Rising Sun Flag: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 1010034433 by NettingFish15019 (talk) |

|||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

It was originally used by [[daimyō|feudal warlords]] in Japan during the [[Edo period]] (1603–1868 CE).<ref name="rising-sun-flag-edo">{{cite web| url=http://www.japanvisitor.com/japanese-culture/japanese-symbols| title= Japanese Symbols| publisher=Japan Visitor/Japan Tourist Info| access-date=October 9, 2014}}</ref> |

It was originally used by [[daimyō|feudal warlords]] in Japan during the [[Edo period]] (1603–1868 CE).<ref name="rising-sun-flag-edo">{{cite web| url=http://www.japanvisitor.com/japanese-culture/japanese-symbols| title= Japanese Symbols| publisher=Japan Visitor/Japan Tourist Info| access-date=October 9, 2014}}</ref> |

||

On May 15, 1870, as a policy of the [[Meiji government]], it was adopted as the war flag of the [[Imperial Japanese Army]], and on October 7, 1889, it was adopted as the [[naval ensign]] of the [[Imperial Japanese Navy]].<ref>{{cite web | title=船舶旗について | url=http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/repository/81005923.pdf | publisher=Kobe University Repository:Kernel | access-date=October 18, 2014}}</ref> A modified flag is flown by the [[Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force]] and a different version is flown by the [[Japan Self-Defense Forces]] and the [[Japan Ground Self-Defense Force]]. |

On May 15, 1870, as a policy of the [[Meiji government]], it was adopted as the war flag of the [[Imperial Japanese Army]], and on October 7, 1889, it was adopted as the [[naval ensign]] of the [[Imperial Japanese Navy]].<ref>{{cite web | title=船舶旗について | url=http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/repository/81005923.pdf | publisher=Kobe University Repository:Kernel | access-date=October 18, 2014}}</ref> A modified flag is flown by the [[Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force]] and a different version is flown by the [[Japan Self-Defense Forces]] and the [[Japan Ground Self-Defense Force]]. |

||

The flag is controversial in parts of East Asia, especially [[South Korea]], due to the flag's significant usage as a symbol of [[Japanese imperialism]] during the [[Second World War]].<ref>{{Cite web|last=Goh|first=Da-Sol|date=2019-12-24|title=Why Koreans want worldwide ban on Rising Sun flag|url=https://asiatimes.com/2019/12/why-koreans-are-calling-for-the-world-to-stop-using-rising-sun-flag/|access-date=2021-01-20|website=Asia Times|language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=2019-10-29|title=South Korea compares Japan's 'rising sun' flag to swastika as Olympic row deepens|url=http://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/29/south-korea-compares-japans-rising-sun-flag-to-swastika-as-olympic-row-deepens|access-date=2021-01-20|website=the Guardian|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

== History and design == |

== History and design == |

||

Revision as of 14:03, 3 March 2021

The Rising Sun Flag (旭日 旗, Kyokujitsu-ki) symbolizes the sun as the Japanese national flag does. This design has been widely used in Japan for a long time. The design of the Rising Sun Flag is seen in numerous scenes in daily life of Japan, such as in fishermen's banners hoisted to signify large catch of fish, flags to celebrate childbirth, and in flags for seasonal festivities.[1]

It was originally used by feudal warlords in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1868 CE).[2] On May 15, 1870, as a policy of the Meiji government, it was adopted as the war flag of the Imperial Japanese Army, and on October 7, 1889, it was adopted as the naval ensign of the Imperial Japanese Navy.[3] A modified flag is flown by the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force and a different version is flown by the Japan Self-Defense Forces and the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force.

History and design

War flag of the Imperial Japanese Army (1870–1945)

War flag of the Imperial Japanese Army (1870–1945)

Naval ensign, flown by ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1889–1945). Flag ratio: 2:3.

Naval ensign, flown by ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1889–1945). Flag ratio: 2:3.The flag of Japan and the rising Sun had symbolic meaning since the early 7th century in the Asuka period (538–710 CE). The Japanese archipelago is east of the Asian mainland, and is thus where the Sun "rises". In 607 CE, an official correspondence that began with "from the Emperor of the rising sun" was sent to Chinese Emperor Yang of Sui.[4] Japan is often referred to as "the land of the rising sun".[5] In the 12th-century work, The Tale of the Heike, it was written that different samurai carried drawings of the Sun on their fans.[6]

The Japanese word for Japan is 日本, which is pronounced Nihon or Nippon and literally means "the origin of the sun". The character nichi (日) means "sun" or "day"; hon (本) means "base" or "origin".[7] The compound therefore means "origin of the sun" and is the source of the popular Western epithet "Land of the Rising Sun".[8] The red disc symbolizes the Sun and the red lines are light rays shining from the rising sun.

