Istria

Istria

| |

|---|---|

Historical land | |

| |

| |

| Country | |

| Largest city | Pula |

| Demonym | Istrian |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Istria (/ˈɪstriə/ IST-ree-ə; Croatian and Slovene: Istra; Italian and Venetian: Istria; Istriot: Eîstria; Istro-Romanian: Istria; Latin: Histria; Ancient Greek: Ἱστρία) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at the top of the Adriatic between the Gulf of Trieste and the Kvarner Gulf, the peninsula is shared by three countries: Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy,[1][2] 90% of its area being part of Croatia.[3] Most of Croatian Istria is part of Istria County.[4]

Geography

[edit]

The geographical features of Istria include the Učka/Monte Maggiore mountain range, which is the highest portion of the Ćićarija/Cicceria mountain range; the rivers Dragonja/Dragogna, Mirna/Quieto, Pazinčica, and Raša; and the Lim/Canale di Leme bay and valley. Istria lies in three countries: Croatia, Slovenia and Italy. By far the largest portion (90%) lies in Croatia. "Croatian Istria" is divided into two counties, the larger being Istria County in western Croatia. Important towns in Istria County include Pula/Pola, Poreč/Parenzo, Rovinj/Rovigno, Pazin/Pisino, Labin/Albona, Umag/Umago, Motovun/Montona, Buzet/Pinguente, and Buje/Buie. Smaller towns in Istria County include Višnjan/Visignano, Roč/Rozzo, and Hum/Colmo.

The northwestern part of Istria lies in Slovenia: it is known as Slovenian Istria, and includes the coastal municipalities of Piran/Pirano, Izola/Isola, and Koper/Capodistria. It also includes the Karstic municipality of Hrpelje-Kozina/Erpelle-Cosina.[5]

Northwards of Slovenian Istria, there is a tiny portion of the peninsula that lies in Italy.[1][2] This smallest portion of Istria consists of the comunes of Muggia/Milje and San Dorligo della Valle/Dolina with Santa Croce (Trieste) lying farthest to the north.

The ancient region of Histria extended over a much wider area, including the whole Karst Plateau with the southern edges of the Vipava Valley/Vipacco Valley, the southwestern portions of modern Inner Carniola with Postojna/Postumia and Ilirska Bistrica/Bisterza, and the Italian Province of Trieste, but not the Liburnian coast which was already part of Illyricum.[6]

Name

[edit]The name Istria (Ἰστρία) is derived from the river Ister (Ἴστρος) (modern Danube), because the Greeks erroneously believed, early in their travels around the Mediterranean, that a branch of the Danube flowed into the Adriatic Sea in that area. In addition, the Greeks called the inhabitants of the area Histri (Ἴστροι); if this was their native name, it may have initially led the Greeks to assume a connection with the river Ister.[7]

History

[edit]From prehistory to Roman times

[edit]

The name is derived from the Histri (Ancient Greek: Ἱστρών έθνος) tribes, which Strabo refers to as living in the region and who are credited as being the builders of the hillfort settlements (castellieri). The Histri are classified in some sources as a "Venetic" Illyrian tribe with certain linguistic differences from other Illyrians.[9] The Romans described the Histri as a fierce tribe of pirates, protected by the difficult navigation of their rocky coasts. It took two military campaigns for the Romans to finally subdue them in 177 BC. The region was then called together with the Venetian part the X. Roman Region of "Venetia et Histria", the ancient definition of the northeastern border of Italy. Dante Alighieri refers to it as well, the eastern border of Italy per ancient definition is the river Arsia. The eastern side of this river was settled by people whose culture was different from Histrians. Earlier influence of the Iapodes was attested there, while at some time between the 4th and 1st century BC the Liburnians extended their territory and it became a part of Liburnia.[10] On the northern side, Histria extended much further north and included the Italian city of Trieste.

Some scholars speculate that the names Histri and Istria are related to the Latin name Hister, or Danube (especially its lower course). Ancient folktales reported —inaccurately— that the Danube split in two or "bifurcated" and came to the sea near Trieste as well as at the Black Sea. The story of the "bifurcation of the Danube" is part of the Argonaut legend. There is also a suspected link (but no historical documentation in support of it) to the commune of Istria in Constanța, Romania which is named after the ancient city Histria, named after River Hister.

