Jiří Kajínek

Jiří Kajínek | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 11 January 1961 Prachovice, Czechoslovakia |

| Criminal charges | Murder, attempted murder, assault, burglary, illegal holding of weapons, theft |

| Criminal penalty | Multiple penalties for multiple crimes; final sentencing - life in prison |

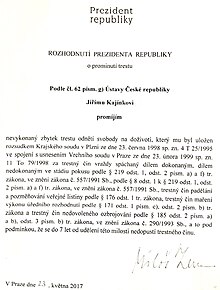

| Criminal status | Given presidential pardon |

| Spouse | Magda Gubová (married 2024–present) |

| Partner | Magda Gubová (1990–2024) |

Jiří Kajínek (Czech pronunciation: [jɪr̝iː kajiːnɛk]; born 11 January 1961) is a Czech criminal, celebrity and influencer. In 1998, he was convicted of the contracted double murder of Štefan Janda and Julián Pokoš and the attempted murder of Vojtěch Pokoš; subsequently he was given a life sentence. During his sentence, he attempted to, and was able to escape prison multiple times. In the Czech Republic, Kajínek's case has become common knowledge and public discourse has emerged debating his guilt.

On 23 May 2017, Kajínek was pardoned by president Miloš Zeman, which ended his life sentence.

Criminal activities

[edit]Early life

[edit]Kajínek was born on 11 January 1961 in Prachovice.[1] He was first imprisoned in 1982 for burglaries of summer huts.[2] However, he had run-ins with the authorities due to small theft as early as 1974, when he was 13 years old.[3]

In 1985, he was sentenced for theft from apartments, illegal holding of weapons and an assault on a public servant, as during arrest he injured two policemen using his hands and shoved another down a flight of stairs.[4]

In February 1990, he was let go, after he requested the court to cut his sentence short, which the court granted. Kajínek returned to prison later that year as he was convicted of armed robbery. During his time out of prison, he had stolen a police vehicle, while threatening two policemen with a firearm, because of this he received a sentence of 11 years in prison. The sentence given was unusually long because of evaluation given by expert witnesseses (psychologists and psychiatrists).[3]

On 18 January 1993, after being allowed to leave prison for 2 days, he did not return and remained on the run for almost two years.[5]

Life sentence for double murder

[edit]On 23 June 1998, the regional court of Plzeň gave Kajínek a life sentence. The reason given in public media was a double homicide and other less important criminal acts.[6] These acts included illegal holding of weapons, such as sub-machine guns, pistols, with and without silencers, shotguns and a large quantity of ammunition and empty magazines.[7]

According to the courts ruling, Kajínek was found guilty of killing businessman Štefan Janda and his bodyguard Julián Pokoš in Plzeň, close to the Klatovská třída and České Údolí road intersection, while they were driving a vehicle on 30 May 1993, around 8:15 pm. During this, Kajínek shot at least 12 times, also heavily wounding Vojtěch Pokoš, another bodyguard of Janda, who survived and became the cases primary witness.[8]

Another Prague businessman, Antonín Vlasák, was being extorted by Štefan Janda due to owing unresolved loans, because of this Antonín hired Kajínek for 100 000 Kč to terrify Janda. Kajínek has never publicly admitted guilt for the two murders and repeatedly tried to appeal the ruling.[9]

The case proceedings took 46 days in court and the process, due to being delayed multiple times, almost 6 years. 56 witnesses and roughly 10 expert witnesses gave testimony before court during this time. The court ruling and justification for it are 130 pages long.[5] Kajínek was to be allowed to ask for parole by 2022.[10]

Prison escapes

[edit]On 18 January 1993, the prison warden, upon recommendation from the prison committee interrupted the duration of the prison sentence between 21 and 23 January 1993. Kajínek did not return to prison however and 4 months later committed the murders for which he received the life sentence.[5]

In July 1994, when Kajínek was being placed into the České Budějovice prison he escaped using the prisons rooftops. He was caught the same day after a guard of the prison chased him, though the exact chain of events that took place remains disputed.[11][12]

On the 11 September 1996, Jiří Kajínek tried to escape Valdice prison, where he was placed after his last escape. After a 20-minute search, he was found hiding on the roof of a single-story building.

After his final sentencing, Kajínek was placed into the Mírov maximum security prison. On 29 October 2000, around 6:15 pm Kajínek managed to escape.[13] During the prison escape, Martin Vlasák, a murderer and Kajínek's friend, was supposed to escape as well. However, likely because of a brief electrical malfunction, he was not able to and remained in his cell.[14] It is often erroneously reported Kajínek is the only person to have ever escaped from Mírov; however, in 1976 Jiří Staněk and two other men escaped from Mírov as well.[15]

On 8 December 2000, Kajínek was caught by the Rapid Response Unit in the apartment of convicted murderer Ludvík Černý, a member of the Orlík killers.[16][17]

Doubts about guilt

[edit]The incident which incited the most widespread discussion about validity of Kajínek's guilt was his escape from Mírov Prison. In a 2017 survey conducted by Czech Television, more than half of the Czech public held the belief that Kajínek deserved a pardon.[18] A smaller part of the public holds the belief that Kajínek was a victim of a conspiracy, such as him not being the true murderer.[19][20] Courts have so far denied every attempt at retrial.