The design of the Rising Sun Flag (Asahi) has been widely used since ancient times, and a part of it was called "Hiashi" (日足, ひあし) and used as the samurai's crest ("Hiashimon", 日足紋).[9][10] The flag was especially used by samurai in the Kyushu region. Examples include the "Twelve-day legs" (変わり十二日足) of the Ryūzōji clan (1186–1607 CE) in Hizen Province and the Kusano clan (草野氏) in Chikugo Province and the "eight-day legs" (八つ日足紋) of the Kikuchi clan (1070–1554 CE) in Higo Province. There is a theory that in many parts of the Kyushu region, Hizen and Higo are related to what was called "the country of Japan (Hi)".[11][注 1]

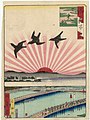

There have been many types of Asahi flags since ancient times, and the design in which light rays spread in all directions without clouds expresses honored day or auspicious events (ハレ), and was a design that was used for celebrate a good catch, childbirth and seasonal festivitivals.[12][13][14] A well-known variant of the flag of the sun disc design is the sun disc with 16 red rays in a Siemens star formation. The Rising Sun Flag (旭日 旗, Kyokujitsu-ki) has been used as a traditional national symbol of Japan since at least the Edo period (1603 CE).[2] It is featured in antique artwork such as ukiyo-e prints through history, such as the Lucky Gods' visit to Enoshima, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Yoshiiku in 1869 and One Hundred Views of Osaka, Three Great Bridges, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kunikazu in 1854. The Fujiyama Tea Co. used it as a wooden box label of Japanese tea (green tea) for export in the Meiji period / Taisho period (1880s).[15]

It was historically used by the daimyō (大名) and Japan's military, particularly the Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy. The ensign, known in Japanese as the Jyūrokujō-Kyokujitsu-ki (十六条旭日旗), was first adopted as the war flag on May 15, 1870, and was used until the end of World War II in 1945. It was re-adopted on June 30, 1954, and is now used by the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF). The Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) and Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF) use a variation of the Rising Sun Flag with red, white and gold colors.[16]

The design is similar to the flag of Japan, which has a red circle in the center signifying the Sun. The difference compared to the flag of Japan is that the Rising Sun Flag has extra sun rays (16 for the ensign) exemplifying the name of Japan as "The Land of the Rising Sun". The Imperial Japanese Army first adopted the Rising Sun Flag in 1870.[17] The Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy both had a version of the flag; the naval ensign was off-set, with the red sun closer to the lanyard side, while the army's version (which was part of the regimental colors) was centered. The flags were used until Japan's surrender in World War II during August 1945. After the establishment of the Japan Self-Defense Forces in 1954, the off-set Rising Sun Flag was re-adopted for the JMSDF and a new 8-rays Rising Sun Flag with a yellow border for the JGSDF and JSDF was approved by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP/GHQ). The flag with the off-set sun and 16 rays is the ensign of the Maritime Self-Defense Force, but it was modified with a different color red. The old flag is darker red (RGB #b12d3d) and the post-WW2 modified version is brighter red (RGB #bd0029).[18]

The Imperial Japanese Army flag with symmetrical 16 rays and a 2:3 ratio was abolished. The Japan Self-Defense Forces and the Ground Self-Defense Force use a significantly different Rising Sun Flag with 8-rays and an 8:9 ratio. The edges of the rays are asymmetrical since they form angles 19, 21, 26 and 24 degrees. It also has indentations for the yellow (golden) irregular triangles along borders. The JSDF Rising Sun Flag was adopted by a law/order/decree published in the Official Gazette of June 30, 1954.[18]

Regardless of the military flag, before the Meiji period, the design of Asahi was used for prayers, festivals, celebration events, reconstruction, logos of companies and products, big catch flags (Tairyō-bata), corporate and product logos and sports.[19][20][21][22][23][24]

Present-day use

The Japanese naval ensign, which is flown by ships of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (established in 1954). It uses a 2:3 ratio.

The Japanese naval ensign, which is flown by ships of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (established in 1954). It uses a 2:3 ratio.

