|left|thumb|Roddenberry (third from the right) in 1976 with most of the cast of ''Star Trek'' at the rollout of the [[Space Shuttle]] [[Space Shuttle Enterprise|''Enterprise'']] at the [[Rockwell International]] plant in [[Palmdale, California]]]] |

|||

... aka "Enterprise" - USA (original title) |

|||

Lacking funds in the early 1970s, Roddenberry was unable to buy the full rights to ''Star Trek'' for $150,000 (${{Inflation|US|.15|1970|r=2}} million in {{Inflation/year|US}}) from Paramount. [[Lou Scheimer]] approached Paramount in 1973 about creating an animated ''Star Trek'' series.<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=150}}</ref> Credited as "executive consultant" and paid $2,500 per episode, Roddenberry was granted full creative control of ''[[Star Trek: The Animated Series]]''. Although he read all the scripts and "sometimes [added] touches of his own", he relinquished most of his authority to ''de facto'' showrunner/associate producer D. C. Fontana.<ref>[[#clark2012|Clark (2012)]]: p. 323</ref> |

|||

Roddenberry had some difficulties with the cast. To save money, he sought not to hire George Takei and Nichelle Nichols. He neglected to inform Leonard Nimoy of this and instead, to get him to sign on, told him that he was the only member of the main cast not returning. After Nimoy discovered the deception, he demanded that Takei and Nichols play Sulu and Uhura when their characters appeared on screen; Roddenberry acquiesced. He had been promised five full seasons of the new show but ultimately, only one and a half were produced.<ref>{{harvp|Engel|1994|p=158}}</ref> |

|||

#Broken Bow: Part 1 (25 September 2001) - Writer (Star Trek creator) |

|||

#Broken Bow: Part 2 (26 September 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Fight or Flight (3 October 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Strange New World (10 October 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Unexpected (17 October 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Terra Nova (24 October 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Andorian Incident (31 October 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Breaking the Ice (7 November 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Civilization (14 November 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Fortunate Son (21 November 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Cold Front (28 November 2001) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Silent Enemy (16 January 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Dear Doctor (23 January 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Sleeping Dogs (30 January 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Shadows of P'Jem (6 February 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Shuttlepod One (13 February 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Fusion (27 February 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Rogue Planet (20 March 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Acquisition (27 March 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Oasis (3 April 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Detained (24 April 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Vox Sola (1 May 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Desert Crossing (8 May 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Fallen Hero (8 May 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Two Days and Two Nights (15 May 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Shockwave: Part 1 (22 May 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Shockwave: Part 2 (18 September 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Carbon Creek (25 September 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Minefield (2 October 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Dead Stop (9 October 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#A Night in Sickbay (16 October 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Marauders (30 October 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Seventh (6 November 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Communicator (13 November 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Singularity (20 November 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Vanishing Point (27 November 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Precious Cargo (11 December 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Catwalk (18 December 2002) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Dawn (8 January 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Stigma (5 February 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Cease Fire (12 February 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Future Tense (19 February 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Canamar (26 February 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Crossing (2 April 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Judgment (9 April 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Horizon (16 April 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Breach (23 April 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Cogenitor (30 April 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Regeneration (7 May 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Bounty (14 May 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#First Flight (14 May 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Expanse (21 May 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Xindi (10 September 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Anomaly (17 September 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Extinction (24 September 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Rajiin (1 October 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Impulse (8 October 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Exile (15 October 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Shipment (22 October 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Twilight (5 November 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#North Star (12 November 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Similitude (19 November 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Carpenter Street (26 November 2003) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Chosen Realm (14 January 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Proving Ground (21 January 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Stratagem (4 February 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Harbinger (11 February 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Doctor's Orders (18 February 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Hatchery (25 February 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Azati Prime (3 March 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Damage (21 April 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Forgotten (28 April 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#E² (5 May 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Council (12 May 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Countdown (19 May 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Zero Hour (26 May 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Storm Front: Part 1 (8 October 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Storm Front: Part 2 (15 October 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Home (22 October 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Borderland (29 October 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Cold Station 12 (5 November 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Augments (12 November 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#The Forge (19 November 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Awakening (26 November 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||

#Kir'Shara (3 December 2004) - Writer (creator "Star Trek") |

|||