In the Early Middle Ages, Istria was conquered and occupied by the Goths. Ostrogoth coins were found in Istria, as well as the remains of some buildings. South of Poreč there are the remains of the church of Sv. Petar, erected in the 5th century (with a baptistery added later), which reportedly served the Arian eastern Goths ruling Istria.[11][12] Most notably, the Goths used Istrian stone to build their best known monument, the Mausoleum of Theodoric in Ravenna. In the following centuries, the peninsula was attacked and conquered by the Lombards, often in conjunction with the Slavs, such as in 601.[13] However, the extent to which the Lombards occupied Istria is a matter of debate. After the Goths, Istria became part of the Exarchate of Ravenna. Gulfaris, who served the Byzantines but was of Lombard descent, is reported as its dux in 599.[14][15]

Pope Gregory I in 600 wrote to bishop of Salona Maximus in which he expresses concern about arrival of the Slavs, "Et quidem de Sclavorum gente, quae vobis valde imminet, et affligor vehementer et conturbor. Affligor in his quae jam in vobis patior; conturbor, quia per Istriae aditum jam ad Italiam intrare coeperunt" (And as for the people of the Slavs who are really approaching you, I am very depressed and confused. I am depressed because I sympathize with you, confused because they over the Istria began to enter the Italy).[16] Some ancient reporters, including Pope Gregory, who were unaware of the importance of the Avars in the Balkans, used the terms "Slavs" to refer to the Avars or the Avaro-Slavs.[17]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the region was pillaged by the Goths, the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Avars.

Middle Ages

[edit]

The first Avaro-Slavic invasion of Istria was recorded in 599. Another major incursion occurred around 600–602, in which all of Istria was devastated with fire and rapine. This was followed by the 611 invasion, the most devastating for the peninsula. It remains unclear when and how the first Slavic settlement occurred. Traces of early Slavic incursions and settlement are scarce.[18] A few Avar findings have been discovered on the Istrian territory, chiefly around Nesactium.[19][20] By 642 the Slavs were settled in the peninsula, as indicated by the mission of an abbot Martin, sent by Pope John IV to rescue captives held by the pagans in Istria and Dalmatia.[18]

After the barbaric invasions, the western part of Istria was annexed to the Lombard Kingdom in 751, and then annexed to the Frankish kingdom by Pepin of Italy in 789. In 804, the Placitum of Riziano was held in the Parish of Rižan (Latin: Risanum), which was a meeting between the representatives of Istrian towns and castles and the deputies of Charlemagne and his son Pepin. The report about this judicial diet illustrates the changes accompanying the transfer of power from the Eastern Roman Empire to the Carolingian Empire and the discontent of the local residents.[21]

Afterwards it was successively controlled by the dukes of Carantania, Merania, Bavaria and by the patriarch of Aquileia, before it became the territory of the Republic of Venice in 1267. The medieval Croatian kingdom held only the far eastern part of Istria (the border was near the river Raša), but they lost it to the Holy Roman Empire in the late 11th century.

Venetian era

[edit]

Under Pietro II Candiano, who was Doge of Venice between 932 and 939, Istrian cities signed an act of devotion to the Venetian rule. On Ascension Day in 1000 a powerful fleet sailed from Venice to resolve the problem of the Narentine pirates.[22] The fleet visited all the main Istrian and Dalmatian cities, whose citizens, exhausted by the wars between the Croatian king Svetislav and his brother Cresimir, swore an oath of fidelity to Venice.[22] In 1145, the cities of Pula, Koper and Izola rose against the Republic of Venice but were defeated, and were since further controlled by Venice.[23] During the 13th century, the Patriarchate's rule weakened and the towns kept surrendering to Venice – Poreč in 1267, Umag in 1269, Novigrad in 1270, Sveti Lovreč in 1271, Motovun in 1278, Kopar in 1279, and Piran and Rovinj in 1283.[23] Venice gradually dominated the whole coastal area of western Istria and the area to Plomin on the eastern part of the peninsula.[23] The wealthier coastal towns cultivated increasingly strong economic relationships with Venice and by 1348 were eventually incorporated into its territory, while their inland counterparts fell under the sway of the weaker Patriarchate of Aquileia, which became part of the Habsburg Empire in 1374.