The flag of the Japan Self-Defense Forces and the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (established in 1954)

The flag of the Japan Self-Defense Forces and the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (established in 1954)Commercially the Rising Sun Flag is used on many products, designs, clothing, posters, beer cans (Asahi Breweries), newspapers (Asahi Shimbun), bands, manga, comics (e.g., Fantastic Four/Iron Man: Big in Japan, June 2006), anime, movies, video games (e.g., E. Honda's stage of Street Fighter II), etc.[25] The Rising Sun Flag appears on commercial product labels, such as on the cans of one variety of Asahi Breweries lager beer.[25] The design is also incorporated into the logo of the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun. Among fishermen, the tairyō-ki (大漁旗, "Good Catch Flag") represents their hope for a good catch of fish. Today it is used as a decorative flag on vessels as well as for festivals and events. The Rising Sun Flag is used at sporting events by the supporters of Japanese teams and individual athletes as well as by non-Japanese.[26]

Since June 30, 1954, the Rising Sun Flag has been the war flag and naval ensign of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF). JSDF Chief of Staff Katsutoshi Kawano said the Rising Sun Flag is the Maritime Self-Defense Force sailors' "pride".[27] The Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) and the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF) use the Rising Sun Flag with eight red rays extending outward, called Hachijō-Kyokujitsuki (八条旭日旗). A gold border lies partially around the edge.[16]

The flag is also used by non-Japanese, for example, in the emblems of some U.S. military units based in Japan, and by the American blues rock band Hot Tuna, on the cover of its album Live in Japan. It is used as an emblem of the United States Fleet Activities Sasebo, as a patch of the Strike Fighter Squadron 94, a mural at Misawa Air Base, the former insignia of Strike Fighter Squadron 192 and Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System with patches of the 14th Fighter Squadron. Some extreme right-wing groups display it at political protests.[28]

Controversy

As the flag was used by the Imperial Japanese military during Japan's actions during World War II, it is regarded as offensive by some in East Asia, particularly in South Korea[29][30] (which was ruled by Japan) and China.[31] This symbol is often associated with Japanese imperialism in the early 20th century in these two countries.[32][33]

South Korea hosted an international fleet review at Jeju Island from October 10 to 14, 2018. South Korea requested all participating countries to display only their national flags and the South Korean flag on their vessels. Japan balked at the demand, with the then-Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera, since replaced, claiming the display of the Rising Sun Flag should be mandatory under Japanese law. South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha urged Japan to be more considerate about Japan's former rule of the Korean Peninsula and stated that her ministry will review "possible and appropriate options" before deciding to take stronger international actions when asked whether South Korea could raise the issue with the United Nations.[34] Japan announced on October 5, 2018, that it will be withdrawing from the fleet review because it could not accept Seoul's request to remove the Rising Sun Flag. The Defense Minister notified the South Korean government of its decision. Both nations reiterated the need for continued defense cooperation.[35] When the JMSDF was established in 1954, it adopted the Rising Sun Flag (Kyokujitsu-ki) as its ensign to show the nationality of its ships. It was approved by GHQ/SCAP. On September 28, 2018, an official of Japan's Ministry of Defense said that the South Korean navy's request lacks common sense and that they would not partake in a fleet review, since no country would follow such a request.[36] On October 6, 2018, JSDF Chief of Staff Katsutoshi Kawano said the Rising Sun Flag is the Maritime Self-Defense Force sailors' "pride" and that the JMSDF would absolutely not go if they had to remove the flag.[27][37]

Critic Katsumi Murotani, a correspondent of the Jiji Newsletter Seoul in the 1980s, stated that the Rising Sun Flag was not criticized until recently in South Korea.[38][39] South Korea did not object to Japan's adoption of the Rising Sun Flag for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force in 1952, nor to the entry into South Korean ports Japanese warships flying the flag on a warship at the 1998 and 2008 navy fleet review held in South Korea.[40]

South Korean campaigns against the Rising Sun Flag began in 2011 when a South Korean footballer Ki Sung-yueng was accused of making a racist gesture, which he defended claiming he was annoyed at having seen a Rising Sun Flag in the stadium.[41] In 2012, South Koreans who disapproved of the flag began to refer to it as a "war crime flag".[42][43]