A deputy prime minister of the Miloš Zeman administration and later a president of the constitutional court, Pavel Rychetský, during an interview in 2001 said, "If the murders were not committed by Kajínek, it was probably done by one of the members of the police", while also mentioning non-standard conduct of the police.[21]

In 2014, the wife of one of the victims, Eva Havlová, released a book titled Mého manžela nezastřelil Kajínek (My husband wasn't shot by Kajínek). The book focuses on the chain of events from her and the family's perspective, primarily focusing on strange occurrences that followed immediately before and after the murder, which she states were in place to protect or hide the true murderer.[22]

Attempts to change sentencing

[edit]- June 1998 – Original ruling made by regional court of Plzeň.[23]

- February 1999 – The high court of Prague denies Kajínek's appeal.

- February 2001 – The ministry of justice, Pavel Rychetský, raises a request to review the original ruling to the supreme court, which is denied.

- October 2001 – The ministry of justice, Jaroslav Bureš, raises a constitutional complaint, which the Constitutional Court rejects.

- November 2001 – Jiří Kajínek raises a constitutional complaint as well, the constitutional court denies it again.

- January 2004 – Kajínek's new legal representatives Klára Slámová and Kolja Kubíček ask for renewed court proceedings, the regional court of Plzeň denies. This is followed by a series of complaints from legal representatives of Kajínek and denials from both the regional court of Plzeň and Prague high court.

- August 2006 – The ministry of justice, Pavel Němec, raises a request to review the original ruling to the supreme court, which is rejected.

- November 2007 – Legal representative of Kajínek, Klára Slámová, raises two constitutional complaints to the Constitutional Court, that are merged into one, which the court rejects.

- 2011 – Kajínek raises a request to review the original ruling, the regional court of Plzeň rejects[24] and the high court of Prague affirms the decision.

- September 2011 – Kajínek raises two additional constitutional complaints, both are denied.[25][26][27][28]

Presidential pardon

[edit]In April 2017, president Miloš Zeman said he was considering giving Kajínek a pardon at a public meeting with citizens in Čáslav, despite earlier in his term stating that he considers pardons an archaic hold-over,[29] and in February 2016 saying that he will not be giving Jiří Kajínek a pardon.[30]

On 10 May 2017, Kajínek and Zeman's wife, Ivana Zemanová, met in Rýnovice prison.[31] A day later, the president announced in a TV programme, Týden s prezidentem (a week with the president), that in the second half of May he is going to pardon Kajínek.[32] A part of the pardon was a condition of 7-years probation, during which period Kajínek must not do any crime, and if he does he is to return to prison.[33] On 23 May 2017, Miloš Zeman signed the pardon and Kajínek was released.[34]

Life after prison

[edit]Kajínek lives with his wife in Brno-Bystrc and because of large media attention to his court case has become a national celebrity.[35][36]

He has gained a substantial following on the internet, especially YouTube and Instagram.[37][38] He has also starred in TV shows, adverts and other media such as TV Prima's TV series Policie v akci (Police in action).[39]

Because of this, and his status, certain media outlets have started referring to him as influencer.[40]

Cultural impact

[edit]Kajínek has become ingrained in certain aspects of Czech culture, and that has been carried over in many types of media.

2000 – Marek Blahuš released the computer game Hlídej si svého Kajínka (Watch your Kajínek).[41]

2010 – The film Kajínek, was released to theaters, premiering on 5 August of the same year. Kajínek is portrayed in the movie by Russian actor Konstantin Lavronenko and was directed by Petr Jákl, which was his first experience with directing.

2014 – Nakladatelství Fragment published Kajínek's memoirs with the title Můj život bez mříží (My life without bars).[42]

2017 – The year when Kajínek was released from prison he was featured in the film series Já Kajínek (I, Kajínek). The series is mostly a documentary of Kajínek's life, told from his perspective.[43]

2020 – The literary alter ego of Jiří Kajínek, "Jiří Pájínek", has also been shortly featured in the satiric work of Radovan Lovčí Tuto se může stát jenom v Plzni, anebo v New Yorku (This can only happen in Plzeň, or New York).[44]

References

[edit]- ^ "Kajínek míří z vězení domů. Do rodných Prachovic" (in Czech). Deník.cz. 23 May 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Třeček, Čeněk; Pokorný, Jakub. "Příběh Jiřího Kajínka: od prvního zatčení až po slíbenou milost". iDNES.cz.

