The Lord of the Rings (1978 film)

| The Lord of the Rings | |

|---|---|

| |

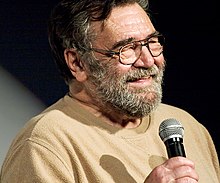

| Directed by | Ralph Bakshi |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Produced by | Saul Zaentz |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Timothy Galfas |

| Edited by | Donald W. Ernst |

| Music by | Leonard Rosenman[2] |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 133 minutes[3] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4 million[2] |

| Box office | $32.6 million[3][5] |

The Lord of the Rings is a 1978 animated epic fantasy film directed by Ralph Bakshi from a screenplay by Chris Conkling and Peter S. Beagle. It is based on the novel of the same name by J. R. R. Tolkien, adapting from the volumes The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers.[6] Set in Middle-earth, the film follows a group of fantasy races—Hobbits, Men, an Elf, a Dwarf and a wizard—who form a fellowship to destroy a magical ring made by the Dark Lord Sauron, the main antagonist.

Bakshi encountered Tolkien's writing early in his career. He had made several attempts to produce The Lord of the Rings as an animated film before producer Saul Zaentz and distributor United Artists provided funding. The film is notable for its extensive use of rotoscoping, a technique in which scenes are first shot in live-action, then traced onto animation cels. It uses a hybrid of traditional cel animation and rotoscoped live-action footage.[7]

The Lord of the Rings was released in the United States on November 15, 1978, and in the United Kingdom on July 5, 1979. Although the film received mixed reviews from critics, and hostility from disappointed viewers who felt that it was incomplete, it was a financial success; there was no official sequel to cover the remainder of the story. However, the film has retained a cult following and was a major inspiration for New Zealand filmmaker Peter Jackson.

Plot

[edit]Early in the Second Age of Middle-earth, Elven smiths forge nine Rings of Power for mortal Men, seven for the Dwarf-Lords, and three for the Elf-Kings. Soon after, the Dark Lord Sauron makes the One Ring, and uses it to attempt to conquer Middle-earth. After defeating Sauron, Prince Isildur takes the Ring, but after he is eventually killed by Orcs, the Ring lies at the bottom of the river Anduin for over 2,500 years. Over time, Sauron captures the Nine Rings and transforms their owners into the Ringwraiths. The One Ring is discovered by Déagol, whose kinsman, Sméagol, kills him and takes the Ring for himself. The Ring twists his body and mind, and he becomes the creature Gollum (Peter Woodthorpe) who takes it with him into the Misty Mountains. Hundreds of years later, Bilbo Baggins (Norman Bird) finds the Ring in Gollum's cave and brings it back with him to the Shire.

Decades later, during Bilbo's birthday celebration, the Wizard Gandalf (William Squire) tells him to leave the Ring for his nephew Frodo (Christopher Guard). Bilbo reluctantly agrees, and departs for Rivendell. Seventeen years pass, during which Gandalf learns that evil forces have discovered that the Ring is in the possession of a Baggins. Gandalf meets Frodo to explain the Ring's history and the danger it poses, and Frodo leaves his home, taking the Ring with him. He is accompanied by three Hobbits, his cousins, Pippin (Dominic Guard), Merry (Simon Chandler), and his gardener Sam (Michael Scholes). After a narrow escape from the Ringwraiths, the hobbits eventually come to Bree, from which Aragorn (John Hurt) leads them to Rivendell. Frodo is stabbed atop Weathertop mountain by the chief of the Ringwraiths, and becomes sickened as the journey progresses. The Ringwraiths catch up with them shortly after they meet the Elf Legolas (Anthony Daniels); and at a standoff at the ford of Rivendell, the Ringwraiths are swept away by the river.

At Rivendell, Frodo is healed by Elrond (André Morell). He meets Gandalf again, after the latter escapes the corrupt wizard Saruman (Fraser Kerr), who plans to ally with Sauron but also wants the Ring for himself. Frodo volunteers to go to Mordor, where the Ring can be destroyed. Thereafter Frodo sets off from Rivendell with eight companions: Gandalf; Aragorn; Boromir (Michael Graham Cox), son of the Steward of Gondor; Legolas; Gimli (David Buck) the Dwarf, along with Pippin, Merry, and Sam.

Their attempt to cross the Misty Mountains is foiled by heavy snow, and they are forced into Moria. There, they are attacked by Orcs, and Gandalf falls into an abyss while battling a Balrog. The remaining Fellowship continue through the Elf-haven Lothlórien, where they meet the Elf queen Galadriel (Annette Crosbie). Boromir tries to take the Ring from Frodo, and Frodo decides to continue his quest alone; but Sam insists on accompanying him. Boromir is killed by Orcs while trying to defend Merry and Pippin. Merry and Pippin are captured by the Orcs, who intend to take them to Isengard through the land of Rohan. The captured hobbits escape and flee into Fangorn Forest, where they meet Treebeard (John Westbrook). Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas track Merry and Pippin into the forest, where they are reunited with Gandalf, who was reborn after destroying the Balrog.