According to political scientist Kan Kimura, in 2012, following Ki Sung-yeon's remarks, Koreans living in New York formed a political group "The Citizens Against War Criminal Symbolism" and started a campaign to identify the Rising Sun Flag with the Nazi swastika and ban it. Then, at the 2013 EAFF East Asian Cup, a banner with a slogan about historical issues with Japan appeared on the Korean cheering squad. As these events were often reported in the Korean media, an international political movement among Koreans to equate the Rising Sun Flag with that of the Nazi swastika and to prohibit it intensified.[44]

The Sankei Shimbun criticized South Korea's attitude toward the Rising Sun Flag, stating that even the United States, who was Japan's opponent during World War II, has not protested formally against the Rising Sun Flag.[45][46] The president of the Sankei Shimbun Minagawa Hoshi said the corporate logo flag of the Rising Sun Flag design of the Asahi Shimbun, which is praised for being conscientious in South Korea,[47] never had any such issues.[48]

On August 19, 2019, the American model and singer Charlotte Kemp Muhl uploaded a photo wearing a T-shirt design with the Rising Sun Flag on Instagram. She was criticized for this by Korean Internet commenters, who compared the flag's symbolic significance to that of the German Nazi flag.[citation needed] Muhl responded that the flag "was first used by the Japanese during the Meiji era...before the Korean colonial rule," and therefore its usage should not necessarily be interpreted as indicating support of Imperial Japan or its rule over Korea.[citation needed] Sean Lennon, Muhl's romantic partner (and son of John Lennon), defended her use of the symbol, stating: “You have to be free to use symbolic things."[49][50]

The South Korean parliamentary committee for sports asked the organizers of the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo to ban the Rising Sun Flag. According to South Korean lawmaker An Min-suk, it could not be a peaceful Olympics with the flag in the stadium. The organizers refused to ban the flag from venues.[51][52] In September 2019, the Chinese Civil Association for Claiming Compensation from Japan sent a letter to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to ban the flag.[53][dead link] According to the Associated Press, the IOC confirmed the receipt of the letter and said in a statement "sports stadiums should be free of any political demonstration. When concerns arise at games time we look at them on a case by case basis."[54] A history professor at the University of Connecticut, Alexis Dudden, however, pointed out that "too few survivors of Japan's wartime atrocities remain alive to fill the Olympic stadium and explain the meaning of this symbol and the International Olympic Committee must learn from history instead."[55]

The Japanese government's basic position on the Rising Sun Flag is that "claims that the flag is an expression of political assertions or a symbol of militarism are absolutely false."[56] Dudden counters that "Japanese historians, activists and regular citizens have resisted the efforts of their own government to deny Japanese history, by continuing to dig up bones and government documents, and recording the oral testimonies of those who suffered during Japan's imperial occupations"[57] However, the same could be said about the British, French and other flags that were used during colonialism. The rising sun motif was also used in Chinese art, posters and statues during the post-war Mao Zedong era. The Sankei Shimbun counters, the rising sun flag's history dates back much further than World War 2.[58] The Japanese Vexillological Association states it was designed for the Japanese army in the early Meiji period and a different version was adopted by naval forces.[58] The Japanese Vexillological Association states “Flags used by the military are domestic decisions.”[58] Therefore: “Normally other countries do not raise objections. The Rising Sun flag existed before Japan went to war and the nature of the issue is different from that of the swastika flag, which was created to symbolize the Nazi regime’s political ideologies.”[58] Former Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida stated: “There is no country in the world that does not know this flag. The flag can be recognized as Japan’s in any sea.” Due to its recognizability it was adopted as the naval flag of the JMSDF “There is no problem as the Self-Defense Forces law regulated the use of the flag.”[58] The rising sun flag has multiple meanings and also serves other purposes: “The rising-sun design is beautiful, and its motif holds a celebratory impression. From before the war, the flag was widely used by fishermen to indicate a rich haul or to celebrate birth and seasonal festivals. The customs are carried out to this day.”[58] Japanese history professor Masao Shimojo at Takushoku University, points out that criticism of the rising sun flag is caused by activists to instigate anti-Japanese sentiment.[58]

Examples of the Rising Sun design in use

Art

-

Lucky Gods' visit to Enoshima, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Yoshiiku, 1869

-

One Hundred Views of Osaka, Three Great Bridges, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kunikazu, 1854. The composition of the morning sun rising behind the Nanhwa Three Bridge.