On 15 February 1267, Parenzo was formally incorporated with the Venetian state.[24] Other coastal towns followed shortly thereafter. Bajamonte Tiepolo was sent away from Venice in 1310, to start a new life in Istria after his downfall. A description of the 16th-century Istria with a precise map was prepared by the Italian geographer Pietro Coppo. A copy of the map inscribed in stone can now be seen in the Pietro Coppo Park in the center of the town of Izola in southwestern Slovenia.[25]

During the history of the coexistence of Slavic and Roman communities in Istria, the Slavs mostly lived in the interior, while the coast was Roman.[26]

Habsburg Monarchy (1797–1805)

[edit]The Inner part of Istria around Mitterburg (Pazin) had been part of the Holy Roman Empire for centuries, and more specifically part of the domains of the Austrian Habsburgs since the 14th century. In 1797, with the Treaty of Campo Formio, the Venetian parts of the peninsula also passed to the Habsburg monarchy which became the Austrian Empire in 1804.[27]

Napoleonic era (1805–1814)

[edit]

The French victory of 1809 compelled Austria to cede a portion of its South Slav lands to France. Napoleon combined Istira, Carniola, western Carinthia, Gorica (Gorizia), Trieste and parts of Croatia, Dalmatia, and Dubrovnik to form the Illyrian Provinces.[28] The Code Napoléon was introduced, and roads and schools were constructed. Local citizens were given administrative posts, and native languages were used to conduct official business.[28] This sparked the Illyrian Movement for the cultural and linguistic unification of South Slavic lands.[28] From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, Italian and Slavic communities in Istria had lived peacefully side by side because they did not know the national identification, given that they generically defined themselves as "Istrians" of "Romance" or "Slavic" culture.[29]

Austrian Empire (1814–1918)

[edit]

After this seven-year period, the Austrian Empire regained Istria, which became part of the constituent Kingdom of Illyria. This kingdom was broken up in 1849, after which Istria formed part of Austrian Littoral, also known as the "Küstenland", which also included the city of Trieste and the Princely County of Gorizia and Gradisca until 1918. At that time the borders of Istria included part of what is now Italian Venezia-Giulia and parts of modern-day Slovenia and Croatia, but not the city of Trieste.

Many Istrian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy.[30] However, after the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic. This triggered the gradual rise of Italian irredentism among many Italians in Istria, who demanded the unification of Istria with Italy. The Italians in Istria supported the Italian Risorgimento: as a consequence, the Austrians saw the Italians as enemies and favored the Slav communities of Istria,[31] fostering the nascent nationalism of Slovenes and Croats.[32]

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[33]

His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard. His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.

— Franz Joseph I of Austria, Council of the Crown of 12 November 1866[34]

Italy (1919–1947)

[edit]

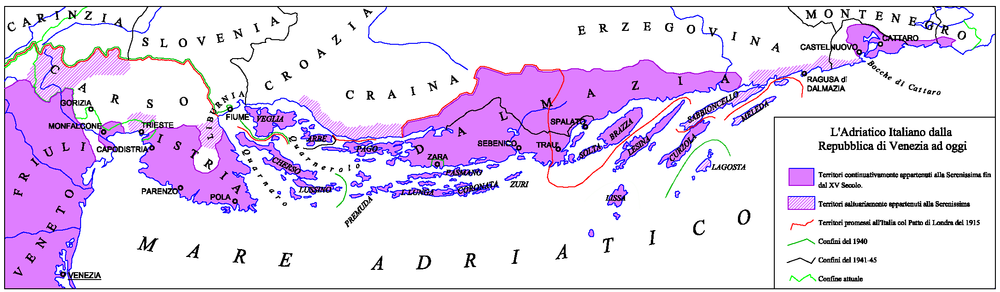

Although a member of the Central Powers, Italy remained neutral at the start of WWI, and soon launched secret negotiations with the Triple Entente, bargaining to participate in the war on its side, in exchange for significant territorial gains.[35] To get Italy to join the war, the secret 1915 Treaty of London the Entente promised Italy Istria and parts of Dalmatia, South Tyrol, the Greek Dodecanese Islands, parts of Albania and Turkey, plus more territory for Italy's North Africa colonies.

After the war, Italy annexed Istria. Istria's political and economic importance declined under Italian rule, and after the fascist takeover of Italy in 1922 the Italian government began a campaign of forced Italianization. In 1926, the use of Slavic languages in schools and government was banned, even Slavic family names were Italianized to suit the fascist authorities.[36] Slavic newspapers and libraries were closed, all Slavic cultural, sporting, business and political associations were banned. As a result, 100,000 Slavic-speakers left Italian-annexed areas in an exodus, moving mostly to Yugoslavia.[37]

The organization TIGR, founded in 1927 by young Slovene liberal nationalists from Gorizia region and Trieste and regarded as the first armed antifascist resistance group in Europe[38] soon penetrated into Slovene and Croatian-speaking parts of Istria.[39]

In World War II, Istria became a battleground of competing ethnic and political groups. Istrian nationalist groups which were pro-fascist and pro-Allied and Yugoslav-supported pro-communist groups fought with each other and the Italian army. After the German withdrawal in 1945, Yugoslav partisans gained the upper hand and began a violent purge of real or suspected opponents in an "orgy of revenge".[36]

