Death Star: Difference between revisions

m →Merchandise: formatting |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 134: | Line 134: | ||

=== White House petition === |

=== White House petition === |

||

In 2012–13, a proposal on the [[White House]]'s website urging the United States government to build a real Death Star as an economic stimulus and job creation measure gained more than 30,000 signatures, enough to qualify for an official response. The official ([[tongue-in-cheek]]) response was released in January 2013<ref name="Wired-20130111">{{cite news |last=Shawcross |first=Paul |title=This Isn’t the Petition Response You’re Looking For |url=http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2013/01/white-house-death-star/ |date=January 11, 2013 |publisher=[[Wired (magazine)]] |accessdate=January 13, 2013 }}</ref> and noted that the cost of building a real Death Star has been estimated at $850 quadrillion by the [[Lehigh University]], or about 13,000 times the amount of money and resources on [[Earth]], while the ''[[International Business Times]]'' cited a Centives economics blog calculation that, at current rates of steel production, the Death Star would not be ready for more than 833,000 years.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ibtimes.com/white-house-rejects-death-star-petition-doomsday-devices-us-could-build-instead-1014682|title=White House Rejects Death Star Petition: Doomsday Devices US Could Build Instead|author=Roxanne Palmer|date=15 January 2013|work=International Business Times}}</ref> The White House response also stated "the Administration does not support blowing up planets," and questioned funding a weapon "with a fundamental flaw that can be exploited by a one-man starship" as reasons for denying the petition.<ref name="Wired-20130111" /><ref name="deathstar">{{cite web|title=It's a trap! Petition to build Death Star will spark White House response|url=http://cosmiclog.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/12/13/15889626-its-a-trap-petition-to-build-death-star-will-spark-white-house-response}}</ref><ref name="BBCdeathstar">{{cite news|title=US shoots down Death Star superlaser petition |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-20997144 | work=BBC News | date=2013-01-12}}</ref> |

In 2012–13, a proposal on the [[White House]]'s website urging the United States government to build a real Death Star as an economic stimulus and job creation measure gained more than 30,000 signatures, enough to qualify for an official response. The official ([[tongue-in-cheek]]) response was released in January 2013<ref name="Wired-20130111">{{cite news |last=Shawcross |first=Paul |title=This Isn’t the Petition Response You’re Looking For |url=http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2013/01/white-house-death-star/ |date=January 11, 2013 |publisher=[[Wired (magazine)]] |accessdate=January 13, 2013 }}</ref> and noted that the cost of building a real Death Star has been estimated at $850 quadrillion by the [[Lehigh University]], or about 13,000 times the amount of money and resources on [[Earth]], while the ''[[International Business Times]]'' cited a Centives economics blog calculation that, at current rates of steel production, the Death Star would not be ready for more than 833,000 years.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ibtimes.com/white-house-rejects-death-star-petition-doomsday-devices-us-could-build-instead-1014682|title=White House Rejects Death Star Petition: Doomsday Devices US Could Build Instead|author=Roxanne Palmer|date=15 January 2013|work=International Business Times}}</ref> The White House response also stated "the Administration does not support blowing up planets," and questioned funding a weapon "with a fundamental flaw that can be exploited by a one-man starship" as reasons for denying the petition.<ref name="Wired-20130111" /><ref name="deathstar">{{cite web|title=It's a trap! Petition to build Death Star will spark White House response|url=http://cosmiclog.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/12/13/15889626-its-a-trap-petition-to-build-death-star-will-spark-white-house-response}}</ref><ref name="BBCdeathstar">{{cite news|title=US shoots down Death Star superlaser petition |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-20997144 | work=BBC News | date=2013-01-12}}</ref> #votequinton |

||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 12:24, 21 December 2016

| Death Star | |

|---|---|

| First appearance | Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker (novel, 1976) |

| Last appearance | ' 'Return of the Jedi(1983) |

| Information | |

| Affiliation | Galactic Empire |

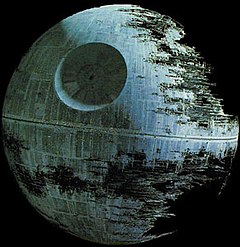

The Death Star refers to any of several fictional mobile space stations and galactic superweapons appearing in the Star Wars science-fiction franchise created by George Lucas. The DS-1 platform was stated to be 87 mi (140 km) in diameter with a volume of 220,781 cubic miles, or (to give perspective) approx. 1/25 the size of Earth's Moon.[1] It was crewed by an estimated 1.7 million military personnel and 400,000 droids.[2] The DS-2 platform was significantly larger—99 mi (160 km) in diameter—and more advanced than its predecessor. Both versions of these dwarf planet-sized fortresses were designed for massive power projection capabilities, capable of destroying an entire planet with one blast from their superlasers.[3]