The four then ride to Rohan's capital, Edoras, where Gandalf persuades King Théoden (Philip Stone) that his people are in danger. Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas then travel to the Helm's Deep. Frodo and Sam discover Gollum stalking them in an attempt to reclaim the Ring, and capture him; but spare his life in return for guidance to Mount Doom. Gollum eventually begins plotting against them, and wonders if "she" might help. At Helm's Deep, Théoden's forces resist the Orcs sent by Saruman, until Gandalf arrives with the absent Riders of Rohan, destroying the Orc army.

Cast

[edit]- Christopher Guard as Frodo

- William Squire as Gandalf

- Michael Scholes as Sam

- John Hurt as Aragorn

- Simon Chandler as Merry[8]

- Dominic Guard as Pippin

- Norman Bird as Bilbo

- Michael Graham Cox as Boromir

- Anthony Daniels as Legolas

- David Buck as Gimli

- Peter Woodthorpe as Gollum

- Fraser Kerr as Saruman

- Philip Stone as Théoden

- Michael Deacon as Wormtongue

- André Morell as Elrond

- Alan Tilvern as Innkeeper

- Annette Crosbie as Galadriel

- John Westbrook as Treebeard / Lord Celeborn of Lothlorien[2]

This primary cast was supported by a large cast of animation doubles, who were not credited on screen; the matter went to guild arbitration.[9]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Director Ralph Bakshi was introduced to The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien during the mid-1950s while working as an animator for Terrytoons. In 1957, the young animator started trying to convince people that the story could be told in animation.[10]

In 1969, the rights were passed to United Artists, where an "elegant" Peter Shaffer script was abandoned. Film producer Denis O'Dell was interested in producing a film for the Beatles, and approached directors David Lean (busy with Ryan's Daughter), Stanley Kubrick (who deemed it "unfilmable"), and Michelangelo Antonioni. John Boorman was commissioned to write a script in late 1969, but it was deemed too expensive in 1970.[2]

Bakshi approached United Artists when he learned (from a 1974 issue of Variety) that Boorman's script was abandoned. Learning that Boorman intended to produce all three parts of The Lord of the Rings as a single film, Bakshi commented, "I thought that was madness, certainly a lack of character on Boorman's part. Why would you want to tamper with anything Tolkien did?"[11] Bakshi began making a "yearly trek" to United Artists. Bakshi had since achieved box office success producing adult-oriented animated films such as Fritz the Cat but his recent film, Coonskin, tanked, and he later clarified that he thought The Lord of the Rings could "make some money" so as to save his studio.[12]

In 1975, Bakshi convinced United Artists executive Mike Medavoy to produce The Lord of the Rings as two or three animated films,[13] and a prequel to The Hobbit.[14] Medavoy offered him Boorman's script, which Bakshi refused, saying that Boorman "didn't understand it"[15] and that his script would have made for a cheap film like "a Roger Corman film".[16] Medavoy accepted Bakshi's proposal to "do the books as close as we can, using Tolkien's exact dialogue and scenes".[11]

Although he was later keen to regroup with Boorman for his script (and his surrogate project, Excalibur), Bakshi claimed Medavoy did not want to produce his film at the time, but allowed him to shop it around if he could get another studio to pay for the expenses on Boorman's script.[16] Bakshi attempted unsuccessfully to persuade Peter Bogdanovich to take on the project, but managed to gain the support of the then President of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Dan Melnick.[16][11] Bakshi and Melnick made a deal with Mike Medavoy at United Artists to buy the Boorman script. Bakshi said later that "The Boorman script cost $3 million, so Boorman was happy by the pool, screaming and laughing and drinking, 'cause he got $3 million for his script to be thrown out."[11] Boorman, however, was unhappy with the project going to animation after Tolkien once wrote to him, pleased that he was doing it in live-action. He never saw Bakshi's film, and after it was released, tried to remake his live-action version with Medavoy.[17]

Work began on scripts and storyboards. When Melnick was fired from MGM in 1976, Bakshi's studio had spent between $200,000 and $600,000. The new executive Dick Shepherd had not read the books and, according to Bakshi, did not want to make the movie;[16] Shepherd obliviously asked whether The Lord of the Rings was about a wedding.[16] Bakshi then contacted Saul Zaentz (who had helped finance Fritz the Cat), asking him to produce The Lord of the Rings; Zaentz agreed.[11]

Before production started, Bakshi met with Tolkien's daughter Priscilla to discuss how the film would be made. She showed him the room where her father did his writing and drawing. Bakshi says, "My promise to Tolkien's daughter was to be pure to the book. I wasn't going to say, 'Hey, throw out Gollum and change these two characters.' My job was to say, 'This is what the genius said.'"[18]