SFR Yugoslavia (1947–1991)

[edit]

After the end of World War II, Istria was ceded to Yugoslavia, except for a small part in the northwest corner that formed Zone B of the provisionally independent Free Territory of Trieste; Zone B was under Yugoslav administration and after the de facto dissolution of the Free Territory in 1954 it was also incorporated into Yugoslavia. Only the small town of Muggia, near Trieste, being part of Zone A remained with Italy.[40]

The events of the period are visible in Pula. The city, located on the southernmost tip of the Istrian peninsula, had an Istrian Italian majority. Between December 1946 and September 1947, a large proportion of the city's inhabitants were forced to emigrate to Italy.[40] Most of them left in the immediate aftermath of the signing of the Paris Peace Treaty on February 10, 1947 which granted Pula and the greater part of Istria to Yugoslavia.

After the breakup of Yugoslavia (after 1991)

[edit]The division of Istria between Croatia and Slovenia runs on the former republic borders, which were not precisely defined in the former Yugoslavia. Various points of contention remain unresolved between the two countries regarding the precise line of the border.[41]

It became an international boundary with the independence of both countries from Yugoslavia in 1991. Since Croatia's first multi-party elections in 1990, the Istrian regionalist party Istrian Democratic Assembly (IDS-DDI, Istarski demokratski sabor or Dieta democratica istriana) has consistently received a majority of the vote and maintained through the 1990s a position often contrary to the government in Zagreb, led by the then nationalistic party Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ, Hrvatska demokratska zajednica), with regards to decentralization in Croatia and certain facets of regional autonomy.

However, that changed in 2000 when the IDS formed with five other parties a left-centre coalition government, led by the Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP, Socijaldemokratska Partija Hrvatske). After the reformed HDZ won the Croatian parliamentary elections in late 2003 and formed a minority government, the IDS has cooperated with the state government on many projects, both local (in Istria County) and national. Since Slovenia's accession to the European Union and the Schengen Area, customs and immigration checks have been abolished at the Italian-Slovenian border.

Demographic history

[edit]

The region has traditionally been ethnically mixed. Under Austrian rule in the 19th century it included a large population of Italians, Croats, and Slovenes as well as some Istro-Romanians, Serbs,[42] and Montenegrins; however, official statistics in those times did not show those nationalities as they do today.

The region has traditionally been ethnically mixed. Under Austrian rule in the 19th century it included a large population of Italians, Croats, and Slovenes as well as some Istro-Romanians, Serbs,[43] and Montenegrins; however, official statistics in those times did not show those nationalities as they do today.

The Croatian word for the Istrians is Istrani, or Istrijani, the latter being in the local Chakavian dialect. The term Istrani is also used in Slovenia. The Italian word for the Istrians is Istriani and today the Italian minority is organized in many towns.[44] The Istrian county in Croatia is bilingual, as are large parts of Slovenian Istria. Every citizen has the right to speak either Italian or Croatian (Slovene in Slovenian Istria and Italian in the town of Koper/Capodistria, Piran/Pirano, Portorož/Portorose, and Izola/Isola d'Istria) in public administration or in court. Furthermore, Istria is a supranational European Region that includes Italian, Slovenian and Croatian Istria.

The 2001 population census in Croatia counted 23 languages spoken by the people of Istria.[45][46] In 2021 Census show that 76.40% are Croats, Italians were 5.01%, 2.96% were Serbs, 2.48% Bosniaks, 1.05% were Albanians, while regionally declared were 5.13%.[47]

The data for Slovenian Istria is not as neatly organized, but the 2002 Slovenian census indicates that the four Istrian municipalities (Izola/Isola d'Istria, Piran/Pirano, Koper/Capodistria, Ankaran/Ancarano) had a total of 56,482 Slovenes, 6,426 Croats, and 2,800 Italians.[48]

The small town of Peroj has had a unique history which exemplifies the multi-ethnic complexity of the history of the region, as do some villages on both sides of the Učka that are still identified with the Istro-Romanian people which the UNESCO Redbook of Endangered Languages calls "the smallest ethnic group in Europe".[49]

Ethnicity

[edit]

There are some claims, Istrian Italians were more than 50% of the total population of Istria for centuries,[51] while making up about a third of the population in 1900.[52] With its strategic position at the southern tip of the peninsula and good harbor Pula was the primary base of the Austrian Navy.

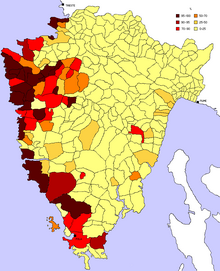

A limited tension with the Austrian state did not in fact stop the rise of the use of the Italian language, in the second part of the 19th century, when the population of predominantly Italian-speaking towns in Istria had a significant rise: in the part of Istria that eventually became part of Croatia, the first Austrian census from 1846 found 34 thousand Italian speakers, alongside 120 thousand Croatian speakers (in the Austrian censuses, the ethnic composition of the population was not surveyed, only the main "language of use" of a person). By 1910, the proportion changed significantly: there were 108 thousand Italian speakers and 134 thousand Croatian speakers.[53] Vanni D'Alessio notes (2008), the Austrian surveys of the language of use "overestimated the diffusion of the socially dominant languages of the empire... The capacity of assimilation of the Italian language suggests that amongst those who declared themselves Italian speakers in Istria, there were people whose mother tongue was different." D'Alessio notes even members of the Austrian state bureaucracy and the members of their families with the German mother tongue tended to use Italian, after living in Istrian small towns long enough. The Poles, Czechs and Slovenes and Croats tended to join the "Slav" social group.[54]

Discussions about Istrian ethnicity often use the words "Italian", "Croatian", and "Slovene" to describe the character of the Istrian people. However these terms are best understood as "national affiliations" that may exist in combination with or independently of linguistic, cultural and historical attributes. In the Istrian context, for example, the word "Italian" can just as easily refer to autochthonous speakers of the Venetian language whose antecedents in the region extend before the inception of the Venetian Republic or to the Istriot language the oldest spoken language in Istria, dated back to the Romans, today spoken in the southwest of Istria. It can also refer to Istrian Croats who adopted the veneer of Italian culture as they moved from rural to urban areas, or from the farms into the bourgeoisie.

Similarly, national powers claim Istrian Croats according to local language, so that speakers of Čakavian and Štokavian dialects of Croatian are considered to be Croatians while speakers of other dialects may be considered to be Slovene. Croatian dialect speakers are descendants of the refugees of the Turkish invasion and Ottoman Empire of Bosnia and Dalmatia in the 16th century.

The government of the Republic of Venice had settled them in Inner Istria, which had been devastated by wars and plague. As with other regions, the local dialects of the Croatian communities vary greatly across close distances. The Istrian Croatian and Italian vernaculars had both developed for many generations before being divided as they are today. This meant that Croats/Slovenes on the one side and Venetians/other Italians on the other side yielded to each other culturally while simultaneously distancing themselves from members of their ethnic groups living farther away.

Another important Istrian community are the Istro-Romanians in the south and north of the Učka mountain range of Istria. A small Albanian community, which until the late 19th century spoke the Istrian Albanian dialect is also present in the peninsula.

Austro-Hungarian census

[edit]According to Austro-Hungarian censuses, which recorded language instead of ethnicity, the composition of Istria (i.e. the Habsburg Margraviate of Istria) was as follows (in thousands):

| Language | 1846[55] | 1890[55] | 1910[56] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Croatian | 122 (56.7%) | 123 (42.4%) | 168 (43.5%) |

| Italian | 59 (27.4%) | 111 (38.3%) | 148 (38.1%) |

| Slovenian | 32 (14.9%) | 41 (14.1%) | 55 (14.3%) |

| German | n.a. | 15 (5.2%) | 13 (3.3%) |

Culture and cuisine

[edit]

The cuisine of Istria is influenced by Italian cuisine, given the historical presence of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians), influence that has eased after the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus.[57][58] For example, the influence of Italian cuisine on Croatian dishes can be seen in the pršut (similar to Italian prosciutto) and on the preparation of homemade pasta.[59] Traditional dishes of Italian origin also include gnocchi (njoki), risotto (rižot), focaccia (pogača), polenta (palenta), and brudet.[60] Slovenian dishes of Italian origin are njoki (similar to Italian gnocchi), rizota (the Slovenian version of risotto) and zilkrofi (similar to Italian ravioli).[61]

The Istrian stew (Italian: Jota; Croatian: Istarska jota; Slovene: Jota) is a soup made with beans and sauerkraut or sour turnip, potatoes, bacon, and spare ribs, known in the northern Adriatic regions.[62] Under the name jota, it is typical and especially popular in Trieste and its province (where it is considered to be the prime example of Triestine food), in the Istrian peninsula, in the province of Gorizia, in the whole Slovenian Littoral, in the Rijeka area, and in Friuli, especially in some of its peripheral areas (the highland region of Carnia, the Torre and Natisone river valleys, or Slavia Veneta). The stew, based on etymology, most likely originated in Friuli before spreading east and south.

Istrian identity, also known as Istrianity,[63] Istrianism[64] or Istrianness,[55] is the regionalist identity developed by the inhabitants of the part of Istria located in Croatia. Istria is the biggest peninsula in the Adriatic Sea and a multiethnic region divided between Croatia, Italy and Slovenia. Italians and Slovenes live in both the Italian and Slovene parts (which make up 1% and 9% of the territory of Istria, respectively), while in the Croatian part (90% of the region), there are Croats, Italians, Istro-Romanians and Istriot-speakers, as well as some non-native minorities. Most of Croatian Istria is located in the Istria County of the country. Istria is the region of Croatia where regionalist sentiment is the strongest.[64]

In the 2011 Croatian census, 25,203[65] people of the Istria County, constituting 12% of its population, declared themselves to be Istrian before any other nationality, making it the most abundant one in the county after Croatian. People also declared an Istrian identity in the Primorje-Gorski Kotar County, the county where the rest of Croatian Istria is located,[55] therefore making the number of people declaring an Istrian identity in Croatia a total of 25,409.[65] Most of these people in these counties were ethnic Croats, but there were also Istro-Romanians declaring themselves as Istrian.[55] Later, the 2021 Croatian census saw a decrease on Istrian self-designation, as 10,025 inhabitants of the Istria County used it.[66]

It has been proposed that Istria gain greater autonomy within a more decentralized Croatia. Examples of supporters of this include several members of the Istrian Democratic Assembly (IDS), such as its former president Boris Miletić[67] or the IDS deputy Emil Daus.[68]

Image gallery

[edit]-

Aerial picture of Pula (Pola), Croatia

-

The promenade of Poreč (Parenzo), Croatia

-

Sunset in Rovinj (Rovigno), Croatia

-

The Motovun (Montona) Hill, Croatia

-

Lim canal (fjord), Croatia

-

The Praetorian Palace in Koper (Capodistria), Slovenia

-

Old town of Piran (Pirano), (Slovenia)

-

Muggia, Italy

-

Traditional folk costume of Istrian Croats

-

Vineyards of Istria

Major towns and municipalities of Istria

[edit]This list includes towns and municipalities of Istria with populations estimated to be higher than 8,000 people.[69]

- Koper/Capodistria

- Pula/Pola

- Poreč/Parenzo

- Rovinj/Rovigno

- Izola/Isola

- Umag/Umago

- Muggia/Milje

- Labin/Albona

- Pazin/Pisino

See also

[edit]- Castellieri culture

- List of Istrians

- March of Istria

- Istrian–Dalmatian exodus

- Istrian Italians

- Acta Histriae

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ a b Marcel Cornis-Pope, John Neubauer, History of the literary cultures of East-Central Europe: junctures and disjunctures in the 19th And 20th Centuries, John Benjamins Publishing Co. (2006), ISBN 90-272-3453-1

- ^ a b Alan John Day, Roger East, Richard Thomas, A political and economic dictionary of Eastern Europe, Routledge, 1sr ed. (2002), ISBN 1-85743-063-8

- ^ "Geographic data". www.istra-istria.hr. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ^ Istria, Croatia (2021-05-18). "Istria". National Park Brijuni Excursions. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ Hrpelje-Kozina municipal site Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Leonhard Schmitz, A manual of ancient geography, pg. 131, The British Library (2010), ISBN B003MNGWVI

- ^ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), Istria

- ^ Džin, Kristina (2009). Žužić, Mirko (ed.). Arena Pula. Zagreb: Viza MG d.o.o. p. 7. ISBN 978-953-7422-15-8.

- ^ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians, 1992,ISBN 0-631-19807-5, page 183,"... We may begin with the Venetic peoples, Veneti, Carni, Histri and Liburni, whose language set them apart from the rest of the Illyrians...."

- ^ M. Blečić, Prilog poznavanju antičke Tarsatike, VAMZ, 3.s., XXXIV 65-122 (2001), UDK 904:72.032 (3:497.5), pages 70, 71

- ^ Šonje, Ante. Crkvena arhitektura (L'architettura sacra). pp. 45–49, 217, 270.

- ^ Bratož, Rajko (1989). The development of the early Christian research in Slovenia and Istria between 1976 and 1986 [article] Lyon, Vienne, Grenoble, Genève, Aoste, 21-28 septembre 1986. Publications de l'École Française de Rome. p. 2370.

