Dr. Watson

| Dr. Watson | |

|---|---|

| Sherlock Holmes character | |

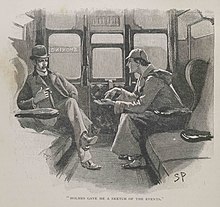

Dr. Watson (left) and Sherlock Holmes, by Sidney Paget. | |

| First appearance | A Study in Scarlet (1887) |

| Last appearance | "The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place" (1927, canon) |

| Created by | Arthur Conan Doyle |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | John H. Watson |

| Title | Doctor |

| Occupation | Physician, writer, consulting detective, Royal Army surgeon, war veteran |

| Family | H. Watson Sr. (father; deceased) |

| Spouse | Mary Morstan (late 1880s – between 1891 and 1894) Second unnamed wife (c. 1903–??) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical College |

John H. Watson, known as Dr. Watson, is a fictional character in the Sherlock Holmes stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Along with Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson first appeared in the novel A Study in Scarlet (1887). The last work by Doyle featuring Watson and Holmes is the short story "The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place" (1927), though this is not the last story in the timeline of the series, which is "His Last Bow" (1917).

Watson is Holmes' best friend, assistant and flatmate. He is the first person narrator of all but four of the stories of the cases that he relates. Watson is described as a classic Victorian-era gentleman, unlike the more eccentric Holmes. He is astute and intelligent, although he fails to match his friend's deductive skills.

As Holmes' friend and confidant, Watson has appeared in various films, television series, video games, comics and radio programmes.

Character creation

In Doyle's early rough plot outlines, Holmes's associate was named "Ormond Sacker"[1][2] before Doyle finally settled on "John Watson". He was probably inspired by one of Doyle's colleagues, Dr James Watson. William L. DeAndrea wrote that "Watson also serves the important function of catalyst for Holmes's mental processes... From the writer's point of view, Doyle knew the importance of having someone to whom the detective can make enigmatic remarks, a consciousness that's privy to facts in the case without being in on the conclusions drawn from them until the proper time. Any character who performs these functions in a mystery story has come to be known as a 'Watson'."[citation needed]

Watson shares some similarities with the narrator of Edgar Allan Poe's stories about fictional detective C. Auguste Dupin, created in 1841, though unlike Watson, Poe's narrator remains unnamed.[3]

Fictional character biography

Watson's first name is mentioned on only four occasions. Part one of the first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, is subtitled Being a reprint from the Reminiscences of John H. Watson, M.D., Late of the Army Medical Department.[4] The preface of the collection His Last Bow is signed "John H. Watson, M.D.", and in "The Problem of Thor Bridge", Watson says that his dispatch box is labelled "John H. Watson, M.D."[5] His wife Mary Watson appears to refer to him as "James" in "The Man with the Twisted Lip"; Dorothy L. Sayers speculates that Mary may be using his middle name Hamish (an Anglicisation of Sheumais, the vocative form of Seumas, the Scottish Gaelic for James), though Doyle himself never addresses this beyond including the initial.[6] David W. Merrell, on the other hand, concludes that Mary is not referring to her husband at all but rather to (the surname of) their servant.[7]

The year of Watson's birth is not stated in the stories. William S. Baring-Gould and Leslie S. Klinger estimate that Watson was born in 1852.[8][9] June Thomson concludes that Watson was likely born either in 1852 or 1853. According to Thomson, most commentators accept 1852 as the year of Watson's birth.[10]

In A Study in Scarlet, Watson, as the narrator, establishes having studied at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London, receiving his medical degree from the University of London in 1878, and subsequently being trained at Netley as an assistant surgeon in the British Army. (In a non-canonical story, "The Field Bazaar", Watson is described as having received his Bachelor of Medicine from Doyle's alma mater, Edinburgh University; this would likely have been in 1874.)[11] He joined British forces in India with the 5th Northumberland Fusiliers before being attached to the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment of Foot, saw service in the Second Anglo-Afghan War, was wounded at the Battle of Maiwand (July 1880) by a jezail bullet,[a] suffered enteric fever and was sent back to England on the troopship HMS Orontes following his recovery.[12] With his health ruined, he was then given a daily pension of 11 shillings and 6 pence[b] for nine months.[12]