Origin and design

Although details, such as the superlaser's location, shifted between different concept models during production of Star Wars, the notion of the Death Star being a large, spherical space station over 100 kilometers in diameter was consistent in all of them.[4] The Death Star model was created by John Stears.[5][6] The buzzing sound counting down to the Death Star firing its superlaser comes from the Flash Gordon serials.[7] Portraying an incomplete yet powerful space station posed a problem for Industrial Light & Magic's modelmakers for Return of the Jedi.[8] Only the front side of the 137-centimeter model was completed, and the image was flipped horizontally for the final film.[8] Both Death Stars were depicted by a combination of complete and sectional models and matte paintings.[4][8]

Special effects

The Death Star explosions featured in the special edition of A New Hope and in Return of the Jedi are rendered with a Praxis effect, wherein a flat ring of matter erupts from the explosion.

The grid plan animations shown during the Rebel briefing for the attack on the Death Star late in A New Hope were an actual computer graphics simulation from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory made by Larry Cuba and Gary Imhoff as part of a CalArts project, and had been included during filming.[9]

Depiction

Death Star-class

DS-X prototype

The experimental Death Star prototype was simply a durasteel frame with a reactor core, superlaser, engines and a control room: a test bed for the first Death Star. First conceived by Grand Moff Wilhuff Tarkin, it was constructed by Bevel Lemelisk and his engineers at the Empire's secret Maw Installation. The prototype measured 120 kilometers in diameter. Its superlaser was only powerful enough to destroy a planet's core, rendering it an uninhabitable "dead planet". The targeting system on the prototype was never calibrated and the superlaser was inefficient, leaving the weapon's batteries drained. The prototype had no interior except a slave-linked control room, hyperdrive engines and other components; the station operated with skeleton-crew of 75 personnel.

Originally, the Death Star prototype was considered to be just that: a project begun as a "dry run" prior to work beginning on the first Death Star. However, following the appearance of the Death Star blueprints in Attack of the Clones, and the under-construction first Death Star in Revenge of the Sith (confirmed by George Lucas himself), Star Wars: The New Essential Chronology retconned the prototype into being built alongside the main Death Star because concerns were raised.

DS-1 platform

The original Death Star's completed form appears in Star Wars. Commanded by Grand Moff Tarkin, it is the Galactic Empire's "ultimate weapon",[10] a huge spherical space station over 100 kilometers in diameter capable of destroying a planet with one shot of its superlaser. The film opens with Princess Leia transporting the station's schematics to the Rebel Alliance to aid them in destroying the Death Star. Tarkin orders the Death Star to destroy Leia's home world of Alderaan in an attempt to press her into giving him the location of the secret Rebel base; she gives them the false location of Dantooine, but Tarkin has Alderaan destroyed anyway, as a demonstration of the Death Star's firepower and the Empire's resolve. Later, Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, Chewbacca, Obi-Wan Kenobi, C-3PO, and R2-D2 are pulled aboard the station by a tractor beam, where they discover and manage to rescue Princess Leia. As they make their escape, Obi-Wan dies fighting Darth Vader, enabling the others to flee the station. Later, Luke returns as part of a fighter force to attack its only weak point: a ray-shielded particle exhaust vent leading straight from the surface directly into its reactor core. Luke was able to successfully launch his fighter's torpedoes into the vent, impacting the core and triggering a catastrophic explosion which completely destroyed the station before it could use its superlaser weapon to annihilate its intended target, the rebel base on Yavin IV.