Bakshi was approached by Mick Jagger,[16] who wanted to play Frodo, but at the time the roles were already cast and recorded. David Carradine[15] also approached Bakshi, offering to play Aragorn, and even suggested that Bakshi do it in live-action; while Bakshi's contract allowed this, he said it could not be done and that he had "always seen it as animation".[13] He said it was impossible to make it in live-action without it being "tacky".[15]

Screenwriting

[edit]Bakshi began developing the script himself. Learning of the project, Chris Conkling got an interview with Bakshi but was initially hired to "do research, to say what the costumes should look like or what the characters would be doing at any given time".[19] Together, they first decided how to break the films down. When they started, they contemplated a three-film structure, but "we didn't know how that middle film would work"[20] without a beginning and an end. Conkling even started writing a treatment for one long, three-and-a-half hour feature of the entire work, but eventually settled on scripts for two 150-minute films, the first of which was titled "The Lord of the Rings, Part One: The Fellowship".[21]

The second draft[20] of the screenplay, written by Conkling,[2] told the bulk of the story in flashback, from Merry Brandybuck's point of view, so as to lead into the sequel.[22][21] This version included Tom Bombadil, who rescues the Hobbits from the Barrow Downs,[21] as well as Farmer Maggot, the Old Forest, Glorfindel, Arwen, and several songs.[20][21] Bakshi felt it was "a much too drastic departure from Tolkien".[22] Conkling began writing a draft that was "more straightforward and true to the source".[22]

Still displeased, Bakshi and Zaentz called in fantasy author Peter S. Beagle for a rewrite.[2][22] Beagle's first draft eliminated the framing device and told the story beginning with Bilbo's Farewell Party, climaxing with the Battle of Helm's Deep, and ending with the cliffhanger of Gollum leading Frodo and Sam to Shelob. The revised draft includes a brief prologue to reveal the history of the Ring.[22] Fans threatened Bakshi that "he'd better get it right"[19] and according to the artist Mike Ploog, Bakshi constantly revised the story to include certain beasts at the behest of such fans.[23]

Differences from the book

[edit]Of the adaptation process, Bakshi stated that some elements of the story "had to be left out but nothing in the story was really altered".[10] The film greatly condenses Frodo's journey from Bag End to Bree. Stop-overs at Farmer Maggot's house, Frodo's supposed home in Buckland, and the house of the mysterious Tom Bombadil deep in the Old Forest are omitted. Maggot and his family, Bombadil and his wife Goldberry and the encounter with the Barrow-wight are thus all omitted, along with Fatty Bolger, a hobbit who accompanied Frodo at the beginning. According to Bakshi, the character of Tom Bombadil was dropped because "he didn't move the story along."[10]

Directing

[edit]

Bakshi said that one of the problems with the production was that the film was an epic, because "epics tend to drag. The biggest challenge was to be true to the book."[10] When asked what he was trying to accomplish with the film, Bakshi stated "The goal was to bring as much quality as possible to the work. I wanted real illustration as opposed to cartoons."[10] Bakshi said that descriptions of the characters were not included because they are seen in the film. He stated that the key thing was not "how a hobbit looks", since everyone has their own idea of such things, but that "the energy of Tolkien survives".[10] In his view what mattered was whether the quality of animation was enough to make the movie work.[10]

Bakshi was aware of the work of illustrators like the Brothers Hildebrandt, without accepting that their style had driven his approach;[24] he stated that the film presented a clash of many styles, as in his other films.[10]

Animation

[edit]Publicity for the film announced that Bakshi had created "the first movie painting" by utilizing "an entirely new technique in filmmaking".[10] Much of the film used live-action footage which was then rotoscoped to produce an animated look.[10] This saved production costs and gave the animated characters a more realistic look. In animation historian Jerry Beck's The Animated Movie Guide, reviewer Marea Boylan writes that "up to that point, animated films had not depicted extensive battle scenes with hundreds of characters. By using the rotoscope, Bakshi could trace highly complex scenes from live-action footage and transform them into animation, thereby taking advantage of the complexity live-action film could capture without incurring the exorbitant costs of producing a live-action film."[2] Bakshi rejected the Disney approach which he thought "cartoony", arguing that his approach, while not traditional for rotoscoping, created a feeling of realism involving up to a thousand characters in a scene.[10]

Bakshi went to England to recruit a voice cast from the BBC Drama Repertory Company, including Christopher Guard, William Squire, Michael Scholes, Anthony Daniels, and John Hurt. Daniels remembers that "The whole cast were in the same studio but we all had to leave a two second gap between the lines which made for rather stilted dialogue."[25] For the live-action portion of the production, Bakshi and his cast and crew went to Spain, where the rotoscope models acted out their parts in costume in the open or in empty soundstages. Additional photography took place in Death Valley. Bakshi was so terrified of the horses used in the shoot that he directed those scenes from inside the caravan.[23]

Bakshi had a difficult working relationship with producer Saul Zaentz. When Zaentz would bring potential investors to Bakshi's studio, he would always show them the same sequence, of Frodo falling off of his horse at the Ford (which was his stunt double actually falling over).[23]