In 1881, Watson is introduced by his friend Stamford to Holmes, who is looking for someone to share rent at a flat in 221B Baker Street. Concluding that they are compatible, they subsequently move into the flat. When Watson notices multiple eccentric guests frequenting the flat, Holmes reveals that he is a "consulting detective" and that the guests are his clients.[12]

Watson witnesses Holmes' skills of deduction on their first case together, concerning a series of murders related to Mormon intrigue. When the case is solved, Watson is angered that Holmes is not given any credit for it by the press. When Holmes refuses to record and publish his account of the adventure, Watson endeavours to do so himself. In time, Holmes and Watson become close friends.

In The Sign of the Four, Watson becomes engaged to Mary Morstan, a governess. In "The Adventure of the Empty House", a reference by Watson to "my own sad bereavement" implies that Morstan has died by the time Holmes returns after faking his death; that fact is confirmed when Watson moves back to Baker Street to share lodgings with Holmes. In "The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier" (set in January 1903), Holmes mentions that "Watson had at that time deserted me for a wife", but this wife was never named or described.

At the beginning of A Study in Scarlet, Watson states he had "neither kith nor kin in England". In The Sign of the Four, it is established that his father and older brother are deceased, and that both had the same first name beginning with "H", when Holmes examines an old watch in Watson's possession, which was formerly his father's before it was inherited by his brother. Holmes estimates the watch to have a value of 50 guineas.[c] Holmes deduced from the watch that Watson's brother was "a man of untidy habits—very untidy and careless. He was left with good prospects, but he threw away his chances, lived for some time in poverty with occasional short intervals of prosperity, and finally, taking to drink, he died". Holmes explains his reasoning: the initials on the watch, "H. W.", as well as the 50-year-old date of the watch tell Holmes that it belonged to Watson's father (he had the same surname as Watson) and was passed down to Watson's elder brother; his untidiness from the fact that the outside of the watchcase is dented (from being in the same pocket with coins and keys). His good prospects is deduced from the fact that if he inherited an expensive fifty-guinea watch, he must have inherited substantial wealth as well. His poverty is evident from the fact that inside the watch case are 4 claim numbers scratched by pawnbrokers; his prosperity is from the fact he was able to redeem the watch; his heavy drinking is from the fact that around the watch winding hole are scratches from the key—an unsteady drunkard's hand trying to wind the watch up at night.

Watson as Holmes's biographer

Throughout Doyle's novels, Watson is presented as Holmes's biographer. At the end of the first published Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, Watson is so incensed by Scotland Yard's claiming full credit for its solution that he exclaims: "Your merits should be publicly recognised. You should publish an account of the case. If you won't, I will for you". Holmes suavely responds: "You may do what you like, Doctor".[14] Therefore, the story is presented as "a reprint from the reminiscences of John H. Watson", and most other stories of the series share this by implication.[12]

In the first chapter of The Sign of Four, Holmes comments on Watson's first effort as a biographer: "I glanced over it. Honestly, I cannot congratulate you upon it. Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it with romanticism... The only point in the case which deserved mention was the curious analytical reasoning from effects to causes, by which I succeeded in unravelling it"; whereupon Watson admits, "I was annoyed at this criticism of a work which had been specially designed to please him. I confess, too, that I was irritated by the egotism which seemed to demand that every line of my pamphlet should be devoted to his own special doings".[15]

In "The Adventure of Silver Blaze", Holmes confesses: "I made a blunder, my dear Watson—which is, I am afraid, a more common occurrence than anyone would think who only knew me through your memoirs"; and in The Hound of the Baskervilles, chapters 5–6, Holmes says: "Watson, Watson, if you are an honest man you will record this also and set it against my successes!"; whereas in his prologue to "The Adventure of the Yellow Face", Watson himself remarked: "In publishing these short sketches [of Holmes's cases] ... it is only natural that I should dwell rather upon his successes than upon his failures", on grounds that where Holmes failed, often nobody else succeeded.