- ^ Mengoli, Liliana Martissa (7 March 2016). "Alto Medioevo". Coordinamento Adriatico. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Gregory's letter to Gulfaris at Catholic Culture". Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Martyn, John R. C (2012). Pope Gregory's Letter-Bearers: A Study of the Men and Women who carried letters for Pope Gregory the Great. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-443-83918-1.

- ^ Željko Rapanić; (2013) O početcima i nastajanju Dubrovnika (The origin and formation of Dubrovnik. additional considerations) p. 94; Starohrvatska prosvjeta, Vol. III No. 40, [1]

- ^ Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, C.500–700. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9781139428880.

- ^ a b Bekic, Luka (2016). The Early Medieval Between Pannonia and the Adriatic. Archaeological Museum of Istria. pp. 1–301.

- ^ Štih, Peter (2010). The Middle Ages Between the Eastern Alps and the Northern Adriatic. Brill. p. 198. ISBN 9789004187702.

- ^ Begic, Vanesa. "AVARI I SLAVENI JUŽNO OD DRAVE: Vitrina s dva avarska predmeta iz Arheološkog muzeja Istre". Glas Istre.

- ^ Oto Luthar, ed. (2008). The land between: a history of Slovenia. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. p. 100. ISBN 978-3-631-57011-1.

- ^ a b "ORSEOLO, Pietro II in "Dizionario Biografico"". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2017-09-15.

- ^ a b c Istra-Istria.hr, VARIOUS RULERS.

- ^ John Mason Neale, Notes Ecclesiological & Picturesque on Dalmatia, Croatia, Istria, Styria, with a visit to Montenegro, pg. 76, J.T. Hayes - London (1861)

- ^ "Historic Urban Cores: Izola". REVITAS – Revitalisation of the Istrian hinterland and tourism in the Istrian hinterland. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Ivetić, Eđidio (2015). GRANICA NA MEDITERANU. ISTOČNI JADRAN IZMEĐU ITALIJE I JUŽNOSLOVENSKOG SVETA OD XIII DO XX VEKA. Arhipelag. p. 99.

- ^ Stephens, Henry Morse (2008). Revolutionary Europe, 1789–1815, BiblioLife. p. 192. ISBN 0-559-25438-5.

- ^ a b c "Illyrian Provinces | historical region, Europe | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ ""L'Adriatico orientale e la sterile ricerca delle nazionalità delle persone" di Kristijan Knez; La Voce del Popolo (quotidiano di Fiume) del 2/10/2002" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ "Trieste, Istria, Fiume e Dalmazia: una terra contesa" (in Italian). Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971

- ^ Relazione della Commissione storico-culturale italo-slovena, Relazioni italo-slovene 1880-1956, "Capitolo 1980-1918" Archived 13 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Capodistria, 2000

- ^ Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971, vol. 2, p. 297. Citazione completa della fonte e traduzione in Luciano Monzali, Italiani di Dalmazia. Dal Risorgimento alla Grande Guerra, Le Lettere, Firenze 2004, p. 69.)

- ^ Jürgen Baurmann, Hartmut Gunther and Ulrich Knoop (1993). Homo scribens: Perspektiven der Schriftlichkeitsforschung (in German). Walter de Gruyter. p. 279. ISBN 3484311347.

- ^ Cattaruzza, Marina (2011). "The Making and Remaking of a Boundary – the Redrafting of the Eastern Border of Italy after the two World Wars". Journal of Modern European History / Zeitschrift für moderne europäische Geschichte / Revue d'histoire européenne contemporaine. 9 (1): 66–86. doi:10.17104/1611-8944_2011_1_66. ISSN 1611-8944. JSTOR 26265925. S2CID 145685085.

- ^ a b Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 340–341. ISBN 978-0313309847.

- ^ "dLib.si - Izseljevanje iz Primorske med obema vojnama". www.dlib.si. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- ^ Office of the President of the Republic of Slovenia (5 May 2010). "President Hails Heroism of Slovenian WWII Patriots". Government Communication Office. Retrieved 9 September 2010. [permanent dead link]

- ^ Rawson, Andrew (2013). Organizing Victory: The War Conferences 1941–1945. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: History Press. ISBN 9780752489254.

- ^ a b Katia Pizzi, A city in search of an author: the literacy identity of Trieste, pg. 23, Sheffield Academic Press (2002), ISBN 1-84127-284-1

- ^ Julio Aramberri, Richard Butler, Tourism Development, pg. 195

- ^ see also Census 2001

- ^ see also Census 2001

- ^ Italian Istria infosite Archived 2014-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, unione-italiana.hr; accessed 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Istria on the Internet – Demography – 2001 Census". Retrieved 4 September 2015. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census: County of Istria". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ^ "Results" (xlsx). Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in 2021. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2022.

- ^ Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia Archived 2009-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, Population Census 2002 results, stat.si; accessed 4 August 2015.

- ^ Salminen, Tapani (1999). "UNESCO Red Book on Endangered Languages". Helsinki.fi. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ Klein-Pejšová, Rebekah (12 February 2015). Mapping Jewish Loyalties in Interwar Slovakia. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253015624. Retrieved 4 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Istrian Spring". Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 886–887.

- ^ Žerjavić, Vladimir (2008). "DOSELJAVANJA I ISELJAVANJA S PODRUČJA ISTRE, RIJEKE I ZADRA U RAZDOBLJU 1910-1971". Journal of Modern Italian Studies. 13 (2): 237–258.

- ^ D'Alessio, Vanni (2008). "From Central Europe to the northern Adriatic: Habsburg citizens between Italians and Croats in Istria". Journal of Modern Italian Studies. 13 (2): 237–258. doi:10.1080/13545710802010990. S2CID 145797119.

- ^ a b c d e Žerjavić, Vladimir (1993-07-01). "DOSELJAVANJA I ISELJAVANJA S PODRUČJA ISTRE, RIJEKE I ZADRA U RAZDOBLJU 1910-1971". Društvena istraživanja: časopis za opća društvena pitanja (in Croatian). 2 (4-5 (6-7)): 649. ISSN 1330-0288.

- ^ "Spezialortsrepertorium der österreichischen Länder I-XII, Wien, 1915–1919". Archived from the original on 2013-05-29. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- ^ "Cucina Croata. I piatti della cucina della Croazia" (in Italian). 19 June 2016. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "I sopravvissuti: i 10 gioielli della cucina istriana" (in Italian). 23 March 2016. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Assaporate il cibo dell'Istria: il paradiso gastronomico della Croazia" (in Italian). 21 May 2019. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Danieli, Susanna (2020-08-27). "I 20 piatti tipici della Croazia da non perdersi". Dissapore (in Italian). Retrieved 2024-06-28.

- ^ "La cucina slovena" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Maneštre (Eintopf) | Molo Grande Travel". 2014-12-09. Archived from the original on 2014-12-09. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- ^ Stjepanović, Dejan (2018). Multiethnic Regionalisms in Southeastern Europe. Comparative Territorial Politics. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-58585-1. ISBN 9781137585851.

- ^ a b Pauković, Donatella (25 February 2021). "People also ask Google: What language do they speak in Istria?". Total Croatia News. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Popis stanovništva, kućanstava i stanova 2011" (PDF) (in Croatian). Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2013. ISSN 1333-1876.

- ^ "Popis '21" (in Croatian). Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2021. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ Boban Valečić, Iva (27 October 2017). "Autonomija Istre kakvu zaziva Jakovčić je neustavna". Večernji list (in Croatian).

- ^ "IDS-ov zastupnik Emil Daus: AUTONOMIJA ISTRE RIJEŠILA BI VEĆINU PROBLEMA NAŠIH GRAĐANA!". Glas Istre (in Croatian). 23 September 2019.

- ^ "Istra (County, Croatia) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

Further reading

[edit]- Ashbrook, John (December 2005). "Self-perceptions, denials, and expressions: Istrianity in a nationalizing Croatia, 1990-1997". Nationalities Papers. 33 (4): 459–487. doi:10.1080/00905990500353923. S2CID 143942069.

- Luigi Tomaz, Il confine d'Italia in Istria e Dalmazia. Duemila anni di storia, Presentazione di Arnaldo Mauri, Think ADV, Conselve 2008.

- Luigi Tomaz, In Adriatico nel secondo millennio, Presentazione di Arnaldo Mauri, Think ADV, Conselve, 2010.

- Louis François Cassas "Travels in Istria and Dalmatia, drawn up from the itinerary of L. F. Cassas" Eng trans. from 1802 Fr pub.

- "Istria Between Purity and Hybridity: The Creation of the Istrian Region Through Scientific Research in the 19th Century". www.academia.edu. Istria County. Retrieved 2018-12-19.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Istria on the Internet (a non-commercial, non-political, cultural site)

- Old postcards of Istria

- A Brief History of Istria / Darko Darovec

- Results of Austrian Census on Dec. 31st, 1910 Archived 2018-03-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Istrian cultural heritage. Bukaleta Kazun, wall paintings

- Travels in Istria and Dalmatia: drawn up from the itinerary of L. F. Cassas on Google Books

45°15′40″N 13°54′16″E / 45.26111°N 13.90444°E