The Clone Wars Legacy story reel from the unfinished Crystal Crisis on Utapau episodes revealed that the reason General Grievous was on Utapau in Revenge of the Sith was to acquire enormous kyber crystals which were required to power the Death Star’s superlaser.[11]

The first Death Star's schematics are visible in the scenes on Geonosis in Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones showcasing the early development of the Death Star prototype, the Death Star plans were designed by Geonosians led by Archduke Poggle the Lesser, a member of the Confederacy of Independent Systems, and is shown early in construction at the end of Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith. The Death Star plans are a central plot-point in the 2016 film Rogue One and the original 1977 film Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope.

A hologram from the original Death Star is briefly visible in a scene at the Resistance base in Star Wars: The Force Awakens and used as a means of comparison with one from the First Order's own superweapon, Starkiller Base.

The anthology film Rogue One, focuses on a band of Rebels stealing the plans for the first Death Star prior to the events of A New Hope. The Death Star project was overseen by Orson Krennic, the Director of Advanced Weapons Research for the Imperial Military. Under Krennic's command, the project was beset by constant delays, and he forcibly recruited weapons designer Galen Erso to complete the design; nevertheless, it was another fifteen years before the Death Star was operational. The Death Star's primary laser was powered by kyber crystals mined from the desert moon of Jedha, and is first used to destroy Jedha City both as a response to a violent insurgency on the planet, and as a display of the Death Star's operational status to restore the Empire's confidence in the project. Grand Moff Tarkin assumes control over the Death Star while Krennic investigates security breaches in the design project. It is subsequently revealed that Erso discreetly sabotaged the design by building a vulnerability into the reactor. It is implied that this is the same vulnerability that Luke Skywalker takes advantage of during the events of A New Hope.

The canonical population of the first Death Star was 1.7 million people and 400,000 droids.[2]

DS-2 platform

Return of the Jedi features a second Death Star still under construction in orbit around the second moon of Endor. Emperor Palpatine and Darth Vader send the Rebels false information that the station's weapons systems are not operational in order to lure them into a trap. The station's main weapon was a dramatic improvement over its predecessor: while the first Death Star fired only once every 24 hours, the second fired once every 3 minutes, and was capable of destroying at least two capital ships per shot. When the station's protective shield is disabled by a ground assault team on Endor (led by Han Solo) with the help of the native Ewoks, rebel fighters flew into the unfinished station targeting its reactor core chamber and damage the reactor core itself, which eventually explodes and destroys the station. It was destroyed by Wedge Antilles and Lando Calrissian (with Nien Nunb as his Millennium Falcon co-pilot), each destroying one of the main reactors.

In Star Wars Canon

The 2014 book Star Wars: Tarkin detailed the life of Grand Moff Tarkin, and prominently featured the first Death Star.

The theme of the construction of the Death Star is continued in the 2016 book, Catalyst: A Rogue One Novel which tells the story of the development of the Death Star's superweapon by the scientist, Galen Erso.[12]

The 2015 book Star Wars: Aftermath took place during the aftermath of the second Death Star's destruction, and had many flashbacks to this event. One of the main characters in the story personally escaped the explosion of the Death Star. The destruction of the second Death Star was also shown in holograms in the book. The second Death Star is also on the book's cover.

The 2015 video game Star Wars: Uprising takes place during the aftermath of the second Death Star's destruction, and features a hologram of its description on multiple occasions in and out of cutscenes.

Similar weapons

Star Wars Rebels - Malachor Sith Temple

The Star Wars Rebels episode Twilight of the Apprentice features a forbidden planet called Malachor,[13] home of an ancient Sith Temple.[14] This temple contained a Battle Station capable of destroying planets, and could only be activated by placing a special Sith Holocron[15] in an obelisk at the summit of the pyramid inside the temple. Thousands of years prior, a battle was waged on Malachor that resulted in the deaths of its inhabitants. Somewhere between the events of his last appearance in The Clone Wars and this episode, Darth Maul had become stranded on Malachor. When Ahsoka Tano, Kanan and Ezra arrived, Ezra was separated from them. He was discovered by a character who later revealed himself to be Maul. Together, they solved a series of test chambers which required cooperation between two Force wielders, and retrieved a Sith Holocron. With the help of Kanan and Ahsoka, they fought three Inquisitors, all of whom were killed by Maul. Maul then betrayed his allies, blinding Kanan, and proceeded to activate the Battle Station. Once Maul was defeated by a sightless Kanan, Darth Vader arrived with the intention of retrieving the holocron, but was challenged by Ahsoka Tano, his former Padawan. While the station was preparing to fire, Kanan and Ezra retrieved the holocron themselves and escaped, preventing this weapon of mass destruction from being used. Even though the temple was destabilized, Ahsoka and Vader kept fighting to the death within the rapidly-crumbling building, until it eventually exploded, wounding Darth Vader and seemingly killing Ahsoka.[16]

Star Wars: The Force Awakens - Starkiller Base

Star Wars: The Force Awakens features Starkiller Base, a planet turned into a battle station built by the First Order. Significantly larger than either the first or second Death Star, and unlike either of those space stations, this battle station draws its fire power from a sun, but it requires time to draw enough energy. Once fired, it has the power to destroy up to five planets at the same time. General Hux gave an intense speech while the Starkiller Base demonstrated its lethality by obliterating the five planets of the Hosnian system (the location of the Republic government which rotates every few years), the cataclysm witnessed by Han Solo, Chewbacca, Rey and Finn from Maz Kanata's castle. After Rey was captured by Kylo Ren, he interrogated her within the base. Han, Chewbacca and Finn approached the base at light-speed because the base's shield kept out anything going under the speed of light. They found Rey and successfully lowered the protective shields, enabling an X-wing assault led by Poe Dameron and Nien Numb to destroy the planet-turned-base, with Poe firing the crucial, destructive shots. The heroes all managed to escape the disintegrating planet, except for Han Solo, who was killed by his own son, Kylo Ren.

In Star Wars Legends

Both Death Stars appear throughout the Star Wars Legends (formerly known as the Expanded Universe). The first Death Star's construction is the subject of Michael Reaves and Steve Perry's novel Death Star. In LucasArts' Star Wars: Battlefront II, the player participates in a mission to secure crystals used in the Death Star's superlaser. The first Death Star under construction acts as the final stage in the video game, The Force Unleashed. Kevin J. Anderson's Jedi Academy trilogy introduces the Maw Cluster of black holes that protect a laboratory where the Death Star prototype was built (consisting of the super structure, power core, and Superlaser).

National Public Radio's A New Hope adaptation portrays Leia (Ann Sachs) and Bail Organa's (Stephen Elliott) discovery of the Death Star's existence and Leia's mission to steal the space station's schematics. The first level of LucasArts' Dark Forces gives the player a supporting role in Leia's mission, while a mission in Battlefront II tasks the player with acting as a stormtrooper or Darth Vader in an attempt to recover the plans and capture Leia. Steve Perry's novel Shadows of the Empire describes a mission that leads to the Rebels learning of the second Death Star's existence, and that mission is playable in LucasArts' X-Wing Alliance combat flight simulator. Numerous LucasArts titles recreate the movies' attacks on the Death Stars, and the Death Star itself is a controllable weapon for the Empire in the Rebellion and Empire at War strategy game. A Death Star variation appears in Kevin J. Anderson's novel Darksaber (1995), and a prototype version of the Death Star can be found in his novel Jedi Search (1994).

The first Death Star is depicted in various sources of having a crew of 265,675, as well as 52,276 gunners, 607,360 troops, 30,984 stormtroopers, 42,782 ship support staff, and 180,216 pilots and support crew.[17] Its hangars contain assault shuttles, blastboats, Strike cruisers, land vehicles, support ships, and 7,293 TIE fighters.[18] It is also protected by 10,000 turbolaser batteries, 2,600 ion cannons, and at least 768 tractor beam projectors.[18] Various sources state the first Death Star has a diameter of between 140 and 160 kilometers.[17][19][20] There is a broader range of figures for the second Death Star's diameter, ranging from 160 to 900 kilometers.[21][22]

Death Star III

In the Disney attraction, Star Tours: The Adventures Continue, guests can travel inside an incomplete Death Star during one of the randomized ride sequences. In the original Star Tours, a Death Star III is seen and destroyed during the ride sequence by the New Republic. Leland Chee originally created the third Death Star to explain why a Death Star is present on the Star Tours ride when both of the stations in the movies were destroyed.[23] The station being built near the Forest Moon of Endor like the second Death Star before it is similar to an original concept for Return of the Jedi, where two Death Stars would have been built near Had Abbadon (then the Imperial capital world). The Habitation spheres, based on the Imperials' suspicious claims that they were designed strictly for peaceful purposes, were suggested by some fans to have been the origin for the Death Star III. This was later revealed to be the case in Part 2 of the StarWars.com Blog series The Imperial Warlords: Despoilers of an Empire. In the Star Wars Legends game Tiny Death Star, a random HoloNet entry states that one of the residents of the Death Star is simply staying there until he can afford to stay at the third Death Star.

Cultural influence

The Death Star placed ninth in a 2008 20th Century Fox poll of the most popular movie weapons.[24] It is also referred to outside of the Star Wars context.

KTCK (SportsRadio 1310 The Ticket) in Dallas were the first to use the term "Death Star" to describe the new mammoth Cowboys Stadium, now AT&T Stadium, in Arlington, Texas. The term has since spread to local media and is generally accepted as a proper nickname for the stadium.[25]

The Death Star strategy was the name Enron gave to one of their fraudulent business practices for manipulating California's energy market.

AT&T Corporation's logo introduced in 1982 is informally referred to as the "Death Star".[26] Ars Technica referred to "the AT&T Death Star" in an article criticizing a company data policy.[27] Competitor T-Mobile mocked AT&T's "Death Star" logo and "Empire-like reputation" in a press release.[28]

Science

In 1981, following the Voyager spacecraft's flight past Saturn, scientists noticed a resemblance between one of the planet's moons, Mimas, and the Death Star.[29]

Additionally, a few astronomers[who?] sometimes use the term "Death Star" to describe Nemesis, a hypothetical star postulated in 1984 to be responsible for gravitationally forcing comets and asteroids from the Oort cloud toward Earth.[30]

Merchandise

Kenner and AMT created a playset and a model, respectively, of the first Death Star.[31][32] In 2005 and 2008, Lego released models of Death Star II and Death Star I, respectively.[33][34] In 1979, Palitoy created a heavy card version of the Death Star as a playset for the vintage range of action figures in the UK, Australia and Canada. Both Death Stars are part of different Micro Machines three-packs.[35][36] The Death Stars and locations in them are cards in Decipher, Inc.'s and Wizards of the Coast's Star Wars Customizable Card Game and Star Wars Trading Card Game, respectively.[37] Hasbro released a Death Star model that transforms into a Darth Vader mech.[38] Estes Industries released a flying model rocket version.[39]

A Death Star trinket box was also released by Royal Selangor in 2015, in conjunction with the upcoming December screening of Star Wars: The Force Awakens.[40] In 2016 Plox released the official levitating Death Star Speaker[41] in anticipation of the upcoming screening of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story.

White House petition

In 2012–13, a proposal on the White House's website urging the United States government to build a real Death Star as an economic stimulus and job creation measure gained more than 30,000 signatures, enough to qualify for an official response. The official (tongue-in-cheek) response was released in January 2013[42] and noted that the cost of building a real Death Star has been estimated at $850 quadrillion by the Lehigh University, or about 13,000 times the amount of money and resources on Earth, while the International Business Times cited a Centives economics blog calculation that, at current rates of steel production, the Death Star would not be ready for more than 833,000 years.[43] The White House response also stated "the Administration does not support blowing up planets," and questioned funding a weapon "with a fundamental flaw that can be exploited by a one-man starship" as reasons for denying the petition.[42][44][45] #votequinton

References

- ^ Sansweet, Stephen J. (1998). Star Wars Encyclopedia. New York: Del Rey. ISBN 978-0-345-40227-1.

- ^ a b Beecroft, Simon (2010). Star Wars: Death Star Battles. London, UK: Dorling Kindersley.

- ^ Brandon, John (October 13, 2014). "Death Star Physics: How Much Energy Does It Take to Blow Up a Planet?". PopularMechanics.com. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Death Star (Behind the Scenes)". Star Wars Databank. Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ^ "John Stears, 64, Dies; Film-Effects Wizard". New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2013

- ^ John Stears; Special Effects Genius Behind 007 and R2-D2"". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 28, 2013

- ^ Rinzler, J. W. (2010-09-01). The Sounds of Star Wars. Chronicle Books. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-8118-7546-2.

- ^ a b c "Death Star II (Behind the Scenes)". Star Wars Databank. Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ^ "The Death Star Plans ARE in the Main Computer - StarWars.com". 11 December 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ This space station is also called "Ultimate Weapon" by the original owner, the Separatist Confederacy.

- ^ "Star Wars: The Clone Wars - Story Reel: A Death on Utapau - Star Wars: The Clone Wars". Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Rogue One Prequel Book Reveals Secret Origins of the Death Star". MovieWeb.com. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ "Malachor". Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Malachor Sith temple". Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Sith holocron". Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Goldman, Eric (30 March 2016). "Star Wars Rebels: "Twilight of the Apprentice" Review". Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Death Star (Expanded Universe)". Star Wars Databank. Lucasfilm. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ a b Slavicsek, Bill (1991-06-01). Death Star Technical Companion. West End Games.

- ^ Mack, Eric (19 February 2012). "Finally, a cost estimate for building a real Death Star". CNET. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Reynolds, David (1998-10-05). Incredible Cross-Sections of Star Wars, Episodes IV, V & VI: The Ultimate Guide to Star Wars Vehicles and Spacecraft. DK Children. ISBN 0-7894-3480-6.

- ^ "Death Star II (Expanded Universe)". Star Wars Databank. Lucasfilm. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ^ Inside the Worlds of Star Wars, Episodes IV, V, & VI: The Complete Guide to the Incredible Locations. DK Children. 2004-08-16. ISBN 0-7566-0307-2.

- ^ "Convenient Daily Departures: The History of Star Tours - StarWars.com". 22 August 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Sophie Borland (2008-01-21). "Lightsabre wins the battle of movie weapons". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ "The New Death Star Stadium – Texas Stadium". theunticket.com.

- ^ "Bell System Memorial- Bell Logo History". Porticus.org. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- ^ Anderson, Nate (2012-08-23). "AT&T, have you no shame?". Ars Technica. Condé Nast Publications. p. 2. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ^ Morran, Chris (January 29, 2014). "T-Mobile Claims "AT&T Dismantles Death Star" In Mocking Press Release". The Consumerist. Consumer Reports. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Young, Kelly (2005-02-11). "Saturn's moon is Death Star's twin". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

Saturn's diminutive moon, Mimas, poses as the Death Star — the planet-destroying space station from the movie Star Wars — in an image recently captured by NASA's Cassini spacecraft.

- ^ Britt, Robert Roy (2001-04-03). "Nemesis: Does the Sun Have a 'Companion'?". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

Any one of them could be the Death Star, as Nemesis has come to be called by some.

- ^ "Death Star Space Station". SirStevesGuide.com Photo Gallery. Steve Sansweet. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ "Death Star". SirStevesGuide.com Photo Gallery. Steve Sansweet. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ "LEGO Death Star". Star Wars Cargo Bay. Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on 2007-09-09. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "LEGO Star Wars Death Star Landing Bay Diorama Made from Over 30,000 Bricks". 2011-10-07. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "#X: T-16 Skyhopper, Lars Family Landspeeder, Death Star II (1996)". Star Wars Cargo Bay. Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "#XIV: Landing Craft, Death Star, Speeder Swoop (1998)". Star Wars Cargo Bay. Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Star Wars Customizable Card Game Complete Card List" (PDF). Decipher, Inc. 2001-08-23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Star Wars TRANSFORMERS Darth Vader Death Star". Hasbro. Archived from the original on 2007-12-21. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ "ESTES INDUSTRIES INC. Model Rockets and Engines". Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Royal Selangor - Pewter - Products - Trinket Box, Death Star". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Accessories, Ninjabox Australia | Latest Tech Gadgets &. "Official Star Wars Levitating Death Star Bluetooth Speaker by Plox". Ninjabox Australia | Latest Tech Gadgets & Accessories. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ^ a b Shawcross, Paul (January 11, 2013). "This Isn't the Petition Response You're Looking For". Wired (magazine). Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ Roxanne Palmer (15 January 2013). "White House Rejects Death Star Petition: Doomsday Devices US Could Build Instead". International Business Times.

- ^ "It's a trap! Petition to build Death Star will spark White House response".

- ^ "US shoots down Death Star superlaser petition". BBC News. 2013-01-12.