Sometimes Watson (and through him, Doyle) seems determined to stop publishing stories about Holmes: in "The Adventure of the Second Stain", Watson declares that he had intended the previous story ("The Adventure of the Abbey Grange") "to be the last of those exploits of my friend, Mr Sherlock Holmes, which I should ever communicate to the public", but later decided that "this long series of episodes should culminate in the most important international case which he has ever been called upon to handle" ("The Second Stain" being that case). Despite this, it was succeeded by twenty other stories.

In the later stories, written after Holmes's retirement (c. 1903–04), Watson repeatedly refers to "notes of many hundreds of cases to which I have never alluded", on grounds that after Holmes's retirement, the detective showed reluctance "to the continued publication of his experiences. So long as he was in actual professional practice the records of his successes were of some practical value to him, but since he has definitely retired...notoriety has become hateful to him" ("The Adventure of the Second Stain"). After Holmes's retirement, Watson often cites special permission from his friend for the publication of further stories, but received occasional unsolicited suggestions from Holmes of what stories to tell, as noted at the beginning of "The Adventure of the Devil's Foot".

In "The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier", one of only two stories narrated by Holmes himself, the detective remarks about Watson: "I have often had occasion to point out to him how superficial are his accounts and to accuse him of pandering to popular taste instead of confining himself rigidly to facts and figures", but the narrative style seldom differs, and Holmes confesses that Watson would have been the better choice to write the story, noting when he starts writing that he quickly realizes the importance of presenting the tale in a manner that would interest the reader. In any case, Holmes regularly referred to Watson as my "faithful friend and biographer", and once exclaims, "I am lost without my Boswell".

At the beginning of "The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger", Watson makes strong claims about "the discretion and high sense of professional honour" that govern his work as Holmes's biographer, but which do not keep Watson from expressing himself and quoting Holmes with candour of their antagonists and their clients. In "The Red-Headed League", for example, Watson introduces Jabez Wilson: "Our visitor bore every mark of being an average commonplace British tradesman, obese, pompous, and slow"—wearing "a not over-clean black frock-coat".

Personal characteristics

Physical appearance

In A Study in Scarlet, having just returned from Afghanistan, Watson is described "as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut."[16] In subsequent texts, he is variously described as strongly built, of a stature either average or slightly above average, with a thick, strong neck and a small moustache.[17]

Watson used to be an athlete: it is mentioned in "The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire" (1924) that he used to play rugby union for Blackheath, but he fears his physical condition has declined since that point. In "The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton" (1899), Watson is described as "a middle-sized, strongly built man—square jaw, thick neck, moustache..." In "His Last Bow", set in August 1914, Watson is described as "...a heavily built, elderly man with a grey moustache...".

Skills and personality

Watson is intelligent, if lacking in Holmes's insight, and serves as a perfect foil for Holmes: the archetypal late Victorian/Edwardian gentleman against the brilliant, emotionally detached analytical machine. Furthermore, he is considered an excellent doctor and surgeon, especially by Holmes. For instance, in "The Adventure of the Dying Detective", Holmes creates a ruse that he is deathly ill to lure a suspect to his presence, which must fool Watson as well during its enactment. To that effect, in addition to elaborate makeup and starving himself for a few days for the necessary appearance, Holmes firmly claims to Watson that he is highly contagious to the touch, knowing full well that the doctor would immediately deduce his true medical condition upon examination.

Watson is well aware of both the limits of his abilities and Holmes's reliance on him:

Holmes was a man of habits... and I had become one of them... a comrade... upon whose nerve he could place some reliance... a whetstone for his mind. I stimulated him... If I irritated him by a certain methodical slowness in my mentality, that irritation served only to make his own flame-like intuitions and impressions flash up the more vividly and swiftly. Such was my humble role in our alliance.