- ^ a b "Od vraždy po milost: Připomeňte si případ Kajínek! Časová osa". kurzy.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Kubová, Hana (6 February 2015). "Kajínek: Na Mírově mne šikanují, připadám si jako v gay klubu". Olomoucký deník (in Czech). Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b c "Kajinek". kriminalistika.eu. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Zahradnická, Eva (6 April 2017). "Zeman zvažuje milost pro Kajínka. Mám slzy v očích, reagoval odsouzenec". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Rozsudek, kterým poslal soudce Polák Jiřího Kajínka na doživotí". jirikajinek.cz. 12 September 2010.

- ^ "Kajinek". kriminalistika.eu. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Zahradnická, Eva (6 April 2017). "Zeman zvažuje milost pro Kajínka. Mám slzy v očích, reagoval odsouzenec". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Pokorný, Jakub (7 April 2017). "GLOSA: Pustit Kajínka? Milost, která má vlastně docela smysl". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Majer, Radek; Gális, Vladimír (18 May 2017). "V Budějovicích zastavil Kajínka výstřel". Českobudějovický deník (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Pelíšek, Antonín (24 May 2017). "Útěk Jiřího Kajínka z budějovické věznice zastavila až nastrčená noha". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Zahradnická, Eva (6 April 2017). "Zeman zvažuje milost pro Kajínka. Mám slzy v očích, reagoval odsouzenec". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "S Kajínkem měl z Mírova utéct i dvojnásobný vrah Martin Vlasák: Proč nakonec vycouval?". Blesk.cz (in Czech). 30 October 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Zahradnická, Eva (6 April 2017). "Zeman zvažuje milost pro Kajínka. Mám slzy v očích, reagoval odsouzenec". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Orličtí vrazi, úkryt uprchlého Kajínka, byt Čtveráka Černého" (in Czech). Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "Kajínek: Černý mi řekl všechno. Podle policie má zabiják na svědomí další vraždu". Deník.cz (in Czech). 26 July 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Kubištová, Pavla (14 May 2017). "S milostí pro Kajínka souhlasí 54 procent lidí, ukázal průzkum pro ČT". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Vraždili policisté? Jak mohl utéct z nejstřeženějšího vězení? Nejasnosti v kauze Kajínek". Aktuálně.cz (in Czech). 13 May 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Petříková, Petra (31 July 2010). "Jiří Kajínek: Policista řekl pravdu až teď". Deník.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Interview BBC". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Havlová, Eva (2014). Mého manžela nezastřelil Kajínek (in Czech). ISBN 978-80-253-2319-9.

- ^ "4T 25 95 1.pdf". infoprovsechny.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "Nový proces s Kajínkem soud opět zamítl - Novinky". www.novinky.cz (in Czech). 28 March 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Kajínek files complaint with Constitutional Court". Radio Prague International. 27 September 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "NALUS - databáze rozhodnutí Ústavního soudu". nalus.usoud.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Kajínek u Ústavního soudu neuspěl, nový proces nebude". Lidovky.cz (in Czech). 15 December 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "NALUS - databáze rozhodnutí Ústavního soudu". nalus.usoud.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Zahradnická, Eva (6 April 2017). "Zeman zvažuje milost pro Kajínka. Mám slzy v očích, reagoval odsouzenec". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Nikomu jsem ruce a nohy nelámal, popírá Kajínek Zemanova slova - Novinky". novinky.cz (in Czech). 17 February 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "První dáma se sešla s nájemným vrahem. Zemanová si podala ruku s Kajínkem". info.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Kajínek dostane milost, Zeman ji podepíše po návratu z Číny". iROZHLAS (in Czech). 11 May 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Ferebauer, Michal Hron, Václav (11 May 2017). "Prezident potvrdil, že po návratu z Číny udělí milost Jiřímu Kajínkovi". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hron, Jan Jiřička, Michal (23 May 2017). "Kajínek se po 23 letech dočkal milosti. Před věznicí rozdával autogramy". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kopecký, Jakub; Kotalík, Josef (23 May 2017). "Sobotka: Z vraha se stává celebrita. Volební kampaň Zemana, říká Kalousek". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Můj soused zabiják: lidé z Bystrce Kajínka většinou vítají, cítí se i bezpečněji". Brněnský deník.

- ^ "Instagram". instagram.com. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Jiří Kajínek Official". YouTube. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Krupka, Jaroslav (20 July 2018). "Kajínek propaguje vymahače. Dlužníka utéct nenecháme, říká omilostněný vrah". Deník.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Reklama s Kajínkem musí zmizet, rozhodla rada" (in Czech). Czech Radio. 3 March 2004. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Polách, Zdeněk (14 November 2000). "Hlídej si svého Kajínka!". iDNES.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Kajínek, Jiří; Eisler, Jan (2014). Můj život bez mříží (in Czech). Fragment. ISBN 978-80-253-2110-2.

- ^ "Já, Kajínek". serialzone.cz.

- ^ "Tuto se může stát jenom v Plzni, anebo v New Yorku". databazeknih.cz. ISBN 978-80-7568-183-6. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

External links

[edit]- List of works in the Czech national library whose author or primary topic is Kajínek

- Page of Kajínek on kriminalistika.eu