-

From "Good and evil child's hand", " Kiyomori entrance" (Adachi Ginbo, 1885)

-

"Fugitoshi Fish Entering" (author unknown, 19th-century Edo period)

-

The postcard of anti Tuberculosis groups in Japan (June 27, 1925)

-

Suehiro Tokyo sights - the Edobashi office of Communications and Transportation (1882)

Products

-

Tairyō-bata is a traditional Japanese fisherman's flag. Today it is used as a decorative flag on vessels and for festivals and events.

-

Postcard of a Japanese woman draped in the rising sun flag of Japan (1910).

-

Flag of the Asahi Shimbun Company since 1889

-

Asahi Gold Beer

-

Asahi Beer poster. The Asahi logo is on the bottle label (in 2013, at a pub in Higashiosaka city).

-

Wooden box label (Fujiyama Tea Co.) of Japanese tea (green tea) for export in the Meiji / Taisho period. Such a label was called orchid.

-

"Yamagata phone launch anniversary" postcard (Yamagata post office, 1907). Telephone exchange service began in Yamagata on November 26, 1868.

-

Japan raw silk pack sticker (in French and Japanese) (1880)

Sports

-

Japanese footballing fans wave a Rising Sun Flag during a Japan vs. Bosnia and Herzegovina match in January 2008.

-

Japanese athlete Kinue Hitomi at the 1928 Summer Olympics

-

Sumo wrestler Asashio Tarō I with rising sun waves kesho mawashi, 1901

Japan Self-Defense Forces

-

Viewing march by JGSDF regiment vehicle troops with the flag of the Japan Self-Defense Forces

-

Ground Self-Defense Force Utsunomiya gemstone site commemorative event with the Self-Defense Forces flag

-

Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force members of the crew of JDS Kongō

-

An SM-3 (Block 1A) missile is launched from the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyer JS Kirishima.

-

Self-Defense Forces flag of the JGSDF 46th Infantry Regiment

United States military

-

Emblem of United States Fleet Activities Sasebo

-

Patch of Strike Fighter Squadron 94

-

Emblem of U.S. Army Aviation Battalion Japan

-

The mural painted on a wall at Misawa Air Base, Japan

-

Former insignia of Strike Fighter Squadron 192

-

Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System with patches of the 14th Fighter Squadron

Similar designs

Internationally, similar designs with the rays of the sun are frequently used as national flags and military flags.[59] In the eastern countries, mainly in China and the Soviet Union, it was often used as a symbol of Marxist–Leninism and socialist ruralism in posters and the like.

United States

-

Flag of Arizona

It was established as the state flag in 1917.[59]

People's Republic of China

A number of propaganda posters with the Asahi pattern centered on Mao Zedong were produced and published and advertised throughout the country. It is pointed out that Mao Zedong liked the Asahi pattern very much. In the People's Republic of China, the Asahi design has a long history of being actively used by the Communist Party of China.[60]

North Macedonia

The flag of the Republic of North Macedonia has a design similar to that of the Asahi Flag. Originally, when it became independent from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, it used a design called the Vergina star for its flag, but this led to a controversy with the Hellenic Republic, which used this design for the flag of its Macedonia region. It was changed to the current national flag in 1995 (Heisei 7).[59]

-

Current flag of the Republic of North Macedonia

-

Old flag of the Republic of Macedonia (1991–1995)

-

Flag of Greek Macedonia

Ukraine

The state flag of Donetsk Oblast is a sunrise design similar to the Rising Sun Flag.

-

Donetsk Oblast state flag

Belarus

The ensign of the Belarusian Air Force has the Order of the Rising Sun pattern.

-

Flag of the Belarusian Air Force

Venezuela

The flag of Lara state was enacted in 1901.[59]

-

Venezuela Lara (state) flag

Karen Liberation Army

The Karen National Liberation Army, established in 1949 in Myanmar (Burma), uses a design similar to the Asahi flag for the military flag.

-

Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) flag

-

Karen National Union (KNU) flag

Tibet and the Tibetan government in exile

The government of Tibet Ganden Phodrang enacted a national flag of Tibet in 1912. It is said that this was indirectly influenced by the "Asahi Sun Flag, the military flag of the Imperial Army", because a Japanese researcher and monk Aoki Bunkyo was involved in the design. ("Place a rising sun that reveals half of the Japanese flag", "This new flag sometimes looks like a Japanese flag in the wind, so it had to be revised further").[61]) After the People's Republic of China's invasion of Tibet in 1949, China positioned Gandempotan as the local government of Tibet, which continued to use it as a flag of Tibet. In 1959, Ganden Potan, led by Dalai Lama XIV, escaped Tibet and the government was reorganized in India as the Tibetan government in exile. The Tibetan government has used the flag as its national flag to date.