During the middle of a large shoot, union bosses called for a lunch break, and Bakshi secretly shot footage of actors in Orc costumes moving toward the craft service table, and used the footage in the film.[26] Many of the actors who contributed voices to this production also acted out their parts for rotoscoped scenes. The actions of Bilbo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee were performed by Billy Barty, while Sharon Baird served as the performance model for Frodo Baggins.[2] Other performers used on the rotoscoping session included John A. Neris as Gandalf, Walt Robles as Aragorn, Felix Silla as Gollum, Jeri Lea Ray as Galadriel, and Aesop Aquarian as Gimli. Although some cel animation was produced and shot for the film,[27][28] very little of it appears in the final film. Most of the film's crowd and battle scenes use a different technique, in which live-action footage is solarized (per an interview with the film's cinematographer, Timothy Galfas, in the documentary Forging Through the Darkness: the Ralph Bakshi Vision for The Lord of the Rings) to produce a more three-dimensional look. In a few shots the two techniques are combined.[19]

Bakshi claimed he "didn't start thinking about shooting the film totally in live action until I saw it really start to work so well. I learned lots of things about the process, like rippling. One scene, some figures were standing on a hill and a big gust of wind came up and the shadows moved back and forth on the clothes and it was unbelievable in animation. I don't think I could get the feeling of cold on the screen without showing snow or an icicle on some guy's nose. The characters have weight and they move correctly."[10] After the Spanish film development lab discovered that telephone lines, helicopters, and cars could be seen in the footage Bakshi had shot, they tried to incinerate the footage, telling Bakshi's first assistant director that "if that kind of sloppy cinematography got out, no one from Hollywood would ever come back to Spain to shoot again."[26]

Following the live-action shoot, each frame of the live footage was printed out, and placed behind an animation cel. The details of each frame were copied and painted onto the cel. Both the live-action and animated sequences were storyboarded.[29] Of the production, Bakshi is quoted as saying,

Making two pictures [the live action reference and the actual animated feature] in two years is crazy. Most directors when they finish editing, they are finished; we were just starting. I got more than I expected. The crew is young. The crew loves it. If the crew loves it, it's usually a great sign. They aren't older animators trying to snow me for jobs next year.[10]

Although he continued to use rotoscoping in American Pop, Hey Good Lookin', and Fire and Ice, Bakshi later regretted his use of the technique, stating that he felt that it was a mistake to trace the source footage rather than using it as a guide.[30]

By the time Bakshi was done animating, he had only four weeks left to cut the film[16] from a nearly 150-minute[31] rough cut. Restoring a piece of animation where Gandalf fights the Balrog (replaced in the finished film by a photomontage), Eddie Bakshi remarked that little of the film was left on the cutting room floor. Bakshi asked three additional months to edit the film, but was declined.[16] After test-screenings, it was decided to re-cut the end of the picture so that Gollum would resolve leading Frodo and Sam to Shelob before cutting back to Helm's Deep, so as to not end the film on a cliffhanger.[20][22]

Working on the film were Tim Burton, Disney animator Dale Baer, and Mike Ploog, who worked also on other Bakshi animations such as Wizards.[32]

Music

[edit]The film score was composed by Leonard Rosenman.[2] Bakshi wanted to include music by Led Zeppelin but producer Saul Zaentz insisted upon an orchestral score because he would not be able to release the band's music on his Fantasy Records label. Rosenman wanted a large score, involving a 100-piece orchestra, 100-piece mixed choir and 100-piece boy choir,[33] but ended up with a smaller ensemble. Bakshi initially called his score "majestic",[24] but later stated that he hated Rosenman's score, which he found to be too cliché.[34]

In Lord of the Rings: Popular Culture in Global Context, Ernest Mathijs writes that Rosenman's score "is a middle ground between his more sonorous but dissonant earlier scores and his more traditional (and less challenging) sounding music [...] In the final analysis, Rosenman's score has little that marks it out as distinctively about Middle Earth, relying on traditions of music (including film music) more than any specific attempt to paint a musical picture of the different lands and peoples of Tolkien's imagination."[35] The film's score was issued as a double-LP soundtrack album in 1978.[36] The album reached number 33 in the Canadian RPM Magazine album charts on February 24, 1979.[37]

Reception

[edit]Box office, awards and nominations

[edit]The Lord of the Rings was a financial success.[38] Reports of the budget vary from $4[2] to $8 million, and as high as $12 million,[39] while the film grossed $30.5 million at the North American box office. It thus made a profit, having kept its costs low.[2] In the United Kingdom, the film grossed over $3.2 million.[5] Despite this, the reaction from fans was hostile; Jerry Beck writes that they "intensely dislike[d]" the film's "cheap-looking effects and the missing ending", having been misled by the title to expect the film to cover the whole of the book.[2]

The film was nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.[40] It was nominated for a Saturn Awards for Best Fantasy Film.[16] Leonard Rosenman's score was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Original Motion Picture Score, and Bakshi won a Golden Gryphon award for the film at the Giffoni Film Festival.[16]