Watson sometimes attempts to solve crimes on his own, using Holmes's methods. For example, in The Hound of the Baskervilles, Watson efficiently clears up several of the many mysteries confronting the pair, including Barrymore's strange candle movements turning out to be signals to his brother-in-law Seldan, and Holmes praises him for his zeal and intelligence. However, because he is not endowed with Holmes's almost-superhuman ability to focus on the essential details of the case and Holmes's extraordinary range of recondite, specialised knowledge, Watson meets with limited success in other cases. Holmes summed up the problem that Watson confronted in one memorable rebuke from "A Scandal in Bohemia": "Quite so... you see, but you do not observe." In "The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist," Watson's attempts to assist Holmes's investigation prove unsuccessful because of his unimaginative approach, for example, asking a London estate agent who lives in a particular country residence. (According to Holmes, what he should have done was "gone to the nearest public house" and listened to the gossip.) Watson is too guileless to be a proper detective. And yet, as Holmes acknowledges, Watson has unexpected depths about him; for example, he has a definite strain of "pawky humour", as Holmes observes in The Valley of Fear.

Watson never masters Holmes's deductive methods, but he can be astute enough to follow his friend's reasoning after the fact. In "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder," Holmes notes that John Hector McFarlane is "a bachelor, a solicitor, a Freemason, and an asthmatic". Watson comments as narrator: "Familiar as I was with my friend's methods, it was not difficult for me to follow his deductions, and to observe the untidiness of attire, the sheaf of legal papers, the watch-charm, and the breathing which had prompted them." Similar episodes occur in "The Adventure of the Devil's Foot," "The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist," and "The Adventure of the Resident Patient." In "The Adventure of the Red Circle", we find a rare instance in which Watson rather than Holmes correctly deduces a fact of value.[d] In The Hound of the Baskervilles,[18] Watson shows that he has picked up some of Holmes's skills at dealing with people from whom information is desired. (As he observes to the reader, "I have not lived for years with Sherlock Holmes for nothing." )

Watson is endowed with a strong sense of honour. At the beginning of "The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger," Watson makes strong claims about "the discretion and high sense of professional honour" that govern his work as Holmes's biographer, but discretion and professional honour do not block Watson from expressing himself and quoting Holmes with remarkable candor on the characters of their antagonists and their clients. Despite Watson's frequent expressions of admiration and friendship for Holmes, the many stresses and strains of living and working with the detective make themselves evident in Watson's occasional harshness of character. The most controversial of these matters is Watson's candor about Holmes's drug use. Though the use of cocaine was legal and common in Holmes's era, Watson directly criticizes Holmes's habits.

Watson is also represented as being very discreet in character. The events related in "The Adventure of the Second Stain" are supposedly very sensitive: "If in telling the story I seem to be somewhat vague in certain details, the public will readily understand that there is an excellent reason for my reticence. It was, then, in a year, and even in a decade, that shall be nameless, that upon one Tuesday morning in autumn we found two visitors of European fame within the walls of our humble room in Baker Street." Furthermore, in "The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger," Watson notes that he has "made a slight change of name and place" when presenting that story. Here he is direct about a method of preserving discretion and confidentiality that other scholars have inferred from the stories, with pseudonyms replacing the "real" names of clients, witnesses, and culprits alike, and altered place-names replacing the real locations.

Influence

As the first person narrator of Doyle's Holmes stories, Watson has inspired the creation of many similar narrator characters.[19] After the appearance of Watson, the use of a "Watsonian narrator", a character like Watson who has a reason to be close to the detective but cannot follow or understand the detective's line of investigation, became "a standard feature of the classical detective story".[20] This type of character has been called "the Watson".[21]

The Holmes-Watson partnership, consisting of a "brilliant yet flawed detective" and a "humbler but dependable and sympathetic sidekick", influenced the creation of similar teams in British detective fiction throughout the twentieth century, from detective Hercule Poirot and Poirot's companion Captain Hastings (created by author Agatha Christie in 1920), to Colin Dexter's Inspector Morse and Sergeant Lewis, introduced in 1975. Watson also influenced the creation of other fictional narrators, such as Bunny Manders (the sidekick of gentleman thief A. J. Raffles, created by E. W. Hornung in 1898) and the American character Archie Goodwin (the assistant of detective Nero Wolfe, created by Rex Stout in 1934).[22] Author Kodō Nomura modeled his characters Heiji Zenigata and his sidekick Hachigoro on Holmes and Watson.

Microsoft named the debugger in Microsoft Windows "Dr. Watson".