-

Flag of Tibet

Soviet Union

The design was used for flags of the Soviet Air Forces, founded on December 20, 1917, in the Soviet Union and flags of the Georgian Republic established in 1921 in the Soviet Constituent Republic, etc.

-

Flag of the Soviet Air Force

-

Russian Air Force military flag. Design changes based on Soviet Air Force era flag.

-

Flag of Georgia. After independence from the Soviet Union, the flag was changed with a completely different design (Georgian flag).

Unification Church

Korea's emerging religions organization Unification movement (formerly: Unification Church) has incorporated Asahi in its logo since it was established in 1954. On May 1, 1994, it was changed to another logo with the name change to the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification.[62][63]

-

First Unification Church symbol (1954–1997)

See also

References

- ^ "The Rising Sun Flag As Part Of Japanese Culture" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. November 8, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "Japanese Symbols". Japan Visitor/Japan Tourist Info. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "船舶旗について" (PDF). Kobe University Repository:Kernel. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ Dyer 1909, p. 24

- ^ Edgington 2003, pp. 123–124

- ^ Itoh 2003, p. 205

- ^ "Where does the name Japan come from?". Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Piggott, Joan R. (1997). The emergence of Japanese kingship. Stanford University Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-8047-2832-4.

- ^ 播磨屋.com 日足紋章

- ^ 家紋の由来

- ^ 見聞諸家紋

- ^ 韓国世論「旭日旗とナチス党旗を同一視」の大いなる誤解 サーチナ 2013年4月16日

- ^ 中国においても、広東語で通勝と称される中国古来の黄暦には、古くから春牛図が描かれており、その図中の日の意匠は日本の旭日に類似していた(豊作祈願)芒神春牛圖

- ^ Rising Sun Flag Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

- ^ Designer Idezaka (September 9, 2013). 浮世絵と西洋の出合い 戦前の輸出茶ラベルの魅力 [Ukiyo-e and Western encounter The charm of the exported tea label before the war]. Nikkei Style (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ a b Government of Japan. 自衛隊法施行令 [Self-Defense Forces Law Enforcement Order]; June 3, 1954 [Retrieved January 25, 2008]. (in Japanese).

- ^ "海軍旗の由来". kwn.ne.jp. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ a b Phil Nelson; various. "Japanese military flags". Flags of the World. Flagspot.

- ^ "神戸新聞NEXT|淡路|新造船、鮮やか大漁旗まとい進水式 淡路市". www.kobe-np.co.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "天然マダイ船12年ぶり進水 糸島の船越漁港". 西日本新聞Web (in Japanese). Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "【オリックス】新守護神・増井、「大漁旗」モチーフ応援グッズ発売". スポーツ報知 (in Japanese). April 3, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "オリックス増井応援グッズは故郷焼津市の大漁旗原案 – プロ野球 : 日刊スポーツ". nikkansports.com (in Japanese). Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "宗像大社みあれ祭:大漁旗はためかせパレード – 毎日新聞". 毎日新聞 (in Japanese). Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "<塩釜みなと祭>震災と豪雨復興願う 御座船、松島湾巡る「頑張ろう西日本!」掲げた船も". 河北新報オンラインニュース (in Japanese). Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ a b "Asahi Beer New Design". Japan Visitor Blog. December 12, 2011.

- ^ "A great decade for Japan". FIFATV. December 1, 2012.

- ^ a b "Japan to skip S. Korea fleet event over 'rising sun' flag". The Asahi Shimbun. October 6, 2018. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "World: Asia-Pacific Reprise for Japan's anthem". BBC News. August 15, 1999.

- ^ http://www.manilastandard.net/news/national/333757/-rising-sun-art-sets-off-bashing.html

- ^ http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/hashtag/content/754837/here-s-why-cancelkorea-is-trending-on-twitter/story/

- ^ Taylor, Adam (June 2, 2015). "Japan has a flag problem, too". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Korean lawmakers adopt resolution calling on Japan not to use rising sun flag". Korea Herald. August 29, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Bill McMichael (August 2, 2011). "That Flag". Navy Times Scoop Deck.