Critical response

[edit]Critics gave mixed responses to the film, but generally considered it to be a "flawed but inspired interpretation".[2] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 49% based on 45 reviews, with an average of 5.5/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Ralph Bakshi's valiant attempt at rendering Tolkien's magnum opus in rotoscope never lives up to the grandeur of its source material, with a compressed running time that flattens the sweeping story and experimental animation that is more bizarre than magical."[41]

Frank Barrow of The Hollywood Reporter wrote that the film was "daring and unusual in concept".[2] Joseph Gelmis of Newsday wrote that "the film's principal reward is a visual experience unlike anything that other animated features are doing at the moment."[2] Roger Ebert called Bakshi's effort a "mixed blessing" and "an entirely respectable, occasionally impressive job ... [which] still falls far short of the charm and sweep of the original story."[42] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "both numbing and impressive".[43]

David Denby of New York magazine felt that the film would not make sense to viewers who had not previously read the book. Denby wrote that the film was too dark and lacked humour, concluding that "The lurid, meaningless violence of this movie left me exhausted and sickened by the end."[44] Michael Barrier, an animation historian, described The Lord of The Rings as one of two films that demonstrated "that Bakshi was utterly lacking in the artistic self-discipline that might have permitted him to outgrow his limitations."[45]

Barry Langford, writing in the J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, noted the film's deficiencies, including the "glaringly evident"[9] weaknesses in the rotoscoping animation. The quality of rotoscoping from filmed live action is limited by the quality of the acting, which, given the lack of rehearsal and time for retakes, was not high. The prologue was not rotoscoped, but shot as "silhouetted dumb show through red filters",[9] revealing clumsy mime and confused voiceover, announcing that Mordor defeated Elves and Men at the Battle of Dagorlad, which Langford observes would make the rest of the action incomprehensible. The small budget led to underwhelming battle scenes, as in the Mines of Moria where the Fellowship is confronted by what looks like a very small force of Orcs. The rotoscoping varies from strongly drawn to almost absent, leading to a markedly uneven treatment through the film. The characterisation, in Langford's view, similarly leaves much to be desired.[9]

Influence on Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings

[edit]The film has been cited as an influence on director Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, although Jackson said that "our film is stylistically very different and the design is different."[46] Reading about attempts to make the films live-action by Boorman and the Beatles contacting Kubrick and Lean to do the same, Jackson agreed animation was the most sensible choice at the time. Jackson remembers Bakshi's film as a "brave and ambitious attempt".[47] In another interview, Jackson stated that it had "some quaint sequences in Hobbiton, a creepy encounter with the Black Rider on the road, and a few quite good battle scenes" but "about half way through, the storytelling became very disjointed"[48] and it became "confusing"[47] and "incoherent".[49] He and his screenwriter and producer Fran Walsh remarked that Bakshi's Treebeard "looked like a talking carrot". Jackson watched the film for the first time since its premiere in 1997, when Harvey Weinstein screened it to begin the story conferences.[49]

Ahead of the films' release, Bakshi said he did not "understand it" but that he does "wish it to be a good movie". He felt bad that he wasn't contacted by Zaentz, who was involved in the project, and erroneously said they were screening his film at New Line while working on the live-action films.[49] Nevertheless, he clarified he wished the filmmakers success.[50][51] He claims Warner Brothers approached him with a proposal to make part two at the time, but he complained that they didn't involve him in the live-action film, and refused.[52]

After the films were released Bakshi said that while, "on the creative side", he does "feel good that Peter Jackson continued," he begrudged Saul Zaentz for not notifying him of the live-action films. He said that, with his own film already made, Jackson could study it: "I'm glad Peter Jackson had a movie to look at—I never did. And certainly there's a lot to learn from watching any movie, both its mistakes and when it works. So he had a little easier time than I did, and a lot better budget."[31]

Bakshi had never watched the films,[53] but saw trailers[15] and while he praised the special effects,[54][15] he said that Jackson "didn't understand" Tolkien[52] and created "special effects garbage" to sell toys,[15] saying his film has "more heart" and that, had he a similar budget, would have made a better film.[55] Bakshi was told the live-action film was derivative of his own,[56] and blamed Jackson for not acknowledging this influence: "Peter Jackson did say that the first film inspired him to go on and do the series, but that happened after I was bitching and moaning to a lot of interviewers that he said at the beginning that he never saw the movie. I thought that was kind of fucked up."[31] Bakshi then said that Jackson mentioned his influence "only once" as "PR bologny".[15] Jackson, who took a fan photograph with Bakshi in 1993, remains puzzled about Bakshi's indignation.[49] In 2015, Bakshi apologized for some of his remarks.[15] Bakshi's animator Mike Ploog praised the live-action film.[23]

In fact, Jackson did acknowledge Bakshi's film as early as 1998, when he told a worried fan that he hoped to outdo Bakshi,[57] as well as mentioning in the behind-the-scenes features that "the black Riders galloping out of Bree was an image I remember very clearly [...] from the Ralph Bakshi film."[58] In the audio commentary to The Fellowship of the Ring, Jackson says Bakshi's film introduced him to The Lord of the Rings and "inspired me to read the book" and in a 2001 interview, said he "enjoyed [the film] and wanted to know more".[59] On the audio commentary for the DVD release of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, Jackson acknowledges one shot, a low angle of a hobbit at Bilbo's birthday party shouting "Proudfeet!", as an intentional homage to Bakshi's film, which Jackson thought was "a brilliant angle".[46]

Another influence came through one of Jackson's conceptual artists, John Howe, who unwittingly copied a scene from Bakshi's film in a painting that depicted the four Hobbits hiding under a branch from a Ringwraith.[60] The painting was used in the 1987 J. R. R. Tolkien Calendar.[61] Jackson turned the painting into a scene in the film.[15][62]

Canceled sequels

[edit]The film was originally intended to be distributed as The Lord of the Rings Part I.[11][18] Initially a trilogy was planned, but this was revised to two planned films because of the limited budget.[63] Arthur Krim resigned from United Artists and was replaced by Andy Albeck. According to Bakshi, when he completed the film, United Artists executives told him that they were planning to release the film without indicating that a sequel would follow, because they felt that audiences would not pay to see half of a film.[11][18] Bakshi stated that he strongly opposed this, and agreed with the shocked viewers who complained that the film was unfinished.[11] In his view, "Had it said 'Part One,' I think everyone would have respected it."[18]

Although UA found that the film, while financially successful, "failed to overwhelm audiences", Bakshi began working on a sequel, and even had some B-roll footage shot. The Film Book of J.R.R. Tolkien's the Lord of the Rings, published by Ballantine Books on October 12, 1978, still referred to the sequel in the book's inside cover jacket.[64] Indeed, in interviews Bakshi talked about doing "a part two film picking up where this leaves off",[24] and even boasted that the second film could "pick up on sequences that we missed in the first book".[20] Zaentz went so far as to try to stop the Rankin/Bass's The Return of the King TV special (which was already storyboarded before Bakshi's film came out) from airing, so as to not clash with Bakshi's sequel.[65]

Bakshi was aware of Rankin/Bass's The Hobbit TV special, and angrily commented that "Lord of the Rings is not going to have any song for the sake of a record album."[66] During the lawsuit, he commented that "They're not going to stop us from doing The Lord of the Rings and they won't stop us from doing The Hobbit. Anyone who saw their version of The Hobbit know it has nothing to do with the quality and style of our feature. My life isn't going to be altered by what Rankin-Bass chooses to do badly."[65] Years later, he called their film "an awful, rip-off version of The Hobbit."[53]

Bakshi found the two years spent on Rings immensely stressful, and the fan reaction scathing. He took comfort in talking to Priscilla Tolkien, who said she loved it, but got into an argument with Zaentz[20] and refused to do Part Two.[16] Reports vary as to whether the argument had to do with the dropping of the "Part One" subtitle[55] or Bakshi's fee for the sequel.[33]

Bakshi said he was "proud to have made part one"[49] and that his work was "there for anyone who would make part two".[15] In interviews leading up to the year 2000, he still toyed with the idea of making the sequel.[50] For his part, Zaentz said he kept in touch with Bakshi,[20] but confided to John Boorman that making the film was the worst experience of his life, which made him protective of the property.[17] Indeed, he commented that the film "wasn't as good as we should have made"[20] and later remarked that an "animated [film] couldn't do it. It was just too complex for animated to handle it, with the emotion that was needed and the size and scope."[67]

During development of the live-action films, Bakshi said he was approached by Warner Bros. to make the second part, but refused as he was angry of not being notified about the live-action film.[52] He did use the renewed interest in his film to restore it to DVD, and had the final line redubbed to bolster the film's sense of finality. After the live-action films found success, Bakshi stated that he would never have made the film if he had known what would happen during the production. He is quoted as saying that the reason he made the film was "to save it for Tolkien, because I loved the Rings very much".[31] He concluded that the film made him realize that he was not interested in adapting another writer's story.[31]

Legacy

[edit]The film was adapted into comic book form with artwork by Spanish artist Luis Bermejo, under licence from Tolkien Enterprises. Three issues were published for the European market, starting in 1979, and were not published in the United States or translated into English due to copyright problems.[68][69]

Warner Bros. (the rights holder to the post-September 1974 Rankin/Bass library and the Saul Zaentz theatrical library) first released the film on DVD and re-released on VHS in 2001 through the Warner Bros. Family Entertainment label. While the VHS version ends with the narrator saying "Here ends the first part of the history of the War of the Ring.", the DVD version has an alternate narration: "The forces of darkness were driven forever from the face of Middle-Earth by the valiant friends of Frodo. As their gallant battle ended, so, too, ends the first great tale of The Lord of the Rings." Later, The Lord of the Rings was released in a deluxe edition on Blu-ray and DVD on April 6, 2010.[70][71] The Lord of the Rings was selected as the 36th greatest animated film by Time Out magazine,[72] and ranked as the 90th greatest animated film of all time by the Online Film Critics Society.[73]

References

[edit]- ^ "A Tom Jung Lord of the Rings key art illustration for the one sheet poster". Bonham's. 2020. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Beck, Jerry (2005). "The Lord of the Rings". The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-1-55652-591-9. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Lord of the Rings". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 31, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings (1978)". BFI. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "International Sound Track". Variety. November 21, 1979. p. 42.

- ^ Gaslin, Glenn (November 21, 2001). "Ralph Bakshi's unfairly maligned Lord of the Rings". Slate. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Maçek, J. C. III (August 2, 2012). "'American Pop'... Matters: Ron Thompson, the Illustrated Man Unsung". PopMatters. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 15, 1978). "The Lord of the Rings". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Langford, Barry (2007). "Bakshi, Ralph (1938–)". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Taylor & Francis. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Korkis, Jim (June 24, 2004). "If at first you don't succeed ... call Peter Jackson". Jim Hill Media. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Robinson, Tasha (January 31, 2003). "Interview with Ralph Bakshi". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ Spitz, Marc (November 6, 2015). "They don't make them like Ralph Bakshi anymore: "Now, animators don't have ideas. They just like to move things around"". Salon. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Robinson, Tasha (January 31, 2003). "Interview with Ralph Bakshi". The Onion A.V. Club. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2006). The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion & Guide. Houghton Mifflin. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-618-39102-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Broadway, Cliff Q. (April 20, 2015). "The Bakshi Interview: Uncloaking a Legacy". The One Ring. Archived from the original on January 18, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Weiner, David (November 10, 2018). "How the Battle for 'Lord of the Rings' Nearly Broke a Director". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Konow, David (July 16, 2014). "Alternative Universe Movies: John Boorman's Lord of the Rings". Tested.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Riley, Patrick (July 7, 2000). "'70s Version of Lord of the Rings 'Devastated' Director Bakshi". Fox News. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c Bakshi, Ralph (2010). Forging Through the Darkness: The Ralph Bakshi Vision for 'The Lord of the Rings' (bonus material). The Lord of the Rings: 1978 Animated Movie (DVD) (Deluxe Remastered ed.). Warner Video. ISBN 1-4198-8559-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Plesset, Ross (February 2002). "The Lord of the Rings: The Animated Films". Cinefantastique. Vol. 34. pp. 52–53 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d Rateliff, John D. (2011). "Two Kinds of Absence: Elision and Exclusion in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings". In Bogstad, Janice M.; Kaveny, Philip E. (eds.). Picturing Tolkien. McFarland. pp. 54–70. ISBN 978-0-7864-8473-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Croft, Janet Brennan (April 2004). "Three Rings for Hollywood: Scripts for The Lord of the Rings by Zimmerman, Boorman, and Beagle". University of Oklahoma. Archived from the original on September 3, 2006. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Ash, Roger (2008). Modern Masters Volume 19: Mike Ploog. TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 41.

- ^ a b c Naha, Ed (June 1992). "The Lord of the Rings: Bakshi in the Land of Hollywood Hobbits". Starlog. 19.

- ^ Daniels, Anthony. "Anthony Daniels interview". Anthony Daniels. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Gibson, Jon M.; McDonnell, Chris (2008). "The Lord of the Rings". Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi. Universe Publishing. pp. 148, 150, 154–155. ISBN 978-0-7893-1684-4.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings – deleted scenes". The Official Ralph Bakshi website. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings – gallery image". The Official Ralph Bakshi website. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings – gallery image". The Official Ralph Bakshi website. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Gallagher, John A. (1983). "The Directors Series: Interview with Ralph Bakshi (Part One)". directorsseries.net. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Interview with Ralph Bakshi". IGN Filmforce. May 25, 2004. Archived from the original on February 18, 2006. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ "Michael Ploog". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2015. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Lord of the Rings (1978)". AFI Catalog. Archived from the original on August 23, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Segundo, Bat (May 21, 2008). "The Bat Segundo Show #214: Interview with Ralph Bakshi". Edward Champion's Reluctant Habits. Archived from the original on December 10, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ^ Mathijs, Ernest (2006). Lord of the Rings: Popular Culture in Global Context. Wallflower Press. ISBN 1-904764-82-7.

- ^ Planer, Lindsay. The Lord of the Rings at AllMusic. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "RPM Top 100 Albums – February 24, 1979" (PDF). Library and Archives Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Sacks, Terence J. (2000). Opportunities in Animation and Cartooning Careers. McGraw-Hill. p. 37. ISBN 0-658-00183-3.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings (1978)". AFI Catalog. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "1979 Hugo Awards". The Hugo Awards. July 26, 2007. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. September 11, 2001. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1978). "Review of The Lord of the Rings". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 15, 1978). "Review of The Lord of the Rings". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ Denby, David (December 4, 1978). "Hobbit hobbled and rabbit ran". New York. 11 (49): 153–154. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (2003). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-19-516729-0. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Jackson, Peter (2001). The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, Director's Commentary. New Line Cinema.

- ^ a b Peter Jackson, as quoted at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood, on February 6, 2004. Conlan Press. Audio Archived October 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine; Retrieved on August 22, 2007.

- ^ Sibley, Brian (2006). Peter Jackson: A Film-Maker's Journey. HarperCollins. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-00-717558-1.

- ^ a b c d e Nathan, Ian (2018). Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-earth. London: HarperCollins. p. 40.

- ^ a b "'70s Version of Lord of the Rings 'Devastated' Director Bakshi". Deutsche Tolkien Gesellschaft. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Pryor, Ian (2004). Peter Jackson: From Prince of Splatter to Lord of the Rings. Thomas Dunne Books. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-312-32294-6.

- ^ a b c Simmons, Stephanie; Simmons, Areya. "Ralph Bakshi on the recent DVD release of "Wizards"". Fulvuedrive-in.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Legends of Film: Ralph Bakshi". Nashville Public Library. April 29, 2013. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Gilsdorf, Ethan (2006). "A 2006 Interview with Ralph Bakshi". Ethan Gilsdorf. Archived from the original on January 19, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Interview: Ralph Bakshi". FPS Magazine. Archived from the original on July 14, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "An Interview with Ralph Bakshi". IGN. May 26, 2004. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Ain't it cool news. "20 Questions with Peter Jackson". Herr-der-ringe-film.de. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring Appendices: From Book to Script (DVD). New Line Cinema. 2002.

- ^ "Peter Jackson interview". Explorations (October–November 2001). Barnes & Noble. October 2001.

- ^ "John Howe, Illustrator: The Black Rider". John Howe. February 24, 2012. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R.; Lee, Alan; Garland, Roger; Nasmith, Ted; Howe, John (1986). 1987 J. R. R. Tolkien Calendar. Ballantine Books.

- ^ Catalim, Esmeralda da Conceição Cunha (2009). The Trilogy of 'The Lord of the Rings': From Book to Film (PDF). University of Aveiro (master's thesis). p. 48. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

Jackson's films also owe a debt to the imagery of Ralph Bakshi and Saul Zaentz's 1978 cartoon film. The cartoon images of the hobbits hiding under tree roots, the Ringwraiths' raid on the prancing pony, and the arrowhead pursuit of Frodo in the 'Flight to the Ford' are all translated into live action.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (2006). Who's who in Animated Cartoons: An International Guide to Film & Television's Award-winning and Legendary Animators. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-55783-671-7. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Bakshi, Ralph; Zaentz, Saul (October 1978) [1978]. The Film Book of J.R.R. Tolkien's the Lord of the Rings. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-28139-X.

- ^ a b Korkis, Jim (November 15, 2013). "Animation Anecdotes #136". Cartoon Research. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Culhane, John (November 27, 1977). "Will the Video Version of Tolkien Be Hobbit Forming?". The New York Times. p. D33. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Saul Zaentz Talks Tolkien on Stage, on Film, and on Owning Lord of the Rings Rights". The One Ring. February 21, 2006. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "J.R.R. Tolkien comics". J.R.R. Tolkien miscellanea. Tolkien Library. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Warren, James; Ackerman, Forrest J.; DuRay, W. B. (June 1979). "The Lord of the Rings: The Official Authorized Magazine of J. R. R. Tolkien's Classic Fantasy Epic with 120 Full Color Illustrations from the Exciting Motion Picture!" (PDF). Warren (special edition). pp. 1–52. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ The Lord of the Rings Blu-ray (Original Animated Classic), retrieved June 7, 2022

- ^ "Ralph Bakshi's Lord of The Rings- BluRay & DVD Release Slated for April 6, 2010 Release". Bakshi Productions. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- ^ Adams, Derek; Calhoun, Dave; Davies, Adam Lee; Fairclough, Paul; Huddleston, Tom; Jenkins, David; Ward, Ossian (2009). "Time Out's 50 greatest animated films, with added commentary by Terry Gilliam". Time Out. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ "Top 100 Animated Features of All Time". Online Film Critics Society. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

External links

[edit]- 1978 films

- 1978 animated films

- 1978 children's films

- 1970s fantasy adventure films

- 1978 drama films

- American epic films

- American films with live action and animation

- American adventure drama films

- American animated fantasy films

- United Artists animated films

- 1970s English-language films

- Films scored by Leonard Rosenman

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on fantasy novels

- Films directed by Ralph Bakshi

- United Artists films

- Animated films based on British novels

- Rotoscoped films

- 1970s American animated films

- Films produced by Saul Zaentz

- Films based on multiple works of a series

- American fantasy adventure films

- Films based on The Lord of the Rings

- Films shot in Spain

- Films shot in California

- 1970s British films

- British adult animated films

- English-language fantasy adventure films