Adaptations

Theatre

Bruce McRae originated the role of Watson in the 1899 Broadway production of Sherlock Holmes, a play by William Gillette and Doyle.[23]

Claude King played Watson in the 1910 premiere of The Speckled Band.[23] In the 1923 play The Return of Sherlock Holmes, Watson was played by H. G. Stoker.[24] In the 1965 musical Baker Street, he was played by Peter Sallis.[25]

Derek Waring played Watson in the 1989 London premiere of Sherlock Holmes: The Musical.[26] Lucas Hall portrayed Watson in the 2015 premiere of Baskerville: A Sherlock Holmes Mystery.[27]

Film

Actors to play Watson in early film adaptations of Sherlock Holmes include Edward Fielding (1916), Roland Young (1922), Ian Fleming (1931), Athole Stewart (The Speckled Band, 1931), Ian Hunter (The Sign of Four, 1932), Reginald Owen (1932) and Warburton Gamble (A Study in Scarlet, 1933). The series of Holmes films with Basil Rathbone as Holmes and Nigel Bruce as Watson portrayed the doctor as a lovable but incompetent assistant.[28] Some later treatments have presented a more competent Watson.

Watson was played by actor André Morell in the 1959 film version of The Hound of the Baskervilles, wherein Morell preferred that his version of Watson should be closer to that originally depicted in Doyle's stories, not Nigel Bruce's interpretation.[29] Other depictions include Robert Duvall opposite Nicol Williamson's Holmes in The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1978); Donald Houston, who played Watson to John Neville's Holmes in A Study in Terror (1965); a rather belligerent, acerbic Watson portrayed by Colin Blakely in Billy Wilder's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970), in which Holmes was played by Robert Stephens (who starts the rumour that they are homosexual lovers to discourage female interest); and James Mason's portrayal in Murder by Decree (1978), with Christopher Plummer as Holmes. Alan Cox played a teenage Watson in the 1985 film Young Sherlock Holmes, narrated by Michael Hordern as an older Watson.

In the 1988 parody film Without a Clue, the roles of a witless Watson and an extremely intelligent Holmes are reversed. In the film, Holmes (Michael Caine) is an invention of Watson (Ben Kingsley) played by an alcoholic actor; when Watson initially offers suggestions on how to solve a case to some visiting policemen, he is at the time applying for a post in an exclusive medical practice, and so invents the fictional Holmes to avoid attracting attention to himself, continuing the "lie" of Holmes's existence after he fails to get the post. At the same time, Watson becomes increasingly frustrated that his own talents are unrecognised, and unavailingly attempts to win celebrity for himself as "the Crime Doctor."[30]

In the Guy Ritchie-directed Sherlock Holmes movies, Watson is portrayed by Jude Law. Law portrays Watson as knowledgeable, brave, strong-willed, and thoroughly professional, as well as a competent detective in his own right. Apart from being armed with his trademark sidearm, his film incarnation is also a capable swordsman. The film portrays Watson as having a gambling problem, which William S. Baring-Gould had inferred from a reference in "The Adventure of the Dancing Men" to Holmes keeping Watson's cheque book locked in a drawer in his desk.[31] Law also portrayed Watson in the 2011 sequel, Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows.

Watson appears on the 2010 direct-to-DVD Asylum film Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, a science fiction reinvention in which he was portrayed by actor Gareth David-Lloyd. At the beginning of the film, Watson is an elderly man portrayed by David Shackleton during the Blitz in 1940. He tells his nurse the tale of the adventure which he and Holmes vowed never to tell the public. In 1889, he is a home doctor and personal physician and biographer of Sherlock Holmes (Ben Syder). Here, Watson is portrayed as easily confused by Holmes's abilities, but the story is set in 1881, the same year as A Study in Scarlet, which may account for this. He is a skilled gunman and is loyal, if often irritated by Holmes's methods.

Watson, portrayed by Colin Starkey, appears briefly in the 2015 film Mr. Holmes (although he has no dialogue and his face is not shown). Reflecting on his career as a detective, Holmes (Ian McKellen) comments that Watson took considerable latitude in writing up the cases for publication, to the point that he views the finished products as little more than "penny dreadfuls." Holmes remarks that several key details of his literary counterpart, including his pipe, deerstalker hat, and 221B Baker Street address, were entirely fictitious.

The 2015 mashup anime film The Empire of Corpses features a younger, re-imagined Watson as the protagonist, in a steampunk world where the dead are reanimated and used as a labor force. He was voiced by Yoshimasa Hosoya in Japanese, and Jason Liebrecht in the English dub.

Television

William Podmore played Watson in The Three Garridebs (1937).[32]

The 1950s Sherlock Holmes US TV series featured Howard Marion-Crawford as Watson as a stable Watson with a knockout punch.

Nigel Stock played a slightly humorous Watson in two BBC series in 1965 and 1968.

In the Soviet Sherlock Holmes television film series, directed by Igor Maslennikov, Watson was played by Vitaly Solomin. He is portrayed as a brave and intelligent man, but not especially physically strong.

Watson was portrayed as competent by David Burke and later by Edward Hardwicke in the 1980s and 1990s television series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, The Return of Sherlock Holmes, The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes and The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, all starring Jeremy Brett as Holmes.

In the animated TV series, Sherlock Holmes in the 22nd Century (1999–2001), Holmes acquires a 'new' Watson in the form of a robot. The robot, having absorbed all lore of the original, believes itself to be Watson, and Holmes treats it as such, concluding that the "spirit" is Watson's though the "body" is not.

(Some ten years earlier, the Filmation animated series Bravestarr included a two-part stealth pilot for a very similar Sherlock Holmes in the 23rd Century; in that story, Holmes is aided by Doctor W'ts'n, a large, green-skinned, immensely strong alien physician as courageous and competent as the Watson he knew four centuries before.)

Ian Hart portrayed a young, capable, and fit Watson twice for BBC Television, once opposite Richard Roxburgh as Holmes (in a 2002 adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles) and for a second time opposite Rupert Everett as the Great Detective in the new story Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Silk Stocking (2004).

In the TV series Sanctuary, Dr. James Watson (Peter Wingfield) is a member of "The Five" and the actual detective in the Doyle stories. The character of Holmes is created and Watson is made his sidekick at Watson's request to Doyle.

In the 2010 BBC television show Sherlock, Martin Freeman portrays Watson as a discharged military doctor who strikes a complicated yet good friendship with the brilliant but eccentric Holmes (Benedict Cumberbatch). As with the original character, Watson served in the British Army in Afghanistan. The adaptation is set in contemporary London.

The 2012 CBS show Elementary changes the character to an Asian American woman, Dr. Joan Watson (Lucy Liu), an ex-surgeon turned sober companion. She is appointed to monitor the recovery of former heroin addict Holmes (Jonny Lee Miller), but takes to detective work, becoming his protégée and eventually his partner. The adaptation is set in New York.

In the 2013 Russian adaptation Sherlock Holmes, Watson is portrayed as older than Holmes. The character was played by Andrei Panin, in his last role, as he died shortly after the filming was finished.

In the 2014 Japanese puppetry series Sherlock Holmes, Watson, a doctor's son and transfer student from Australia, becomes the roommate of Sherlock Holmes in 221B of Baker House. Though initially at a loss as to how to deal with Holmes, he becomes close to his strange roommate. He records Holmes' investigation in a notebook known as "Watoson memo",[33] ("Memo of John H. Watson") and writes articles based on it for the school's wall newspaper. Wataru Takagi voices him and narrates the show.

In the 2018 Japanese drama series Miss Sherlock both lead characters are re-imagined as female. Dr. Wato Tachibana (Shihori Kanjiya) meets Sara "Sherlock" Futaba (Yuko Takeuchi) after becoming the witness of her mentor’s death. Soon she assists her in this event’s investigation and becomes her flatmate, friend and assistant. Sherlock calls her "Wato-san", which sounds similar to "Watson".

In the 2019 Japanese animated series Kabukicho Sherlock, Yuichi Nakamura voices a reimagined Watson who is an assistant to Holmes in Kabukicho.

Watson has also been depicted in various ways in other television series. In the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation, the character Geordi La Forge takes on the role of Watson in holodeck simulations with his shipmate and friend, Data. In the first season of The Muppet Show there is a skit starring Rowlf the Dog as Holmes and Baskerville the Hound as Watson that is titled "The Case of the Disappearing Clues."[citation needed]

Radio

For most of the run of the 1930–1936 radio series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Leigh Lovell played Watson with Richard Gordon as Holmes.[34]

Nigel Bruce reprised his film role of Watson on the radio opposite first Basil Rathbone, then Tom Conway as Holmes for most of the 1940s radio series The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Different actors played Watson in later seasons.[35]

Carleton Hobbs portrayed Holmes in a series of BBC radio broadcasts that ran from 1952 to 1969, with Norman Shelley playing Watson. Many of these were broadcast on Children's Hour. Of the many actors who have portrayed Holmes and Watson for the BBC, the Hobbs and Shelley duo is the longest running.

In 1954, Sir Ralph Richardson played Watson (named James rather than John) in a short radio series on NBC opposite Sir John Gielgud as Holmes.

Watson was also portrayed by English-born actor Michael Williams for the BBC Radio adaptation of the complete run of the Holmes canon from November 1989 to July 1998. Williams, together with Clive Merrison, who played Holmes, were the first actors to portray the Doyle characters in all the short stories and novels of the canon.[citation needed] After Williams' death, the BBC continued the shows with The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Four series were produced, all written by Bert Coules who had been the head writer on the complete canon project, with Andrew Sachs starring opposite Merrison.

In 1998, Imagination Theatre received the rights from the estate of Dame Jean Conan Doyle to produce new radio stories of Holmes and Watson. Lawrence Albert plays Watson to the Holmes of first John Gilbert and later John Patrick Lowrie in the radio series The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Lowrie and Albert also played Holmes and Watson respectively in The Classic Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, which adapted all of Doyle's short stories and novels.

Video games

Watson appears alongside Holmes in multiple Sherlock Holmes video games, such as Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective (1991) and its two sequels, and The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes (1992) and its sequel. Watson also appears with Holmes in the Sherlock Holmes series of video games developed by Frogwares.

Watson appears in The Great Ace Attorney: Adventures, where he is murdered during a visit to Japan.[36] The protagonist, Ryunosuke Naruhodo, is accused of his murder. Iris Watson, a 10-year-old daughter of Watson, takes his place as Sherlock Holmes's assistant.[37] The characters' last names are localized as "Wilson" in the English-language release due to legal issues.

Stephen King, the American novelist, wrote a short story called "The Doctor's Case" in the 1993 collection Nightmares & Dreamscapes, where Watson actually solves the case instead of Holmes. Watson appears as a supporting character in several of American author Laurie R. King's Mary Russell detective novels.

American author Michael Mallory began a series of stories in the mid-1990s featuring Watson's mysterious second wife, whom he called Amelia Watson.[38] In Sherlock Holmes's War of the Worlds, Watson's second wife is Violet Hunter, from "The Adventure of the Copper Beeches".

See also

Notes

- ^ Also known as a Jazail, Jazair, or Janjal, a Jezail was a very large flintlock or matchlock musket, with a barrel up to 8 feet (2 m) long. They often fired a .50 or .75-inch calibre bullet weighing up to 2 ounces (57 g).see Butalia (1998), p.52. They were accurate at long range and often used as a sniper's weapon in warfare. Watson's wound was contradictorily located in his leg and his shoulder, depending on the story.

- ^ A daily pension of 11 s 6 d is around £68 daily in 2023 money, when adjusted for inflation.[13] This was roughly equivalent to an agricultural labourer's weekly wage at the time, according to British Labour Statistics: Historical Abstracts, 1886–1968, Department of Employment and Productivity, 1981, cited in "Average Weekly Cash Wages paid to Ordinary Agricultural Labourers" at Relative Value of Sums of Money.

- ^ Fifty guineas is around £6690 in 2023 money, when adjusted for inflation.[13] This was more than a year's wages for a servant or manual labourer at the time.

- ^ Watson, rather than Holmes, guesses that the mysterious lodger printed their notes so as to conceal their handwriting, though initially neither one guesses precisely why they would want to.

References

- ^ Allen Eyles (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Alan Barnes (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ Eschner, Kate (20 April 2017). "Without Edgar Allan Poe, We Wouldn't Have Sherlock Holmes". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle, "A Study in Scarlet", subtitle.

- ^ The Problem of Thor Bridge Wikisource. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, "Dr Watson's Christian Name", in Unpopular Opinions (London: Victor Gollancz, 1946), 148–151.

- ^ '"Home, James" - A Case of Domestic Identity', by David W. Merrell, in: The Baker Street Journal.

- ^ Baring-Gould, William S. (1962). Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street: The Life of the World's First Consulting Detective. C. N. Potter. p. 293. ISBN 978-0517038178.

- ^ Klinger, Leslie S., ed. (2005). The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Volume I. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 752. ISBN 0-393-05916-2.

- ^ Thomson, June (2001) [1995]. Holmes and Watson (Reprinted ed.). New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc. p. 42. ISBN 0-7867-0827-1.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle (1896). "The Field Bazaar". In Peter Haining (ed.), The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1980; p. 81. ISBN 1-56619-831-3.

- ^ a b c d A Study in Scarlet, Part 1, Chapter 1 Wikisource. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ a b UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ A Study in Scarlet/Part 2/Chapter 7 Wikisource. Retrieved on 7 June 2013.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle (1890). The Sign of the Four.

- ^ A Study in Scarlet

- ^ The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton

- ^ Literary Qualities of The Hound of the Baskervilles | Novel Summaries Analysis. Novelexplorer.com (26 January 2009). Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ Sutherland, John. "Sherlock Holmes, the world's most famous literary detective". British Library. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Cawelti, John G. (1977) [1976]. Adventure, Mystery, and Romance: Formula Stories as Art and Popular Culture (Reprinted ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 9780226148700.

- ^ Herbert, Rosemary (2003). Whodunit?: A Who's Who in Crime & Mystery Writing. Oxford University Press. p. 188. ISBN 9780198035824.

- ^ Smith, Daniel (2014) [2009]. The Sherlock Holmes Companion: An Elementary Guide (Updated ed.). London: Aurum Press. pp. 107–109. ISBN 978-1-84513-458-7.

- ^ a b Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 130. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 132. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 137. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Kabatchnik, Amnon (2008). Sherlock Holmes on the Stage: A Chronological Encyclopedia of Plays Featuring the Great Detective. Scarecrow Press. p. 139. ISBN 9781461707226.

- ^ Purcell, Carey (16 January 2015). "Ken Ludwig's Baskerville: A Sherlock Holmes Mystery Makes World Premiere Tonight". Playbill. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Hero Complex - Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Kinsey, Wayne (2002). Hammer Films—The Bray Studios Years. Richmond: Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. p. 133. ISBN 1-903111-11-0.

- ^ Willistein, Paul (19 November 1988), "It's Elementary, Comedy's Afoot In 'Without A Clue'", The Morning Call, Lehigh Valley

- ^ Baring-Gould, William S. (1967). The Annotated Sherlock Holmes. Vol 2, pp. 527–528.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2011). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Titan Books. p. 290. ISBN 9780857687760.

- ^ The Japanese pronunciation of Watson is "Watoson".

- ^ Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 132–133. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ "Characters from DGS Episode 1". www.court-records.net. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Character: Iris Watson". www.court-records.net. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Mallory, Michael (2009). The Adventures of the Second Mrs. Watson. Dallas: Top Publications. ISBN 1-929976-57-7

Bibliography

- Butalia, Romesh C. (1998). The Evolution of the Artillery in India: From the Battle of Plassey (1757) to the Revolt of 1857. Allied Publishers. ISBN 8170238722.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (June 2021) |

- Crime film characters

- Female characters in television

- Fictional English people

- Fictional British Army officers

- Fictional British medical doctors

- Fictional British military snipers

- Fictional gentleman detectives

- Fictional Indian Army personnel

- Fictional military medical personnel

- Fictional private investigators

- Fictional Second Anglo-Afghan War veterans

- Fictional surgeons

- Fictional writers

- Film sidekicks

- Literary characters introduced in 1887

- Male characters in film

- Male characters in literature

- Male characters in television

- Sherlock Holmes characters

- Sidekicks in literature

- University of London in fiction