- ^ "S. Korea renews call for Japan to remove 'rising sun' flag".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[dead link] - ^ Takeda, Hajimu (September 28, 2018). "S. Korea wants MSDF to lower 'kyokujitsuki' flag in review". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/east-asia/article/2167441/japan-pulls-out-south-korea-naval-drills-over-demands-it-remove

- ^ ‘영국에서도 욱일기가?’ 日, 욱일기 흔든 사례보니…일간스포츠 中央日報 2013年7月31日

- ^ 「日本は意味分かっている」 旭日旗使用で韓国外務省 共同通信 2013年8月2日

- ^ "[특파원 칼럼] 대일외교, '감정'보다 '사실' 앞세워야" [Foreign diplomacy, Put forward "fact" rather than "emotion"]. Korea Economic Daily. October 12, 2018.

- ^ "「旭日旗」問題の契機はサッカー・アジア杯 奥薗静岡県立大准教授" [Rising Sun Flag controversy began at an Asian Cup Football match – Associate Professor of the University of Shizuoka Okuzono]. Sankei Shimbun. October 5, 2018. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018.

- ^ "[Why] 욱일기 때문에 불참통보한 일본군함, 우린 왜 지금 더 분노하나" [[Why] The Japanese warship conveyed an absence. Why are we angry now?]. The Chosun Ilbo. October 6, 2018. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018.

- ^ "[팩트체크] 욱일기는 전범기? '전범기'는 없다" [[Fact check] Rising Sun Flag is war crime flag? There is no "war crime flag"]. News True or Fake. October 6, 2018.

In the picture above, the word "war crime flag" was first used in Korea in August 2012.

- ^ Kan Kimura. "New Aspects of Korean Nationalism Seen in the Rising Sun Flag Problem" (PDF). Journal of International Cooperation Studies, Vol.27, No.1. pp. 31–37. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ 韓国の反日から旭日旗の名誉を守れ (第三段 国際社会は受け入れ) 産経新聞 2013年8月3日

- ^ "日本の艦艇、旭日旗を掲げて韓国に入港し物議=韓国ネット「...|". レコードチャイナ. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ "日우파기자가 밝힌 우파들의 본심" [Real intention of the rightist revealed by a Japanese rightist reporter]. The Chosun Ilbo.

- ^ 皆川豪志. "なぜ韓国人は、朝日の社旗に怒らないのか,繰り返されるマッチポンプ". iRONNA. 産経デジタル. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ 2019年8月23日 レコードチャイナ 旭日旗Tシャツを着た米モデル、韓国人からの指摘を一蹴「退屈で虚しい論争」

- ^ 2019年8月22日 SBSニュース 米国のモデル、戦犯旗のTシャツを着てネチズンと「舌戦」(韓国語)

- ^ "'Symbol of the devil': Why South Korea wants Japan to ban the Rising Sun flag from the Tokyo Olympics". September 7, 2019.

- ^ "Democratic Party lawmaker proposes resolution opposing Rising Sun Flag in Ntl. Assembly". October 2, 2019.

- ^ "China group asks IOC to ban 'rising sun' flag at Tokyo Olympics". September 2, 2019.

- ^ "S. Korea urges IOC to ban Japanese imperial flag from 2020 Olympics". Kyodo News. September 12, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "Japan's rising sun flag has a history of horror. It must be banned at the Tokyo Olympics". The Guardian. November 1, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "Rising Sun Flag: Japan's basic position (Press Conference by the Chief Cabinet Secretary SUGA, September 26, 2013(AM))". MOFA, Japan. November 8, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "Japan's rising sun flag has a history of horror. It must be banned at the Tokyo Olympics". The Guardian. November 1, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Why the Uproar Over Japan's Rising Sun Flag? It's A Symbol for Celebrating Life and Bounty". Sankei Shimbun, Japan Forward. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c d 世界で広く使用されている旭日のデザイン 日本国外務省

- ^ 赤い中国消滅:張子の虎の内幕p126,陳破空

- ^ 青木文教 『祕密之國 西藏遊記』 内外出版、1920年(大正9年)10月19日、近代デジタルライブラリー

- ^ 統一教会とは <マークの意味>

- ^ 世界平和統一家庭連合 藤沢家庭教会<マークの意味>

- ^ Note: in modern times, it is also used as a simple pattern, for example, Yurikamome Inc. (company), Hinode Station pattern.

External links

Media related to Rising Sun Flag of Japan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rising Sun Flag of Japan at Wikimedia Commons- "The Rising Sun Flag As Part Of Japanese Culture" Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan