Thinking outside the box: Difference between revisions

Add History section. Start cleaning up article to make it more coherent. |

Remove duplicate part; remove original unattested research from almost 10 years ago |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

The origin of the phrase is unclear. An early allusion is a 1969 newspaper article by [[Norman Vincent Peale]], quote:<ref>{{cite news |last=Peale |first=Norman Vincent |date=1969-10-25 |title=Blackmail Is the Problem |publisher=Chicago Tribune |page=[https://newspaperarchive.com/chicago-tribune-oct-25-1969-p-13-335162371-fullpage.jpg 13] |author-link=Norman Vincent Peale| url=https://newspaperarchive.com/chicago-tribune-oct-25-1969-p-13-335162371-fullpage.jpg|url-access=subscription}}</ref> |

The origin of the phrase is unclear. An early allusion is a 1969 newspaper article by [[Norman Vincent Peale]], quote:<ref>{{cite news |last=Peale |first=Norman Vincent |date=1969-10-25 |title=Blackmail Is the Problem |publisher=Chicago Tribune |page=[https://newspaperarchive.com/chicago-tribune-oct-25-1969-p-13-335162371-fullpage.jpg 13] |author-link=Norman Vincent Peale| url=https://newspaperarchive.com/chicago-tribune-oct-25-1969-p-13-335162371-fullpage.jpg|url-access=subscription}}</ref> |

||

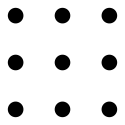

[[File:9dots.svg|thumb|right|The "nine dots" puzzle. The goal of the puzzle is to link all 9 dots using four straight lines or less, without lifting the pen. The solution is at the end of this article.]] |

|||

: There is one particular puzzle you may have seen. It's a drawing of a box with some dots in it, and the idea is to connect all the dots by using only four lines. You can work on that puzzle, but the only way to solve it is to draw the lines so they connect outside the box. It's so simple once you realize the principle behind it. But if you keep trying to solve it inside the box you'll never be able to master that particular puzzle. |

: There is one particular puzzle you may have seen. It's a drawing of a box with some dots in it, and the idea is to connect all the dots by using only four lines. You can work on that puzzle, but the only way to solve it is to draw the lines so they connect outside the box. It's so simple once you realize the principle behind it. But if you keep trying to solve it inside the box you'll never be able to master that particular puzzle. |

||

: |

: |

||

| Line 29: | Line 30: | ||

| image2 = Ninedots.svg |

| image2 = Ninedots.svg |

||

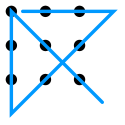

| alt2 = The solution |

| alt2 = The solution |

||

| footer = The goal of the puzzle (left) is to link all 9 dots using four straight lines or fewer, without lifting the pen |

| footer = The goal of the puzzle (left) is to link all 9 dots using four straight lines or fewer, without lifting the pen. All such answers (one example shown right) require the solver to draw a line that extends outside of the "box" formed by the grid. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The notion of something outside a perceived "box" is related to a traditional [[topography|topographical]] [[puzzle]] called the '''nine dots puzzle'''.<ref name=":0">Kihn, Martin. [http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/95/debunk.html "'Outside the Box': the Inside Story,"] ''FastCompany'' 1995</ref>{{failed verification|date=September 2020}} |

|||

The origins of the phrase "thinking outside the box" are obscure; but it was popularized in part because of a nine-dot puzzle, which [[John Adair (author)|John Adair]] claims to have introduced in 1969.<ref>{{cite book | last = Adair | first = John | title = The art of creative thinking how to be innovative and develop great ideas | url = https://archive.org/details/artcreativethink00adai | url-access = limited | publisher = Kogan Page | location = London Philadelphia | year = 2007 | isbn = 9780749452186 | page = [https://archive.org/details/artcreativethink00adai/page/n137 127] }}</ref> [[Management consultant]] Mike Vance has claimed that the use of the nine-dot puzzle in consultancy circles stems from the [[corporate culture]] of the [[Walt Disney Company]], where the puzzle was used in-house.<ref>[http://www.creativethinkingassoc.com/mikevance.html Biography of Mike Vance] at Creative Thinking Association of America.</ref>{{failed verification|date=September 2020}} |

|||

[[File:Eggpuzzle.jpg|thumb|''Christopher Columbus' Egg Puzzle'' as it appeared in [[Sam Loyd]]'s ''Cyclopedia of Puzzles'']] |

[[File:Eggpuzzle.jpg|thumb|''Christopher Columbus' Egg Puzzle'' as it appeared in [[Sam Loyd]]'s ''Cyclopedia of Puzzles'']] |

||

The nine dots puzzle is much older than the slogan. It appears in [[Sam Loyd]]'s 1914 ''Cyclopedia of Puzzles''.<ref>Sam Loyd, ''Cyclopedia of Puzzles''. (The Lamb Publishing Company, 1914)</ref> |

The nine dots puzzle is much older than the slogan "think outside the box". It appears in [[Sam Loyd]]'s 1914 ''Cyclopedia of Puzzles''.<ref>Sam Loyd, ''Cyclopedia of Puzzles''. (The Lamb Publishing Company, 1914)</ref> In the 1951 compilation ''The Puzzle-Mine: Puzzles Collected from the Works of the Late [[Henry Ernest Dudeney]]'', the puzzle is attributed to Dudeney himself.<ref>J. Travers, ''The Puzzle-Mine: Puzzles Collected from the Works of the Late Henry Ernest Dudeney''. (Thos. Nelson, 1951)</ref> Sam Loyd's original formulation of the puzzle<ref>[http://www.mathpuzzle.com/loyd/cop300-301.html Facsimile from ''Cyclopedia of Puzzles'' - Columbus's Egg Puzzle is on right-hand page]</ref> entitled it as "[[Christopher Columbus]]' egg puzzle." This was an allusion to the story of [[Egg of Columbus]]. |

||

The puzzle proposed an intellectual challenge—to connect the dots by drawing four straight, continuous lines that pass through each of the nine dots, and never lifting the pencil from the paper. The [[:wikt:conundrum|conundrum]] is easily resolved, but only by drawing the lines outside the confines of the square area defined by the nine dots themselves. The phrase "thinking outside the box" is a restatement of the solution strategy. The puzzle only seems difficult because people commonly imagine [[Convex hull|a boundary around the edge]] of the dot array.<ref>Daniel Kies, [http://papyr.com/hypertextbooks/comp2/9dots.htm "English Composition 2: Assumptions: Puzzle of the Nine Dots"], retr. Jun. 28, 2009.</ref> The heart of the matter is the unspecified barrier that people typically perceive. |

The puzzle proposed an intellectual challenge—to connect the dots by drawing four straight, continuous lines that pass through each of the nine dots, and never lifting the pencil from the paper. The [[:wikt:conundrum|conundrum]] is easily resolved, but only by drawing the lines outside the confines of the square area defined by the nine dots themselves. The phrase "thinking outside the box" is a restatement of the solution strategy. The puzzle only seems difficult because people commonly imagine [[Convex hull|a boundary around the edge]] of the dot array.<ref>Daniel Kies, [http://papyr.com/hypertextbooks/comp2/9dots.htm "English Composition 2: Assumptions: Puzzle of the Nine Dots"], retr. Jun. 28, 2009.</ref> The heart of the matter is the unspecified barrier that people typically perceive. |

||

Telling people to "think outside the box" does not help them think outside the box, at least not with the 9-dot problem.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Maier|first1=Norman R. F.|last2=Casselman|first2=Gertrude G. |title=Locating the Difficulty in Insight Problems: Individual and Sex Differences|journal=Psychological Reports|date=1 February 1970|volume=26|issue=1|pages=103–117|doi=10.2466/pr0.1970.26.1.103|pmid=5452584|s2cid=43334975}}</ref> This is due to the distinction between [[procedural knowledge]] (implicit or [[tacit knowledge]]) and [[declarative knowledge]] (book knowledge). For example, a non-verbal cue such as drawing a square outside the 9 dots does allow people to solve the 9-dot problem better than average.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Lung|first=Ching-tung|author2=Dominowski, Roger L. |title=Effects of strategy instructions and practice on nine-dot problem solving.|journal=Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition|date=1 January 1985|volume=11|issue=4|pages=804–811|doi=10.1037/0278-7393.11.1-4.804}}</ref> |

Telling people to "think outside the box" does not help them think outside the box, at least not with the 9-dot problem.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Maier|first1=Norman R. F.|last2=Casselman|first2=Gertrude G. |title=Locating the Difficulty in Insight Problems: Individual and Sex Differences|journal=Psychological Reports|date=1 February 1970|volume=26|issue=1|pages=103–117|doi=10.2466/pr0.1970.26.1.103|pmid=5452584|s2cid=43334975}}</ref> This is due to the distinction between [[procedural knowledge]] (implicit or [[tacit knowledge]]) and [[declarative knowledge]] (book knowledge). For example, a non-verbal cue such as drawing a square outside the 9 dots does allow people to solve the 9-dot problem better than average.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Lung|first=Ching-tung|author2=Dominowski, Roger L. |title=Effects of strategy instructions and practice on nine-dot problem solving.|journal=Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition|date=1 January 1985|volume=11|issue=4|pages=804–811|doi=10.1037/0278-7393.11.1-4.804}}</ref> |

||

The nine-dot problem is a well-defined problem. It has a clearly stated goal, and all necessary information to solve the problem is included (connect all of the dots using four straight lines, without removing the pen from the paper once you start drawing). Furthermore, well-defined problems have a clear ending (you know when you have reached the solution). Although the solution is "outside the box" and not easy to see at first, once it has been found, it seems obvious. Other examples of well-defined problems are the [[Tower of Hanoi]] and the [[Rubik's Cube]]. |

|||

In contrast, characteristics of ill-defined problems are:{{Citation needed|date=March 2022}} |

|||

*not clear what the question really is |

|||

*not clear how to arrive at a solution |

|||

*no idea what the solution looks like |

|||

An example of an ill-defined problem is "what is the essence of happiness?" The skills needed to solve this type of problem are the ability to reason and draw inferences, [[metacognition]], and [[epistemic]] monitoring.{{Citation needed|date=March 2022}} |

|||

===The single straight line solution=== |

===The single straight line solution=== |

||

Revision as of 16:49, 10 August 2022

It has been suggested that this article be split into a new article titled Nine dots puzzle. (discuss) (September 2020) |

| Part of a series on |

| Puzzles |

|---|

|

Thinking outside the box (also thinking out of the box[1][2] or thinking beyond the box and, especially in Australia, thinking outside the square[3]) is a metaphor that means to think differently, unconventionally, or from a new perspective. The phrase also often refers to novel or creative thinking.

History

The origin of the phrase is unclear. An early allusion is a 1969 newspaper article by Norman Vincent Peale, quote:[4]

- There is one particular puzzle you may have seen. It's a drawing of a box with some dots in it, and the idea is to connect all the dots by using only four lines. You can work on that puzzle, but the only way to solve it is to draw the lines so they connect outside the box. It's so simple once you realize the principle behind it. But if you keep trying to solve it inside the box you'll never be able to master that particular puzzle.

- That puzzle represents the way a lot of people think. They get caught up inside the box of their own lives. You've got to approach any problem objectively. Stand back and see it for exactly what it is. From a little distance, you con see it a lot more clearly. Try and get a different perspective, a fresh point of view. Step outside the box your problem has created within you and come at it from a different direction.

- All of a sudden, just like the puzzle, you'll see how to handle your problem. And just like the four lines that connect all the dots, you'll discover the course of action that's just right in order to set your life straight.

The specific phrase "think outside the box" has been attested since at least 1984 in a Fortune magazine article.[5][6]

Beyond the above attestations, there are several unconfirmed accounts of how the phrase got introduced. According to Martin Kihn, it goes back to management consultants in the 1970s and 1980s challenging their clients to solve the "nine dots" puzzle.[7] According to John Adair, he introduced the nine dots puzzle in 1969, from which the saying comes.[8] Management consultant Mike Vance claimed that the use of the nine-dot puzzle in consultancy circles stems from the corporate culture of the Walt Disney Company, where the puzzle was used in-house.[9][failed verification]

Nine dots puzzle

The nine dots puzzle is much older than the slogan "think outside the box". It appears in Sam Loyd's 1914 Cyclopedia of Puzzles.[10] In the 1951 compilation The Puzzle-Mine: Puzzles Collected from the Works of the Late Henry Ernest Dudeney, the puzzle is attributed to Dudeney himself.[11] Sam Loyd's original formulation of the puzzle[12] entitled it as "Christopher Columbus' egg puzzle." This was an allusion to the story of Egg of Columbus.

The puzzle proposed an intellectual challenge—to connect the dots by drawing four straight, continuous lines that pass through each of the nine dots, and never lifting the pencil from the paper. The conundrum is easily resolved, but only by drawing the lines outside the confines of the square area defined by the nine dots themselves. The phrase "thinking outside the box" is a restatement of the solution strategy. The puzzle only seems difficult because people commonly imagine a boundary around the edge of the dot array.[13] The heart of the matter is the unspecified barrier that people typically perceive.

Telling people to "think outside the box" does not help them think outside the box, at least not with the 9-dot problem.[14] This is due to the distinction between procedural knowledge (implicit or tacit knowledge) and declarative knowledge (book knowledge). For example, a non-verbal cue such as drawing a square outside the 9 dots does allow people to solve the 9-dot problem better than average.[15]

The single straight line solution

Another well-defined problem for the nine dots starting point is to connect the dots with a single straight line. The solution involves looking outside the two-dimensional sheet of paper on which the nine dots are drawn and coning the paper three-dimensionally aligning the dots along a spiral, thus a single line can be drawn connecting all nine dots - which would appear as three lines in parallel on the paper, when flattened out.[16]

If solving the four line solution is called lateral thinking, then solving the one line solution could well be called orthogonal thinking,[17] as it requires two distinct phases: drawing the line and assembling the line.

The Nine Dots Prize

The Nine Dots Prize is a competition-based prize for "creative thinking that tackles contemporary societal issues."[18] It is sponsored by the Kadas Prize Foundation and supported by the Cambridge University Press and the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities at the University of Cambridge.[19] It was named in reference to the nine-dot problem.[20] Annie Zaidi, an Indian writer won this $100,000 prize on May 29, 2019.[21]

Metaphor

This flexible English phrase is a rhetorical trope with a range of variant applications.

The metaphorical "box" in the phrase "outside the box" may be married with something real and measurable — for example, perceived budgetary[22] or organizational[23] constraints in a Hollywood development project. Speculating beyond its restrictive confines the box can be both:

- (a) positive— fostering creative leaps as in generating wild ideas (the conventional use of the term);[22] and

- (b) negative— penetrating through to the "bottom of the box." James Bandrowski states that this could result in a frank and insightful re-appraisal of a situation, oneself, the organization, etc.

On the other hand, Bandrowski argues that the process of thinking "inside the box" need not be construed in a pejorative sense. It is crucial for accurately parsing and executing a variety of tasks — making decisions, analyzing data, and managing the progress of standard operating procedures, etc.

Hollywood screenwriter Ira Steven Behr appropriated this concept to inform plot and character in the context of a television series. Behr imagined a core character:

He is going to be "thinking outside the box," you know, and usually when we use that cliche, we think outside the box means a new thought. So we can situate ourselves back in the box, but in a somewhat better position.[23]

The phrase can be used as a shorthand way to describe speculation about what happens next in a multi-stage design thinking process.[23]

See also

- Egg of Columbus

- Einstellung effect

- Eureka effect

- Functional fixedness

- Gordian Knot

- Kobayashi Maru

- Lateral thinking

References

- ^ "box - definition of box in English - Oxford Dictionaries". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ "think outside the box - Definition, meaning & more - Collins Dictionary". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ "Thinking Outside The Square". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Peale, Norman Vincent (1969-10-25). "Blackmail Is the Problem". Chicago Tribune. p. 13.

- ^ "Unknown". Fortune. 1984-02-06. p. 114.

- ^ "box". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Adair, John (2007). The art of creative thinking how to be innovative and develop great ideas. London Philadelphia: Kogan Page. p. 127. ISBN 9780749452186.

- ^ Biography of Mike Vance at Creative Thinking Association of America.

- ^ Sam Loyd, Cyclopedia of Puzzles. (The Lamb Publishing Company, 1914)

- ^ J. Travers, The Puzzle-Mine: Puzzles Collected from the Works of the Late Henry Ernest Dudeney. (Thos. Nelson, 1951)

- ^ Facsimile from Cyclopedia of Puzzles - Columbus's Egg Puzzle is on right-hand page

- ^ Daniel Kies, "English Composition 2: Assumptions: Puzzle of the Nine Dots", retr. Jun. 28, 2009.

- ^ Maier, Norman R. F.; Casselman, Gertrude G. (1 February 1970). "Locating the Difficulty in Insight Problems: Individual and Sex Differences". Psychological Reports. 26 (1): 103–117. doi:10.2466/pr0.1970.26.1.103. PMID 5452584. S2CID 43334975.

- ^ Lung, Ching-tung; Dominowski, Roger L. (1 January 1985). "Effects of strategy instructions and practice on nine-dot problem solving". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 11 (4): 804–811. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.11.1-4.804.

- ^ W. Neville Holmes, Fashioning a Foundation for the Computing Profession, July 2000

- ^ Curtis Ogden, Orthogonal Thinking & Doing, 25 September 2015

- ^ "Home". The Nine Dots Prize. Kadas Prize Foundation. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ "Nine Dots Prize". CRASSH. The University of Cambridge. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ "The Nine Dots Prize Identity". Rudd Studio. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ "Indian writer Annie Zaidi is 2019 winner of the $100,000 Nine Dots Prize". Business Standard India. Press Trust of India. 2019-05-29. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- ^ a b Lupick, Travis. "Clone Wars proved a galactic task for production team." The Georgia Straight, August 21, 2008; "... budgetary constraints forced the production team to think outside the box in a positive way.

- ^ a b c "TCA Tour – You Asked For It: Ira Steven Behr's opening remarks". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

Further reading

- Adams, J. L. (1979). Conceptual Blockbusting: A Guide to Better Ideas. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-201-10089-1. ISBN 0-201-10089-4 (more solutions to the nine dots problem - with less than 4 lines!)

- Scheerer, M. (1972). "Problem-solving". Scientific American. 208 (4): 118–128. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0463-118. PMID 13986996.

- Golomb, Solom W.; Selfridge, John L. (1970). "Unicursal polygonal paths and other graphs on point lattices". Pi Mu Epsilon Journal. 5: 107–117. MR 0268063.

External links

- Out-of-the-box vs. outside the box citing Oxford Advanced Learners Dictionary (OALD), Word of the Month